Abstract

The gene nmrA of Aspergillus nidulans has been isolated and found to be a homolog of the Neurospora crassa gene nmr-1, involved in nitrogen metabolite repression. Deletion of nmrA results in partial derepression of activities subject to nitrogen repression similar to phenotypes observed for certain mutations in the positively acting areA gene.

Fungi are capable of using a wide range of compounds as sources of nitrogen. Genes encoding enzymes and permeases required for nitrogen utilization are often regulated by specific induction mechanisms. In addition, they are usually subject to a general control mechanism, sometimes called nitrogen metabolite repression, according to which they are expressed at high levels only under conditions of nitrogen limitation. This enables readily assimilated nitrogen sources such as ammonium and glutamine to be used preferentially (for a review, see reference 26).

In all fungi investigated, a key feature of this regulatory mechanism is activation by regulatory proteins containing a DNA binding domain consisting of a four-cysteine, single zinc finger characteristic of the GATA family of transcription factors. In each case, loss-of-function mutations in the genes encoding these GATA factors result in reduced ability for growth on many different sole sources of nitrogen. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has two genes, GLN3 and NIL1/GAT1, while in other fungi only a single gene has been found: nit-2 in Neurospora crassa, areA in Aspergillus nidulans, nut1 in Magnaportha grisae, and nreA in Penicillium chrysogenum (4, 6, 17, 18, 21, 25, 27, 34, 36). The basic model for nitrogen metabolite repression is that growth in the presence of preferred nitrogen sources results in the generation of one or more signals which antagonize activation of gene expression by GATA factors. Under nitrogen-limiting conditions, the activators activate the expression of genes involved in the use of nitrogen sources.

In N. crassa, the gene nmr-1 has been found to be important for the response to nitrogen metabolite repression. Recessive mutations in this gene result in derepression of some nitrogen-controlled activities, suggesting a negative role for the gene (16, 31, 32, 37). Cloning and characterization of this gene have enabled studies of its role in nitrogen metabolite repression (19, 23, 24, 40). NIT2 and NMR1 were shown to interact by the use of the yeast two-hybrid system as well by in vitro assays. Two regions of NIT2 have been shown to be involved in interactions with NMR1, one in the conserved region adjacent to the zinc finger and one consisting of the 12 carboxyl-terminal residues. Mutations in both of these regions prevent interaction with NMR1 and result in derepressed phenotypes (39). These data strongly suggest that at least one component of nitrogen metabolite repression in N. crassa involves NMR1 interacting with NIT2 under nitrogen-sufficient conditions to prevent NIT2 binding to its recognition sequences and activating gene expression. Some in vitro binding studies support this model (39).

Extensive mutagenesis studies of areA in A. nidulans have shown that residues within the AreA DNA binding domain as well as in the carboxyl-terminal region lead to some degree of derepression for nitrogen-regulated activities (25, 29, 30, 35). In addition to the DNA binding domains, the carboxyl termini of NIT2, NreA and AreA, are highly conserved (29). Further, it has been shown that the deletion of sequences within the 3′ untranslated region of areA results in some derepression and that this correlates with a stabilization of areA mRNA in ammonium-grown mycelia (29). The sequences involved are conserved in the P. chrysogenum nreA homolog. The gene nit-2 has been shown to complement areA loss-of-function mutations in A. nidulans (12). However, partial derepression of the various nitrogen-regulated activities was observed. The nit-2 plasmid used may have lacked the necessary 3′ untranslated sequences (13). The xprD1 mutation, isolated as leading to derepression of protease expression (7), is an inversion truncating areA such that the 3′ coding and untranslated regions of the areA mRNA are missing (2, 25). Truncation of areA as in the xprD1 mutation would result in the loss of both mechanisms; this has been confirmed by the construction of appropriate double areA deletion mutations (29). Therefore there is strong evidence for two distinct mechanisms of modulation for areA and nit-2 activity, protein-protein interactions affecting DNA binding and nitrogen regulation of mRNA stability.

Although no mutants with the predicted phenotype have been isolated, the data lead to the strong prediction that A. nidulans has a homolog of nmr-1 of N. crassa. Expression of nmr-1 in A. nidulans suggests that this is the case (Polley and Caddick as cited in reference 26). We have confirmed this by cloning the nmr-1 homolog from A. nidulans and have found a central extended conserved region. Disruption of the gene results in partially derepressed phenotypes similar to those observed in areA mutants with alterations in the DNA binding domain and the carboxyl terminus.

Cloning and analysis of nmrA.

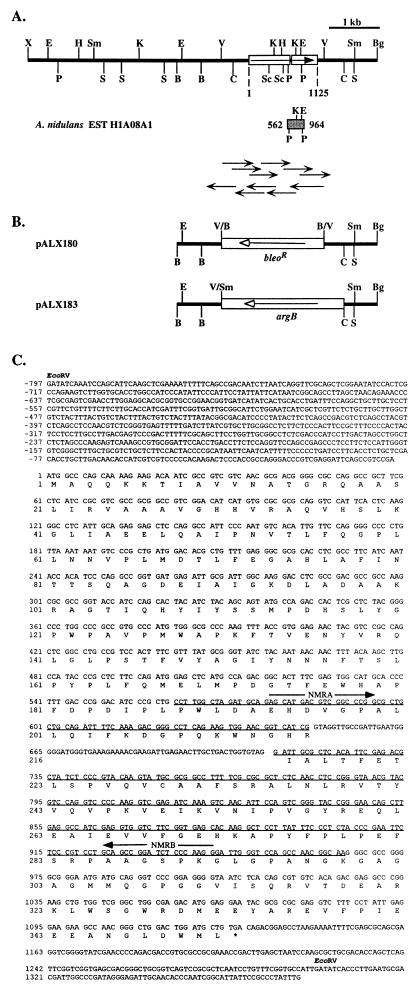

A search of the A. nidulans expressed sequence tag (EST) database (32a) with the N. crassa nmr-1 predicted protein sequence (accession no. P23762) revealed a sequence encoding a polypeptide fragment with extensive similarity. This allowed the design of primers for amplification from A. nidulans genomic DNA of a 383-bp sequence by PCR (Fig. 1A). Cloning and sequencing of this fragment confirmed homology with nmr-1 and the presence of a 68-bp intron. Southern blot analysis of A. nidulans genomic DNA indicated that the amplified sequence was unique and allowed the identification of a 7-kb XbaI-BglII hybridizing fragment. This fragment was cloned into XbaI-BamHI-digested pBLUESCRIPT SK+ (Stratagene, Inc.) by generating a partial genomic library and probing colony lifts with the PCR fragment. Restriction mapping confirmed that the arrangements of sites within the genome and the clone were identical (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Restriction map of the 7-kb XbaI-BglII fragment containing the gene nmrA. The two exons of the coding region (open rectangles) and the direction of transcription (arrow) are shown. The flanking coordinates of the open reading frame relative to the translational start are shown below the map. The location and coordinates of the EST (hatched rectangle) are shown. The gene nmrA was sequenced with a combination of dye primer and dye terminator reactions on an ABI 377 sequencer by the strategy shown, with the direction and size of the arrows indicating the strand and length of sequence. Restriction sites are BamHI (B), BglII (Bg), ClaI (C), EcoRI (E), EcoRV (V), HindIII (H), KpnI (K), PstI (P), SacI (Sc), SalI (S), SmaI (Sm), and XbaI (X). (B) Deletion constructs. pALX180, in which the EcoRV fragment spanning the entire coding region of nmrA as well as approximately 800 and 200 bp of 5′ and 3′ sequences, respectively, was replaced with an end-filled BamHI fragment containing the bleomycin resistance gene from pAmPh520 (3), and pALX183, in which the ClaI-EcoRV fragment spanning the entire coding region of nmrA as well as approximately 800 bp from both 5′ and 3′ sequences was replaced with a ClaI-SmaI fragment containing the A. nidulans gene argB (38). The flanking sequences (solid line) and selectable markers (open rectangles) and their direction of transcription (arrow) are shown. (C) Nucleotide and conceptual protein sequence of nmrA. The region encompassed by the EST (underlined) and the oligonucleotide primers NMRA and NMRB (arrow) used for the PCR-generated nmrA probe are shown. The two EcoRV restriction sites are marked for reference to the map in panel A. Nucleotides are numbered with reference to the +1 at the start of the coding region.

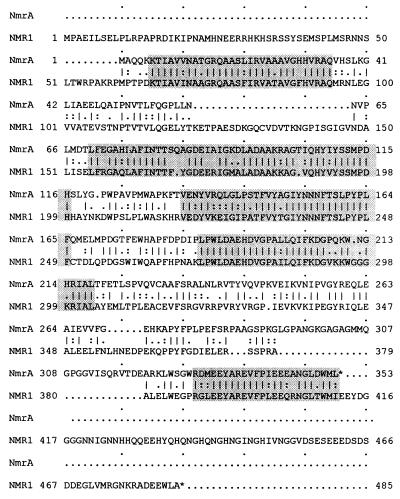

Sequence determination of 2,173 bp flanking the PCR fragment indicated an open reading frame encoding a 352-amino-acid polypeptide which is interrupted by a single intron (Fig. 1C). Comparison of the predicted polypeptide with that of N. crassa nmr-1 showed similarity extending throughout the sequence, with five regions of very high conservation (Fig. 2). However, the N. crassa sequence is extended at both the amino and carboxyl termini by 59 and 77 amino acids, respectively. It has been previously shown that the introduction of stop codons into nmr-1, leading to the loss of up to 77 carboxyl-terminal amino acids, does not appear to affect function, while function is abolished by the loss of 104 carboxyl-terminal amino acids (40). The former truncation removes all additional carboxyl-terminal amino acids of NMR1, while the latter removes the fifth highly conserved region between NMR1 and NmrA. In addition, protein-protein interaction studies have shown that the 45 amino-terminal amino acids of NMR1, not present in NmrA, are not required for binding to NIT2 and that the region from amino acids 118 to 284, spanning the three central conserved regions between NMR1 and NmrA, also binds NIT2, although the interaction is weaker (39). One insertion of 26 residues in NMR1 is not present in NmrA, and one insertion of 28 residues in NmrA is not present in NMR1. Inspection of the DNA sequences encoding these insertions indicate that they could have arisen by the mutation of intron splice sites (Fig. 1C) (40).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the A. nidulans NmrA and N. crassa NMR1 conceptual protein sequences. The alignment was generated with GAP from the Wisconsin package (version 8; Genetics Computer Group, Madison, Wis.) with the Dayhoff protein comparison weight matrix, a GAP weight of 3, and a length weight of 0.1. Identities between the two sequences are marked with vertical lines, and similarities are marked by colons. The five regions of highest identity are shaded. The two sequences show 60.8% identity and 75.5% similarity over their entire region.

Characterization of nmrA deletion strains.

Two different constructs were used to create nmrA deletions. In pALX180 the bleomycin resistance gene from Tn5 expressed from the N. crassa am promoter (3) replaced the nmrA sequence (Fig. 1). A linear SacI-KpnI fragment containing the nmrA::bleoR insert was used to transform A. nidulans MH3408 (biA1 amdS::lacZ niiA4), selecting for resistance to bleomycin. Approximately 20% of transformants showed some phenotypes characteristic of derepression of nitrogen-regulated activities (see below). In pALX183, argB (38) replaced the nmrA sequence (Fig. 1), and a NotI-KpnI fragment containing the nmrA::argB insert was used to transform A. nidulans MH8826 (yA1 pabaA1 argB1 amdA7), selecting for arginine prototrophy. Approximately 20% of transformants showed derepression phenotypes. Southern blot analysis of DNA isolated from transformants confirmed that, for each construct, the observed phenotypes correlated with replacement of nmrA sequences with bleoR or argB+ gene, respectively. One transformant from a single nmrA deletion event was isolated from each experiment and used for further characterization.

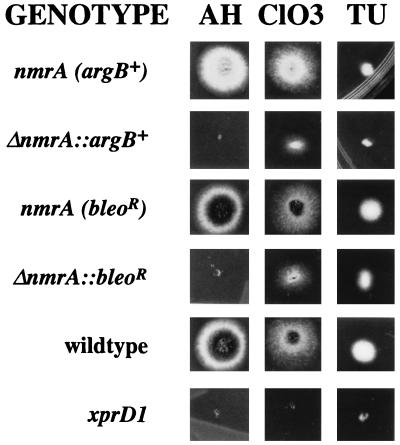

Various plate tests can be used to determine derepression of activities subject to nitrogen metabolite repression (reference 29 and references therein). The nmrA deletion transformants as well as an xprD1-containing strain were sensitive to the toxic effects of aspartylhydroxamate in the presence of ammonium, an indication of derepression of asparaginase (15) (Fig. 3). The nmrA deletion also resulted in slight sensitivity to thiourea in the presence of ammonium, but the sensitivity was not as great as that of the xprD1-containing strain (Fig. 3). Thiourea toxicity is an indicator of the activity of the ureA-encoded urea permease (28). Similarly, sensitivity to chlorate, a toxic analog of nitrate, in the presence of ammonium was observed in the nmrA deletion strain, but the sensitivity was intermediate between the xprD1 and wild-type strains (Fig. 3). Tests for derepression of extracellular protease production by the observation of a halo of clearing of milk (0.5 to 1.0%) in the presence of ammonium indicated that the nmrA deletion strains, unlike xprD1-containing strains, were not detectably derepressed. These phenotypes were similar to those observed by Platt et al. (29) for areA mutant strains encoding AreA proteins truncated at the carboxyl-terminal end but encoding mRNA with an intact 3′ untranslated region and indicated partial derepression for some activities.

FIG. 3.

Growth properties of nmrA deletion strains. Growth was scored for 2 to 3 days at 37°C on 1% glucose medium (9) containing 5 mM ammonium tartrate together with 200 mM potassium chlorate (ClO3), 5 mM ammonium tartrate together with 5 mM d,l-β-aspartylhydroxamate (AH), and 2.5 mM ammonium tartrate with 10 mM thiourea (TU) with appropriate auxotrophic supplements. The ΔnmrA::argB+ strain was generated by transformation of a strain whose genotype was yA1 pabaA1 argB1 amdA7 with a gel-purified insert of pALX183 selecting for arginine prototrophy (Fig. 1B). The nmrA+ (argB+) control strain was an ArgB+ transformant from the same transformation that did not result in the deletion of nmrA. The ΔnmrA::bleoR strain was obtained by transformation of a strain whose genotype was biA1 amdS::lacZ niiA4 with a gel-purified insert of pALX180 (Fig. 1B) selecting for resistance to bleomycin. The nmrA+ (bleoR) control strain was a bleomycin-resistant transformant from the same transformation that did not result in the deletion of nmrA. The genotypes of the strains designated wild type and xprD1 were biA1 and biA1 amdS::lacZ xprD1 niiA4, respectively. Genotypes and phenotypes were reported by Clutterbuck (5). The xprD1 mutation results from an inversion truncating the areA gene (2, 25).

The nmrA::argB deletion strain was transformed with the bleomycin resistance-encoding plasmid pAmPh520 (3) together with a plasmid (pALX186) containing nmrA on an EcoRV fragment (Fig. 1) and selecting for bleomycin resistance. Approximately 50% of the transformants were found to be phenotypically nmrA+ as shown by resistance to aspartylhydroxamate and chlorate in the presence of ammonium. This finding indicated that these phenotypes resulted from the deletion of nmrA and that this fragment is sufficient for nmrA function.

The gene amdS, encoding acetamidase, is subject to nitrogen metabolite repression (14). The deletion of nmrA was found to result in partial derepression of the expression of an amdS::lacZ reporter gene (11) with respect to both ammonium and glutamine (Table 1). Partial derepression was also observed in the presence of GABA as inducer, reflecting derepression of both amdS expression and GABA uptake via the gabA-encoded permease (1). Partial depression for nitrate reductase was also observed (Table 2), and the level of derepression was similar to that reported for the areA mutants encoding proteins truncated at the carboxyl terminus (29, 35).

TABLE 1.

Effect of nmrA deletions on nitrogen metabolite repression of amdS::lacZ expression

| Nitrogen sourcea | β-Galactosidase level (Miller units/min/mg of protein)b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmrA | % Dere- pressionc | ΔnmrA::bleoR | % Dere- pressionc | |

| Ala | 12.2 ± 1.3 | 13.7 ± 1.5 | ||

| NH4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 15 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 34 |

| Gln | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 20 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 46 |

| Ala + GABA | 91.2 ± 7.3 | 147.4 ± 16.0 | ||

| Ala + GABA + NH4 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 7 | 48.2 ± 10.1 | 33 |

Mycelium was grown for 16 h at 37°C in glucose minimal medium (9) containing in each case the following nitrogen sources: 10 mM l-alanine (Ala), 10 mM ammonium tartrate (NH4), 10 mM l-glutamine (Gln), and 10 mM γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA).

β-Galactosidase levels encoded by an amdS::lacZ translational fusion gene integrated by gene replacement at the amdS locus were assayed by the method of Davis et al. (11) and are expressed as means ± standard errors.

The percentage of derepression is calculated as the level of enzyme activity under repressed conditions relative to that under nonrepressed conditions: NH4 and Gln relative to the limiting nitrogen source Ala, Ala plus GABA plus NH4 relative to Ala plus GABA.

TABLE 2.

Effect of nmrA deletions on nitrogen metabolite repression of nitrate reductase expression

| Nitrogen sourcea | Nitrate reductase level (mU/min/mg of protein)b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmrA | % Dere- pressionc | ΔnmrA::argB | % Dere- pressionc | |

| NO3 | 66.5 ± 16.1 | 63.6 ± 11.2 | ||

| NO3 + NH4 | 6.2 ± 2.8 | 9 | 27.5 ± 6.3 | 43 |

| NO3 + Gln | 4.7 ± 0.5 | 7 | 28.7 ± 4.6 | 45 |

Mycelium was grown for 16 h at 37°C in glucose minimal medium (9) containing in each case the following nitrogen sources: 10 mM ammonium tartrate (NH4) and sodium nitrate (NO3).

Nitrate reductase levels were assayed by the method of Cove (9) and are expressed as means ± standard errors.

The percentage of derepression is calculated as the level of enzyme activity under repressed conditions relative to that under nonrepressed conditions: NO3 plus NH4 and NO3 plus Gln relative to NO3.

The areA102 mutation, resulting from an amino acid substitution in the zinc finger region, is a change in specificity mutation resulting in increased activation of some nitrogen-controlled activities and decreased activation of others (22, 25). A cross between the nmrA::bleoR deletion strain and an areA102 strain resulted in areA102 ΔnmrA::bleoR double mutants which showed increased sensitivity to chlorate and thiourea in the presence of ammonium relative to the ΔnmrA::bleoR single mutant and derepression for extracellular protease activity as shown by a halo of milk clearing in the presence of either ammonium or glutamine.

These results clearly indicate that one of the mechanisms for nitrogen metabolite repression is conserved between N. crassa and A. nidulans, namely protein-protein interactions between NMR1/NmrA and NIT2/AreA in the presence of sources of repression. The magnitude of the effects of deletion of nmrA on nitrogen metabolite repression is similar to that observed for deletion of the conserved 12 carboxyl-terminal amino acids of AreA (29). It is predicted that the effects of these mutations will not be additive in double mutants. Since deletion of nmrA does not result in complete derepression, this gene is unlikely to be involved in modulation of areA mRNA stability via sequences in the 3′ untranslated region (29). Therefore, it is predicted that double mutants containing an nmrA deletion and a deletion of the 3′ untranslated region of areA will show additive levels of derepression, as previously observed for the xprD1 inversion mutation and for areA mutants with deletions of both the carboxyl terminus and the relevant 3′ untranslated sequences (29).

The nature of the signal or signals generated by nitrogen metabolites and the question of whether both mechanisms have any common components remain to be determined. Furthermore, the role of negatively acting factors of the GATA family as found in S. cerevisiae (8, 10, 33), and recently suggested to occur in filamentous fungi (20), needs to be investigated.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence for the nmrA gene has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF041976.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council. Database and computer analysis was performed with the Australian National Genomics Information Service (ANGIS).

Assistance by Kathleen Soltys is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arst H N. Integrator gene in Aspergillus nidulans. Nature. 1976;262:231–234. doi: 10.1038/262231a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arst H N. A near terminal pericentric inversion leads to nitrogen metabolite derepression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;188:490–493. doi: 10.1007/BF00330054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Austin B, Hall R M, Tyler B M. Optimized vectors and selection for transformation of Neurospora crassa and Aspergillus nidulans to bleomycin and phleomycin resistance. Gene. 1990;93:157–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90152-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caddick M X, Arst H N, Taylor L H, Johnson R I, Brownlee A G. Cloning of the regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 1986;5:1087–1090. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clutterbuck A J. Aspergillus nidulans genetics. In: King R C, editor. Handbook of genetics. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corp.; 1974. pp. 447–510. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffman J A, Rai R, Cunningham T, Svetlov V, Cooper T G. Gat1p, a GATA family protein whose production is sensitive to nitrogen catabolite repression, participates in transcriptional activation of nitrogen-catabolic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:847–858. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen B L. Ammonium repression of extracellular proteases in Aspergillus nidulans. J Gen Microbiol. 1972;71:293–299. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coornaert D, Vissers S, Andre B, Grenson M. The UGA43 negative regulatory gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains both a GATA-1 type zinc finger and a putative leucine zipper. Curr Genet. 1992;21:301–307. doi: 10.1007/BF00351687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cove D J. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;113:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6593(66)80120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunningham T S, Cooper T G. Expression of the DAL80 gene, whose product is homologous to the GATA factors and is a negative regulator of multiple nitrogen catabolic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is sensitive to nitrogen catabolite repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6205–6215. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M A, Cobbett C S, Hynes M J. An amdS-lacZ fusion for studying gene regulation in Aspergillus. Gene. 1988;63:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90525-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis M A, Hynes M J. Complementation of areA− regulatory gene mutations of Aspergillus nidulans by the heterologous regulatory gene nit-2 of Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3753–3757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M A, Hynes M J. Why are nit-2 transformants of Aspergillus nidulans partially derepressed? Fungal Genet Newsl. 1997;44:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis M A, Kelly J M, Hynes M J. Fungal catabolic gene regulation: molecular genetic analysis of the amdS gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Genetica. 1993;90:133–145. doi: 10.1007/BF01435035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drainas C, Pateman J A. l-Asparaginase activity in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochem Soc Trans. 1977;5:259–261. doi: 10.1042/bst0050259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn-Coleman N S, Tomsett A B, Garrett R H. The regulation of nitrate assimilation in Neurospora crassa: biochemical analysis of the nmr-1 mutants. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:234–239. doi: 10.1007/BF00269663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Froeliger E H, Carpenter B E. NUT1, a major nitrogen regulatory gene in Magnaporthe grisea, is dispensable for pathogenicity. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:647–656. doi: 10.1007/BF02174113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu Y H, Marzluf G A. Molecular cloning and analysis of the regulation of nit-3, the structural gene for nitrate reductase in Neurospora crassa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8243–8247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu Y H, Young J L, Marzluf G A. Molecular cloning and characterization of a negative-acting nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;214:74–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00340182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas H, Angermayr K, Zadra I, Stoffler G. Overexpression of nreB, a new gata factor-encoding gene of Penicillium chrysogenum, leads to repression of the nitrate assimilatory gene cluster. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22576–22582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas H, Bauer B, Redl B, Stoffler G, Marzluf G A. Molecular cloning and analysis of nre, the major nitrogen regulatory gene of Penicillium chrysogenum. Curr Genet. 1995;27:150–158. doi: 10.1007/BF00313429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hynes M J. Studies on the role of the areA gene in the regulation of nitrogen catabolism in Aspergillus nidulans. Aust J Biol Sci. 1975;28:301–313. doi: 10.1071/bi9750301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarai G, Marzluf G A. Analysis of conventional and in vitro generated mutants of nmr, the negatively acting nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:233–420. doi: 10.1007/BF00633823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarai G, Marzluf G A. Generation of new mutants of nmr, the negative-acting nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa, by repeat induced mutation. Curr Genet. 1991;20:283–288. doi: 10.1007/BF00318516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kudla B, Caddick M X, Langdon T, Martinez-Rossi N M, Bennett C F, Sibley S, Davies R W, Arst H N. The regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mutations affecting specificity of gene activation alter a loop residue of a putative zinc finger. EMBO J. 1990;9:1355–1364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marzluf G A. Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:17–32. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.17-32.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minehart P L, Magasanik B. Sequence and expression of GLN3, a positive nitrogen regulatory gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encoding a protein with a putative zinc finger DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:6216–6228. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.12.6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pateman J A, Dunn E, Mackay E M. Urea and thiourea transport in Aspergillus nidulans. Biochem Genet. 1982;20:777–790. doi: 10.1007/BF00483973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Platt A, Langdon T, Arst H N, Kirk D, Tollervey D, Sanchez J M, Caddick M X. Nitrogen metabolite signalling involves the C-terminus and the GATA domain of the Aspergillus transcription factor AREA and the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNA. EMBO J. 1996;15:2791–2801. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platt A, Ravagnani A, Arst H N, Kirk D, Langdon T, Caddick M X. Mutational analysis of the C-terminal region of AREA, the transcription factor mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;250:106–114. doi: 10.1007/BF02191830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Premakumar R, Sorger G J, Gooden D. Nitrogen metabolite repression of nitrate reductase in Neurospora crassa. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:1119–1126. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1119-1126.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Premakumar R, Sorger G J, Gooden D. Physiological characterization of a Neurospora crassa mutant with impaired regulation of nitrate reductase. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:542–551. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.2.542-551.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Roe, B. A., D. Kupfer, S. Clifton, and R. A. Prade. Aspergillus nidulans cDNA Sequencing Project. URL http://www.genome.ou.edu/asper.html.

- 33.Soussi-Boudekou S, Vissers S, Urrestarazu A, Jauniaux J C, Andre B. Gzf3p, a fourth GATA factor involved in nitrogen-regulated transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1157–1168. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3021665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stanbrough M, Rowen D W, Magasanik B. Role of the GATA factors Gln3p and Nil1p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the expression of nitrogen-regulated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9450–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stankovich M, Platt A, Caddick M X, Langdon T, Shaffer P M, Arst H N. C-terminal truncation of the transcriptional activator encoded by areA in Aspergillus nidulans results in both loss-of-function and gain-of-function phenotypes. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart V, Vollmer S J. Molecular cloning of nit-2, a regulatory gene required for nitrogen metabolite repression in Neurospora crassa. Gene. 1986;46:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90414-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomsett A B, Dunn-Coleman N S, Garrett R H. The regulation of nitrate assimilation in Neurospora crassa: the isolation and genetic analysis of nmr-1 mutants. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:229–233. doi: 10.1007/BF00269662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Upshall A, Gilbert T, Saari G, O’Hara P J, Weglenski P, Berse B, Miller K, Timberlake W E. Molecular analysis of the argB gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol Gen Genet. 1986;204:349–354. doi: 10.1007/BF00425521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao X, Fu Y H, Marzluf G A. The negative-acting NMR regulatory protein of Neurospora crassa binds to and inhibits the DNA-binding activity of the positive-acting nitrogen regulatory protein NIT2. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8861–8868. doi: 10.1021/bi00027a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young J L, Jarai G, Fu Y H, Marzluf G A. Nucleotide sequence and analysis of NMR, a negative-acting regulatory gene in the nitrogen circuit of Neurospora crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;222:120–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00283032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]