Abstract

Background

Okhaldhunga is a hilly district with fragile socioeconomic conditions, limited access to health care, social stigma, and poor resource management, where most people rely on medicinal plants for primary health care. The use of medicinal plants for primary health care varies with socioeconomic attributes. Following the intra-cultural analysis, we documented and tested the hypothesis that use of medicinal plants in Champadevi, Okhaldhunga, Nepal, depends on socioeconomic variables.

Methods

We interviewed 224 respondents, 53.12% female and 46.88% male, including 31 Brahmin, 157 Chhetri, 13 Dalit, and 23 Janajati, and conducted three focused group discussions and seven key informant interviews to record the ethnomedicinal plants used in Champadevi rural municipality, Okhaldhunga District. The relative frequency of citation (RFC) was computed to know the importance of the species. A generalized linear model (GLM) was used to see the relationship between medicinal plants reported with the sociocultural variables, which include age, gender, occupation, education, ethnicity, and religion.

Results

We documented 149 medicinal plants, including 69 herbs, 22 shrubs, nine climbers, 48 trees, and one parasitic plant, belonging to 68 families and 130 genera, and used to treat 48 distinct diseases and ailments. Plant parts, leaf, and digestive disorders were frequently treated during healing. Curcuma angustifolia was the most cited species with RFC 0.9554. The respondents' knowledge of medicinal plant use varied significantly with age (p = 0.0001) and occupation (p = 0.003). Changes in land use, population decline of medicinal plant species, and unsustainable harvesting practices constituted the local threats to medicinal plants and associated knowledge. Elders died without passing on their knowledge to the younger generations during sociocultural transformation, and youth disinterest coupled with the free availability of allopathic medicine led to knowledge erosion.

Conclusions

The use of medicinal plants in Champadevi, Okhaldhunga, was significantly depended on two socioeconomic variables age and occupation. Ethnomedicinal plants are essential in the primary healthcare system in Nepal; however, their availability and practices are declining. Thus, plans regulating land use change and human migration, acknowledging traditional healthcare practices, and raising awareness of the significance of traditional medical practices as complementary healthcare practices should be strengthened.

Keywords: Intra-cultural analysis, Medicinal plants, Traditional uses, Sociocultural transformation, Okhaldhunga, Nepal

Introduction

From 1515 to 2331, useful medicinal and aromatic plants have been cataloged in Nepal [1–4]. These plants are frequently valued in rural areas for food, medicine, construction, fodder, and firewood. Rural livelihood is intrigued by folklore uses for the primary healthcare system [5]. The use of ethnomedicine in rural areas has been transmitted orally from one generation to the next [6], yet it has been threatened by sociocultural transformation [7], human migration, and the limited transfer and extension of ethnomedicinal knowledge [3]. Moreover, traditional and ethnomedical knowledge are sparingly documented [8]. Geography, ethnicity, age, occupation, education, and culture substantially impact traditional ethnomedical knowledge [9]. Assessment of the interaction between the variables of geography, socio-culture, and livelihood provides ample opportunity to conserve medicinal plant species and their associated knowledge [10]. Therefore, ethnomedicinal research is required to grow and maintain medicinal plants and their associated knowledge [11, 12].

Nepal is comprised of five disparate eco-physiographical regions: the Himalayas (23% of the total area and above 5000 m asl), the High Mountains (20%, between 3000 and 5000 m asl), the Middle Mountains (30%, between 1000 and 3000 m asl), the Siwalik Hills (12.8%, between 500 and 1000 m asl), and the flat, lowlands of Tarai (13.7%, < 500 m asl) [13]. The mid-hills and mountains are home to the greatest number of medicinal plants in Nepal and are associated with diverse ethnic groups [10]. Okhaldhunga is a hilly district with fragile socioeconomic conditions, limited access to health care, social stigma, and poor resource management [14]. It is one of the understudied districts, with few ethnomedicinal publications and records of the least-used medicinal plants [10, 15].

There is no any detail investigation and documentation of medicinal in Okhaldhunga as well as in Champadevi community; therefore, this study was carried out to document and catalogue the medicinal plant used by local people of Champadevi rural municipality, to analyze the distribution of use knowledge within the socioeconomic variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, education, religion, and occupation and to assess the challenges and threats constraining the population, use, and distribution of useful plants and their associated ethnomedicinal knowledge. We hypothesized that the use of medicinal plants in Champadevi rural municipality is related to socioeconomic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, education, religion, and occupation). This information on medicinal plant species is crucial for the conservation policy and implementation. Further, to promote traditional knowledge of Champadevi community people, help to promote their identity and help in medicine development.

Methodology

Study area

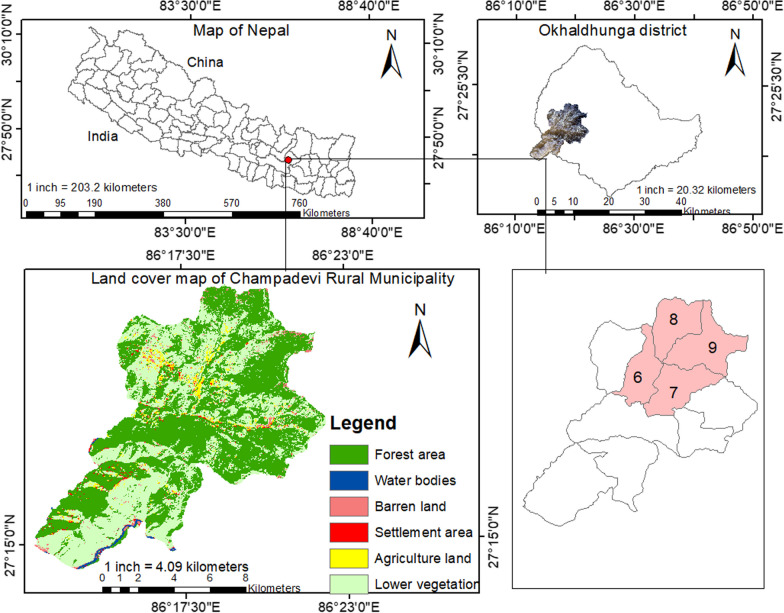

Okhaldhunga district has 53.34% ethnic (Janajati) people followed by Chhetri21.22%, Brahmin 9.19%), Dalit (15.38%), and others (0.87%) [16]. Champadevi rural municipality is one of the southwest rural municipalities of this district bordering south to Sindhuli and west to Ramechhap district, Koshi Province, eastern Nepal. The municipality's population was 16,528 as of the 2021 Census [16]. The municipality is divided into ten wards. For this study, we selected four wards (6, 7, 8, and 9) with 1399 households where we found several traditional healers (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area (Champadevi rural municipality with ward numbers 6, 7, 8, and 9)

Bhramin, Chettri, Dalit, and ethnic (Janajati) are the major ethnicity of the area. The ward numbers 6 and 7 are dominated by Chhettri, 8 has equal domination of both Chhetriand Janajati, and 9 is dominated by Janajati. People were following Hinduism and Buddhism. However, the dominated one is Hinduism. Most of the people are indigenous people of this area. The out migration rate is highest in ward numbers 8 and 9.

Champadevi village consists of mixed vegetation types. The land use of the area comprises human settlement and built-up areas (9.93%), forested areas (55.32%), barren land (5.67%), agricultural land (7.52%), water bodies (4.54%), and lower vegetation or shrubs (17.02%). Agriculture and livestock husbandry are the primary livelihood options. The primary energy source for cooking, heating, fodder, and firewood collection is nearby forests. The area is rich in traditional knowledge, and elders rural residents collect forest products and treat ailments using traditional methods. The health facility in the area is limited; people access district headquarters (Siddhicharan municipality) to treat health disorders.

Methods

Data collection

We adhered to the International Society of Ethnobiology's code of conduct [17]. Each respondent's verbal consent was obtained prior to the survey. The field visit occurred between July and November of 2021.

We obtained 210 or more than 210 households out of a total of 1399 households of Champadevi rural municipality ward numbers 6, 7, 8, and 9 to be surveyed following the online platform (https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html), keeping confidence level 95% with margin of error ± 5% and household proportion 20%. Therefore, we interviewed 224 respondents from different households of Champadevi rural municipality ward numbers 6, 7, 8, and 9 following stratified random sampling methods.The socioeconomic and demographic conditions of respondents along with the use and conservation of local medicinal plants were recorded. Three focused group discussions (eight to twelve respondents in each group) and interviews with seven key informants (four Dhami/Jhakri traditional healers and three Vaidhyas) were conducted to validate the information obtained from the discussions, interviews and informal meetings. There were several informal meetings held during evenings and mornings while staying and having tea in the tea-vendor houses. The selection of key informants was based on the references made by the respondents and village secretaries. A free list of valuable medicinal plants was compiled, validated, and verified using consensus of at least three local medicinal plant experts (Dhami/Jhakri traditional healers and Vaidhyas).

Demographic profile of the respondents

Among the 224 respondents surveyed, 105 were male (46.88%) and 119 were female (53.12%). The respondent's ages ranged from 20 to 90 years old. More than half of the respondents, 150 (66.97%), were between 20 and 59, while the remaining 74 (33.03%) were older than 60. Most respondents were Hindu (202; 90.18%) and held basic knowledge of education (137; 61.17%). Table 1 shows that most respondents were Chhetri (157; 70%), followed by Bhramin (31; 13.83%). The family's primary source of income was agriculture (176; 78.57%).

Table 1.

Demographic profile of the respondents

| Variables | Description | Total (n = 224) | Respondents frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20–29 | 24 | 10.71 |

| 30–39 | 36 | 16.07 | |

| 40–49 | 38 | 16.97 | |

| 50–59 | 52 | 23.21 | |

| 60–69 | 42 | 18.76 | |

| 70–79 | 24 | 10.71 | |

| 80–89 | 8 | 3.58 | |

| Gender | Male | 105 | 46.88 |

| Female | 119 | 53.12 | |

| Education | Primary | 68 | 30.35 |

| Secondary | 24 | 10.71 | |

| Higher secondary | 17 | 7.59 | |

| University | 18 | 8.03 | |

| Illiterate | 97 | 43.3 | |

| Occupation | Agriculture | 176 | 78.57 |

| Agri-business | 16 | 7.14 | |

| Services | 32 | 14.29 | |

| Ethnicity | Bhramin | 31 | 13.83 |

| Chhetri | 157 | 70.09 | |

| Dalit | 13 | 5.8 | |

| Janajati | 23 | 10.27 | |

| Religion | Hindu | 202 | 90.18 |

| Buddhist | 22 | 9.82 |

Plant collection and identification

Following Jain's [18] methodology, we gathered the voucher specimens for the final list. Each specimen was assigned the collection, place name, latitude, longitude, and code. Further consultations with plant taxonomists were conducted to verify the nomenclature of collected plant species. The identified specimens were compared to their originals at the National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH), Godawari, Lalitpur, Nepal. The voucher specimens with collection codes were submitted to the National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH), Godawari, Lalitpur, Nepal.

Land use change analysis

The Champadevi rural municipality land use classification map was extracted from the Nepal map for land use using GIS. Landsat-7ETM of 1999, Landsat-7ETM of 2010, and Landsat-7ETM of 2020 satellite images were downloaded freely from the US Geological Survey's (USGS) Earth Explorer website (http://earthexplorer.usgs.gov). Using ArcGIS 10.4, land use change was analyzed for 1999, 2010, and 2020. Supervised classification with a maximum likelihood classifier (MLC) was used for image classification and the preparation of base maps for detecting change [19]. An accuracy assessment was done following [20].

Quantitative and statistical analyses

Suitable quantitative methods and approaches were used in indices such as frequency of citation (FC) and relative frequency of citation (RFC) to enhance the indicative value of the ethnomedicinal study. Similar methods were used in hilly communities in India [21], whose characteristics resemble those of our study area. According to Tardio and Pardo-de-Santayana [22], the frequency of citation (FC) and relative frequency of citation (RFC) were computed.

where FC, number of respondents who mentioned the use of species; N, Total number of respondents who participated in a survey.

Diseases and ailments were grouped into 13 categories based on the International Classification of Primary Care (ICPC) [23]. Using a similarity index, the ethnomedicinal plants in this study and previous studies were compared [24, 25]. We compared our findings to other researchers from eastern Nepal [26–28].

where a, number of unique species in area A; b, number of species unique in area B; c, Number of common species in A and B; d, number of common species used for similar ailments in A and B areas.

While a & b ≠ 0 and c & d ≥ 0.

The Rahman's similarity index is used to show the cultural similarities of indigenous knowledge among the communities based on plant use knowledge [25].

Since the data of medicinal plants recorded per respondents were count data, to test the hypothesis that use of medicinal plants in Champadevi rural municipality is determined by socioeconomic variables (age, gender, ethnicity, education, religion and occupation), we used a generalized linear model (GLM) with quasi-Poisson options due to the over dispersion of the Poisson model in R 3.4.4 [29].

Results

We documented 149 plant species representing 68 families and 130 genera. Most species belonged to the Leguminosae, Solanaceae, and Zingiberaceae families, with seven species each. Moreover, the most prevalent genus was Allium, with four species, followed by Citrus, with three. Fever (30) was treated with the most species, followed by diarrhea (28), stomachache (22), and the common cold (22). Malaria (1), eye allergy (1), nose bleeding (1), and hematuria (1) were treated the least (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medicinal plant recorded with Family, scientific name, habit, parts, used, mode of use, FC and RFC

| Family | Scientific name | Local name | Habit | Parts used | Mode of use | Ailments | FC | RFC | Voucher code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Justicia adhatoda L | Asuro | Shrub | Leaves | Raw, powder | Body pain, cough, asthma, tuberculosis, headache, fever, pneumonia | 26 | 0.116 | 2022001 |

| Agaricacaeae | Agaricus campestris L | Chate Cyau | Herb | Whole plant | cooking, eating | Blood pressure, liver disorders, diabetes | 15 | 0.067 | 2022002 |

| Amaranthaceae | Achyranthes bidenata Blume | Dativan | Shrub | Stem, leaves | Chewing | Tooth | 0.031 | 2022003 | |

| Amaranthaceae | Amaranthus viridis L | Latte saag | Herb | Leaves | Cooking, eating | Body pain, urinary disorders, fever, asthma, liver, eye disorders | 3 | 0.013 | 2022004 |

| Amaranthaceae | Alternanthera sessilis (L.) DC | Bhirangi jhar | Herb | leaves | Juice, paste eating | Fever, wound | 1 | 0.004 | 2022005 |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium ascalonicum L | Chyapi | Herb | Leaves | Soup drinking | Pain relief | 6 | 0.027 | 2022006 |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium sativum L | Lasun | Herb | Bulb, leaves | boil with water, dried | High blood pressure, liver disorders, dysentry, intestinal worms, tuberculosis, diabetes, fever, gastric, common cold | 200 | 0.893 | 2022007 |

| Amaryllidaceae | Allium cepa L | Pyaj | Herb | Bulb leaves | Paste | Headache, hair growth | 45 | 0.201 | 2022008 |

| Amaryllidaceae | Crinum amoenum Roxb | Hare lasun | Herb | Leaves, bulb | Eating | Stomach, gastric | 37 | 0.165 | 2022009 |

| Amaryllidaceae | Zephyranthes candida Herb | Seto pyaj | Herb | Bulb leaves | Eating | Indigestion, gastric | 4 | 0.018 | 2022010 |

| Anacardiaceae | Spondias pinnata (L.f.) Kurz | Amaro | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Vomiting | 1 | 0.004 | 2022011 |

| Anacardiaceae | Mangifera indica L | Ampa | Tree | Leaves | Eating, paste | Stomach ache, fever | 23 | 0.103 | 2,022,012 |

| Anacardiaceae | Choerospondias axillaris (Roxb.) B.L. Brutt. &A.W. Hill | Lapsi | Tree | Seed | Burning seed powder | Burning wound | 1 | 0.004 | 2022013 |

| Apiaceae | Centella asiatica (L) Urb | Ghod tapre | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Uterus, urine infection, body pain, Upt | 17 | 0.076 | 2022014 |

| Apiaceae | Cuminum cyminum L | Jira | Herb | Seed | Raw | Common cold, fever, headache, stomach ache | 34 | 0.152 | 2022015 |

| Araceae | Colocasia antiqorum Schott.var.esculenta | Karkalo | Shrub | Whole plant | Cooking, eating | Diarrhea, body ache, iron | 1 | 0.004 | 2022016 |

| Araceae | Acorus calamus L | Bojho | Herb | Rhizome | Raw | Common cold, fever, headache, stomach ache | 47 | 0.21 | 2022017 |

| Asclepidaceae | Calotropis gigantea (L.) Dryand | Ank | Shrub | Stem, leaves, flower | Leaves milk eating | Diarrhea, constipation, stomach ache | 1 | 0.004 | 2022018 |

| Asclepidaceae | Marsdenia tinctoria R.Br | Kali lahara | Climber | leaves, flower | Eating | Pneumonia | 1 | 0.004 | 2022019 |

| Aspidiaceae | Dryopteris cochleta (D.Don) C. Chr | Nyuro | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Pneumonia | 12 | 0.054 | 2022020 |

| Aspidiaceae | Dryoathyrium boryanum (Willd.) Ching | Kalo Nyuro | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Pneumonia | 1 | 0.004 | 2022021 |

| Aspidiaceae | Athyrium filix-femina (L.) Roth ex Mert | Unyu | Herb | Leaves | Cooking, eating | Breathing problems, cough, digestive | 2 | 0.009 | 2022022 |

| Asteraceae | Artemisia indica Willd | Titepati | Herb | Whole plant | Juice, powder, paste | Malaria, cutting wound, headache | 202 | 0.902 | 2022023 |

| Asteraceae | Ageratum conyzoides L | Gandhe jhar | Herb | Leaves | Paste using | Infection, allergy | 6 | 0.027 | 2022039 |

| Barberidaceae | Berberis aristata DC | Chutro | Shrub | Leaves | Paste | Eye problem, jaundice | 5 | 0.022 | 2022024 |

| Basellaceae | Basella alba L | Lahare saag | Climber | Leaves, flower | Cooking | Body pain, kidney | 1 | 0.004 | 2022025 |

| Begoniaceae | Begonia picta Sm | Magar kanchi | Herb | Leaves, flower | Paste | Cutting wound, burn | 2 | 0.009 | 2022026 |

| Bombacacea | Bombax ceiba L | Simal | Tree | Bark | Powder paste using | Typhoid, Pneumonia | 3 | 0.013 | 2022027 |

| Brassicaceae | Nasturtium officinale R,Br | Sime jhar | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Immune system | 1 | 0.004 | 2022028 |

| Bromeliaceae | Ananas comosus (L.) Merr | Bhuikatar | Herb | Leaves, fruit | Eating | Vitamin C, immunity | 4 | 0.018 | 2022029 |

| Cannabaceae | Cannabis sativa L | Ganja | Herb | Leaves | Raw, powder, boiling with water | Pain relief, depression, asthma, diarrhoea | 3 | 0.013 | 2022030 |

| Cannabaceae | Carica papaya L | Meva | Shrub | Fruit | Fruit | Skin, cancer, good for body, increased blood | 6 | 0.027 | 2022031 |

| Caryophyllaceae | Drymaria diandra Blume | Abijalo | Herb | Whole plant | Eating | Jaundice, fever | 3 | 0.013 | 2022032 |

| Chenopodiaceae | Chenopodium album L | Bethe saag | Herb | Leaves | Cooking, eating | Digestion, body pain | 14 | 0.063 | 2022033 |

| Chenopodiaceae | Spinacia oleracea L | Palungo | Herb | Leaves | Cooking, eating | Stomach ache, indigestion | 29 | 0.129 | 2022034 |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia chebula Retz | Harro | Tree | Fruit | Boil with water, powder | Fever, tothee | 39 | 0.174 | 2022035 |

| Combretaceae | Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb | Barro | Herb | Fruit | Powder | Infection, cough, fever, liver, sore throat | 35 | 0.156 | 2022036 |

| Compositae | Tagetes erecta L | Sayapatri | Shrub | Flower | Powder with water | Intestinal worms, dysentery, fever, pneumonia | 5 | 0.022 | 2022037 |

| Compositae | Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass | Philinge | herb | Leaves, flower | Eating | Cough | 1 | 0.004 | 2022038 |

| Convolvulaceae | Cuscuta reflexa Roxb | Akasveli | Climber | Whole plant | Paste using juice | Jaundice, body pain, cough | 21 | 0.094 | 2022040 |

| Coriariaceae | Coriaria nepalensis Wall | Machine | Shrub | Leaves | Paste | Fracture | 7 | 0.031 | 2022041 |

| Cruciferae | Brassica juncea (L.) Czern | Rayo saag | Herb | Leaves | Cooking, eating | Body pain | 15 | 0.067 | 2022042 |

| Cruciferae | Raphanus sativus L | Mula | Herb | Root | Eating | Indigestion, gastric | 15 | 0.067 | 2022043 |

| Cruciferae | Lepidium didymium L | Chamsur | Herb | Leaves | CookingEating | Body pain | 27 | 0.121 | 2022044 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucurbita Pipo L | Pharsi | Climber | Fruit | Cooking, eating | Jaundice | 16 | 0.071 | 2022045 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Cucumis sativus L | Kakro | Climber | Fruit | Eating | Jaundice | 9 | 0.04 | 2,022,046 |

| Cucurbitaceae | Momordica charantia L | Titekarela | Climber | Fruit | Eating | Blood pressure | 17 | 0.076 | 2022047 |

| Cupressaceae | Cupressus torulosa D. Don | Dhupi | Shrub | Leaves | Smelling, using paste | Headache | 1 | 0.004 | 2022048 |

| Davalliaceae | Nephrolepis cordifolia (L) Presl | Pani Amala | Herb | Fruit | Eating | Cough, digestion, tonsil | 2 | 0.009 | 2022049 |

| Ericaceae | Lyonia ovalifolia (Wall.) Drude | Angeri pat | Tree | Leaves | Paste | Burning wounds, cutting wounds | 9 | 0.04 | 2022050 |

| Ericaceae | Rhododendron barbatum Wall. ex G. Don | Laligurans | Tree | Flower | Eating, powder with water | Throat problem, dysentry, diarrhea, asthma, constipation | 21 | 0.094 | 2022051 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Phyllanthus emblica L | Amala | Tree | Leaves, fruit | Using paste, eating | Tonsil, vitamin C | 55 | 0.246 | 2022052 |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia hirta L | Dudhe Jhar | Herb | Flower | Eating | Dysentery, jaundice | 1 | 0.004 | 2022053 |

| Fagaceae | Quercus semecarpifolia Sm | Banjh | Tree | Bark | Paste | Fracture | 37 | 0.165 | 2022054 |

| Gentiaanaceae | Swertia chirayita (Roxb.) H.Karst | Chiraito | Herb | Whole plant | Raw, using paste, powder, boiling with water | Fever, typhoid, blood pressure, diarrhea, dysentery, stomach ache | 55 | 0.246 | 2022055 |

| Gramineae | Eleusine coracana (L.)Gaertn | Kodo | Herb | Seed | Cooking with water and drinking | Bones, iron, chickenpox | 5 | 0.022 | 2022056 |

| Gramineae | Saccharum officinarum L | Ukhu | Shrub | Stem | Chewing | Urinary infections, jaundice | 4 | 0.018 | 2022057 |

| Gramineae | Triticum aestivum L | Gahu | Shrub | Leaves | Milky leaves | Blood pressure | 2 | 0.009 | 2022058 |

| Labiatae | Ocimum basilicum L | Tulasi | Herb | Leaves | Eating, powder with water | Coughs, dysentery, diarrhea, fever, common cold | 187 | 0.835 | 2022059 |

| Labiatae | Mentha arvensis L | Pudina | Herb | Whole plant | Paste, powder, boiling with water | Common cold, headache, fever | 67 | 0.299 | 2022060 |

| Labiatae | Mentha piperita L | Babari | Herb | Whole plant | Powder, boil powder with water | Vomiting, common cold, headache | 17 | 0.076 | 2022061 |

| Labiatae | Perilla frutesxens (L.) Britton | Silam | Tree | Seed | Eating | Intestinal worms, vomtiing, common cold, coughs | 17 | 0.076 | 2022062 |

| Labiatae | Pogostemonplectranthoids Desf | Rudilo | Herb | Whole plant | Paste | Allergy, cutting, wound | 197 | 0.879 | 2022097 |

| Lauraceae | Lindera neesiana (Wall. ex Nees) Kurz | Siltimur | Tree | Seed | Boiling with water and drinking | Headache, tooth pain, gastric, diarrhea, stomach ache | 21 | 0.094 | 2022063 |

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum zeylanicum Breyn | Dalchini | Tree | Bark | Eating, boiling with water, and drinking | Diarrhea, gastric, depression, stomach aches, blood pressure, headache | 9 | 0.04 | 2022064 |

| Lauraceae | Litsea monopetala (Roxb. ex Baker) Pers | Kutmiro | Tree | bark, root | Paste | Fracture | 1 | 0.004 | 2022065 |

| Lauraceae | Cinnammomum camphora (L.) J.Presl | Kapur | Tree | Leaves | Eating, juice | Relief pain, common cold, eye problem | 9 | 0.04 | 2022066 |

| Lauraceae | Persea Americana Mill | Avocados | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Blood pressure, skin, coughs, dysentery | 1 | 0.004 | 2022067 |

| Lauraceae | Cinnamomum tamala (Buch.-Ham.) Ness & Eberm | Tejpat | Tree | Leaves | Paste, raw | Fever | 23 | 0.103 | 2022068 |

| Lecythidaceae | Carea arborea Roxb | Kyamuno | Tree | bark | Paste | Cutting wound | 1 | 0.004 | 2022069 |

| Leguminosae | Trigonella foenum-graecum L | Methi | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Fever, constipation, gastric body pain | 30 | 0.134 | 2022070 |

| Leguminosae | Calopogonium mucumoides Desv | Gahate Jhar | Herb | Leaves | Paste using | Stomach ache, bacterial infection, diarrhea | 1 | 0.004 | 2022071 |

| Leguminosae | Bauhinia variegata L | Koiralo | Herb | Flower | Soup drinking | Diarrhea, stomach ache | 2 | 0.009 | 2022072 |

| Leguminosae | Butea minor Buch.-Ham.ex Baker | Bhuletro | Shrub | Flower | Eating | Headache | 1 | 0.004 | 2022073 |

| Leguminosae | Dolochos lablab L | Simi | Climber | Leaves | Eating | Skin allergy | 12 | 0.054 | 2022074 |

| Leguminosae | Acacia catechu (L.f) Willd | Khayar | Tree | Leaves | Eating | Diarrhea, body pain | 2 | 0.009 | 2022075 |

| Leguminosae/Febaceae | Mimosa pudica L | Buhari Jhar | Herb | Leaves, root | Eating | Fever, urinary infections | 4 | 0.018 | 2022076 |

| Liliaceae | Asparagus racemosus Wall | kurilo | Herb | Stem | Eating | Pain, swelling, vitamin, milk problem in women | 36 | 0.161 | 2022077 |

| Liliaceae | Allium hyposistum Stearn | Jimbo | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Common cold, fever, body pain | 7 | 0.031 | 2022078 |

| Liliaceae | Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f | Ghuikumari | Herb | Whole plant | Leaf | Burning wound, good for skin, hair, allergy, diabetes, diarrhea | 37 | 0.165 | 2022079 |

| Liliaceae | Paris polyphylla Sm | Satuwa | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Snake bites | 1 | 0.004 | 2022080 |

| Loranthaceae | Viscum articulatum Burm.f | Hadchur | Tree | Leaves | Paste | Fracture, body pain | 3 | 0.013 | 2022081 |

| Lythraceae | Woodfordia fruticosa (L.) Kurz | Dhayero | Tree | Flower | Eating | Dysentery, diarrhea | 7 | 0.031 | 2022082 |

| Malvaceae | Sida cordifolia L | Balu jhar | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Common cold, urinary infection, intestinal worms, coughs | 3 | 0.013 | 2022083 |

| Meliaceae | Azadirachta indica A. Juss | Nim | Tree | Leaves, bark | Boiling with water and drinking | Intestinal worms, blood pressure, fever, common cold | 43 | 0.192 | 2022084 |

| Meliaceae | Melia azederach L | Bakaino | Tree | Leaves, bark | Eating | Intestinal worms | 28 | 0.125 | 2022085 |

| Menispermaceae | Tinospora cordifolia (Willd.)Miers | Gurjo | Climber | Stem | Dried, boiling with water | Dysentery, fever, common cold, fever, digestion, stomach ache, pressure, skin disease, diarrhea | 168 | 0.75 | 2022087 |

| Menispermaceae | Stephania japonica (Thunb.) Miers | Batule Paat | Climber | Leaves | Eating | Mensuration, heavy bleeding | 1 | 0.004 | 2022088 |

| Moraceae | Artocarpus integr (Thunb.) Merr | Rukh Kathar | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Immune system/weakness | 5 | 0.022 | 2022089 |

| Moraceae | Ficus lacor Buch-Ham | Kabhro | Tree | Leaves | Juice, paste eating | Gastric, fever | 9 | 0.04 | 2022090 |

| Moraceae | Ficus religiosa L | Pipal | Tree | Leaves | Raw | Headache | 9 | 0.04 | 2022091 |

| Musaceae | Musa paradisiaca L | Kera | tree | Fruit | Eating | Constipation | 8 | 0.036 | 2022092 |

| Myrtaceae | Syzigium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & Perry | Lwang | Tree | Flower | Raw | Immune system, asthma, pain, tooth problem | 47 | 0.21 | 2022093 |

| Myrtaceae | Psidium guajava L | Amba | Tree | Bark, leaves, fruit, flower | Powder boiling with water, paste | Cough, dysentery, pain relief, diabetes, diarrhoea, intestinal worm | 60 | 0.268 | 2022094 |

| Myricaceae | Myrica esculenta Buch.-Ham.ex D. Don | Kaphal | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Diarrhea, fever, throat disorder | 7 | 0.031 | 2022095 |

| Myristiccaeae | Myristica fragrans Houtt | Jayaphal | Tree | Seed, fruit | Eating | Stomach ache, indigestion, common cold, fever | 21 | 0.094 | 2022096 |

| Oleaceae | Nyctanthes arbor-tristis L | Parijaat | Tree | Leaves | Paste | Fever, touncil | 23 | 0.103 | 2022098 |

| Oleaceae | Jasminum humile L | Jai | Shrub | Leaves, flower | Juice, paste eating | Tonsil, mouth infection | 35 | 0.156 | 2022099 |

| Orchidaceae | Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D. Don) So | Panc aule | Herb | Tube, root | Powder, paste | Indigestion, tooth problem | 15 | 0.067 | 2022100 |

| Oxalidaceae | Oxalis acetosella L | Chariamilo | Herb | Leaves | Paste | Diarrhea, snake bites, fever, stomach ache | 28 | 0.125 | 2022101 |

| Pedaliaceae | Sesamum indicum L | Til | Herb | Seed | Raw, paste, Juice | Hair, skin, allergy | 7 | 0.031 | 2022102 |

| Phyllanthaceae | Phyllanthus parvifolius Buch.-Ham. ex D. Don | Paineti | Shrub | Leaves stem | Juice | Menstrual, stomach ache | 0.004 | 2022103 | |

| Pinaceae | Pinus roxburghii Sarg | Khote Salla | Tree | Bark | Bark gum | Digestive, liver | 3 | 0.013 | 2022104 |

| Piperaceae | Piper nigrum L | Marich | Climber | Flower | Boil with water | Menstrual pain, diarrhea, depression, cancer, stomach | 50 | 0.223 | 2022105 |

| Pittosporaceae | Pittosporum napaulense (DC.) Rehder et Wilson | Khorsnai | Tree | Bark | Paste | Injured, pain, fracture | 24 | 0.107 | 2022106 |

| Poaceae | Cynodon dactylon (L.) Pers | Dubo | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Dysentery, diarrhea, headache | 1 | 0.004 | 2022107 |

| Poaceae | Imperata cylindrica (L.) P.Beauv | Siruphool | Herb | Leaves, flower | Juice, paste | Indigestion, diarrhoea, cutting wound | 1 | 0.004 | 2022108 |

| Polygonaceae | Fagopyrum esculentum Moench | Phapar | Herb | Seed, leaves | Eating | Body pain | 3 | 0.013 | 2022109 |

| Polygonaceae | Rheum webbianum Royle | Padamchal | Herb | Flower, leaf | Eating, using paste powder | Stomach ache, body pain, cutting, wound | 4 | 0.018 | 2022110 |

| Punicaceae | Punica granatm L | Anar | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Skin, unrine infection, digestive, wound | 3 | 0.013 | 2022111 |

| Rosaceae | Prunus persica (L.) Batsch | Aaru | Tree | Leaves, seed, fruit | Eating | Menstrual, digestion, h eal wound | 4 | 0.018 | 2022112 |

| Rosaceae | Rubus ellipticus Sm | Ainselu | Shrub | Leaves, root, fruit | Eating | Fever, cough, tonsil, pneumonia, chest pain | 21 | 0.094 | 2022113 |

| Rosaceae | Rosa alba L | Gulaph | Herb | Flower | Eating | Diarrhea, headache | 5 | 0.022 | 2022114 |

| Rosaceae | Pyrus communis L | Naspati | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Diabetes | 1 | 0.004 | 2022115 |

| Rosaceae | Prunus cerasoides D.Don | Painyu | Tree | Leaves | Eating paste | Fever, burning wound | 3 | 0.013 | 2022116 |

| Rubiaceae | Rubia manjith Roxb.ex fleming | Majitho | Herb | Leaves | Eating paste | Blood pressure, urine infection | 7 | 0.031 | 2022117 |

| Rubiaceae | Adina cordifolia (Roxb.) Brandis | karam | Tree | Leaf, bark | Eating | Stomach ache, fever, jaundice | 1 | 0.004 | 2022118 |

| Rutaceae | Aegle mammelos (L.) Corr | Bel | Tree | Leaves, bark, fruit, seed | Eating | Dysentery | 1 | 0.004 | 2022119 |

| Rutaceae | Citrus x limon (L.) Osbek | Nibuwa | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Sore throat, pressure, blood increase | 15 | 0.067 | 2022120 |

| Rutaceae | Citrus Sinensis (L.) Osbeck. Var. jungar | Junar | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Pain relief, headache, depression, indigestion | 7 | 0.031 | 2022122 |

| Rutaceae | Citrus aurantifokia (Christ).Swingle | Kagati | Shrub | Fruit | Raw, juice, boil with water | Common cold, relief, decrease fat, skin disease | 46 | 0.205 | 2022123 |

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum acanthopodium DC | Timur | Tree | Seed | Eating | Snake bites, stomach ache | 25 | 0.112 | 2022124 |

| Sapotaceae | Madhuca longifolia (Koenig) Mac | Mahuva | Tree | Flower | Powder, paste | Skin disease | 1 | 0.004 | 2022125 |

| Saxifragaceae | Bergenia ciliata (Haw.)Sternb | Pakhan bhed | Herb | Rhizome, leaf, flower | Eating | Menstrual, stomach ache, uterus | 27 | 0.121 | 2022126 |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum frutescens L. var. cerasiforme Bailey | Jyanmara khursani | Herb | Fruit | Eating | Gastric | 34 | 0.152 | 2022127 |

| Solanaceae | Capsicum annuum L | Khursani | Herb | Fruit | Eating | Indigestion, gastric | 30 | 0.134 | 2022128 |

| Solanaceae | Datura stramonium L | Dhaturo | Herb | Leaves | Eating | Intestinal worms, indigestion | 2 | 0.009 | 2022129 |

| Solanaceae | Solanum surattense Burm.f | Kanyakumari | Herb | Leaves | Eating, paste | Fever, diabetes, asthma, urine infection, tooth problem | 1 | 0.004 | 2022130 |

| Solanaceae | Capsium frutescens L. var. grossum Bailey | Vede Khorsani | Shrub | Fruit | Cooking | Gastric | 1 | 0.004 | 2022131 |

| Solanaceae | Lycopersicum esculentum Mill | Tamatar | Shrub | Fruit | Eating | Burning wound | 5 | 0.022 | 2022132 |

| Solanaceae | Solanum erianthum D.Don | Dhursul pati | Tree | Leaves | Eating, paste | Headache, cough | 17 | 0.076 | 2022133 |

| Theaceae | Schima Wallichii (DC.) Korth | Cilaune | Tree | Leaves, bark, stem | Paste | Cutting wound | 3 | 0.013 | 2022134 |

| Umbelliferae | Daucas carota L. var. satva DC | Gajar | Herb | Root | Eating | Intestinal worms, dysentery | 2 | 0.009 | 2022135 |

| Umbelliferae | Carum carvi L | Kalo jira | Herb | Seed | Raw | Fever, headache | 5 | 0.022 | 2022136 |

| Umbelliferae | Coriandrum sativum L | Dhaniya | Herb | Seed, leaves | Boil with water, powder | Headache, common cold | 15 | 0.067 | 2022137 |

| Umbelliferae | Foeniculum vulgare Mill | Madeshi Souf | Herb | Root, seed | Raw, boil with water, powder | Digestive, reproductive, body pain | 57 | 0.254 | 2022138 |

| Umbelliferae | Trachyspermum ammi (L.) Sprague | Jvano | Herb | Seed | Dry powder, boil with water | Diarrhea, stomach ache, common cold, fever, pain, immunity | 56 | 0.25 | 2022139 |

| Urticaceae | Urtica dioica L | Signup | Shrub | Leaves | Eating | High pressure, body pain, gastric, vitamin A jaundice | 40 | 0.179 | 2022140 |

| Valerianaceae | Valeriana jatamansii Jones | Sughandawal | Herb | Whole plant | Smelling, using paste | Depression, Headache | 1 | 0.004 | 2022141 |

| Verbenaceae | Premna integrifolia L | Gidari | Shrub | Bark, root, stem, leaves | Juice | Typhoid, stomach ache | 12 | 0.054 | 2022142 |

| Verbenaceae | Callicarpa macrophylla Vahl | Guyallo | Shrub | Eating | Fruit, flower | Pneumonia | 5 | 0.022 | 2022143 |

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale Rosc | Aduwa | Herb | Rhizome | Powder, pate, juice, boil with water | Diarrhea, dysentry, nausea, tonsil, common cold, gastric | 203 | 0.906 | 2022144 |

| Zingiberaceae | Curcuma angustifolia Rpxb | Besar/Haledo | Herb | Rhizome | Raw, boiling with water, powder with water | Diarrhea, dysentery, cutting wound, allergy, tonsil, fever, common cold, digestion | 214 | 0.955 | 2022145 |

| Zingiberaceae | Kaempferia rotunda L | Bhuin champa | Herb | Flower | Eating | Cancer, Swellings, Cuts, | 1 | 0.004 | 2022146 |

| Zingiberaceae | Costus speciosus (Koenig.) Sm | Betlauri | Shrub | Flower, bud, leaf | Eating | Fever, intestinal worm, urine infection | 2 | 0.009 | 2022147 |

| Zingiberaceae | Amomum subulatum Roxb | Alainchi | Tree | Fruit | Boil with water, milk, powder | Diarrhea, vomiting cough | 45 | 0.201 | 2022148 |

| Zingiberaceae | Curcuma caesia Roxb | Kalohaledo | Herb | Rhizome | Paste, boil with water, powder | Pneumonia, stomach ache, common cold, fever, headache | 25 | 0.112 | 2022149 |

| Zingiberaceae | Elettaria cardamomum Maton | Sukhmel | Tree | Fruit | Eating | Oral disease, asthma, diarrhea, kidney disorder | 34 | 0.152 | 2022150 |

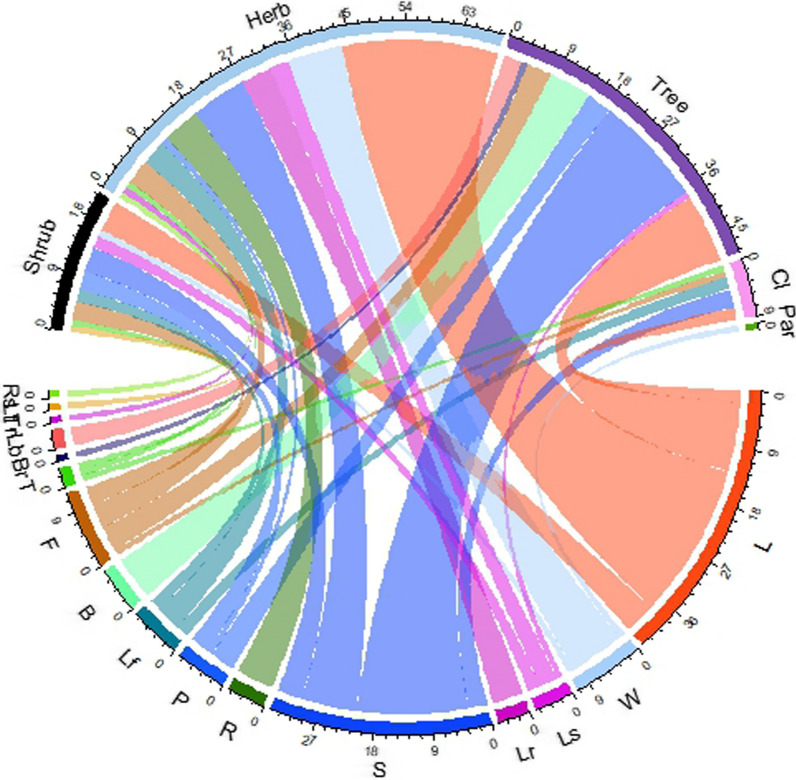

Habit with the plant parts used in medicine

Most recorded species, 69 (46.3%), were herbs, followed by trees, 48 (32.21%), shrubs, 22 (14.77%), climbers, 9 (6.04%), and parasites, 1 (0.67%). Nearly all plant parts were used in ethnomedicine. However, the most frequently used plant parts were leaves in 74 (49.67%) of the species, followed by fruit 30 (20.13%), flower 19 (12.75%), seed 11 (7.38%), whole plant 11 (7.38%), bark 11 (7.38%), root 7 (4.69%), stem 6 (4.02%), rhizome 5 (3.35%), and bulb 4 (2.68%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Habit-wise parts of the plant used to treat diseases (where Rs = root/rhizome/bulb, seed/fruit, Lt = leaves, trunk, Lb = Leaves, bark, Br = bark, root/rhizome/bulb, T = stem, F = flower, B = bark, Lf = leaves and flower, P = bark, root, stem, leaves/leaves, bark, stem/root, leaves, flower/leaves, root, stem/bark, leaves, stem, fruits/stem, leaves, fruits, R = root/rhizome/bulb, S = fruits/seed, Lr = leaves, root, Ls = leaves, seed/fruit, W = whole plants, L = leaves, Par = parasites, Cli = climber)

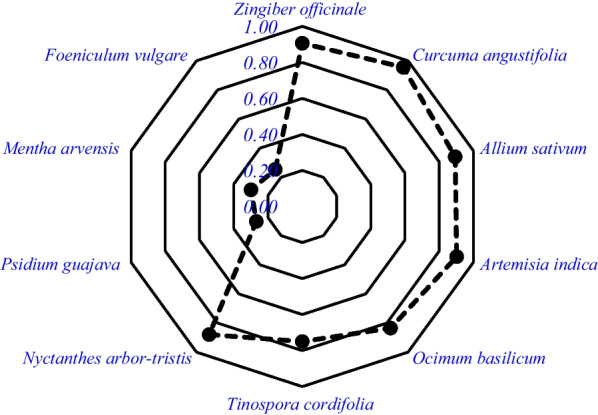

Relative frequency of citation (RFC)

The relative frequency of medicinal plant citations ranged from 0.004 to 0.955, with Curcuma angustifolia (0.9554) having the highest frequency, followed by Zingiber officinale. (0.9063), Artemesia indica (0.902), Allium sativum (0.893) and Nyctanthes arbor-tristis (0.879) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Top ten ranked plant species reported by respondent where there are ten radar lines one radar represent 0.1 and goes up to 1. The black solid point is the RFC value of the species

List of plants with diseases treated

The recorded 149 medicinal plants were used to treat 48 disorders and 13 disease categories. The greatest number of medicinal plants (119) was employed to treat digestive disorders (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of plant species used for specific categories of disease and ailments

| Ailments categories | Local terms/emic use reports (biomedical term) | Number of species |

|---|---|---|

| Circulatory | Rakta chap badeko (blood pressure) | 17 |

| Mirgaula ramro banauxa (help Kidney function) | ||

| Kalejo ramro banauxa (help liver function) | ||

| Digestive | Kabjiyet/ disa garna garo huda (constipation) | 119 |

| Pakhala/Cherpati Lageko (diarrhea) | ||

| Aaun parda (dysentery) | ||

| Aapach/Khana naruchda (indigestion) | ||

| Pet ma Juka parda (intestinal worms) | ||

| Pahelo rog (jaundice) | ||

| Pet dukhda (stomachache) | ||

| Banta/ulti huda (nausea, vomiting) | ||

| Amilo pani aune/Chati dukhda (Gastritis) | ||

| Endocrine | Chini rog/Sugar (diabetes) | 7 |

| Eye | Aankha ka samasyaharu huda (eye complaints) | 3 |

| Aankha pakda (eye allergy) | ||

| General and unspecified | Jooro (fever) | 37 |

| Machet/ kira le tokda (malaria) | ||

| Jwaro, banta, tauko dukhda, diarrhea (typhoid) | ||

| Sarpa le tokda (snakebite) | ||

| Genetic disorder | Gatha, Girkho, chala palauda (cancer) | 3 |

| Mental illness | Tanab/Dhapedi huda/ Jharko lagda (depression) | 5 |

| Musculoskeletal | Jiu dukheko (bodyache) | 46 |

| Haddi kamjori (bone weakness) | ||

| Haddi vachiyeko/Futeko (fracture) | ||

| Kamjor huda (weakness) | ||

| Haad/Jorni dukhda (arthritis) | ||

| Jyan Dukhda kheri (body pain) | ||

| Dant/Gija Dukhda (toothache) | ||

| Neurological | Tauko dukhda (headache) | 15 |

| Post-partum hemorrhage | Dherai ragat bagda (menstrual bleeding) | 7 |

| Pathe ghar dukhda (uteral disorder) | ||

| Respiratory | Dam/Sas ferna garo huda (asthma) | 66 |

| Ruga/Khoki (common cold) | ||

| Khasi (cough cold) | ||

| Naak bata ragat bagda (nose bleeding) | ||

| Fokso ko samsya huda (pneumonia) | ||

| Fokso/chati dukhda (tuberculosis) | ||

| Ghanti Basda/dhukda (sore throat, tonsillitis) | ||

| Skin | Luto auda (scabies) | 45 |

| Poleko/dadeko (burn, scalds) | ||

| Kateko (cuts and injuries) | ||

| Kapal jharda (hair fall) | ||

| Sarir ma daag auda (skin infection) | ||

| Chala rog (skin fungal diseases) | ||

| Urinary system | Pisab Polda/ragat dekhida (Hematuria, uric acid problem) | 10 |

| Pisab pahelo (urine infections) |

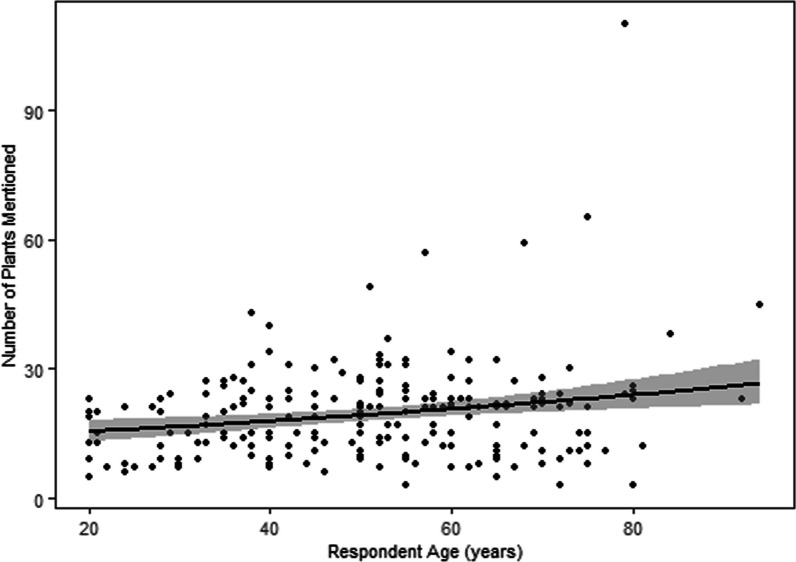

The use of medicinal plants varies with the sociocultural variables

Age and occupation were the only variables among age, gender, education, occupation, ethnicity, and religion significantly associated with the number of plants reported (Table 4). Figure 4 demonstrates that older individuals mentioned more medicinal plants (p = 0.0001) than younger individuals. People in the agri-business sector reported significantly (p = 0.003) more medicinal plants than those in other occupations.

Table 4.

Summary table of the generalized linear model (GLM) with quasi-Poisson showing knowledge about the number of medicinal plants among the respondents where sign * indicates significance

| Variables | Estimate | Std.Error | t-value | p-value | Lo.CI | Up.CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 8.716 | 2.714 | 3.212 | 0.002 | 3.397 | 14.035 |

| Age (years) | 0.191 | 0.048 | 3.956 | 0.0001* | 0.096 | 0.286 |

| Occupation_agri-business | 8.607 | 2.908 | 2.959 | 0.003* | 2.906 | 14.308 |

| Occupation_Service | 2.956 | 2.174 | 1.36 | 0.175 | − 1.305 | 7.218 |

Fig. 4.

Number of plants reported with the age of the respondents

Status of medicinal plants and their traditional knowledge

The major challenges and threats in ethnomedicine were the migration of young people to urban areas, land use change in the village, and a decreasing use of forest products. Respondents reported a decrease in the population of some plants (21) as a threat to conservation caused by untrained and unprofessional collection. The sharing of ethnomedicinal knowledge was believed to decrease the effectiveness of medicine; therefore, all the traditional healers (Dhami and Jhakri) and three Vaidhya (Ayurvedic physicians) were not effortlessly passing their knowledge to the younger generation. Further, the hegemony of allopathic medicine is cited as a concern for limiting ethnomedicine. From observation, it was found that in the entire surveyed area, only one botanical to distribute medicinal plants and products; however, there were four health centers to sell allopathic medicine. Similarly, youth were found to have a diminished interest in ethnomedicine. For instance, we recorded an average of 20 species per respondent, with 20- to 29-year-olds reporting an average of 14 plant species.

Changes in land use patterns also represent a significant obstacle for using ethnomedicinal plants. Two (1.34%) of the 149 species recorded were purchased from a market, while the remaining 147 (98.65%) were collected from agricultural land, 76 (51%), forest, 49 (32.89%) and fallow/transition land, 22 (14.77%). The land use change analysis revealed a 56.67% decrease in shrubland area and a 32.05% decrease in agricultural land area (Table 5), limiting the availability of medicinal plants. Change in land use also prevailed the dissented medicinal plants picking sites and traditional harvesting calendars.

Table 5.

Summary of LULC change in the period 1999–2020 in hectares

| LULC/Year | 1999 | 2010 | 2020 | Overall change in 21 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest area | 45 (35.46%) | 57.6 (45.39%) | 70.2 (55.32%) | + 56% (1.2 ha−1) |

| Water bodies | 8.1 (6.38%) | 4.86 (3.83%) | 5.76 (4.54%) | − 28.88% (0.11 ha−1) |

| Barren land | 5.4 (4.26%) | 4.95 (3.90%) | 7.2 (5.67%) | + 3.33% (0.08 ha−1) |

| Settlement area | 4.5 (3.55%) | 8.1 (6.38%) | 12.6 (9.93%) | + 180% (0.38 ha−1)) |

| Agriculture land | 14.04 (11.06%) | 15.39 (12.13%) | 9.54 (7.52%) | − 32.05% (0.21 ha−1) |

| Shrub land | 49.86 (39.29%) | 36 (28.37%) | 21.6 (17.02%) | − 56.67% (1.34 ha−1) |

Discussion

We recorded more ethnomedicinal plants than previous studies from eastern Nepal [27, 30–32]. In indigenous community-centered studies, [30] focused on the Lepcha community of Illam district, eastern Nepal, and recorded 35 species, while the Rai community-focused study in the Bhojpur district, eastern Nepal, recorded 35 species [32]. A study from Kavrepalanchok District, central Nepal, recorded 116 species [33]. A study from the Machhapuchchhre rural municipality of Kaski District, Nepal, recorded 105 species [23]. A study from far west Nepal recorded 135 species [34]. A study conducted in villages of central and western Nepal reported 192 medicinal plants [35]. This indicates that the Champadevi area is rich in medicinal plant knowledge, similar to other parts of Nepal, which might be related to the geographical uniqueness and remote area inhabiting indigenous people lacking medical resources [36].

Our research demonstrated a similarity index of 0.077 to Bhattarai and Khadka [26], 0.054 to Bhattarai [27], and 0.050 to Shrestha et al. [28]. Least similarity indices (0.07–0.05) indicate that more unique species have been recorded in Okhaldhunga district, revealing that people rely more on locally available medicinal plants to treat illness.

The differences in the use of species may be attributable to the people's socioeconomic status, including a link to national roads and health facilities, as well as awareness [23] and easy access. The differences in the use of species may be bonded to the people's socioeconomic status, including a link to national roads and health facilities, as well as awareness. It is evident that the people of remote and hilly, Nepal, have extensive knowledge of medicinal plants [10].

Plant parts used and their growth forms

Among the choices of plant parts, leaves, fruits, and flowers were most frequently collected and utilized. Due to their more frequent collection than roots and bark, leaves were also harvested and processed to create various mixtures. The leaves of a plant are the most sensitive because they contain the highest concentrations of bioactive secondary metabolites and play an essential role in the plant's defense system [37]. Additionally, the preparation of leaf extracts preserves the drug's active components more effectively than other plant parts [38]. In contrary, root contains more bio active compounds [39].

Herbs constituted the majority of collected and utilized species (46%), followed by trees (32.67%). As tree leaves and herbs were frequently valued and apparent trees and abundant herbs were primarily selected, ecological traits were followed in the selection of medicinal plants. However, the random selection was prevalent on other parts of the country [40, 41]. Irrespective to our hypothesis, plant collection was influenced more by the ecological traits (abundance and apparency). As herbs are simple to cultivate and abundant, they are easy to harvest, process, and prepare for pharmacological consumption [42]. It is believed that the medicinal benefits of a plant increase with its abundance [43]. Moreover, obvious or salient plants are frequently collected [8]. In addition, secondary metabolites are more abundant in herbs [44].

Medicinal plants use and sociocultural variables

Our hypothesis tested yielded significant relationship with the age and occupation group among the socioeconomic variables age, gender, education, occupation, ethnicity, and religion. Older respondents reported more plants than younger ones. It may be due to the elders' increased plant knowledge. Nonetheless, this may be more than a mere factor, as plant knowledge is linked to social context [45]. Older generations serve as custodians of traditional knowledge, are more familiar with traditional treatments, and have limited exposure to modern medical procedures [46]. It may also be attributable to the younger generation's disinterest in traditional medicine and related to the time they spend with their elders. Young people are highly mobile in pursuing opportunities [47]. Agri-businessmen reported more medicinal plants than other respondents (service men). These businessmen are locally engaged in the medicinal plant industry, local medicinal plant expert products, and food-related businesses, which may have aided them in acquiring a deeper understanding of medicinal plants. It is evident that people engaged in the medicinal plant business have more medicinal knowledge [48]. As medicinal plant use is more dependent on family background and the transfer of plant knowledge is dependent on family, business people may have had an excellent opportunity to converse about plants at home [49].

Conservation of medicinal plants and their traditional knowledge

Due to rapid population growth, poverty, a lack of valuation of ecological services, and ignorance of biophysical limitations, the area of lower vegetation (herbs and shrubs) and anthropogenic landscape have decreased due to human activities, including settlement and built-up areas. This change has altered the region's physical landscapes and ecosystem services [50]. Population of 21 species (Drymaria diandra, Curcuma caesia, Basella alba, Achyranthes bidenata, Bombax ceiba, Cuscuta reflexa, Bergenia ciliata, Carea arborea, Swertia chirayita, Butea minor, Viscum articulatum, Woodfordia fruticosa, Adina cordifolia, Premna integrifolia, Rheum webbianum, Mangifera indica, Terminalia chebula, Terminalia bellirica, Callicarpa macrophylla, Melia azederach, and Marsdenia tinctoria were reported to have declined due to land use change followed by a change in agricultural area. Evidently, land use change alters plant use patterns and promotes more use of resources from the secondary forest and the use of non-indigenous species [7].

For ethnomedicine, the sociocultural transformation may be one of the significant threats and challenges [51], which includes the migration of youth to urban areas in search of good opportunities [32] and the disinterest of young people in traditional medical practices, similar to other global records [52]. Typically, older people are the source of ethnomedicine, but sometimes, they pass away without passing on their knowledge to the younger generation, which poses a significant threat to ethnomedicine [53]. A study from Nepal revealed that youths are less interested in ethnomedicine [21], which is another threat to ethnomedicine. However, rural people prefer to retain their knowledge of medicinal plants [54]. There is a belief that sharing ethnomedicinal plant use knowledge diminishes healing effectiveness, so most local healers in Nepal wish to keep their ethnomedicinal knowledge secret. However, most of them impart their knowledge to close relatives, such as sons, daughters, and daughters-in-law.

The dominance of allopathic medicine is also a challenge for ethnomedicine, given that allopathic medicine is readily available and believed to have a rapid healing capacity [55]. Traditional healers should impart traditional knowledge to the younger generation to preserve this knowledge. The valuable knowledge of ethnomedicine should be preserved, and young people should be made aware of the ethnomedicinal system. A mechanism for intergenerational learning should be established [56] by organizing interaction programs for younger and older villagers and households.

Conclusions

We recorded 149 medicinal plants from 68 families and 130 genera used to treat 48 diseases. The most plants were used for digestion (119), while the fewest were used for genetic disorders (3). C. angustifolia was the most frequently cited medicinal species, followed by Z. officinale, A. sativum, A. indica, and O. basilicum. Our study supported the positive relationship of medicinal plant use knowledge with the elder people and people involve in agri-business. Changes in land use, population decline, and unsustainable medicinal plant harvesting practices posed the greatest threats to medicinal plant conservation in Okhaldhunga. The major threats to medicinal plants and their knowledge are sociocultural transformation, vertical transfer of plant knowledge, and youth disinterest. We suggest managing ongoing land use change and human migration and educating individuals on the traditional medical system.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the respondents who participated in this survey. We also like to thank local healer Ganga Prasad Kattel for helping in collection and identification of local plants in the field.

Abbreviations

- CBS

Central Bureau of Statistics

- FC

Frequency of citation

- FGDs

Focus group discussions

- GIS

Geographic Information System

- GLM

Generalized linear model

- ICPC

International classification of primary care

- KATH

National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories

- LRMP

Land and resource management

- MLC

Maximum likelihood classifier

- RFC

Relative frequency of citation

- RSI

Rahman's similarity Index

- USGS

US Geological Survey's

Author contributions

Deepa Karki (DK), Dipak Khadka (1DK), SB, PCA and RMK contributed to conceptualization; DK, 1DK, RMK contributed to methodology, formal analysis, data curation and writing—original draft preparation; DK, 1DK and PCA contributed to software; 1DK, RMK, PCA contributed to validation; DK contributed to investigation; DK, 1DK, SB, SS contributed to resources; HRP, DK, RMK contribtuted to plant identification and verification; RMK, 1DK; PCA; HRP, SS contributed to writing—review and editing; RMK, PCA, 1DK, HRP, SS contributed to visualization; 1DK, SB, HRP, RMK, PCA, SS contributed to supervision; and 1DK and SS contributed to project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou, Grant No. 202102021016.

Availability of data and materials

All the data used in this study are used in the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research has followed Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics guidelines (ISE 2008). Oral consent was acquired from the respondents before conducting interviews. No ethical committee permits were required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ripu Mardhan Kunwar, Email: ripukunwar@gmail.com.

Shi Shi, Email: shis@scau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ghimire SK. Medicinal plants in the Nepal Himalaya: current issues, sustainable harvesting, knowledge gaps and research priorities. Med Plants Nepal Anthol Contemp Res. 2008;25–42.

- 2.Rokaya MB, Münzbergová Z, Shrestha MR, Timsina B. Distribution patterns of medicinal plants along an elevational gradient in central Himalaya. Nepal Journal of Mountain Science. 2012;9:201–213. doi: 10.1007/s11629-012-2144-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurung K, Pyakurel D. Identification manual of commercial medicinal and aromatic plants of Nepal. Kathmandu: Nepal Herbs and Herbal Products Association (NEHHPA); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunwar R, Sher H, Bussmann R. Ethnobotany of the Himalayas. 1. Cham: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magar RA, Mallik AR, Chaudhary S, Parajuli S. Ethno-medicinal plants used by the people of Dharan, Eastern Nepal. CSIR-NIScPR. 2022;12(1):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maharjan R, Thapa R, Nagarkoti S, Sapkota P. Ethnobotanical uses of home garden species around Lalitpur district, Nepal. Asian J Pharmacogn. 2021;4(2):10–22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunwar RM, Baral K, Paudel P, Acharya RP, Thapa-Magar KB, Cameron M, Bussmann RW. Land-use and socioeconomic change, medicinal plant selection and biodiversity resilience in far Western Nepal. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kutal D, Kunwar RM, Baral K, Sapkota P, Sharma HP, Rimal B. Factors that influence the plant use knowledge in the middle mountains of Nepal. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi N, Ghorbani A, Siwakoti M, Kehlenbeck K. Utilization pattern and indigenous knowledge of wild medicinal plants among three ethnic groups in Makawanpur district, Central Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;262:113219. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kunwar RM, Baral B, Luintel S, Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Adhikari B, Adhikari YP, Subedi SC, Subedi CK, Poudel P, Paudel HR. Ethnomedicinal landscape: distribution of used medicinal plant species in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022;18(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13002-022-00531-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford JD, King N, Galappaththi EK, Pearce T, McDowell G, Harper SL. The resilience of indigenous peoples to environmental change. One Earth. 2020;2(6):532–543. doi: 10.1016/j.oneear.2020.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar M, Radha Devi H, Prakash S, Rathore S, Thakur M, Puri S, Pundir A, Bangar SP, Changan S, Ilakiya T. Ethnomedicinal plants used in the health care system: survey of the mid hills of Solan district, Himachal Pradesh, India. Plants. 2021;10(9):1842. doi: 10.3390/plants10091842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brian C, Shah PB, Maharjan PL. Land resource mapping project (LRMP). Land system report: the soil landscapes of Nepal. Kenting Earth Sciences Limited; 1986.

- 14.Henriksen MW, Lund MH. Factors influencing delay and compliance to treatment among the patients in Okhaldhunga, Nepal. Master's thesis; 2006.

- 15.Gyawali I, Bhattarai S, Khanal S. Ethnobotanical, photochemical, and allelopathic potentinal of traditional medicinal plants. Turk J Agric Food Sci Technol. 2021;9(1):224–233. [Google Scholar]

- 16.CBS. National population and housing census 2021. Caste/Ethnicity; 2021.

- 17.International Society of Ethnobiology. International society of ethnobiology code of ethics (with 2008 additions) (2006). http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/

- 18.Jain D, Chattopadhyay D. Analysis of gene expression in response to water deficit of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) varieties differing in drought tolerance. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lillesand T, Kiefer RW, Chipman J. Remote sensing and image interpretation. Hoboken: Wiley; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu D, Mausel P, Batistella M, Moran E. Comparison of land-cover classification methods in the Brazilian Amazon Basin. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens. 2004;70(6):723–731. doi: 10.14358/PERS.70.6.723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojha SN, Tiwari D, Anand A, Sundriyal RC. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of a marginal hill community of Central Himalaya: diversity, usage pattern, and conservation concerns. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16(1):1–21. doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain) Econ Bot. 2008;62:24–39. doi: 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adhikari M, Thapa R, Kunwar RM, Devkota HP, Poudel P. Ethnomedicinal uses of plant resources in the Machhapuchchhre rural municipality of Kaski District, Nepal. Medicines. 2019;6(2):69. doi: 10.3390/medicines6020069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorensen TA. A method of establishing groups of equal amplitude in plant sociology based on similarity of species content, and its application to analyses of the vegetation on Danish commons. Biol Skr. 1948;5:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman IU, Hart R, Afzal A, Iqbal Z, Ijaz F, Abd-Allah EF, Ali N, Khan SM, Alqarawi AA, Alsubeie MS, Bussmann RW. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2019;17(2):2765–2777. doi: 10.15666/aeer/1702_27652777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhattarai KR, Khadka MK. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants from Ilam District, East Nepal. Our Nat. 2016;14(1):78–91. doi: 10.3126/on.v14i1.16444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhattarai KR. Ethnobotanical survey on plants used in Mai Municipality of Ilam district, eastern Nepal. Banko Janakari. 2020;30(2):11–35. doi: 10.3126/banko.v30i2.33476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shrestha N, Shrestha S, Koju L, Shrestha KK, Wang Z. Medicinal plant diversity and traditional healing practices in eastern Nepal. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;192:292–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core T. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2016.

- 30.Bhattarai KP. Ethnomedicinal plants of Lepcha community in Ilam district, eastern Nepal. Nepal J Biosci. 2013;3(1):64–68. doi: 10.3126/njbs.v3i1.41448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rai MB. Medicinal plants of Tehrathum district, eastern Nepal. Our Nat. 2003;1(1):42–48. doi: 10.3126/on.v1i1.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paudyal SP, Rai A, Das BD, Paudel N. Ethnomedicinal knowledge on Rai community of Ramprasadrai rural municipality, Bhojpur district, eastern Nepal. Eur J Biol Res. 2021;11(3):367–380. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ambu G, Chaudhary RP, Mariotti M, Cornara L. Traditional uses of medicinal plants by ethnic people in the Kavrepalanchok district, central Nepal. Plants. 2020;9(6):759. doi: 10.3390/plants9060759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunwar RM, Uprety Y, Burlakoti C, Chowdhary CL, Bussmann RW. Indigenous use and ethnopharmacology of medicinal plants in far-west Nepal. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2009;7:005–028. doi: 10.17348/era.7.0.5-28. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunwar RM, Lamichhane-Pandey M, Mahat-Kunwar L, Bhandari A. Medicinal plants and ethnomedicine in peril: a case study from Nepal himalaya. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Huang SS, Huang CH, Ko CY, Chen TY, Cheng YC, Chao J. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Kinmen. Front Pharmacol. 2022; 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Bhattarai S, Chaudhary RP, Taylor RS. Ethno-medicinal plants used by the people of Nawalparasi district. Cent Nepal Our Nat. 2009;7(1):82–99. doi: 10.3126/on.v7i1.2555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okello SV, Nyunja RO, Netondo GW, Onyango JC. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by Sabaots of Mt Elgon Kenya. Afr J Tradit Complement Alternat Med 2010;7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Tran N, Pham B, Le L. Bioactive compounds in anti-diabetic plants: From herbal medicine to modern drug discovery. Biology. 2020;9(9):252. doi: 10.3390/biology9090252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saslis-Lagoudakis CH, Hawkins JA, Greenhill SJ, Pendry CA, Watson MF, Tuladhar-Douglas W, Baral SR, Savolainen V. The evolution of traditional knowledge: environment shapes medicinal plant use in Nepal. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2014;281(1780):20132768. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kutal DH, Kunwar RM, Uprety Y, et al. Selection of medicinal plants for traditional medicines in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17(59):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00486-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekalo TH, Woodmatas SD, Woldemariam ZA. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in the lowlands of Konta Special Woreda, southern nations, nationalities and peoples regional state. Ethiop J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2009;5:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha K. Dictionary of Nepalese plant names. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stepp JR, Moerman DE. The importance of weeds in ethnopharmacology. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;75(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poncet A, Schunko C, Vogl CR, Weckerle CS. Local plant knowledge and its variation among farmer’s families in the Napf region. Switz J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00478-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quinlan MB, Quinlan RJ. Modernization and medicinal plant knowledge in a Caribbean horticultural village. Med Anthropol Q. 2007;21(2):169–192. doi: 10.1525/maq.2007.21.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acharya T, Dhungana GK, Traille K, Dhakal H. Senior Citizens in Nepal: Policy Gaps and Recommendations. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2023;9:23337214231179902. doi: 10.1177/23337214231179902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghimire SK, McKey D, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y. Conservation of Himalayan medicinal plants: harvesting patterns and ecology of two threatened species, Nardostachys grandiflora DC. and Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora (Pennell) Hong. Biol Conserv. 2005;124(4):463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stagg BC, Dillon J. Plant awareness is linked to plant relevance: a review of educational and ethnobiological literature (1998–2020) Plants, People, Planet. 2022;4(6):579–592. doi: 10.1002/ppp3.10323. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haack BN, Rafter A. Urban growth analysis and modeling in the Kathmandu Valley. Nepal Habitat Int. 2006;30(4):1056–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.habitatint.2005.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rana D, Bhatt A, Lal B, Parkash O, Kumar A, Uniyal SK. Use of medicinal plants for treating different ailments by the indigenous people of Churah subdivision of district Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, India. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23:1162–1241. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00617-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pathy KK, Flavien NB, Honoré BK, Vanhove W, Van Damme P. Ethnobotanical characterization of medicinal plants used in Kisantu and Mbanza-Ngungu territories, Kongo-Central Province in DR Congo. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13002-020-00428-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Junsongduang A, Kasemwan W, Lumjoomjung S, Sabprachai W, Tanming W, Balslev H. Ethnomedicinal knowledge of traditional healers in Roi Et, Thailand. Plants. 2020;9(9):1177. doi: 10.3390/plants9091177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rahman MH, Roy B, Chowdhury GM, Hasan A, Saimun MS. Medicinal plant sources and traditional healthcare practices of forest-dependent communities in and around Chunati Wildlife Sanctuary in southeastern Bangladesh. Environ Sustain. 2022;5(2):207–241. doi: 10.1007/s42398-022-00230-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hardiman D. Healing, medical power and the poor: contests in tribal India. Econ Polit Wkly 2007; 1404–1408.

- 56.Ouma A. Intergenerational learning processes of traditional medicinal knowledge and socio-spatial transformation dynamics. Front Sociol. 2022;7:661992. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2022.661992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data used in this study are used in the manuscript.