Abstract

Context

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage in which increasing concerns about body image (BI) coincide with the consolidation of dietary habits (DHs). Multiple studies have sought robust associations between BI and DHs to prevent unhealthy behaviors.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the available literature on the association between BI perception (BIP) and/or satisfaction (BIS) and DHs in adolescents.

Data Sources

A search was carried out of 5 electronic databases (PubMed, SciELO, Cochrane, Embase, and PsycInfo) using a combination of keywords (and synonyms) related to adolescence, BI, and diet.

Data Extraction

Data screening, extraction, and quality assessment were performed independently by 2 investigators using the PRISMA and AXIS guidelines.

Data Analysis

Of 2496 articles screened, 30 articles, published in English or Spanish, that evaluated the relationship between BI and DHs in adolescents aged between 10 years and 18 years, were included. A relationship between accurate BI perception in adolescents and healthy DHs was reported in 5 articles (16.2%). A relationship between overestimation of body weight in adolescents and healthy DHs was reported in 4 articles (13.3%). A relationship between underestimation of body weight and unhealthy DHs was reported in 8 articles (26.7%). In addition, 4 articles (13.3%) reported a relationship between BIS and healthy DHs. The desire to gain weight was associated with unhealthy DHs in 3 (10%) of the articles, while the desire to lose weight was related to healthy DHs in 3 (10%) of the articles and to unhealthy DHs in 3 (10%) other articles. There were also gender differences in the relationship between BIP or BIS and DHs.

Conclusion

Adolescents who underestimate their body weight tend to report less healthy DHs than body weight overestimators. Adolescents unsatisfied with their BI and with a drive for thinness frequently engage in DHs linked to losing weight.

Systematic Review Registration

PROSPERO registration no. CRD42020184625.

Keywords: body image perception, body image satisfaction, eating habits, teenagers

INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a transitional stage in development toward adult life that features many significant physical, psychological, and behavioral changes.1,2 This period is characterized by increasing concerns about body image (BI), due to external pressures from peers and family, and such concerns are reinforced by mass media and social stereotypes about ideal body shape.3–10 Adolescence is thus the time when a link may develop between BI and eating habits.11,12

BI is a psychological term related to self-image that predominantly refers to the visual representation of one’s own body shape and size, regardless of their actual body shape and size, that also includes subjective perceptions, feelings, and thoughts, about that representation. BI is thus a multidimensional construct that refers to one’s perceptions of and attitudes toward one’s own physical characteristics. BI can affect behaviors, and a favorable BI is crucial to emotional well-being.6,10,13–15 BI affects the nature and frequency of appearance-referential thoughts, and the extent of cognitive and behavioral investment in one’s appearance; it is linked to self-esteem, interpersonal confidence, eating and exercise behaviors, and other factors that can affect well-being.16 Therefore, BI involves multiple components: the perceptual component (BI perception [BIP]), the attitudinal component (BI satisfaction [BIS]), the cognition component, and the behavioral component.6,10,14,16–19 BIP is defined as the accuracy with which someone perceives their appearance and can estimate their bodily dimensions.6,7,18 BIS represents the discrepancy between an individual’s perceptual and ideal BI.6,7,20

Previous research shows that between 45% and 60% of children and adolescents have an inaccurate BIP.21 Moreover, a recent systematic review revealed that between 44% and 61% of children and adolescents with excess weight were dissatisfied with their own bodies.7

Several terms related to BI are commonly used interchangeably, such as BI distortion, BIP, BI disturbance, negative BI, and BIS; however, there are some differences in meaning between them. Although BI distortion and BIP are interrelated, BI distortion also includes a cognitive and affective component. Similarly, BI disturbance, negative BI, and BI dissatisfaction are associated; however, the former also manifests on a behavioral level, while negative BI is more connected to a negative view of one’s appearance.6 The lack of consensus on how to interpret BI presents a major challenge in the assessment and understanding of how BI shapes diet in adolescents.17,22 Dietary habits (DHs) refer to the individual decisions regarding what, when, how much, and how often different food groups are consumed. These preferences may be influenced by culture, education, socioeconomic background, lifestyle factors, and health status.23–25 DHs have been shown to have a significant impact on health. For instance, a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, or nuts, but which limits saturated fats, dairy products, and ultraprocessed foods, such as the Mediterranean diet, among others, has been proved to prevent non-communicable diseases.25 Several reviews have investigated links between BI and eating disorders and the risk of obesity, but to our knowledge no previous review has focused exclusively on the relationship between BI and DHs in adolescents.7,22,26 Therefore, the aim of the present systematic review was to examine the potential association of BIP and/or BIS with DHs in adolescents.

METHODS

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO network [CRD42020184625] (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/) and was enacted according to the recommendations of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).27 The PRISMA 2020 checklist is presented in Table S1 in the Supporting Information online.

Search strategy

Five electronic databases were used for the search: PubMed, SciELO, Cochrane, Embase, and PsycInfo. The article searches were carried out on February 8, 2022, with no publication date limitation. Searches were performed using a combination of keywords (and synonyms) on adolescents, BI, and diet in the title or abstract or by Medical Subject Heading (MeSH), with the Boolean operators AND and OR. The complete search strategy in each electronic database is described in Table S2 in the Supporting Information online. The research question for this review was defined using Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Study (PICOS) criteria (Table 1). The final question was, “Is there an association between BIP and/or BIS and DHs in adolescents?”

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for inclusion of studies

| Parameter | Criterion |

|---|---|

| Population (P) | Adolescents (with no known health condition) |

| Intervention (I) | Body image perception and/or satisfaction |

| Comparison (C) | Not applicable |

| Outcome (O) | Dietary habits (including dietary patterns or dietary indicators) |

| Study design (S) | Cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort studies |

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the review, articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) report original research carried out on adolescents between the ages of 10 years and 18 years with no known health condition other than overweight or obesity; (2) be published in English, French, or Spanish; (3) have a cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort study design; and (4) assess the association between BI (perception and/or satisfaction) and dietary patterns or DH indicators (for example, food consumption such as daily servings of fruit and vegetables, or frequency of breakfast). Studies meeting the following criteria were excluded: (1) having a stated aim to evaluate the effect of an intervention; (2) assessing the association between BIP or BIS and diet using only energy intake and/or specific nutrient intakes; (3) having a broader age range and not separately describing the results of our target population.

Screening of articles

All titles and abstracts retrieved by the electronic searches were downloaded, and duplicates were removed using the find duplicates tools in Excel, EndNote Reference Manager, and Rayyan QCRI.28 Records were then imported into Rayyan QCRI, where 2 reviewers (P.B. and A.d.C.G.) separately screened all article titles and abstracts and selected those articles meeting the inclusion criteria. After this initial screening, the 2 researchers individually read all the selected publications to agree on the final list of articles to be included in the review. The researchers also assessed the cited references in the selected studies, with the aim of identifying other articles of potential interest for inclusion in the review. Any disagreements during the selection period were resolved through discussion with 2 additional researchers, who independently reviewed the disputed articles (G.S.B. and J.M.F.A.).

Data extraction

Each reviewer (P.B. and A.d.C.G.) was assigned half the articles for data extraction and subsequently double-proofed the data extraction of the other half. To facilitate study comparisons, a table was designed including the standardized information extracted from all the articles: author and year of publication; country and year of study; sample size and the percentage of girls; age range; assessment tools; outcome of BIP, BIS, and DHs; statistical methods; and the main results of the association between BIP and/or BIS and DHs.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias was assessed independently by the 2 main reviewers (P.B. and A.d.C.G.) using the critical Appraisal tool for Cross-sectional Studies (AXIS).29 This tool did not provide a numerical score. Therefore, the authors made a rational judgement about the quality of the studies. Any disagreements during the quality assessment were resolved through discussion and consultation with additional reviewers when necessary.

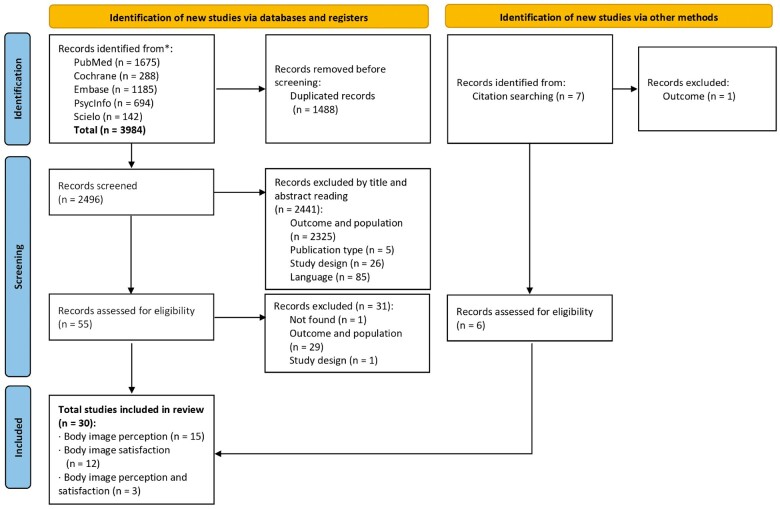

RESULTS

A total of 3984 articles were retrieved from the 5 electronic databases, and 7 additional articles were identified from the cited references. After removing duplicates, 2496 articles were screened. Based on their titles and abstracts, 61 studies were selected for full-text reading to assess for eligibility. Finally, 30 studies were included in the systematic review. The search process and reasons for exclusion are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow-diagram of the literature search process.

All included studies were observational (29 cross-sectional studies and 1 longitudinal cohort study) and published in English (28) or Spanish (2). All of them were published in the last 20 years (11 of them in the last 5 years). Three studies examined the same cohort but differed in the outcome measure30–32 and were analyzed separately. Most articles focused on adolescents in Europe (11 out of 30)30–40 or Asia (11 out of 30),41–51 with the remaining articles examining adolescents in South America (5),52–56 Africa (2),57,58 and the United States (1).59 The focus of 15 articles was the relationship between BIP and DHs,33,35,36,38,39,41–43,45,47,48,51–53,59 12 were about BIS and DHs,30–32,34,44,46,49,50,54–57 and 3 related both BIP and BIS to DHs.37,40,58 Most articles included both boys and girls (26 out of 30), 2 were specific to boys,36,44 and 2 were specific to girls.49,50 A similar majority of articles (26 out of 30) included adolescents with normal weight or overweight/obesity, whereas 2 studies included only adolescents with overweight and obesity,48,59 and another 2 included only adolescents with normal weight.45,54

Body image

For the evaluation of BI, 12 studies used body-shape silhouettes to prompt participants to identify their own perceived body shape, the body shape they considered to be ideal, and the body shape they would like to have. Of these studies, 11 applied previously described scales,30–32,36,48–50,53,56–58 while 1 designed a specific scale for the study.42 Other articles used validated questionnaires (4 out of 30)34,40,48,55 or direct questions (14 out of 30) such as “How satisfied are you with your own body?” or “What do you think about your body weight?”.35,36,38–40,43–47,51,52,54,59 Another 3 articles limited participant responses to the selection among options on a 5-point satisfaction scale.33,41,49 Only 1 article did not describe the specific tool used to evaluate BI.37

Body image perception

BIP classification varied among the studies (Table 2).33,35–43,45,47,48,51–53,58,59 Eleven studies classified BIP as either underestimation, overestimation, or accurate estimation.35–37,41,42,45,47,51–53,58 Six studies categorized adolescents either as having a perceived underweight, perceived accurate, or perceived overweight BI33,38,40,43,48 or as being accurate perceivers versus misperceivers.59 One study referred to BIP as satisfied or dissatisfied.39 Moreover, the analyses used to compare these groups were very diverse, for example comparing differences by weight category, gender, or background.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies on body image perception and dietary habits

| Reference | Country (study years) | Sample size (% girls) | Age rangea | Body image perception assessment | Body image categories | Diet assessment | Dietary outcome | Statistical methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrade et al (2020)52 | Brazil (2009) | 1496 (57.1%) | 11–17 (median: 14.3; IQR: 13.1–15.5) | DQ: How do you feel about your weight? | Underestimation, agreed, overestimation | Validated 97 semiquantitative FFQ |

|

|

|

| Ben Ayed et al (2019)58 | Tunisia (2017–2018) | 1210 (59.7%) | 12–18 (15.6±2.0) | FRS of Stunkard | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation | Eating habits questions | 7 DH indicators (skipping breakfast, frequency of eating vegetables, fruit, pasta, soda, fast food, and eating between meals) |

|

|

| Borda Pérez et al (2016)53 | Colombia (2014) | 262 (38.5%) | 10–13 (11.4±1.1) | FRS of Gardner | Negative distortion (real BMI lower than perceived BMI), positive distortion (real BMI higher than perceived BMI), accurate | Krece Plus questionnaireb | Poor, medium, high adherence to the MedDiet |

|

BI perception was not associated with DHs. |

| Buscemi et al (2018)35 | Italy (2012–2014) | 1643 (46.1%) | 11–16 (12.4±0.7) | DQ: Do you think you are underweight, about the right weight, or overweight? | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation |

|

Poor, medium, high adherence to the MedDiet | Logistic regression model |

|

| Cho et al (2012)41 | Korea (2009) | 631 (44.7%) | 11.57±0.77 | Not described (BI was evaluated by adolescents marking their own body shape as ‘very thin’, ‘somewhat thin’, ‘normal’, ‘somewhat overweight’, and ‘very fat’) | Normal perception and overestimation | 14-item FFQ | 14 food groups |

|

BI perception was not associated with DHs. |

| Edwards et al (2010)59 | United States (2007) | 3687 (42.2%) (adolescents with BMI ≥ 85th percentile) | Not described (9th grade–12th grade) | DQ: How do you describe your weight? | Accurate perception, misperception | DQ: Fruit and vegetable daily intake during the previous 7 days | Eat ≥5 servings of fruit and vegetables per day |

|

Accurate estimation of weight was associated with not meeting the recommended intake of fruit and vegetables. |

| Hernández Camacho et al (2015)36 | Spain (not described) | 87 (0.0%) | 12–18 (13.5±1.5) |

|

Underestimation, accurate, overestimation | Kidmed questionnaire | DH items from Kidmed questionnaire | Chi-square test | BI perception was associated with fast food and vegetable intake. |

| Hsu et al (2016)42 | Taiwan (2006–2007) | 29 313 (48.4%) | 10–18 (not described) | BI figures ad hoc | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation | FFQ | 5 DH indicators (eating breakfast, fruit and vegetable servings, fried foods, soft drinks, night snacks) | Multivariant logistic regression model | Underestimation of weight was related to skipping breakfast and eating fried foods more frequently. |

| Jankauskiene and Baceviciene (2019)37 | Lithuania (not described) | 579 (51.6%) | 14–16 (15.0±0.4) | Not described (body weight perception was assessed as the discrepancy between current self-reported body weight and the reported desire to lose or to gain weight) | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation |

|

|

Kruskal–Wallis test |

|

| Lee and Lee (2016)45 | South Korea (2014) | 20 264 (52.3%) (adolescents with normal weight) | 12–18 (16.4±0.01) | DQ: What do you think of your body image? | Underestimation, correct estimation, overestimation | Eating habits questions |

|

|

|

| Lim and Wang (2013)47 | South Korea (2009) | 72 399 (47.3%) | 12–18 (not described) | DQ: How do you describe your weight? | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation | 8 eating habits questions | 8 DH indicators (frequency of having breakfast, eating fruits, vegetables, milk, sugar sweetened beverages, fast foods) |

|

|

| Marques et al (2018)38 | Portugal (2014) | 3693 (53.4%) | 14–17 (14.7±1.1) | DQ: Do you think your body is…? | Perceived underweight, perceived normal weight, perceived overweight |

|

Realistic negative (reported bad eating practice and eating habits), underestimators (reported good eating practice, but bad eating habits), overestimators (reported bad eating practice, but good eating habits), realistic positive (reported good eating practice and eating habits) |

|

Normal weight perception was related to being realistic positive about diet. |

| Mikkilä et al (2002)39 | Finland (1996–1997) | 60 252 (50.7%) | 14–16 (not described) | DQ: What do you think about your body weight? | Dissatisfaction, satisfactionc |

|

3 dietary patterns (factor analysis): Fast food (hamburgers and hot dogs, meat pasties, pizza, soft drinks sweetened with sugar, crisps, chips, and sweets), Healthy food (fruits and berries, rye bread, fresh vegetables, salad, and yoghurt), and Traditional food (coffee, sweet buns, and sausages) | Logistic regression models | Dissatisfaction was related to less frequently following the Fast food (girls and boys) and the Healthy food (boys) dietary patterns. |

| Niswah et al (2021)48 | Indonesia (2017) | 2144 (48%) (adolescents with overweight and obesity) | 12–18 (not described) |

|

Thin, normal, overweight/obese |

|

5 DH indicators (frequency of snacks, fast food, ready-to-eat meals, sweetened beverages, and fruits) |

|

|

| Oellingrath et al (2015)40 | Norway (2010) | 469 (50.5%) | 12–13 (12.7±0.3) | DQ: How do you consider your current status? | Perceived underweight, perceived accurate, perceived overweight | Modified validated 69-item FFQ (reported by parents) | 4 dietary patterns (PCA): Junk/convenience (high energy processed fast foods, refined grains, cakes and sweets), Varied Norwegian (fruits and vegetables, brown bread, fish, water and regular breakfast and lunch, close to official nutritional advice), Snacking (sugar-rich snack items and drinks, low intakes of vegetables and brown bread, low frequency of breakfast and dinner and high frequency of eating between meals), and Dieting (foods and drinks often associated with weight control, like artificially sweetened drinks and other ‘light’products) | Multivariant logistic regression model | Underweight perception in boys was related to unhealthier DHs (Junk/Convenience dietary pattern). |

| Shirasawa et al (2015)51 | Japan (2005–2009) | 1731 (48.9%) | 12–13 (mean ± sd both boys and girls: 12.3±0.4) | DQ: Do you think you are very thin, thin, normal weight, heavy, or very heavy? | Underestimation, accurate, overestimation | DQ: Snacking after dinner and skipping breakfast | 2 DH indicators (snacking after dinner, skipping breakfast) | Logistic regression model | Overestimation in girls was related to higher consumption of snacks after dinner. |

| Tilles-Tirkkonen et al (2015)33 | Finland (2012–2013) | 887 (52.0%) | 10–17 (not described) | Not described (BI was evaluated from adolescents’ perceptions of their body on a five-point scale ranging from ‘too fat’, through ‘somewhat fat’, ‘appropriate size’, and ‘somewhat thin’ to ‘too thin’) | Somewhat fat or too fat, appropriate size, and somewhat thin or too thin | Eating habits questions | Balanced and imbalanced school lunch eaters |

|

Appropriate perception was related to having a healthier diet (balanced school lunch eaters). |

| Xie et al (2006)43 | China (2002) | 6863 (51.7%) | 14.8±1.7 | DQ: What do you think about your body shape? | Perceived underweight, perceived overweight, misperceived (underweight or overweight) | 5 questions from adapted the US YRBSS questionnaire | 5 DH indicators (frequency of eating vegetables, fruit and fruit juice, meat or poultry, milk and dairy products, and snack foods) | Logistic regression model |

|

Age y.o. (mean ± sd) unless otherwise specified.

The Krece Plus questionnaire was defined but the Kidmed questionnaire was used.

This article misclassified BI perception as satisfaction.

BI, body image; BMI, body mass index; DH, dietary habit; DQ, direct question; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; FRS, figure rating scale; IQR, interquartile range; MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; YRBSS, Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

The reported BI distortion among adolescents varied between 22% and 52%38,39,41,42,45,47,48,51–53,58,59 and was more frequent among boys than girls.35,37,42,45,47,48,51,59 Girls tended to overestimate their body weight more than boys, who tended to underestimate their body weight more often than girls.35,37,40–43,45,47,51,52

In addition, BIP varied between studies according to adolescents’ nutritional status, which showed gender differences. A high percentage of adolescents with underweight, especially girls, tended to overestimate their body weight.39,42,51 Generally, girls with normal weight tended to overestimate their body weight,39,51 whereas boys with normal body weight tended to underestimate it.51 Adolescents with overweight and obesity were more likely to underestimate their body weight.36,42,51

Body image satisfaction

The classification of BIS differed among the analyzed studies (Table 3).30–32,34,37,40,44,46,49,50,54–58 Seven studies classified BIS according to whether adolescents had a desire to lose weight, to gain weight, or were satisfied with their body weight.30–32,37,56–58 Three studies used a score to quantify BIS,34,44,49 and 3 others scored study participants on a range from lower to higher BIS.40,46,55 One study classified BIS as misperception or no misperception.54 Lastly, 1 article did not describe dissatisfaction categories.50 Despite these differences in how BIS was categorized, the results were commonly reported as satisfied versus dissatisfied or as the desire to lose weight versus the desire to gain weight.

Table 3.

Summary of included studies on body image satisfaction and dietary habits

| Author (year of publication) | Country (study years) | Sample size (% girls) | Age rangea | Body image satisfaction assessment | Body satisfaction categories | Diet assessment | Dietary outcome | Statistical methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balluck et al (2016)57 | Mauritius (2014–2015) | 200 (52.0%) | 14–17 (15.5±1.1) | FRS of Stunkard | Desire to gain weight/become thicker, desire to lose weight/become thinner, satisfied | 54-item semiquantitative FFQ |

|

|

Satisfaction was related to higher consumption of fruit. |

| Ben Ayed et al (2019)58 | Tunisia (2017–2018) | 1210 (59.7%) | 12–18 (15.6±2.0) | FRS of Stunkard | Desire to gain weight, desire to lose weight, satisfied | Eating habits questions | 7 DH indicators (skipping breakfast, frequency of eating vegetables, fruit, pasta, soda, fast food, and eating between meals) |

|

|

| Bibiloni et al (2012)30 | Spain (2007–2008) | 1231 (53.4%) | 12–17 (not described) | FRS of Stunkard | Desire for a thicker body, desire for a thinner body, desire to remain the same |

|

2 dietary patterns (factor analysis): Western (yoghurt and cheese, dairy desserts, red meat, poultry, sausages, eggs, bread, cereals, pasta, rice dishes, pizza, fruit juices, canned fruits, nuts, soft drinks, high-fat foods, other oils and fats, sweets, and chocolates) and Mediterranean (yoghurt and cheese, red meat, poultry, fish and seafood, eggs, legumes, pasta, fresh fruit, fruit juices, vegetables, potatoes and tubercles, and olive oil) |

|

Desire to lose weight (boys and girls) and satisfaction (girls) were related to less frequently following the Western dietary pattern. |

| Bibiloni et al (2013)31 | Spain (2007–2008) | 1231 (53.4%) | 12–17 (not described) | FRS of Stunkard | Desire for a thicker body, desire for a thinner body, desire to remain the same |

|

|

|

|

| Bibiloni et al (2016)32 | Spain (2007–2008) | 1231 (53.4%) | 12–17 (not described) | FRS of Stunkard | Desire for a thicker body, desire for a thinner body, desire to remain the same | Kidmed questionnaire |

|

|

Desire to lose weight in boys was associated with poor adherence to MedDiet. |

| Hyun et al (2017)44 | China and South Korea (2011) | 406 (0.0%) | 15–18 (not described) | DQ: How are you satisfied with your own body shape? | Mean satisfaction with BI | 9-item FFQ | DH score (breakfast, fruit, vegetables, protein foods, milk, laver, and kelp intake, and amount and balance of intake during meals) |

|

Satisfaction was positively correlated with DH score. |

| Jankauskiene and Baceviciene (2019)37 | Lithuania (not described) | 579 (51.6%) | 14–16 (15.0±0.4) | Not described (Body Weight Discrepancy was measured as the difference between self-reported body weight, and perceived ideal body weight) | Desire to gain weight, desire to lose weight, satisfied |

|

|

Kruskal–Wallis test |

|

| Lee and Ahn (2007)46 | South Korea (not specified) | 260 (49.6%) | Not described (5th grade) | DQ: How much are you satisfied with your body shape (image)? | Satisfied, neutral, dissatisfied | Eating habits questions | Eating behavior score | ANOVA |

|

| Oellingrath et al (2015)40 | Norway (2010) | 469 (50.5%) | 12–13 (12.7±0.3) | Physical Appearance subscale | Low appearance satisfaction, high appearance satisfaction | Modified validated 69-item FFQ (reported by parents) | 4 dietary patterns (PCA): Junk/convenience (high-energy processed fast foods, refined grains, cakes, and sweets), Varied Norwegian (fruits and vegetables, brown bread, fish, water, and regular breakfast and lunch, close to official nutritional advice), Snacking (sugar-rich snack items and drinks, low intakes of vegetables and brown bread, low frequency of breakfast and dinner, and high frequency of eating between meals), and Dieting (foods and drinks often associated with weight control, like artificially sweetened drinks and other ‘light’ products) | Multivariant logistic regression model |

|

| Ribeiro-Silva et al (2017)55 | Brazil (2009) | 1496 (57.1%) | 11–17 (not described) | Body Shape Questionnaire | Satisfied, slightly dissatisfied, moderately or highly dissatisfied | Validated 97-item FFQ | 3 dietary patterns (factor analysis): Western (sweets and sugars, soft drinks, typical Brazilian dishes pastries, fast food, milk and dairy, oils, beef), Traditional (chicken, fish, eggs, processed meat products, cereals, baked beans), and Vegetarian (granola, roots, vegetables, and fruits)b | Logistic regression model |

|

| Ro and Hyun (2012)49 | China and South Korea (2011–2012) | 448 (100%) | 15–18 (not described) |

|

Mean satisfaction with BI | 9-item FFQ | DH score (breakfast, fruits, vegetables, protein foods, milk, laver, and kelp intake, and amount and balance of intake during meals) |

|

BI satisfaction was significantly related to more desirable DHs. |

| Shaban et al (2016)50 | Kuwait (2015) | 169 (100%) | 10–14 (not described) | FRS of Stunkard (desired BI) | Dissatisfaction categories (not described) | DQ: Do you consider your diet to be healthy? | Healthy, and unhealthy |

|

Dissatisfaction was marginally related to unhealthier DHs. |

| Silva et al (2021)54 | Brazil (2013–2014) | 52 038 (49.8%) (adolescents with normal weight) | 12–17 (14.7) |

|

Misperception (underestimation, overestimation), no misperceptionc | 24-hour dietary recall | 3 dietary patterns (PCA): Traditional Brazilian (rice, beans, vegetables and meat), Processed meat sandwiches and coffee (processed meat, coffee/tea, bread, cheese, oils and fats), and Ultraprocessed and sweet foods (sugar-sweetened beverages, desserts/sweets, and ultraprocessed foods) |

|

|

| Tapia-Serrano et al (2021)34 | Spain (2018–2019) | 2216 (44.2%) | 10–16 (13.1±0.90) | Body Image Dimensional Assessment questionnaire | Mean body dissatisfaction | Kidmed questionnaire | Poor, medium, high adherence to the MedDiet |

|

BI dissatisfaction was associated with better adherence to the MedDiet. |

| Tebar et al (2020)56 | Brazil (not described) | 1074 (55.1%) | 10–17 (13.1±3.5) | Brazilian Silhouettes’ Scale | Desire to gain weight, desire to lose weight, satisfied | Validated FFQ | 6 food groups |

|

|

Age y.o. (mean ± sd) unless otherwise specified.

The authors also defined this dietary pattern as ‘Restrictive,’ considering the food groups associated with this dietary pattern; we decided to use the term ‘Vegetarian.’

This article misclassified BI satisfaction as perception.

BI, body image; DH, dietary habit; DQ, direct question; FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; FRS, figure rating scale; MedDiet, Mediterranean diet; PCA, principal component analysis.

Studies focusing on BI dissatisfaction reported prevalence values of between 19.5% and 77%,30,40,46,50,54–58 with girls being more dissatisfied than boys.30,37,40,54 Girls were more likely to desire to lose weight,30,31,37,54,57,58 whereas boys tended to desire a thicker body.30,31,37,57

Diverse associations were found between BIS and nutritional status. BI dissatisfaction tended to increase with weight.37,40,50 Adolescents with underweight tended to desire a thicker body, while a large majority of adolescents with overweight and obesity desired a thinner figure.31,37,56,57

Dietary habits

DHs were assessed using food-frequency questionnaires (15 studies),30,31,35,37,39–42,44,48,49,52,55–57 24-hour dietary recalls (2 studies),30,54 quality of diet questionnaires (5 studies),32,34–36,53 or direct questions about eating habits (14 studies).31,33,37–39,43,45–48,50,51,58,59 Some studies used more than one dietary assessment tool (7 studies). Six studies derived dietary patterns through statistical methods (principal component analysis,40,54 factor analysis,30,39,55 or cluster analysis52). Only 1 of these derived dietary patterns by gender.30 Most studies (24 out of 30) assessed diet using DH indicators such as number of daily meals, breakfast habit, daily intake of fruit and vegetables,31,36,37,41–43,45,47,48,51,56–59 or indices of diet quality.32–35,38,44,46,49,50,53 One author used both methods (dietary patterns and DH indicators).52

Although the findings regarding adolescent DHs were very heterogeneous, there was a general tendency toward unhealthy behaviors. For instance, fewer than 30% of the adolescents showed good adherence to the Mediterranean diet,32,35,36,53 less than half ate 1 or more portions of vegetables a day, and over 60% consumed fast food weekly.45 The most frequently derived dietary patterns were identified from unhealthier diets, “Western/Fast food/Processed,” to healthier diets, “Traditional,” and “Healthy.”30,39,40,52,54,55 Some studies found gender differences in the consumption of specific food groups such as fruit, meat and poultry, milk and dairy products, and snacks43 or in DH indicators such as the number of meals per day, breakfast frequency, or eating lunch as a family.34,37,54

Body image perception and dietary habits

The studies that explored the relationship between BIP and DHs used highly variable methods and produced highly variable results, the principal characteristics of which are shown in Table 2. Overall, adolescents with an accurate perception and who overestimate their body weight tend to engage more in healthier DHs, while adolescents who underestimate it engage in unhealthier DHs.

An accurate perception of body weight was associated with good eating habits33,38 and a higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet in adolescents with normal weight and overweight; it was, therefore, also associated with meeting more frequently the recommendations of a healthy diet.35 In addition, girls with overweight and obesity who perceived themselves accurately had a lower intake of unhealthy foods48; similarly, boys with an accurate perception of their body weight had higher odds of engaging in a “Healthy food” dietary pattern (fruits and fresh vegetables, rye bread, and yoghurt).39 Nonetheless, some articles reported that accurate perception was related to lower odds of meeting fruit and vegetables intake recommendations, especially among boys,59 and a higher odds of eating fast food.39

Adolescents who underestimated their body weight, both overall and stratified by gender, were found to have unhealthier DHs, with higher odds of skipping breakfast42,47; eating between meals and consuming more fast food, sodas, snacks, and sweets37,40,42,43,45,47,58; and eating less fruit and vegetables.58 Additionally, adolescents who underestimated their body weight also showed a lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet, especially those with normal weight and overweight.35 In contrast, 1 study found that boys who underestimated their body weight had a higher number of meals per day and had breakfast more frequently than accurate body weight perceivers and overestimators.37

Multiple studies related overestimation of body weight to a tendency to report better DHs.43,45,47,58 These adolescents leaned towards reporting a higher intake of vegetables and lower intakes of fast food, sugar-sweetened beverages, and milk,45,47,58 although they were also more often inclined to skip meals (breakfast and dinner).45,58 One study found that girls who overestimated their body weight had a higher consumption of fruits and a lower consumption of milk and dairy products.43 Conversely, overestimator girls were associated with a higher intake of snacks.51

One study reported an association between BIP and fast food and vegetable intake but did not clearly specify the direction of this association.36 Only 3 studies found no association between BIP and diet.41,52,53 Nonetheless, a network analysis in one of these studies showed that, in body-weight overestimation, preferential choices of certain food groups were made.52

Body image satisfaction and dietary habits

The main characteristics, assessment methods, and major results of articles included in the review that explored the relationship between BIS and DHs are summarized in Table 3. Overall, BIS was related to healthy DHs, whereas the desire to gain weight was related to unhealthier DHs. Moreover, both BI dissatisfaction and the desire to lose weight showed conflicting results: adolescents in these groups had both healthy and unhealthy DHs, the latter being mostly related to restrictive diets. One study found that adolescents satisfied with their BI had better DHs than those who were dissatisfied.57 This is in line with another study in which body-satisfied girls had lower odds of following a “Western” dietary pattern, defined by intake of dairy products, meat, canned fruit, fast food, high-fat foods, and sweets and chocolates.30 Similarly, in other studies, comparison of BIS between cohorts from different countries revealed a significant positive correlation between body-satisfied adolescents and higher DH scores (higher intake of breakfast, fruit, vegetables, protein-rich foods, milk, a higher food quantity intake during meals, and more balanced meals).44,49

While some studies reported a relationship between body dissatisfaction and unhealthy DHs,50,54 others linked body dissatisfaction to healthier habits. Body dissatisfaction was related to better adherence to the Mediterranean diet34 and to “Vegetarian” (granola, roots, vegetables, fruit) and “Dieting” (light products) dietary patterns.40,55 In contrast, body-dissatisfied adolescents also tended to have fewer meals per day.37 These associations were also found for body-dissatisfied girls, who had less healthy and more restrictive DHs.40,46

Only 3 studies found a significant relationship between the desire to gain weight and an unhealthy diet, with these adolescents reporting a lower consumption of fruit and vegetables56,58; more frequent skipping of breakfast, snacking, and fast-food consumption54,58; and a higher intake of sweets54,56 than their body-satisfied counterparts. No study reported an association between the desire to gain weight and a healthy diet.

Studies showed different trends regarding the association between the desire to lose weight and diet. Adolescents who desired to lose weight consumed fewer sodas and less fast food than body-satisfied adolescents, and had lower odds of snacking58 or engaging in a “Western” dietary pattern (dairy products, meat, canned fruit, fast food, high-fat foods, and sweets and chocolates).30 Nevertheless, 1 study also showed that adolescents desiring to lose weight ate less fruit and vegetables,56 in line with another study in which the desire to lose weight among normal-weight adolescents was less associated with a healthy dietary pattern (“Traditional Brazilian” defined by rice, beans, vegetables, and meat).54 In particular, girls desiring to lose weight tended to avoid the “Processed meat sandwiches and coffee” (processed meat, coffee/tea, bread, cheese, oils and fats), and “Ultraprocessed and sweet foods” (sugar-sweetened beverages, desserts/sweets, and ultraprocessed foods) as unhealthier dietary patterns,54 whereas boys desiring to lose weight reported a lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet.32 In adolescents with excess weight, the desire to be thinner was related to healthier DHs than those seen among body-satisfied adolescents with normal weight and body-satisfied boys with excess weight.31 Regarding breakfast habits, 2 studies found that girls with a drive for thinness skipped breakfast more frequently,31,37 while 1 study reported that adolescents who desired to lose weight had a lesser tendency to skip breakfast.58

Quality assessment

Details of the quality of each study are shown in Table S3 in the Supporting Information online. In general, the quality of studies was medium to good, with a mean 73% compliance with the assessment criteria. Some internal discrepancies between the results reported in the tables and those reported in the main text were found in a few studies.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review included 30 studies that assessed the relationship between BIP and/or BIS and different DH characteristics in adolescents between the ages of 10 years and 18 years. The majority of the articles used silhouette scales or direct questions to evaluate BI, and most of them assessed diet using food-frequency questionnaires or specific questions concerning DHs. In this systematic review, we focused exclusively on DHs rather than energy intake or the nutritional quality of the diet, since the behaviors and habits that revolve around diet transcend nutrient content. The results of our analysis are somewhat heterogeneous, in line with the results of a recent systematic review on BI, unhealthy eating, and physical activity.22

Body image perception and dietary habits

The evidence gathered in this review indicated that accurate perception of body weight is related to healthy eating behaviors and higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet.33,35,38,39,48 This finding is in line with the findings of other studies, in which children who misperceived their body weight were more likely to have unhealthy dietary patterns.60 In contrast, other articles included in the present review concluded that adolescents who perceived their body weight accurately less frequently achieved the recommended intake of fruit and vegetables or had higher odds of following an unhealthy dietary pattern (hamburgers, hot dogs, meat pasties, pizza, sweetened beverages, chips and sweets) than misperceivers.39,59 This conclusion was supported by evidence that children who misperceived their body weight were more likely to have a healthier diet (consuming fewer dairy products, sugar-sweetened beverages, sweets, and salty snacks) than accurate perceivers.21 This difference may be due to adolescents who underestimate their body weight being unaware of their excess weight and therefore unconcerned about engaging in unhealthy habits,61 whereas overestimating adolescents may take more care of their eating habits in order to reduce the perceived excess weight. In this regard, a few articles showed that children and adolescents who underestimate their body weight lean towards unhealthier eating habits, with higher consumption of high-calorie meals37,40,42,43,45,47 and lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet,35 and lower consumption of fruit and vegetables.58 This might be because these children have a lower sense of having excess weight and are therefore less motivated to engage in controlling their diet and taking action to lose weight.60,61 These behaviors might also be triggered by the social misconception that being below or at normal weight implies not having to worry about eating healthily. For the most part, overestimating adolescents have been reported as engaging in healthy eating habits such as eating more vegetables and less fast food and sugar-sweetened beverages.45,47,58 Another study found that overestimating adolescents tend to eat more fruit and vegetables and less fast food.21 There is also evidence that overestimating adolescents have more restrictive habits, such as more frequently skipping breakfast or dinner,45,58 which is in line with the wider literature. For instance, a Chinese study reported that participants who overestimated their body weight tended to engage in a “Malnourished” dietary pattern (lower intake of vegetables, fruits, drinking milk, snacks, fast food, and fries, and more frequent breakfast skipping),60 and a Japanese study reported that girls who overestimated their body weight reported not eating breakfast on a daily basis.11 Adolescents who have a sense of having excess weight may tend to engage into activities that they relate to losing weight, which can be healthy (such as healthy DHs and regular physical activity) or unhealthy (restrictive eating habits and extreme physical activity).7,62,63

Body image satisfaction and dietary habits

The literature suggests an association between healthy BIS and DHs, but no clear evidence has been found for an association between BI dissatisfaction and DHs. Most studies in this review showed that adolescents who are satisfied with their BI have healthier eating behaviors,44,49 such as eating more fruit and vegetables57 or, for girls, having lower odds of following a “Western” dietary pattern (dairy products, high fat and sugar foods and drinks, red meat, poultry, cereals, pasta, rice dishes).30 Likewise, some studies stated that body dissatisfaction is related to unhealthier DHs (mainly eating fewer meals)37,50,54; however, others linked dissatisfaction to better adherence to the Mediterranean diet or to eating more fruit and vegetables.34,55 These findings agree with a Swiss study that linked body dissatisfaction in adolescents to a higher intake of fruit and vegetables and more frequent skipping of breakfast.64 Although these behaviors can appear contradictory, both are socially associated with losing weight, in a healthy or unhealthy way. This mixed pattern is also supported by the current analysis, with some of the articles included in the review showing associations between a desire to lose weight and healthier DHs and a low frequency of skipping breakfast,30,31,58 whereas others reported the opposite association, with low adherence to the Mediterranean diet,32 restrictive behaviors like skipping breakfast more frequently,31,37 or lower consumption of fruit and vegetables.56 No article in the review sample showed an association between the desire to gain weight and a healthy diet; instead, articles in the review found that adolescents seeking to gain weight tend to eat less fruit and more sweets, snacks, and fast food.56,58 This behavior might be based on a belief that eating high-energy foods would lead to weight gain.

Body image, dietary habits, and gender

The surveyed articles consistently show that girls and boys with accurate BIP or who are satisfied with their body weight engage in healthier eating behaviors,30,39,44,49,50 and girls and boys who underestimate their body weight engage in unhealthier behaviors.37,40,43 However, girls who overestimate their body weight or want to lose weight tend to eat more fruit and fewer dairy products and snacks48 and processed foods,54 and to skip breakfast more often.31,37 This pattern is not common among overestimating boys, who tend to engage in healthier DHs31 or have a lower adherence to the Mediterranean diet.32 In addition, boys usually underestimate their body weight, whereas girls overestimate it,35,37,40–42,45,47,51,52,58 and girls tend to be more body-dissatisfied and to desire to decrease their body weight, whereas boys want to increase it.37,40 This divergence might reflect social pressures related to current ideal body types, with girls leaning towards thinner body shapes and therefore engaging in what they perceive as weight-reducing behaviors, whereas boys would prefer to have a muscular body.42,65

The results obtained in this review reveal a high prevalence among adolescents of misperception or dissatisfaction with body weight, accompanied by a tendency to engage in unhealthy or restrictive DHs. It is particularly important to address this issue, as unhealthy habits can lead to the development of eating disorders.16 Previous studies have claimed that BI distortion and dissatisfaction can increase the risk of developing unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, such as excessive physical activity,66,67 and have emphasized the need for strategies to prevent these behaviors.67,68 The development of a healthy lifestyle is known to depend on effective health promotion from childhood.69 In addition to the established components of diet and physical activity, health-promotion strategies should also include emotion management. Self-esteem plays an essential role in BI, acting as a protective factor in the association between body mass index and BIP and BIS.6,70 Accumulated research shows the importance of training children and adolescents in healthy habits through programs that aim to disprove myths about diet and physical activity and promote appropriate emotion management.6,9 Schools and families are the most suitable environments in which to implement health-education programs that encourage healthy choices and positive attitudes towards health and self-care.13,69,71,72

Limitations and strengths

There are some limitations to this systematic review. First among these is the lack of consensus on how to define BI, with different articles using the same scale with different interpretations, thus complicating synthesis of their results. It further appears that 1 study may have mistakenly classified BIP as satisfied or dissatisfied, while another framed BIS as misperception versus no misperception.39,54 A second limitation is that several studies showed inconsistencies between the results shown in the tables and those presented in the text, making it difficult to know what conclusions to extract. Although no tool has been demonstrated to be superior to the others, another limitation is the diversity of instruments and statistical methods used to relate BI and DHs, which made comparison difficult. Likewise, the variety of tools (food-frequency questionnaire, 24-hour recall, quality questionnaires) and statistical techniques (cluster analysis, principal component analysis, etc.) used to assess diet was an additional difficulty due to the heterogeneity of DHs derived. Additionally, the review only included studies that measured diet as an indicator or as dietary patterns, and therefore studies that examined the relationship between BIP or BIS, and energy, micro-, and macro-nutrient intake were excluded. Furthermore, the lack of longitudinal studies impeded the determination of cause and effect in the relationship between BIP and/or BIS and DHs. Finally, the search was limited to articles in English, French, and Spanish, and hence additional studies in other languages may have been overlooked. Due to the great heterogeneity in the description of the association between BIP and/or BIS and DHs in the studies included in this review, it was not possible to carry out a meta-analysis.

A strength of this analysis is that it is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review to exclusively study the relationship between BI and DHs in adolescents. The review also marks an important step towards clarifying the definitions of and differences between BIP and BIS, helping to set the ground for future studies of the links between BIP and BIS and DHs.

CONCLUSION

Despite the heterogeneity of the results, adolescents who underestimate their body weight tend to report unhealthier DHs, while those overestimating or accurately perceiving their body weight lean toward a healthier diet. Moreover, adolescents with a desire to gain weight have unhealthier DHs, while those with a drive for thinness engage in either healthy or unhealthy habits associated with weight loss. Differences in BI and DHs by gender generally reflect a desire among girls for a thinner body and among boys for a thicker one.

These results highlight the need to carry out intervention programs on BI, taking into account gender, socioeconomic, and cultural perspectives in order to fight stereotypes and misbeliefs that might lead adolescents to unhealthy habits, such as restrictive diets or extreme physical activity. In addition, further longitudinal studies may help better understand and quantify the association between BIP and/or BIS and DHs over time by using harmonized methods to help clarify the heterogeneity of the results.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Miriam Arnau, who collaborated in the data extraction phase, and Simon Bartlett (CNIC), who provided English editing.

Author contributions. P.B., A.d.C.G., and L.A.M. conceived the overall study. P.B. and A.d.C.G. were the main reviewers and performed the screening and data collection. G.S.B. and J.M.F.A. assisted as independent reviewers. G.S.B., J.M.F.A., R.F.J., and L.A.M. provided scientific support over the course of this work. P.B. and A.d.C.G. drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the published version.

Funding. The study was supported by the SHE Foundation—“la Caixa” Foundation under agreement LCF/PR/CE16/10700001. G.S.B. is the recipient of grant LCF/PR/MS19/12220001 funded by “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434). Support was also provided by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN) (grant AGL2016–75329‐R). R.F.-J. is the recipient of grants PI19/01704 and PI22/01560 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria—Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund “A way to make Europe”/“Investing in your future”. The CNIC is supported by the ISCIII, the MCIN, and the Pro CNIC Foundation, and is a Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence (grant CEX2020-001041-S funded by MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Contributor Information

Patricia Bodega, Foundation for Science, Health, and Education (SHE), Barcelona, Spain; Cardiovascular Health and Imaging Lab, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Madrid, Spain.

Amaya de Cos-Gandoy, Foundation for Science, Health, and Education (SHE), Barcelona, Spain; Cardiovascular Health and Imaging Lab, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Madrid, Spain.

Juan M Fernández-Alvira, Cardiovascular Health and Imaging Lab, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Madrid, Spain.

Rodrigo Fernández-Jiménez, Cardiovascular Health and Imaging Lab, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC), Madrid, Spain; Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica En Red en enfermedades CardioVasculares (CIBERCV), Madrid, Spain.

Luis A Moreno, GENUD (Growth, Exercise, NUtrition and Development) Research Group, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Instituto Agroalimentario de Aragón (IA2) and Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria Aragón (IIS Aragón), Zaragoza, Spain; Consorcio CIBER, M.P. Fisiopatología de la Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERObn), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Madrid, Spain.

Gloria Santos-Beneit, Foundation for Science, Health, and Education (SHE), Barcelona, Spain; The Zena and Michael A. Wiener Cardiovascular Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York, USA.

Supporting Information

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

Table S1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 checklist

Table S2 Search strategy

Table S3 Quality of the studies included in the systematic review assessed by AXIS tool

REFERENCES

- 1. Jaworska N, MacQueen G.. Adolescence as a unique developmental period. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2015;40:291–293. doi: 10.1503/jpn.150268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pringle J, Mills K, McAteer J, et al. A systematic review of adolescent physiological development and its relationship with health-related behaviour: a protocol. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0173-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deschamps V, Salanave B, Chan-Chee C, et al. Body-weight perception and related preoccupations in a large national sample of adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2015;10:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dewi RC, Wirjatmadi B.. Energy intake, body image, physical activity and nutritional status of teenagers. J Public Health Afr. 2019;10:s1. doi: 10.4081/jphia.2019.1194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goonapienuwala BL, Agampodi SB, Kalupahana NS, et al. Body image perception and body dissatisfaction among rural Sri Lankan adolescents; do they have a better understanding about their weight? Ceylon Med J. 2019;64:82–90. doi: 10.4038/cmj.v64i3.8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hosseini SA, Padhy RK.. Body Image Distortion. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jiménez-Flores P, Jiménez-Cruz A, Bacardi-Gascon M.. Insatisfacción con la imagen corporal en niños y adolescentes: revisión sistemática. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2017;34:479–489. doi: 10.20960/nh.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khor GL, Zalilah MS, Phan YY, et al. Perceptions of body image among Malaysian male and female adolescents. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:303–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. O’Dea JA, Abraham S.. Improving the body image, eating attitudes, and behaviors of young male and female adolescents: a new educational approach that focuses on self-esteem. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:43–57. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Voelker D, Reel J, Greenleaf C.. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: current perspectives. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2015;6:149–158. doi: 10.2147/ahmt.s68344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mori K, Sekine M, Yamagami T, et al. Relationship between body image and lifestyle factors in Japanese adolescent girls. Pediatr Int. 2009;51:507–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Emmons L. Predisposing factors differentiating adolescent dieters and nondieters. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:725–731. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)91937-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, et al. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people: health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. 2012. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/326406. Accessed April 27, 2022.

- 14. Millstein RA, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, et al. Relationships between body size satisfaction and weight control practices among US adults. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:119–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahim NNA, Chin YS, Sulaiman N.. Socio-demographic factors and body image perception are associated with BMI-for-age among children living in welfare homes in Selangor, Malaysia. Nutrients. 2019;11:142. doi: 10.3390/nu11010142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cash TF, Fleming EC.. The impact of body image experiences: development of the body image quality of life inventory. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31:455–460. doi: 10.1002/eat.10033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pallan MJ, Hiam LC, Duda JL, et al. Body image, body dissatisfaction and weight status in south Asian children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yamamotova A, Bulant J, Bocek V, et al. Dissatisfaction with own body makes patients with eating disorders more sensitive to pain. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1667–1675. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S133425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cash TF. Body-image attitudes: evaluation, investment, and affect. Percept Mot Skills. 1994;78:1168–1170. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.78.3c.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silva D, Ferriani L, Viana MC.. Depression, anthropometric parameters, and body image in adults: a systematic review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2019;65:731–738. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.65.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Angoorani P, Heshmat R, Ejtahed HS, et al. Body weight misperception and health-related factors among Iranian children and adolescents: the CASPIAN-V study. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017;30:1033–1040. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2017-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duarte LS, Palombo CNT, Solis-Cordero K, et al. The association between body weight dissatisfaction with unhealthy eating behaviors and lack of physical activity in adolescents: a systematic review. J Child Health Care. 2021;25:44–68. doi: 10.1177/1367493520904914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krause D, Margetts C, Roupas P.. Whole of diet approaches: evaluating the evidence for healthy policy guidelines, the Mediterranean, vegetarian, paleolithic, Okinawa, ketogenic, and caloric-restrictive diets on the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. In: Martin CR, Preedy VR, eds.. Diet and Nutrition in Dementia and Cognitive Decline. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2015:253–263. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407824-6.00024-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Féart C, Samieri C, Allès B, et al. Potential benefits of adherence to the Mediterranean diet on cognitive health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;72:140–152. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112002959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Romero-Robles MA, Ccami-Bernal F, Ortiz-Benique ZN, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet associated with health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: a systematic review. BMC Nutr. 2022;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40795-022-00549-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flynn KJ, Fitzgibbon M.. Body images and obesity risk among black females: a review of the literature. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20:13–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02893804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM,. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011458. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bibiloni MdM, Martínez E, Llull R, et al. Western and Mediterranean dietary patterns among Balearic Islands’ adolescents: socio-economic and lifestyle determinants. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:683–692. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bibiloni MDM, Pich J, Pons A, et al. Body image and eating patterns among adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bibiloni MDM, Pons A, Tur JA.. Compliance with the Mediterranean Diet Quality Index (KIDMED) among Balearic Islands’ adolescents and its association with socioeconomic, anthropometric and lifestyle factors. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;68:42–50. doi: 10.1159/000442302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tilles-Tirkkonen T, Suominen S, Liukkonen J, et al. Determinants of a regular intake of a nutritionally balanced school lunch among 10–17-year-old schoolchildren with special reference to sense of coherence. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28:56–63. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tapia-Serrano MA, Molina-López J, Sánchez-Oliva D, et al. Mediating effect of fitness and fatness on the association between lifestyle and body dissatisfaction in Spanish youth. Physiol Behav. 2021;232:113340. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buscemi S, Marventano S, Castellano S, et al. Role of anthropometric factors, self-perception, and diet on weight misperception among young adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Eat Weight Disord. 2018;23:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hernández Camacho JD, Rodríguez Lazo M, Bolaños Ríos P, et al. Hábitos alimentarios, sobrecarga ponderal y autopercepción del peso en el ámbito escolar. Nutr Hosp. 2015;32:1334–1343. doi: 10.3305/nh.2015.32.3.9351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jankauskiene R, Baceviciene M.. Body image concerns and body weight overestimation do not promote healthy behaviour: evidence from adolescents in Lithuania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:864. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marques A, Naia A, Branquinho C, et al. Adolescents’ eating behaviors and its relationship with family meals, body mass index and body weight perception. Nutr Hosp. 2018;35:550–556. doi: 10.20960/nh.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mikkilä V, Lahti-Koski M, Pietinen P, et al. Associates of obesity and weight dissatisfaction among Finnish adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2003;6:49–56. doi: 10.1079/phn2002352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Oellingrath IM, Hestetun I, Svendsen MV.. Gender-specific association of weight perception and appearance satisfaction with slimming attempts and eating patterns in a sample of young Norwegian adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:265–274. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cho JH, Han SN, Kim JH, et al. Body image distortion in fifth and sixth grade students may lead to stress, depression, and undesirable dieting behavior. Nutr Res Pract. 2012;6:175–181. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2012.6.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hsu YW, Liou TH, Liou YM, et al. Measurements and profiles of body weight misperceptions among Taiwanese teenagers: a national survey. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25:108–117. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2016.25.2.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xie B, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D, et al. Weight perception and weight-related sociocultural and behavioral factors in Chinese adolescents. Prev Med. 2006;42:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hyun H, Lee H, Ro Y, et al. Body image, weight management behavior, nutritional knowledge and dietary habits in high school boys in Korea and China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26:923–930. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.122016.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee J, Lee Y.. The association of body image distortion with weight control behaviors, diet behaviors, physical activity, sadness, and suicidal ideation among Korean high school students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:39. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2703-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee S, Ahn H-S.. Relation of obesity-related attitudes, knowledge, and eating behaviors with body weight and body shape satisfaction in 5th-grade Korean children. Nutr Res Pract. 2007;1:126–130. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2007.1.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lim H, Wang Y.. Body weight misperception patterns and their association with health-related factors among adolescents in South Korea. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:2596–2603. doi: 10.1002/oby.20361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Niswah I, Rah JH, Roshita A.. The association of body image perception with dietary and physical activity behaviors among adolescents in Indonesia. Food Nutr Bull. 2021;42:S109–S121. doi: 10.1177/0379572120977452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ro Y, Hyun W.. Comparative study on body shape satisfaction and body weight control between Korean and Chinese female high school students. Nutr Res Pract. 2012;6:334–339. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2012.6.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shaban LH, Vaccaro JA, Sukhram SD, et al. Perceived body image, eating behavior, and sedentary activities and body mass index categories in Kuwaiti female adolescents. Int J Pediatr. 2016;2016:1092819. doi: 10.1155/2016/1092819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shirasawa T, Ochiai H, Nanri H, et al. The relationship between distorted body image and lifestyle among Japanese adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Public Health. 2015;73:32. doi: 10.1186/s13690-015-0082-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Andrade VMB, de Santana MLP, Fukutani KF, et al. Systems nutrology of adolescents with divergence between measured and perceived weight uncovers a distinctive profile defined by inverse relationships of food consumption. Nutrients. 2020;12:1670–1670. doi: 10.3390/nu12061670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Borda-Pérez M, Alonso Santos M, Martínez Granados H, et al. Percepción de la imagen corporal y su relación con el estado nutricional y emocional en escolares de 10 a 13 años de tres escuelas en Barranquilla (Colombia). Salud Uninorte Barranquilla. 2016;32:472–482. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Silva S, Alves M, Vasconcelos F, et al. Association between body weight misperception and dietary patterns in Brazilian adolescents: cross-sectional study using ERICA data. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257603. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ribeiro-Silva RC, Fiaccone RL, Conceição-Machado ME, et al. Body image dissatisfaction and dietary patterns according to nutritional status in adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2018;94:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tebar WR, Gil FCS, Scarabottolo CC, et al. Body size dissatisfaction associated with dietary pattern, overweight, and physical activity in adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22:749–757. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Balluck G, Toorabally BZ, Hosenally M.. Association between body image dissatisfaction and body mass index, eating habits and weight control practices among Mauritian adolescents. Malays J Nutr. 2016;22:389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ben Ayed H, Yaich S, Ben Jemaa M, et al. What are the correlates of body image distortion and dissatisfaction among school-adolescents? Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019;33:5. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2018-0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Edwards NM, Pettingell S, Borowsky IW.. Where perception meets reality: self-perception of weight in overweight adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e452–e458. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Qin T-T, Xiong H-G, Yan M-M, et al. Body weight misperception and weight disorders among Chinese children and adolescents: a latent class analysis. Curr Med Sci. 2019;39:852–862. doi: 10.1007/s11596-019-2116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Duncan DT, Wolin KY, Scharoun-Lee M, et al. Does perception equal reality? Weight misperception in relation to weight-related attitudes and behaviors among overweight and obese US adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pasch KE, Klein EG, Laska MN, et al. Weight misperception and health risk behaviors among early adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2011;35:797–806. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.35.6.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jáuregui-Lobera I, Ezquerra-Cabrera M, Carbonero-Carreño R, et al. Weight misperception, self-reported physical fitness, dieting and some psychological variables as risk factors for eating disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5:4486–4502. doi: 10.3390/nu5114486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Jaeger I. Habitudes alimentaires et image corporelle chez des étudiants de deuxième année de gymnase à Lausanne. Revue Médicale Suisse. 2008;4:1432–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Acosta MN, Díaz de León C, Gómez Tello BL, et al. Percepción de la imagen corporal, consumo de alimentos y actividad física en estudiantes de un colegio de bachilleres. Rev Esp Nutr Comunitaria. 2006;12:100–107. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bašková M, Holubčíková J, Baška T.. Body-image dissatisfaction and weight-control behaviour in Slovak adolescents. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2017;25:216–221. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chisuwa N, O’Dea JA.. Body image and eating disorders amongst Japanese adolescents. A review of the literature. Appetite. 2010;54:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jáuregui Lobera I, Romero Candau J, Bolaños Ríos P, et al. Conducta alimentaria e imagen corporal en una muestra de adolescentes de Sevilla. Nutr Hosp. 2009;24:568–573. doi: 10.3305/nh.2009.24.5.4486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Santos-Beneit G, Fernández-Jiménez R, de Cos-Gandoy A, et al. Lessons learned from 10 years of preschool intervention for health promotion: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:283–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ahadzadeh AS, Rafik-Galea S, Alavi M, et al. Relationship between body mass index, body image, and fear of negative evaluation: moderating role of self-esteem. Health Psychol Open. 2018;5:2055102918774251. doi: 10.1177/2055102918774251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Costa Cabanillas M, López Méndez E.. Educación Para la Salud: Guía Práctica Para Promover Estilos de Vida Saludables. Spain: Pirámide; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kobel S, Wirt T, Schreiber A, et al. Intervention effects of a school-based health promotion programme on obesity related behavioural outcomes. J Obes. 2014;2014:476230. doi: 10.1155/2014/476230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.