INTRODUCTION

The use of recreational drugs has reached epidemic proportions in many countries and threatens to overwhelm economic, social, and health care systems. It is estimated that almost 1 in 4 people in developed countries have used recreational drugs at some time during their life. It is therefore inevitable that many doctors will have to manage and treat the ill effects associated with the abuse of these drugs.

In addition to their effects on the central nervous system, many of these agents induce profound changes in the heart and circulation that are responsible for a significant proportion of drug-related morbidity. This article reviews the cardiovascular complications associated with some of the commonly used recreational drugs.

Summary points

The abuse of recreational drugs is common and it is inevitable that doctors will have to manage and treat their associated ill effects

Recreational drugs are complex and can induce profound changes in cardiovascular function, both acute and chronic

Recreational drugs are often taken together, which can result in complex synergistic interactions with potentially detrimental effects

A high index of suspicion with early intervention and management is often the key to successful treatment

METHODS

Data were obtained by electronically searching MEDLINE, Embase, Poisindex (Micromedex Healthcare Series 2000), and standard textbooks of pharmacology and toxicology. Specific drugs or their chemical names were used as the main search term.

DRUGS AND SUBSTANCES

Cocaine, amphetamine, and ecstasy

Pharmacology

Cocaine, amphetamine, and ecstasy all share similar adverse effects on the cardiovascular system, related predominantly to sympathetic nervous system activation. Cocaine and its free-base form crack act by inhibiting the re-uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine at sympathetic nerve terminals. Circulating catecholamine concentrations can be elevated as much as 5-fold in cocaine users.1 At high doses, cocaine can impair myocyte electrical conduction and contractility.1

Amphetamine and its derivative ecstasy produce indirect sympathetic activation by releasing norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin from central and autonomic nervous system terminals.

Table 1.

| Suggested mechanisms by which cocaine, amphetamine, and ecstasy can cause hypotension |

|---|

|

Clinical effects

Sympathetic activation can lead to varying degrees of tachycardia, vasoconstriction, unpredictable blood pressure effects, and arrhythmias, depending on the dose taken and the presence or absence of coexisting cardiovascular disease.

Blood pressure changes

The high levels of circulating catecholamines and sympathetic activation commonly cause hypertension. However, hypotension can also occur (see box).2

Myocardial ischemia and infarction

Cocaine and amphetamine can cause myocardial ischemia and infarction in patients with or without coronary artery disease. The mechanism is uncertain, but may be related to the elevated catecholamine concentration, which increases myocardial oxygen demand, coronary artery spasm, platelet aggregation, and thrombus formation.2,3,4 Cocaine can produce a procoagulant effect by decreasing concentrations of protein C and antithrombin 3 and potentiating thromboxane production.2

Long-term use of cocaine and amphetamine can cause repetitive episodes of coronary spasm and paroxysms of hypertension, which may result in endothelial damage, coronary artery dissection, and acceleration of atherosclerosis.

Aortic dissection, valvular damage, and endocarditis

Paroxysmal increases in blood pressure can lead to aortic dissection or valvular damage that increases the risk of endocarditis affecting mainly left-sided cardiac structures.1 Endocarditis is often associated with unusual organisms such as Candida, Pseudomonas, or Klebsiella and frequently has an aggressive clinical course with marked valvular destruction, abscess formation, and a need for surgical intervention.

Cardiomyopathy

Prolonged administration of cocaine or amphetamines can also lead to a dilated cardiomyopathy.2 Etiologic mechanisms include repeated episodes of subendocardial ischemia and fibrosis and myocyte necrosis produced by exposure to excessive catecholamine concentrations, infectious agents, and heavy metal contaminants (manganese is present in some cocaine preparations).

Pulmonary edema and pulmonary hypertension

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and pulmonary hypertension can also occur with cocaine and amphetamine misuse, although the precise underlying mechanism remains unknown.

Arrhythmias

The adverse cardiovascular changes and sympathetic stimulation associated with cocaine and amphetamine ingestion predispose to myocardial electrical instability, precipitating a wide and unpredictable range of supraventricular and ventricular tachyarrhythmias. The presence of fibrotic scars, myocardial ischemia, and left ventricular hypertrophy can act as a substrate for arrhythmogenesis. Cocaine possesses class 1 antiarrhythmic properties (blocks sodium channels) and can impair cardiac conduction causing prolongation of the PR interval, QRS complex, and QT interval. Cocaine can also cause a wide range of bradyarrhythmias, including sinus arrest and atrioventricular block.

Pneumothorax and pneumopericardium

Cocaine inhalation in association with a forced Valsalva maneuver (the positive ventilatory pressure increases drug absorption and therefore enhances the drug effect) can rarely give rise to a pneumothorax or pneumopericardium.

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin (“magic mushrooms”)

Pharmacology

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin are commonly used hallucinogenic agents that are structurally related and have similar physiologic, pharmacologic, and clinical effects. LSD is about 100 times more potent than psilocybin. Their mechanisms of action are complex with various agonist, partial agonist, and antagonist effects at serotonergic, dopaminergic, and adrenergic receptors.2

Clinical effects

The adrenergic effects of these drugs are usually mild and can give rise to general sympathetic arousal leading to dilated pupils, tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperreflexia. Although cardiovascular complications are rarely serious, supraventricular tachyarrhythmias and myocardial infarction have been reported.5 Changes in serotonin-induced platelet aggregation and sympathetically induced arterial vasospasm may have been contributory factors leading to the onset of myocardial infarction.5

Narcotic analgesics

Pharmacology

Morphine and its semisynthetic analogue heroin are the most commonly used recreational narcotic drugs. Narcotic agents act centrally on the vasomotor center to increase parasympathetic and reduce sympathetic activity.

Clinical effects

These autonomic changes, combined with histamine release from mast cell degranulation, can result in bradycardia and hypotension. Cardiac arrhythmias—including premature atrial and ventricular ectopic activity, atrial fibrillation, idioventricular rhythm, and ventricular tachyarrhythmias—have all been reported.2 Bacterial endocarditis, affecting mainly right-sided cardiac structures, is a well-known complication of intravenous narcotic drug abuse, and it is sometimes associated with pulmonary abscesses. Heroin overdose can cause noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, the onset of which can be delayed for up to 24 hours after admission.6 A disruption in alveolar-capillary membrane integrity has been suggested as a mechanism.

Volatile substance abuse

The abuse of volatile substances is an increasing problem among young male adolescents. The products used are legal, cheap, and easily available. Following inhalation, feelings of euphoria, excitement, and invulnerability can occur rapidly, but are short-lived.

Clinical effects

Cardiac arrhythmias are presumed to be the main cause of death from volatile substance abuse. Volatile substances may induce supraventricular or ventricular tachyarrhythmias by sympathetic activation or by myocardial sensitization to circulating catecholamines.7 Some abusers spray the substances directly into the mouth, which can result in intense vagal stimulation and a reflex bradycardia. Profound bradycardia can evolve into asystole or secondary ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Some volatile compounds can reduce sinoatrial node automaticity, prolong the PR interval, and induce atrioventricular block.2 Myocardial ischemia and infarction have been reported and are believed to be caused by a combination of coronary vasospasm, hypoxia caused by the formation of carboxyhemoglobin or methemoglobinemia, or excessive sympathetic stimulation.2 Long-term misuse can induce a poorly characterized cardiomyopathy.8

Cannabis

Pharmacology

Cannabis has a biphasic effect on the autonomic nervous system, depending on the dose absorbed.3 Low or moderate doses can increase sympathetic and reduce parasympathetic activity, producing a tachycardia and an increase in cardiac output. In contrast, higher doses inhibit sympathetic and increase parasympathetic activity, resulting in bradycardia and hypotension. Reversible ECG abnormalities affecting the P and T waves and the ST segment have been reported.9 It is not clear whether these changes occurred as a direct result of cannabis, independent of its effect on the heart rate.

Clinical effects

Although supraventricular and ventricular ectopic activity can occur, life-threatening tachy- or bradyarrhythmias have not been reported. In patients with ischemic heart disease, cannabis increases the frequency of anginal symptoms at low levels of exercise. This occurs as a result of a drug-induced increase in heart rate and myocardial contractility that increases myocardial oxygen demand.2

CONCLUSION

The abuse of illegal drugs is endemic in society and has the potential to cause major acute changes in cardiovascular function and irreversible damage to the heart. These drugs are frequently taken together as “cocktails,” often in conjunction with alcohol. These combinations can have complex synergistic interactions, with potentially detrimental effects.

Many patients who present with complications will be unable or unwilling to provide a history of illegal drug use. Recreational drug use should always be suspected and looked for in patients presenting with unexplained or unusual cardiovascular disturbances associated with mood disturbances or central nervous system dysfunction. As drug misuse continues to permeate every level of society, it is inevitable that physicians will have to manage the devastating complications of these compounds. An awareness of the life-threatening cardiovascular effects, along with early diagnosis and intervention, is often the key to successful treatment.

Figure 1.

Recreational drug use has become more widespread

© Greg Smith/AP

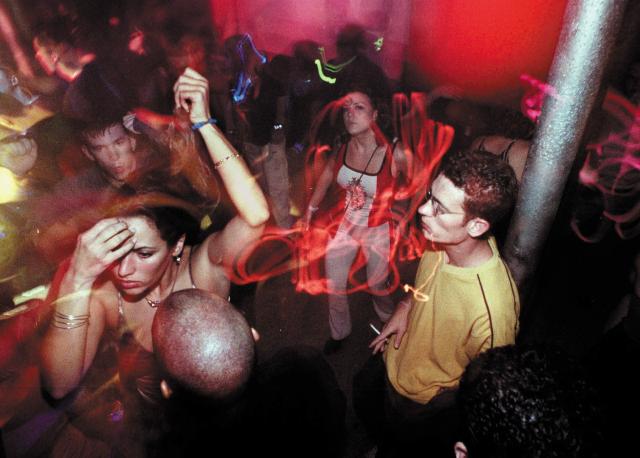

Figure 2.

Young people in nightclubs often take a cocktail of drugs and alcohol

© Greg Smith/AP

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Mouhaffet A, Madu E, Satmary W, Fraker T. Cardiovascular complications of cocaine. Chest 1995;107: 1426-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghuran A, Nolan J. Recreational drug misuse: issues for the cardiologist. Heart 2000;83: 627-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashour T. Acute myocardial infarction resulting from amphetamine abuse: spasm thrombus interplay. Am Heart J 1994;128: 1237-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heesch CM, Wilhelm CR, Ristich J, Adnane J, Bontempo FA, Wagner WR. Cocaine activates platelets and increases the formation of circulating platelet containing microaggregates in humans. Heart 2000;83: 688-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borowiak KS, Ciechanowski K, Waloszczyk P. Psilocybin mushroom (Psilocybe semlanceata) intoxication with myocardial infarction. Clin Toxicol 1998;36: 47-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osterwalder JJ. Patients intoxicated with heroin or heroin mixtures: how long should they be monitored? Eur J Emerg Med 1995;2: 97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flanagan RJ, Ives RJ. Volatile substance abuse. Bull Narc 1994;46: 49-78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman MN, Banim S. “Glue sniffer's” heart? BMJ 1987;294: 739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kochaar M, Hosko MJ. Electrocardiographic effects of marijuana. JAMA 1973;225: 25-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]