1. Introduction

Fractures of the distal radius are one of the most common causes of emergency room visits at 1.5 %, and they constitute the most common type of fractures reported.1 They represent a large population group that affects the patients beyond the medical cost, performance and attendance in schools, work hours lost, dependence for daily activities and lasting disability. Children are at risk for fall related injuries sustained in the playground which constitutes 80 % and boys having a higher incidence of fractures than girls.2 Distal radius fractures account for 18 % of all fractures sustained by the elderly age(>65 years), and with an increasing elderly population, the cost of both healthcare systems and social structure is set to increase.3 Young adults (19–49 years) have lower incidence of distal radius fracture, however, the high energy injury related to motor vehicle accidents and sport related injuries, represents a higher effect on their life being young, healthy and independent prior to injury.4 We describe following certain steps to achieve reliable outcomes.

2. Materials and methodology

Patients operated by a single team from 2019 to 2022 (4 yours).

-

●

Total 48 patients

-

●

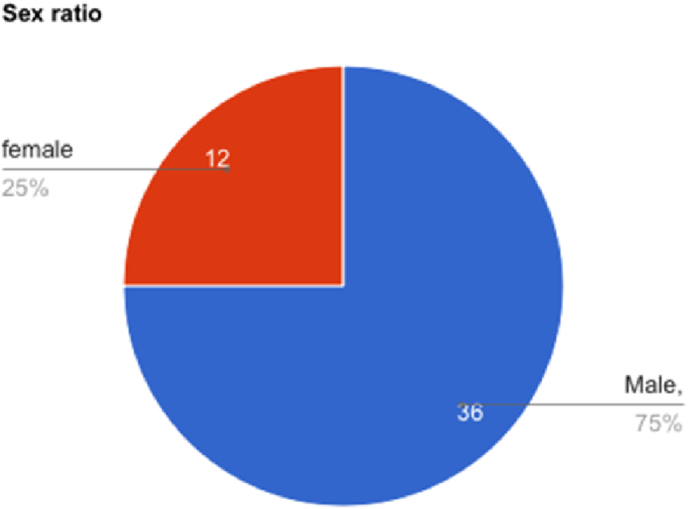

36 male patients. 12 female patients (Fig. 1). Youngest 27 years and oldest 82 years.

-

●

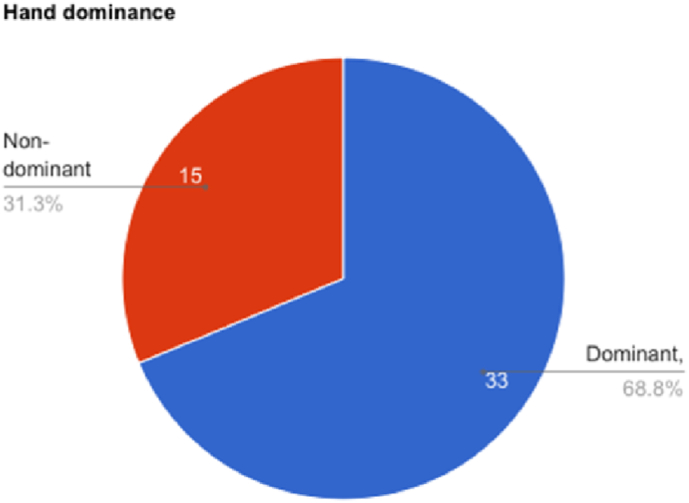

Dominant hand in 33 patients and non-dominant in 15 patients (Fig. 2).

-

●

Preoperative imaging included X-ray and computed tomography in 47 patients. Only X-ray in one patient

-

●Fracture patterns were

-

○33 patients with comminuted intraarticular fracture with very distal volar rim fracture, 11 dorsal barton, 2 patients with failure of fixation, 1 burst fracture pattern,1 metaphyseal fracture (Fig. 3)

-

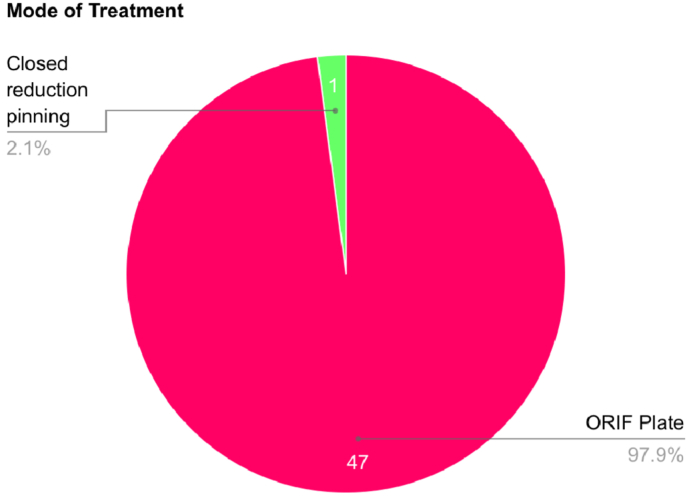

○47 patients underwent open reduction internal fixation with plate, one patient underwent closed reduction K-wire (Fig. 4)

-

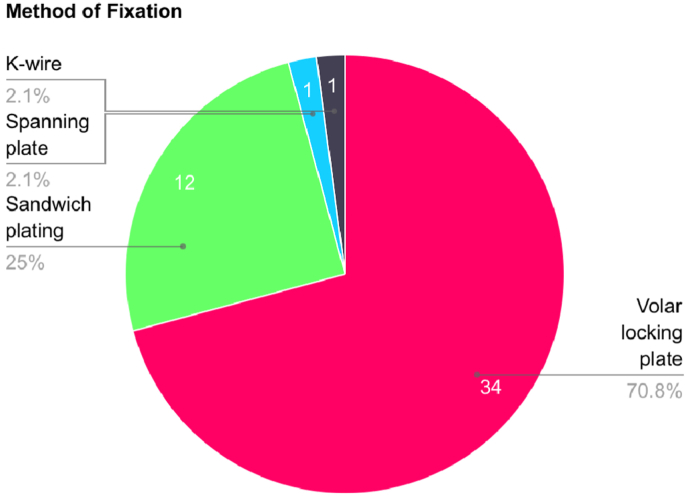

○34 patients underwent volar locking plate alone, 12 underwent sandwich plating and one dorsal spanning plate and one closed reduction K-wire respectively (Fig. 5)

-

○All the patients had isolated distal radius fractures

-

○Two patients had bilateral distal radius fractures

-

○

Fig. 1.

Sex ratio.

Fig. 2.

Hand dominance.

Fig. 3.

Fracture pattern.

Fig. 4.

Treatment method.

Fig. 5.

Mode of fixation.

2.1. Does classification affect outcome?

The purpose of any classification system is to allow communication, guide intervention or management and predict outcomes, also they have to be simple, easy to remember and have reproducibility(intra-observer) and reliability(reliability).5,6 Classification systems are most useful when they facilitate rapid and succinct communication between doctors, determine a treatment protocol, guide recovery and predict prognosis.

There are 15 described classifications for distal radius as referenced by the International Distal Radius Fracture Study Group. Shehoyvich7 evaluated Gartland & Werley, Older, Frykman, Melone, AO/ASIF, Mayo, Fernandez and the Universal classification systems for classifying distal radius fractures for historical, clinical and research purposes, subjected them to kappa (κ) statistic for reliability and reproducibility. They concluded that none of the evaluated systems are robust to undergo statistical scrutiny and fail at being unreliable, irreproducible, complicated and abstract. They also summarise that the spectrum of injuries affecting the distal radius makes it difficult. Which follows the studies by different authors8, 9, 10, 11 s Further trainee surgeons spend their effort memorising the different systems rather than understanding the mechanics of the fracture and their relevance in management and prognosis.12,13 An unhelpful system will only further miscommunication, limit their clinical use and eventually become a tool only for theoretical knowledge. Ilyas and Jupiter studied various classification systems and indication for surgery, they inferred that although many classifications exist, they have helped identify different aspects of distal radius fracture and its outcome.14

In our practice, we have found the “Patient-accident-fracture” (PAF) classification of distal radius fracture15,16 and the criteria for stability of distal radius fracture as described by Lafontaine17,18 as reliable tools for determining treatment and predicting outcome.

The following are criteria for open reduction internal fixation with plating.

-

1.

A volar displaced fracture,

-

2.

Volar or dorsal comminution,

-

3.

Subchondral void,

-

4.

Die-punch fracture/Free osteochondral fragment

-

5.

Incarcerated fragment

-

6.

Dorsal angulation >20°

-

7.

Intraarticular step >3 mm, also

-

8.

Relative loss of height of radius

Recently Chung and Chung19 concluded that.

-

1.Radiographic parameters

-

a.Absence of volar cortical hook

-

b.Dorsal fracture

-

c.Communition are predictive of instability

-

a.

-

2.Patient factors

-

a.Age

-

b.Functional demand

-

c.Preference

-

a.

-

3.

Die-punch fracture requires dorsal plate/dorsal spanning plate

-

4.

Intra-articular fracture with >2 mm step or gap would benefit from arthroscopic assisted fixation

We find that, after fracture characteristic, the age to be a factor in determining treatment. Where again the PAF classification determnining the patients demand, hand dominance.

2.2. What do the patient and the surgeon want? Does surgeon preference determine outcome?

2.2.1. What does the patient want

We find that patients report to us in three ways following a distal radius fracture.

-

1.

They come following a referral by a colleague or by another patient treated by us (majority)

-

2.

They are referred from the emergency department

-

3.

Walk-in to the clinic (least)

Patients and their relatives want to know the treatment and the urgency they present having been told that they have a fracture (broken bone) that needs immediate surgery.

1. They are informed that a closed fracture is not an emergency, and that splintage, limb elevation, anti-edema medications and imaging are needed before they are wheeled into the operating room.

2. Any superficial soft tissue injuries need thorough wash and.

Following this, a doctor is asked if surgery is definitely needed or can they opt for non-operative management. A systematic review found that there is no significant difference in functional parameters following non-surgical treatment in initial management between surgical and non-surgical methods.20 And Ochen found that in a systematic analysis patients who underwent surgical management had better DASH score and grip strength compared to non-operative patients.21 It is determined that 40 % patients who choose non-operative management, even after being informed that there is a 1 in 3 chance of displacement.22

2.2.2. What does the surgeon want & surgeon preference

Saliban found that plate was the dominant method of choice for fellowship trained hand surgeons.23,24 Childs describes that there is an association between hand surgery fellowship training and the choice of intervention for distal radius fracture.25 Over the last decade, there has not been any change in the percentage of surgeons working in facilities that have 24/7 emergency hand call or the percentage of surgeons paid to take hand calls. However, there is a decrease in surgeons taking obligatory hand call from 70 % in 2010 to 50 % in 2019, and 34 % not taking hand calls in 2019 compared to 18 % in 2010. The main barrier being lifestyle considerations.26 Among orthopedic surgeons in the United States, 34 % take hand calls excluding replantation, 28 % do not take hand calls, 60 % take <6 calls per month, 49 % are financially incentivised to take calls, 51 % report they have protected time aside from elective practice and 10 % have a dedicated operating room for cases after call. Of them only 46 % are satisfied with the call schedule.27 In 2019, in the United States, it was found that state level variations in density of specialist hand surgeon were independent and significantly associated with median per capita income and with density of fellowship, leading to disparity in access to emergency hand trauma care in lower per capita income states.28 Lans29 determined that hand and pediatric surgeons performed more off-hour work compared to their colleagues. An online survey conducted among plastic surgery residents, 185 respondents tested, 48.5 % reported moderate-high burnout,of these 25 % were above the 75th percentile of overall burnout score,30 however it should be noted that unlike as mentioned in the article, trainees are never in fixed 8 h duties. Another online survey conducted among 330 practicing plastic surgeons reported 8.2 % burn out rates.31

A patient will choose surgical intervention if a shared decision making process is initiated between the doctor and patient. A doctor will choose a surgical option based on the training in the speciality.

2.3. How does imaging affect outcome?

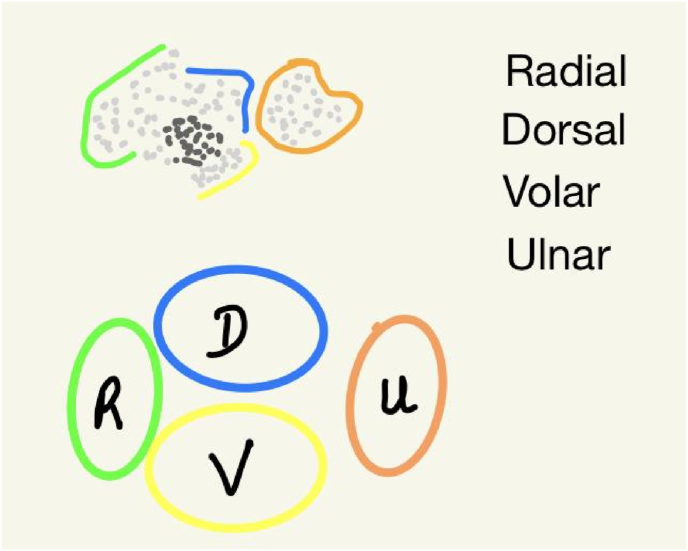

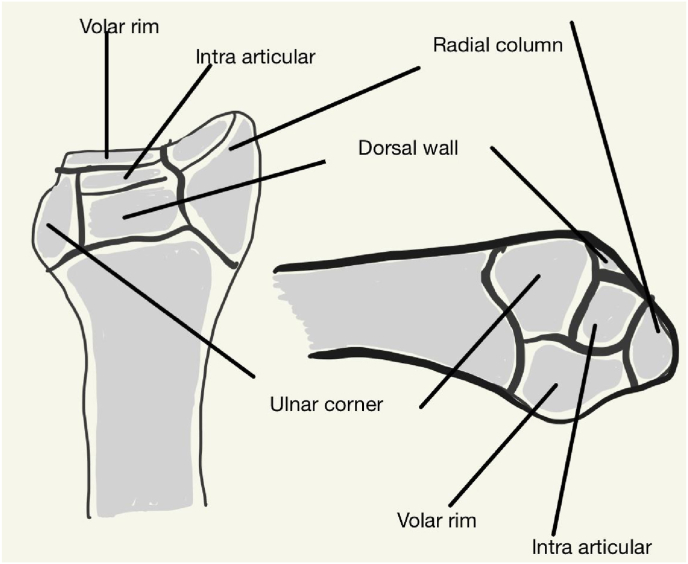

A thorough understanding of radiographic anatomy of the distal radius facilitates accurate assessment.32 Radiography includes standard X-ray wrist true posteroanterior (PA) view and 10° lateral view.33 In a true PA view, that patients sits on a low stool with the shoulder abducted 90°, elbow flexed 90° and wrist in neutral position. In the true lateral view the patient sits high and elbow is elevated 10° with the degree depending on fracture characteristics. Here it should be noted that the Central Reference Point (Fig. 6), which is midway between the volar and dorsal ulnar corners to eliminate variations due to dorsal angulation, this point helps in the measurement of radial inclination and radial height. The “tear-drop” sign is the U-shaped outline of the volar rim of the lunate facet, seen on the 10° lateral X-ray. The anteroposterior distance is between the apex of the dorsal and volar rim. Computed tomography(CT) is the investigation of choice to determine the morphological characteristics of the distal radius fracture. It can assist evaluation when there is a plaster cast,34 in the presence of an impacted intraarticular fragment,35 determining extension of articular extension of fracture and congruity. It has been shown to be specific in determining the fracture pattern compared to an plain radiograph.36,37 Following the fragment concept,38 it has been shown that this may not be specific to determine the dorsal medial fragment.39 The three column40 concept facilitated the understanding of fixation of distal radius fracture, the four corner concept (Fig. 7) helps predict fracture pattern,41 the ligamentous attachments to the distal radius also determine the fracture characteristics is determined with CT imaging.42 Magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) is used to assess early soft tissue injuries.43 Associated injuries of tendon44 (extensor pollicis longus45), of scapholunate and lunotriquetral ligament with interspace widening >4 mm, volar tilt of scaphoid and dorsal or lunar tilt of lunate46 and triangular fibrocartilage complex47

As noted, various imaging modalities add on to the knowledge of fracture pattern and associated soft tissue injuries, it is to be seen how many patients undergo preoperative CT and how many fail due to failure of fixation due to limited study of fracture characteristics.

Fig. 6.

Central reference point.

Fig. 7.

Four column concept.

2.4. How does exposure of the fracture affect outcome?

Internervous planes are followed to approach the forearm bones. Choice of approach depends on the injury pattern and the level of exposure.48 The Henry approach exposes the plance between the median and radial nerves. However, Orbay approach,49 or the Extended flexor carpi radialis(FCR) approach, exposed the distal radius volarly approximately 3.3 cm of the width and provides 79 % exposure of the radius and ends 4.7 cm distal to the radiocapitellar joint if extended proximally.50 Our approach follows the Orbay method.

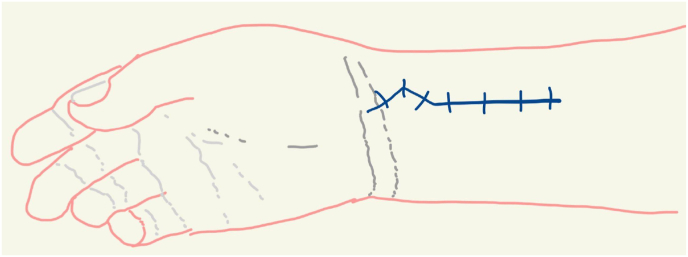

2.4.1. Superficial exposure

(Fig. 8) The skin incision is marked dostally with two flexion creases over the distal pole of scaphoid and trapezial ridge, an 8 cm incision is made along the FCR tendon with the distal most portion marked as a chevron with the base radially, the apex of the chevron is distal to both flexion creases of the wrist. The branches of palmar cutaneous branch and superficial radial nerves are safely retracted away.

Fig. 8.

Marking of incision.

2.4.2. FCR tendon sheath and mid level exposure

(Fig. 9) The superficial tendon sheath is released distally where the superficial radial artery, which is identified and ligated, it is then opened distally along with the Fibres of Mercer51 over its attachment into the trapezium to allow retracting the tendon. The subsheath is opened on the floor by incising along its entire length, this separates the FCR from the flexor pollicis longus(FPL). The FPL is identified by moving the thumb, blunt dissection of the FPL and the flexor tendons along the median nerve with gentle finger sweeps from radial to ulnar side exposes few perforators from the radial artery which are cauterised. This exposes the space of Parona on the pronator quadratus(PQ).

Fig. 9.

Exposure of flexor carpi radialis.

2.4.3. Radial septum and triangle52

The lateral wall of the distal aspect of the flexor compartment is continuous with the lateral aspect of the radius and radiocarpal ligaments, proximally the septum is a thin intermuscluar membrane from the lateral edge of the radius to the brachioradialis, distally it is formed from the lateral wall of the carpal bursa and ends where the FCR converges with the carpal bones. The distal part of the radial septum is a three-dimensional, which is narrow proximally and wide distally. It has a roof(FCR sheath), a floor(volar carpal ligaments), the apex is proximal at the volar radial tuberosity, the base is broad and extends from that scaphoid tuberosity to the lateral wall of the carpal tunnel, which is the medial wall, the radial artery forms the lateral wall of the triangle.

The radial artery is retracted laterally to identify the first extensor compartment, this exposes the brachioradialis. Once the extensor tendons and the radial artery are safely retracted with a bone spike. The brachioradialis is divided close to the radius on the underside of the belly of the tendon as it is traced distally.

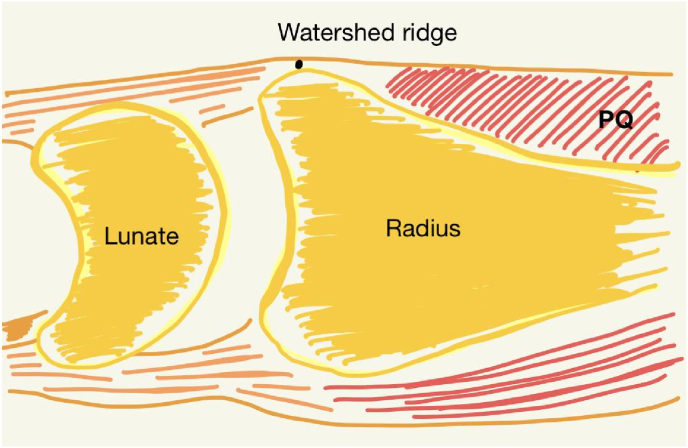

2.4.4. Exposure of radius

The two elevations on the volar rim of the lunate fossa and the radial tubercle, the interfossa sulcus between them. The watershed53,54 line is more of a ridge (Fig. 10) is the distal edge of the PQ and runs along the sulcus. The PQ muscle is proximal to the line. Betweem these two is a thick periosteum that attaches to the volar radius just proximal to the origin of the volar radiocarpal ligaments, called the transitional fibrous zone(TFZ). The PQ is released by sharp dissection from the TFZ in a proximal & medial direction. Care to be taken to avoid the stripping of ulnar border of the radius where branches of the anterior interosseous artery traverse. This exposes the fracture except the intraarticulat fragments. A capsulotomy on the volar wrist capsule opens an intraarticular extended window55 which exposes the articular surface of the radius, we raise an ulnar based adipofascial flap involving the volar wrist capsule which includes the fascia on the TMZ distally and the tissue between the long and short radiolunate ligaments(communication Dr. Sanj Kakar, Mayo Clinic, Rochester). This allows direct visualisation of intraarticular fragments. The distal fragment is elevated and intrafocal elevation is done to expose a subchondral void which takes in bone graft. Fracture is elevated with traction and manipulation of fracture fragments. After fixation of the radius, the PQ is sutured in forearm protonation and the FCR subsheath is sutured. Visualisiing the distal fracture fragments and reducing them prevents progressive loss of reduction of initial reduction due to dorsal collapse, loss of radial height and loss ot lunate facet reduction.56

Exposure of the radius by releasing volar distal radius, raising the adipofascial capsular flap, releasing the brachioradialis to negate the proximal migration and supination of the radial styloid fragment, visualisation of the intraarticular fragments57allows almost 360° view of the distal radius. The aphorism “one cannot operate that which once cannot see” holds true.

Fig. 10.

Watershed line.

2.5. Release of brachioradialis and fixing the radial column

The brachioradialis is a superficial muscle of the forearm, it acts to flex the elbow but also to pronosupination of the forearm. Originates from the proximal ⅔ of lateral supracondylar ridge of humerus and distally into the lateral surface of the styloid process of the radius. Variations of the muscle exist with an insertion of the tendon into the third metacarpal.58 The insertion of the tendon lies 17 mm proximal to the tip of the radial styloid and extends 15 mm proximally and is 11 mm wide. The whole length of the tendon is firmly attached to the antebrachial fascia. The tendon is bordered consistently by septa of first extensor compartment, forming a tunnel-like thick structure.59 Biomechanical studies conclude that release of the tendon during fixation of distal radius fracture, the elbow flexion torque reduced to 95 %, 90 % and 86 % at a release distance of 27, 46, and 52 mm, respectively. It remains >80 % of original value even at a distance of 7 cm. This shows that the overall elbow flexion torque reduces less that 5 %.60

2.6. Fixation of ‘keystone’ fragment and failure of fixation

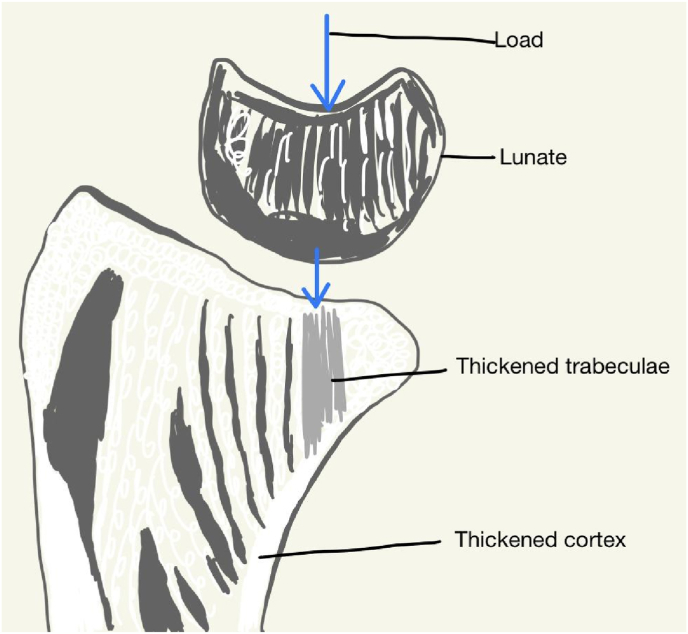

The volar ulnar fragment accounts for 4–11 % of distal radius fracture.61 Fracture pattern varies from volar rim fracture to an isolated fragment. The volar ulnar fragment is key due to its ligamentous attachment to the ulna and the radiocarpal ligaments and forms the radioulnar joint and the radiocarpal joints. Due to these characteristics, there is a higher incidence of carpal instability, failure of fixation and revision surgery62

Skeletal architecture of the volar ulnar corner: sagittal images of the lunate facet show thickened trabecular columns in line with the volar cortex.63 This shows that high loads on the volar rim require stable rigid fixation to avoid failure. As Wolf's law states, regions of greater loading produce higher density of bone. The volar ulnar cortex and the thickened trabecular form the radial calcar (Fig. 11). The wrist has a “Shenton's line” between the radius and ulna (Fig. 12). Fracture of the radial calcar, the radial shaft translates in an ulnar direction. Secondary collapse of the fragment is common due to the osteoligamentous concept, referred to sleeper lesions. The force from the initial volar ulnar corner can propagate along the volar rim resulting in an occult volar ligament injuries, due to the articular fragments and ligament attachments.42 They can be detected only when the wrist is mobilised or loaded. This lesion should be suspected in high energy injury with significant edema and hyperemia, an MRI detects the fracture pattern64 these factors lead to the volar ulnar corner named the “critical corner”, “keystone fragment”. The factors that determine failure of fixation of the volar ulnar fragment are separate scaphoid and lunate facet fragment, >5 mm depth of lunate subsidence and <15 mm available for fixation.65 A standard volar locking plate may not be adequate to reduce the volar ulnar fragment, it should be preferable to identify the complexity of the injury and plan adequate fixation methods.66 Many methods have been described to fix this fragment,67,68 we use the Synthes variable angle 2.4 mm rim plate69

Due to the difficulty in identifying the pattern of injury, preparing a plan of management needs adequate preoperative imaging and should be rcommended it is treated a trained upper extremity surgeon.

Fig. 11.

Radial calcar.

Fig. 12.

Shenton's line.

2.7. Dorsal & radial styloid fractures (fragment specific fixation)

Since the description of the fragment specific classification by Medoff (Fig. 13), fixation devices are included that can combine or augment the reduction of all the fragments (see Fig. 14).

-

a)

Radial styloid: they occur due to compression or shear forces and rarely due to avulsion force due to extreme ulnar deviation of wrist. This fracture can be an isolated fracture70 or be part of distal radius fracture. The indication for plating the radial styloid for buttress are proximal migration and comminution, it is used to correct coronal alignment and a volar locking plate for sagittal alignment. We use one or two Kirschner wires to fix a radial styloid fracture and use a radial buttress plate if comminution using the same volar exposure to fix the plate. This technique assists anatomic reduction and provide stable fixation.71

-

b)

Dorsal ulnar fragment & dorsal wall: A dorsal approach is used to fix due to the attachment of the TFCC. the incision is on longitudinal line from the 3rd metacarpal to the Lister's tubercle, full thickness skin flaps are raised, subcutaneous tissue is dissected by finger sweeps to expose the extensor retinaculum. The EPL is exteriorised by releasing the roof of the extensor tendon. An incision on the retinaculum at the level of the space between the 3rd & 4th compartment and elevation of the periosteal flap exposes the fracture fragments. The tubercle is erased and an appropriate fixation device is used to reduce the fragment in buttress plating.

-

c)

Dorsal spanning plate: the use of distraction plate for severely comminuted distal radius fracture.72 The plate spans from the third metacarpal and bypasses the fracture area. The use of the implant shows good functional, radiological and patient-rated scores.73 Multiple reviews show that this method achieves consistent results for a select group of patients.74,75

A low threshold should be adopted to use fragment specific fixation to achieve anatomic and stable reduction, bone grafts should be used to augment subchondral support76, 77, 78

Fig. 13.

Medoff classification of fracture pattern.

Fig. 14.

Sandwich plating.

2.8. Soong criteria and tendon complications

Soong described 3 grades to identify chances of flexor tendon rupture where grade 0-implant does not extend to the watershed line, grade 1- implant at the line but proximal to volar rim and grade 2- at the volar rim,79 there is a positive correlation between higher soong grade and rates of implant removal doe to tendinopathies.80 The watershed line best defined as a ridge and not a line. The ridge can be palpated on the raised volar tubercle.

If a fracture has to be reduced distal to the watershed line, the standard volar locking plate should be deferred and an appropriate device should be used to achieve reduction.

2.9. Bone graft

Although many studies have evaluated the use of bone grafts81 to determine if cancellous autograft versus autograft should be used to comminuted fracture to fill void,82 and bone graft substitutes.83, 84, 85 A low threshold for the use of bone graft should be followed. Two questions have to be answered to determine the use of bone graft or substitutes.

-

a)

Whether to use bone grafts in all dorsal or volar comminution? The quality of bone, size of the defect should determine the use of bone graft

-

b)

If a bone graft is needed, which is the ideal material? In our practice, we use a iliac crest bone graft with outer or inner table or both, if a structural graft is required. If only cancellous graft is required, a trap dorr flap is elevated from the cortex, which is closed after graft harvest.

3. Associated distal radioulnar Joint(DRUJ) injuries

The outcome of management of distal radius fracture is also affected by the congruity of the DRUJ. The DRUJ should be evaluated after satisfactory restoration of radial height and sagittal and coronal tilt. the stability of DRUJ depends on 1)restoration of mechanical integrity of sigmoid notch & 2) continuity of dorsal & volar radioulnar components of TFCC and their attachment onto the fovea.9 If the DRUJ is unstable and there is an unsatisfactory reduction, all attempts should be made to restore alignment. If residual instability is present after anatomical reduction, the limb is immobilised in above elbow slab in full supination of forearm for 6 weeks to aid in healing of TFCC.

4. Discussion

As the knowledge of the fracture biomechanics improves, the fixation methods to achieve reduction has expanded. Earlier, a study that evaluated the preference of surgical management showed increase in open reduction from 42 % in 1999 to 81 % in 2007,86 a consensus on the use of implant is yet to be determnined.87 There is a higher chance that a hand surgery trained surgeon will choose surgical intervention and obtain a preoperative CT scan and determine plan of management.88,89 The other factors that determine mode of treatment are presence of comorbidities, functional demand, practice setting of the surgeon.90 It should be noted that closed distal radius fractures can be managed initially with plaster splint, hand elevation antiedema measures, if there are superficial soft tissue injuries they can be managed with thorough wash on the first visit.91

5. Summary

| PAF Classification aids in determining management | Proper imaging techniques - Neutral PA and true lateral radiograph and preoperative CT imaging |

|---|---|

| Shared decision making between patient and surgeon | “What the eye cannot see cannot be operated upon” - Adequate exposure |

| Ideally treated by a trained hand surgeon | Fragment specific fixation with appropriate plate |

| Low threshold for using a bone graft | Evalaute DRUJ after anatomical reduction of distal radius |

Case Example 1: Young male, non-dominant hand, fall while riding a bike, pre-operative CT showed incarcerated central depressed fracture with burst type fracture of distal radius, patient underwent ORIF with sandwich plating.

Case Example 2: Young male, dominant hand, presented with edematous, tender, stiff hand with deformity. Operated 6 weeks prior for same injury. Noticed deformity on removal of plaster and painful movement on physiotherapy. Pre-operative X-ray & CT revealed failed implant with screw in radiocarpal joint. Underwent Diagnostic arthroscopy to evaluate cartilage status, implant removal, ORIF with sandwich plating of volar, radial and dorsal columns with iliac crest bone graft.

Middle aged male, dominant hand, fall on outstretched hand, pre-operative imaging showed volar rim fracture. ORIF done with Synthes Rim plate to buttress the distal fragment.

References

- 1.Melton L.J., Iii, Amadio P.C., Crowson C.S., O'Fallon W.M. Long-term trends in the incidence of distal forearm fractures. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(4):341–348. doi: 10.1007/s001980050073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ryan L.M., Teach S.J., Searcy K., et al. Epidemiology of pediatric forearm fractures in Washington, DC. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2010;69(4):S200–S205. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181f1e837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baron J.A., Karagas M., Barrett J., et al. Basic epidemiology of fractures of the upper and lower limb among Americans over 65 Years of age. Epidemiology. 1996;7(6):612–618. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brogren E., Petranek M., Atroshi I. Incidence and characteristics of distal radius fractures in a southern Swedish region. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2007;8(1):48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burstein A.H. Fracture classification systems: do they work and are they useful? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75(12):1743–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kural C., Sungur I., Kaya I., Ugras A., Ertürk A., Cetinus E. Evaluation of the reliability of classification systems used for distal radius fractures. Orthopedics. 2010;33(11):1–5. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100924-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shehovych A., Salar O., Meyer C., Ford D.J. Adult distal radius fractures classification systems: essential clinical knowledge or abstract memory testing? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2016;98(8):525–531. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2016.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreder H.J., Hanel D.P., McKee M., Jupiter J., McGillivary G., Swiontkowski M.F. Consistency of AO fracture classification for the distal radius. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(5):726–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jupiter J.B., Fernandez D.L. Comparative classification for fractures of the distal end of the radius. J Hand Surg. 1997;22(4):563–571. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kucuk L. Reliability and reproducibility of classifications for distal radius fractures. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2013;47(3):153–157. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2013.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ploegmakers J.J.W., Mader K., Pennig D., Verheyen C.C.P.M. Four distal radial fracture classification systems tested amongst a large panel of Dutch trauma surgeons. Injury. 2007;38(11):1268–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen D.J., Blair W.F., Stevers C.M., Adams B.D., El-Khouri G.Y., Brandser E.A. Classification of distal radius fractures: an analysis of interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility. J Hand Surg. 1996;21(4):574–582. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(96)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulders M.A.M., Rikli D., Goslings J.C., Schep N.W.L. Classification and treatment of distal radius fractures: a survey among orthopaedic trauma surgeons and residents. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017;43(2):239–248. doi: 10.1007/s00068-016-0635-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ilyas A.M., Jupiter J.B. Distal radius fractures—classification of treatment and indications for surgery. Orthop Clin N Am. 2007;38(2):167–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herzberg G., Galissard T., Burnier M. Patient–accident–fracture (PAF) classification of acute distal radius fractures in adults. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2018;28(8):1459–1463. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzberg G., Izem Y., Al Saati M., Plotard F. “PAF” analysis of acute distal radius fractures in adults. Preliminary results. Chir Main. 2010;29(4):231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafontaine M., Hardy D., Delince Ph. Stability assessment of distal radius fractures. Injury. 1989;20(4):208–210. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(89)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lafontaine M., Delince P., Hardy D., Simons M. [Instability of fractures of the lower end of the radius: apropos of a series of 167 cases] Acta Orthop Belg. 1989;55(2):203–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung SR, Chung KC. Recognizing and treating unique distal radius fracture patterns that are prone to displacement. Hand Clin. Published online March 2023:S0749071223000069. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2023.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.He B., Tian X., Ji G., Han A. Comparison of outcomes between nonsurgical and surgical treatment of distal radius fracture: a systematic review update and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140(8):1143–1153. doi: 10.1007/s00402-020-03487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochen Y., Peek J., Van Der Velde D., et al. Operative vs nonoperative treatment of distal radius fractures in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blough C., Harvey Kuschner S. Distal radius fracture: what does the patient want? Open J Orthoped. 2022;12(6):288–296. doi: 10.4236/ojo.2022.126028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salibian A.A., Bruckman K.C., Bekisz J.M., Mirrer J., Thanik V.D., Hacquebord J.H. Management of unstable distal radius fractures: a survey of hand surgeons. J Wrist Surg. 2019;8(4):335–343. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1675792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salibian A.A., Bruckman K.C., Bekisz J.M., Mirrer J., Thanik V.D., Hacquebord J.H. Abstract: management preferences in treatment of unstable distal radius fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg - Glob Open. 2018;6:59–60. doi: 10.1097/01.GOX.0000546795.43640.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Childs S., Mann T., Dahl J., et al. Differences in the treatment of distal radius fractures by hand fellowship trained surgeons: a study of abos candidate data. J Hand Surg. 2017;42(2):e91–e97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eberlin K.R., Payne D.E.S., McCollam S.M., Levin L.S., Friedrich J.B. Hand trauma network in the United States: ASSH member perspective over the last decade. J Hand Surg. 2021;46(8):645–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douleh D.G., Ipaktchi K., Lauder A. Hand call practices and satisfaction: survey results from hand surgeons in the United States. J Hand Surg. 2022;47(11) doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2021.08.021. 1120.e1-1120.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rios-Diaz A.J., Metcalfe D., Singh M., et al. Inequalities in specialist hand surgeon distribution across the United States. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(5):1516–1522. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lans A., Janssen S.J., Ring D. Off-hour surgery among orthopedic subspecialties at an urban, quaternary-care, level 1 trauma center. J Hand Surg. 2016;41(12):1153–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panse N., Panse S., Ravi S., Mankar H., Karanjkar A., Sahasrabudhe P. Burnout among plastic surgery residents in India: an observational study. Indian J Plast Surg Off Publ Assoc Plast Surg India. 2020;53(3):387–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karanjkar A., Panse N., Panse S., Sahasrabudhe P. Indian perspective of burnout among plastic surgeons. Indian J Plast Surg Off Publ Assoc Plast Surg India. 2023;56(2):153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1759727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann F.A., Wilson A.J., Gilula L.A. Radiographic evaluation of the wrist: what does the hand surgeon want to know? Radiology. 1992;184(1):15–24. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1609073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medoff R.J. Essential radiographic evaluation for distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2005;21(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metz V.M., Gilula L.A. Imaging techniques for distal radius fractures and related injuries. Orthop Clin N Am. 1993;24(2):217–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onishi T., Omokawa S., Shimizu T., Kawamura K., Nagashima M., Tanaka Y. Impacted intraarticular fragments of distal radius fractures: a radiographic characterization and analysis of reliability and diagnostic accuracy. J Orthop Sci. 2022;27(2):384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2020.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arora S., Grover S.B., Batra S., Sharma V.K. Comparative evaluation of postreduction intra-articular distal radial fractures by radiographs and multidetector computed tomography. J Bone Jt Surg-Am. 2010;92(15):2523–2532. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeffrey Cole R., Bindra R.R., Evanoff B.A., Gilula L.A., Yamaguchi K., Gelberman R.H. Radiographic evaluation of osseous displacement following intra-articular fractures of the distal radius: reliability of plain radiography versus computed tomography. J Hand Surg. 1997;22(5):792–800. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melone C.P. Articular fractures of the distal radius. Orthop Clin N Am. 1984;15(2):217–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S., Zhang Y.Q., Wang G.H., Li K., Wang J., Ni M. Melone's concept revisited in comminuted distal radius fractures: the three-dimensional CT mapping. J Orthop Surg. 2020;15(1):222. doi: 10.1186/s13018-020-01739-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rikli D.A., Regazzoni P. Fractures of the distal end of the radius treated by internal fixation and early function. A preliminary report of 20 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(4):588–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brink P., Rikli D. Four-corner concept: CT-based assessment of fracture patterns in distal radius. J Wrist Surg. 2016;5(2):147–151. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1570462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mandziak D.G., Watts A.C., Bain G.I. Ligament contribution to patterns of articular fractures of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. 2011;36(10):1621–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozin S.H., Wood M.B. Early soft-tissue complications after fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Jt Surg. 1993;75(1):144–153. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199301000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steinbach L.S., Smith D.K. MRI of the wrist. Clin Imag. 2000;24(5):298–322. doi: 10.1016/S0899-7071(00)00218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar A., Kelly C.P. Extensor pollicis longus entrapment after Smith's fracture. Injury. 2003;34(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(02)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cerezal L., Piñal F.D., Abascal F., García-Valtuille R., Pereda T., Canga A. Imaging findings in ulnar-sided wrist impaction syndromes. Radiographics. 2002;22(1):105–121. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.1.g02ja01105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Potter H.G., Asnis-Ernberg L., Weiland A.J., Hotchkiss R.N., Peterson M.G.E., McCormack R.R. The utility of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of the triangular fibrocartilage complex of the wrist. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(11):1675–1684. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199711000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klausmeyer M.A., Mudgal C. Exposure of the forearm and distal radius. Hand Clin. 2014;30(4):427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orbay J.L., Badia A., Indriago I.R., et al. The extended flexor carpi radialis approach: a new perspective for the distal radius fracture. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2001;5(4):204–211. doi: 10.1097/00130911-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jockel C.R., Zlotolow D.A., Butler R.B., Becker E.H. Extensile surgical exposures of the radius: a comparative anatomic study. J Hand Surg. 2013;38(4):745–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yeager K., Heifner J., Rubio F., Gray R., Orbay J., Mercer D. Flexor carpi radialis tendon insertion onto the trapezial ridge: an anatomic description. J Hand Surg Glob Online. 2023;5(1):55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsg.2022.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orbay J.L., Gray R., Vernon L.L., Sandilands S.M., Martin A.R., Vignolo S.M. The EFCR approach and the radial septum—understanding the anatomy and improving volar exposure for distal radius fractures: imagine what you could do with an extra inch. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2016;20(4):155–160. doi: 10.1097/BTH.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bergsma M., Doornberg J.N., Hendrickx L., et al. Interpretations of the term “watershed line” used as reference for volar plating. J Wrist Surg. 2020;9(3):268–274. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bergsma M., Doornberg J.N., Borghorst A., Kernkamp W.A., Jaarsma R.L., Bain G.I. The watershed line of the distal radius: cadaveric and imaging study of anatomical landmarks. J Wrist Surg. 2020;9(1):44–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kamal R.N., Ostergaard P.J., Shapiro L.M. The volar intra-articular extended window approach for intra-articular distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg. 2023;48(5):516.e1–516.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berglund L.M., Messer T.M. Complications of volar plate fixation for managing distal radius fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(6):369–377. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orbay J.L. The treatment of unstable distal radius fractures with volar fixation. Hand Surg. 2000;5(2):103–112. doi: 10.1142/S0218810400000223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sañudo J.R., Young R.C., Abrahams P. Brachioradialis muscle inserting on the third metacarpal. J Anat. 1996;188(Pt 3):733–734. Pt 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koh S., Andersen C.R., Buford W.L., Patterson R.M., Viegas S.F. Anatomy of the distal brachioradialis and its potential relationship to distal radius fracture. J Hand Surg. 2006;31(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tirrell T.F., Franko O.I., Bhola S., Hentzen E.R., Abrams R.A., Lieber R.L. Functional consequence of distal brachioradialis tendon release: a biomechanical study. J Hand Surg. 2013;38(5):920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marcano A., Taormina D.P., Karia R., Paksima N., Posner M., Egol K.A. Displaced intra-articular fractures involving the volar rim of the distal radius. J Hand Surg. 2015;40(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Eardley-Harris N., MacLean S.B.M., Jaarsma R., Clarnette J., Bain G.I. Volar marginal rim fractures of the distal radius have a higher rate of associated carpal injuries—a comparative cohort study. J Wrist Surg. 2022;11(3):195–202. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Giunta R., Löwer N., Wilhelm K., Keirse R., Rock C., Müller-Gerbl M. Altered patterns of subchondral bone mineralization in kienböck’s disease. J Hand Surg. 1997;22(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chiri W., MacLean S.B., Clarnette J., Eardley-Harris N., White J., Bain G.I. Anatomical and clinical concepts in distal radius volar ulnar corner fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2022;11(3):238–249. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-1748674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beck J.D., Harness N.G., Spencer H.T. Volar Plate fixation failure for volar shearing distal radius fractures with small lunate facet fragments. J Hand Surg. 2014;39(4):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harness N.G., Jupiter J.B., Orbay J.L., Raskin K.B., Fernandez D.L. Loss of fixation of the volar lunate facet fragment in fractures of the distal part of the radius. J Bone Jt Surg-Am. 2004;86(9):1900–1908. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O'Shaughnessy M., Shin A., Kakar S. Stabilization of volar ulnar rim fractures of the distal radius: current techniques and review of the literature. J Wrist Surg. 2016;5(2):113–119. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1579549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heifner J.J., Orbay J.L. Assessment and management of acute volar rim fractures. J Wrist Surg. 2022;11(3):214–218. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1732338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spiteri M., Roberts D., Ng W., Matthews J., Power D. Distal radius volar rim plate: technical and radiographic considerations. World J Orthoped. 2017;8(7):567–573. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v8.i7.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andreotti M., Tonon F., Caruso G., Massari L., Riva M.A. The “chauffeur fracture”: historical origins of an often-forgotten eponym. Handb Neuropsychol N. 2020;15(2):252–254. doi: 10.1177/1558944718792650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacobi M., Wahl P., Kohut G. Repositioning and stabilization of the radial styloid process in comminuted fractures of the distal radius using a single approach: the radio-volar double plating technique. J Orthop Surg. 2010;5(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-5-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruch D.S., Ginn T.A., Yang C.C., Smith B.P., Rushing J., Hanel D.P. Use of a distraction plate for distal radial fractures with metaphyseal and diaphyseal comminution. J Bone Jt Surg. 2005;87(5):945–954. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liechti R., Babst R., Hug U., et al. The spanning plate as an internal fixator in complex distal radius fractures: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48(3):2369–2377. doi: 10.1007/s00068-021-01738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Perlus R., Doyon J., Henry P. The use of dorsal distraction plating for severely comminuted distal radius fractures: a review and comparison to volar plate fixation. Injury. 2019;50:S50–S55. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2019.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fares A.B., Childs B.R., Polmear M.M., Clark D.M., Nesti L.J., Dunn J.C. Dorsal bridge plate for distal radius fractures: a systematic review. J Hand Surg. 2021;46(7):627.e1–627.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Geissler W., Clark S. Fragment-specific fixation for fractures of the distal radius. J Wrist Surg. 2016;5(1):22–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hozack B.A., Tosti R.J. Fragment-specific fixation in distal radius fractures. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2019;12(2):190–197. doi: 10.1007/s12178-019-09538-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim J., Yun Y.H., Kim D. The effect of displaced dorsal rim fragment in a distal radius fracture. J Wrist Surg. 2016;5(1):31–35. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Soong M., Earp B.E., Bishop G., Leung A., Blazar P. Volar locking plate implant prominence and flexor tendon rupture. J Bone Jt Surg-Am. 2011;93(4):328–335. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Selles C.A., Reerds S.T.H., Roukema G., van der Vlies K.H., Cleffken B.I., Schep N.W.L. Relationship between plate removal and Soong grading following surgery for fractured distal radius. J Hand Surg Eur. 2018;43(2):137–141. doi: 10.1177/1753193417726636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tosti R., Ilyas A.M. The role of bone grafting in distal radius fractures. J Hand Surg. 2010;35(12):2082–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rajan G.P., Fornaro J., Trentz O., Zellweger R. Cancellous allograft versus autologous bone grafting for repair of comminuted distal radius fractures: a prospective, randomized trial. J Trauma Inj Infect Crit Care. 2006;60(6):1322–1329. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195977.18035.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Handoll H.H., Watts A.C. vol. 2010. Cochrane Bone, Joint and Muscle Trauma Group; 2008. Bone Grafts and Bone Substitutes for Treating Distal Radial Fractures in Adults. (Cochrane Database Syst Rev). 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Disseldorp D.J.G., Poeze M., Hannemann P.F.W., Brink P.R.G. Is bone grafting necessary in the treatment of malunited distal radius fractures? J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(3):207–213. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1558831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ozer K., Chung K.C. The use of bone grafts and substitutes in the treatment of distal radius fractures. Hand Clin. 2012;28(2):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koval K.J., Harrast J.J., Anglen J.O., Weinstein J.N. Fractures of the distal part of the radius: the evolution of practice over time. Whereʼs the evidence? J Bone Jt Surg-Am. 2008;90(9):1855–1861. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koval K., Haidukewych G.J., Service B., Zirgibel B.J. Controversies in the management of distal radius fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(9):566–575. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-22-09-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Doermann A., Gupta D.K., Wright D.J., et al. Distal radius fracture management: surgeon factors markedly influence decision making. JAAOS Glob Res Rev. 2023;7(3) doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-23-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kyriakedes J.C., Crijns T.J., Teunis T., Ring D., Bafus B.T. Science of variation group. International survey: factors associated with operative treatment of distal radius fractures and implications for the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons' appropriate use criteria. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33(10):e394–e402. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goodman A.D., Blood T.D., Benavent K.A., Earp B.E., Akelman E., Blazar P.E. Implicit and explicit factors that influence surgeons' decision-making for distal radius fractures in older patients. J Hand Surg. 2022;47(8):719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ahmad F., Neral M., Hoyen H., Simcock X., Malone K. Does time to operative intervention of distal radius fractures influence outcomes? Hand. 2022;17(1_suppl):135S–139S. doi: 10.1177/15589447211072219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]