Abstract

When conscious, about 50% to 60% of hospice patients report a “visitation” by someone who is not there while they dream or are awake: a phenomenon known as End-of-Life Dreams and Visions (ELDVs). Since the dying process is frequently complicated by delirium, ELDVs risk being misidentified as such by professionals and caregivers. To observe these phenomena from patients’ perspectives, we conducted a systematic review to aggregate and synthesize the findings from the qualitative studies about ELDVs of patients assisted in hospices to indicate future directions for research and care. MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were searched, yielding 293 documents after duplicates were removed. Six qualitative articles reporting on five unique studies conducted in hospice settings were included in the meta-synthesis. We generated three main categories: i) typologies of ELDVs reported, ii) emotional consequences, and iii) intersubjective meaning-making. The ELDVs reported were experiences that remained intimate and unsocialized and thus preventing participants from defining a shared sense in their relationships. Training healthcare professionals to recognize ELDVs and take advantage of them in the care relationship is desirable. We also encourage the patient’s family members to listen and understand ELDVs when they occur actively. For caregivers to know how to interpret these phenomena may provide them with additional strategies for supporting, reassuring, and strengthening their relationships with their loved ones. The review allowed us to inform healthcare professionals and caregivers about how to help patients share their emotional and identity-related experiences and meaning-making in end-of-life.

Keywords: deathbed visions, hospice, cancer patients, end-of-life dreams, systematic review, meta-synthesis

Introduction

When conscious, about 50% to 60% of hospice patients 1 report a “visitation” by someone who is not there while they dream or are awake: a phenomenon renowned in end-of-life care as a deathbed vision 2 or End-of-Life Dreams and Visions (ELDVs). 3 Visions, also commonly defined as idiosyncratic perceptions 4 or pseudo-hallucinations, 5 entail objects/content/events/situations perceived as real but with no tangible stimuli. These experiences can be visual, auditory, and/or kinesthetic. Besides, many studies describe how vivid dreams are prevalent during dying.5,6

ELDVs differ from hallucinations due to delirium. Even if also delirium can be very common in patients with palliative care needs,1,7 hallucinations are more stressful. They include disorganized thinking and disorientation, 7 involving a breakdown in attention and awareness. 7 On the contrary, ELDVs and their contents are generally comforting and not accompanied by disorganized thinking1,7,8 as in the Near-Death Experiences 9 (NDEs), where the acronym NDE is used in this article in the precise sense of “authentic NDE”, namely “Recalled Experience of Death” (RED), or “classical NDE”, as well substantiated in a recent consensus statement by Parnia and colleagues. 10

ELDVs are something different from NDEs, 11 which are probably better known. NDEs are typically described in cases of severe physical impairment (immediate life-threatening situation, such as cardiac arrest) or the clear perception of an immediate risk of death, 9 and usually recalled by individuals because resuscitated back to life. 12 ELDVs instead occur in the absence of acute conditions. 11 Moreover, this observation justifies specific attention towards ELDVs in comparison to NDEs since, for the formers, it obviously cannot be invoked the same physiological (hypercapnia, cerebral hypoxia, etc.) or psychological (defense and reaction mechanism towards a sudden and unexpected shock, etc.) dynamics to which reference is made when trying to explain NDEs. But not only in general terms, since in the hospice setting (intended as facilities or programs), specific attention to ELDVs different from that to NDEs is also justified: in fact, although the individuals in hospice care may feel close to death and, in any case, this situation is objective, if they experience visions of NDEs, however, these cannot be cataloged as such unless they are really in an immediate life-threatening circumstance.

Since the dying process is frequently complicated by delirium, ELDVs risk being misidentified as pathological delirium or hallucinations by professionals and caregivers. 13 Moreover, within a reductionist, strictly biomedical approach to care, non-ordinary states, such as ELDVs, are often considered hallucinatory and comparable to delusional conditions. 14 Defining ELDVs as hallucinations can limit how professionals in hospice provide care, refuting to the patients a context for communication and expression that deserves to be listened to, understood, and investigated.

In this regard, Fenwick and Brayne 6 suggest that these ELDVs could represent spiritual moments originating from the innate human desire for communication and connection. As such, ELDVs concur with the patients’ meaning-making, influence existential well-being, and can play a role in preparation for death.3,6 Furthermore, ELDVs impact the dying person because of their emotionally intense content.

Correctly categorizing ELDVs may help professionals deal with patients’ existential distress. 15 It would allow a deep and intimate communicative space with the dying persons and offer hospice staff the possibility to understand better patients’ concerns, needs, and existential wishes.

Observing these phenomena from patients’ perspectives is desirable since it would provide professionals with an essential context for exploring the patients’ conditions-taken as a whole-without prejudices.

Purpose

Qualitative research shows how ELDVs are important for patients’ meaning-making. 16 At the same time, it doesn’t seem easy to reach the same conclusion using quantitative approaches such as questionnaires. There are no specific questionnaires for ELDVs. Likewise, the Greyson scale, 17 conceived for NDEs, does not take the ELDVs into proper and tailored consideration, even if it shows a reasonable degree of transferability to them. Furthermore, and particularly relevant in settings such as hospice care, the patients may perceive questionnaires as an impersonal tool that lays a distance between them and the observer, making it more challenging to investigate those features. Lastly, what matters most to patients maybe not always be included in quantitative research, 18 eg, for typically demanding inclusion/exclusion criteria or, more simply, because they cannot interact appropriately with strictly structured tools such as questionnaires. However, qualitative studies generally consist of small analyses that would benefit from aggregation and synthesis to highlight and summarize the overarching dimensions. This systematic review aims to aggregate, interpret, and synthesize the findings from the qualitative research literature 19 about ELDVs from the direct voice of patients assisted in hospice facilities and programs to indicate future directions for research and care.

Methods

Perhaps best known for quantitative research, it is possible to carry out systematic reviews and synthesize the information gathered from appropriately retrieved and selected qualitative studies. This technique is commonly referred to as meta-synthesis. So, a systematic review and meta-synthesis 19 were employed to collect all the qualitative studies, aggregate and interpret their findings. Qualitative meta-synthesis means “an interpretive integration of qualitative findings”. 19 We reached this secondary interpretation by taking only the patients voicing their experience of ELDVs (first-order constructs) and authors’ descriptions of primary studies’ results (second-order constructs), namely their accounts of patients’ narratives. The systematic review was previously registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021262559, available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021262559). We followed the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines for writing this review 20 (which is provided in the supplementary material).

Search Strategy

MEDLINE/PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were searched by MCB-an information specialist. The search strategy was based on a modified version of the PCC mnemonic (population, context, and concept). 21 We added the research design as a domain for questioning the databases. The population was patients in their end-of-life assisted hospice care (context) who had ELDVs (concept) regardless of their specific diseases but were limited to oncological cases only. We searched for exclusively qualitative studies whose data collection strategies included interviews, focus groups, and qualitative methods in general. In Table 1, we display the search strategy used for the MEDLINE database. The database search was performed on June 17th, 2021.

Table 1.

Search strategy (MEDLINE).

| Participants | (“Terminal Care” [MeSH] OR End of Life OR Terminal*) |

|---|---|

| AND | |

| Context | (Hospice* OR “hospice Care” [MeSH] OR “Hospices” [MeSH]) |

| AND | |

| Concept | (Dead bed vision* OR deadbed vision* OR death bed vision* OR deathbed vision* OR dream* OR mystical experience OR near-death phenomena OR near-death* OR tunnel sensation OR unusual perception OR vision* OR visitation* OR visitor* OR visual imagery OR fantas* OR illusion* OR hallucination* OR “Fantasy” [MeSH] OR “Illusions” [MeSH] OR “Hallucinations” [MeSH]) |

| AND | |

| Research type | (Qualitative research OR grounded theory OR empirical research OR qualitat* OR interview* OR behavior observation techniques OR ethno* OR focus groups OR phenomenol*OR “qualitative Research” [MeSH] OR “focus Groups” [MeSH] OR “grounded Theory” [MeSH] OR “interviews as Topic” [MeSH] OR “empirical Research” [MeSH] OR “behavior observation Techniques” [MeSH]) |

Two authors of this review (ER, MEDC) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant publications. Full texts were retrieved and evaluated by the same authors. A discussion with the MCB and LG solved discrepancies. Citation searching of the included articles was also performed to retrieve other relevant literature.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies collected terminally ill patients’ direct voices about their experience of ELDVs within hospice care. So, the inclusion criteria were: (i) primary qualitative studies, (ii) published in English, Italian, and Spanish with no time limits, and (iii) focusing on the experiences of ELDVs by hospice patients (>18 years old).

The exclusion criteria were: (i) editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, expert opinions, and literature reviews, (ii) mixed-method studies, whose qualitative results could not be analyzed separately from the quantitative results; and (iii) qualitative studies where participants’ voices were not considered.

Critical Appraisal

We assessed the methodological quality of the included articles using the modified Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist tool 22 to examine the study validity, adequacy, and applicability of the results. The CASP tool is a commonly used method to appraise studies in qualitative synthesis and considers research transparency and methodological appropriateness. Compared to the previous version, 23 this modified CASP qualitative checklist adds a question for assessing qualitative studies’ theoretical, ontological, and epistemological framework and suggests organizing the synthesis by prioritizing higher-quality studies. Each response in the CASP tool was assigned a numerical value (Yes = 1, Can’t tell = 0, Somewhat = 0, No = 0). A total score was calculated for each included study with a maximum possible score of 10. Retrieved articles were graded as high quality, medium to high quality, medium quality, low to medium, or low quality. Two authors (MEDC and ER) initially assessed the quality of the included articles. LG gave the third opinion and reviewed their assessment. Finally, all the authors agreed on the overall appraisal.

Data Extraction

We defined a data extraction table including the following studies’ characteristics: author(s) and year, country (where the study was conducted), working definitions of ELDVs, study’s aim, research setting, sample type and size, participants’ health conditions, data collection strategies, data analysis strategies, ethical issues, a summary of findings.

Data Synthesis

Following the approach suggested by Sandelowski and Barroso, 19 participants’ narratives were extracted manually from the “results/findings” sections and inserted into a table, along with the present second-order constructs. While participants’ narratives are first-order constructs, we considered second-order constructs descriptions of findings by the study’s authors. The entire dataset is available in the supplementary material. ER and MEDC, with the support of an external qualitative methodologist (LG), labeled narratives and authors’ descriptions to reduce meanings into manageable concepts. The authors then grouped the labels into themes. Those themes were discussed in several group meetings to reach an inter-coder agreement. By interpreting the relationship among those themes (taxonomic analysis), 19 we conceptualized a three-level model that explains the experience of having ELDVs in hospices. All the authors agreed upon the final version of this review’s findings.

Results

Literature Search and Characteristics of the Studies

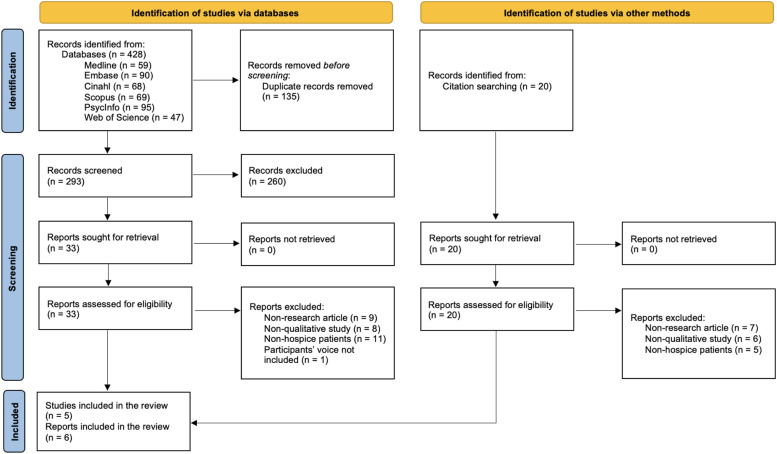

The database search yielded 293 documents after duplicates were removed. Then, we reviewed the reports by title/abstract, and 33 relevant articles were assessed in the full text against the inclusion criteria. Six qualitative articles,24–29 reporting on five unique studies conducted in hospice settings, were included in the meta-synthesis. The reduction from the initial series of 293 articles to the final six may seem very dramatic, but the order of magnitude is common to studies like ours. This datum may also reflect the health researchers’ restraint and embarrassment concerning patients being directly interviewed about their ELDVs. The selection process is summarized in Figure 1 as the PRISMA flow diagram. 30

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram.

Critical Appraisal Results

We critically evaluated all six studies to highlight their methodological strengths and weaknesses. Two articles were rated high quality, one medium quality, and three low quality. No articles were excluded for quality reasons. A summary of the scores is shown in Table 2, while the CASP evaluation is available in the supplementary material.

Table 2.

Studies' characteristics.

| First Author, year, Country | Working definition(s) of ELDVs | Aim(s) | Design | Setting | Sample Type and Size | Data Collection | Data Analysis | Ethical Issues | Summary of Findings | CASP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grant, 2014, USA | Since ancient times, people have recorded dreams and visions experienced by individuals at the end of their lives. Often during these dreams, the dying individual experiences deceased family, friends or religious figures | Document hospice patients’ ELDV experiences over time using a daily survey | Mixed-methods longitudinal study | Hospice inpatient unit | 59 hospice patients with cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, urinary tract infection | 453 interviews | Not reported | Sixty-six patients admitted to a hospice inpatient unit between Jan 2011 and Jul 2012 provided informed consent and participated in the study | Most participants reported at least one dream or vision and almost half of the dreams and visions occurred during sleep. Nearly all patients reported that their experience felt real. The most common content featured deceased friends and relatives, followed by living friends and relatives. As participants approached death, comforting dreams, and visions of the deceased became more prevalent | Low quality |

| Kerr, 2014, USA | These experiences may involve visual, auditory and/or kinesthetic experiences, with visions occurring during a wakeful state or dreams occurring during sleep. These end-of-life dreams and visions (ELDVs) are often deeply comforting and profoundly meaningful for patients and their families. These experiences can occur months, weeks, days or hours before death and typically reduce fear of dying, making transition from life to death easier for those experiencing them | Examine the content and subjective significance of ELDVs | ||||||||

| Relate the prevalence, content and significance of end-of-life experiences over time until death | ||||||||||

| Nosek, 2015, USA | End-of-life dreams and visions are well documented and have been reported throughout different cultures and recorded across history.5,12 people nearing the end of life often experience increasingly vivid and memorable dreams.12 this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that dreams, and visions are intrinsic to the transition from life to death.16 most research indicates that ELDVs occur near death with the time frame ranging from hours, days, weeks, or even months prior to death | To address the noted gap through direct patient interviews. To gain greater understanding of the ELDVs | Mixed-method design | Hospice inpatient unit | 63 hospice patients with cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic kidney disease, and other conditions | Interviews | Inductive content analysis | The study was reviewed and approved by the social and behavioral sciences institutional | Six categories emerged: Comforting presence, preparing to go, watching or engaging with the deceased, loved ones waiting, distressing experiences, and unfinished business | Medium quality |

| Review board of the state university of New York at buffalo (buffalo, NY) | ||||||||||

| Dam, 2016. India | End-of-life dreams and visions (ELDVs) are not uncommon and are experienced by many near the time of death. It is estimated that 50-60% of conscious dying patients experience ELDVs. The most prevalent ELDVs reported are those in which the dying patients describe seeing deceased family, friends, or religious figures. These visions can occur months, weeks, days, or hours before death | To assess the incidence and nature of ELDVs in India, with its rich cultural, spiritual, and religious heritage, and to compare the nature of ELDVs experienced between the rural and urban population | Prospective, cohort-based, with a mixed-methods research design | Home-based care in rural and urban settings of India | 60 patients were interviewed at home. The mean age was 55.16 years with a standard deviation of 17.30. There were more females (56.6%) than males. 30% were from rural settings. Cancer was the primary diagnosis in 81.6% cases | Close- and open-ended questions within a questionnaire. The interview was carried out in an unhurried manner with minimal disturbance as far as practicable, in Bengali, Hindi, or English | Content analysis | Not reported | ELDVs are not uncommon in India and the incidence does not differ significantly between rural and urban population. The participants found them to be distressing initially, but felt better after discussing it with the team. There was a direct correlation between severity of symptoms and occurrence and frequency of ELDVs. The persons visualized in ELDVs did not threaten or scare the patient and the known persons visualized were seen as they were in their prime of health | Low |

| Nyblom, 2021, Sweden | One aspect of spirituality that has been reported in and fascinated many cultures throughout history are phenomena occurring months to hours before death,7-10 termed end-of-life experiences (ELEs). These experiences can be visual, auditory and/or kinesthetic,8 often including visions of deceased loved ones while awake or vivid dreams during sleep.9,11,12 experiences of going on journeys are prevalent and interpreted by some as the approach of death.7 in the majority of cases they are perceived as positive, meaningful8,9 and, in helping patients prepare for their impending death,8,13 inherent to the process of dying | To investigate if end-of-life experiences in the form of dreams, visions and/or inner experiences, are reported directly by Swedish patients, oriented in time, place and person and receiving palliative end-of-life care. If so, what do ELEs contain and what are patients’ subjective experiences of them | Qualitative study | Advanced end-of-life palliative care at home or in three hospice inpatient units | 25 end-of-life patients (with cancer) admitted to advanced end-of-life palliative care at home or in three hospice inpatient units | One-on-one, face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews | Qualitative content analysis | This study was approved by the regional ethical review board in gothenburg (no. 999-17; date of approval: 2018-02-12) | Four themes were identified: Vivid dreams while asleep, experiences while awake, references to medical circumstances and communication about end-of-life experiences. Prevalent content was deceased and living loved ones and journeys. Some patients distinguished between hallucinations/nightmares and end-of-life experiences | High quality |

| Wright, 2015, USA | The limited data regarding end-of-life dreams suggest that they often reflect issues of grief and loss brought on by approaching death. Studies also suggest that these experiences include common themes such as seeing deceased loved ones sitting by the bedside or coming to take the dying person away, resolution of psychological “baggage,” and comfort in the face of death. These studies describe commonalities in the manifestation and impact of dreams at the end of life and suggest that vivid dreams are not only common during the dying process but may also influence existential well-being and may play a role in psychological preparation for death. Palliative care clinicians often view dreaming as an intrinsic part of the dying process, which assists people in reconciling their lives, completing “unfinished business,” and coming to terms with approaching death | To conduct a preliminary exploration into the process and therapeutic outcomes of meaning-centered dreamwork with hospice patients | Mixed methods | Hospice | 7 hospice patients with lung cancer, colon cancer, ovarian cancer, cerebellar ataxia, adult failure to thrive, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Audio-recorded longitudinally dream-work sessions | Consensual qualitative research (CQR) method (hill, C.E. (ed.). (2012). Consensual qualitative research: A practical resource for investigating social science phenomena. Washington, DC: American psychological association.) | This study was approved by the institutional review board at the state university of New York at buffalo | Participants’ dreams generally featured familiar settings and living family and friends. Reported images from dreams were usually connected to feelings, relationships, and the concerns of waking life. Participants typically interpreted their dreams as meaning that they needed to change their way of thinking, address legacy concerns, or complete unfinished business. Generally, participants developed and implemented action plans based on these interpretations, despite their physical limitations. Participants described dream-work sessions as meaningful, comforting, and helpful. High scores on a measure of gains from dream interpretations were reported, consistent with qualitative findings. No adverse effects were reported or indicated by assessments | High quality |

Findings

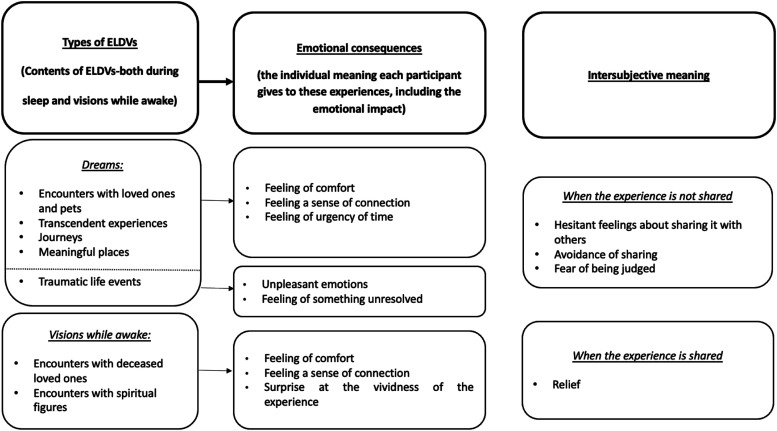

We generated three main categories through the meta-synthesis: (i) typologies of ELDVs reported, (ii) emotive consequences and (iii) intersubjective meaning-making.

These three categories account for (i) the contents of the ELDVs-both during sleep and vigilance-reported by participants in the included articles, (ii) the meanings each participant gave to these experiences, including the emotional impact, and finally, (iii) intersubjective meaning-making, just sketched by the available data.

We then interpreted these three categories in relation to each other within a conceptual model, which is visualized in Figure 2. Bringing out ELDVs meant listening to participants connect modalities and content with the meaning they experienced and constructed at the individual level. However, the dynamics of meaning would also involve a broader, expanded level. The ELDVs reported were experiences that remained intimate and unsocialized and thus preventing participants from defining a shared sense in their relationships. Participants stated they desired to share ELDVs with their family members and caregivers because ELDVs were real and vivid experiences, not credited to fantasies or imagination.

“It is not a dream, it’s reality (…) When she shows up [in the dreams] they are real, they are (…) I am aware of that he is sitting beside me” 24

“I am not going alone-[my sister] will be with me” 25

Figure 2.

Meta-synthesis conceptual model.

According to participants in Dam, 29 ELDVs could occur at any time of the day.

“They come mostly at night, but then there is no fixed time… I have seen him in day time as well” 29

Typologies of ELDVs

Participants reported both ELDVs they had during sleeping and while they were awake.

As to dreaming ELDVs, different contents were reported:

− Encounters (both deceased and living loved ones, pets).

− Transcendental experiences.

− Travels.

− Places.

− Traumatic events.

Most ELDVs Depicted Encounters with Loved Ones

“I was raking leaves in the back of the house, and my [deceased] husband came through the sideyard. I asked him, ‘where have you been so long?’ and he just said, ‘I am sorry I have to leave you for a while” 26

Barbara dreamt of her deceased father and brothers, hugging her and ‘welcoming her to the dead’. They seemed to be preparing to go somewhere, but ‘they haven’t said where’ 27

“Tim had dreams that included his deceased parents, grandparents, and old friends who were ‘telling me I will be okay. I haven’t seen some of these people for years’, he stated” 27

Three days before another woman died, she reported experiencing both waking visions and dreams of being at the top of a staircase with her dead husband “waiting” for her at the bottom of the staircase. 25

Worthy to note is that persons in visions and/or dreams were not intimidating or scaring, even if this was some patient’s reaction.

“They never harm or frighten me. They are always smiling…” 29

Other dreams concerned encounters with one’s pets, for example:

“Emily reported frequent and comforting dreams of playing with her childhood dog Sparky. She continued to have dreams featuring Sparky until she improved clinically, and her dreams stopped” 27

When participants reported they dreamed of deceased loved ones, they typically appeared younger and healthier:

“They have not aged […] Beautiful and very healthy” 24

“My mother died of cancer. But, when I see her at night, she looks fresh, healthy, and wearing nice clothes” 29

In some narratives, participants also reported that the dreamed persons were silent, watching the participants, and not performing any activity:

“No, not directly spoke, no. We shared something with each other” 24

“I was scared and confused… She had died six months back… How could she be sitting next to me and smiling at me?” 29

Several participants reported encounters with undefined or transcendental figures. In Kerr, a participant said to have dreamed of two babies among blue and white lights, 27 while another described an encounter with God:

“Megan reported a dream in which God held her hand. She stated, ‘I am ready to die. I just want to go peacefully’” 27

Some participants dreamed of traveling with no specific destination.

“I know we are going somewhere, but don’t know where” 27

Participants describing travels conveyed a feeling of urgency:

“You are leaving in five minutes, and you have not packed” 24

Another dream-related content was about places: familiar places (childhood homes), locations visited during holidays, or transfigured/transcendent settings.

“I was sitting in a garden where everybody was peaceful and serene and just going about their business” 26

“Laurene had dreams of her mother in a beautiful garden saying, ‘Everything will be okay.’ She told her family she wanted to sleep as her mother will return” 27

Some participants reported dreams about traumatic events like abuses 25 or war incidents.24,27

As to the ELDVs while awake, participants reported they had met persons, particularly deceased loved ones and spiritual/unknown figures.

“Audrey reported seeing ‘five little angels’ in her room and immediately told a priest she was ready to die and wanted to write a letter to God” 27

Emotive consequences

Reported ELDVs were reported by participants as significant experiences accompanied by emotions (positive and negative).

Cheerful emotional tones were triggered by the encounters with persons (in dreams and visions), causing a strong sense of connection. Participants reported they were comforted by meeting passed loved ones or spiritual figures, bringing a sense of reassurance.

“I’m not afraid of death, definitely not” 24

Unpleasant emotions were mainly reported when visions were associated with hallucination-like experiences or lived traumatic/unsolved issues. Participants charged frightening and confusing visions to the drugs’ effects.

“To me, it feels like I get hallucinations from it [oxycodone] seeing a jellyfish up in that corner over there” 24

Furthermore, painful past experiences (stressful family matters or war-related/unresolved things) and worrying future inevitable events (the own death or funeral planning) related to negative feelings.

“I woke up at 4:30 this morning, and I was having a nightmare about the urgency to fill out this packet I have to fill out for the funeral parlor for my last Mass at church with the family” 26

The vividness of ELDVs and their related emotions lingering after pushed some participants to deal with the unresolved issue once they were awake. 26

Wanting intersubjective meaning-making

Participants reported how sharing the experience of ELDVs with others was difficult for fear of being judged or not being understood.

“I don´t talk about such things with them” 24

Nonetheless, some data suggested that when participants tried to disclose, they were surprised to realize the stake and listening from their loved ones.

Patients felt relieved talking about ELDVs with professionals, taking this as a possibility of re-elaborating the meanings and feeling supported in their end-of-life journey. Especially for those patients reporting that they were clueless about the significance of their dreams.

“I don't understand why I see them… I have never seen them before, so why now?” 29

“It’s very meaningful because I am here at the end of my life. Talking about the dream helped me explore and put thought into it. I feel good. I liked discussing the dream. Talking about it gave it more meaning” 26

Discussion

Our study is in the wake of a recent systematic integrative review by Hession and colleagues, 31 but, unlike Hession’s, considers only qualitative studies concerning articles giving voice to hospice patients who experienced ELDVs.

Our conceptual model summarizes how ELDVs can play an important role in death trajectories. Firstly, dreams and visions have meanings that hospice patients greatly value. Moreover, based on the content of ELDVs, emotions may vary but still underline that ELDVs are critical and may enrich end-of-life moments. Finally, sharing these experiences triggers ambivalent sentiments from fear of being judged to relief.

While awake, participants reported encounters with deceased family members, pets, and spiritual figures. Other visions entailed evocative and meaningful places (such as a garden or the family of origin’s home). The theme of traveling and packing frequently appeared, according to the voice of the participants. While dreaming, we summarized positive and negative subjects (eg, the war in those who experienced it many years before) that significantly impacted participants’ lives. Some unpleasant emotional dreams have been reported as caused by unresolved life events or episodes of confusion that the patients later traced back to medication or organic causes. Despite some fearing situations, 29 most participants reported that the ELDVs reassured them, making them feel connected to the figures encountered.

Regarding the intersubjective dimension, our findings align with the existing literature,1,2,32 confirming that hospice patients often avoid reporting these experiences for fear of ridicule 33 and embarrassment. When shared with others, there is a tendency to downplay ELDVs by letting the topic drop. Patients whom healthcare professionals and caregivers stimulated to talk about these experiences felt comfortable 34 and more inclined to deal with complex existential issues, as reported in a recent secondary qualitative study on dreams’ metaphors. 35

Intersubjectivity helps meaning-making: the importance for healthcare professionals and caregivers supporting this process is beyond doubt. 36 Training healthcare professionals to recognize ELDVs and take advantage of them in the care relationship is desirable and recently recommended. 37 Accordingly, we also encourage the patient’s family members to listen and understand ELDVs when they occur actively.

Being trained for dealing with ELDVs proactively engage professionals and caregivers with their identification and normalization. 37 Welcoming ELDVs means addressing the actual experience of a dying patient. As highlighted, 7 healthcare professionals engaging with ELDVs, as these experiences are psychologically significant, can provide a source for clinical insight and avoid dismissing them as alterations of cognition (eg, delirium). 1 Moreover, for caregivers to know how to interpret these phenomena may provide them with additional strategies for supporting, reassuring and strengthening the relationship with their loved ones. 34

This review leads us to assert that the first repositories of the meaning of ELDVs are the patients themselves, as advocated by Janssen, 33 who invites professionals to let “patients and families interpret deathbed phenomena for themselves”, aligning with recommendations for healthcare professionals. 37 They should be listened to and embraced in their experiences as they are the foremost experts: many can recognize ELDVs and discriminate them from delirium and hallucinations. In ELDVs there is no “blackout” of physical and psychological functions as in NDEs because the impairment, should it exist, is less severe organically than in NDEs. In this sense, ELDVs are a process and not the byproducts of an acute event. Consequently, it is not so much to focus on the organic causes of such mental phenomena as to accommodate them in the sense that people themselves make of them.

According to Grant and colleagues, 37 training for professionals, hopefully, shared with family members, should focus on strategies and skills for validating and normalizing ELDVs, building rapport and trust through empathy, continuing to be an active listener and, as already highlighted, allowing for the patient (and caregivers together) to interpret the experience. To stimulate a dialogue about ELDVs with patients, professionals and caregivers can, for example:

- Agree on the approach to adopting to allow patients to express these experiences (for instance, they must avoid the patients feeling misunderstood and ridiculed).

- Show interest in patients’ dreams or visions, letting them verbalize their associated emotive status and meanings.

- Explore hospice patients’ quality of sleep by asking direct questions about dreams or other experiences they may be having.

Suppose healthcare professionals/caregivers realize that ELDVs are a source of spiritual and psychosocial stress. In that case, they should provide a timely holistic, and shared strategy to alleviate the patient’s suffering. 38 It will then be essential to consent to the patient’s access to the most appropriate professional figure. Nonetheless, healthcare professionals lack training in this field, suggesting this is a research relaunch for the future.

In conclusion, studying ELDVs can be revealing in itself because they present characteristics similar to those of NDEs, but in the absence of the physical and psychological impairments typical of a straightaway nearness to death, they could be supported by physiological mechanisms other than those typically invoked for NDEs. Postulating plausible causative hypotheses is difficult. However, considering the many common aspects in the contents of the two types of experiences, these unknown causes could explain, in a different way from those suggested up to now, the same NDEs: at least for the many common aspects. In this regard, if the context of cardiopulmonary resuscitation represented the setting of choice for the study of NDEs, 10 our review would seem to suggest that hospices (facilities and programs) could play a similar role for ELDVs, up to the hypothesis that ELDVs represent the peculiar form in which NDE-like experiences occur in hospice care.

Strengths and Limitations

The qualitative evidence synthesis on ELDVs in hospice settings allowed us to inform healthcare professionals how to support patients in sharing their emotional and identity-related experiences and meaning-making in end-of-life. Synthesizing hospice patients’ voices helped us identify the meaning for them of sharing ELDVs without feeling judged and being free to ask questions and process these experiences during their end-of-life path. Nonetheless, given the small number of studies identified, the offered perspective and the resulting implications on the end-of-life experience for patients and families are thin. Most of the included studies were conducted in the US; our findings should be considered informative, especially for western societies. Still, more qualitative research is needed to make cultural differences and nuances emerge. Finally, our results give insights into cancer patients in hospice care, regardless of treatments. The effects of treatments may have had a role in ELDVs, but we limited the scope of this review to meanings rather than etiology.

Footnotes

Author Contribution: All authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Health-Ricerca Corrente Annual Program 2024.

ORCID iDs

Silvio Cavuto https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2845-9310

Luca Ghirotto https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7632-1271

References

- 1.Mazzarino-Willett A. Deathbed phenomena: Its role in peaceful death and terminal restlessness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(2):127-133. doi: 10.1177/1049909109347328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kellehear A. Visitors at the End of Life. New York: Columbia University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenwick P, Lovelace H, Brayne S. End of life experiences and their implications for palliative care. Int J Environ Stud. 2007;64(3):315-323. doi: 10.1080/00207230701394458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellehear A. Unusual perceptions at the end of life: Limitations to the diagnosis of hallucinations in palliative medicine. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(3):238-246. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-001083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brayne S, Lovelace H, Fenwick P. End-of-Life experiences and the dying process in a gloucestershire nursing home as reported by nurses and care assistants. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25(3):195-206. doi: 10.1177/1049909108315302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenwick P, Brayne S. End-of-life experiences: reaching out for compassion, communication, and connection-meaning of deathbed visions and coincidences. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(1):7-15. doi: 10.1177/1049909110374301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Depner RM, Grant PC, Byrwa DJ, et al. Expanding the understanding of content of end-of-life dreams and visions: A consensual qualitative research analysis. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1(1):103-110. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Claxton-Oldfield S. Distressing deathbed visions: rare, misunderstood, or underreported? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;23:104990912311524. doi: 10.1177/10499091231152441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greyson B, Stevenson I. The phenomenology of near-death experiences. Am J Psychiatr. 1980;137(10):1193-1196. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.10.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parnia S, Post SG, Lee MT, et al. Guidelines and standards for the study of death and recalled experiences of death-a multidisciplinary consensus statement and proposed future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2022;1511(1):5-21. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greyson B. Varieties of near-death experience. Psychiatry. 1993;56(4):390-399. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parnia S, Spearpoint K, de Vos G, et al. AWARE-AWAreness during REsuscitation-a prospective study. Resuscitation. 2014;85(12):1799-1805. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brayne S, Farnham C, Fenwick P. Deathbed phenomena and their effect on a palliative care team: A pilot study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(1):17-24. doi: 10.1177/104990910602300104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grof S. Beyond the Brain: Birth, Death, and Transcendence in Psychotherapy. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyblom S, Molander U, Benkel I. End-of-life dreams and visions as perceived by palliative care professionals: A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2022;20:801-806. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1017/S1478951521001681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblit G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: Reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14(10):1342-1365. doi: 10.1177/1049732304269888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greyson B. The near-death experience scale. Construction, reliability, and validity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171(6):369-375. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198306000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sandelowski M, Barroso J, Voils CI. Using qualitative metasummary to synthesize qualitative and quantitative descriptive findings. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(1):99-111. doi: 10.1002/nur.20176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, Oliver S, Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res Methods Med Health Sci. 2020;1(1):31-42. doi: 10.1177/2632084320947559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Critical Appraisals Skills Programme . CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist; 2018. Published online https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Accessed June 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyblom S, Arnby M, Molander U, Benkel I. End-of-Life experiences (ELEs) of spiritual nature are reported directly by patients receiving palliative care in a highly secular country: A qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(9):1106-1111. doi: 10.1177/1049909120969133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nosek CL, Kerr CW, Woodworth J, et al. End-of-Life dreams and visions: A qualitative perspective from hospice patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(3):269-274. doi: 10.1177/1049909113517291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright ST, Grant PC, Depner RM, Donnelly JP, Kerr CW. Meaning-centered dream work with hospice patients: A pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(5):1193-1211. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514001072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr CW, Donnelly JP, Wright ST, et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: A longitudinal study of hospice patients’ experiences. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(3):296-303. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant P, Wright S, Depner R, Luczkiewicz D. The significance of end-of-life dreams and visions. Nurs Times. 2014;110(28):22-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dam AK. Significance of end-of-life dreams and visions experienced by the terminally ill in rural and urban India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22(2):130-134. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.179600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hession A, Luckett T, Chang S, Currow D, Barbato M. End-of-life dreams and visions: A systematic integrative review. Palliat Support Care 2022;1-10. Published online. doi: 10.1017/S1478951522000876 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Barbato M, Blunden C, Reid K, Irwin H, Rodriguez P. Parapsychological phenomena near the time of death. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(2):30-37. doi: 10.1177/082585979901500206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janssen S. Letting patients and families interpret deathbed phenomena for themselves. Am J Nurs. 2015;115(9):11. https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/Fulltext/2015/09000/Letting_Patients_and_Families_Interpret_Deathbed.2.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wholihan D. Seeing the light: end-of-life experiences-visions, energy surges, and other death bed phenomena. Nurs Clin. 2016;51(3):489-500. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nyblom S, Molander U, Benkel I. Metaphors in end-of-life dreams in patients receiving palliative care: A secondary qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2023;40:74-78. Published online April 29, 2022. doi: 10.1177/10499091221090625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Claxton-Oldfield S. Deathbed visions: visitors and vistas. Omega 2022;0(0):1-16. Published online April 29, 2022. doi: 10.1177/00302228221095910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grant PC, Levy K, Rossi JL, Lattimer TA. End-of-Life dreams and visions: Initial guidelines and recommendations to support dreams and visions at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2023;5:2023. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinar YR, Marks AD. Distressing visions at the end of life: Case report and review of the literature. J Pastor Care Counsel. 2015;69(4):251-253. doi: 10.1177/1542305015616103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]