Abstract

Production of the bacteriocins enterocin A and enterocin B in Enterococcus faecium CTC492 was dependent on the presence of an extracellular peptide produced by the strain itself. This induction factor (EntF) was purified, and amino acid sequencing combined with DNA sequencing of the corresponding gene identified it as a peptide of 25 amino acids. The gene encodes a prepeptide of 41 amino acids, including a 16-amino-acid leader peptide of the double-glycine type. Environmental factors influenced the level of bacteriocin production in E. faecium CTC492. The optimal pH for bacteriocin production was 6.2. At pH 5.5, growth was slow, and very little bacteriocin was formed. The presence of NaCl or ethanol (EtOH) was also inhibitory to bacteriocin production, and at high concentrations of these solutes, no bacteriocin production was observed. The induction factor induced its own synthesis, and by dilution of the culture 106 times or more, nonproducing cultures were obtained. Bacteriocin production was induced in these cultures by addition of EntF. The response was linear, and low bacteriocin production could be induced by about 10−17 M EntF. This response was attenuated by low pH or the presence of high concentrations of NaCl or EtOH, and 300 times more EntF was needed to induce detectable bacteriocin production in the presence of 6.5% NaCl. High levels of bacteriocin production in cultures grown at low pH or in the presence of high concentrations of NaCl or EtOH were obtained by addition of sufficient amounts of EntF.

Bacteriocins are antibacterial peptides or proteins with spectra of inhibition usually confined to strains closely related to the producing strain. However, a number of bacteriocins from gram-positive bacteria have fairly broad inhibitory spectra (26), and bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are attractive as antimicrobial agents. Most of them are small, hydrophobic, and heat-stable peptides. They may be divided into two classes according to their chemical composition (27). Bacteriocins, termed the lantibiotics, are subjected to extensive posttranslational modifications which result in the formation of lanthionine and β-methyllanthionine from the unusual amino acids dehydroalanine and dehydrobutyrine. Class II bacteriocins contain no modified amino acids.

Several bacteriocin-producing LAB strains have been used as starter cultures in fermented foods, and some of them have been found to display a better performance in terms of inhibition of spoilage bacteria than corresponding strains not able to produce the bacteriocin (14, 18, 31, 37, 46, 48). Nisin, a lantibiotic, was the first bacteriocin which was used on a commercial scale in the food industry, and it is now widely accepted as a safe and natural preservative in certain foods in many countries (21, 25, 32, 45). However, in several trials with bacteriocin producers included in food systems, it has been difficult to demonstrate bacteriocin activity, possibly because of repression of bacteriocin synthesis. Detailed knowledge about the mechanisms underlying the regulation of bacteriocin production is of great importance for the optimal use of bacteriocinogenic LAB in inhibiting the growth of unwanted bacteria.

Various mechanisms for the regulation of bacteriocin production have been described. Synthesis of most of the bacteriocins (colicins) of Escherichia coli is induced by the SOS system, which is triggered by DNA-damaging agents such as mitomycin (30, 38), and this compound has also been found to induce the LAB bacteriocins caseicin 80 and helveticin J (19, 20, 41). Within the LAB, bacteriocin production has been shown to be influenced by factors such as pH (1, 7, 33, 34), temperature (9, 33), and the presence of other bacteria (6). De Vuyst et al. (12) suggested that amylovorin synthesis was enhanced by stress.

In some strains, expression of the bacteriocin genes is regulated by a two-component signal transduction pathway (23) consisting of a histidine protein kinase and a response regulator (3, 15, 16, 29, 40). In several of these cases, a third component of the pathway has been identified. In these three-component systems, a peptide secreted by the producing strain itself serves as the extracellular signal causing transcription of the genes necessary for bacteriocin production (15–17, 28, 29, 40).

In this work, we have studied the regulation of bacteriocin production in Enterococcus faecium CTC492, a strain with strong activity against the pathogenic bacterium Listeria monocytogenes (4). We show that an extracellular inducer peptide is necessary for bacteriocin production also in this strain, and by adding this inducer, a high level of bacteriocin production can be achieved under growth conditions that otherwise suppress bacteriocin production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and media.

The bacteriocin producer used in this study was E. faecium CTC492, the producer of enterocin A, previously described by Aymerich et al. (4). This strain was found to produce another bacteriocin identical to enterocin B described by Casaus et al. (8) (results not shown). The indicator organism used in the bacteriocin assays was Lactobacillus sake NCDO 2714, a strain sensitive to both enterocin A and enterocin B (8). The individual activities of the two bacteriocins were determined with Pediococcus pentosaceus FBB 63 (enterocin A) and Lactobacillus sake FVM 148 (enterocin B) as indicator strains (8). The strains were grown on MRS broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 30°C with an initial pH of 6.3. Standard cultures were prepared by inoculation of 10 ml of MRS broth with 5 μl of a frozen stock (−80°C) and then incubation at 30°C for 16 to 24 h. Nonproducing (Bac−) cultures of strain CTC492 were prepared by dilution of the standard stock 107 times in fresh medium. For production studies at constant pH, 0.1% (vol/vol) of a standard culture was inoculated into a fermentor (2,000-ml working volume; Biostat B; Braun). The fermentor was operated at 30°C, and slow agitation (50 rpm) maintained a homogeneous culture during each run. Anaerobic conditions were achieved by blowing sterile-filtered N2 gas through the growing cultures. The pH of the MRS broth was adjusted with hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide prior to sterilization, and during fermentation, pH was controlled by addition of 6 M sodium hydroxide. One hundred milliliters of a 40% (wt/vol) solution of glucose was added in a batchlike manner to the fermentation culture after the consumption of sodium hydroxide (6 M) had reached approximately 60 ml. Bacterial growth during the fermentations was monitored by measuring the optical density of the culture at 600 nm (1-cm path length, UV-visible spectrophotometer UV-160; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Culture samples were diluted in MRS medium to give a final optical density of less than 0.4, and sterile growth medium was used as a blank. M17 broth (Oxoid, Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, England) with 1% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17) was used as the growth medium in the induction studies.

Bacteriocin assays.

Sterile, cell-free culture supernatants were obtained by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 10 min) followed by incubation at 100°C for 10 min. Bacteriocin activity was quantified by the microtiter plate assay (24). Each well of the microtiter plate contained 200 μl of MRS broth, bacteriocin fractions at twofold dilutions, and the indicator organism (104 times diluted from the standard culture). The microtiter plate cultures were incubated overnight (16 to 20 h) at 30°C, after which growth inhibition of the indicator organism was measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm with an MR 700 Microplate Reader (Dynatech Labs, Inc.). In order to make the assays comparable, a bacteriocin standard containing 58,000 bacteriocin units (BU) ml−1 was included in each assay. The bacteriocin standard, which contained both enterocins A and B, was a concentrate of a culture supernatant (culture grown at pH 6.2). It was prepared by ammonium sulfate precipitation (400 g liter−1) and resuspended in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7).

Induction assays.

Twofold dilution series of EntF-containing samples were made in 5 ml of GM17 broth inoculated with E. faecium CTC492 (Bac−, 107-times-diluted standard culture). The cultures were incubated 20 to 24 h at 30°C and centrifuged. From each culture, 50 μl of sterilized supernatant was then assayed for bacteriocin activity with the microtiter plate assay described above. One induction unit (IU) ml−1 was defined as the minimum concentration of induction factor causing detectable bacteriocin production in the microtiter plate assay described above. The induction activities of culture supernatants were determined for samples sterilized by heat treatment as described for the bacteriocin assays. Induction studies in the presence of salt or ethanol (EtOH) were performed by the same procedure. NaCl was added to GM17 medium prior to sterilization, and EtOH was added aseptically after sterilization of the medium. In these experiments, the cultures were assayed for bacteriocin activity when they had reached the stationary phase (24 to 48 h).

Purification of the induction factor.

The induction factor was purified from the supernatant of a 2-liter culture of E. faecium CTC492 propagated for 19 h at a constant pH of 6.2. Proteins were precipitated with ammonium sulfate (400 g liter−1). After centrifugation (10,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min), the pellet was dissolved in 20 ml of water, heated to 100°C for 10 min, and then centrifuged (30,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min). The supernatant was adjusted to pH 2 by addition of 1 M hydrochloric acid, and the precipitate was removed by centrifugation (30,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min). The induction factor was extracted from this acidic supernatant by 2-propanol, adjusted to pH 2 with hydrochloric acid, to a final concentration of 70% (vol/vol). This active alcohol fraction was applied to a column (25 by 25 mm) of SP-Sepharose (Pharmacia-LKB, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) (buffer A). After being washed with buffer A, the induction factor was eluted with 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. The active fraction was applied to a reverse-phase Pep-RPC HR 5/5 column (Pharmacia-LKB) equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in distilled water. The induction factor was desorbed from the column with a gradient of 2-propanol against 0.1% TFA in distilled water. The pure compound was obtained by rechromatography of the active fractions.

Amino acid sequencing.

The NH2-terminal amino acid sequence of the induction factor was determined by Edman degradation with a 477A automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with an on-line 120A phenylthiohydantion amino acid analyzer, as described previously (10). Amino acid analyses were performed with the Sequence Analysis software package (version 8) (11) licensed from the Genetics Computer Group, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

PCR and DNA sequencing.

DNA was prepared by the method of Anderson and McKay (2). PCR was performed with Dynazyme (Finnzymes) in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). Restriction enzymes and other DNA-modifying enzymes were used as recommended by the manufacturer (Promega). The DNA primers used in the PCR and DNA sequencing are shown in Table 1. The PCR products were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis and extracted from the gel with the GeneClean II kit (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.). The PCR products were sequenced with the ABI Prism Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer) and an ABI PRISM 377 DNA Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR and DNA sequencing in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| IF2 | 5′ACR AAY TCN ACN ARR TT 3′a |

| IF4 | 5′TAA AGG GAG GTG CTG GAA CA 3′ |

| TH10 | 5′GAT TAT GAA ACA TTT AAA AAT TTT GTC 3′ |

| TH11 | 5′CCT AAA TAT TCT GAT ATT CTT 3′ |

| KS | 5′CGA GGT CGA CGG TAT CG 3′ |

| T7 | 5′GTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG 3′ |

R, A, or G; Y, C or T; N, A, C, G, or T.

The degenerate primer, IF2, and one primer from the enterocin A structural gene, TH10 (4), were used in PCR with E. faecium CTC492 DNA. The PCR conditions included a hot start at 97°C (4 min), followed by 30 s at 94°C, an annealing temperature of 40°C (1 min), and polymerization at 72°C (3 min). The reaction was repeated for 40 cycles. PCR was performed directly with this PCR mix with IF2 and TH11 as primers and with an annealing temperature of 45°C. The 1.6-kb PCR product formed was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis. This fragment and E. faecium CTC492 DNA were cut with restriction enzymes and ligated to restricted pBluescript SK II (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and the ligation mixtures obtained were subjected to PCR and sequencing according to the method of Casaus et al. (8) with primers specific for entF and the vector.

Synthetic induction factor.

Peptides were synthesized at the Facility for Molecular Biology at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom) and purified to >95% purity by standard reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. The molecular weights of the purified synthetic peptides were verified by laser-desorption mass spectrometry (yielding molecular weights of 2,667.2 and 2,711.2 for the wild-type and mutant peptides, respectively). Prior to being assayed, the synthetic peptides were dissolved in TFA to a final concentration of 10 mg ml−1 and then diluted as described for the induction assays.

RESULTS

pH optimum for bacteriocin production.

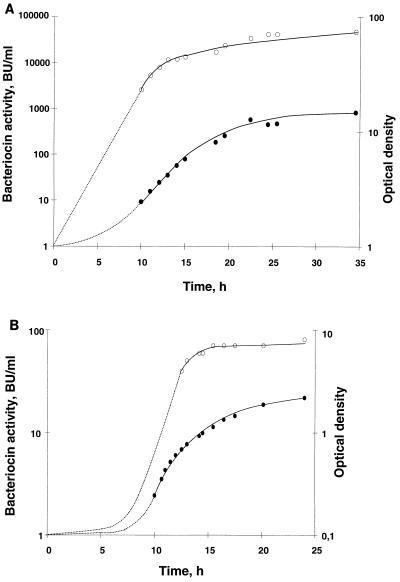

E. faecium CTC492, a bacteriocin producer with a strong antilisteria activity, was previously described by Aymerich et al. (4). This strain produces two bacteriocins, enterocin A (4) and enterocin B (unpublished results), that have been described recently (8). In batch culture, E. faecium CTC492 grew to an optical density of 3, and the final pH of the culture was 4.6. Bacteriocin production paralleled growth and reached an activity of 2,500 BU ml−1 in the stationary phase (data not shown). In order to prolong the growth phase and hence the growth-associated enterocin production, fermentations were carried out at constant pH. Under constant pH conditions, the cultures appeared to be carbon or energy limited, since the cell yield doubled when a total of 4% (wt/vol) glucose was fed to the culture (results not shown). Higher bacteriocin activities were obtained in MRS with extra glucose (4% [wt/vol]) at pH values between 5.8 and 7.0 (Table 2). Bacteriocin yield was not increased any further at higher concentrations of glucose (>4% [wt/vol]) or concentrated (4×) MRS medium (data not shown). In cultures grown at pHs of 5.5 and 8.0, less bacteriocin activity was detected than in cultures grown without the pH control (Table 2). The highest yields were obtained in the pH range between 5.8 and 6.5, with an optimum at pH 6.2 (Fig. 1A). About 20 times more bacteriocin (46,000 BU ml−1) was obtained at pH 6.2, compared to that in cultures grown without pH control and additional glucose. This pH was, however, not the optimal pH for growth of the organism. Growth was faster at higher pH values. The maximum biomass was reached after 18 h at pH 8.0, compared to 34.5 h at pH 6.2, but only about 5% of the optimal bacteriocin yield was obtained at this high pH (data not shown). Cultures of E. faecium CTC492 grown at pH ≥5.8 reached comparable levels of biomass (data not shown). When E. faecium CTC492 was grown at pH 5.5, growth was very slow and bacteriocin production was low (Fig. 1B). Only 40 BU ml−1 was produced after 12.5 h, and even though the culture reached an optical density of 2.2 within 24 h, maximum bacteriocin activity was only 80 BU ml−1.

TABLE 2.

Maximum bacteriocin and induction activities for E. faecium CTC492 cultures at different pH valuesa

| pH condition during growth | Maximum bacteriocin activity (BU ml−1 [1,000]) | Maximum induction activity (IU ml−1 [1,000])b |

|---|---|---|

| Without pH control (final pH 4.6) | 2.5 | 40 |

| 5.5 | 0.08 | —c |

| 5.8 | 25 | 83 |

| 6.0 | 25 | 320 |

| 6.2 | 46 | 640 |

| 6.5 | 26 | 83 |

| 7.0 | 10 | 83 |

| 8.0 | 2 | NDd |

Maximum bacteriocin and induction activities were detected in supernatants of E. faecium CTC492 cultures grown at different pH values in MRS broth. A total of 0.1% of the standard culture was used as an inoculum, and the operating temperature was 30°C.

One IU ml−1 equals 10−17 M induction factor.

—, induction activity was below the detection limit of the assay.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 1.

Growth and bacteriocin production of E. faecium CTC492 in MRS broth at 30°C and pH values 6.2 (A) and 5.5 (B). Cells were grown in a Biostat B fermentor with 2 liters of MRS broth and a total of 4% (wt/vol) glucose (see Materials and Methods). An inoculum of 0.1% was used. Bacteriocin activity was assayed for the cell-free culture supernatants. •, optical density at 600 nm; ○, bacteriocin activity in BU per milliliter.

Induction of bacteriocin production.

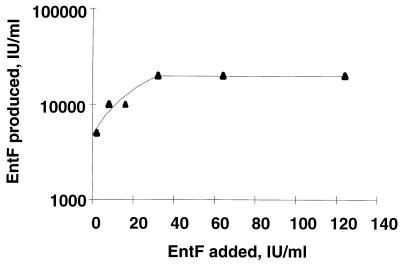

Inoculum size was of great importance for bacteriocin production in E. faecium CTC492. Spontaneous loss of bacteriocin production was observed when standard cultures were diluted 106 times or more in MRS or GM17 medium. Bacteriocin production could, however, be restored by addition of a sterile sample of a culture supernatant from a bacteriocin-producing culture (Bac+) of strain CTC492, but not from a non-bacteriocin-producing culture (Bac−). The supernatant from the bacteriocin-producing culture was capable of inducing production of both enterocin A and enterocin B (data not shown). These results indicate that the supernatant from a bacteriocin-producing culture contains an induction factor (EntF). In order to test if EntF could induce its own production, as well as the production of enterocins A and B, the following experiment was performed. Different concentrations of EntF were added to Bac− cultures of E. faecium CTC492, and the induction activities of the culture supernatants, harvested in the stationary phase, were assayed. As shown in Fig. 2, the induction factor was autoinduced.

FIG. 2.

Autoinduction of the induction factor EntF. Bac− cultures of E. faecium CTC492 were induced with different initial activities of the induction factor and then incubated at 30°C overnight in GM17 medium. The cultures were harvested, and the induction activities of the supernatants were assayed. One IU ml−1 equals 10−17 M induction factor.

Characterization of the induction factor and its gene.

The inducer present in the supernatant of a bacteriocin-producing culture, propagated at the optimal pH for production, 6.2, was purified (Table 3). Very little material was isolated, and the entire sample was subjected to amino acid sequencing. As judged by amino acid sequencing, about 3 pmol of the pure peptide with the following sequence was found: Xaa-Xaa-Thr- Lys-Pro-Gln-(Gly)-Lys-Pro-Ala-Ser-Asn-(Leu)-Val-Glu- (Phe)-Val. Xaa represents unknown amino acids, while the amino acids enclosed in parentheses were not determined with certainty.

TABLE 3.

Purification of enterocin induction factor (EntF)

| Purification step (vol [ml]) | EntF activitya

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IU ml−1 | Total IU | % Yield | |

| Culture supernatant (2,000) | 640,000 | 1.3 × 109 | 100 |

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation (25) | 42 × 106 | 1.0 × 109 | 81 |

| Acid supernatant (30) | 42 × 106 | 1.3 × 109 | 97 |

| 2-Propanol fraction (100) | 3 × 106 | 0.3 × 109 | 20 |

| SP-Sepharose eluate (30) | 3 × 106 | 90 × 106 | 6 |

| Reverse-phase chromatography (1) | 3 × 106 | 3 × 106 | 0.2 |

One IU ml−1 equals 10−17 M induction factor.

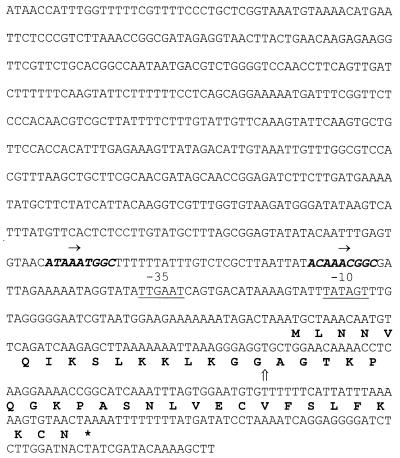

Based on the induction factor’s amino acid sequence, degenerate DNA primers were constructed in order to characterize the induction factor’s structural gene, entF, by PCR. Use of primers specific for entF and the enterocin A operon revealed that entA and entF are transcribed in the same direction and separated by about 1.6 kb (4). The DNA sequence of the entF-containing region is shown in Fig. 3. Only one open reading frame was found in the sequence shown. With the exception of position 16 (Cys in DNA sequencing, Phe in amino acid sequencing), the DNA sequence confirmed the results obtained from the amino acid sequencing. The mature induction factor was chemically synthesized. In order to resolve the discrepancy between the sequences obtained by sequencing of DNA and the purified peptide, 25-mers with either F or C at position 16 were made. The two peptides showed a remarkable difference in biological activity. The Cys-16 peptide could induce bacteriocin production at 10−17 M, whereas at least 100,000 times more (10−12 M) of the Phe-16 variant was needed for induction (data not shown). These results confirm the DNA sequence, which also revealed that the induction factor is translated as a 41-amino-acid prepeptide. This prepeptide contains a 16-amino-acid N-terminal leader sequence with all the consensus elements of a leader peptide of the double-glycine type (22). The sequence data revealed that the induction factor is a cationic, hydrophobic peptide of 25 amino acids with an estimated isoelectric point of 9.88. The calculated molecular mass of the induction factor was 2,667 Da. Heat treatment at 100°C for 10 min did not reduce the induction factor activity, indicating that EntF is a thermostable peptide (results not shown). Both enterocin A and enterocin B were induced by synthetic EntF (data not shown). The synthetic peptide was also assayed for bacteriocin activity against L. sake NCDO 2714. No growth inhibition was detected at a concentration of 50 μg ml−1. The enterocin induction factor shared 45.8 and 30.4% sequence identity with the carnobacteriocin B2 and BM1 induction factor (40, 43) and the putative inducer of sakacin A (3, 16), respectively. As shown in Fig. 4, the main differences between these peptides are found in their N-terminal parts, while the C-terminal parts appear to be conserved among them. The enterocin induction factor did not show any significant sequence similarity to any bacteriocin.

FIG. 3.

Nucleotide sequence of the region encoding the enterocin induction factor of E. faecium CTC492 (entF) and the deduced amino acid sequence. The vertical arrow indicates the processing site of the peptide. The stop codon is indicated with an asterisk, and possible promoter −35 and −10 sites are underlined. Direct repeats are given in boldface italic and are indicated by horizontal arrows.

FIG. 4.

Sequence comparison of the enterocin induction factor (EntF) with the inducer of carnobacteriocin B2 (CbnS) (39, 40) and the putative inducer of sakacin A (open reading frame 4 [ORF4]) (3, 16).

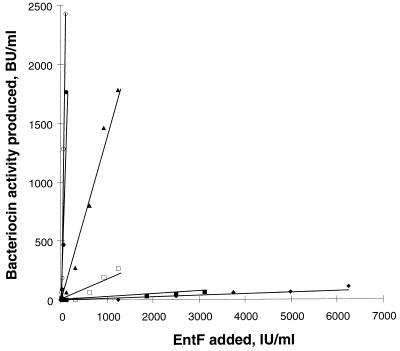

Level of induction is dose dependent and is affected by environmental factors.

By using the induction assay (see Materials and Methods for details), we found that induced bacteriocin production showed a linear dose-response relationship to added induction activities up to a level of 125 IU ml−1 (Fig. 5). At higher induction activities, a bacteriocin production saturation level was reached at 2,500 BU ml−1 (data not shown). This saturation level corresponds to maximum bacteriocin production in a standard culture. These results were obtained both with culture supernatants and with synthetic peptide. Table 2 shows the maximum induction activities (detected in the stationary growth phase) of cultures grown at different pH values. The highest bacteriocin production was observed in cultures with the highest induction activities.

FIG. 5.

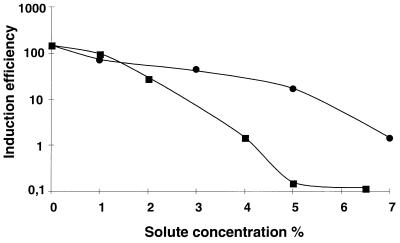

Induction of bacteriocin production in Bac− cultures of E. faecium CTC492. One IU ml−1 equals 10−17 M induction factor. The growth media used were GM17 medium alone and GM17 medium with different concentrations of sodium chloride. The induction factor (EntF) was added to Bac− cultures at the time of inoculation and incubated at 30°C for 24 to 48 h until they reached the stationary phase. The bacteriocin activity was determined in the supernatants of the cultures by the microtiter plate assay. ○, control culture (GM17 medium only); •, 1.0% NaCl; ▴, 3.0% NaCl; □, 4.0% NaCl; ▪, 5.0% NaCl; ⧫, 6.5% NaCl.

When E. faecium CTC492 was grown at pH 5.5, growth was slow and bacteriocin production was very low (a maximum of 80 BU ml−1). We hypothesized that the low bacteriocin production could be due to insufficient amounts of induction factor in the inoculum. To test for this, the induction factor was added to cultures grown at pH 5.5. An over-200-fold increase in bacteriocin production (18,500 BU ml−1) was obtained by addition of 200 IU ml−1 to the cultures at the time of inoculation, showing that the level of induction factor was limiting for bacteriocin production at pH 5.5. We further investigated bacteriocin production under other unfavorable growth conditions. Like low pH, high concentrations of salt or EtOH adversely affected growth and bacteriocin production. In the presence of 6.5% NaCl or 7% ethanol, no bacteriocin production could be detected. However, as shown in Table 4, considerable bacteriocin production could be obtained under these growth conditions as well by supplementing the cultures with induction factor. The effects of NaCl and EtOH on the response to the induction factor were studied with the bacteriocin induction assay. Linear dose-response relationships between EntF added and bacteriocin production were seen under all growth conditions tested (see Fig. 5 for the effect of NaCl). However, the response to the induction factor was attenuated by the solutes in a concentration-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 5 and 6, the slopes of the dose-response curves, a measurement of the cultures’ induction efficiencies, decreased with increasing concentrations of salt or EtOH, and the response was reduced even at concentrations that had no apparent effect on growth of the organism. Thus, higher concentrations of inducer were needed to sustain bacteriocin production in the presence of the solutes. The concentration of inducer needed to obtain detectable bacteriocin production in the presence of 6.5% NaCl or 7% EtOH was about 300 times higher than that without these additives.

TABLE 4.

Maximum bacteriocin activities for E. faecium CTC492 cultures with different concentrations of NaCl and EtOHa

| Solute concn | Maximum bacteriocin activity (BU ml−1) | Maximum induced bacteriocin activity (BU ml−1) |

|---|---|---|

| None (GM17 broth only) | 2,500 | 2,500 |

| NaCl | ||

| 3.0% | 2,500 | 2,500 |

| 5.0% | 1,250 | 1,250 |

| 6.5% | —b | 900 |

| EtOH | ||

| 5.0% | 2,500 | 2,500 |

| 6.0% | 1,250 | 1,250 |

| 7.0% | — | 1,250 |

Results represent maximum bacteriocin activities detected in culture supernatants of E. faecium CTC492 cultures (0.1% inoculum) and maximum induced bacteriocin activities in supernatants of E. faecium CTC492 cultures (Bac−) grown in MRS broth with different concentrations of NaCl and EtOH.

—, Bacteriocin activity was below the detection limit of the microtiter plate assay.

FIG. 6.

Induction efficiencies in cultures of E. faecium CTC492 grown in GM17 medium with different concentrations of solutes. The induction efficiency of a culture was defined as the slope of the line correlating induced bacteriocin production and added induction activity. Induction efficiency is shown as a function of increasing concentrations of sodium chloride (▪) and EtOH (•).

DISCUSSION

One aim of the present study was to optimize bacteriocin production in E. faecium CTC492. We have shown that bacteriocin production in this strain follows primary metabolite kinetics, and thus by keeping the pH constant and adding extra glucose, biomass yield, and hence bacteriocin production, was increased.

Bacteriocin production was found to be a regulated process. In LAB, pH and temperature have been found to influence bacteriocin production (1, 7, 13, 33, 34), and De Vuyst et al. (12) suggested that amylovorin synthesis was enhanced by stress. However, the mechanisms by which bacteriocin production is regulated by environmental factors have not been studied. In many systems, it has been shown that bacteriocin production is induced by external inducers: in Lactobacillus acidophilus, the producer of lactacin B (5), the signal is a cell-associated protein compound from other gram-positive bacteria. A dose-dependent induction of bacteriocin production was observed by Barefoot et al. (6). Mitomycin induces production of caseicin 80 and helveticin J (19, 20, 41). In other bacteria, the inducer is a component secreted by the producing strain itself (15, 17, 28, 29, 35, 40). In some of these systems, the transcription of the bacteriocin genes has been shown to be regulated by a three-component signal transduction pathway involving an induction factor, a histidine protein kinase, and a response regulator (3, 15, 17, 28, 29, 35, 40). The induction factor is believed to bind to the histidine protein kinase and to activate it to phosphorylate the response regulator, which then stimulates transcription of the target genes.

The enterocin induction factor described here has several features in common with the inducers of the nonlantibiotic bacteriocins sakacin P and carnobacteriocin B2 and BM1, as well as the bacteriocins formed by Lactobacillus plantarum C11 (16, 17, 40). They are all small, heat-stable, cationic, and hydrophobic peptides that are autoinduced and synthesized as prepeptides with leader sequences of the double-glycine type (35). Furthermore, the enterocin induction factor showed significant sequence similarity to the peptide inducing carnobacteriocin B2 and BM1 synthesis in C. piscicola LV17B, and to the possible inducer of sakacin A (3, 16). A C-terminal sequence of nine amino acids is particularly well conserved in these three peptides (Fig. 4). Two cysteine residues, probably joined by a disulfide bridge, flank this sequence. An exchange of one of them (Cys-16) with Phe in EntF caused a 100,000-fold drop in induction activity, demonstrating the importance of this part of the peptide for biological activity.

Like E. faecium CTC492, C. piscicola LV17B produces more than one bacteriocin that can be induced by extracellular induction factor(s). The bacteriocins of C. piscicola LV17 are homologous to either enterocin A or B (39, 47). We have shown that both enterocin A and enterocin B are induced by the same peptide. Whether CbnS can induce synthesis of carnobacteriocin A in addition to carnobacteriocin B2 and BM1 in C. piscicola LV17 remains to be shown.

The similarities between the induction system in E. faecium CTC492 and those of other bacteriocin producers suggest that production of enterocins A and B is also regulated by a three-component signal transduction pathway (3, 15, 17, 29, 40). There are, however, important differences between the enterocin system and the other systems that have been studied. We have been able to demonstrate induction of bacteriocin production down to 10−17 M synthetic inducer, while threshold levels of about 10−10 M have been reported for the plantaricin A, sakacin P, nisin, and carnobacteriocin B2 and BM1 systems (16, 17, 29, 40). Furthermore, these induction factors are synthesized at the same or similar amounts as the bacteriocin(s) they induce (17, 36, 39, 44). E. faecium CTC492 produced much less induction factor. From the specific activity of the induction factor (1020 IU mol−1), it was calculated that E. faecium CTC492 produced at most 6 · 10−12 M (16 ng liter−1) induction factor, which corresponds to only about 0.01% of the bacteriocin produced (at pH 6.2 [data not shown]). Such low concentrations of inducer would be insufficient to sustain bacteriocin production in other inducible systems studied (16, 17, 29, 40). The higher sensitivity of this system appears to be balanced by a lower level of EntF production.

As noted by Diep et al. (16), repeated DNA sequences of 9 nucleotides, separated by an AT-rich stretch of 12 to 13 nucleotides, are found upstream of the initiation region of transcription for both bacteriocin and inducer genes in L. plantarum C11, L. sake Lb706, and C. piscicola LV17. This specific spacing of the repeats directs them to the same side of the DNA double helix. It is believed that the active phosphorylated response regulator can bind specifically to these repeated sequences and activate transcription (16). The comparable levels of both induction factor and bacteriocins in the plantaricin and sakacin P systems probably reflect the fact that the repeats upstream of the induction factor and the corresponding bacteriocin gene(s) show a high degree of identity (16). Two 12-bp repeats separated by 13 nucleotides upstream of the putative promoter of entA (4) may serve the same function in controlling bacteriocin production as the repeats in the systems mentioned above. However, similar sequences were not found in the vicinity of the entF gene. Instead a repeat of 9 nucleotides spaced by 25 nucleotides (80% AT) was found just upstream of the putative −35 region of the EntF promoter. This spacing directs the repeats to the same side of the DNA helix, and the repeats probably function as a binding site for the putative phosphorylated response regulator. It is noteworthy that the spacing between the repeats is larger in this system than in the systems mentioned above, which are all separated by 12 to 13 nucleotides and which are all involved in much higher levels of protein production. The differences in the upstream regions of entA and entF may allow differentiated gene expression from the two promoters, although they are both induced by the same signal peptide.

The enterocin induction factor induces its own synthesis, and yet we were able to demonstrate a dose-dependent induction of bacteriocin production. This apparent paradox can be explained if the cells become less inducible late in the growth phase. In the induction experiments described here, this was indeed true. During growth, the pH of the medium was lowered, and our results show that at low pH, the induction is inhibited.

We have shown that the response to the induction factor is also influenced by other environmental factors. In addition to pH, the presence of EtOH or salt was found to attenuate the response. These effects are probably not unique to this strain. Ahn and Stiles (1) found that production of bacteriocin did not occur at low pH in C. piscicola LV17.

Induction of bacteriocin production in E. faecium CTC492 could be demonstrated at as little as 10−17 M induction factor, indicating a high affinity for its receptor (the putative kinase). It is possible that low pH or the presence of EtOH or NaCl negatively influences the binding of the induction factor to its receptor. Simple dilution of the cells is sufficient to turn induction off. Thus, the signal elicited by the binding of the induction factor to its receptor must be short-lived. This has been shown to be the case in two-component regulatory systems (23, 42). The response is modulated by the opposed reactions, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, of the response regulator. This balance may be affected by environmental factors such as pH and high concentrations of EtOH or salt (23, 42).

Our findings are of importance for the application of bacteriocin-producing strains. We have shown that the range of growth conditions at which bacteriocin production takes place can be expanded by the addition of the induction factor, thereby increasing the potential of bacteriocin producers as microbial antagonists.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Sletten for performing the amino acid sequencing analysis and J. Gray for making the synthetic peptides.

T. Nilsen was funded by The Nordic Industrial Fund, grant P93154. H. Holo was supported by grants from The Norwegian Dairies Association, Oslo, Norway.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn C, Stiles M E. Plasmid-associated bacteriocin production by a strain of Carnobacterium piscicola from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2503–2510. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2503-2510.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson D G, McKay L L. Simple and rapid method for isolating large plasmid DNA from lactic streptococci. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:549–552. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.3.549-552.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Axelsson L, Holck A. The genes involved in production of and immunity to sakacin A, a bacteriocin from Lactobacillus sake Lb706. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2125–2137. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2125-2137.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aymerich T, Holo H, Håvarstein L S, Hugas M, Garriga M, Nes I F. Biochemical and genetic characterization of enterocin A from Enterococcus faecium, a new antilisterial bacteriocin in the pediocin family of bacteriocins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1676–1682. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1676-1682.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barefoot S F, Klaenhammer T R. Purification and characterization of the Lactobacillus acidophilus bacteriocin lactacin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;26:328–334. doi: 10.1128/aac.26.3.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barefoot S F, Chen Y-R, Hughes T A, Bodine A B, Shearer M Y, Hughes M D. Identification and purification of a protein that induces the production of the Lactobacillus acidophilus bacteriocin lactacin B. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3522–3528. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.10.3522-3528.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biswas S R, Ray P, Johnson M C, Ray B. Influence of growth conditions on the production of a bacteriocin, pediocin AcH, by Pediococcus acidilactici AcH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1265–1267. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1265-1267.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casaus P, Nilsen T, Cintas L M, Nes I F, Hernándes P E, Holo H. Enterocin B, a new bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium T136 which can act synergistically with enterocin A. Microbiology. 1997;143:2287–2294. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-7-2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cintas L M, Rodriguez J M, Fernandez M F, Sletten K, Nes I F, Hernandez P E, Holo H. Isolation and characterization of pediocin L50, a new bacteriocin from Pediococcus acidilactici with a broad inhibitory spectrum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2643–2648. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2643-2648.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornwell G G, Sletten K, Johansson B, Westermark P. Evidence that the amyloid fibril protein in senile systemic amyloidosis is derived from normal prealbumin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;154:648–653. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devereux J P, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vuyst L, Callewaert R, Crabbé K. Primary metabolite kinetics of bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus amylovorus and evidence for stimulation of bacteriocin production under unfavourable growth conditions. Microbiology. 1996;142:817–827. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-4-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Vuyst L, Callewaert R, Pot B. Characterization of the antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus amylovorus DCE 471 and large scale isolation of its bacteriocin amylovorin L471. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Vuyst L, Vandamme E J. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: microbiology, genetics and applications. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic & Professional; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Nes I F. A bacteriocin-like peptide induces bacteriocin synthesis in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:631–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Nes I F. Characterization of the locus responsible for the bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus plantarum C11. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4472–4483. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4472-4483.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eijsink V G H, Brurberg M B, Middelhoven P H, Nes I F. Induction of bacteriocin production in Lactobacillus sake by a secreted peptide. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2232–2237. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2232-2237.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foegeding P M, Thomas A B, Pilkington D H, Klaenhammer T R. Enhanced control of Listeria monocytogenes by in situ-produced pediocin during dry fermented sausage production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:884–890. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.3.884-890.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fremaux C, Klaenhammer T R. An inducible promoter controls the expression of helveticin J, a large heat-labile bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus helveticus. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:P121. . (Abstract G10.) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fremaux C, Ahn C, Klaenhammer T R. Molecular analysis of the lactacin F operon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3906–3915. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3906-3915.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross E, Morell J L. The structure of nisin. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:4634–4635. doi: 10.1021/ja00747a073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Håvarstein L S, Holo H, Nes I F. The leader peptide of colicin V shares consensus sequences with leader peptides that are common among peptide bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. Microbiology. 1994;140:2383–2389. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Two-component signal transduction. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holo H, Nilssen Ø, Nes I F. Lactococcin A, a new bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris: isolation and characterization of the protein and its gene. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3879–3887. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3879-3887.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurst A. Nisin. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1981;27:85–123. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack R W, Tagg J R, Ray B. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:171–200. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klaenhammer T R. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:39–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleerebezem M, Quadri L E N, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M. Quorum sensing by peptide pheromones and two-component signal transduction systems in Gram positive bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:895–904. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4251782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuipers O P, Beerthuyzen M M, Pascalle G, de Ruyter G A, Luesink E J, de Vos W M. Autoregulation of nisin biosynthesis in Lactococcus lactis by signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazdunski C J, Baty D, Geli V, Cavard D, Morlon J, Lloubes R, Howard S P, Knibiehler M, Chartier M, Varenne S, Frenette M, Dasseux J L, Pattus F. The membrane channel-forming colicin A: synthesis, secretion, structure, action and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;947:445–464. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(88)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leisner J J, Gordon Greer G, Stiles M E. Control of beef spoilage by a sulfide-producing Lactobacillus sake strain with bacteriocinogenic Leuconostoc gelidum UAL187 during anaerobic storage at 2°C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2610–2614. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2610-2614.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattick A T R, Hirsch A. A powerful inhibitory substance produced by a group N streptococci. Nature. 1944;154:551–552. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mørtvedt-Abildgaard C I, Nissen-Meyer J, Jelle B, Grenov B, Skaugen M, Nes I F. Production and pH-dependent bactericidal activity of lactocin S, a lantibiotic from Lactobacillus sake L45. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:175–179. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.175-179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muriana P M, Klaenhammer T R. Conjugal transfer of plasmid determinants for bacteriocin production and immunity in Lactobacillus acidophilus 88. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:553–560. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.553-560.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nes I F, Diep D B, Håvarstein L S, Brurberg M B, Eijsink V G H, Holo H. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:113–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00395929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nissen-Meyer J, Larsen A G, Sletten K, Daeschel M, Nes I F. Purification and characterization of plantaricin A, a Lactobacillus plantarum bacteriocin whose activity depends on the action of two peptides. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1973–1978. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pucci M J, Vedamuthu E R, Kunka B S, Vandenburgh P A. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by using bacteriocin PA-1 produced by Pediococcus acidilactici PAC 1.0. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2349–2353. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.10.2349-2353.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pugsley A P. The ins and outs of colicins. I. Production and translocation across membranes. Microbiol Sci. 1984;1:168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quadri L E N, Sailers M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Chemical and genetic characterization of bacteriocins produced by Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12204–12211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quadri L E N, Kleerebezem M, Kuipers O P, De Vos W M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Characterization of a locus from Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B involved in bacteriocin production and immunity: evidence for global inducer-mediated transcriptional regulation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6163–6171. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6163-6171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rammelsberg M, Muller E, Radler F. Caseicin 80: purification and characterization of a new bacteriocin from Lactobacillus casei. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:1901–1906. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russo F D, Silhavy T J. The essential tension: opposed reactions in bacterial two-component regulatory systems. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:306–309. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90007-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saucier L, Poon A, Stiles M E. Induction of bacteriocin in Carnobacterium piscicola LV17. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;78:684–690. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tichaczek P S, Nissen-Meyer J, Nes I F, Vogel R F, Hammes W P. Characterization of the bacteriocins curvacin A from Lactobacillus curvatus LTH1174 and sakacin P from L. sake LTH673. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:460–486. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vandenbergh P A. Lactic acid bacteria, their metabolic products and interference with microbial growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Winkowski K, Crandall A D, Montville T J. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes by Lactobacillus bavaricus MN in beef systems at refrigeration temperatures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2552–2557. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2552-2557.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Worobo R W, Henkel T, Sailer M, Roy K L, Venderas J C, Stiles M E. Characteristics and genetic determinant of a hydrophobic peptide bacteriocin, carnobacteriocin A, produced by Carnobacterium piscicola LV17A. Microbiology. 1994;140:517–526. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yousef A E, Luchansky J B, Degnan A J, Doyle M P. Behavior of Listeria monocytogenes in wiener exudates in the presence of Pediococcus acidilactici H or pediocin AcH during storage at 4 or 25°C. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1461–1467. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1461-1467.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]