Abstract

Background:

Preclinical models of cocaine use disorder (CUD) have not yielded any FDA-approved pharmacotherapies, potentially due to a focus on cocaine use in isolation, which may not fully translate to real-world drug taking patterns. Cocaine and nicotine are commonly used together, and clinical research suggests that nicotine may increase the potency and reinforcing strength of cocaine. In this study, we sought to determine whether and how the addition of nicotine would alter ongoing intravenous cocaine self-administration and motivation to take cocaine in rats.

Methods:

Male Sprague-Dawley rats self-administered cocaine alone on a long access, Fixed Ratio one (FR1) schedule, and then switched to a combination of cocaine and nicotine. Finally, rats responded on a Progressive Ratio (PR) schedule for several doses of cocaine alone and in combination with a single dose of nicotine.

Results:

Under long access conditions, rats co-self-administering cocaine and nicotine responded less and with decreased response rates than for cocaine alone and did not escalate responding. However, under PR conditions that test motivation to take drugs, the dose response curve for the combination was shifted upwards relative to cocaine alone.

Conclusions:

Together, these results suggest that nicotine may enhance the reinforcing strength of cocaine, increasing PR responding for cocaine across the dose response curve.

Keywords: Cocaine, Nicotine, Self-administration, Polysubstance use

1. Introduction

Cocaine use disorder (CUD) is a complex disorder characterized by compulsive drug-seeking, withdrawal, craving, and recurrent use. While there have been more than 300 clinical trials examining potential treatments for CUD, none have resulted in an FDA-approved pharmacotherapy (NIDA, 2020). Prior to clinical trials, potential medications are often examined in preclinical self-administration studies, which are used to identify and screen potential pharmacological candidates for safety and efficacy. However, many preclinical studies examine a single drug in isolation, which often does not represent the substance use patterns of people in clinical populations (Kedia et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2019; Roy et al., 2013). Rodent self-administration of cocaine alone, for instance, likely does not encapsulate the complexities of clinical CUD, as people with CUD frequently present with polysubstance use, including concurrent use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, opioids, and other drugs (Compton et al., 2021; John and Wu, 2017). In particular, nicotine is commonly used in combination with cocaine, with a two- to four-fold higher prevalence of cigarette smoking in individuals with CUD than in the general population (Budney et al., 1993). Further, clinical studies suggest that cocaine and nicotine co-use may lead to increased consumption of both substances, measured both as total consumption and rate of consumption (Roll et al., 1996).

Psychomotor stimulants produce their reinforcing effects via activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system, particularly dopaminergic neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc). However, the mechanisms by which cocaine and nicotine increase dopamine differ, which may contribute to synergistic interactions between these two substances. Cocaine primarily acts at the dopamine transporter (DAT), increasing extracellular dopamine levels by binding to and inhibiting the DAT, thereby preventing the transport of dopamine from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic terminal (Loland et al., 2004; Ritz et al., 1990). This elevation of extracellular dopamine concentration has been directly linked to cocaine’s reinforcing properties (Ritz et al., 1987; Roberts et al., 1977, 1980; Shan et al., 2011). Chronic cocaine exposure has been shown to cause long-term disruptions to the dopamine system, resulting in decreased extracellular dopamine. In contrast, nicotine increases extracellular dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic dopamine system by activating excitatory nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) on dopamine cell bodies in the VTA and dopamine terminals in the NAc (Wonnacott, 1997). As cocaine and nicotine have distinct mechanisms of action to increase dopamine activity within the mesolimbic system, it is likely that concurrent use of these two substances would result in heightened levels of extracellular dopamine when compared to use of either substance alone (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988; Pich et al., 1997; Pontieri et al., 1996).

A critical factor in the initiation and continuation of substance use disorders is the presence of environmental and drug-associated cues. Nicotine self-administration has been shown to be highly driven by the presence of drug-associated cues, more so than self-adminstration of cocaine or other substances (Butler et al., 2021; Caggiula et al., 2009, 2001; Chaudhri et al., 2007; Donny et al., 1995, 2003; LeSage et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2006; Sorge et al., 2009). The cue-dependent nature of nicotine self-administration makes behavioral extinction more difficult, as the response behavior is strongly driven by cues (Clark et al., 2001; Elias et al., 2010) and may contribute to the low effectiveness of smoking cessation treatments. Evidence suggests that nicotine augments the salience of drug-related cues by enhancing dopamine release during phasic (burst) activity (Rice and Cragg, 2004), thereby facilitating reward-related dopamine signaling. This alteration to phasic firing patterns may enhance the salience of other drug-associated cues and support the development of habitual behaviors (Asgaard et al., 2010; Claus et al., 2013; Lê et al., 2003; Overby et al., 2018). In the context of polysubstance use, these alterations may contribute to increased cocaine-related responding.

In clinical populations, concurrent use of cocaine and nicotine results in faster consumption and greater intake of both substances (Brewer et al., 2013; Budney et al., 1993; Kalman et al., 2005; Roll et al., 1996; Sigmon et al., 2003; Wiseman and McMillan, 1996). The idea that increases in substance-use behavior may be facilitated by the greater reinforcing value of concurrent cocaine and nicotine is supported by findings of higher self-reported positive subjective drug effects following combined use (Brewer et al., 2013; Wiseman and McMillan, 1998). Preclinically, nicotine has had variable effects when combined with cocaine. Across a variety of animal species and drug self-administration schedules, acquisition of cocaine self-administration is increased and responding for cocaine is enhanced following noncontingent intraperitoneal (i.p.) or subcutaneous (s.c.) pretreatment with nicotine (Bechtholt and Mark, 2002; Freeman and Woolverton, 2009; Horger et al., 1992; Mello and Newman, 2011; Schwartz et al., 2018). However, while one study found that nicotine could reinstate previously extinguished cocaine responding (Bechtholt and Mark, 2002), such results have not been consistent (Schenk and Partridge, 1999). Additionally, nicotine has been shown to substitute for cocaine in rodent models of drug discrimination (Desai et al., 1999), but this effect has not been recapitulated in non-human primate drug discrimination models (Mello and Newman, 2011).

In preclinical studies, multiple schedules of reinforcement are needed to assess the reinforcing efficacy and motivation to take drugs versus the abuse potential of the drugs. As such, the present study uses both Fixed Ratio (FR) and Progressive Ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement. FR schedules of reinforcement, in which a specific, set number of responses is required to obtain a reinforcer, can help determine the presence of a reinforcing effect. For instance, drugs that produce robust responding on an FR schedule are considered to have abuse potential; however, it is difficult to determine relative reinforcing strength of different drugs using this method (Arnold and Roberts, 1997; Panlilio and Goldberg, 2007). To compare reinforcing strength of a drug between conditions, PR schedules of reinforcement are used. During PR schedules, the number of responses required to obtain each subsequent drug infusion increases systematically, thereby increasing the effort required to obtain an infusion of drug. The outcome measure is called the breakpoint, and is the infusion earned with the highest response requirement. Due to this, PR schedules are often used as a test of motivation in behavioral neuroscience, as animals with higher breakpoints complete larger ratios (number of lever responses) to receive a single reinforcer (Panlilio and Goldberg, 2007; Richardson and Roberts, 1996).

Despite decades of preclinical research on the effects of nicotine or cocaine in isolation and non-contingent nicotine pretreatment prior to cocaine self-administration, only limited research has been conducted regarding concurrent, contingent nicotine and cocaine in animal models (Barbosa-Mendez and Salazar-Juarez, 2018; Freeman and Woolverton, 2009; Mello et al., 2013, 2014; Mello and Newman, 2011), which represents a more clinically translational model of CUD. Here, we used concurrent self-administration of cocaine and nicotine under FR1 and PR schedules to determine how the addition of nicotine modulated cocaine self-administration behavior. Results from this study suggest that concurrent self-administration of cocaine and nicotine may increase the reinforcing strength of cocaine, with decreased rates of long access responding and increased progressive ratio responding.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Eight male Sprague-Dawley rats (350–400 g; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) were maintained on a 12:12 hour reverse light/dark cycle (0300 off; 1500 on) with ad libitum food and water. All animals were maintained according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care accredited facilities. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

2.2. Drugs

Cocaine HCl was acquired from the National Institute on Drug Abuse Drug Supply Program (Bethesda, MD) and dissolved in sterile saline. (−)-Nicotine hydrogen tartrate salt (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was dissolved in sterile saline and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. All solutions were filtered prior to use in self-administration studies.

2.3. Apparatus

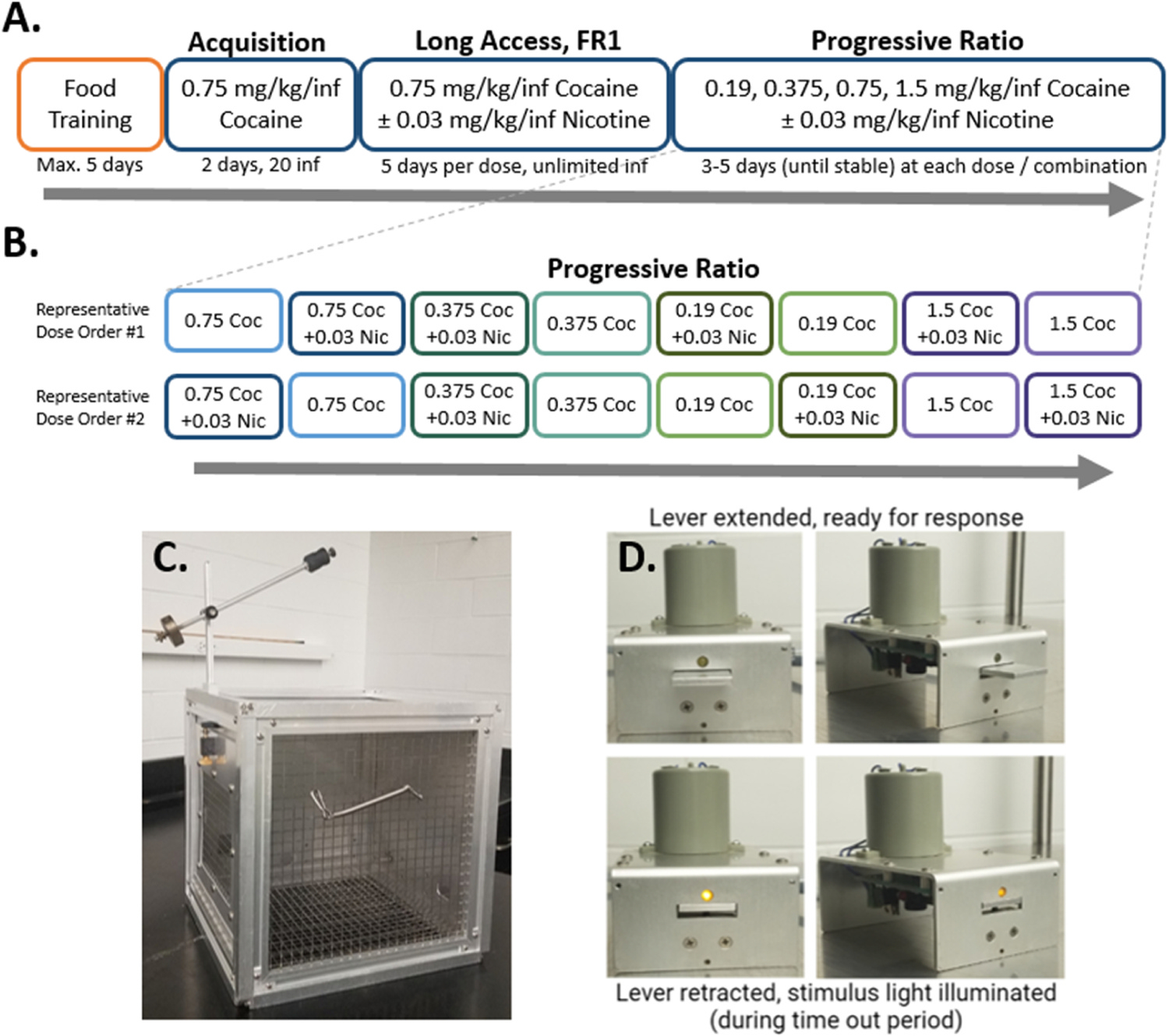

Rats were housed and trained in custom-made operant conditioning chambers located within the standard housing room (Fig. 1C). During all sessions, an active lever response resulted in retraction of the lever and illumination of the stimulus light, located directly above the lever, during the timeout (Fig. 1D). All sessions were completed during the dark cycle (0900–1500), and sessions occurred seven days per week. During food training only, a pellet hopper was attached to the left side of the chamber where pellets were automatically dispensed.

Fig. 1. Experimental timeline and self-administration apparatus.

A) Experimental timeline of behavioral procedure. During the Long Access phase, all rats were exposed to cocaine alone first, then cocaine + nicotine, five days per dose combination. The order of presentation of cocaine alone or cocaine and nicotine combination during progressive ratio responding was randomized for each rat individually. B) Representative progressive ratio dose orders for two rats. C) Example of custom-made operant conditioning and housing chamber, with counterbalance and tether. D) Example of lever apparatus, with lever extended (upper row) and retracted (lower row). The stimulus light, located immediately above the lever, is illuminated during the time out period.

2.4. Food training

One week after arrival, rats were individually housed and trained to self-administer sucrose pellets (45 mg) on an FR1 schedule (4 second timeout, 75 pellet maximum, 6 hour sessions). Rats met training criteria once a minimum of 50 pellets were earned with at least a 2:1 preference for the active over inactive lever. Positions of active and inactive levers were randomly assigned for each rat before food training began, and were maintained throughout the entire experimental paradigm. Rats that did not meet the criteria within five sessions were removed from the study (N=1).

2.5. Self-administration surgery and training

Three to five days following their last food self-administration session, rats were anesthetized (ketamine 100 mg/kg, i.p.; xylazine 10 mg/kg, i.p.) before implantation with a chronic indwelling jugular catheter as described previously (Liu et al., 2005). Following surgery, and for a two-day recovery period, rats were administered the NSAID meloxicam (1 mg/kg, s.c.) as a postsurgical analgesic, and flushed twice daily with heparinized saline. After recovery, animals were trained to self-administer cocaine on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement with a 20 second timeout period. Each lever press resulted in the intravenous delivery of 0.75 mg/kg/inf cocaine over four seconds. During training, rats could earn up to 20 infusions per 6 hour session. Acquisition criteria was considered met when an animal responded for 20 infusions for two consecutive days. Catheters were manually flushed with heparinized saline between doses and reinforcement schedules, as well as at the end of the study to ensure patency, defined by smooth, resistance-free depression of the syringe and a detectable behavioral response (including locomotion, rearing and/or stereotypical grooming or chewing) to infusion of cocaine or cocaine + nicotine.

2.6. Long access

Rats were allowed unlimited access (FR1) to 0.75 mg/kg/inf cocaine during 6 hour sessions for five consecutive days. Starting the next day, all animals were allowed unlimited access (FR1, 4 second timeout) to the combination of 0.75 mg/kg/inf cocaine + 0.03 mg/kg/inf nicotine under the same conditions for a further five days (see Fig. 1A). Cocaine and nicotine were administered concurrently via the same syringe and intravenous catheter.

2.7. Progressive ratio (PR)

Rats self-administered drug on a PR schedule, where the outcome measure used was the total number of infusions earned within a 6 hour session. During each daily PR session, response requirements systematically increased following each earned reinforcer in the following ratio sequence: 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, etc., as described previously (Karkhanis et al., 2016). Cocaine doses were administered to each rat in the same pseudorandom order (0.75, 0.375, 0.19, 1.5 mg/kg/inf). Each cocaine dose was also combined with 0.03 mg/kg/inf nicotine. The pairs of cocaine-alone/cocaine+nicotine solutions at each cocaine dose were offered sequentially, with random assignment of whether cocaine-alone or cocaine-nicotine combination was offered first. No two rats received the same presentation order (for example presentation orders, see Fig. 1B). When a rat transitioned to a new dose/combination, they continued at that dose until responding was stable (three days with ≤ 20% change in total number of infusions earned) or a maximum of five days, before moving to the next dose/combination. All rats received all cocaine and cocaine + nicotine doses (8 total). The total number of days of PR responding varied between 27 and 40, depending on how quickly stable responding was reached at each dose/combination. One rat was excluded, as PR responding did not stabilize on any cocaine dose or cocaine + nicotine combination.

2.8. Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 (Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data are presented as mean ± SEM, significance level p < 0.05. Repeated measure two-way ANOVAs were used to determine significance, followed by Sidak’s post-hoc tests as appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition of food and cocaine self-administration

Prior to acquisition of cocaine self-administration behavior, animals were trained to respond on an FR1 schedule of reinforcement for sugar pellets. Acquisition criteria for the food self-administration task was set at one day where a minimum of 50 active lever responses were obtained with a 2:1 ratio of active to inactive lever responses. Seven animals acquired food self-administration behavior, with a mean of 3.1 days ± 0.77 to reach criteria (Fig. 2A). All animals that acquired food self-administration also acquired cocaine self-administration (0.75 mg/kg/inf, FR1) with a mean of 2.4 days ± 0.30 to reach criteria (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Food-training and cocaine self-administration acquisition.

A) Percent of rats that met food-training criteria within five days. Mean (± SEM) number of sessions required to reach criteria was 3.1 days (± 0.77), N=7. Rats that did not meet criteria within five days were excluded (N=1). B) Percent of rats (which had previously met food-training criteria) that met cocaine acquisition criteria by day. Mean (± SEM) number of sessions required to reach acquisition criteria, 2.4 days (± 0.30), N=7.

3.2. Concurrent cocaine + nicotine self-administration decreased responding compared to cocaine alone and prevented escalation of cocaine-taking behaviors

To determine if rats would self-administer concurrent cocaine + nicotine equivalently to cocaine alone, we used an FR1 long access self-administration paradigm. Significant main effects of session (F4,24=2.957, p=0.0405) and nicotine condition (F1,6=27.26, p=0.0020) were observed across the five days of long access self-administration, with a significant interaction of session X nicotine condition (F4,24=5.089, p=0.0041; Fig. 3A&A’). Sidak post-hoc tests revealed a significant increase from session 1 to session 5 of cocaine alone responding (t(7,24)=4.492, p=0.0015), but no significant change from session 1 to session 5 of cocaine + nicotine responding (t(7,24)=0.4390, p>0.9999). Average rate of responding on days 3 through 5 of cocaine alone self-administration (13.73 ± 0.627 inf/hr) was significantly greater (t(6)=3.359, p=0.0153; Fig. 3B) than average rates of responding on days 3 through 5 of concurrent cocaine and nicotine self-administration (11.95 ± 0.556 inf/hr). Further, responding on day 1 of concurrent cocaine + nicotine was not significantly different than responding on day 1 of cocaine alone (t(7,24)=0.1689, p>0.9999; Fig. 3C), but responding on day 5 of concurrent cocaine + nicotine was significantly lower than responding on day 5 of cocaine alone (t(7,24)=5.100, p=0.0002; Fig. 3C). Escalation was observed during cocaine alone responding, as responding on day 5 of cocaine alone was significantly greater than responding on day 1 (t(7,24)=4.492, p=0.0015; Fig. 3C). In contrast, escalation was not observed during cocaine + nicotine responding, as responding on day 5 of concurrent cocaine + nicotine was not significantly different than responding on day 1 (t(7,24)=0.4390, p>0.9999; Fig. 3C). We observed reduced total responses and response rates for concurrent cocaine + nicotine compared to responding for cocaine alone during the FR1 long access schedule of reinforcement. However the nature of FR schedules of reinforcement does not allow one to determine whether changes are due to increased or decreased reinforcing strength of cocaine + nicotine, as compared to cocaine alone. Reduced response rates could indicate the perception of a higher dose, through titration of drug intake to deliver a desired intake rate, or a lower perceived dose, wherein the animal takes less drug due to reduced reinforcement or motivation.

Fig. 3. Concurrent cocaine + nicotine self-administration decreased responding compared to cocaine alone and prevented escalation of cocaine-taking behaviors.

A) Cocaine + nicotine reversed escalation of responding for cocaine and prevented further escalation. A’) Cocaine + nicotine was self-administered less than cocaine alone. B) Average rate of responding on days 3 through 5 was greater during cocaine alone self-administration, as compared to rate of responding during concurrent cocaine and nicotine self-administration. C) Cocaine alone responding escalated across five days of self-administration, while cocaine + nicotine responding did not escalate. Responding on day 1 of cocaine + nicotine self-administration was equivalent to responding on day 1 of cocaine alone self-administration. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; (#) significant difference between nicotine conditions; ($) significant difference from session 1. N = 7.

3.3. Concurrent nicotine increased responding for cocaine on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement

To determine if the reinforcing strength of concurrent cocaine + nicotine was higher or lower than the reinforcing strength of cocaine alone, we used a PR schedule of reinforcement. During PR responding, the number of lever responses required to obtain the next drug infusion increases systematically, thereby increasing the effort required to obtain an infusion of drug. This gives a measure of motivation, as seen in the total number of infusions earned during the session, and drugs with greater reinforcing strength elicit a greater number of responses. Significant main effects of cocaine dose (F3,93=5.003, p=0.0029), and nicotine condition (F1,75=4.974, p=0.0287) were observed across the PR dose response curve, with no significant interactions (F3,75=0.04040, p=0.7506; Fig. 4). Sidak post hoc analysis did not reveal significant differences between nicotine conditions at any specific cocaine dose. The observed upwards shift in the dose response curve for cocaine + nicotine indicates a greater reinforcing strength for the combination than for cocaine alone.

Fig. 4. Concurrent nicotine increased responding for cocaine on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement.

Concurrent nicotine resulted in increased PR responding across the PR dose response curve, indicating an upward shift in the PR dose response curve when compared to cocaine alone. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; N = 6.

4. Discussion

This study begins to explore the complexities of polysubstance use through a novel examination of concurrent intravenous self-administration of cocaine and nicotine under several behavioral paradigms. While previous preclinical literature has compared responding for cocaine versus nicotine (Manzardo et al., 2002), and has examined the effects of noncontingent nicotine pretreatment on responding for cocaine self-administration, very little research has tested the unique reinforcing effects of contingent concurrent use of these two substances. Our within subject findings, although conducted in a small number of animals, demonstrate that concurrent cocaine + nicotine exposure reduced rates of responding and self-administration behavior relative to responding for cocaine alone under an FR1 long access schedule. As FR responding results were insufficient to indicate whether changes in responding were due to increased or decreased reinforcing strength of the drug combination compared to cocaine alone, we performed PR to assess differences in reinforcing strength. PR dose response curve results showed that combined nicotine + cocaine elicited greater responding than cocaine alone across the different doses, increasing the final number of infusions earned and displaying an upwards shift across the dose response curve. From these findings, we suggest that the combination of cocaine + nicotine has increased reinforcing strength compared to cocaine alone, suggesting that nicotine may enhance the abuse potential of cocaine. It has been shown that response rates on an FR1 schedule begin to decrease with higher doses of cocaine (Koob et al., 2014), which may be due to increased reinforcing strength. This is consistent with findings from the present study, which demonstrate greater reinforcing strength under combined cocaine + nicotine PR self-administration, as compared to cocaine alone PR self-administration.

Clinical CUD research also suggests that nicotine enhances cocaine intake (Budney et al., 1993; Roll et al., 1997; Wiseman and McMillan, 1996) and results in enhanced positive subjective effects of cocaine use when compared to cocaine alone (Wiseman and McMillan, 1998). Pre-clinical findings mirror clinical results, as multiple animal models of self-administration show faster acquisition of cocaine taking and greater responding for cocaine across varied reinforcement schedules when the cocaine self-administration sessions are preceded by noncontingent pretreatment with nicotine (Bechtholt and Mark, 2002; Horger et al., 1992; Mello and Newman, 2011). Despite evidence suggesting that nicotine alone does not produce robust reinforcing effects (Caggiula et al., 2009; Dougherty et al., 1981), it has been shown to facilitate cocaine reinforcement, as repeated pretreatment with nicotine produces leftward shifts in cocaine PR dose response curves (Bechtholt and Mark, 2002). The present study is consistent with the previous literature, and demonstrates an upwards shift in the cocaine + nicotine PR dose response curve, suggesting the facilitation of cocaine reinforcement by nicotine is maintained with prolonged self-administration.

Both cocaine and nicotine increase mesolimbic dopamine levels, although their primary sites of action are different. Nicotine increases extracellular dopamine concentrations through the activation of nAChRs on dopamine cell bodies in the VTA and presynaptic dopamine terminals in the NAc (Wonnacott, 1997). In contrast, cocaine acts primarily to inhibit the DAT, preventing transport of dopamine from the synaptic cleft back into the presynaptic terminal, thereby increasing extracellular dopamine. When cocaine and nicotine are used together, these distinct mechanisms for increasing extracellular dopamine may lead to enhanced reinforcing effects and thereby more substance use in individuals engaging in polysubstance use. In fact, co-administration of cocaine and nicotine has been shown to additively increase extracellular dopamine in the NAc of rats (Zernig et al., 1997), suggesting that co-use of nicotine and cocaine may enhance these substances’ reinforcing effects. While there is some evidence to suggest that cocaine may act as a nAChR antagonist (Acevedo-Rodriguez et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2019), the literature clearly indicates that co-use of cocaine and nicotine results in enhancement of each drug by the other. Therefore, it is clear that nAChRs represent a significant target of interest for future studies aimed at reducing substance use disorders in human populations.

While polysubstance use represents a major public health concern, and cocaine and nicotine are frequently used in combination (John and Wu, 2017), there has been little preclinical research examining co-use of these substances. Previous studies that examined combined self-administration of cocaine and nicotine in non-human primates demonstrated that the addition of nicotine to cocaine self-administration resulted in leftward shifts in PR dose response curves (Freeman and Woolverton, 2009) and increased responding for combined marginally reinforcing doses of cocaine and nicotine under a second-order FR, variable ratio schedule (Mello et al., 2013, 2014; Mello and Newman, 2011). Further, in rodent models, experimenter-delivered mixtures of cocaine and nicotine have been shown to enhance drug-induced locomotor activity and induction of locomotor sensitivity (Barbosa-Mendez and Salazar-Juarez, 2018). As one of the first studies of its kind, the findings from the present rodent self-administration study corroborate these previous findings, as the addition of nicotine to cocaine self-administration resulted in an upwards shift in the PR dose response curve and reductions in long access FR1 responding. Together, these findings suggest that nicotine may enhance the reinforcing strength of cocaine.

Due to the potentially aversive effects of nicotine, it is important to consider nicotine dosing. At high doses, nicotine produces irritation, nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal distress in humans (Fowler and Kenny, 2014; Mishra et al., 2015), and may even result in seizures in both humans and rodents (Iha et al., 2017; Rong et al., 2014; Singer and Janz, 1990). Therefore, it is possible that the dose or amount of nicotine self-administered in the present study was aversive, resulting in decreased responding following its initial introduction during the long-access phase of the protocol. However, it is unlikely that nicotine aversion was the cause of decreased FR1 self-administration responding, as the dose of nicotine selected for this experiment (0.03 mg/kg/inf) has been used extensively in nicotine alone self-administration studies (Caggiula et al., 2001; Corrigall, 1992; Donny et al., 1995; LeSage et al., 2004; Sorge et al., 2009). Additionally, rats have been shown to reliably self-administer nicotine at doses as high as 0.06 mg/kg/inf (Donny et al., 1998; Holmes et al., 2019; Watkins et al., 1999). Further, responding on the PR schedule of reinforcement was greater in the cocaine + nicotine condition; therefore, it is unlikely that the 0.03 mg/kg/inf dose of nicotine used in the present study was aversive.

An important consideration of the experimental design of the present study is drug-associated cues related to cocaine and nicotine self-administration. Previous studies have demonstrated that the presence of drug-associated cues are particularly critical for the development and maintenance of nicotine self-administration behavior (Caggiula et al., 2001; Chaudhri et al., 2007; Donny et al., 1998). In nicotine alone self-administration studies, responding is typically completed during short, limited access sessions of one to two hours (Perkins, 1999), and is highly influenced by environmental and contextual cues, such as visual signals or the separation of housing and drug-associated chambers. This is in contrast to the present study in which rats lived in the custom made self-administration chambers, sessions lasted six hours, and session start was indicated by the extension of the response lever. Further, cocaine + nicotine were administered concurrently through the intravenous catheter following each active lever response. Together, these factors reduced the number of nicotine-associated cues and potentially decreased responding for combined cocaine + nicotine. However, as cocaine + nicotine resulted in greater PR responding than for cocaine alone, it is more likely that the reduced responding observed was due to greater reinforcement strength of the combination of cocaine and nicotine, rather than a lack of nicotine associated cues.

While models of concurrent cocaine + nicotine have greater translational validity when compared to self-administration models of cocaine use alone, there are many differences between preclinical and clinical drug use. First, people who co-use cocaine and nicotine typically initiate substance use with nicotine before transitioning to combined use of cocaine and nicotine. Further, people with CUD, despite using cocaine and nicotine concurrently, likely use these substances through different routes of administration, and do not administer nicotine intravenously. Humans also must choose which substance to direct their behavior towards, and may alternate between use of cocaine and nicotine within a single session of drug use. As the present study was designed to examine the effects of concurrent nicotine to cocaine self-administration responding, the two substances were self-administered simultaneously via the same syringe and intravenous catheter following each active lever response. Therefore, all drug-associated cues, including timeout duration, pump noise, and light illumination, were identical between cocaine alone and cocaine + nicotine conditions, preventing the rats from being able to differentiate between drug conditions by specific drug associated cues. This suggests that observed changes to self-administration responding were likely due to increased potency or reinforcing strength of cocaine self-administered concurrently with nicotine, as compared to cocaine alone. However, as this model does not fully recapitulate the patterns of cocaine and nicotine use that humans with CUD display, future preclinical examinations of polysubstance use in the context of CUD would benefit from polysubstance versus cocaine alone choice procedures to enhance translational validity, and from application of behavioral economics approaches to examine individual differences in consumption and motivation for cocaine + nicotine.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, responding and response rates for concurrent cocaine + nicotine on an FR1 long access schedule were less than for cocaine alone, and concurrent cocaine and nicotine resulted in an upwards shift in a PR dose response curve when compared to cocaine alone. Together, these findings may suggest an increase in the reinforcing strength of cocaine when administered concurrently with nicotine. While in human populations, nicotine may act as a cue for polysubstance use when cocaine is available, our study supports that nicotine itself, without additional environmental cues, may enhance the reinforcing effect of cocaine. These findings are relevant for CUD treatment development and suggest future strategies may need to consider nicotine use in conjunction with CUD, as the data presented here show augmentation of cocaine taking behaviors by nicotine, potentially due to increased cocaine reinforcing strength.

Role of funding source

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) funded this study through Award Numbers F31 DA057815 (MHD), F30 DA048575 (PME), T32 DA041349 (MHD, PME, SRJ), R01 DA048490, R01 DA054694, and P50 DA006634 (SRJ). The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) funded this study though Award Numbers T32 AA007565 (CWW) and U01 AA014091 (KMH, SRJ). Neither NIDA nor NIAAA played any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, the writing of this report, or the decision to submit this report for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict declared.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Monica H. Dawes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Paige M. Estave: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Steven E. Albertson: Methodology. Conner W. Wallace: Writing – review & editing. Katherine M. Holleran: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Sara R. Jones: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A, Zhang L, Zhou F, Gong S, Gu H, De Biasi M, Zhou FM, Dani JA, 2014. Cocaine inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors influences dopamine release. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 6, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold JM, Roberts DCS, 1997. A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 57 (3), 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgaard GL, Gilbert DG, Malpass D, Sugai C, Dillon A, 2010. Nicotine primes attention to competing affective stimuli in the context of salient alternatives. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 18 (1), 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa-Mendez S, Salazar-Juarez A, 2018. Cocaine + nicotine mixture enhances induction and expression of behavioral sensitization in rats. J. Psychiatr. Res 100, 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtholt AJ, Mark GP, 2002. Enhancement of cocaine-seeking behavior by repeated nicotine exposure in rats. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 162 (2), 178–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer AJ 3rd, Mahoney JJ 3rd, Nerumalla CS, Newton TF, De La Garza R 2nd, 2013. The influence of smoking cigarettes on the high and desire for cocaine among active cocaine users. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 106, 132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Higgins ST, Hughes JR, Bickel WK, 1993. Nicotine and caffeine use in cocaine-dependent individuals. J. Subst. Abus. 5 (2), 117–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler K, Forget B, Heishman SJ, Le Foll B, 2021. Significant association of nicotine reinforcement and cue reactivity: a translational study in humans and rats. Behav. Pharm. 32 (2&3), 212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Chaudhri N, Sved AF, 2009. The role of nicotine in smoking: a dual-reinforcement model. Nebr Symp. Motiv 55, 91–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiula AR, Donny EC, White AR, Chaudhri N, Booth S, Gharib MA, Hoffman A, Perkins KA, Sved AF, 2001. Cue dependency of nicotine self-administration and smoking. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 70 (4), 515–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Donny EC, Booth S, Gharib M, Craven L, Palmatier MI, Liu X, Sved AF, 2007. Self-administered and noncontingent nicotine enhance reinforced operant responding in rats: impact of nicotine dose and reinforcement schedule. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 190 (3), 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Gao F, Ma X, Eaton JB, Huang Y, Gao M, Chang Y, Ma Z, Der-Ghazarian T, Neisewander J, Whiteaker P, Wu J, Su Q, 2019. Cocaine Directly Inhibits α6-Containing Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Human SH-EP1 Cells and Mouse VTA DA Neurons. Front. Pharmacol. 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Lindgren S, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ, 2001. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology 41 (1), 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claus ED, Blaine SK, Filbey FM, Mayer AR, Hutchison KE, 2013. Association between nicotine dependence severity, BOLD response to smoking cues, and functional connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology 38 (12), 2363–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Valentino RJ, DuPont RL, 2021. Polysubstance use in the U.S. opioid crisis. Mol. Psychiatry 26 (1), 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigall WA, 1992. A rodent model for nicotine self-administration. In: Boulton AA, Baker GB, Wu PH. (Eds.), Animal Models of Drug Addiction. Humana Press,, Totowa, NJ, pp. 315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Desai RI, Barber DJ, Terry P, 1999. Asymmetric generalization between the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and cocaine. Behav. Pharm. 10 (6–7), 647–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A, 1988. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats, 85 (14), 5274–5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Knopf S, Brown C, 1995. Nicotine self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 122 (4), 390–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Caggiula AR, Mielke MM, Jacobs KS, Rose C, Sved AF, 1998. Acquisition of nicotine self-administration in rats: the effects of dose, feeding schedule, and drug contingency. Psychopharmacology 136 (1), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Chaudhri N, Caggiula AR, Evans-Martin FF, Booth S, Gharib MA, Clements LA, Sved AF, 2003. Operant responding for a visual reinforcer in rats is enhanced by noncontingent nicotine: implications for nicotine self-administration and reinforcement. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 169 (1), 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J, Miller D, Todd G, Kostenbauder HB, 1981. Reinforcing and other behavioral effects of nicotine. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 5 (4), 487–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias GA, Gulick D, Wilkinson DS, Gould TJ, 2010. Nicotine and extinction of fear conditioning. Neuroscience 165 (4), 1063–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler CD, Kenny PJ, 2014. Nicotine aversion: Neurobiological mechanisms and relevance to tobacco dependence vulnerability. Neuropharmacology 76, 533–544. Pt B(0 0). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman KB, Woolverton WL, 2009. Self-administration of cocaine and nicotine mixtures by rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 207 (1), 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes NM, Pan J, Davis A, Panayi MC, Clemens KJ, 2019. Rats choose high doses of nicotine in order to compensate for changes in its price and availability, 24 (5), 849–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horger BA, Giles MK, Schenk S, 1992. Preexposure to amphetamine and nicotine predisposes rats to self-administer a low dose of cocaine. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 107 (2–3), 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iha HA, Kunisawa N, Shimizu S, Tokudome K, Mukai T, Kinboshi M, Ikeda A, Ito H, Serikawa T, Ohno Y, 2017. Nicotine Elicits Convulsive Seizures by Activating Amygdalar Neurons. Front Pharm. 8, 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, Wu LT, 2017. Trends and correlates of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder in the United States from 2011 to 2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 180, 376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalman D, Morissette SB, George TP, 2005. Co-morbidity of smoking in patients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. Am. J. Addict. 14 (2), 106–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karkhanis AN, Beveridge TJ, Blough BE, Jones SR, Ferris MJ, 2016. The individual and combined effects of phenmetrazine and mgluR2/3 agonist LY379268 on the motivation to self-administer cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 166, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedia S, Sell MA, Relyea G, 2007. Mono-versus polydrug abuse patterns among publicly funded clients. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Arends MA, Le Moal M, 2014. Chapter 4 - Psychostimulants. In: Koob GF, Arends MA, Le Moal M. (Eds.), Drugs, Addiction, and the Brain. Academic Press,, San Diego, pp. 93–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y, 2003. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology 168 (1), 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeSage MG, Burroughs D, Dufek M, Keyler DE, Pentel PR, 2004. Reinstatement of nicotine self-administration in rats by presentation of nicotine-paired stimuli, but not nicotine priming. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 79 (3), 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Caggiula AR, Yee SK, Nobuta H, Poland RE, Pechnick RN, 2006. Reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior by drug-associated stimuli after extinction in rats. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 184 (3–4), 417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Elliott AL, Serdarevic M, Leeman RF, Cottler LB, 2019. A latent class analysis of the past-30-day substance use patterns among lifetime cocaine users: Findings from a community sample in North Central Florida. Addict. Behav. Rep. 9, 100170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Roberts DC, Morgan D, 2005. Sensitization of the reinforcing effects of self-administered cocaine in rats: effects of dose and intravenous injection speed. Eur. J. Neurosci. 22 (1), 195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loland CJ, Grånäs C, Javitch JA, Gether U, 2004. Identification of intracellular residues in the dopamine transporter critical for regulation of transporter conformation and cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 279 (5), 3228–3238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzardo AM, Stein L, Belluzzi JD, 2002. Rats prefer cocaine over nicotine in a two-lever self-administration choice test. Brain Res 924 (1), 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Fivel PA, Kohut SJ, 2013. Effects of chronic buspirone treatment on nicotine and concurrent nicotine+cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 38 (7), 1264–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Fivel PA, Kohut SJ, Carroll FI, 2014. Effects of chronic varenicline treatment on nicotine, cocaine, and concurrent nicotine+cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 39 (5), 1222–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Newman JL, 2011. Discriminative and reinforcing stimulus effects of nicotine, cocaine, and cocaine + nicotine combinations in rhesus monkeys. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 19 (3), 203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A, Chaturvedi P, Datta S, Sinukumar S, Joshi P, Garg A, 2015. Harmful effects of nicotine. Indian journal of medical and paediatric oncology: official journal of Indian Society of Medical & Paediatric. Oncology 36 (1), 24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIDA, 2020. How is cocaine addiction treated? https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/cocaine/what-treatments-are-effective-cocaine-abusers. (Accessed July 22 2020).

- Overby PF, Daniels CW, Del Franco A, Goenaga J, Powell GL, Gipson CD, Sanabria F, 2018. Effects of nicotine self-administration on incentive salience in male Sprague Dawley rats. Psychopharmacology 235 (4), 1121–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR, 2007. Self-administration of drugs in animals and humans as a model and an investigative tool. Addiction 102 (12), 1863–1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, 1999. Nicotine self-administration. Nicotine Tob Res 1 Suppl 2, S133–137; discussion S139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich EM, Pagliusi SR, Tessari M, Talabot-Ayer D, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Chiamulera C, 1997. Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science 275 (5296), 83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontieri FE, Tanda G, Orzi F, Chiara GD, 1996. Effects of nicotine on the nucleus accumbens and similarity to those of addictive drugs. Nature 382 (6588), 255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ME, Cragg SJ, 2004. Nicotine amplifies reward-related dopamine signals in striatum. Nat. Neurosci. 7 (6), 583–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC, 1996. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J. Neurosci. Methods 66 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Cone EJ, Kuhar MJ, 1990. Cocaine inhibition of ligand binding at dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters: a structure-activity study. Life Sci. 46 (9), 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ, 1987. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science 237 (4819), 1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Corcoran ME, Fibiger HC, 1977. On the role of ascending catecholaminergic systems in intravenous self-administration of cocaine. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 6 (6), 615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DC, Koob GF, Klonoff P, Fibiger HC, 1980. Extinction and recovery of cocaine self-administration following 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 12 (5), 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, 1996. A comparison of cocaine-dependent cigarette smokers and non-smokers on demographic, drug use and other characteristics. Drug Alcohol Depend. 40 (3), 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roll JM, Higgins ST, Tidey J, 1997. Cocaine use can increase cigarette smoking: evidence from laboratory and naturalistic settings. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 5 (3), 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rong L, Frontera AT Jr., Benbadis SR, 2014. Tobacco smoking, epilepsy, and seizures. Epilepsy Behav.: EB 31, 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Richer I, Arruda N, Vandermeerschen J, Bruneau J, 2013. Patterns of cocaine and opioid co-use and polyroutes of administration among street-based cocaine users in Montreal, Canada. Int J. Drug Policy 24 (2), 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Partridge B, 1999. Cocaine-seeking produced by experimenter-administered drug injections: dose-effect relationships in rats. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 147 (3), 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LP, Kearns DN, Silberberg A, 2018. The effect of nicotine pre-exposure on demand for cocaine and sucrose in male rats. Behav. Pharm. 29 (4), 316–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan J, Javitch JA, Shi L, Weinstein H, 2011. The substrate-driven transition to an inward-facing conformation in the functional mechanism of the dopamine transporter. PLoS One 6 (1), e16350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Badger GJ, Higgins ST, 2003. Acute effects of D-amphetamine on progressive-ratio performance maintained by cigarette smoking and money. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 167 (4), 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J, Janz T, 1990. Apnea and seizures caused by nicotine ingestion. Pediatr. Emerg. care 6 (2), 135–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorge RE, Pierre VJ, Clarke PB, 2009. Facilitation of intravenous nicotine self-administration in rats by a motivationally neutral sensory stimulus. Psychopharmacol. (Berl. ) 207 (2), 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SS, Epping-Jordan MP, Koob GF, Markou A, 1999. Blockade of nicotine self-administration with nicotinic antagonists in rats. Pharm. Biochem Behav. 62 (4), 743–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman EJ, McMillan DE, 1996. Combined use of cocaine with alcohol or cigarettes. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 22 (4), 577–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman EJ, McMillan DE, 1998. Rationale for cigarette smoking and for mentholation preference in cocaine- and nicotine-dependent outpatients. Compr. Psychiatry 39 (6), 358–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonnacott S, 1997. Presynaptic nicotinic ACh receptors. Trends Neurosci. 20 (2), 92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernig G, O’Laughlin IA, Fibiger HC, 1997. Nicotine and heroin augment cocaine-induced dopamine overflow in nucleus accumbens. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 337 (1), 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]