Abstract

Background

Intercultural communication between physicians and patients is a prominent challenge faced by health sectors. This integrative review aims to explore and summarize the current literature examining the cultural factors impacting the communication experience of patients and physicians in healthcare settings and provide an evidence-based solution.

Methods

We used Whittemore and Knafl's (2005) approach to conduct this integrated review of the literature. Primary research studies meeting the search criteria were accessed from Medline/PubMed, Embassy, CINAHL, PsycInfo, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Review. We included studies published in English from 2008 to 2022. A total of 1731 studies were identified, of which 34 articles were included in this review.

Results

The findings revealed a difference in physicians' communicative behaviour when encountering patients from different cultural backgrounds compared to encounters with patients from the same cultural background. When communicating with patients from different cultural backgrounds, physicians were found to be authoritarian, biomedical-focused, and not involve patients in decision-making. Patients' behaviours during consultations and experience and perception of quality of care in intercultural consultations were varied and inconclusive. Often patients were found to exaggerate respect for physicians, feel uncomfortable with the direct communication style of physicians, have a less proactive attitude, demonstrate low health literacy, and feel shy. These behaviours were attributed to language differences, differences in perception of disease, perception of health communication, prejudice, assumptions, training experience of physicians, and time allocated for consultations. Further, ineffective communication in intercultural consultations was found to impact patient satisfaction, medical adherence, continuity of care, physician's job satisfaction, and ability to diagnose correctly.

Conclusions

Effective communication plays a significant role in patient and physician satisfaction. Health policymakers must formulate appropriate policies that encourage expatriate physicians to develop intercultural competencies to enhance intercultural communication, improve satisfaction, quality decision-making, correct diagnosis, and enhance public health.

Keywords: Integrative literature review, Health care Delivery, Database, Patients, physicians

1. Introduction

The literature review explores previous research that has examined intercultural communication (ICC) between patients and physicians. It adds weight to the justification for the study by focusing more specifically on patient and physician experiences. Effective physician-patient communication results in numerous positive outcomes for both physicians and patients. Effective physician-patient communication has been directly linked to patient satisfaction [[1], [2], [3]]. Satisfied patients are less likely to file complaints against the institution or physician and serve as an indicator of high-quality patient care [4,5]. The effect of satisfied patients on physicians includes increased job satisfaction and fewer work-related issues such as stress and burnout [6,7]. Effective communication fosters a good physician-patient relationship, facilitates a proper exchange of information, endorses patient behaviour toward a treatment-adherence, and consequently improves health outcomes [[8], [9], [10], [11]]. Good consultation communication facilitates an accurate diagnosis by sharing pertinent information in concerning their health problems, and adhering to the physician's advice prescribed treatment [2,3,12,13]. Compelling evidence links effective physician-patient communication to therapeutic and physiological outcomes, such as reduced blood pressure and blood sugar [9,14]. One of the challenging areas within healthcare communication is the physician's ability to communicate with patients from culturally different backgrounds [15].

Intercultural communication (ICC) means studying how people from different cultures communicate and how communication style compares to others from different cultural backgrounds. Such studies usually compare the communication styles of two different nations according to specific criteria such as directness and openness. In other words, ICC in this study refers to what happens when two people (physician and patient) from different cultural backgrounds meet or come into direct contact. For example, Matusitz and Spear [16]compared the communication styles of patients from the US and three Asian countries (Pakistan, Thailand, and Japan). They found that patients from the US tended to communicate more clearly, explicitly, and directly with their physicians than their Asian counterparts. Another recent example of a cross-cultural communication study found that Turkish patients tended to be indirect and inexplicit compared with Dutch patients when they communicated with their physicians; for instance, when physicians posed questions, the Turkish patients tended to tell anecdotes to illustrate their answers rather than answering directly [17].

ICC is a potential source of low-quality communication, with more misunderstandings and potentially negatively impacting the quality of care [18]. Moreover, several studies suggest that intercultural medical consultations display more miscommunication, misunderstanding, dissatisfaction, and poorer patient compliance than intracultural medical consultations [[19], [20], [21], [22]].

Three literature reviews were found that specifically addressed ICC in medical consultations. A review of observational studies conducted by Schouten and Meeuwesen [23] aimed to identify the impact of cultural differences on both physician and patient behaviours and found that most of the studies they reviewed did not link communication behaviour to culture or cultural variations in doctor-patient communication to outcomes. The authors identified five key predictors of culture-related communication problems: cultural differences in explanatory models of health and illness, differences in cultural values, cultural differences in patient preferences for doctor-patient relationships, racist/perceptual biases, and linguistic barriers.

A systematic review by Rocque and Leanza [24] synthesized qualitative studies exploring patients' experiences communicating with a primary care physician. The authors reported negative experiences, positive experiences, and outcomes of communication. Negative experiences included being treated with disrespect, experiencing pressure due to time constraints, and feeling helpless due to the dominance of bio-medical culture in the medical encounter. Positive experiences were linked to physicians' relational and technical skills and approaches to care. For ethnic minorities, language barriers, discrimination, differing values, and acculturation were negative influences. Ethnic majorities also reported differing values and discrimination communication impacted outcomes. The findings of this review are limited by the fact that more than half of the studies reviewed did not explore cultural aspects relating to this experience. Paternotte, van Dulmen [25] conducted a realist review of factors influencing ICC, focusing on communication between physicians of dominant ethnicity and patients of minor ethnicity. Their findings are similar to Roque and Leanza in that they found that intercultural communication is impacted by language, cultural and social differences, and doctors' assumptions. They identified that objectives, core skills, and specific skills were important in determining outcomes of patient-physician interaction. No review of ICC during medical consultations has been conducted since 2015. Reviewing the empirical studies identified key theme areas like those reported in previous literature reviews. These were physicians' reported communication behaviour and experiences, patients' reported behaviours and experiences, intercultural consultations reported outcomes, and physicians’ mitigating skills behaviours.

This review examines research into cultural factors influencing the communication experience of patients and physicians during medical consultations. The review moves from an exploratory focus revealing the factors that influence ICC to an explanatory focus on how those factors affect the process [26]. Intercultural communication occurs between two interlocutors from different cultural backgrounds [27]. Communication can be challenging even with participants from the same cultural group; however, intercultural communication is perceived to be more challenging. Physician-patient encounters are a critical and key component in the healthcare process [28,29]. The purpose of medical communication is to facilitate information exchange and shared decision-making [30]. However, in the intercultural context, inherent differences between physicians and patients might hamper the exchange of crucial information. The multidimensional components of culture, such as values, perspectives, and beliefs about illness, are intensified by communication difficulties in the ICC medical encounter [31,32]. Salim et al. identified new advancements essential in solving communication issues among patients and physicians [33]. These are para verbal communication, i.e., pace of voice and tone of voice; using a soft tone and maintaining proper pace could help both better understand each other. In addition, eye contact, appropriate facial expressions, attentiveness listening, and prognosis of disease play a significant role in effective communication.

Integrative reviews summarize and report reliable, valid, and accurate findings. Reviews help healthcare providers to keep themselves updated with recent advancements in the field. These reviews also help policymakers judge risks and take benefits from the findings reported systematically to help physicians and patients and intervene if necessary. Reviews are also important because sometimes the primary information about the subject matter is not adequately reported, thus reducing their usefulness. Further, it helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the subject matter. Through review, the researchers can collect and combine information and data to answer specific research questions. In the field of patient-physician communication, an updated and recent integrative review is missing so far, and it is essential to identify the main factors responsible for patient-physician communication. Hence, the current study can contribute to the body of knowledge by providing an integrative review of generic methods of physician-patient communication. Healthcare providers can use the findings from this review to make quality decisions concerning how to support patients and establish better patient-physician relationships.

This review aimed to explore the literature documenting research into cultural factors impacting the communication experience of patients and physicians in medical consultations, thus creating a mandate for this study and positioning it within the body of existing knowledge. The main objective is to explore the communication experiences of both patient and physician during the medical encounter, with the specific objectives of.

-

➢

Identifying cultural factors (barriers and facilitators) influencing physician-patient communication and how these factors impact the communication process.

-

➢

Identifying the cultural factors impacting communication outcomes.

-

➢

Exploring strategies applied by physicians to reduce the impact of cultural differences on medical consultation.

The question that guided this review was.

-

➢

What are the intercultural communication experiences of patients and physicians during medical consultations?

2. Materials and methods

An integrative review was adopted to research the body of literature because it incorporates the synthesis of knowledge with the applicability of the studies’ results to evidence-based practice [34]. The method is recognized as the broadest type of research review and facilitates the simultaneous inclusion of qualitative and quantitative research. Whittemore and Knafl [35] have structured the integrative review into five consecutive stages [1]: formulation of the problem [2]; collection of data [3]; evaluation of data points [4]; analysis and interpretation; and [5] result presentation. Defining the guiding research question in the beginning, is worthy because it informs which studies will be selected, defines the participants, and sets the context of the research problem [34].

2.1. Data sources and searches

The databases searched as primary sources of data collection included Medline/PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Review, all recognized as appropriate for health-related topics, as well as Google Scholar. A combination of keywords defining the research question and objectives were used to generate free text and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) search terms. The following combination of keywords and synonyms were used: Patient*OR Outpatient*, Physician*OR Doctor*OR “Medical Staff,” Communication OR Relationship AND “Transcultural,” Hospital OR “Outpatient Clinic” OR “Outpatient Service,” “Intercultural Communication,” OR “Transcultural Communication” OR “Cross-cultural Communication.” The researcher used broad search terms and synonyms to ensure that all studies that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved. A manual search was also performed to retrieve any missing studies. Two independent researchers searched the databases and then compared search results. After that, they screened selected studies after removing the duplicates using Endnote software. They followed two steps for eligibility assessment: title and abstract screening, followed by the full texts screening of eligible studies. Keywords were revised per database as required; for instance, some databases do not have a (MeSH) term structure. We used the PICOS framework to develop and structure the search, illustrated in Table 1 below. Studies were selected according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search Strategy.

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Physicians and patients who come from different cultural backgrounds. All types of Physicians (GPs, specialists, consultants) |

Physicians and patients who share the same culture Communication with health providers or health staff other than physicians |

| Interest/Intervention | Communication during medical consultations | Inpatient medical consultation, or any medical consultation in nursing homes and/or home-based care |

| Comparison | None | None |

| Outcome | Factors aiding or hindering communication | |

| Setting | Outpatient clinics and other clinics | Inpatients (patients hospitalized), including patients in mental health clinics |

| Study design | Original articles Qualitative, Quantitative or Mixed-method |

Reviews, systematic reviews, thesis, and conference proceedings |

| Language | English | All other languages |

| Publication date | 2008 to 2022 |

2.2. Search results

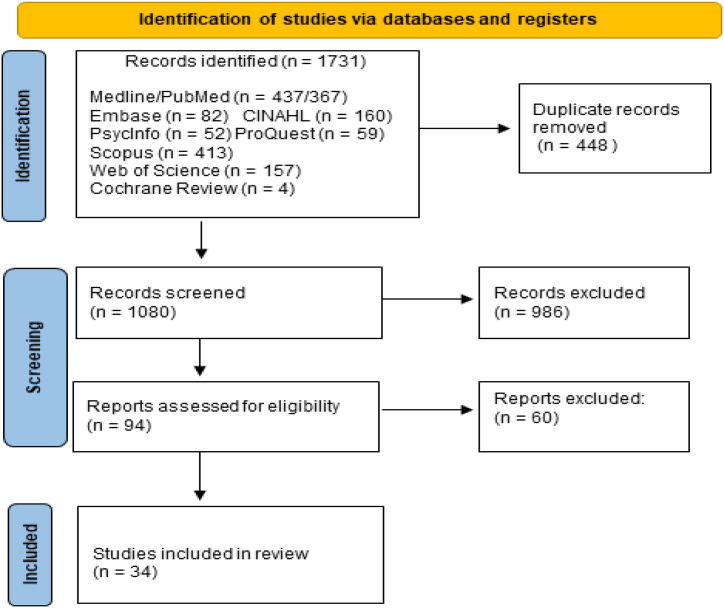

The specified databases and selected keywords yielded 1731 studies. The research process followed the recommended rules and protocols for conducting a reliable integrative review. The researchers adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, illustrated in Fig. 1 below, adopted from Moher, Liberati [36]. To avoid selection bias, the researchers were committed to the research protocol to select only the studies that met the inclusion criteria retrieved from the selected databases.

Fig. 1.

Research flow (PRISMA).

2.3. Data Reduction and extraction

Data were extracted from the 34 selected studies and assigned to one of ten fields, namely, author/year, objectives of the study and from whose perspective, concept and theoretical model used, research design, population under study, setting, sample size, aids/hindrances of communication attributable to cultural factors (review focus), social or other factors, and finally the study results. See the extraction table in Appendix 1.

2.4. Quality assessment of study

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of the selected studies [[37], [38], [39], [40]]. MMAT has been tested and proven to be a valid, reliable assessment tool [41]. MMAT consists of two generic questions (screening) that apply to qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods. This review used the 2018 version, updated from 4 to 5 criteria plus the two screening questions (see Appendix 2). The researchers conducted the appraisal process, prior to which they established a systematic protocol, as suggested by Pluye, Robert [42], to ensure optimum MMAT functionality. The assessment quality table in Appendix 2 shows how the studies were scored and evaluated. The average MMAT score for the selected studies was 80 %. However, some quantitative studies recorded a low score in the methodological criteria, attributable to a small sample size (see studies 18, 20, 3, 15, and 34 in the data extract and quality assessment table Appendix 1, Appendix 2). Nine of the selected qualitative studies failed to identify which qualitative approach they embraced in their studies (see studies 5, 1, 4, 7, 9, 16, 22, 21, 24 in Appendix 2). In an integrative review, different primary studies contribute various elements to the overall synthesis of evidence [43]. Given the few relevant studies, all studies that met the selection criteria were included, with limitations acknowledged.

2.5. Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis in research reviews involves ordering, coding, categorizing, and summarising the data from the primary sources into a unified and integrated conclusion regarding the research problem [35]. Data were extracted from the articles for the purpose of inductive content analysis. This involved a rigorous systematic process whereby the researchers made inferences from the data by translating context-specific information into general categories. NVivo software was introduced as a tool to manage, sort, and reduce the vast amount of data. The actual tasks of the analysis phases, such as coding, categorizing and theming, were accomplished manually. Limiting the use of NVivo enabled the researchers to humanize the analysis, using an intuitive process, and meant that the rigour of the research was not reliant on the ability to use the software [44].

2.6. Findings

A total of 34 studies were included in this review. Nineteen studies used a qualitative method, thirteen studies used a quantitative method, and two used a mixed methods approach. Seven studies were conducted in Middle Eastern countries, namely Israel [1], Iran [1], Saudi Arabia [4], and other Gulf countries [1]. One study from Africa was conducted in Kenya. Most studies were conducted in European countries: Netherlands [6], Switzerland [2], England [1], Italy [3], Greece [1] and Sweden [2]. The remaining studies were conducted in the US [7], Canada [1], and lastly Australia [3]. See the data in Appendix 1.

The literature search revealed that communication between physicians and patients has been broadly researched, though mainly focusing on the intra-cultural context [6,9,28,30,[45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50]]. Studies examining the impact of race and ethnic concordance between patients and doctors are inconclusive. These studies, conducted primarily with minority groups in the USA, indicate that race concordance has less impact on health outcomes than a doctor's communication style and ability to engender trust [51]. They confirm the importance of communication as the central mechanism for a successful patient-doctor relationship.

2.7. Physicians’ reported communication behaviour and experiences

Studies reported here describe physicians' perceptions, behaviours, and experiences regarding communicating with patients from different cultural backgrounds. Evidence suggests that physicians encountering patients from different cultural backgrounds display limitations in their communication behaviour [52]. Gao, Burke [52] observed videotaped consultations and reported white American physicians as having a biomedical focus and predominantly one-sided conversations with Chinese, Hispanic, and African American patients. The physicians were doing most of the talking with few questions solicited by the physicians or raised by the patients. Similar findings were reported by Shirazi, Ponzer [53], who examined the lived communication experience of Swedish physicians with Middle Eastern patients and their perceptions of communication in a videotaped medical consultation. Physicians pointed out insufficient attention and listening on the physicians’ part and very modest efforts to include patients in the decision-making.

Physician-centric communication behaviours were attributed to cultural differences, insufficient training, and years of experience. Other contributing factors identified included encountering shy or reserved patients, low educational level of patients and their health literacy, and system-related barriers such as lack of time [[54], [55], [56], [57]]. Studies conducted to examine the quality of physician-patient communication in the USA, Australia, and Saudi Arabia showed that the communicative behaviour of international physicians was authoritarian and bio-medically focused, with insufficient listening and time spent with patients preventing effective communication and decision-sharing [[58], [59], [60]].

Physicians in most reviewed studies perceived communication with patients speaking a different language as difficult, challenging, problematic, a barrier to relationship and rapport building with patients, and a source of frequent misunderstanding [54,59,61,62]. Amiri, Heydari [62], who interviewed fifteen Iranian physicians regarding their interaction with immigrant patients, illustrates the extent of the absence of mutual understanding. Most physicians indicated they could not understand most of what the immigrant patients said and vice versa. Other studies have recorded similar results of physicians’ unfavourable perception toward communicating with immigrant patients due to cultural differences, particularly gender issues [63,64]. For instance, Würth, Langewitz [64] conducted 19 interviews with Swedish physicians to examine their perceptions of encounters with Albanian and Turkish patients. Most physicians expressed frustration at their inability to perform the medical examination effectively and communicate openly and directly when meeting female immigrant patients because they were reserved and were sometimes accompanied by their husbands, who often communicated with physicians.

On the contrary, three studies showed that physicians perceived minimal or no difference in communication when meeting patients from different cultural backgrounds [55,65,66]. Cultural consultation services aimed at providing direct support to physicians who encountered cross-cultural communication barriers [54], focused development of skills to communicate with patients through professional training, continuous education programs, and culturally sensitive curriculum during residency training [64] and using reflective practices [65] enabled culturally sensitive approach to patient care. Paternotte [67] asked physicians to watch and reflect on their communication in recorded consultations with native and non-native patients. The physicians perceived little difference in communication with native and non-native patients. Another study in Saudi Arabia also showed that 51.9% of Saudi and non-Saudi physicians reported good rapport and effective communication with Saudi patients [68]. However, this finding is prone to bias because it relied on a self-evaluation in which physicians evaluated their communication skills.

Overall, compared to their encounters with patients from the same cultural background, studies demonstrated a significant difference in the physicians’ perceptions and communicative behaviour when encountering patients from different cultural backgrounds.

2.8. Patients reported communication behaviour and experiences

Studies reported here describe patients' perceptions, behaviour, and experiences regarding communication with physicians from different cultural backgrounds. Findings from these studies were inconclusive. Patients' experiences and their levels of satisfaction were varied; however, across the time period and in different countries, studies have reported that patients who are required to meet with physicians from different cultural backgrounds perceived poor quality of care and low levels of satisfaction with the medical treatment [17,19,[69], [70], [71]]. For instance, in one study, Chinese patients reported low satisfaction with white general physicians and perceived physicians more negatively than white patients did [71]. However, other studies demonstrated no difference in the medical treatment received or the patient's preference to meet physicians of the same ethnicity, race, or nationality [20,72,73]. Paternotte, van Dulmen [73] explored non-Dutch patients' preferences and experiences regarding their communication with Dutch doctors. Patients felt that the physicians' nationality was unimportant if they were professionals.

Moreover, a study conducted to gauge the perceptions of Saudi patients attending a primary healthcare centre of their doctors’ communications skills showed that Saudi patients expressed more satisfaction in communicating with non-Saudi physicians than with Saudi physicians [58]. However, the majority of studies indicated that in the context of physician-patient intercultural medical encounters, most patients reported inferior communication levels, difficulty in understanding and being understood by their physicians, frustration due to the inability to express themselves effectively, and concern due to their inability to communicate their health problem due to language differences [17,64,[69], [70], [71],74]. In the United Kingdom (UK), Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani patients reported poorer communication than white British patients [74]. In Australia, studies have described how patients had to seek help from other physicians who were either Australian or born and trained in Australia to understand the explanations and diagnoses of international physicians. In contrast, other patients rebooked appointments with Australian physicians [63,75].

Differences in patient behaviour have been shown to impact communication and communication outcomes. Communicating with Italian patients was challenging during the discussion of anthological problems in Santi, Spaggiari [50]. Non-Western patients were observed to exaggerate respect for physicians, which negatively reflected their engagement in decision-making and participation in the consultations [53]. Woodward-Kron et al., confirmed this finding, who demonstrated the significant difference between how Australian patients and non-Western patients interact with their physicians [63]. It showed that non-Western patients submit to a hierarchical paradigm, while Western patients, such as Australians, adopt an egalitarian paradigm when interacting with their physicians. The issue that both studies are referring to is also described as power distance and used alongside similar terminology such as ‘directiveness’ and ‘goal-oriented’ behaviours to distinguish the communication style of patients belonging to collectivistic cultures (non-Western) from patients belonging to individualistic cultures (Western). Some studies showed that non-Western patients displayed non-goal-oriented behaviour and high-power distance, and indirective behaviour compared to Western patients, which impacted the quality of communication with their physicians [17,52,62]. For instance, in contrast to the Dutch patients, the study of Schinkel, Schouten [17] showed that Turkish patients were uncomfortable with the GP's direct and confrontational communication style in asking direct questions, did not limit their discussions with GPs to their health problems, and showed high-power distance in the medical consultation. This confirmed a cultural perception by indicating that the physician knows best and is responsible for health-related decisions; hence, the physician should decide on the diagnosis and treatment. Other studies indicated similar results, particularly that non-Western patients' communicative behaviour was seen as a barrier to effective communication.

In contrast to Western, non-Western patients were shy and conservative, especially surrounding sexuality and genital examination. Thus, it was perceived that they avoided direct communication and were overly sensitive toward receiving treatment from physicians of the opposite sex due to the conflict with their customary practices or religious beliefs. Non-Western patients were often observed to avoid proactivity, actively engage in the consultation, provide and requested less information, and demonstrate low health literacy [56,62,76,77]. However, other studies showed that the widespread belief that non-Western patients were inclined to be less proactive and less directive in their communication with physicians than Western patients was not valid [52,78].

2.9. Intercultural consultations reported outcomes

The purpose of a medical consultation is well described in the literature and generally well acknowledged across populations and countries. There is an expectation that specific outcomes will be achieved [79]. However, evidence suggests that inter-cultural consultations compromise outcomes [53]. This theme explores the influence of culture on the physician-patient intercultural encounter, particularly in relation to health-influencing outcome factors such as trust, patient safety, patient medical adherence, patient continuity of care, and physician's ability to practice. In terms of trust, studies showed that a difference in ethnicity, race, or nationality between a patient and a physician entails linguistic and cultural differences that provoke distrust, particularly from the patient [20,59,61,62]. A study by Miller, Kinya [20] conducted in Kenya to examine the impact of ethnicity discordance on the physician-patient interaction showed that patients placed more trust when meeting physicians sharing the same ethnicity but stated that they are most likely to trust physicians with medical competence regardless of their race. Similar findings were reported by other studies showing that developing a trusting physician-patient relationship requires more time in intercultural encounters than intracultural encounters. Further studies confirmed the association between cultural differences between physicians and patients and the trust factor. A study conducted in the USA illustrated that physicians could gain a Spanish patient's trust simply by speaking some Spanish and showing basic knowledge of Spanish culture [65,70]. Nonetheless, in some reported intercultural encounters, the issue of trust was attributed mainly to the patient's perception of the medical competence of the physician, regardless of nationality, race, or ethnicity [20,52,53,65,70]. In terms of health outcomes, culture and language differences have strained physician-patient communication and directly impacted outcomes such as patient satisfaction and physicians' job satisfaction, as presented in the previous two themes. Furthermore, differences between physicians and patients reflected indirectly on important health outcomes such as patient safety, patient's medical adherence, patient's continuity of care, and physician's ability to establish credibility and diagnose correctly [52,62,69]. On the impact of language in establishing credibility, Shirazi, Ponzer [53] reported a physician unable to convince an Iranian woman suffering from a fractured femur to undergo surgery until one of the Iranian staff helped him translate and convince the patient of the need. The influence of cultural and language differences between patients and healthcare providers was obvious in the medical consultations, but most reviewed studies focused on the language aspect. This might be explained by the fact that language differences are more prominent. Language difference was mentioned frequently in all the reviewed studies. Moreover, some studies showed the influence of other language-related factors such as accent, dialect, lingo and local slang usage, and even medical jargon on the mutual understanding between physicians and patients [59,62,63,73,75]. Nevertheless, physicians speaking a different language from patients and not having a second language shared by the two parties was the main problem reported in the reviewed studies. Thus, it was not surprising to find an emphasis on providing translation services to mitigate language problems. Some studies showed the unexpected negative consequences of using a translation aid, such as the possibility of breaching confidentiality, blocking of information disclosure, patient discomfort, inaccuracy in conveying the health message between physician and patient, and the time and expenses associated with providing translation services [61,65,78]. Schinkel, Schouten [17] illustrated that the patient use of informal translators, particularly sons and daughters, led to incomplete information, inhibiting patients, translation errors, and a tendency to exclude the patient from participation.

2.10. Mitigating skills and behaviours

This theme concerns physicians' readiness and preparedness to deal with and treat patients from different cultural backgrounds. The studies demonstrated that most physicians not only lack cultural competence skills, such as being familiar with the patient's cultural experience or speaking few words of the patient's language, but also lacking competency in generic communication skills needed in any standard medical consultation [66,73].

Regarding generic communication skills, there was evidence of a lack of basic communication skills among physicians, such as listening, explaining, paying attention, and asking and receiving questions to engage the patients [53,61,62,64]. Shirazi, Ponzer [53] pointed out that physicians did not listen or demonstrated ineffective listening to patients and paid insufficient attention by showing no eye contact and speaking with low tone and pitch. Two quantitative studies conducted in Saudi Arabia to measure physicians’ communication skills and estimate the percentage of physicians with good rapport with patients concluded the need for physician training in generic communication skills [54,68]. This finding is confirmed by another Saudi study conducted by Senitan and Gillespie [80], which showed an overall low rating of physician communication skills and demonstrated a close relationship between the quality of physician communication and patient satisfaction. However, it is necessary to assume that the generic communication skills of physicians can be impacted by the differences with patients. For instance, physicians interacting with patients from different backgrounds might have good generic communication skills but be impeded by the language. International physicians generally showed less competence in generic communication skills than national or local physicians. However, most studies sampled only foreign physicians so that a methodological bias could have negated a fair comparison between international and local physicians. Regarding cultural competence, one-third of the reviewed studies pointed out a lack of cultural competence and called for the inclusion of cultural sensitivity in curricula and formal workplace training [56,65]. Physicians also reported that they felt unprepared to provide culturally competent care. For instance, in a Swedish self-rating evaluation study, physicians regarded themselves as less capable in intercultural communication skills than in basic medical skills [81]. Schouten Schouten, Meeuwesen [82] conducted a study comparing GP communication with Dutch and ethnic minority patients. They found that physicians intended to focus entirely on their generic communication skills rather than applying specific ICC skills when meeting patients from different cultural backgrounds.

Other studies demonstrated the benefits gained by acquiring cultural competence and perceived cultural competence to mitigate cultural and linguistic differences between physicians and patients [17,19,53,55,77]. For instance, these studies illustrated how physicians with adequate cultural competence and more years of experience encountered fewer difficulties and showed more extraordinary ability in treating and understanding immigrant patients than inexperienced physicians with insufficient cultural competence. This finding is confirmed by a study conducted in El Paso, New Mexico where Mexicans accounted for 80 % of the study population [65]. The above study reported better communication between physicians who knew some Spanish and understood the health beliefs of the patients in comparison with physicians with insufficient cultural competence skills. Dominicé Dao, Inglin [55] conducted a study in a Swiss hospital to examine the impact of a Cultural Consultation Unit (CCU), in which they analysed 236 physicians' cultural consultation requests and interviewed 51 physicians regarding their perceptions of the benefits of the CCU. The purpose of the CCU is to accommodate patients with different cultural backgrounds by providing direct support for physicians who might encounter difficulties. In Dao's study, most physicians reported that the CCU improved their cultural competence and reflected positively on their communication and relationship with patients.

Besides the application of cultural competence, studies reported some convergence strategies physicians use when interacting with patients from different cultural backgrounds, such as speaking slowly, repeating information, checking frequently if the patient understood an explanation, and using non-verbal communication [59,66]. In Woodward-Kron et al., physicians reportedly applied strategies like using their smartphones to access Google Translate, drawing diagrams, and using brochures or the Internet [63]. These strategies can be used as training and educational materials for recently qualified physicians and those with little experience interacting with patients from different cultural backgrounds.

3. Discussion

The objective of the current study was to explore and summarize the recent literature on the factors affecting patient-physicians’ communication experience in intercultural settings. The primary study findings are summarized into four themes which are physician-reported communication behaviour and experiences, patient-reported communication behaviour and experiences, intercultural consultations reported outcomes, and mitigating skills and behaviours. The findings suggest a difference in physician's communicative behaviour when encountering patients from different cultural backgrounds compared to encounters with patients from the same cultural background. When communicating with patients from different cultural backgrounds, physicians were found to be authoritarian, have a biomedical focus, and do not involve patients and relatives in decision-making. Generally, findings from studies about patients' behaviours during consultations and experience and perception of quality of care in the context of ICC were varied and inconclusive. Often, patients were found to exaggerate respect for physicians, feeling uncomfortable with the direct communication style of physicians, show a less proactive attitude, demonstrate low health literacy and feel shy. These behaviours were attributed to language differences, differences in perception of illness and disease, perception of health communication, prejudice, assumptions, training experience of physicians, and systematic issues like time allocated for consultations. Ineffective communication in intercultural consultations was found to impact patient satisfaction, physicians' job satisfaction, patient's medical adherence, patient's continuity of care, and physician's ability to diagnose correctly. These are the most significant factors that affect the ICC process between patients and physicians. The studies included in this review demonstrated that most physicians not only lack the cultural competence, such as being familiar with the patient's cultural background or speaking few words of the patient's language but also lack competency in generic communication skills needed in any standard medical consultation. Therefore, mitigation strategies focusing on these two aspects may improve patient-physician communication experience in multicultural settings.

Information sharing during consultation between patients and physicians mainly depends upon effective communication. Communication problems occur in intercultural settings. Ineffective communication leads to dissatisfaction, low quality care, and frustration among patients and physicians. Previous studies [[54], [55], [56],58,59] reported that due to communication issues, insufficient attention is given to the patient by physicians, and little effort to involve patients in decision-making. Further studies [[54], [55], [56]] reported that the shy nature of the patient, low education level, lack of time, and health literacy also play significant roles during medical consultation. Ineffective communication would affect the patient-physician relationship increase distrust and misunderstanding between patients and physicians. In the same way, patients consulting expatriate physicians shows similar concerns, such as low level of satisfaction and quality of care. A study among Sub-Saharan African students revealed that international patients believed that friendliness from healthcare providers was a signal that they were dealing with a reasonable care provider [82]. On the contrary, Paternotte, van Dulmen [73] reported that their nationality does not matter if physicians are experienced and professional. Patients also struggle to express themselves and are unable to convey their message to physicians. Other studies have highlighted power distance during medical consultation in some countries. The reason for such power distance is that there is a perception that physicians know more and is the best person to decide diagnosis and treatment [17,52,62].

Regarding intercultural consultation and outcomes, culture influences the patient-physician relationship, trust, patient continuity of care, and patient safety, and raises questions about physician's ability and competence [20,59,62]. Furthermore, physicians' preparedness and readiness also play an essential role during medical consultation. Physicians must be aware of patients' cultural backgrounds to pay enough attention to patients during consultation [73]. Abdulai et al. suggested that the health systems should consider linguistic abilities and cultural sensitivity when posting healthcare providers to areas characterized by multiple languages and dialectal variations [83].

Overall, there is agreement among the findings of the studies about the impact of physician-patient ethnic, racial, or national discordance that entails cultural and linguistic differences preventing effective communication, mutual trust, and positive health outcomes. Only three studies illustrated that physician-patient discordance has no impact, particularly on patient satisfaction concerning communication with physicians, patients' preference for physicians with the same cultural backgrounds, and patients' perception of physicians' medical competence [20,58,66]. Except Paternotte, Scheele [66] study, there is significant agreement among the studies on physicians’ lack of generic communication skills and cultural competence. Studies conducted in countries with multicultural populations, such as Canada, Australia, and the USA, were most likely to report positive outcomes. Conversely, studies conducted in countries with mono-cultural societies where expatriate physicians were employed reported more significant communication difficulties. The same can be said in the case of patients who are recent immigrants. The findings indicate the need for further studies that test implementing strategies designed to facilitate effective communication between patients and physicians in the intercultural context. The most common solution proposed for communication problems was the development of physician cultural competence. However, more studies are required to examine cultural competence training, particularly in Middle Eastern countries, and other ways to enhance communication.

Except Schinkel, Schouten [83], all qualitative studies on ICC focused on minority patients such as immigrants and refugees. This can be understood since minority patients are known to be underserved and at a more significant disadvantage than indigenous patients. However, examining ICC from the perspective of indigenous patients is of paramount importance due to globalisation, particularly in the movement of international physicians, which increases the chance of patients encountering physicians with different cultural and linguistic backgrounds, such as in the case of Saudi Arabia. Studies conducted in Saudi Arabia or neighboring Gulf region countries have examined intercultural communication purely from a quantitative approach [54,58,61,68,80], which limits the ability to draw a complete conclusion about the status of physician-patient intercultural communication in that region.

In terms of applied theories, only three of the 31 studies applied an existing theory. The Cultural Theory of Identity [84] was used by Scholl, Wilson [70] to understand how the cultural identity of a patient influences physician-patient communication. The Cultural Theory of Accommodation [85] was applied by Jain and Krieger [59] to show how international physicians mitigate language differences with patients by applying strategies such as repeating sentences, changing the pace or volume of their speech, and using non-verbal communication to compensate for language differences. The third theory used in the review was linguistic theory [17], which is not exclusively about language; it has an enabling factor and a predisposing factor. The theory was applied by Schinkel, Schouten [17]. The enabling factor was the patient's inability to communicate with the physician in a language other than their mother tongue. In contrast, the predisposing factor was considered as the patient's in-grained culture, which impacts communication with the physician.

The Gulf Cooperation Council countries, including Saudi Arabia, achieved remarkable development in the health sector, but intercultural communication issues among expatriate physicians and patients become a challenge. As a result, patients face several problems at the time of consultation. To effectively manage these communication issues, strategies must be formulated to reduce communication barriers and improve the quality of health services. In addition, planning for the health workforce needs adequate and appropriate strategies that should reflect all aspects, including language and skills, to meet the population's future demands and achieve health sector vision.

3.1. Implications

A greater understanding of cultural diversity in healthcare is essential to understand the health values, beliefs, and behaviours of different cultures. Hospital administrators and policymakers in the health system must take the necessary steps to overcome the issue of cultural differences among patients and physicians. Moving forward, the cultural competencies of expatriate physicians require teaching them about Saudi culture and preparing them to apply those competencies in practice. Expatriate physicians must be provided adequate training in patients’ language and culture, including generic communication skills. The Ministry of Health should consider developing policy guidelines and recommendations that promote patient-centred, culturally appropriate healthcare in all healthcare settings. The policy should also consider the inclusion of an evidence-based approach to intercultural communication, including incorporating cultural issues in medical curricula, educational programs to develop expatriate physicians' cultural competencies, and a longer consultation time for a patient from a different culture.

This review has also highlighted the dearth of research on physician-patient intercultural communication in the Saudi Arabian context and the necessity for more studies to explore how intercultural communication might be enhanced thoroughly. Therefore, future research on this topic may include intercultural interviewers as mediators. It is also necessary to conduct more studies on how Saudi and non-Saudi physicians communicate with one another and how to enhance expatriate physicians' communication competencies. It is also recommended that a new instrument to measure physician-reported communication behaviour and experiences, patient-reported communication behaviour and experiences, intercultural consultations reported outcomes, and mitigating skills can be developed and validated in the Saudi perspective, which would be a valid contribution towards the body of knowledge in this field.

3.2. Limitations of the study

This integrated review has the following limitations. Firstly, there are limited articles, literature, and empirical evidence available in this area that can explain the subject matter in depth and describe the current situation. Our search was limited to studies published in English, so studies published in other languages were not included. Although the authors believe that the search method was comprehensive, the exclusion of articles published in other languages may have affected the comprehensiveness of this study. Moreover, the time lag and time of search completion and publication of the final papers studies on this topic may have been missed. Nonetheless, the viable solutions to the ICC issues in the reviewed articles might help overcome such problems from the Saudi perspective. There is a need for more exploration of this subject matter. Secondly, the authors' knowledge regarding physicians' and patients’ challenges of intercultural communication and their solution is limited to the data and evidence documented in the reviewed articles.

4. Conclusion

This review aims to explore and summarize the current literature examining the cultural factors impacting the communication experience of patients and physicians in healthcare settings and provide an evidence-based solution. The findings of the review revealed that challenges of intercultural communication between physicians, intercultural consultations reported outcomes, and mitigating skills and behaviours are inter-wound issues that affect the satisfaction of both physicians and patients and the quality of health services. Cultural competence and generic communication skills of physicians are key in intercultural consultations. To cope with these challenges effectively, health policymakers should pay more attention to the importance of medical consultations in cross-cultural settings to facilitate the interaction between patients and physicians.

The socio-cultural situation of Saudi Arabia is entirely different from most countries, and health policymakers need to develop policy guidelines and recommendations that promote patient-centred, culturally appropriate care in all healthcare settings. The policy should also consider incorporating an evidence-based approach to intercultural communication in all healthcare settings. The emphasis should be on developing the cultural competencies of expatriate physicians, who constitute more than half of all physicians in the Kingdom. The MOH should prioritize developing skills of health professionals to communicate with patients through professional training, continuous education programs, and introducing culturally sensitive curriculum during residency training. Further research is required on physician-patient intercultural communication and ways to enhance intercultural competencies in the Saudi Arabian context.

Data availability

Data included in article/supplementary material/referenced in article.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the deputyship for Research and Innovation, Ministry of Education, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research work through the project number (QU–IF–4-2-4-30046). The authors also thank Qassim University for their technical support.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohammad Alkhamees: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ibrahim Alasqah: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix 1. Data Extraction Table

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Paternotte, Emma van Dulmen, Sandra --------------- (2017) |

To explore patients' preferences and experiences regarding intercultural communication (language only) – patients' perspectives |

Patient-centred communication Language concordance | Netherland – Sample: 30 non-native patients – Qualitative interviews |

Ethnicity or race are assumed to be a challenge when communicating to a doctor from different cultural background | Language | Gender Professional Knowledge of the healthcare organisation | -No patients preference regarding the doctor's background ethnicity -Emphasis on generic communication skills - A close link between intercultural communication (ICC) and patient-catered care (PCC). |

| 2 | Dao, Melissa Inglin, Sophie Vilpert, Sarah Hudelson, Patricia -------------- (2018) |

To identify the cross- cultural communication challenges (social, cultural) – Physicians' perspective |

Cultural sensitivity | Geneva, Switzerland – Sample: 51 clinicians & analysed 236 cultural consultation requests – Qualitative: Interviews& documents analysis |

Challenges caused by the migration of patients' cultural differences with the physician | Illness-related beliefs Language Mistrust Norms | Factors founded to have an impact are: Financial, administrative, and immigrant legality issues. |

Even though physicians benefited from the training and CCS, we are unable to say whether contact with the CCS has led to more or better clinical interviewing on the part of clinicians. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Aref Ibrahim Alabed -------------- (2017) |

To examine the impact of differences in nationality between physician and patient – Both of the physicians'& patients' perspectives |

– | Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries – Sample: 100 patients, 50 doctors and 50 from other healthcare specialists – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Differences in nationality between patient and physician lead to some problems during the medical encounter – Communicational skills Tolerance, training, emotional intelligence |

Trust, emotional intelligence, understanding | Generic communicational skills | -Differences in nationality result in communication gap between physician-patient -Proper communication is necessary to build Physician- patient relationship |

| 4 | Rana Amiri, Abbas Haidari, Nahid Dehghan, Abou Ali Vedadhir, Hosein Kareshki -------------- (2016) |

To explore the healthcare staffs' experience in regard to caring for Immigrants in Mashhad- Iran. – Physicians' perspective |

Transcultural care | Iran – Sample: 15 participants (seven doctors and eight nurses), – Qualitative: Interviews |

Problems that arise from caring for patients who are culturally diverse | Religion Norms Language Dialect Health beliefs Gender rules | Immigrants' financial and legal statues | -In transcultural care, cultural differences between patients and physician impact greatly in the healthcare provided |

| 5 | Akins, Ralitsa (2009) | To assess the cultural sensitivity impact – Physicians' perspective |

cultural competence cultural sensitivity | USA – Samples:60 physicians – Qualitative: Focus group |

-Ignoring cultural sensitivity – -Adopting cultural sensitivity -cultural competence training & teaching |

-Religion -believe -Custom, norms -Language |

formal curriculum in teaching cultural sensitivity | -Being aware and sensitive to patients' culture results in good physician-patient understanding. In contrast, ignorance of cultural competence results in assumptions that lead to stereotyping. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Amanda Whittal, Ellen Rosenberg --------------- (2015) |

To explores how acculturation orientations of Canadian doctors and immigrant patients impact the doctor- patient relationship and communication – Both of the physicians'& patients' perspectives |

-acculturation orientations - Berry's acculturation model |

Canada – Sample: 10 participants (5 patients&5 physicians) – Qualitative: Observations& interviews |

The inability of the ethnic patients to integrate (acculturation) in the host culture hampered the physician-patient communication. – The acculturation by the ethnic patients enhance and reduce the physician-patient differences in the medical visit. |

Language Health beliefs Cultural expectations and norms | -Education -Understanding the health system -Period of staying in Canada |

-The study has shown that combined acculturation orientations of the doctor and the immigrant patient influence the doctor-patient relationship and communication. -Understanding the ethnic patients' acculturation orientations might help in improving the physician- patient interaction. |

| 7 | Ge Gao Nancy Burke Carol Somkin Rena Pasick --------------- (2009) |

To know if cultural practices (i.e., communication norms and expectations) influence patients' and their physicians' communication – Both of the physicians'& patients' perspectives |

Cultural communication style | USA – Sample:44 of videotaped of medical visits & 44 of doctors & patients – Qualitative: Interviews & observation |

Differences in cultural styles (norms, expectations) between patients and physicians | -Power distance -orientation toward time -low and high- context communication styles |

directness/indirectness, and an ability to listen, as well as personal health belief that comes from past experience for example not from the effect of culture | -The study showed inability to find explicit references to cultural differences in physician-patient communication. It showed that power distance, trust, directness/indirectness, and an ability to listen, as well as personal health beliefs, affect the patient definitions of effective communication. Also, discordant physician– patient impact the communication |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Hans Harmsen Roos Bernsen Marc Bruijnzeels Ludwien Meeuwesen ---------------- (2008) |

To identify which cultural and language barriers that impact the quality of care – patients' perspective |

– | Netherlands – Sample:663 patients – Quantitative: questionnaire |

The diversity of patients' backgrounds results in different needs, expectations from the healthcare provided | -cultural views (gender roles, secularisation, religiosity, and individualism, collectivism) - language issues |

-age, -gender, education, acculturation |

-In any event, differences in patients' cultural views and language proficiency do influence patient-physician communication and consequently patients' perceptions about the quality of care. |

| 9 | Kell Julliard Josefina Vivar Carlos Delgado Eugenio Cruz Jennifer Kabak Heidi Sabers --------------- (2008) |

To clarify which factors, reinforce nondisclosure of health information in clinical encounters between Latina patients and their physicians? – patients' perspective |

– | USA – Samples: 28 Latina women – Qualitative: In-depth interviews |

Patients' information disclosure is impacted by their cultural background | Language Gender preference Culture customs & expectations | Physician-Patient relationship was affected by privacy invasion and financial such having insurance, Sensitive Issues such as (STDs) | -Six main themes emerged related to the disclosure of health information: the physician-patient relationship, language barriers, time constraints, sex and age differences, sensitive issues, and culture and birthplace |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | P McGrath, D Henderson, J Tamargo, HA Holewa ---------------- (2012) |

To explore the impact of cultural factors on IMG doctor−patient communication as perceived by the IMGs. – Physicians' perspective |

Patient-centred communication | Australia – Sample: 30 IMGs, – Qualitative: Interviews |

Challenges arises because patient- centred communication as a model is unknown or unfamiliar for IMGs. So, the switch from paternalistic model to this modern model was difficult. | Culture norms (The culture of origin of these IMGs can be described as paternalistic (doctor- dominated communication) ) |

– | Findings came to be relegated to: -Cultural background – in many of the countries of origin, it is usual for patients to do what the doctor decides without question; in country of origin it is common for the physician to talk to the family not the patient) to the very different healthcare culture of Australia (where patients are perceived to be more educated and informed consumers that demand high levels of information and discussion) |

| 11 | Ann Miller Jesica Kinya Nancy Booker Mary Kizito Kyalo Ngula ----------------- (2011) |

To explore the patients' attitudes regarding doctor ethnicity – Patients' perspective |

doctor–patient ethnic discordance | Kenya – Sample: 221 patients – mixed quantitative questionnaires & focus group |

Differences in ethnicity between patients and physicians might be: 1) a barrier for some patients for communicational reason 2) It is not a barrier for other patients. |

Language Trust | -Medical competency -cost of service |

-Matching ethnicity was not the main concern for patients when they asked to see a doctor. However, when their illness is not severe, they prefer to see a doctor from the same ethnic group for communication purposes. On the other hand, when the illness is serious, they prefer to see European or Indian doctors |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | S. Ohana R. Mash2 ----------------- (2015) |

This research examined differences between the ways the physicians perceive their cultural competence and the way their patients perceive it – Both of the patient and physician perspectives |

Cultural competence | Israel – Sample: 90 physicians & 417 patients – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Problems might arise from the differences in perception of cultural competence between patients and physicians. | Cultural backgrounds | Gender- women physicians showed better communicational skills than male physicians | -The more patients assess their physicians as culturally competent, the more satisfied they are with their medical treatment. Also, a relationship between the cultural backgrounds of the medical staff and of the patients and the probability of conflict existing between them. In addition, when physicians and patients were from the same cultural background, the gaps narrowed and the patients' satisfaction increased. |

| 13 | E.Paternotte F.Scheele T. R.van, Rossum. M.C.Seelema nA.J.J.A Scherpbier. A. M.van Dulmen, ---------------- (2016) |

This study explored how doctors evaluated their own communication with native versus non- native patients – physician perspective |

– | Netherlands – Sample: 17 medical specialists – Qualitative: interviews |

Communication with patients who have different cultural background is not that a much of a barrier and has little difference when communication with patient who have the same background | Language values, views Expectations religion | Personal characteristics such as education level, being responsive and assertive during the medical visit | -Little differences in terms of communicating with non- native verse native patients. Personal characteristics such as education impact more on the communication than cultural factors such as language. Physicians assume themselves to apply intercultural communication skills but they are not. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Ahmed, F. Abel, G. Lloyd, C. Burt, J. Roland, M. ------------- (2015) |

To examine if the language concordance in practices improves doctor- patient communication – Patients' perspective |

language concordance | UK – Samples: 190,582 patients – Quantitative: survey |

Problems that arise from differences in ethnicity between patients and physician impact the quality of communication | Language | – | Poorer patients' communication experience was associated when patients of different ethnicity encountered white doctors. Language concordance showed positive communication impact. |

| 15 | Ken Russell Chardee Galan (2012) | To test physicians' abilities to decode nonverbal emotions across cultures. – Both of the patient and physician perspective |

Non-verbal communication | USA – Sample: 30 physicians & 60 patients – Quantitative: Survey& Media Lab software |

The study hypotheses that cultural difference between patients and physicians will make it harder for the physicians to read and understand the non- verbal communication indicators in comparison with patients sharing the same cultural background. |

Cultural backgrounds | – | Contrary to what might have been expected, the ability to read and understand patients' non-verbal communication indicators is the same whether the physicians have the same cultural background with the patient or a different one. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Juliann C. Scholl, Jacquee B. Wilson, and Patrick C. Hughes -------------- (2011) |

To investigate how patients display their ethnic identities during intercultural patient–provider interactions. – Both patient and physician perspective |

Communication Theory of Identity | USA – Sample: 8 Physicians & 50 Patients – Qualitative: Document analysis |

There is a connection between ethnic differences between patients and physicians might lead to communication problems in the medical interview | Language. very main -views, religion, ideas- very minimal |

– | -There is a connection between ethnic differences and communication problems in the medical interview. The ‘othering’ concept was manifested in the patients' experiences. However, some of the participants stated that they very rarely experienced ethnicity-related issues |

| 17 | Sanne Schinkel, Barbara C. Schouten, Julia C.M. van Weert --------------- (2012) |

To investigate if the non-native patients experience more unfulfilled information needs than native-patients – Patients' perspective |

– | Netherlands – Samples: 117 native-Dutch patients &74 Turkish-Dutch patients. – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Ethnicity differences might influence the amount of information that patients receive from their physicians. | Differences in ethnicity | Acculturation | -Non-native patient such as Turkish experience more unfulfilled information needs that the native-patients (Dutch). -In general, finding shows that physicians provide insufficient information for both native and non-native patients. -Also ethnic factor showed that Turkish patients report higher needs for information on prognoses, physical examination, medical terms, and procedures. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | Barbara C. Schouten. Ludwien Meeuwesen. Hans A. M. Harmsen --------------- (2008) |

To examine the communication style of general practitioners when meeting with ethnic patient in comparison to Dutch patients. – |

Patient- centredness -Paternalism medical model -Autonomy medical model. |

Netherlands – Sample:103 GPs – quantitative: survey |

Because of ethnicity, this study assumes that GPs will interact with ethnic patients less adequately than Dutch patients | Differences in ethnicity that entails language, views, preference, religion, custom | Age Gender | -General practitioners (GPs) communicate less with ethnic minority patients in comparison to Dutch patients. -GPs tend to involve ethnic patients less in decision- making, GPs seem to check less often with ethnic patients. |

| 19 | Jessica Sommer, William Macdonald, Caroline Bulsara, David Lim ---------------- (2012) |

To identify non- Australian physicians' perceived communication barriers when meeting Australian patients and working with Australian physicians. – Physician perspective |

– | Australia – Sample: 7 physicians (total five IMG and two Australian trained doctors ATD) – Qualitative: interviews |

Barriers to communication are provoked when Australian patient meet international doctors in the medical consultation. – Training program for dealing with patients who cultural background is different can enhance the communication. |

Language accent Religion Custom | Communicational style such as autocratic verse partnership | -There are some barriers that were caused by the cultural background differences in terms of language, accent, treating the opposite sex. Also, there were some communicational problems between international doctors and Australian doctors but not significant. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | Eivor Wiking Nuha Saleh- Stattin. Sven-Erik Johansson Jan Sundquist ---------------- (2009) |

To explore the ethnic patients' experiences and comments regarding the consultation and cross-cultural communication. – Patients' perspective |

Patient-centred communication | Sweden – Sample: 78 immigrants' patients – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Many patients stated that differences in language and culture (between them and the GP) could cause problems during the consultations. – Interpreter can reduce the differences excited but it can complicate things. |

Language Culture- indication to expectations and customs | Patients' focus Personality respect education | -There was no relation between migration-related factors were not related to the outcomes. 85 % of the patients felt that the doctors understood their problems but not being patient-centred is the doctors' problem part. However, in the qualitative part in the questionnaire, patients believed that differences in language and culture could cause problems during the consultations |

| 21 | Woodward- Kron, C. Fraser, H. Rashid, J. Au, Y. E. Chua ---------------- (2016) |

To examine the perspectives of doctor and senior staff in regard to junior doctor intercultural communication – Physicians Physicians& senior health staff perspectives |

– | Australia – Sample:30 junior doctors and 4 senior professional staff – Qualitative: Focus group & interviews |

Differences in language and culture was seen as a barrier by physicians. – Putting more emphasis in the importance of CC in terms of medical curricula and teaching might reduce the communication |

Language (no English, accent, slang) Religion Customs and norms that are associated with gender roles. |

– | -Language and culture (religion, customs, and gender roles) were found to be barrier in the medical consultation. Language is not restricted on speaking the language but more like knowing the slang, and having no accent. |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | Sanne Schinkel, Barbara Schouten, Fatmagül Kerpiclik, Bas Putte & Julia Van Weert --------------- (2018) |

To explore perceptions of barriers within ethnic patients and indigenous patients in regard to participation in medical visit. – Patients' perspective |

Street's linguistic theory |

Netherlands – Sample:5 to 10 patients in each conducted focus group – Qualitative: 8 Focus group |

Perceptions of barriers existed in the ethnic patients impede the participation in the medical consultation | Language Low-high context Power distance Individualism/co llectivism |

Education level | -Two perceptions of barriers emerged in regard to regard to ethnic patients' enabling factors to participate: Dutch language proficiency and preferred communication style. These perceptions of barriers did not emerge among indigenous Dutch participants |

| 23 | Patricia Hudelson, Noelle Junod Perron, Thomas Perneger -------------- (2011) |

To assess the physicians' intercultural communication skills – Physicians perspective |

– | Switzerland – Sample:619 participants (physicians & medical students) – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Differences in language and culture during the medical encounter hampered the physicians and patients' interaction – Physicians' intercultural communication skills enhances the physician-patient interaction and communication |

Things that were measured in relation to culture are: -Language -Cultural beliefs in regard to illness -religion -Traditional therapies |

– | -Overall, physicians rated themselves as less competent in intercultural tasks compared to basic medical skills Also, they rated themselves less competent at specific intercultural communication skills than at general intercultural skills. Physicians with long experience in intercultural communication rated themselves high in intercultural communicational skills |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | Parul Jain, Janice L. Krieger ------------- (2009) |

To understand the communication strategies used by international physicians in medical interactions to overcome language and cultural barriers – Physicians perspective |

Communication Accommodation Theory | USA – Sample:12 of international physicians – Qualitative: Interviews |

Differences existed make it difficult for international physicians to converge their communication to meet the national patients. – Convergence strategies used by physicians can reduce the communicational barriers in the medical visit |

-Language (accents, tone, voice inflection, and pace. Pronunciation) - Cultural norms, expectation |

– | -The study found that international physicians apply some strategies during the medical encounter such as: -repeating their sentences or by changing the pace or volume of speech. -Check with patients again to make sure if they got it. Use non-verbal communication to compensate the language issue. -Changing their communication style from paternalistic to partnership one. |

| 25 | Ayat A. Al Ali, Ahmed G. Elzubair (2016) | The impact of establishing rapport on physician– patient communication and patients' satisfaction Patients and physicians' perspectives |

– | Saudi Arabia Sample: 374 patients and 27 physicians – Quantitative: questionnaire |

Nationality difference | religions and cultures, languages | Personal characteristics, age, education, experience and type of illness, chronic, cute | -The lack of building rapport in Saudi may be explained by the fact that working physicians are of different nationalities, language, religions cultures from the patients speak different languages. -Need for training in communication skills |

| Study No. | Author/Year | Objective/perspective | Concept/theoretical Model | Context/Sample Paradigm | Aids & Hindrances | Link to cultural factors (the study focus) | Link to social and other factors | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|