Abstract

Background

Definitions are essential for effective communication and discourse, particularly in science. They allow the shared understanding of a thought or idea, generalization of knowledge, and comparison across scientific investigation. The current terms describing olfactory dysfunction are vague and overlapping.

Summary

As a group of clinical olfactory researchers, we propose the standardization of the terms “dysosmia,” “anosmia,” “hyposmia,” “normosmia,” “hyperosmia,” “olfactory intolerance,” “parosmia,” and “phantosmia” (or “olfactory hallucination”) in olfaction-related communication, with specific definitions in this text.

Key Messages

The words included in this paper were determined as those which are most frequently used in the context of olfactory function and dysfunction, in both clinical and research settings. Despite widespread use in publications, however, there still exists some disagreement in the literature regarding the definitions of terms related to olfaction. Multiple overlapping and imprecise terms that are currently in use are confusing and hinder clarity and universal understanding of these concepts. There is a pressing need to have a unified agreement on the definitions of these olfactory terms by researchers working in the field of chemosensory sciences. With the increased interest in olfaction, precise use of these terms will improve the ability to integrate and advance knowledge in this field.

Keywords: Olfaction, Definition, Anosmia, Hyposmia, Parosmia, Dysosmia, Normosmia, Hyperosmia, Olfactory intolerance, Phantosmia, Olfactory hallucination

Introduction

Definitions provide a foundation for understanding concepts. They allow for the shared understanding of a thought or idea and serve as a means to generalize knowledge. Definitions, especially in science, are essential for effective communication and discourse and are crucial to the scientific endeavor. Without a clear understanding of what an examined phenomenon is, or is not, scientific investigation grasps at clouds.

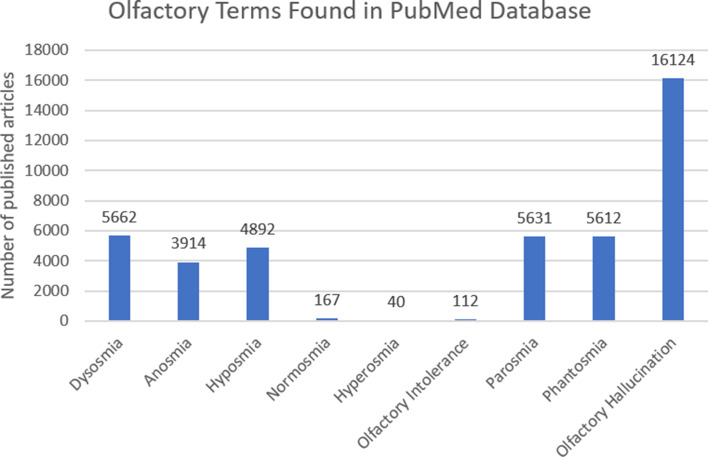

In the words of Cubelli and Salla (2017), “the meaning of a noun should allow all speakers of the same language to think and represent the same object in the same way” [1]. A literature search on PubMed showed that thousands of publications mentioned terms related to olfaction that are included in this paper (Fig. 1). However, despite widespread use of these terms in publications, there still exists some disagreement regarding the definitions of these terms [2, 3], where, for example, “dysosmia” can mean quantitative and qualitative olfactory dysfunction [2, 4] but was also previously synonymous with “parosmia” [5]. In the same way, “cacosmia” has been used to mean both what we now term “parosmia” and “phantosmia” [2, 4]. Some authors have used “troposmia” for the symptom now defined as “parosmia” [2] while “hyperosmia” refers to a quantitatively heightened olfactory function but is often only subjectively reported and not confirmed with olfactory testing [5, 6]. Similarly, “microsmia” has been used as a synonym for hyposmia [7]. These multiple overlapping and imprecise terms are confusing and hinder clarity and universal understanding of these concepts. An unambiguous universal description is beneficial for clear identification and classification of olfactory phenomena.

Fig. 1.

Olfactory terms in the PubMed database (as of January 2023).

A simple online search of seven terms included in this article revealed that several of them (usually hyposmia, normosmia, and phantosmia) were not included in standard dictionaries (e.g., Oxford [8], Merriam-Webster [9], Cambridge [10], Collins [11]) and some of the publicly available definitions were vague and imprecise. That is, anosmia and hyposmia were both defined as impairment of the sense of smell [12, 13]. Also, parosmia was defined as a “disorder of the sense of smell, especially as involving the perception of a non-existent odour” [14] – which may be confused with phantosmia or as “any disorder of the sense of smell” [15] – which may be confused to mean as either quantitative or qualitative olfactory dysfunction. In addition, hyperosmia was described as an “abnormally acute of the sense of smell” [16, 17] – where the use of the word “acute” refers to intensity and does not refer to its clinical meaning denoting temporality or time.

This article aimed to provide clear, unambiguous definitions to nine of the most commonly used olfaction-related terms, i.e., dysosmia, anosmia, hyposmia, normosmia, hyperosmia, olfactory intolerance, parosmia, and phantosmia (also termed olfactory hallucination). This is to allow writers and readers of olfaction-related literature to have a common understanding of what is meant when these words are used. To reduce miscommunication, we propose that these definitions be used in future scientific communication about olfaction.

Dysosmia

Dysosmia comes from Greek “dys-” meaning “bad,” “osme” which means “smell,” and “-ia” which is a usual termination for Greek terms of pathology [18]. It has previously been described to be related to qualitative olfactory dysfunction [6, 19, 20], and it has been used as a synonym to “parosmia” [5, 21, 22]. However, ”dysosmia” has also been used to describe only a quantitative olfactory loss [2, 23–25].

To avoid confusion, we propose that “dysosmia” be used as an umbrella term to describe the presence of quantitative and/or qualitative olfactory dysfunction [6, 26–31]. However, more specific terms listed below are recommended to better describe specific olfactory dysfunctions.

Anosmia

Anosmia is derived from the Greek “an-” meaning “without or not,” “osme” which means “smell,” and “-ia” which is a usual termination for Greek terms of pathology [32]. It has been in use since the early 19th century [33]. In the strictest meaning, it refers to the complete absence of the olfactory sense [34], but we extend it to a state where vague smell sensations may be present but are not enough to be useful in daily life, for tasks such as detecting dangers or appreciating foods or pleasant odors. Previously, some investigators, including some of the authors, have used the term “functional anosmia” for this present but unusable olfactory function. But because “functional” is often used in medicine to refer to physical symptoms in the absence of a known physical cause (often unexplained or psychosomatic) [35], we suggest the term “anosmia” as an umbrella term for cases where the assessment of the sense of smell shows no usable olfactory function. Olfactory tests show scores below the lower limit for hyposmia.

Assessment of olfaction using validated, standardized psychophysical olfactory tests, for example, “Sniffin’ Sticks” [36] or the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (SIT-40) [37] may demonstrate anosmia (although they cannot rule out the presence of vague olfactory sensations which are not usable in daily life). However, various tests may use different numerical cut-offs to define anosmia (see [31, 32]); hence, the diagnosis of “anosmia” depends to some degree on the test used [38]. In addition, psychophysical olfactory tests are typically based on multiple forced choice principles which means that even completely anosmic people obtain a score that overlaps with scores obtained by individuals with strongly decreased but not completely absent olfactory function [3]. In this sense, the term “anosmia” may be used to refer to both. More definitive support for the diagnosis of anosmia can be derived from test results based on reflective changes of breathing patterns when sensing an odor [39], electrophysiological, EEG-related tests [40–42], or structural brain imaging, for example, suggesting the absence of olfactory bulbs [43, 44].

The term “anosmia” has been related to various etiologies, including sinonasal, post-viral, post-traumatic, idiopathic, congenital, or neuropsychologic disorders [3]. It may be permanent or reversible depending on the cause [7]. When paired with particular adjectives, the term “anosmia” may take on different meanings. In particular, “specific anosmia” (sometimes “partial anosmia”) refers to the absence of smell perception for a particular odorous molecule or group of odorous molecules with an otherwise normal olfactory function and is thought to be a normal physiological trait [45].

Hyposmia

Hyposmia is derived from the Greek prefix “hypo-” meaning “under or beneath” [46]. It is used to describe olfactory dysfunction and refers to a quantitatively reduced ability to detect and identify the presence of certain odors. The word may be used to subjectively describe this reduction in olfactory function but is often used in the context of psychophysical testing (i.e., “Sniffin’ Sticks,” SIT-40, etc.). The distinction between “hyposmia” and “normosmia” is based on the performance of a sample of normal individuals from a particular age group in a particular olfactory test that has been generalized to a larger population. In the case of the “Sniffin’ Sticks” and the SIT-40, the 10th percentile of the distribution of the test scores of this group was chosen to define the border between hyposmia and normosmia. If this definition would be changed to 5%, then more individuals would reach the normosmic range when being tested. Hence, the definition of hyposmia is arbitrary to some degree.

To separate “hyposmia” and “anosmia,” the distribution of scores obtained in patients with anosmia is often used. In the case of the “Sniffin’ Sticks,” a composite score is used, consisting of the sum of scores for odor threshold (T), discrimination (D), and identification (I). The maximum TDI score possible for people with anosmia is 16 [47] and this is, therefore, the lower limit for “hyposmia” [48]. In SIT-40 [49], however, the term “microsmia” was described as a “condition of lessened smell function” that specifically relates to scores on this test only. “Microsmia” is further subdivided into “severe,” “moderate,” and “mild.” However, this subdivision is heuristic, and the word “microsmia” does not distinguish from “partial anosmia” and “hyposmia” as “…individuals on the borderlines may change boundaries, reflecting test-retest variation” [49]. Despite the slightly arbitrary boundary, the distinction between decreased and extremely little or no olfactory function is useful in clinical and research applications.

The current quantitative assessment of hyposmia is based on comparison with a group of young (21–30 years), healthy individuals who typically have the best olfactory function measurements of any age group. If the test scores were compared to those from the 71–80 year age group, the scores for the hyposmic category would be different because, in general, older people score lower on smell tests. The question arises whether, in individual testing, would an age-related categorization be more appropriate? The answer to that is not straightforward. On one hand, age-related categories can be helpful in counseling patients that their scores are normal for their age range, and as such, they can avoid the need to have unnecessary medical workup done based only on a test score. On the other hand, it is not helpful when people are labeled as having age-related normosmia when their relatively low function does not allow them, for example, to identify and subsequently avoid rotten milk. Much of how an age-related olfactory test result is handled depends on (1) the subjective complaint of the individual and (2) the clinical context in which the test results are interpreted.

Like anosmia, the term “hyposmia” has been related to various etiologies [3] and may be a sign of altered olfactory processing, although not to a degree of severity that is observed in anosmia. It may also be reversible or permanent depending on the cause [7] but has been attributed to similar causes identified for “anosmia.” However, it is worth noting that transient hyposmia may occur due to accelerated or prolonged olfactory adaptation and may be observed in chronic exposure to certain workplace chemicals [50]. In addition, hyposmia has been regarded as a frequent non-motor symptom related to Parkinson’s disease and may even predate motor symptoms by years [51, 52].

Normosmia

Normosmia comes from the Latin word “norma” meaning “standard or pattern of practice or behavior” [53]. It is used to describe normal olfactory function and refers to the absence of any olfactory-related complaints in terms of quantitative olfactory function. Accordingly, it may be that patients with olfactory dysfunction in the form of parosmia (see below) score in the normosmic range.

In terms of psychophysical testing, values of ≥30 in SIT-40 and ≥30.75 in the composite TDI score for “Sniffin’ Sticks” correspond to normal smell function. Similar to how the cut-offs for “hyposmia” were determined in the “Sniffin’ Sticks,” “normosmia” also relied on the scores of a particular group of young and healthy individuals (21–30 years) to determine what is normal (composite TDI score: 10th percentile = 30.75).

Hyperosmia

Hyperosmia comes from the Greek prefix “hyper-” meaning “over or beyond” [54]. It describes a quantitative increase in olfactory function, corresponding to an exceptionally high score in a psychophysical olfactory test (e.g., above the 90th percentile). Hyperosmia is not considered to be a type of olfactory dysfunction, and we propose that this term be used only in relation to results of psychophysical olfactory tests.

In contrast, the term “olfactory intolerance” is proposed to describe a qualitative olfactory dysfunction where individuals who do not experience odor distortions complain of a subjectively enhanced sense of smell and are intolerant to everyday odors. This condition is rare [5, 45], but it has been reported in certain conditions such as migraines, pregnancy, epilepsy, and Addison’s disease [6]. The term “hyperosmia” was previously used to describe this phenomenon. However, since the subjectively enhanced sense of smell is not consistently confirmed by psychophysical olfactory measures [6, 55] and does not equate to increased olfactory performance, we propose that the term “olfactory intolerance” be used for this particular phenomenon instead of “hyperosmia” for clarity.

Parosmia

Parosmia comes from the Greek prefix “para-” meaning “beside.” The word has been in use as early as the 19th century [14, 56] but has gained popularity with the increased frequency of this phenomenon due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been used as a synonym for “dysosmia” [5, 22] (see also above), while historically “parosmia” was used to mean “any disorder of the sense of smell” [15]. Its present use refers to a symptom of qualitative olfactory dysfunction where distorted odor perception occurs in the presence of an odor. Odors are often perceived as unpleasant [57] (described as, e.g., “smoke,” “feces,” “chemical,” “vomit”). Some molecules are more likely than others to produce parosmic sensations [58].

Parosmia is determined based on an individual’s self-report and may be challenging to assess. A grading system that includes frequency of occurrence, intensity, and social effects has been used to quantify the severity of parosmia [59]. In addition, a 4-item questionnaire [60] and a test based on the ratings of odors ([44], but also see [45]) have been proposed. Currently, there is no validated test or psychophysical measure that is widely recognized and utilized to test for parosmia. In certain cases, parosmia may improve with obstruction of airflow through the nasal cavity. The distorted odor perception is usually unpleasant but may occasionally be pleasant (also “euosmia”) [61].

Parosmia is often associated with post-infectious olfactory dysfunction but may also be observed in sinonasal, post-traumatic, or idiopathic olfactory dysfunction [3] and has been reported in the literature as an isolated phenomenon after general anesthesia [62]. It often coincides with either a quantitative olfactory dysfunction (typically hyposmia) [63] or with phantosmia, but it may also occur independently. The exact mechanism of parosmia remains unclear, but it has been proposed to involve problems with odor coding affecting both the peripheral and central olfactory systems [64].

Parosmia is also believed to be associated with olfactory system repair and may be seen as a sign of recovery in some cases [64]. There is still some debate in the clinical olfaction community as to whether parosmia is a positive prognostic sign.

Phantosmia (Also Termed Olfactory Hallucination)

Phantosmia comes from the Latin word “phantasma” meaning “hallucination or illusion” [65]. It refers to the perception of an odor, often unpleasant (i.e., burned, rotten, fecal, or chemical [2, 25]) in the absence of an odor stimulus [2, 3]. Distinguishing the presence or absence of an odor stimulus may depend on the perception of other individuals in the same environment (i.e., whether they perceive the same odor the patient does or otherwise).

However, to describe a symptom as “phantosmia,” it is necessary to exclude an endogenous odor source from the nose or sinuses (e.g., mucopurulent discharge from sinuses, fungal ball, foreign bodies, tumor, etc.). There is no consensus whether there is need for a term that describes individuals who complain about an unpleasant odor in the nose with the eventual discovery of an endogenous odor source in the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, or oral cavity. Nevertheless, it is important to do a complete and thorough ear, nose, and throat physical examination (including nasal endoscopy, also computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging in selected cases) to help rule out endogenous odor sources and better understand olfactory complaints.

Cacosmia is a general term previously used to mean a “negatively perceived olfactory distortion” but was also used as a term for either parosmia, phantosmia, or both [2, 4]. Due to the confusion potentially brought about by these different meanings, we propose that the terms “phantosmia” and/or “parosmia” be used instead of “cacosmia.” However, should one decide to use the word “cacosmia,” it is important to clearly describe what meaning the word holds for its use.

Leopold (2002) also made a distinction that sensations in patients with “phantosmia” last longer than a few seconds, while those in “olfactory hallucination” last only a few seconds [2]. Given that this phenomenon is difficult to measure, temporality may not be a relevant distinction that is required for this term. Therefore, we propose that the terms “phantosmia” and “olfactory hallucination” be regarded as synonymous. Phantosmia is a term that is generally familiar to otorhinolaryngologists; however, the term “olfactory hallucination” has been noted to appear more frequently in the neurologic literature and might have been associated with psychiatric disorders. Since the exact pathophysiology is unclear, we deliberately propose to make the parallelism between phantosmia and olfactory hallucination to improve communication further and increase the awareness of progress in the various fields related to olfaction.

Henkin (1971) also previously used phantosmia as “a term describing the intermittent or persistent odor… perceived when no apparent odor is inhaled.” However, there exists a phenomenon regarded as “odor-induced phantosmia” or “smell lock” where one starts with the perception of odor from an apparent odor source, but the odor lingers and continues even when the odor source is no longer present. Hence, this circumstance still fits the criteria of phantosmia but may have initially started out from the perception of an odor. Along the same avenue of phenomena, some patients report “nasal breathing-related phantosmia” where odor perception occurs in the absence of an apparent odor source only when breathing through the nose but is eliminated once airflow through the nose is restricted (i.e., by pinching or occluding the nostrils).

Phantosmia is often associated with post-infectious and post-traumatic olfactory dysfunction but may also be observed in neuropsychiatric, sinonasal, and idiopathic olfactory dysfunction [3]. Like parosmia, it often coincides with either a quantitative olfactory dysfunction (often anosmia) [63] or with parosmia, but it may also occur independently in individuals with normosmia. Similar to parosmia, determination of the presence of phantosmia is dependent on self-report as there is currently no validated test or psychophysical measure available to test for phantosmia. Still, specific questions have been proposed to identify the presence of phantosmia [60]. The exact mechanism of phantosmia remains unknown but is believed to involve an abnormality anywhere along the olfactory pathway. However, phantosmia may be a symptom of a deafferentiation syndrome and, therefore, indicates poor prognosis in some cases [25, 64, 66].

Measured versus Subjective

In the literature, the determination of olfactory function can be “measured” or “subjective.” “Measured” usually denotes a numerical value from a validated, often psychophysical, olfactory test that quantifies olfactory function. It is often associated with terms related to quantitative olfactory dysfunction (i.e., “anosmia,” “hyposmia,” and “normosmia”). The word “subjective” refers to an individual’s self-reported olfactory function (i.e., poor-same-better or bad-equivocal-good). Qualitative olfactory dysfunction (i.e., parosmia, phantosmia) is often regarded as “subjective,” given that validated psychophysical tests are currently not available to evaluate these conditions. However, the word “subjective” may also be added to quantitative terms (i.e., anosmia, hyposmia, or normosmia) to mean self-reported olfactory function or dysfunction that is not confirmed by psychophysical olfactory testing. An exception to this is the term “olfactory intolerance” which we propose instead of “subjective hyperosmia.” This is to avoid confusion, given that “hyperosmia” is not considered as a pathologic state, while “olfactory intolerance” is. Although some patients may show congruence of measured and subjective olfactory function, some continue having subjective complaints in the setting of normal olfactory test scores and vice versa. Despite measured olfactory function often being the basis for management of patients with olfactory complaints, subjective olfactory function may sometimes better reflect quality of life. A clear distinction between “measured” and “subjective” olfactory function is important to consider, especially when they are not congruent, to enable clinicians to provide more holistic counseling and patient care.

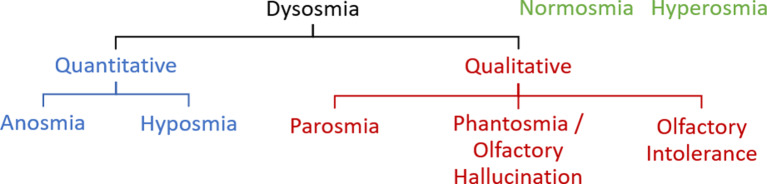

A summary of the definitions of the abovementioned olfactory terms can be found in Table 1, and a concept diagram of these terms can be found in Figure 2. This paper serves as a starting point in the efforts toward common understanding and use of the aforementioned olfactory terms. Future studies may re-evaluate for possible changes in the way these words are used in scientific publications years from now.

Table 1.

Summary of common olfactory term definitions

| Olfactory term | Definition | Related terms |

|---|---|---|

| Dysosmia1 | Olfactory dysfunction, in general (quantitative or qualitative) | Quantitative olfactory dysfunction Qualitative olfactory dysfunction |

| Anosmia | Quantitatively reduced olfactory function to the extent that the sense of smell is not useful in daily life | Functional anosmia |

| Hyposmia | Quantitatively reduced olfactory function | Microsmia |

| Normosmia | Quantitatively normal olfactory function | |

| Hyperosmia | Quantitative increase in olfactory function, corresponding to an exceptionally high score in a psychophysical olfactory test (e.g., above the 90th percentile) | |

| Olfactory intolerance | Qualitative olfactory dysfunction where individuals, without odor distortions, complain of a subjectively enhanced perception of odors and are intolerant of everyday odors | |

| Parosmia1 | Distorted perception of an odor in the presence of an odor stimulus | Euosmia |

| Phantosmia or olfactory hallucination | Odor perception in the absence of an odor stimulus |

1For clarity, “parosmia” and “dysosmia” are not regarded as synonymous.

Fig. 2.

Concept diagram of olfactory terms.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we propose the standardization of the use of the terms “dysosmia,” “anosmia,” “hyposmia,” “normosmia,” “hyperosmia,” “olfactory intolerance,” “parosmia,” and “phantosmia” or “olfactory hallucination” in olfaction-related communication. Further specification as “measured” or “subjective,” when referring to olfactory function, is helpful in the clinical setting. Precise use of these terms will enhance scientific communication in a field that is set to grow further.

Acknowledgment

The idea for this manuscript was sparked by a discussion with Ilona Croy for which we are thankful.

Conflict of Interest Statement

A.K.H., B.N.L., A.A., A.W.F., S.G., E.H.H., C.H., I.K., M.L., A.M., P.P.M., T.M., J.M.P., S.C.P., J.V., A.W.L., and K.L.W. have no conflicts of interest to declare. C.P.: the author is a trustee of Fifth Sense and holds grants with the National Institute of Health Research, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Rosetrees Trust, ENT UK, and the Royal College of Surgeons. He has received personal fees from GSK, Sanofi, Stryker, and Olympus. T.H.: since 2019, T.H. did research together with and received funding from Sony, Stuttgart, Germany; Smell and Taste Lab, Geneva, Switzerland; Takasago, Paris, France; AspUraclip, Berlin, Germany; Baia Foods, Madrid, Spain; Burghart, Holms, Germany; and Primavera, Oy-Mittelberg, Germany.

Funding Sources

T.H. and A.K.H. are supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG HU 441/21-1; project number 468981129).

Author Contributions

A.K.H.: conceptualization, writing, review, and editing. B.N.L.: conceptualization, review, and editing. A.A., A.W.F., S.G., E.H.H., C.H., I.K., M.L., A.M., P.P.M., T.M., C.P., J.M.P., S.C.P., J.V., A.W.L., and K.L.W.: review and editing. T.H.: conceptualization, supervision, review, and editing.

Funding Statement

T.H. and A.K.H. are supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG HU 441/21-1; project number 468981129).

References

- 1. Cubelli R, Della Sala S. In search of a shared language in neuropsychology. Cortex. 2017;92:A1–2. 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leopold D. Distortion of olfactory perception: diagnosis and treatment. Chem Senses. 2002;27(7):611–5. 10.1093/chemse/27.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hummel T, Whitcroft KL, Andrews P, Altundag A, Cinghi C, Costanzo RM, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinol Suppl. 2017;54(26):1–30. 10.4193/Rhino16.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hong SC, Holbrook EH, Leopold DA, Hummel T. Distorted olfactory perception: a systematic review. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132(Suppl 1):S27–31. 10.3109/00016489.2012.659759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doty RL. Clinical disorders of olfaction. Handbook of olfaction and gustation. 3rd Ed;2015. p. 375–402. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doty RL, Bromley SM. Olfactory nerve (cranial nerve I). In: Goetz CG, editor. Textbook of clinical neurology. Third Edit. W.B. Saunders; 2007. p. 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel ZM, Holbrook EH, Turner JH, Adappa ND, Albers MW, Altundag A, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: olfaction. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2022;12(4):327–680. 10.1002/alr.22929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oxford English Dictionary [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.oed.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Merriam-Webster English Dictionary [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cambridge English Dictionary [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Collins English Dictionary [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anosmia [Internet]. Merriam-Webster English Dictionary. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/anosmia.

- 13.Hyposmia [Internet]. Merriam-Webster English Dictionary. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/hyposmia.

- 14.Parosmia, n. [Internet]. OED Online. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/138097.

- 15. Oxford University Press . Parosmia [Internet]. Oxford Concise Medical Dictionary. 2014. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199557141.001.0001/acref-9780199557141-e-7438?rskey=7392x4&result=8081. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dell B. Hyperosmia. The bantam medical dictionary. 6th ed.New York; 2009. p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyperosmia [Internet]. [cited 2022 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/hyperosmia.

- 18.dys- [Internet]. Oxford English Dictionary. 1989 [cited 2022 Oct 20]. Available from: https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/58862?redirectedFrom=dys-&#eid5880569.

- 19. Henkin RI, Schechter PJ, Hoye R, Mattern CFT. Idiopathic hypogeusia with dysgeusia, hyposmia, and dysosmia: a new syndrome. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc. 1971;217(4):434–40. 10.1001/jama.1971.03190040028006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frasnelli J, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction and daily life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262(3):231–5. 10.1007/s00405-004-0796-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hura N, Xie DX, Choby GW, Schlosser RJ, Orlov CP, Seal SM, et al. Treatment of post-viral olfactory dysfunction: an evidence-based review with recommendations. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10(9):1065–86. 10.1002/alr.22624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doty RL. Treatments for smell and taste disorders: a critical review. Handbook of clinical neurology. Netherlands; 2019. p. 455–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Petersen H, Götz P, Both M, Hey M, Ambrosch P, Bremer JP, et al. Manifestation of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis in head and neck. Rhinology. 2015;53(3):277–85. 10.4193/Rhino14.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ciurleo R, De Salvo S, Bonanno L, Marino S, Bramanti P, Caminiti F. Parosmia and neurological disorders: a neglected association. Front Neurol. 2020 Nov;11:543275. 10.3389/fneur.2020.543275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frasnelli J, Landis BN, Heilmann S, Hauswald B, Hüttenbrink KB, Lacroix JS, et al. Clinical presentation of qualitative olfactory dysfunction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;261(7):411–5. 10.1007/s00405-003-0703-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henkin RI. Disorders of taste and smell. JAMA. 1971;218(13):1946. 10.1001/jama.1971.03190260060028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saltagi MZ, Rabbani CC, Ting JY, Higgins TS. Management of long-lasting phantosmia: a systematic review. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(7):790–6. 10.1002/alr.22108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deeb W, Nozile-Firth K, Okun MS. Parkinson’s disease: diagnosis and appreciation of comorbidities. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;167:257–77. 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Manesse C, Ferdenzi C, Sabri M, Bessy M, Rouby C, Faure F, et al. Dysosmia-associated changes in eating behavior. Chemosens Percept. 2017;10(4):104–13. 10.1007/s12078-017-9237-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rea P. Olfactory nerve. Clinical anatomy of the cranial nerves. Academic Press; 2014. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vengalasetti YV, Chertow GM, Popat R. Dysgeusia and dysosmia in chronic kidney disease: NHANES 2011–2014. J Ren Nutr. 2022;32(5):537–41. 10.1053/j.jrn.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. iasuffix1 [Internet]. OED online. 2019. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/90676. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anosmia, n. [Internet]. OED online. 2010. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/8100. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Costanzo RM, DiNardo LJ, Reiter ER. Head injury and olfaction. In: Doty RL, editor. Handbook of olfaction and gustation. 2nd ed.New York: Marcel Dekker; 2003. p. 629–38. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ullas G, McClelland L, Jones NS. Medically unexplained symptoms and somatisation in ENT. J Laryngol Otol. 2013;127(5):452–7. 10.1017/S0022215113000339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR, Pauli E, Kobal G. Sniffin” sticks’. Olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses. 1997;22(1):39–52. 10.1093/chemse/22.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of the university of Pennsylvania smell identification test: a standardized microencapsulated test of olfactory function. Physiol Behav. 1984;32(3):489–502. 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90269-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doty RL. Psychophysical testing of smell and taste function. In: Doty RL, editor. Handbook of clinical neurology Elsevier; 2019. p. 229–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mainland J, Sobel N. The sniff is part of the olfactory percept. Chem Senses. 2006;31(2):181–96. 10.1093/chemse/bjj012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kobal G, Hummel T. Olfactory and intranasal trigeminal event-related potentials in anosmic patients. Laryngoscope. 1998;108(7):1033–5. 10.1097/00005537-199807000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schriever VA, Han P, Weise S, Hösel F, Pellegrino R, Hummel T. Time frequency analysis of olfactory induced EEG-power change. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185596–11. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hummel T, Kobal G. Olfactory event-related potentials. In: Simon SA, Nicolelis MAL, editors. Methods and frontiers in chemosensory research. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press; 2001. p. 429–64. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weiss T, Soroka T, Gorodisky L, Shushan S, Snitz K, Weissgross R, et al. Human olfaction without apparent olfactory bulbs. Neuron. 2020;105(1):35–45.e5. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duprez TP, Rombaux P. Imaging the olfactory tract (cranial nerve #1). Eur J Radiol. 2010;74(2):288–98. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Clinical diagnosis and current management strategies for olfactory dysfunction: a review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(9):846–53. 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.hypo-, prefix. [Internet]. OED Online. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/90443.

- 47. Kobal G, Klimek L, Wolfensberger M, Gudziol H, Temmel A, Owen CM, et al. Multicenter investigation of 1,036 subjects using a standardized method for the assessment of olfactory function combining tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257(4):205–11. 10.1007/s004050050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Oleszkiewicz A, Schriever VA, Croy I, Hähner A, Hummel T. Updated Sniffin’ Sticks normative data based on an extended sample of 9139 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(3):719–28. 10.1007/s00405-018-5248-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doty RL. The smell identification test administration manual. 3rd ed.Haddon Heights, New Jersey: Sensonics; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schwartz BS, Doty RL, Monroe C, Frye R, Barker S. Olfactory function in chemical workers exposed to acrylate and methacrylate vapors. Am J Public Health. 1989;79(5):613–8. 10.2105/ajph.79.5.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fjaeldstad A, Fernandes HM, Van Hartevelt TJ, Gleesborg C, Møller A, Ovesen T, et al. Brain fingerprints of olfaction: a novel structural method for assessing olfactory cortical networks in health and disease. Sci Rep. 2017 Jan;7:42534–13. 10.1038/srep42534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Haehner A, Hummel T, Hummel C, Sommer U, Junghanns S, Reichmann H. Olfactory loss may be a first sign of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2007 Apr;22(6):839–42. 10.1002/mds.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Norma n. [Internet]. OED Online. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/128268.

- 54.Hyper-, prefix [Internet]. OED online; 2022. [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/90273.

- 55. Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, Hellings PW, Kern R, Reitsma S, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020;58(Suppl S29):1–464. 10.4193/Rhin20.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nemnich PA. Lexicon Nosologicum Polygloton: omnium morborum symptomatum vitiorumque naturae et affectionum propria nomina decem linguis diversis explicata continens. Germany: Müller; 1801. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Parker JK, Methven L, Pellegrino R, Smith BC, Gane S, Kelly CE. Emerging pattern of post-COVID-19 parosmia and its effect on food perception. Foods. 2022;11(7):967. 10.3390/foods11070967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Parker JK, Kelly CE, Gane SB. Insights into the molecular triggers of parosmia based on gas chromatography olfactometry. Commun Med. 2022;2(1):58–9. 10.1038/s43856-022-00112-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hummel T, Hummel C, Welge-luessen A. Assessment of olfaction and gustation. In: Welge-Luessen A, Hummel T, editors. Management of smell and taste disorders. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 2014. p. 58–75. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Landis BN, Frasnelli J, Croy I, Hummel T. Evaluating the clinical usefulness of structured questions in parosmia assessment. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1707–13. 10.1002/lary.20955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Green TL, McGregor LD, King KM. Smell and taste dysfunction following minor stroke: a case report. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2008;30(2):10–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Iakovou I, Douvantzi A, Metaxas S. Anosmia after general anaesthesia: a case report. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(12):1367–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reden J, Maroldt H, Fritz A, Zahnert T, Hummel T. A study on the prognostic significance of qualitative olfactory dysfunction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007 Feb;264(2):139–44. 10.1007/s00405-006-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Whitcroft KL, Hummel T. Olfactory function and dysfunction. In: Flint P, Francis H, Haughey B, Lesperance M, Lund V, Robbins K, eds, et al. Cummings Otolaryngology. 7th ed.Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phantasma, n. [Internet]. OED Online. 2022 [cited 2022 Oct 6]. Available from: www.oed.com/view/Entry/142183.

- 66. Leung JS, Cordano VP, Fuentes-López E, Lagos AE, García-Huidobro FG, Aliaga R, et al. Phantosmia may predict long-term measurable olfactory dysfunction after COVID-19. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(12):2445–52. 10.1002/lary.30391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]