Abstract

Interleukin-17A (IL-17A) levels are elevated in patients with asthma. Ferroptosis has been identified as the non-apoptotic cell death type associated with asthma. Data regarding the relation of ferroptosis with asthma and the effect of IL-17A on modulating ferroptosis in asthma remain largely unclear. The present work focused on investigating the role of IL-17A in allergic asthma-related ferroptosis and its associated molecular mechanisms using public datasets, clinical samples, human bronchial epithelial cells, and an allergic asthma mouse model. We found that IL-17A was significantly upregulated within serum in asthma cases. Adding IL-17A significantly increased ferroptosis within human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B). In ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic asthmatic mice, IL-17A regulated and activated lipid peroxidation induced ferroptosis, whereas IL-17A knockdown effectively inhibited ferroptosis in vivo by protection of airway epithelial cells via the xCT-GSH-GPX4 antioxidant system and reduced airway inflammation. Mouse mRNA sequencing results indicated that the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) pathway was the differential KEGG pathway in the OVA group compared to healthy controls and the OVA group compared to the IL-17A knockout OVA group. We further used N-acetylcysteine (TNF inhibitor) to inhibit the TNF signaling pathway, which was found to protect BEAS-2B cells from IL-17A induced lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis damage. Our findings reveal a novel mechanism for the suppression of ferroptosis in airway epithelial cells, which may represent a new strategy for the use of IL-17A inhibitors against allergic asthma.

Keywords: Airway inflammation, Asthma, Ferroptosis, Bronchial epithelial cells, Interleukin-17A

Highlights

-

•

The relation of ferroptosis with asthma and the effect of IL-17A on modulating ferroptosis in asthma remain largely unclear.

-

•

Our findings suggest a novel mechanism that IL-17A promotes the development of asthma-associated ferroptosis.

-

•

We find that IL-17A inhibitors reduce airway epithelial ferroptosis and improve inflammation in asthma.

Nomenclature

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- AU

arbitrary units

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Ferr-1

ferrostatin-1

- GSH

glutathione

- PTGS2

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2

- SLC7A11

solute carrier family 7 member 11

- FHC

ferritin heavy chain

- FACL4

fatty acid-CoA ligase 4

- GPX4

glutathione peroxidase 4

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- LPO

lipid peroxide

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- NF-kB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NAC

N-acetyl cysteine

- OVA

ovalbumin

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione

- PAS

periodic acid–Schiff

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- PPI

protein-protein interaction network

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SA

severe drug-resistant asthma

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WGCNA

weighted correlation network analysis

1. Introduction

Asthma is a frequently seen chronic inflammatory airway disorder in children, with the features of recurrent reversible airflow obstruction, airway hyperresponsiveness, airway inflammation, and wheezing [1]. Asthma has a complex etiology involving airway epithelial cell damage, multiple inflammatory cell infiltration, secretion of cytokines, and their interactions [2]. Impaired airway epithelial barrier integrity can be detected within bronchial biopsy samples obtained in adults and children with asthma [3]. A monolayer model of epithelial cell damage in culture also revealed damage repair defects in asthmatic epithelial cells [4]. Thus, airway epithelial damage is a key aspect of asthma pathogenesis and a central point in the progression and acute deterioration of asthma [5]. Exploring the unexplained pathogenesis of asthma in airway epithelial cells is important.

As one of the pro-inflammatory factors generated via activated T cells, interleukin-17A (IL-17A) is associated with several chronic inflammatory diseases, including asthma [6]. Elevated levels of IL-17A were found in sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma cases [7], and IL-17A production was positively correlated with the severity of asthma [8]. Anti-inflammatory steroids such as glucocorticoids are currently recommended for the management of persistent asthma, are highly effective in treating inflammation, and are the preferred therapy for controlling airway inflammation [9]. However, a subset of patients with asthma do not respond to steroid therapy. This is because Th17 cell-mediated airway inflammation is resistant to steroids, and dexamethasone administration suppresses Th2-associated factor generation without affecting IL-17A release [9,10]. Although the Th17/Treg pathways have significant effects on treating allergic disorders [11,12], asthma research has primarily focused on Th2-mediated mechanisms, whereas Th17-related research is relatively rare. Asthma-specific treatments that specifically target IL-17A have not yet been developed.

Ferroptosis is a newly identified type of cell death that contributes to selective clearance of activated cells in specific pathological states [13]. The chronic inflammatory response to numerous respiratory disorders is related to reduced systemic iron contents [14,15]. In addition, lower serum iron levels and exhaled air condensate can be related to pediatric asthma [16,17]. Lung functional impairment is related to the increased ferritin level among normal Korean males, while iron and transferrin saturation levels are not [18]. However, the levels of the oxidative stress marker malondialdehyde (MDA) and plasma iron were significantly higher among asthma cases relative to normal subjects [19,20]. According to various articles, ferroptosis has a critical effect on the asthma pathogenesis, especially the ferroptosis of airway epithelial cells [[21], [22], [23]]. The accumulation of iron in the airway epithelial cells of patients with asthma causes a Fenton reaction and induces ferroptosis, which aggravates the symptoms of asthma [24]. Improved changes were observed in asthma in vivo and in vitro using the ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 (Ferr-1) [13,25]. Acupuncture can reduce IL-17A levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by affecting ferroptosis and oxidative stress [26]. In summary, these findings provide evidence that IL-17A regulates ferroptosis in patients with asthma. However, the mechanism through which IL-17A regulates airway epithelial cell injury in asthma remains unknown. Further clinical and experimental research is warranted for investigating the link of IL-17A with ferroptosis, better understanding the mechanisms involved, and exploring possible new pathways for IL-17A as a therapeutic target in asthma.

The present work focused on examining the levels expression and correlation of IL-17A and ferroptosis-related indicators in asthma patients, asthma sequencing data, and asthma mouse models, as well as the associated enrichment pathways. We then investigated the mechanism by which IL-17A regulated ferroptosis within human bronchial epithelial cells and studied how IL-17A knockdown affected ferroptosis using an asthma mouse model. We aimed to deepen our understanding of the pathogenesis of airway epithelial damage in asthma, provide important targets for asthma treatment selection, and explore new directions for specific drug development.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants and blood serum collection

This study was conducted between March 2021 and August 2021 at the Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children's Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University. The parents of children aged 1–14 years were randomly contacted by the Department of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology and the Department of Children's Health Care to participate in the study.

All parents of children provided informed consent. Participation in the present study was voluntary. The study gained approval from the ethics committees of Second Affiliated Hospital and Yuying Children's Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (LCKY2020-258).

2.2. Public data acquisition and analysis

Microarray datasets GDS4896 and GSE64913 were collected based on the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). We calculated average levels of different probes for the same gene and removed the duplicate probes. Ferroptosis-related genes in this research were acquired based on FerrDb database (http://www.zhounan.org/ferrdb/current/). Differences were expressed using the limma package, taking the log2 transformation, the difference multiplier of large rain 1, the significance threshold of 0.05, the Euclidean distance calculation method, the complete clustering method, and group clustering. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis was performed with ‘enrichKEGG’ in the ‘clusterProfiler’ R package using the gene expression profile prepared above. The GSE198683 dataset was analyzed using the online GEO2R function [27].

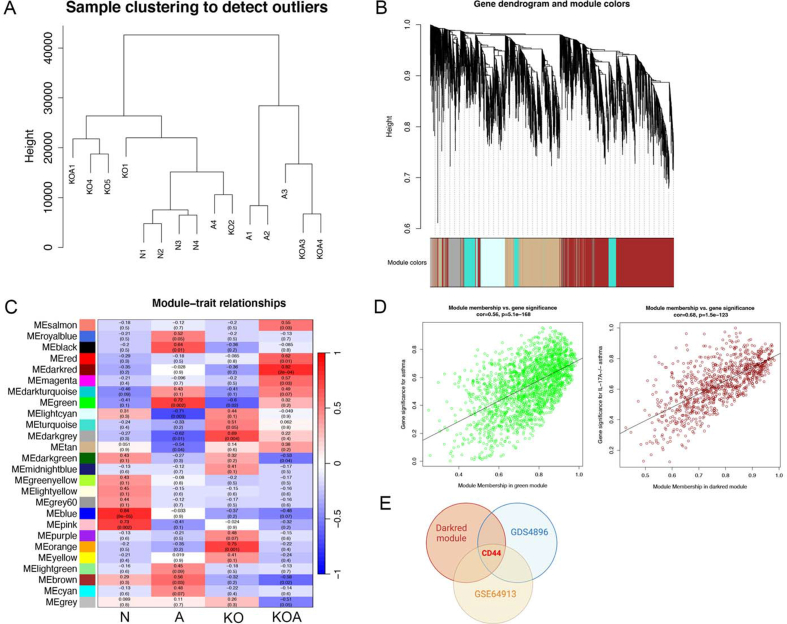

2.3. Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA)

“WGCNA” R package was adopted for weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) to identify highly synergistic variation gene sets and discover candidate genes and co-expressed gene modules associated with disease severity. We removed outliers using sample hierarchical clustering (cut height = 55, minimum size = 10). The weighted adjacency matrix was established using the soft-threshold power, minimum module size and adjacency cutoff of 14, 100 and 0.85; meanwhile, co-expressed gene modules were also detected.

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum IL-5 (Cat #: 88–7056, Invitrogen, USA), IL-13 (Cat #: 88–7439, Invitrogen, USA), and IL-17A (Cat #: 88–7176, Invitrogen, USA) levels in cases and serum IgE (Cat #: 88–50460, Invitrogen, USA), IL-4 (Cat #: 88–7044, Invitrogen, USA), IL-5 (Cat #: 88–7054, Invitrogen, USA), IL-13 (Cat #: 88–7137, Invitrogen, USA), along with IL-17A (Cat #: 88–7371, Invitrogen, USA) in mice were detected through enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

2.5. Cell culture and treatment

We cultured human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B, ATCC) within DMEM (Gibco, USA) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Excell Bio, Shanghai, China) under 37 °C with 5 % CO2. BEAS-2B cells were incubated with erastin (0, 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μM/mL; Cat #: HY-15763, MedChemExpress, USA) and IL-17A (0, 10, 20, 50, and 100 ng/μl; Cat #: C774, Novoprotein, China), separately. Cells exposed to DMSO, erastin (1 μM/mL), and IL-17A (100 ng/μl) treatment for 24 h were respectively set as the control, erastin, and IL-17A groups. In other groups, cells were subjected to 1-h incubation using IL-17A before erastin (1 μM/mL, Cat #: HY-15763, MedChemExpress, USA), ferrostain-1 (Ferr-1, 0.1 μM/mL, Cat #: HY-100579, MedChemExpress, USA), N-Acetyl cysteine (NAC, 1 mM/mL, Cat #: HY-B0215, MedChemExpress, USA), and IL-17A antagonist 1 (Cat #: 2205034-18-8, MedChemExpress, USA) administration.

2.6. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

After BEAS-2B cells were grown overnight in 96-well plates at 1 × 103/well, different additives were added to treat them for 24 h. Then, Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) solution (Cat#: C0039, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Thereafter, absorbance of the 96-well plates was detected with the automatic enzyme standard analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) at 450 nm.

2.7. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) analysis

A reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection kit (Cat #: BL714A, Biosharp, China) that included positive control and 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was utilized to measure total amount of cellular ROS generation. The cells were digested by pancreatic enzyme and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then co-incubated with 1 μM DCFH-DA for 1 h at 37 °C. Lung tissue was ground using a 5-mL syringe plunger and 70-μm filter and digested with IV collagenase (1.5 mg/mL, Cat #: LS00418, Worthington Biochemical Corporation, USA) in 1640 medium without serum (Gibco, USA) for 2 h. The digested tissue was reacted with lung tissue buffer with an equal volume of red blood cell lysis buffer for 2 min, neutralized with a double volume of PBS, centrifuged at 3000 rpm, had the supernatant removed, and resuspended in 1640 medium. DCFH-DA was added according to the ROS assay kit and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. We took 200 μl of the sample and added 2 μl of positive control and incubated for 30 min. Extracellular ROS were removed by re-centrifugation and resuspension with 1640. The FL1-H::FITC-H channel of the flow cytometer was used to detect ROS, and the data were visualized using FlowJo_v10.6.2.

2.8. Animal experiments

We purchased male wild-type C57BL/6 mice from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., and IL-17A ± mice of the C57BL/6 background (3–4 weeks) from Cyagen Biotechnology Co. The gRNAs to mouse Il17a gene, and Cas9 mRNA were co-injected into fertilized mouse eggs to generate targeted knockout offspring. We propagated heterozygotes autonomously and genetically characterized the progeny to obtain stable pure heterozygotes. The primers for identification are in Supplementary Table 1. Mice were allowed to drink water and eat standard food freely and were raised under specific pathogen-free conditions (22 °C ± 1 °C, 50 % ± 5 % humidity) on a light/dark cycle of 12-h/12-h. At one week prior to use, mice were isolated and acclimated. There were forty mice classified into four groups (n = 10 each): Sham, ovalbumin (OVA), IL-17A−/− sham, and IL-17A−/− OVA. Mice in the OVA or IL-17A−/− OVA groups were given intraperitoneal injection of sensitized OVA (100 μg, Cat #: A5503, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as well as aluminum hydroxide (1 mg, Cat #:77161, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) on days 1 and 13. Saline (100 μl) was injected into mice in the Sham and IL-17A−/− sham groups simultaneously. Mice in the OVA or IL-17A−/− OVA groups were administered 1 % OVA in aerosol form for over 30 min for seven consecutive days, while mice in the other two groups were administered saline. All animals were sacrificed within 24 h of the last nebulization. The grouping, sensitization, and treatment processes are shown in Fig. 3A. All experiments were carried out following the ARRIVE guidelines, which gained approval from the Ethics Committee of the Wenzhou Medical University Laboratory Animal Resource Center.

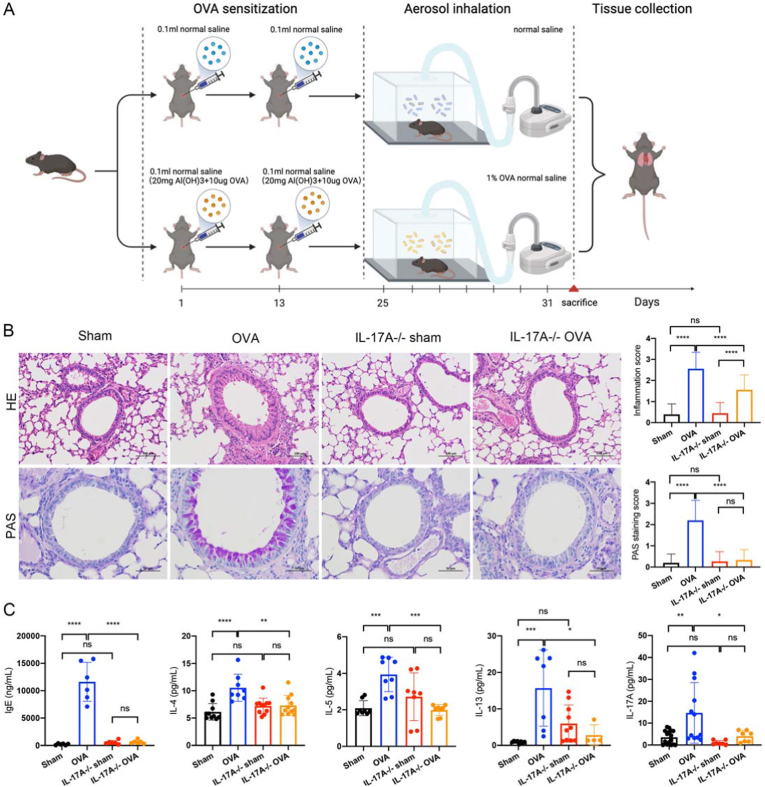

Fig. 3.

IL-17A knockout suppresses asthma-induced lung inflammation. (A) Sketch map showing the construction of the OVA-mediated asthma model used in this study. (B) HE staining (magnification: 200 × , bar = 100 μm) to observe infiltration of perivascular and peribronchial inflammatory cells and PAS staining (magnification: 400 × , bar = 50 μm) to observe mucus production in the epithelial layer in Sham, OVA, IL-17A−/− sham, and IL-17A−/− OVA groups. (D) The mouse serum in the sham and OVA groups. (E) The mouse serum IgE, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17A levels in the four groups. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

2.9. Transcriptome sequencing

Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. performed library construction for eukaryotic high-throughput sequencing of the eukaryotic reference transcriptome from the tested mouse lung tissue samples in this study. MGISEQ-2000 was selected as the sequencing platform for this project.

2.10. Hematoxylin eosin staining, periodic acid-Schiff staining, and Perls Staining

The collected lobe of the left lung of mice was subjected to 24-h fixation using 4 % paraformaldehyde and prepared into lung tissue sections (thickness 5 μm). Peribronchial inflammation was observed through hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections (HE, Cat #: G1120, Solarbio, Beijing, China). Later, sections were stained with Perls Staining (Cat #: G1420, Solarbio, Beijing, China) to visualize iron content and subjected to periodic acid–Schiff (PAS, Cat #: G1285, Solarbio, Beijing, China) staining for identifying mucus-containing cells. The light microscope (Leica, Germany) was utilized to observe tissues and take images after staining (at least five fields of view per slice). According to previous studies [28], we used a semi-quantitative grading method to evaluate the degree of peribronchial inflammation and expressed it as a subjective score from 0 to 4 (normal; 1, few cells; 2, a ring of inflammatory cells 1 cell layer deep; 3, a ring of inflammatory cells 2–4 cells deep; 4, a ring of inflammatory cells of 4 cells deep). PAS-positive cells in the airways were counted using a five-point scale: 0: <0.5 % PAS-positive cells; 1: <25 %; 2: 25–50 %; 3: 50–75 %; and 4: >75 % to evaluate the degree of goblet cell metaplasia in the airway epithelial cells, as previously reported [29]. The data were collected by three independent blinded researchers.

2.11. Transmission electron microscopy

Lung tissues were prepared in 1 × 1 mm sizes before placement into an electron microscope fixative (containing 2.5 % glutaraldehyde, Cat #: G1102, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co.), and gas was removed from the tissues by back-and-forth aspiration using a syringe. The tissue was fixed for a 2-h period under ambient temperature before transfer to a 4 °C refrigerator for overnight fixation. After 2-h fixation with 2 % osmium acid, tissues were dehydrated with gradient acetone, soaked in epoxy resin mixture, and embedded to make ultrathin sections for 30-min uranyl acetate and lead nitrate staining before drying. Finally, images were captured using a Hitachi TEM7700 microscope.

2.12. Fe2+/Fe3+ level

A 20-mg fresh tissue sample was washed once with cold PBS, and 1 mL of assay buffer was added and homogenized. The samples were ultrasonicated for a 5-min period, followed by 10-min centrifugation at 16,000 g for removing insoluble material; then the supernatants were extracted. Iron Assay Kit-Colorimetric (Cat #: I291, Dojindo, Shanghai) was used to detect divalent iron and total iron in mouse lung tissue and patient serum.

2.13. Oxidized glutathione (GSSG)/Glutathione (GSH) ratio measurement

An oxidized glutathione (GSSG)/glutathione (GSH) quantification kit II (Cat #: G263, Dojindo, Shanghai, China) was adopted for measuring tissue and cellular GSH as well as GSSG contents. An automatic enzyme analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was utilized to measure total GSH and GSSG concentrations at 405 nm. This work determined GSH as follows: GSH = Total Glutathione (GSH + GSSG) – GSSG × 2.

2.14. Determination of Fe2+ and lipid peroxide in cells

Fe2+ content was determined with Ferrorange fluorescent probe (Cat #: F374, Dojindo, Shanghai) and lipid peroxide (LPO) levels were detected with Liperfluo fluorescent probe (Cat #: L248, Dojindo, Shanghai). The 35-mm confocal dishes of each group were scanned using laser scanning confocal microscopy. The arbitrary units (AU) of Fe2+ and LPO were determined with ImageJ software for quantifying fluorescence intensity.

2.15. Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) level

An extraction solution (200 μL) was added to 20 mg of the tissue sample and homogenized in an ice bath. After 10-min centrifugation at 8000g and 4 °C, supernatants were removed and placed on ice for measurement. One mL of extracting solution was added to 5 million cells and broken up ultrasonically (power at 200 W, sonication of 3 s, repeated 30 times at 10-s intervals). After 10-min centrifugation at 8000g and 4 °C, supernatants were collected and put on ice prior to measurement. Using the Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) assay kit (Cat #: BC0025, Solarbio, Beijing), the mixture was maintained within the water bath at 100 °C for a 60-min period, followed by cooling in an ice bath and finally 10-min centrifugation at 10,000 g under ambient temperature. Afterwards, absorbance values of samples were determined at 532 and 600 nm after centrifugation for a 10-min period under ambient temperature.

2.16. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

We utilized TRIzol reagent (Cat #: 15596026, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to extract total RNA. Thereafter, a NanoDrop Microvolume Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) was adopted for qualitative and quantitative assessment at 260/280 nm. The TOROIVD®qRT Master Mix (Cat #: RTQ-100, TOROIVD, China) was utilized for reverse transcription. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was later carried out by the fluorescence quantitative PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, USA) with TOROGreen®qPCR Master Mix (Cat #: QST-100, TOROIVD, China). The 2-ΔΔCt approach was utilized to determine relative target gene mRNA levels, while expression was represented by fold change compared with control. Supplementary Table S1 displays primer sequences.

2.17. Western blotting assay

A 12 % sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (Yamei, China) was applied for protein separation; then proteins were transferred on the polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Germany). Next, membranes were subjected to blocking and overnight incubation using primary antibodies of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2, Cat #: ab179800, 1:20000, Abcam), solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11 (xCT), Cat #: 382036, 1:1000, ZENBIO), fatty acid-CoA ligase 4 (FACL4, Cat #: ab155282, 1:20000, Abcam), ferritin heavy chain (FHC, Cat #: R23306, 1:1000, ZENBIO), glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4, Cat #: 381958, 1:1000, ZENBIO), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α, Cat #: AF7014, 1:1000, Affinity Biosciences, China), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB p65, Cat #: AF7014, 1:1000, Affinity Biosciences, China), phospho–NF–kB p65 (Ser536) (Cat #: AF2006, 1:1000, Affinity Biosciences, China), and β-actin (Cat #:4970, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) at 4 °C. Membranes were later rinsed three times using TBST, followed by incubation using goat anti-rabbit IgG (H + L) (Cat #: S0001, 1:5000, Affinity Biosciences, China) or goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) HRP (Cat #: S0002, 1:5000, Affinity Biosciences, China) for 2 h at RT. Thereafter, a chemiluminescence reagent (Cat #: 1705061, Bio-Rad, USA) was utilized for protein band visualization, whereas quantitative signal analysis was carried out using Image-Pro Plus software.

2.18. Statistical analysis

R software (v4.2.1) was employed for sequencing result analysis. Images were statistically analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.2.0. Inter-group variables were compared using Student's t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) plus Tukey's post-hoc test. All results were represented by mean ± standard deviation. All experiments were repeated at least three times. In each figure, P ≥ 0.05, <0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001 stand for non-significant (ns), *, **, ***, and ****, separately. P < 0.05 indicates significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Ferroptosis and Th17 cell differentiation are important pathways among asthma cases

We analyzed sequencing results of children with asthma and healthy children in the GDS4896 dataset and performed a KEGG enrichment analysis. Ferroptosis and Th17 cell differentiation are important pathways among asthma cases relative to those in normal controls in GDS4896 and GSE64913 datasets (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). We screened for differential ferroptosis-related genes of two groups (Supplementary Table S2) and performed a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis of differential ferroptosis-related genes and IL-17A (Fig. 1B). IL-17A was associated with several ferroptosis-related genes, including IL-6, CD44, and PTGS2 at the protein level. We extended the above results through demonstrating that ferroptosis-related gene NOX1 expression was related to up-regulated IL-17A expression in the GSE64913 dataset (Supplementary Fig. 1B). The relative expressions of the differentially expressed ferroptosis-related genes in asthma patients and healthy subjects are shown in Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1C. Ferroptosis-associated differentially expressed genes were acquired in asthma-related dataset GSE4896, and two sets of differentially expressed genes were intersected to obtain PTGS2, SLC40A1, LPCAT3, and MYB (Fig. 1D). These genes are associated with asthma, IL-17A expression, and ferroptosis.

Fig. 1.

Ferroptosis and Th17 cell differentiation are related with asthma. (A) KEGG analysis of patients with asthma compared to healthy controls using the GDS4896 dataset. (B) Relative expressions of differential ferroptosis-related genes of patients with asthma compared to healthy controls using the GDS4896 dataset. (C) PPI networks analysis of differential ferroptosis-related genes in patients with asthma compared to healthy controls using the GDS4896 dataset. (D) Differentially expressed genes associated with ferroptosis obtained in GSE4896 were intersected with differential genes taken from GSE198683. (E) IL-17A mRNA levels were increased in SA compared with the healthy controls in the GDS4896 dataset. (F) IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17A levels in serum samples from patients with asthma and healthy children. (G) Fe2+, Fe3+, Fe2++Fe3+, and Fe2+/Fe3+ levels in serum samples from patients with acute asthma attack and healthy children. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

In the GDS4896 dataset, IL-17A expression levels were elevated in severe drug-resistant asthma (SA) compared to healthy controls (Fig. 1E). A total of 45 children with asthma according to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA 2020, www.ginasthma.org) diagnostic criteria, and 18 healthy children with no personal allergic diseases were included in this study. In our local clinical sample, IL-5, IL-13, as well as IL-17A levels increased within peripheral serum of patients with asthma (Fig. 1F). At the same time, we tested serum irons in children during acute asthma attack and found that the overall level of irons decreased compared to those in normal children, but the Fe2+/Fe3+ ratio was elevated (Fig. 1G).

3.2. IL-17A disrupts iron homeostasis and induces ferroptosis within BEAS-2B cells

To elucidate the effect of IL-17A on inducing ferroptosis in the airway epithelium, we exogenously added the ferroptosis inducers IL-17A and erastin to BEAS-2B cells. Using the CCK8 experiment, we determined the concentration of erastin (1 μM/mL) to use for subsequent experiments (Fig. 2A). The IL-17A mRNA level increased after erastin was added (Fig. 2B). Moreover, IL-17A had an increased effect on MDA levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). In addition, electron microscopy results showed that an increase in the density of the bilayer membrane of BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells and a decrease in the cristae of ferroptosis-like alterations were observed with the addition of IL-17A (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

IL-17A disrupts iron homeostasis and induces ferroptosis in BEAS-2B cells. (A) CCK8 proliferation curve of BEAS-2B cells after addition of different concentrations of erastin. (B) IL-17A mRNA level increased with addition of erastin. (C) The MDA levels increased with increased concentrations of IL-17A. (D) Electron microscopy images of BEAS-2B cell after adding IL-17A. Magnification: 20000 × , bar = 500 μm. (E, F) The Fe2+ (red fluorescence) and LPO (green fluorescence) levels were photographed via confocal microscopy and arbitrary units were counted. (G) The proportion of cellular ROS increased with the addition of IL-17A and erastin. (H) A similar effect was observed for SLC7A11 and GPX4 mRNA levels of erastin and IL-17A. (I) A similar effect was observed for protein xCT and GPX4 of erastin and IL-17A. All experiments were repeated at least three times. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

LPOs and Fe2+ have an important role in enzyme-related redox and lipid metabolism during ferroptosis. BEAS-2B cells were co-stained with ferroOrange (detected Fe2+) together with Liperfluo (detected LPOs) probes, and confocal microscopy images were obtained. Fig. 2E shows that both Fe2+ as well as LPOs existed within cytoplasm. AU of ferroOrange and Liperfluo within BEAS-2B cells dramatically elevated after exogenous supplementation of IL-17A (100 ng/mL) and erastin (1 μM/mL) in comparison with the control group (Fig. 2F).

The KEGG analysis suggested that Th17 cell differentiation and ferroptosis contribute significantly to asthma. To further investigate the effect of IL-17A on iron homeostasis, we investigated whether IL-17A overexpression significantly increased intracellular ROS levels, similar to the effect of erastin (Fig. 2G). IL-17A and erastin both decreased GPX4 and SLC7A11 mRNA expression (Fig. 2H) and reduced glutathione-utilizing enzyme GPX4 and cystine/glutamate antiporter xCT protein expression (Fig. 2I). Collectively, based on the above results, factors related to higher intracellular iron absorption and storage significantly increased in airway epithelial cells after high IL-17A expression.

3.3. Knockdown of IL-17A mitigated OVA-mediated allergic asthma inflammation in mice

To clarify the possible role of IL-17A in treating asthma and its role in the ferroptosis signaling pathway, we generated an allergic asthma model through administration and nebulization of OVA to mice (Fig. 3A). OVA group mice had rich infiltration of perivascular and peribronchial inflammatory cells, accompanied by obvious mucus generation in the epithelial layer, compared to the sham group (Fig. 3B). After IL-17A knockdown, peribronchi and epithelium did not exhibit any significant difference in comparison with the control group. However, mice in the IL-17A−/− OVA group showed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration around the bronchi and blood vessels and reduced mucus production in the epithelium compared to mice in the OVA group (Fig. 3B). Serum IgE, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-17A levels increased in asthma group and decreased after IL-17A knockdown (Fig. 3C).

3.4. IL-17A disrupted iron homeostasis and regulated lipid peroxidation-induced ferroptosis in ovalbumin (OVA)-induced experimental asthma

Next, we determined whether iron levels and related regulators were altered in the OVA-mediated experimental asthma mouse model, similar to that observed in BEAS-2B cells. According to electron microscopic observations, bronchial epithelial cell mitochondria of the asthma group were reduced in size, the density of the bilayer membrane was increased, the outer mitochondrial membrane was wrinkled and ruptured, and the cristae were reduced compared to the sham group. Notably, mitochondria of the IL-17A−/− OVA group showed no significant difference compared with the IL-17A−/− sham group; however, mitochondrial outer membrane rupture increased after IL-17A knockout (Fig. 4A). The OVA group showed increased iron deposition and Fe2+ in the lung tissue compared to the sham group (Fig. 4B). Moreover, IL-17A knockdown decreased Fe2+ in allergic mouse model lung tissue (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of IL-17A regulated iron homeostasis and decreased ferroptosis in the OVA asthma mice model. (A) Electron microscopy images of sham, OVA, IL-17A−/− sham, and IL-17A−/− OVA groups to observe the size and morphology of mitochondria. Magnification: 20,000 × , bar = 500 μm. (B) Perls staining shows Fe3+ in lung tissue. (C) Fe2+, Fe3+, Fe2++Fe3+, and Fe2+/Fe3+ levels in mouse lung tissue. (D) MDA level in lung tissue in the four groups.(E) ROS level in lung tissue by flow cytometry. (F) PTGS2, FACL4, and FHC mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Oxidative phosphorylation was an important KEGG pathway in the IL-17A−/− OVA mouse group compared with the OVA mouse group (Supplementary Fig. 2). IL-17A significantly increased MDA levels (Fig. 4D). In OVA group, ROS levels were elevated in lung tissue. Knockdown of IL-17A decreased the intracellular ROS levels which induced lipid peroxide accumulation, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis (Fig. 4E). qRT-PCR and western blotting confirmed that FACL4 and PTGS2 which were related to increased lipid peroxidation-dependent ferroptosis were upregulated. The primary iron storage factor, FHC, was downregulated in the asthma group. Reversal of corresponding indices were observed in the IL-17A knockout allergic asthma group compared to the OVA group (Fig. 4F and G).

3.5. Inhibition of IL-17A protects airway epithelial cells from ferroptosis via the xCT-GSH-GPX4 antioxidant system and possibly CD44

GSH participates in biological events like ferroptosis and antioxidant activity, which serves as the substrate of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) [30]. As a critical ferroptosis intermediate representing oxidative stress, the GSSG/GSH ratio significantly increased in the OVA group, which was downregulated when IL-17A was knocked down (Fig. 5A). qRT-PCR and western blotting confirmed that GPX4 and SLC7A11 (xCT) were downregulated in the asthma group. IL-17A knockdown reversed the corresponding ferroptosis index (Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of IL-17A protects airway epithelial cells from ferroptosis via the xCT-GSH-GPX4 antioxidant system (A) The GSSG/GSH ratio in four groups. (B) SLC7A11 and GPX4 mRNA levels by qRT-PCR. (C) The xCT- GSH-GPX4 antioxidant system-related protein levels. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

For obtaining the IL-17A co-expression genes, mouse lung tissue assay was conducted with WGCNA R software. The 2 outliers were removed, and 15 samples were used for the follow-up analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3A) and 26 regulatory modules were identified (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Supplementary Fig. 3C displays the relations of modules, IL-17A knockout with asthma, where green and dark-red modules are important for asthma (cor = 0.72) and IL-17A−/− asthma (cor = 0.82) separately. In the green module, asthma phenotypes were significantly related to gene sets (cor = 0.56), and gene sets were significantly related to IL-17A−/− asthma phenotypes (cor = 0.68) (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Furthermore, only CD44 was intersected in the dark-red module genes and GDS4896 and GSE64913 ferroptosis-related differentially expressed genes. The CD24− cells showing CD44 up-regulation secreted IL-17A [31].

3.6. Ferroptosis caused by IL-17A can be inhibited by TNF inhibitor and IL-17A inhibitors

TNF signaling was an important KEGG pathway in both the OVA mouse group compared with the sham mouse group and in the IL-17A−/− OVA mouse group compared with the OVA mouse group (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we further investigated whether IL-17A affects ferroptosis in airway epithelial cells by influencing the TNF signaling pathway. IL-17A, erastin (ferroptosis activator), NAC (ROS inhibitor, also an inhibitor of TNF, inhibits IκB kinases and inhibits TNF-induced NF-κB activation), Ferr-1 (prevents erastin-induced cytoplasmic and lipid ROS accumulation), and IL-17A inhibitor were used for analysis. Fe2+ and LPOs within BEAS-2B cells significantly elevated after exogenous supplementation of IL-17A (100 ng/mL) and erastin (1 μM/mL) in comparison with the control group (Fig. 2F). Meanwhile, the AU of ferroOrange (Fe2+) and Liperfluo (LPOs) decreased significantly after the addition of the NAC, Ferr-1, and the IL-17A inhibitor (Fig. 6B and C).

Fig. 6.

IL-17A disrupted iron homeostasis and induced ferroptosis in BEAS-2B cells. (A–C) The Fe2+ (red fluorescence) and LPO (green fluorescence) levels were photographed via confocal microscopy and arbitrary units were counted. (D) The proportion of cellular ROS increased with the addition of IL-17A and erastin and decreased with the addition of IL-17A inhibitor and NAC. (F) The MDA levels increased with the addition of IL-17A and erastin and decreased with the addition of IL-17A inhibitor and ferroptosis inhibitor NAC. (G) The Western blot result showed that the TNF signaling pathway was effected by IL-17A inhibitor and ferroptosis inhibitor NAC. All experiments were repeated at least three times. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

IL-17A overexpression significantly increased intracellular ROS levels. However, we investigated decreased ROS production after extra addition of NAC and IL-17A inhibitors (Fig. 6D and E). This suggests that IL-17A effectively increases Fe2+ and LPOs contents within cytoplasm, besides, NAC and IL-17A inhibitors can inhibit this effect. Moreover, MDA levels decreased after extra addition of NAC and IL-17A inhibitors (Fig. 6F). Western blotting results showed that NAC and IL-17A inhibitor had the same effect on the pp65/p65 ratio and TNF-α protein expression (Fig. 6G). These results suggest that TNF inhibitors inhibit the ferroptosis response triggered downstream of IL-17A.

Finally, a sketch map was provided to display the effect of IL-17A on the regulation of ferroptosis inallergic asthma airway epithelial cells (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram showing the effect of IL-17A on regulating ferroptosis during asthma.

4. Discussion

A study in 2019 reported that the total incidence of asthma was 4.2 %, equivalent to 45.7 million Chinese adults [32]. Asthma is caused by multiple factors. As iron nutrition affects the immune response, experimental and clinical studies indicate that pulmonary and systemic iron and/or iron regulatory factors are related to asthmatic airway inflammation [33]. Studies have shown that serum iron levels are related to asthma as well as disease severity. Altered iron levels together with iron-related gene levels within the asthma pathway can be related to lung function [24].

We assessed serum iron levels and related cytokine expression in pediatric patients with asthma and healthy children. Previous research reported lower serum iron levels and exhaled air condensate related to pediatric asthma [16,17]. Our findings also confirm that altered serum iron is associated with pediatric asthma. To be specific, decreased extracellular iron contents whereas elevated intracellular iron contents and IL-17A were related to disease severity. Our findings suggest that IL-17A level markedly elevated within airways of patients with clinical asthma together with experimental asthma models, which were related to ferroptosis of airway epithelial cells. These changes may result from the chronic inflammatory response that leads to disease. In this study, iron deposition increase in lungs in OVA-mediated experimental allergic asthma; moreover, such tissues showed elevated IL-17A level, with a decrease in iron deposition after IL-17A knockdown. These results suggest that IL-17A drives asthma pathogenesis and affects iron homeostasis. Based on our data, factors related to elevated intracellular iron absorption and storage like FHC were significantly downregulated within airway epithelial cells after high IL-17A expression, which may explain one of the reasons for the increased cellular/tissue iron instability in patients with asthma.

Inflammation facilitates iron chelation, and iron metabolism can be disrupted during infection and inflammatory diseases [34]. Our PPI results show that IL-6 was highly correlated with IL-17A in asthma and that IL-6 also enhances iron uptake in cells [35]. The antioxidant NAC mitigates IL-17A-mediated lung inflammation through reversing the oxidant-antioxidant balance while attenuating lung IL-6 expression [34]. In a previous study, inflammatory lung diseases which were associated with elevated IL-17A expression may be mitigated via NAC administration [36]. Although IL-17A and TNF-α have their own receptors, it is interesting to note that IL-17A and TNF-α can interact with each other to drive the expression of common inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, G-MCSF, and CXCL-1 [37,38]. In our study, we found that NAC significantly reduced IL-17A-elevated TNF-α levels, which is an important factor in activating ROS. Therefore, we concluded that IL-17A could exacerbate ferroptosis in asthma by promoting TNF-α release, and NAC can inhibit IL-17A induced ferroptosis. In the present study, we explored two specific ferroptosis inhibitors, Fer-1 and NAC. It appears that NAC is more effective than Fer-1 in inhibiting IL-17A-activated ferroptosis. We suggest that this may be due to the direct inhibition of IκB kinases by NAC to suppress TNF-induced NF-κB activation [39]. We also showed that inhibition of IL-17A reduced ROS and MDA levels in cells and/or lung tissue. FACL4 is highly expressed in asthmatic lung tissue, thereby increasing the synthesis of fatty acids and lipid peroxidation substrates, ultimately leading to increased sensitivity of the lung tissue to ferroptosis. We propose that LPO accumulation in asthmatic mice provides the necessary conditions for ferroptosis to occur in the airway epithelium of asthmatic mice. These findings led us to hypothesize that inflammatory activation and lipid peroxidation due to increased lung IL-17A levels has a certain effect on promoting critical ferroptosis features in asthma.

IL-17A is a key regulator of Th17-type asthma and has emerged as a strategic target for treating severe refractory asthma. We discovered that IL-17A and ferroptosis were important in asthma. Our recent study showed the protective role of the ferroptosis-related AKR1C3 gene in airway epithelial cells of asthma [40]. There is growing evidence that IL-17A inhibition can effectively suppress inflammation and oxidative stress, potentially improving steroid-resistant asthma [6]. We demonstrated that IL-17A is an important regulator of ferroptosis in airway epithelial cells, promotes ferroptosis in asthmatic airway inflammation, and that inhibition of IL-17A can protect cells from ferroptosis. IL-17A knockdown protects airway epithelial cells through the xCT-GSH-GPX4 antioxidant system and TNF signaling, leading to the loss of key ferroptosis features in OVA-induced allergic asthma mice, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis and reducing airway inflammation. Furthermore, IL-17A can directly target epithelial cells and induce different antibacterial responses to extracellular pathogens while promoting tissue remodeling [41]. It is urgently necessary to develop the efficient treatment that targets the Th17/IL-17A axis for severe asthma. One phase 2 clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03299686) using anti-IL-17A antibody showed a negative alteration from baseline of Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ) 6 and 7, indicating an improvement in lung function in patients with asthma. However, an alteration from baseline of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of the predicted volume was not significant. Nevertheless, these data provide a basis for the use of biologics targeting IL-17A in asthma treatment and control.

Our study showed that IL-17A promotes ferroptosis in airway epithelial cells. The higher pulmonary IL-17A level promotes the asthma pathogenic ferroptosis-related mechanism and severity, which would be ameliorated after IL-17A knockdown. Because of the paucity of biological samples available from children (this study was limited to blood samples), we could not determine iron contents within airway tissue biopsies or iron-regulated gene expression in cells obtained from bronchoalveolar lavage. Additionally, the sequencing results of three distinct GEO cohorts were used. There are differences in immune characteristics between children and adults, and the dataset used in this study was not exclusively for children. Although our preliminary findings suggest a strong link between IL-17A upregulation in asthmatic airway epithelial cells and ferroptosis, they do not indicate if alterations of iron homeostasis leading to higher cellular iron accumulation are the disease driver or consequence. These are limitations of this study. Nevertheless, our results suggest that more investigations are warranted for analyzing the involvement of IL-17A in the pathogenesis of asthmatic airway epithelial cell ferroptosis and the mechanisms affecting its severity, as well as to explore and test new IL-17A-related targeted therapies.

Asthma management has evolved from a “one size fits all” approach to an individualized approach, treating the patient rather than the disease. This study demonstrates that IL-17A promotes ferroptosis in asthma, providing valuable insights into future ferroptosis-inducing asthma therapies. Our study provides a new experimental basis for the mechanism by which the inhibition of IL-17A can affect ferroptosis while ameliorating inflammation in the treatment of asthma. It highlights the need for clinical trials to assess the potential therapeutic effects of IL-17A inhibitors alone or in combination with ferroptosis inhibitors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. LY23H010003 and Zhejiang Provincial Clinical Research Center for Pediatric Disease.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children involved in our study for the sample serum provided, the contributors to the GEO database platform for providing meaningful datasets, and the mice used in this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2023.102970.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article.

figs1

figs2

figs3

References

- 1.Gaillard E.A., et al. European Respiratory Society clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis of asthma in children aged 5-16 years. Eur. Respir. J. 2021;58(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.04173-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porsbjerg C., et al. Asthma. Lancet. 2023;401(10379):858–873. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loxham M., Davies D.E. Phenotypic and genetic aspects of epithelial barrier function in asthmatic patients. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017;139(6):1736–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iosifidis T., et al. Aberrant cell migration contributes to defective airway epithelial repair in childhood wheeze. JCI Insight. 2020;5(7) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.133125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frey A., et al. More than just a barrier: the immune functions of the airway epithelium in asthma pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:761. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGeachy M.J., Cua D.J., Gaffen S.L. The IL-17 family of cytokines in Health and disease. Immunity. 2019;50(4):892–906. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.!!! INVALID CITATION !!! [vol. 7, 8].

- 8.Chesné J., et al. IL-17 in severe asthma. Where do we stand? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014;190(10):1094–1101. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0859PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes P.J. Corticosteroid resistance in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;131(3):636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinley L., et al. TH17 cells mediate steroid-resistant airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J. Immunol. 2008;181(6):4089–4097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai H., et al. ICS/LABA combined with subcutaneous immunotherapy modulates the Th17/treg imbalance in asthmatic children. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.779072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan X., et al. Fructooligosaccharides protect against OVA-induced food allergy in mice by regulating the Th17/Treg cell balance using tryptophan metabolites. Food Funct. 2021;12(7):3191–3205. doi: 10.1039/d0fo03371e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon S.J., et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kemna E., et al. Time-course analysis of hepcidin, serum iron, and plasma cytokine levels in humans injected with LPS. Blood. 2005;106(5):1864–1866. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei Z., et al. Inhibition of ferroptosis and iron accumulation alleviates pulmonary fibrosis in a bleomycin model. Redox Biol. 2022;57 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eissa S.A., et al. Iron deficiency anemia as a risk factor in childhood asthma. Egypt. J. Chest Dis. Tuberc. 2016;65(4):733–737. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vlašić Ž., et al. Iron and ferritin concentrations in exhaled breath condensate of children with asthma. J. Asthma. 2009;46(1):81–85. doi: 10.1080/02770900802513007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J., et al. Decreased lung function is associated with elevated ferritin but not iron or transferrin saturation in 42,927 healthy Korean men: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kocyigit A., et al. Alterations in plasma essential trace elements selenium, manganese, zinc, copper, and iron concentrations and the possible role of these elements on oxidative status in patients with childhood asthma. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2004;97:31–41. doi: 10.1385/BTER:97:1:31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narula M., et al. Status of lipid peroxidation and plasma iron level in bronchial asthmatic patients. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2007;51(3):289–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao J., et al. PEBP1 acts as a rheostat between prosurvival autophagy and ferroptotic death in asthmatic epithelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117(25):14376–14385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1921618117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagasaki T., et al. 15LO1 dictates glutathione redox changes in asthmatic airway epithelium to worsen type 2 inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 2022;132(1) doi: 10.1172/JCI151685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu W., et al. Role of ferroptosis in lung diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021;14:2079–2090. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S307081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ali M.K., et al. Crucial role for lung iron level and regulation in the pathogenesis and severity of asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2020;55(4) doi: 10.1183/13993003.01340-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang N., Shang Y. Ferrostatin-1 and 3-methyladenine ameliorate ferroptosis in OVA-induced asthma model and in IL-13-challenged BEAS-2B cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/9657933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang W., et al. TMT-based quantitative proteomics reveals suppression of SLC3A2 and ATP1A3 expression contributes to the inhibitory role of acupuncture on airway inflammation in an OVA-induced mouse asthma model. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021;134 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rahmawati S.F., et al. Function-specific IL-17A and dexamethasone interactions in primary human airway epithelial cells. Sci. Rep. 2022;12(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-15393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng Z., et al. Celastrol alleviates airway hyperresponsiveness and inhibits Th17 responses in obese asthmatic mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:49. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim D.I., Song M.K., Lee K. Comparison of asthma phenotypes in OVA-induced mice challenged via inhaled and intranasal routes. BMC Pulm. Med. 2019;19(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-1001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maiorino M., Conrad M., Ursini F. GPx4, lipid peroxidation, and cell death: discoveries, rediscoveries, and open issues. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;29(1):61–74. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sumaria N., et al. Strong TCRγδ signaling prohibits thymic development of IL-17A-secreting γδ T cells. Cell Rep. 2017;19(12):2469–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.05.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang K., et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of asthma in China: a national cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2019;394(10196):407–418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31147-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ali M.K., et al. Role of iron in the pathogenesis of respiratory disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017;88:181–195. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mu Q., et al. The role of iron homeostasis in remodeling immune function and regulating inflammatory disease. Sci. Bull. 2021;66(17):1806–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad S., et al. Regulation of iron uptake in primary culture rat hepatocytes: the role of acute-phase cytokines. Shock. 2014;41(4):337–345. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nadeem A., et al. IL-17A-induced neutrophilic airway inflammation is mediated by oxidant-antioxidant imbalance and inflammatory cytokines in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018;107:1196–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X., et al. Ellipticine blocks synergistic effects of IL-17A and TNF-α in epithelial cells and alleviates severe acute pancreatitis-associated acute lung injury. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020;177 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar P., et al. Intestinal interleukin-17 receptor signaling mediates reciprocal control of the gut microbiota and Autoimmune inflammation. Immunity. 2016;44(3):659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oka S.-i., et al. N-Acetylcysteine suppresses TNF-induced NF-κB activation through inhibition of IκB kinases. FEBS (Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc.) Lett. 2000;472(2):196–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01464-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y., et al. Bioinformatics analysis of ferroptosis-related gene AKR1C3 as a potential biomarker of asthma and its identification in BEAS-2B cells. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023;158 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.106740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pappu R., Rutz S., Ouyang W. Regulation of epithelial immunity by IL-17 family cytokines. Trends Immunol. 2012;33(7):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.