Abstract

Objectives To discover what dementia sufferers think is wrong with them, what they have been told and by whom, and what they wish to know about their illness. Background Ethical guidelines regarding telling truth appear to be equivocal. Declarations of cognitively intact subjects, attitudes of family members, and current psychiatric practice all vary, but no previous research has been published concerning what patients with dementia would like to know about their diagnosis and prognosis. Design Questionnaire study of patients' opinions. Setting Old Age Psychiatry Service in Worcester, United Kingdom. Participants Thirty consecutive patients with dementia. Results The quality of information received has been poor, and many patients have no opportunity to discuss their illness with anybody. Despite that, almost half of the participants in this study had adequate insight, and most declared that they would like to know more about their predicament. Conclusions Although many patients would like to know the truth, the rights of those who do not want to know should also be respected. Therefore, the diagnosis of dementia should not be routinely disclosed, but just as in other disorders, health care professionals should seek to understand their patients' preferences and act appropriately according to their choice.

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a syndrome, usually of a chronic and progressive nature, in which there is decline of cognitive functions, accompanied by deterioration in emotional control, language skills, and social behavior. It occurs in Alzheimer disease, cerebrovascular disorders, and other conditions primarily or secondarily affecting the brain. Although dementia may begin at any age, most frequently it affects elderly persons, particularly after age 75 years. In most cases, its course is irreversible; despite significant progress, no effective treatment is currently available. Trying to help people with dementia is not only a challenge to physicians' professional skills but also confronts us with difficult questions about the limits of individual autonomy and medical paternalism, the dignity of persons, and their best interests.

In this article, I address an apparently simple problem concerning the giving of diagnostic information to people with dementia. A recent survey of old age psychiatry consultants showed that most of them “rarely” or only “sometimes” informed their patients about the diagnosis and almost never about the prognosis. Providing information seemed to depend on the level of impairment. In all, 38% of consultants “nearly always” informed patients with mild dementia, but in those with moderate and severe dementia, only 13% and 6%, respectively, discussed the diagnosis with their patients. However, 98% of the respondents “nearly always” informed patients' families and carers about the diagnosis and prognosis.1 Similar practice has been observed among geriatricians, although they tend to tell their patients with mild dementia more and their carers less than psychiatrists do.2

Table 1.

| Patients' expressions of their condition* |

|---|

|

Numbers in parentheses indicate the score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Most (57%-83%) relatives of dementia sufferers do not want the patient to be told the diagnosis, but more than 70% of the relatives would want to be told the truth if they had the disorder themselves.3,4 However, in cases where the diagnosis had been given, most of the carers found it helpful both for themselves (98%) and for the patients (84%).5 Only 1 study attempted to elicit patients' preferences. When attendees at 2 primary care practices were presented with a vignette of a patient with Alzheimer disease, most (92%) declared they would like to know the truth. Almost the same proportion (87%) stated that members of their families or friends should have been fully informed. However, the participants in this study were cognitively intact, and almost half of them were younger than 50 years.6 I am not aware of any published study exploring the wishes and preferences of patients with dementia, and therefore, I undertook this inquiry.

WHAT DO PATIENTS WITH DEMENTIA WANT TO KNOW?

My aim was to explore what the patients think is wrong with them, whether and what they have been told by their physicians about their condition, and what they would like to know about their illness. Thirty consecutive patients seen by me between October and December 1997 in the Old Age Psychiatry Service in Worcester participated in the study. Twenty were women. The patients ranged in age from 63 to 92 years (mean, 81 years). At the time of examination, 11 participants were inpatients, and 19 were outpatients. They had been in contact with the psychiatric service from 1 day to 17 years (mean, 1 year 10 months). All had a clinical diagnosis of dementia based on International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) criteria,7 including Alzheimer disease (n=11), vascular dementia (n=9), and other or unspecified dementias (n=10). In addition, consensus guidelines were used to make a diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies in 1 of the otherwise unspecified dementias.8 Participants' cognitive states were assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination9; scores ranged from 7 to 29 (median = 18, and mean = 18). All participants gave verbal consent and answered a set of standard questions regarding the information they had received about their illness (the questionnaire is available from the author on request). The answers were recorded verbatim and will be the subject of further analysis.

INSIGHT:

“What do you think is wrong with you?”

I assumed that the participants had adequate insight if they were able to give the correct diagnosis or, at least, to describe adequately their main symptoms. Of the 30 participants, 14 (47%) fulfilled these criteria. Most complained of problems with memory. No participant used the word “dementia,” but a few were able to accurately describe their conditions. Examples are shown in the first box.

The rest of the participants (16/30) either denied any problems or gave implausible explanations for their predicaments, such as: “loneliness,” “old age,” “stomach upset,” and the like. Four patients simply said “don't know” without further elaboration.

“What have you been told about your illness?”

Of the 30 participants, 20 reported that nobody had ever talked with them about their illness. Only 5 had had an opportunity to discuss it with their physicians. Sometimes the information was provided by nurses (3 participants) and friends (2 participants) but never by the family members. Only 1 participant said that she had been told her diagnosis. In 2 cases, the professionals attempted to reassure the patients (“There is not much wrong with you”) and advised them to take prescribed medication. Three participants reported clearly untrue explanations allegedly given by their physicians: hearing impairment, angina pectoris, and bereavement had been suggested as responsible for their present conditions. Two participants declared that the content of the information they were given was insulting (“She told me I was mad,” and “She said I was completely out of my balls and very needful”). Two participants either did not remember or could not understand what the informers had been trying to tell them.

“What would you like to know?”

Most of the participants with dementia (21/30) declared they would like to know what was wrong with them or wished to get more information if they already knew. Ten wanted to know their diagnoses, 5 were interested in the possibility of improvement, and 1 wished to know more about the causes of the disorder. Sometimes they could not specify what exactly they would like to know (4 participants), but some of their questions might have been difficult to answer, for example: “Why me?” or “How long will I suffer?”

Table 2.

| Patients' denial of dementia* |

|---|

|

Numbers in parentheses indicate the score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Where the participants specified whom they would wish to give them information about their illnesses, most (8/12) preferred that it should be their physician. Only rarely did patients feel that they should receive the information from other persons such as family members (2 participants) or anybody with adequate knowledge (2 participants).

Patient who does not want to know

Nine participants (30%) did not want to know what was wrong with them or to receive any information about their illness. Although we did not asked them why, some of them spontaneously tried to explain their choice. Their motives seem to display a wide spectrum from probably full insight through more or less conscious decisions not to know the truth to complete denial of their illness (see second box).

I could not find any clinical or demographic characteristics indicating those who would prefer to be told from those who would not.

DISCUSSION

Dementia and the problem of truth-telling

Methodologic limitations of the study may reduce the credibility of its results. The study has been based only on the declarations of patients, without attempting to verify them by their therapists or to compare them with the information given to carers. The subjects were cognitively impaired and because of the memory deficits, might not have been able to recall what they had been told. In the milder cases, the cognitive decline may be seriously threatening for many patients. To cope with the anxiety and to maintain their self-esteem, they might use various psychological defense mechanisms, such as denial and minimalization of the impairments, avoidance in discussing the problem, or vagueness and circumstantiality when forced to do so.10 Such defense mechanisms may render their statements less accurate, as has frequently been observed in other disorders—even in many terminally ill patients who have been told their diagnosis but simply deny they have been told.11 However, almost half of the participants with dementia had satisfactory insight, and 21 (70%) clearly declared they would like to know more about their illness. When in a parallel inquiry their statements were compared with those of cognitively intact peers with functional (predominantly depressive) disorders, no significant differences were found in the quality of received information, level of insight or the proportion of those willing to know about the illness (D Battin and M Marzanski, unpublished data). Of course, this is a small study from only 1 old age psychiatry service, so results of similar studies else-where might differ. However, the self-reported reluctance of physicians from other centers to disclose information about diagnosis to dementia sufferers strongly suggests that the pattern in Worcester is not unique.

Ethical codes and telling the diagnosis

Moreover, in the codes of medical ethics, the guidelines regarding disclosure of diagnosis are equivocal and may be interpreted in various ways. In the Hippocratic Oath, nothing about telling truth is explicitly stated. Nevertheless, even here a conflict exists between difficult-to-reconcile demands. Physicians should practice their art with purity and holiness, which may imply veracity; on the other hand, they should follow only that system or regimen that they consider beneficial to their patients, and they should abstain from anything that is deleterious and mischievous. Of course, the truth about dementia may be deleterious, mischievous, and devastating. A modern restatement of the Hippocratic Oath, known as the Declaration of Geneva (1947), seems to ignore the problem of veracity, stating simply that the health of the patient should be the physician's first consideration. The International Code of Medical Ethics (1968 and 1983) demands that a physician deal honestly with patients and colleagues, but this concerns competence and professional misconduct, rather than telling patients what is wrong with them. In the Declaration of Lisbon (1981), the World Medical Association stated: “The patient has the right to accept or refuse treatment after receiving adequate information.”12 This may suggest that telling the truth about diagnoses is a mere prerequisite to the choice of treatment. This impression seems to be reinforced in the ethical guidelines for the psychiatric profession. The World Psychiatric Association's Declaration of Hawaii (1977 and 1983) says13:

The psychiatrist should inform the patient of the nature of the condition, therapeutic procedures, including possible alternatives, and of the possible outcome. This information must be offered in a considerate way, and the patient must be given the opportunity to choose between appropriate and available methods.

But does this mean that psychiatrists have the duty to provide the information when there is no treatment? And how truthful should be the “considerate way”? Does it imply the whole truth? As much as the patient wants? As much as the patient's physician believes is sufficient? The General Medical Council (1995) recommends that physicians, to establish and maintain trust in their relationships with patients, must give them “the information they ask for or need about their condition, its treatment and prognosis... in a way they can understand.”14(p4) In practice, patients with dementia rarely ask for the information, and many physicians seem to think that because there is no cure to offer, such knowledge may be only detrimental and, therefore, not needed in therapeutic relationships. But can the relationships be successful without telling the truth?

Ethical theories and telling the diagnosis

Two schools of ethical thought address these dilemmas. Deontology (study of the field of professional ethics and duties) assumes that lying and deception are wrong in themselves and that clinicians, like everyone else, have a moral duty to tell the truth. Competent patients have a right to know their diagnosis; this information belongs to them, and they should be told the truth regardless of the consequences. Consequentialism insists that the decision to tell or not to tell depends on the details of the clinical situation, and the physician should decide which course of action might be least harmful and produce the best results for the patient.

In the deontologic approach, the word “competent” may cause reservations—it is difficult to understand why any illness might deprive the sufferer of the right to know about it. Competence is usually defined with respect to a particular task or performance, and the only relevant skill here is that of being able to “take in” diagnostic information. At the moment, the most prominent advocates of truth-telling seem to think that the nature and degree of the disease may limit the right to information. Pitt claims that “although there is probably no point in telling those whose Alzheimer's disease is so advanced that they cannot understand their diagnosis, in all other cases the right of those who have presented as patients, to know what is thought to be wrong with them should be respected.”15 But it remains controversial when, if ever, a person loses that right and whether incompetence (defined by others as inability to understand diagnostic information) is enough.

Regarding the consequentialist view, it might be argued that in doctor-patient relationships, nothing is more difficult to predict than the outcome of our own predictions. Physicians commonly tend to attribute their own fears and hopes to the patients—surprisingly often, the patients do not meet those expectations. In the 1950s, 90% of physicians did not inform their patients about the diagnosis of cancer.16 One of the early arguments for disclosure was the availability of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, which could alter the course of the disease. The need for a patient's consent to initiate such treatment outweighed previous concerns about possible harm associated with breaking the bad news. Only subsequently has it been proved that most patients want to know their diagnosis and its consequences, and now 97% of physicians tell their patients about the nature of the disease.17 Perhaps a similar change of attitudes will occur in old age psychiatry after the introduction of the new “antidementia” drugs, and appeals in this direction have already been launched.18,19 Today, the attitudes and practice of old age psychiatrists remain different from those of their colleagues from other specialties. Even in patients with schizophrenia and those with affective disorders, psychiatrists tend to inform their patients much more frequently—58% and 90%, respectively.20

Arguments in favor of truth-telling

According to Beauchamp and Childress,21 the main arguments obligating veracity are the following.

Respect for autonomy

Lies and deceit breach the autonomy of a person.22 Patients cannot make valid decisions unless they are fully informed. That usually involves informed consent to treatment, but of course, other decisions need to be made regarding legal aid, driving, finances, and planning for the future. The argument is not as obvious in patients with profound dementia who are no longer competent free agents and whose self-governance may be seriously limited. Agich has argued that the liberal concept of autonomy, which stresses independence and freedom from interference from others, is neither appropriate nor suitable here.23 Respect for the autonomy of dementia sufferers entails a commitment to identify and establish the conditions necessary to continue their lives in the way they are still able to and as closely as possible to the way they have normally lived. Such a commitment should involve hope resulting, in Agich's view, from meaningful relations with others. Could delivery of the devastating truth serve them better than not telling the truth?

Need for trust in doctor-patient relationship

Mutual trust cannot be built on deception and lies. In addition, concealment, even with good intentions, once started, probably would have to be continued. Its escalation might easily lead to abuse and harm of those not fit enough to be informed by those who can manipulate them according to their own needs and beliefs. On the other hand, therapeutic relationships in severe dementia may be difficult or impossible to establish, and the professionals often seem to work rather for the carers than directly for the patients. It seems also to be true that many close relations have been threatened or destroyed by too much candor.

Acknowledgment of reciprocal obligations, fidelity, and promise keeping

Any social contract involves mutual rights and obligations. In therapy, the contract concerns specifically the patient's health and should include the right to honest information about diagnosis and prognosis. However, many patients with dementia arguably are not able to enter any social contract simply as a direct result of their cognitive impairment, and the primary obligation of their physicians remains the principle “not to harm.” It has also been claimed that physicians, like everyone else, have a duty not to lie but are not duty-bound to avoid deception.24

Arguments for limited truth-telling or lying

Arguments for limited disclosure and deception quoted by Beauchamp and Childress21 include the following.

Therapeutic privilege

Honesty should not be confused with cruel openness,25 and if disclosure of the information seems to be harmful to the patient, the physician may be justified in withholding the information or even in using benevolent deception. The therapeutic privilege has a long tradition in medical practice, although more recently it has been criticized as an example of unacceptable paternalism. Misleading the patient contributes to the cult of expertise surrounding the medical profession and to a view of physicians not as providing a service, but as guardians of a special wisdom that they may determine when, and to whom, to divulge.26 However, paternalism frequently appears to be unavoidable in dementia care, and some professionals still defend telling lies to cognitively impaired patients.27 After all, anxiety, depression, and catastrophic and psychotic reactions do occur as the result of disclosure,28 and even suicides committed by patients unable to live with the burden have been reported.29

Patients are not able to understand the information

A convincing excuse for not disclosing the diagnosis is when patients have difficulties in acquiring new information complicated by memory deficits, impaired use of language, and inability to understand abstract concepts. But it may be argued that just because of the nature of dementia, patients should know well in advance about the threats to their intellectual functioning. They experience their illness and deserve an explanation of what is happening to them. Moreover, cognitive deficits do not remove their right to know the truth—they only make it more difficult for the physician to provide understandable information to the patient. Lying and deceiving seem to deny them due respect and degrade their dignity. As in any other group of disorders, patients with dementia require affirmation because they are persons, not just because they have been examined and found rational and competent. The truth may be neither fully understood nor remembered by the patient and difficult for the physician, but neither of these problems should remove the obligation to be honest and truthful.

Some patients do not want to know the truth about their condition

Besides the right to know, there is also the right not to know. Patients may prefer to ignore the truth completely or to select only those parts of it that they want to know. If we accept that physicians ought to respect their patients' wishes, then the important issue is not what family members, other patients, or professionals think, but what the patient in the particular circumstances wants.30 In my study, a substantial proportion of the participants (30%) preferred not to be informed about their illness, and their motives seemed to be diverse. This requires careful attention from health care professionals, who should not force unwanted information on patients but should seek to understand their patients' preferences and act according to their choices.

CONCLUSIONS

Veracity appears to be a difficult virtue and a difficult-to-fulfill obligation. Reconciling conflicting principles and judging how much information a patient should be given are not easy. Additional ambiguities may arise because of the difficult, sometimes impossible, task of balancing autonomy and paternalism. A review of the literature shows that in dementia, it is also unclear whether knowing the truth about one's health is the right of the person or a privilege available to those who are sufficiently bright to understand the information, brave enough to request it explicitly, and strong enough to cope with its burden. My study suggests that we ought to ask patients with dementia whether they wish to know more about their diagnosis. Each patient must be approached individually and his or her choices respected, whatever the level of impairment. Furthermore, having discussed the diagnosis once, the physician may need to go over it again, which implies that physicians must have the requisite communication skills to provide information in various ways. However, the effect of telling or not telling patients with dementia their diagnosis remains unknown and requires a further prospective study.

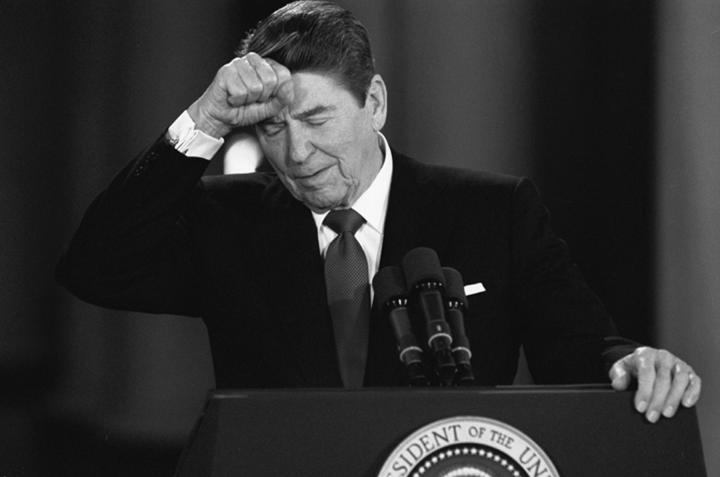

Figure 1.

Ronald Reagan in 1987, 7 years before the public announcement that he had Alzheimer disease. Did his physicians discuss the diagnosis with him?

© Dennis Cook/AP

Acknowledgments

I thank Professor K W M Fulford for his valuable comments and encouragement during the preparation of this article and Dr D Battin for his inspiration and support for the study.

Competing interests: None declared

This article was published in J Med Ethics 2000;26:108-113

Marek Marzanski is a Consultant Psychiatrist at the Coventry Healthcare National Health Service Trust, UK.

References

- 1.Rice K, Wagner N. Breaking the bad news: what do psychiatrists tell patients with dementia about their illness. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994;9: 467-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice K, Warner N, Tye T, Bayer A. Telling the diagnosis to patients with Alzheimer's disease: geriatricians' and psychiatrists' practice differs. BMJ 1997;314: 376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maguire CP, Kirby M, Coen R, Coakley D, Lawlor BA, O'Neill D. Family members' attitudes toward telling the patient with Alzheimer's disease their diagnosis. BMJ 1996;313: 529-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes RC. Telling the diagnosis to patients with Alzheimer's disease: relatives should act as proxy for patient [letter]. BMJ 1997;314: 375-376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AD, King EM, Hindley NJ, Barnetson L, Barton J, Jobst KA. The experience of research participation and the value of diagnosis in dementia: implications for practice. J Ment Health 1998;7: 309-321. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erde EL, Nadal EC, Scholl TO. On truth telling and the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. J Fam Pract 1988;26: 401-406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992: 45-56.

- 8.McKeith I, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. Neurology 1996;47: 1113-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein M, Folstein SE, McHugh PB. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12: 189-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahro M, Silber E, Sunderland T. How do patients with Alzheimer's disease cope with their illness? a clinical experience report. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;93: 291-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. London: Tavistock; 1970.

- 12.British Medical Association. Medical Ethics Today: Its Practice and Philosophy. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 1993.

- 13.Bloch S, Chodoff P, eds. Psychiatric Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- 14.The Duties of a Doctor: Good Medical Practice: Guidelines to Doctors. London: General Medical Council; 1995.

- 15.Pitt B. You've got Alzheimer's disease: telling the patient. Curr Opin Psychiatry 1997;10: 307-308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitts WT, Ravelin IS. What Philadelphia physicians tell patients with cancer. JAMA 1953;153: 901-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novack DM, Plumer R, Smith RL, Ochitill H, Morrow GR, Bennet JM. Changes in physicians' attitudes toward telling the cancer patient. JAMA 1979;241: 897-900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyers S. Telling patients they have Alzheimer's disease. BMJ 1997;314: 321-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alzheimer Scotland. The Right to Know? Edinburgh: Action on Dementia; 1997.

- 20.Green RS, Gantt AB. Telling patients and families the psychiatric diagnosis: a survey of psychiatrists. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1987;38: 666-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beauchamp TC, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994; 395-461.

- 22.Hope T. Deception and lying [editorial]. J Med Ethics 1995;21: 67-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agich SJ. Autonomy and Long Term Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993.

- 24.Jackson J. Telling the truth. J Med Ethics 1991;17: 5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson J. On the morality of deception: does method matter? a reply to David Bakhurst. J Med Ethics 1993;19: 183-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bakhurst D. On lying and deceiving. J Med Ethics 1992;18: 63-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cutcliffe J, Milton J. In defence of telling lies to cognitively impaired elderly patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1996;11: 1117-1118. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drickamer M, Lachs MS. Should patients with Alzheimer's disease be told their diagnosis? N Engl J Med 1992;326: 947-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rohde K, Peskind ER, Raskind MA. Suicide in two patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43: 187-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillon R. Telling the truth and medical ethics. In: Philosophical Medical Ethics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 1986: 100-105.