The Mae Tao medical school on the Thai-Burma border

“I can do episiotomies, suture wounds and deliver babies now...but the hardest part is that I need to learn more....If you stop learning, then you stop living.” Tah Bo, junior medic

Imagine learning to practice medicine in 1 year, in a language you only partially understand. Picture returning to your jungle refugee camp, or perhaps the front line, where patients with high fevers and rigors look to you for a cure.

These are the lives of Burmese refugee medics. I spent 3 weeks with them in October of 1999 during an elective at the Mae Tao clinic on the border between Thailand and Burma. The creation of this clinic, a de facto medical school, was spurred by Burma's political turmoil.

In the summer of 1998, 60 students arrived at the Mae Tao clinic for intensive medical training. They came by foot, truck, or plane from the 9 refugees camps scattered up and down the Thai-Burma border. A few trekked for days from their villages in Burma just to be trained by Dr Cynthia Maung, who is widely known as a selfless physician dedicated to helping her people.

Most of these journeys were sponsored by nongovernment organizations, which are assisting with developing an infrastructure and other activities in the camps, or by the Karen National Union, a political group battling with the current Burmese military junta for control of the Karen state in Burma. A few students were sponsored by individual benefactors working in the camps; others arrived on their own, unannounced. Dr Cynthia warmly welcomed them all. For the 6 years that the medic training program has existed, she has never charged tuition.

These young medics grew up in conditions that would shock westerners. Their families were among the hundreds of thousands forced from their homes in Burma by oppressive military rule. They moved to border refugee camps, many of which have been attacked or burned at least once. Everyone here knows someone who has been beaten, raped, or killed. And now the students have chosen a 1-year crash course in medicine in order to better help their fellow refugees.

When she first established the clinic in 1989, Dr Cynthia treated patients with war wounds and malaria with the assistance of a small staff. Some university students who fled Burma in the late 1980s and early 1990s came to help the refugee patients at the clinic and to learn from Dr Cynthia. At that time, medical instruction was largely informal, and the students learned on the job.

The first class of medics graduated in 1994 with less than 40 students. “Each year, the number [of students] has increased, as has the quality of the students attending,” said senior medic Htat Aung, a former university student who teaches public health.

An Australian teacher working in Mae Ra Moo camp sponsored 20-year-old Htoo Paw to make the 7-hour trip to the clinic in the back of a truck. She began classes on the day of her arrival. “It was a new experience,” she said in her quiet English. “I met people from other places...we had different culture problems, but we tried to negotiate with each other.”

Aside from their different religious backgrounds, many of the students are of Karen ancestry, a minority group in Burma, while others are Burmese. This diversity is a source of conflict. The Karen are indigenous to Southeast Asia, and by most historical accounts, they are the original settlers of where Burma stands today. Centuries ago, these traditionally peaceful, devout farmers were driven from their homes or enslaved by the Burman (ethnic Burmese), who won the feudal war for control of the area. In the 20th century, the Burmese government has repeatedly denied the Karen request for a self-determined state. The Karen united with other ethnic minority groups in Burma to form the National Democratic Front in opposition to the ruling government. Even though the Burmese military government persecutes the ethnic minorities and economically disadvantaged Burman alike, unspoken tensions still exist between the Karen and Burmese students.

Classes are taught in Burmese, which makes it difficult for the Karen who have their own language and who learned Burmese in high school as a second language. “There is still a problem with the different languages,” said Dr Cynthia. “Next year we will have some more people who speak Karen and can help tutor students at night.”

After graduating, the students' lives may never cross paths again. Some, like Htoo Paw, leave within weeks to fulfill their obligations to their sponsors by returning to the camps. Others, like Tah Bo, remain behind to gain practical experience in the clinic before leaving. In the camps, some medics will work under a volunteer doctor's supervision, while others will be virtually alone in their practice.

Some students will be sent to the front lines in the jungle to help Karen National Union soldiers. Those who come to the clinic without a sponsor are allowed to stay for 2 to 3 years. The newly graduated medics can treat a range of conditions, such as endemic infections, trauma, and malnutrition. They can also deliver babies. The medicine they practice is far from perfect, but in this war-torn area, brief medical training is better than none.

As for the future of the program, many questions remain. Should there be a limit on the number of medics trained per year? If so, is an entrance examination necessary to screen for minimal intellectual requirements? And should students be able to get specialized training in certain subjects? In answer to this last question, Dr Cynthia replied: “We teach primary care medicine here. As patients develop more severe health problems, like HIV, tuberculosis, and severe malaria, the specialized training needs to increase. Also, the demand from nongovernment organizations to train medics for the camps continues to grow.”

The conflict in Burma is likely to continue indefinitely, creating the need for new generations of medics who will be prepared to help their fellow refugees.

Figure 1.

Tah Bo administers oral polio vaccine at a nearby refugee camp

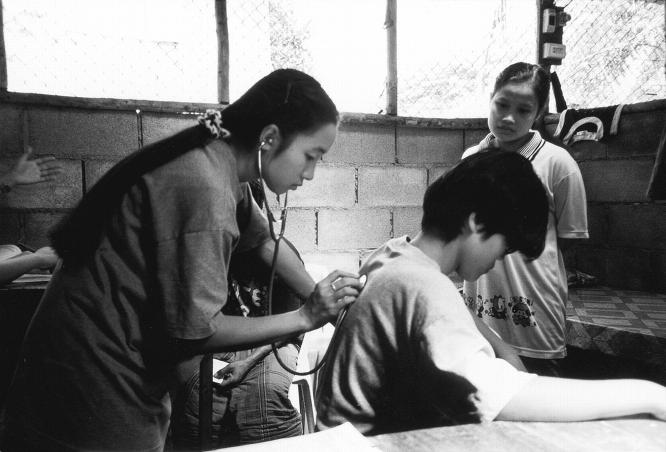

Figure 2.

Htoo Paw examines a patient while a new medic watches and learns

For more information about Dr Meung's clinic, or to make a donation, contact: The Allende Program in Social Medicine, 520 Washington Blvd #380, Marina del Rey, CA 90292.