Acute stroke is now a treatable condition that warrants urgent specialist attention. Drug treatment and specialist care both influence survival and recovery. In this article, we consider the optimal approaches to diagnosis and early management.

Stroke, a sudden neurologic deficit of presumed vascular origin, is a clinical syndrome rather than a single disease. A common and devastating condition, it causes death of one third of patients at 6 months (table 1) and leaves another third permanently dependent on the help of others. Each year in the United Kingdom, 110,000 cases of first strokes and 30,000 cases of recurrent strokes occur; 10,000 strokes occur in people younger than 65 years and 60,000 people die of stroke. It is the largest cause of disability, and more than 5% of National Health Service and social services resources are consumed by stroke patients. Correct management relies on rapid diagnosis and treatment, thorough investigation, and rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Death rate (percentage) 30 days, 1 year, and 5 years after different types of stroke

| Stroke type | 30 days | 1 year | 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic stroke | 10 | 23 | 52 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 52 | 62 | 70 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 45 | 48 | 52 |

Conditions requiring referral to a hospital

-

Admit to hospital

- Neurologic deficit lasting 1 hour or more

- Dependent patient—that is, moderate to severe stroke

- Transient ischemic attack lasting 1 hour or more

- More than 1 transient ischemic attack within a week

- Transient ischemic attack while on anticoagulation therapy

- Patient presenting to a hospital

- At request of general practitioner

-

Refer to cerebrovascular clinic

- Independent patient more than 48 hours after stroke; withhold aspirin

- Transient ischemic attack lasting less than 1 hour; give aspirin

Symptoms and signs of stroke

-

Anterior circulation strokes

- Unilateral weakness

- Unilateral sensory loss or inattention

- Isolated dysarthria

- Dysphasia

-

Vision:

- Homonymous hemianopia

- Monocular blindness

- Visual inattention

-

Posterior circulation strokes

- Isolated homonymous hemianopia

- Diplopia and disconjugate movement of eyes

- Nausea and vomiting

- Incoordination and unsteadiness

- Unilateral or bilateral weakness and/or sensory loss

-

Nonspecific signs

- Dysphagia

- Incontinence

- Loss of consciousness

Clinical examination after stroke

Conscious level

Neurologic signs

Blood pressure

Heart rate and rhythm

Heart murmurs

Peripheral pulses

Systemic signs of infection or neoplasm

ASSESSING THE PATIENT

Patients should be assessed at a hospital immediately after a stroke. They may need to go straight to the hospital rather than wait to see their general practitioner because treatments such as thrombolysis must be administered within as little as 3 hours after stroke. Ambulance crews can be trained to apply simple screening questions to identify patients who are likely having a stroke.

Stroke is a clinical diagnosis, but brain imaging is required to distinguish ischemia from primary intracerebral hemorrhage. The pattern of neurologic signs, including evidence of motor, sensory, or cortical dysfunction and hemianopia, can be used to diagnose certain clinical subtypes and thus to predict prognosis (table 2). Other signs also relate to outcome and may help identify the cause. If neurologic symptoms resolve within 24 hours, the traditional diagnostic term is “transient ischemic attack” rather than stroke. However, not all transient ischemic attacks are genuinely ischemic; many are associated with permanent cerebral damage. A better term therefore, is “ministroke.”

Table 2.

Characteristics of subtypes of stroke

| Characteristic and prognosis | Lacunar | Partial anterior circulation | Total anterior circulation | Posterior circulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs | Motor or sensory only | 2 of following: motor or sensory; cortical; hemianopia | All of: motor or sensory; cortical; hemianopia | Hemianopia; brain stem; cerebellar |

| Dead at 1 year, % | 10 | 20 | 60 | 20 |

| Dependent at 1 year, % | 25 | 30 | 35 | 20 |

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

For practical purposes, there are 2 types of stroke after subarachnoid hemorrhage has been excluded. Ischemia accounts for 85% of presentations and primary hemorrhage for 15%. Hemorrhage causes direct neuronal injury, and the pressure effect causes adjacent ischemia. Primary ischemia results from atherothrombotic occlusion or an embolism. The usual sources of embolism are the left atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation or the left ventricle in patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure.

Vessel occlusion arises from atherosclerosis, typically in the internal carotid artery just above the carotid bifurcation or from small vessel disease deep within the brain. Ischemia causes direct injury from lack of oxygenation and nutritional support and sets up a cascade of neurochemical events that lead to spreading damage. The ischemia may be reversible if reperfusion is obtained quickly (now proved in clinical trials), and the chemical injury may be interrupted by various neuroprotective drugs (unproved in humans).

EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT

Within the first hours after the onset of cerebral ischemia, part of the brain is under threat of death. The infarct core may be densely ischemic and will inevitably die, but tissue with a compromised blood supply is also balanced on a knife edge between death and recovery. At this stage, oxygenation and hemodynamic and metabolic factors are crucial. The emergency management of stroke requires medical stabilization and assessment of factors that may lead to complications (such as swallowing and hydration); thrombolysis may be considered (discussed later). An acute stroke unit concentrates patients, health care staff, resources, and expertise into 1 area, and such units may be associated with a better outcome.

INVESTIGATIONS

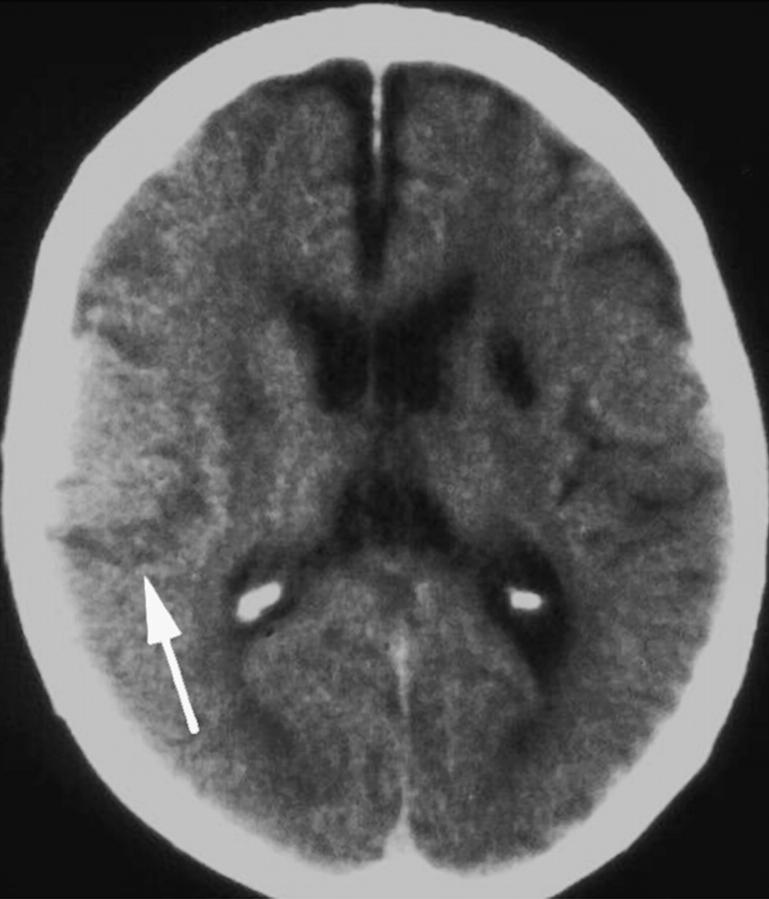

Patients with acute stroke should have computed tomography of the brain to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic stroke (figures 1 and 2). This separation is vital because subsequent investigations and treatment differ for the 2 types. Neuroimaging will also identify conditions that mimic stroke (table 3) and can help predict outcome. Ideally, imaging will be performed soon after admission. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain may eventually replace computed tomography because it not only identifies stroke anatomy but can also assess blood flow and perfusion in the brain, detect whether lesions are new or old, and identify carotid artery stenosis (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan showing ischemic stroke

Figure 2.

Computed tomographic scan showing hemorrhagic stroke

Table 3.

Conditions that mimic stroke

| Diagnosis | Diagnostic features |

|---|---|

| Decompensation of previous stroke | Evidence of infection such as urinary or respiratory tract; metabolic disturbance |

| Cerebral neoplasm (primary or secondary) | Less abrupt onset; primary tumor or secondary to, for example, lung or breast cancer |

| Subdural hematoma | Recent head injury |

| Epileptic seizure | Possible previous episodes |

| Traumatic brain injury | History of trauma |

| Migraine | Less abrupt onset; followed by headache; younger patients |

| Multiple sclerosis | Less abrupt onset; possible previous episodes |

| Cerebral abscess | Infection |

Figure 3.

Magnetic resonance angiogram showing middle cerebral artery occlusion

The extent to which the cause of the stroke should be investigated depends on several factors, including the likely degree of recovery, the presence of obvious risk factors, and the age of the patient. Younger patients are more likely to have an identifiable cause such as an inflammatory or clotting disorder that may require specific treatment. Although investigations should be restricted to tests that will inform clinical management, guidelines can be used to determine which investigations are needed after stroke.

Investigation of stroke

-

All patients

- Computed tomography (or magnetic resonance imaging)

- Electrocardiography

- Chest radiography

- Complete blood cell count

- Clotting screen

- Electrolyte and creatinine concentrations

-

Subgroups

- Carotid duplex scanning

- Echocardiography

- Thrombophilia screen

- Immunology screen

- Serologic test for syphilis

- Cerebral angiography (rarely)

Acute drug therapies for ischemic stroke

-

Aspirin

- Most patients

- Heparin (unfractionated or low molecular weight)

-

Prophylactic

- Previous venous thromboembolism

- Morbid obesity

-

Therapeutic

- Carotid artery dissection

- Embolic, recurrent transient ischemic attacks

Complications of stroke

Hyperglycemia

Hypertension

Fever

Infarct extension or rebleeding

Cerebral edema, herniation, coning

Aspiration

Pneumonia

Urinary tract infection

Cardiac dysrhythmia

Recurrence

Deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism

SWALLOWING AND FEEDING

Dysphagia affects 35% of stroke patients. It is often unrecognized after mild stroke and is associated with a poor outcome, partly because it predisposes to aspiration and pneumonia and partly because of the nutritional deficit. The presence of a gag reflex is a poor guide to safe swallowing, and a formal assessment by trained staff is essential. Fluids are more difficult to swallow than semisolids. Dysphagic patients should be fed through a nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic feeding tube until it is safe to resume oral food and fluids. Most dysphagic patients will not need enteral feeding beyond a few weeks. However, when and how optimally to feed dysphagic patients remain to be determined.

ACUTE INTERVENTION

Firm evidence from 2 large trials has shown that a regimen of aspirin (160-300 mg daily by mouth, nasogastric tube, or rectum) started within 48 hours of the onset of acute ischemic stroke reduces the risk of subsequent disability and death. However, the effect of aspirin is small (number needed to treat [NNT] = 77) and is principally mediated through reducing the risk of early reinfarction. Neuroimaging is strongly recommended before starting the aspirin regimen. A large trial of the use of unfractionated heparin in stroke patients found that heparin did not improve outcome, even in patients with presumed embolic stroke. Recently, low-molecular-weight heparin has proved ineffective in individual large trials and meta-analysis. Heparin may still be useful in certain groups of patients.

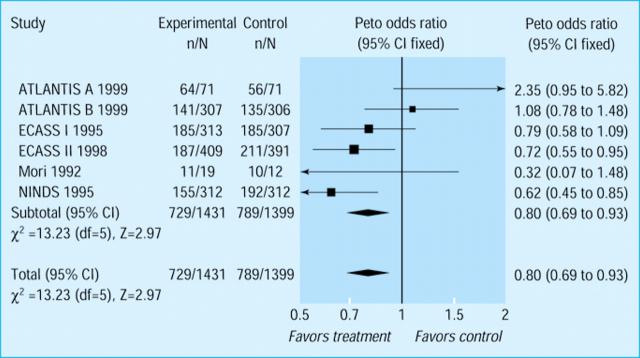

Thrombolysis with alteplase recombinant within 3 hours of the onset of stroke significantly increases the chance of a nearly complete recovery (NNT = 7) when administered by specialists (figure 4). Treatment up to 6 hours after a stroke has been less effective in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (estimated NNT = 12). Thrombolysis is currently licensed for use in stroke only in North America, and concerns remain about its safety if used indiscriminately.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis shows that thrombolysis reduces combined disability and death from stroke

Neuroprotectant drugs (which may protect neurons from ischemia) have to date shown no benefit in ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, although several trials are still in progress.

Patients with a large cerebellar infarct or hemorrhage should be referred for immediate neurosurgical evaluation to facilitate evacuation of the clot or infarct or shunting for acute hydrocephalus, if required. Anticoagulant therapy should be reversed in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage.

COMPLICATIONS OF STROKE

Stroke may be complicated by several conditions that can alter outcome adversely. Hyperglycemia, fever, and hypertension are each associated with a poor prognosis. In the absence of trial evidence, increased glucose concentrations should be normalized and paracetamol [acetaminophen] given for fever (figure 5). In contrast, hypertension should not be treated for the first week because some antihypertensive drugs (notably calcium channel blockers) seem to worsen outcome, possibly be reducing regional cerebral blood flow. Large ischemic strokes are often complicated by edema, swelling, and herniation, leading to death; no proven treatment is available for these complications.

Figure 5.

Stroke patient receiving rehabilitation therapy

Venous thromboembolic disease (deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism) develops in half of immobile patients unless preventive measures are taken. Although compression stockings reduce the risk of deep venous thrombosis in other groups of highrisk patients, this has not been confirmed in patients with stroke. A combination of stockings, early mobilization, adequate hydration, and aspirin is considered good practice in patients with ischemic stroke. Early mobilization may also reduce the risk of pressure sores and respiratory and urinary tract infections. When possible, the use of urinary catheters should be avoided to minimize the risk of infection.

REHABILITATION

The principal aims of rehabilitation are to restore function and reduce the effect of the stroke on patients and their care givers. Rehabilitation should start early during recovery with assessment and mobilization while the patient is in the acute stroke unit. Once patients are medically stable, they should be transferred to a stroke rehabilitation unit if further rehabilitation is required. Formal rehabilitation in a stroke unit is associated with reduced incidences of disability and death (NNT = 12) and a shorter stay in the hospital. Optimal care is multidisciplinary: physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, dieticians, psychologists, and social workers all have a role.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Secondary prevention (apart from blood pressure control) should start shortly after admission. All patients should be offered lifestyle guidance, including advice to stop smoking, reduce saturated fat and salt consumption and alcohol intake, lose weight, and increase exercise. Aspirin therapy started for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke should be continued indefinitely for secondary prevention. The use of alternative or additional antithrombotic drugs—dipyridamole, clopidrogrel bisulfate, and warfarin sodium—carotid endarterectomy, and management of hypertension and hyperlipidemia after stroke is discussed elsewhere (BMJ 2000;320:991-994).

THE FUTURE

Stroke management is now supported by solid evidence, but many questions remain unanswered. Whenever possible, patients should be given the opportunity to enroll in randomized trials of acute interventions, rehabilitation, or secondary prevention.

Further reading

Bath PMW. The medical management of stroke. Int J Clin Pract 1997;51:504-510.

Lees KR. If I had a stroke....Lancet 1998;352(suppl 3):28-30.

Stroke Audit Package. London: Royal College of Physicians; 1994.

Stroke Units Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative systematic review of the randomised trials of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care after stroke. BMJ 1997;314:1151-1159.

Competing interests: None declared This clinical review was published in BMJ 2000;320:920-923

The magnetic resonance image was provided by Professor Alan Moody, University of Nottingham. The data on thrombolysis were provided by Dr Joanna Wardlaw, University of Edinburgh.