Abstract

Introduction

In the last decade, yoga has attracted much attention from researchers. Although there are many studies on yoga, research on the effect of prenatal yoga on pregnancy-related symptoms is limited. This study aimed to determine the effect of prenatal yoga on pregnancy-related symptoms.

Methods

The study was conducted at antenatal care services between June 2018 and October 2018 in Turkey. Simple random method was used to assign participants to the study arms. The yoga group attended a prenatal yoga program for 60 min once a week for 4 weeks. The control group received routine care. Data were collected before and after the intervention using the Descriptive Characteristics Form and Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory. Data analysis used descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation/standard error, and percentages), χ<sup>2</sup>, Mann-Whitney, and Wilcoxon tests. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The study was completed with 70 participants (the yoga group: 35; the control group: 35). The yoga group had a significantly lower posttest Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory Symptom Frequency Total Score than the pretest score (38.42 ± 18.76 vs. 32.77 ± 16.55, p < 0.05). The total score of the yoga group's gastrointestinal, respiratory, and mental health symptoms was reduced after the intervention (respectively, 6.74 ± 4.32 vs. 5.31 ± 3.38; 1.48 ± 1.26 vs. 1.05 ± 1.13; 7.08 ± 4.59 vs. 5.22 ± 3.48, p < 0.05). The yoga group had significantly lower mental health symptom scores than the control group (5.22 ± 3.48 vs. 7.34 ± 4.02, p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the control group's pretest and posttest Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory Symptom Frequency Scores.

Conclusion

Pregnancy-related symptoms were significantly reduced in the yoga group. It is thought that prenatal yoga may be effective on pregnancy-related symptoms. Yoga can be recommended to cope with pregnancy-related symptoms and support activities of daily living.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Complementary therapies, Yoga, Pregnancy-related symptoms

Introduction

Anatomical, physiological, and psychological changes during pregnancy lead to pregnancy symptoms [1]. The most common pregnancy-related symptoms are nausea, vomiting, urinary frequency, urinary system infections, fatigue, heartburn, sleep disturbance, backache, varicose veins, leg cramps, and constipation [1, 2]. Pregnant women (9.4–85.2%) turn to traditional and complementary medicine (TCM) and medical treatment to cope with pregnancy-related symptoms and stay healthy. Pregnant women see TCM as a holistic approach that responds to all their physical and psychological needs, so they often prefer TCM to improve pregnancy and childbirth outcomes [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. Yoga is a type of TCM that has been popular in recent years among pregnant women [4, 5, 7]. Yoga is a comprehensive approach that focuses on mental, physical, spiritual, emotional, and ethical teachings [8, 9]. Yoga affects the release of β-endorphins and neurotransmitters, resulting in physiological and neurophysiological changes. It provides relaxation by acting on the release of dopamine, serotonin, and cortisol, which are responsible for emotional changes [8, 9, 10]. It reduces the psychological symptoms common during pregnancy, such as stress, anxiety, depression, and state anger [11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. It helps pregnant women cope with physiological symptoms, such as problems in the circulatory system, urinary system, respiratory system, digestive system, and musculoskeletal system; overweight, fatigue, sleep problems, and high blood sugar [16, 17, 18]. Pregnant women who do yoga have stronger perineum muscles, and the spine, and shorter and less painful labour [8, 9, 11]. Research studies show that yoga in pregnancy helps reduce stress and depression and improves pregnancy outcomes [12, 13, 15, 19, 20]. Previous research can be considered the first step toward a deeper understanding of the impact of prenatal yoga on pregnancy; however, more research is needed [21, 22].

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the effect of prenatal yoga on pregnancy-related symptoms. This study is one of the limited numbers of studies investigating the effect of prenatal yoga on pregnancy-related symptoms in Turkey.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study conducted a pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design with a control group.

Hypothesis

H1: Posttest symptom frequency total score of PSI in the yoga group will be lower than the pretest.

H2: Posttest symptom frequency subscale scores of PSI in the yoga group will be lower than the pretest.

H3: Posttest symptom frequency total score of PSI in the yoga group will be lower than the control group.

H4: Posttest symptom frequency subscale scores of PSI in the yoga group will be lower than the control group.

H5: Posttest the limitations in activities of daily living subscale score of PSI in the yoga group will be lower than the control group.

Study Setting

The study was conducted with pregnant women who applied to antenatal care services at Farabi Hospital in the west of Turkey, between June 2018 and October 2018. This hospital was preferred because it serves different socioeconomic and sociocultural populations and has the necessary equipment (such as yoga mats, blocks, and bolsters).

Participants

The study population comprised 163 pregnant women attending antenatal care services between June 2018 and October 2018. The inclusion criteria for the study sample were as follows: (1) between 18 and 35 years of age, (2) 20 and 36 weeks of gestation, (3) singleton pregnancy, (4) not using medication or any TCM, (5) not doing exercise (90–150 min at 3 days a week), (6) not being diagnosed with chronic diseases (such as diabetes, hypertension, and thyroid), (7) not being diagnosed with risky pregnancy (such as premature rupture of membranes, placenta previa, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes), and (8) no disability for doing yoga by a physician's examination result.

Sample Size

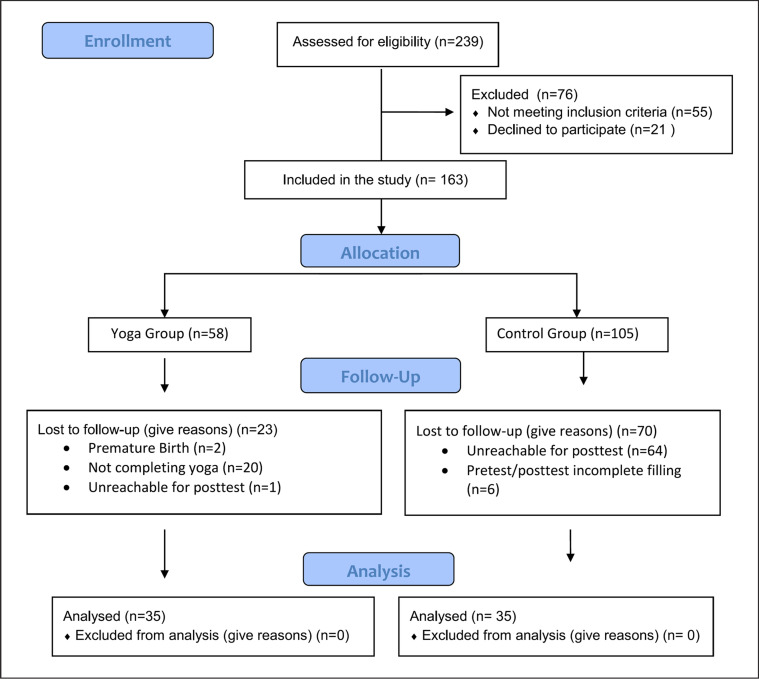

Power analysis was performed using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2) to determine the number of samples (power = 0.80; alpha = 0.05; symptom improvement rate 5%). It was determined that a sample size of 27 participants (for each group) would be sufficient to detect significant differences. Initially considering possible losses, 239 pregnant women were reached. It was determined that only 163 out of 239 pregnant women met the inclusion criteria. Pregnant women were divided into two groups, yoga (n = 58) and control (n = 105), using a simple random sampling method [23]. During the study, ninety-three pregnant women (yoga group: 23; control group: 70) were withdrawn/excluded. The study was completed with 70 pregnant women (yoga group: 35; control group: 35) (Fig. 1). In the post hoc power analysis made after the study, the study's power according to experimental and control group posttest comparison was 0.89.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Interventions

Prenatal Yoga Program

The researchers based the prenatal yoga program on relevant literature [9, 12, 13, 18, 19, 20, 24]. The prepared program was presented to the opinion of another yoga expert, and it was finalized. The prenatal yoga program includes meditation, asanas, pranayama, and savasana (online supplement 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000528801). The prenatal yoga program was done by the researcher (ESS) in the hospital, in groups of 6–10 pregnant women, for 4 weeks, once a week for 60 min. The researcher used an approach that included visual demonstration, verbal guidance, and hands-on assistance to practice prenatal yoga. The researcher (ESS) underwent Hatha yoga training for 200 h and prenatal yoga training for 100 h and had been practising yoga professionally for 7 years.

Procedures Applied to the Yoga Group

The researchers explained the study's aim and invited pregnant women to the study. Pregnant women who agreed to participate in the study and met the inclusion criteria signed a consent form. The days and hours of the prenatal yoga program were shared with the participants in the yoga group. The yoga group received the prenatal yoga program. In addition, the yoga group received the routine care recommended by the health ministry. As part of routine care, in the first follow-up of pregnant women who presented to the antenatal care services for pregnancy follow-up, a risk assessment form was used, and we planned how to conduct the follow-up. At least four quality follow-ups were planned for pregnant women with no risk based on prenatal care protocol: the first follow-up during the first 14 weeks; the second follow-up between weeks 18 and 24; the third follow-up between weeks 30 and 32; and the fourth follow-up between weeks 36 and 38. The participants were asked to fill out the PSI on the first day of the prenatal yoga program. Three days after the participants completed the 4-week prenatal yoga program, they were called by the researchers and asked to fill out the PSI again.

Procedures Applied to the Control Group

The control group only received routine care recommended by the ministry of health. Pretest data were obtained from the control group at the antenatal care service visit, and posttest data were obtained by calling four weeks later by phone.

Data Collection

In this study, the data were recorded by the researcher during face-to-face interviews with the participants, each lasting 10–15 min. The daily routines of the participants were not interfered with at any point in the study. The Descriptive Characteristics Form and Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory (PSI) scales were filled in for the members of both the yoga and the control groups as pretest. Four weeks after the beginning of the study, the participants were asked to respond to the PSI scale once again.

Outcome Measures

The data for this study were collected through face-to-face interviews using the Descriptive Characteristics Form and PSI.

Descriptive Characteristics Form

The descriptive characteristics form was created based on literature to reveal the descriptive characteristics of participants [25, 26]. It consists of 21 structured questions related to sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics.

Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory

The PSI was developed in 2013 [2]. PSI's Turkish validity and reliability were done at Turkey [27]. The inventory has 42 symptoms and two sections. The first section assesses the prevalence of pregnancy-related symptoms with a four-point Likert-type scale. The total score of the first section ranges from 0 to 126, with higher scores indicating a higher prevalence of pregnancy-related symptoms. The second section assesses the limiting effect of pregnancy-related symptoms on activities of daily living with a three-point Likert-type scale. The total score of the second section ranges from 42 to 126, with higher scores indicating a higher prevalence of limitations to activities of daily living [2, 27]. PSI symptoms are classified and evaluated according to the systems with which they are associated [28]. This study categorized the PSI symptoms as reproductive system symptoms (such as increased vaginal discharge and changes in libido), gastrointestinal system symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation), cardiovascular system symptoms (such as heart palpitations), respiratory system symptoms (such as snoring and shortness of breath), skin symptoms (such as greasy skin/acne and brownish marks on the face), neurological system symptoms (such as leg cramps and carpal tunnel), mental health symptoms (such as poor sleep and restless legs), urinary system symptoms (such as urinary frequency and incontinence), musculoskeletal symptoms (such as back pain and hip or pelvic pain), and tiredness [28]. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.82 [27] in the Turkish validity and reliability study and 0.89 in this study.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS 20.0 (Statistical Program for the Social Sciences). The descriptive statistics were given as number of units (n), percentage (%), and median (Q1–Q3). The concordance of the numerical data to the normal distribution was evaluated by means of the Shapiro-Wilk test. The comparison of categorical variables was made using the χ2 analysis. The comparison of the two independent groups was made using the Mann-Whitney U test, and the evaluation of two consecutive measurements was done using the Wilcoxon test. The comparison of the two dependent groups was made using the dependent samples t test. In these comparisons, a value of p < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. This study was reported according to the Consensus-Based Checklist Standardising the Reporting of Interventions for Yoga (CLARIFY) guidelines [29] (online supplement 2).

Results

The yoga and control groups had a mean age of 27.20 ± 3.40 and 27.80 ± 3.70 years, respectively. In addition, the groups had similar demographic characteristics. However, the yoga group (85.70%) had a significantly higher rate of primiparas than the control group (62.90%). The groups' sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics are presented in Table 1. The yoga and control groups had similar mean pretest PSI Symptom Frequency Total Scores (38.42 ± 18.76 to 38.88 ± 15.73) and other symptom scores (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics

| Yoga group (n = 35) X±SD | Control group (n = 35) X±SD | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 27.20±3.40 | 27.80±3.70 | ||

| Gestational week | 29.31±4.30 | 30.05±4.20 | ||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education, degree | ||||

| Primary school | 3 | 8.60 | 9 | 25.70 |

| High school | 11 | 31.40 | 5 | 14.30 |

| Bachelor's or higher | 21 | 60.00 | 21 | 60.00 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 11 | 31.40 | 15 | 42.90 |

| Unemployed | 24 | 68.60 | 20 | 57.10 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Normal | 13 | 37.10 | 10 | 28.60 |

| Overweight | 19 | 54.30 | 20 | 57.10 |

| Obese | 3 | 8.60 | 5 | 14.30 |

| Parity | ||||

| Primiparous | 30 | 85.70 | 22 | 62.90 |

| Multiparous | 5 | 14.30 | 13 | 37.10 |

| Planned pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 88.60 | 28 | 80.00 |

| No | 4 | 11.40 | 7 | 20.00 |

|

| ||||

| Total | 35 | 100.00 | 35 | 100.00 |

Analyzed by t test and x2 test. SD, standard deviation. *p < 0.05.

Table 2.

Intra-group pretest and posttest PSI Symptom Frequency Scores' comparison

| Systems scores | Yoga group (n = 35) |

Control group (n = 35) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest X±SD median |

Posttest X±SD median |

p value | Pretest X±SD median |

Posttest X±SD median |

p value | |||

| Genitourinary system | 5.91±3.68 5 | 5.22±3.21 5 | −0.82* | 0.40 | 6.22±3.23 6 | 5.80±2.62 6 | −0.44* | 0.65 |

| Cardiovascular system | 3.91±2.92 3 | 3.22±2.27 3 | −1.29* | 0.19 | 3.74±2.68 4 | 4.25±2.67 4 | −0.96* | 0.33 |

| Skin | 2.65±2.26 2 | 2.57±2.32 2 | −0.017* | 0.98 | 2.14±2.07 2 | 2.80±2.19 2 | −1.9** | 0.057 |

| Neurological system | 4.05±2.35 4 | 3.40±2.48 3 | −1.52* | 0.12 | 3.80±2.89 3 | 4.28±2.80 4 | −0.84* | 0.40 |

| Urinary system | 2.62±1.26 2 | 2.68±1.47 3 | −0.45* | 0.64 | 2.74±1.40 3 | 3.28±1.56 3 | −1.85* | 0.06 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 2.25±1.85 2 | 2.54±1.77 2 | −0.93* | 0.34 | 2.48±1.91 2 | 2.74±2.13 2 | −0.43* | 0.66 |

| Tiredness | 1.68±0.79 2 | 1.54±0.88 2 | 0.93* | 0.34 | 1.85±0.87 2 | 1.74±0.98 2 | −0.66* | 0.50 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 6.74±4.32 5 | 5.31±3.38 5 | −2,39** | 0.01*** | 7.14±3.82 7 | 6.65±4.55 5 | −0.56* | 0.57 |

| Respiratory system | 1.48±1.26 1 | 1.05±1.13 1 | −2.16** | 0.03*** | 1.45±1.42 1 | 1.62±1.37 1 | −0,72* | 0.47 |

| Mental health | 7.08±4.59 6 | 5.22±3.48 5 | −2.76** | 0.004*** | 7.28±4.12 6 | 7.34±4.02 7 | −0.42* | 0.67 |

| Symptom Frequency Total Score | 38.42±18.76 35 | 32.77±16.55 36 | 2.16** | 0.038*** | 38.88±15.73 39 | 40.48±18.32 39 | −0.57** | 0.56 |

PSI, Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

Analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Analyzed with the dependent (associated) groups t test.

p < 0.05.

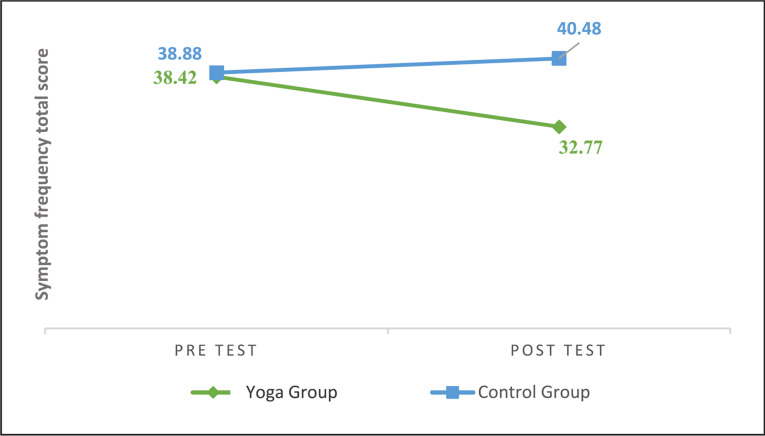

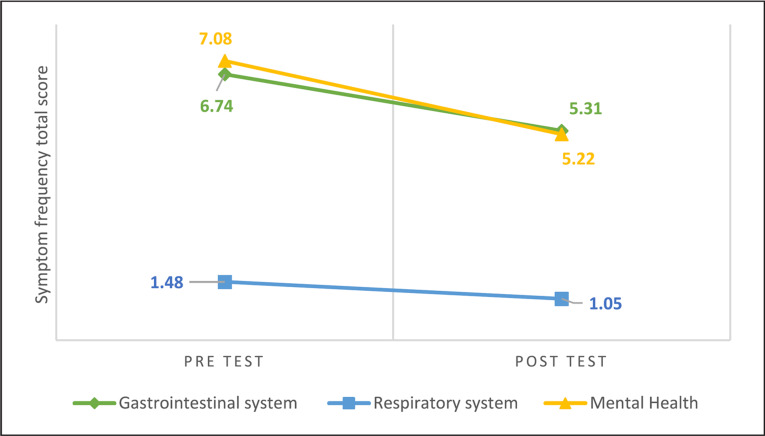

After the intervention, the yoga group had a significantly lower PSI Symptom Frequency Total Score (p = 0.038) (Fig. 2). Additionally, the yoga group had significantly lower gastrointestinal symptoms (p = 0.01), respiratory system symptoms (p = 0.03), and mental health symptoms subscale scores (p = 0.004) than the pretest scores (Fig. 3). However, there was no significant difference between the other subscale symptom scores (p > 0.05). In addition, there was no significant difference between the pretest and posttest PSI Symptom Frequency Total Scores and subscale scores in the control group (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory “Symptom Frequency Total Scores.”

Fig. 3.

Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory “Symptom Frequency Scores of Yoga Group.”

The yoga and control groups had a posttest PSI Symptom Frequency Total Score of 32.77 ± 16.55 and 40.48 ± 18.32. The yoga group had a significantly lower mean posttest PSI Mental Health Symptom Frequency Score than the control group (p = 0.0027). The groups had similar PSI Symptom Frequency Total Score (p = 0.069), genitourinary system (p = 0.25), gastrointestinal system (p = 0.28), cardiovascular system (p = 0.09), respiratory system (p = 0.08), skin symptoms (p = 0.52), neurological system (p = 0.18), urinary system (p = 0.13), musculoskeletal system (p = 0.79), and tiredness symptom (p = 0.30) scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pretest and posttest PSI Symptom Frequency Scores' comparison between groups

| Pretest |

Posttest |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yoga group (n = 35) |

control group (n = 35) |

yoga group (n = 35) | control group (n = 35) |

|||||

| X±SD median | X±SD median | p value | X±SD median | X±SD median | p value | |||

| Genitourinary system | 5.91±3.68 5 | 6.22±3.23 6 | −0.53* | 0.59 | 5.22±3.21 5 | 5.80±2.62 6 | −1.14* | 0.25 |

| Cardiovascular system | 3.91±2.92 3 | 3.74±2.68 4 | −0.10* | 0.92 | 3.22±2.27 3 | 4.25±2.67 4 | −1.66* | 0.09 |

| Skin | 2.65±2.26 2 | 2.14±2.07 2 | −1.00* | 0.31 | 2.57±2.32 2 | 2.80±2.19 2 | −0.63* | 0.52 |

| Neurological system | 4.05±2.35 4 | 3.80±2.89 3 | −0.81* | 0.41 | 3.40±2.48 3 | 4.28±2.80 4 | −1.31 * | 0.18 |

| Urinary system | 2.62±1.26 2 | 2.74±1.40 3 | −0.55* | 0.57 | 2.68±1.47 3 | 3.28±1.56 3 | −1.49* | 0.13 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 2.25±1.85 2 | 2.48±1.91 2 | −0.49* | 0.62 | 2.54±1.77 2 | 2.74±2.13 2 | −0.26* | 0.79 |

| Tiredness | 1.68±0.79 2 | 1.85±0.87 2 | −1.01 * | 0.31 | 1.54±0.88 2 | 1.74±0.98 2 | −1.03* | 0.30 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 5.91±3.68 5 | 7.14±3.82 7 | −0.55* | 0.57 | 5.31±3.38 5 | 6.65±4.55 5 | −1.06* | 0.28 |

| Respiratory system | 1.48±1.26 1 | 1.45±1.42 1 | −0.39* | 0.69 | 1.05±1.13 1 | 1.62±1.37 1 | −1.75* | 0.08 |

| Mental health | 7.08±4.59 6 | 7.28±4.12 6 | −0.23* | 0.81 | 5.22±3.48 5 | 7.34±4.02 7 | −2.3** | 0.0027*** |

| Symptom Frequency Total Score | 38.42±18.76 35 | 38.88±15.73 39 | −0.11 ** | 0.91 | 38.88±15.73 39 | 40.48±18.32 39 | −1.84** | 0.069 |

PSI, Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

Analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test.

Analyzed with the independent groups t test.

p < 0.01.

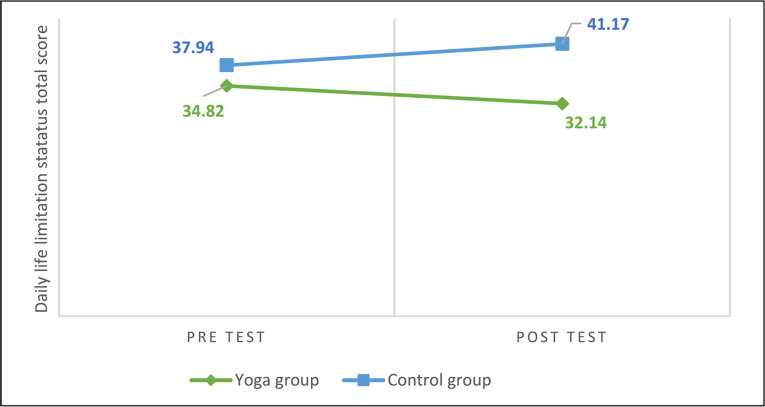

After the intervention, there was a significant difference in posttest PSI Limitations to Activities of Daily Living Total Scores between the yoga and control groups (p = 0.034) (Fig. 4) (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory “Limitations to Activities of Daily Living Total Scores.”

Table 4.

Pretest and posttest PSI Limitations to Activities of Daily Living Scores

| Pretest |

Posttest |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yoga group (n = 35) |

control group (n = 35) |

yoga group (n = 35) |

control group (n = 35) |

||||||||

| X±SD | median | X±SD | median t | p value | X±SD | median | X±SD | median | t | p value | |

| Limitations to Activities of Daily Living Total Score | 34.82±17.25 | 29 | 37.94±14.36 | 37 −0.82 | 0.41 | 32.14±16.40 | 30 | 41.17±18.53 | 38 | −2.15 | 0.034 * |

Analyzed by the independent sample t test. PSI, Pregnancy Symptoms Inventory; SD, standard deviation.

p < 0.05.

Discussion

This study's results show that prenatal yoga can reduce pregnancy-related symptoms, primarily gastrointestinal, respiratory, and mental health, and limiting effect of pregnancy-related symptoms on activities of daily living. The yoga and control groups had similar sociodemographic characteristics to other research in the literature [19, 30]. However, the yoga group had a higher rate of primiparas women than the control group, probably because primiparas are more interested in learning about pregnancy [31]. Considering the physiological changes in pregnancy, the symptoms and severity of pregnant women increase as the gestational week increases [25, 26]. In this study, the yoga group had a significantly lower posttest PSI Symptom Frequency Total Score than the pretest score. This result was similar to other studies in the literature [19, 30, 32]. Therefore, hypothesis H1 is accepted. Also, regarding the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and mental health symptoms, the posttest scores of the yoga group were significantly lower than the pretest scores, which supported the H2 hypothesis. It is included in the current literature that yoga causes physiological and neurophysiological changes by affecting the release of β-endorphins and neurotransmitters and provides relaxation by acting on the release of dopamine and serotonin, thus reducing stress [10, 15, 20]. Also, research shows that pregnant women who do yoga have lower stress, anxiety, depression, and fatigue [10, 15, 20, 33, 34]. In this study, yoga may have had a similar effect and reduced mental health symptom scores.

Stress significantly affects the emergence and severity of gastrointestinal system symptoms during pregnancy. Therefore, coping with stressors is essential in managing these symptoms [35, 36]. This study showed that yoga helped reduce mental health symptoms in the yoga group. Fewer gastrointestinal symptoms may have appeared after the intervention in the yoga group, as yoga positively affected stress and anxiety [10, 15, 20, 34, 37]. Yoga includes breathing exercises called pranayama [17], which affect biochemical and metabolic activities, neurocognitive abilities, and autonomic and pulmonary functions. Breathing through the right nostril increases the parameters associated with sympathetic activity, while breathing through the left nostril improves the parameters related to parasympathetic activity [38]. The nadi shodhana pranayama used in this study is associated with increased vagal tone and sympathetic activity. In contrast, ujjayi pranayama is associated with increased parasympathetic activity and reduced sympathetic activity by increasing baroreflex sensitivity [38]. In addition, pregnant women's need for oxygen increases, and carbon dioxide sensitivity decreases, resulting in hyperventilation during pregnancy. As pregnancy progresses, mechanical pressure from the uterus reduces functional residual capacity, and progesterone makes the airways hyperemic-edematous, causing breathing problems [25, 26]. Nadi shodhana and ujjayi pranayama may reduce hyperventilation, respiratory distress, and mental health symptoms by increasing parasympathetic activity. Also, ujjayi pranayama slows down exhalation, giving more time for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange and improving respiratory symptoms. In addition, regular pranayama may strengthen the respiratory muscles and help overcome breathing difficulties. In this study, the yoga group had a lower posttest respiratory system symptom score than the pretest score. This result supports the H2 hypothesis. There is evidence in the literature that pranayama and meditation reduce respiratory symptoms [39]. However, there was no difference in the posttest PSI Symptom Total Scores between the groups. Therefore, the H3 hypothesis was rejected. This may be due to ethnic differences or the duration and frequency of yoga practice. In addition, the yoga group had a lower mental health symptom score than the control group. This result supported the H4 hypothesis. The positive effects of yoga on stress, anxiety, and depression may have led to this result [10, 15, 20, 33, 34].

Generally, pregnant women prefer TCM to improve their health and well-being [3, 6]. In this study posttest, the limitations in activities of daily living subscale scores of PSI in the yoga group were lower than in the control group. Therefore, the H5 hypothesis was accepted. The fact that the yoga group experienced fewer respiratory, gastrointestinal, and mental health symptoms after the intervention may have contributed to this result. By reducing pregnancy-related symptoms, yoga may have reduced the limiting effect of symptoms on activities of daily living. Studies in the literature show that yoga improves the quality of life [33, 37]. With this aspect, prenatal yoga also meets the reason pregnant women prefer TCM [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 40].

Limitations

The results are sample-specific and cannot be generalized to all pregnant women. This study had some limitations. First, this study was not a randomized controlled study design. Therefore, there is the potential for observer bias. Second, the control group participants were less interested in remaining in the study than the yoga group because they received routine care. Therefore, dropout was higher in the control group. In addition, since it is a study during a changeable period, such as pregnancy, and requires follow-up, the follow-up loss is also high. Third, the posttests collected by calling both groups can be considered a study limitation.

Conclusion

Prenatal yoga can decrease the prevalence of gastrointestinal, respiratory, and mental health symptoms and reduce the limiting effect of pregnancy-related symptoms on activities of daily living. Therefore, nurses could recommend yoga sessions to pregnant women to cope with pregnancy-related symptoms. In addition, researchers could perform randomized controlled studies to investigate the effects of prenatal yoga on the quality of life of pregnant women. Researchers interested in prenatal yoga are recommended to study with larger samples with different sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the Marmara University Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 02/03/2018 and No 09.2018.215). Written consent was obtained from Farabi Hospital to conduct research. Participants were informed about the purpose and procedure of the study before participation and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without explanation. Informed consent was obtained from participants with the Voluntary Informed Consent Form. All stages of the study were conducted according to the ethical principles set by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was not registered in a clinical trial registry, so it has no clinical trial number.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding was received for any stages of the study.

Author Contributions

Eda Simsek Sahin designed the study, collected the data, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. Ozlem Can Gurkan designed the study, analyzed the data, and prepared the manuscript. We confirm that all listed authors meet the authorship criteria and that all authors agree with the manuscript's content.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and prenatal psychologist and yoga instructor Sibel Aydogmus for her supervision in creating the prenatal yoga program. The authors would also like to thank Midwifery Nevin Azak, who prepared the practice area for prenatal yoga.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for any stages of the study.

References

- 1.Alden KR. Anatomy and physiology of pregnancy. In: Lowdermilk DL, Perry SE, Cashion K, Alden KR, Olshansky EF, editors. Maternity & women's health care. 11th. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2016. pp. p. 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxcroft KF, Callaway LK, Byrne NM, Webster J. Development and validation of a pregnancy symptoms inventory. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13((1)):3–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman RL, Davis DL, Ferguson S, Taylor J. Women's motivation perception and experience of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy a meta-synthesis. Midwifery. 2018;59:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall HR, Jolly K. Women's use of complementary and alternative medicines during pregnancy a cross-sectional study. Midwifery. 2014;30((5)):499–505. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pallivalappila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, Pande B, Singh R, McLay JS. Complementary and alternative medicine use during early pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;181:251–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warriner S, Bryan K, Brown AM. Women's attitude towards the use of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2014;30((1)):138–143. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusof J, Mahdy ZA, Noor RM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy and its impact on obstetric outcome. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2016;25:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vardar-Yaglı N. Yoga during pregnancy and post-pregnancy. In: Akbayrak T, Ozgul S, editors. Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and post-pregnancy. 1st ed. Ankara: Hippocratic Publishing; 2020. pp. p. 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathfisch G. 1st ed. Istanbul: Ankara Nobel Medicine Bookstores; 2015. Yoga from pregnancy to motherhood; pp. p. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma A, Sharma R, Noheria S. Effects of prenatal yogic exercises on psychological parameters of pregnant women during 2nd and 3rd trimester. Asian Resonance. 2018;7((0976)):248–250. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrigan L, Eustace-Cook J, Moran P, Daly D. The effectiveness and characteristics of pregnancy yoga interventions a systematic review protocol. HRB Open Res. 2020 Jan;2:33. doi: 10.12688/hrbopenres.12967.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Yoga and social support reduce prenatal depression anxiety and cortisol. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2013;17((4)):397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Battle CL, Uebelacker LA, Magee SR, Sutton KA, Miller IW. Potential for prenatal yoga to serve as an intervention to treat depression during pregnancy. Women's Health Issues. 2015;25((2)):134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field T, Diego M, Delgado J, Medina L. Tai chi/yoga reduces prenatal depression anxiety and sleep disturbances. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19((1)):6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satyapriya M, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V, Nagendra HR. Effect of integrated yoga on anxiety depression & wellbeing in normal pregnancy. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19((4)):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuntharapat S, Petpichetchian W, Hatthakit U. Yoga during pregnancy effects on maternal comfort, labor pain and birth outcomes. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2008;14((2)):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar R. 1st ed. Delhi: Global Media: 2007. Yoga a gate way to curb social evils; pp. p. 65–105. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balaji PA, Varne SR. Physiological effects of yoga asanas and pranayama on metabolic parameters maternal and fetal outcome in gestationaldiabetes. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;7((6)):1–728. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun YC, Hung YC, Chang Y, Kuo SC. Effects of a prenatal yoga programme on the discomforts of pregnancy and maternal childbirth self-efficacy in Taiwan. Midwifery. 2010;26((6)):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusaka M, Matsuzaki M, Shiraishi M, Haruna M. Immediate stress reduction effects of yoga during pregnancy one group pre–post test. Women Birth. 2016;29((5)):82–8. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong K, Hwang H, Han H, Chae J, Choi J, Jeong Y, et al. Perspectives on antenatal education associated with pregnancy outcomes systematic review and meta-analysis. Women Birth. 2021;34((3)):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kwon R, Kasper K, London S, Haas DM. A systematic review the effects of yoga on pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020;250:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esin MN, Sampling . Research in nursing. In: Erdogan S, Nahcivan N, Esin MN, editors. 3rd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Medicine Bookstores; 2017. pp. p. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bershadsky S, Trumpfheller L, Kimble HB, Pipaloff D, Yim IS. The effect of prenatal hatha yoga on affect cortisol and depressive symptoms. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2014;20((2)):106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taskın L. 16th ed. Ankara Academic publishing; 2019. Obstetrics and women's health nursing; pp. p. 87–107. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gumussoy S, Kavlak O. Physiological changes in pregnancy. In: Sevil U, Ertem G, editors. Perinatology and care. 1st ed. İzmir: Ankara Nobel Medicine Bookstores; 2016. pp. p. 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Can-Gurkan O, Eksi-Guloglu Z. Turkish validity and reliability study of the pregnancy symptom ınventory. Acibadem University Journal of Health Sciences. 2020;11((2)):298–303. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gürkan ÖC, Ekşi Z, Deniz D, Çırçır H. The influence of intimate partner violence on pregnancy symptoms. J Interpers Violence. 2020;35((3–4)):523–541. doi: 10.1177/0886260518789902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moonaz S, Nault D, Cramer H, Ward L. Clarify 2021 explanation and elaboration of the Delphi-based guidelines for the reporting of yoga research. BMJ Open. 2021; Aug;11((8)):e045812. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rong L, Wang R, Ouyang YQ, Redding SR. Efficacy of yoga on physiological and psychological discomforts and delivery outcomes in Chinese primiparas. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;44:101434. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simkhada B, Teijlingen ERV, Porter M, Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61((3)):244–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holden SC, Manor B, Zhou J, Zera C, Davis RB, Yeh GY. Prenatal yoga for back pain, and maternal. wellness a randomized, controlled pilot study. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119870984. doi: 10.1177/2164956119870984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demir-Yıldırım A, Gungor-Satılmıs I. The effects of yoga on pregnancy, and anxiety. in infertile individuals a systematic review. Holist Nurs Pract. 2022;36((5)):275–283. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin IH, Huang CY, Chou SH, Shih CL. Efficacy of prenatal yoga in the treatment of depression and anxiety during pregnancy a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19((9)):5368. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19095368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuyama M, Takaishi O, Nakahara K, Iwakura N, Hasegawa T, Oyama M, et al. Associations among gastroesophageal reflux disease, psychological stress, and sleep. disturbances in Japanese adults. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52((1)):44–49. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1224383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Can-Gurkan O, Arslan H. Why do nausea and vomiting occur during pregnancy? Syndrome. 2006;18((10)):86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nadholta P, Bali P, Singh A, Anand A. Potential benefits of Yoga in pregnancy-related complications during the COVID-19 pandemic and implications for working women. Work. 2020;67((2)):269–279. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saoji AA, Raghavendra BR, Manjunath NK. Effects of yogic breath regulation a narrative review of scientific evidence. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2019;10((1)):50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hosseini Poor M, Ghorashi Z, Molamomanaei Z. The effects of yoga-based breathing techniques and meditation on outpatients' symptoms of COVID-19 and anxiety scores. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2022;9((3)):173. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hobek-Akarsu R, Kocak DY, Akarsu GD. Experiences of pregnant women participating in antenatal yoga a qualitative study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2022;28((4)):18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author