Abstract

The minority stress model has been influential in guiding research on sexual and gender minority health and well-being in psychology and related social and health sciences. Minority stress has theoretical roots in psychology, sociology, public health, and social welfare. Meyer provided the first integrative articulation of minority stress in 2003 as an explanatory theory aimed at understanding the social, psychological, and structural factors accounting for mental health inequalities facing sexual minority populations. This article reviews developments in minority stress theory over the past two decades, focusing on critiques, applications, and reflections on its continued relevance in the context of rapidly changing social and policy contexts.

Keywords: Stress, Sexual minority, Gender minority, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Health, Well-being

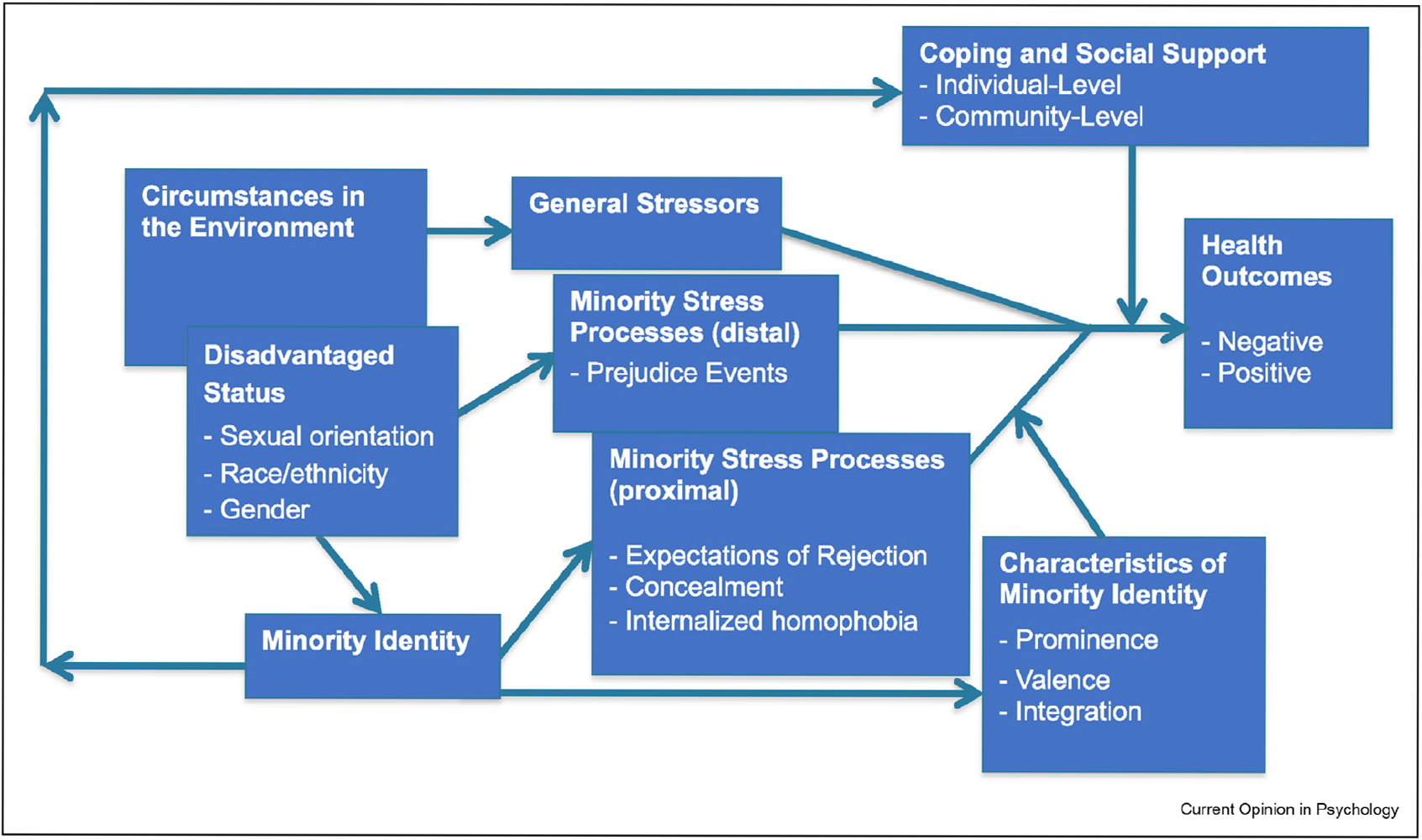

The minority stress model has been influential in guiding research on sexual and gender minority health and well-being in psychology and related social and health sciences [1]. With theoretical roots in psychology, sociology, public health, and social welfare, Meyer [2] provided the first integrative articulation of minority stress as an explanatory theory aimed at understanding the social, psychological, and structural factors accounting for mental health inequalities facing sexual minority populations (Figure 1). Here we review recent developments in minority stress theory over the past two decades, focusing on critiques, applications, and reflections on its continued relevance in the context of rapidly changing social and policy contexts.

Figure 1:

The minority stress model (Meyer, 2003).

Overview

The foundation of minority stress theory lies in the hypothesis that sexual minority health disparities are produced by excess exposure to social stress faced by sexual minority populations due to their stigmatized social status (relative to heterosexual populations). Since its introduction, which focused on sexual minorities, minority stress theory has been expanded to include gender minorities [3–5] in particular describing the role of gender non-affirmation as a stressor for transgender and nonbinary people [6].

Minority stress is distinguished from general stress—stress that all people may experience—by its origin in prejudice and stigma. Thus, a stressor, such as losing one’s job, could be a general stressor or a minority stressor depending on whether it was motivated by prejudice against sexual and gender minority people as opposed to, for example, economic downturns that impact all people regardless of sexual and gender identity.

Meyer [2] described both distal and proximal stress processes. Distal stressors include stressors that originate from people or institutions that impact the LGBT person. These include discriminatory policies and laws [7] acute major life events (e.g., losing a job, being victimized by violence) [8], chronic stressors (e.g., living in poverty) [9], more minor, “everyday” experiences of discrimination or microaggressions (e.g., being treated unfairly or with disrespect) [10], or even non-events—expected positive experiences or events that were thwarted due to stigma and prejudice [11].

Proximal stressors arise from a socialization process in which sexual and gender minority people learn to reject themselves for being LGBT (internalized stigma) [12,13], develop expectations to be stigmatized due to awareness of prevailing social stigma (expectations of rejection) [14], and/or hide their LGBT identity as a way to protect themselves against distal minority stressors (identity concealment) [15]. Concealment may be protective in some environments, but it also limits access to social support and affirmation, complicating its role in minority stress theory [15].

Collectively, these minority stressors constitute the excess stress burden that places sexual and gender minority people at greater risk for negative health outcomes compared with cisgender straight people. Against these stressors, there are individual- and group-level coping mechanisms that can reduce the negative impact of minority stress. Thus, the overall health impact in the minority stress model is determined by the negative impact of stressful experiences and the ameliorative impact of coping, social support, and resilience.

Extensions

Since its publication [2], several important extensions have been made to minority stress theory. As noted, the theory has been applied to gender minorities [16]. For example, scholars have noted the importance of recognising the unique role of cisnormativity in shaping the minority stress experiences of gender minority individuals along with how misgendering and identity invalidation represent unique minority stressors for nonbinary people [17,18] that were not originally accounted for in the model designed to explain mental health inequalities based on sexual orientation.

The minority stress model has been expanded [19] to include consideration of psychological mediation processes that explain how stigma “gets under the skin.” Stigma-related stress leads to increase in emotion dysregulation, social/interpersonal problems, and cognitive processes conferring risk for psychopathology. For example, rumination—a component of emotion dysregulation in the psychological mediation framework—has been demonstrated to mediate the impact of minority stressors on depression in a recent longitudinal study [20].

Minority stress has also been applied more widely to understand physical health outcomes via physiological stress pathways [21–23]. This literature is still young and showing mixed results. A recent systematic review found that less than half of the studies testing relationships between minority stressors and physical health found statistically significant associations between an indicator of minority stress and a biological outcome [21]. These mixed results are possibly due to lack of theoretical understanding of the stress—health relationship and lack of specification of which measures best capture this relationship. For example, different studies have used limited to measures of only one or a few forms of minority stress and health outcomes. Thus, the examination of varied outcomes and stress processes across several studies may obscure some important associations that greater specification may show [21].

While stress has traditionally been studied as an individual variable, an important expansion to understanding how stress proliferates in dyadic relationships has developed in the application of minority stress to the study of couples [24,25]. For example, LeBlanc and Frost [24] showed that couple-level minority stress was associated with multiple mental health outcomes through minority stress expansion and minority stress contagion between partners in same-sex couples. Further, minority stress experienced at the couple-level predicted mental health outcomes above and beyond individual-level minority stress experienced by each partner as individuals [24].

Applications

The hypothesized causal pathways in the minority stress model can be used to guide targeted interventions at multiple levels [26]. For example, the model has been applied to interventions in both public policy—aimed at reducing stigma and exposure to minority stress—and clinical/counseling protocols—aimed at improving individuals’ abilities to resist and increase resilience in the face of minority stress [27]. At the policy level, evidence from research on minority stress has been used in several high-impact court cases and legislative efforts in the US and elsewhere. Minority stress theory—along with the growing body of evidence that supports its central premises—has been used in a variety of ways to demonstrate the harm caused by stigma, prejudice, and discrimination against sexual and gender minority individuals (e.g., employment discrimination), couples (e.g., same-sex marriage), and families (e.g., same-gender parent adoption). This has taken the form of expert witness testimony provided by psychologists and other social scientists [28]. It has also featured in briefs submitted by professional organizations and research collectives [29,30] that have been cited by judges in providing the foundation for their rulings.

Minority stress has informed important clinical and counseling interventions designed specifically to target the mechanisms specified in the minority stress model in order to interrupt the deleterious impact of minority stress on sexual and gender minority health and well-being and inform school-based interventions [31,32]. Pachankis [33] identified “overarching treatment principles” stemming from the minority stress model, which have been successfully used in interventions designed to address syndemic conditions experienced by gay and bisexual men and alcohol misuse among sexual minority women [34,35]. For example, the first principle that “mood and anxiety symptoms are normal responses to minority stress” informs the first of a 10-module protocol designed to “normalize the experience of depression and anxiety for sexual minorities by explaining that research suggests they are more likely to experience depression and anxiety than heterosexual persons given their disproportionate exposure to stigma-related stress” (p. 287) [36]. The minority stress model has also featured prominently in the American Psychological Association’s guidance for practice with sexual minority persons [37], providing the theoretical foundation for the guidance along with intersectionality and affirmative psychology.

Although most of the research on minority stress theory has been conducted in the US and other Western contexts, a growing body of research has extended the theory to explain health and well-being outcomes among sexual and gender minority populations in other regions and cultural contexts. Comparative research using a cross-cultural perspective has provided initial evidence for the robustness of the minority stress model in explaining mental health outcomes for gay and bisexual men [38]. However, research has also highlighted the need to incorporate culturally specific processes and components into the model in order to improve its relevance outside of Western context. For example, Sun and colleagues [39] demonstrated how “certain collectivistic values (e.g., norm conformity) may exacerbate minority stress” (p. 534) for sexual minority men China, echoing calls for further work into cultural variability in the experience of minority stress and its association with health and well-being [40].

Critiques

Despite the many applications and extensions previously discussed, the minority stress model has also been subject to some critiques over the past two decades. Although the model did originally include positive health outcomes and the role of coping and stress buffering processes at the individual, social, and group levels, one critique suggests that the theory operates from a deficit-based approach without sufficient attention to positive outcomes and resilience among sexual and gender minority populations [41]. Scholars have noted that the model does not address key components of positive well-being and resilience resources, which are receiving an increased amount of attention in the field of sexual and gender minority health [42]. In response to this critique, Meyer [43] has noted that “researchers should also be cognizant of perils of a positive psychology perspective when it focuses too strongly on individual strengths and less on the institutional investments required to support individuals” (p. 349).

A similar line of criticism has been advanced by Diamond and Alley [44] who suggested that researchers consider not minority stress but the lack of social safety as a cause of sexual and gender minority health inequalities. Social safety refers to “social connection, social inclusion, social protection, social recognition, and social acceptance” (p. 5). Social safety is an important potential determent of well-being, which can be compromised by stigma. This represents is an augmentation of aspects of the stress processes originally specified in the minority stress model. Diamond and Alley contend that their suggested social safety processes are different than the social support and coping processes described in the minority stress model because they do not consider them as ameliorative (interactive) effects but as having a direct impact on health. Others have also noted the direct effect of social support and other forms of coping—including the group-level coping resource of community connectedness—on health suggesting the original model be expanded to include these pathways [45].

A genetic hypothesis argues that there is a common genetic cause underlying both sexual minority status and elevated mental health problems, which is, at least in part, responsible for the observed health inequalities based on sexual orientation [46]. It is important to note that this critique does not suggest that a genetic explanation replaces minority stress entirely as an explanation of health inequalities [47]. Although this debate continues, the evidence for a genetic role in sexual orientation and mental health is circumstantial and no evidence has been provided demonstrating a causal influence of genetic factors on both sexual orientation and mental health [48].

Continued relevance

Critics have also argued that the many improvements in the U.S. and other countries’ social climates (e.g., increasing acceptance and positive attitudes towards sexual and gender minorities) and policy (e.g., marriage equality, legal recognition of gender identities that differ from sex assigned at birth) have rendered minority stress less impactful. For example, McCormack [49] argued that homophobia is on the decline, citing policy changes, data from opinion polls, and ethnographic research in UK schools concluding that homophobia is discouraged resulting in positive experiences for sexual and gender minority youth. Similarly, drawing on interviews with sexual minority men in the US, Savin-Williams [50] argued that sexual minority men have experiences of developing sexual minority identities that involve some difficulties in managing heteronormativity and homophobia, but are largely characterized by resilience, positive mental health and well-being, and the normalization of being “gay” as only one aspect of their identities rather than a central or defining characteristic. Arguments such as these suggest the social environment for sexual and gender minorities is becoming one characterised by normalization and inclusion, and further suggests a largely positive experience for young people coming of age in such environments compared to previous generations.

However, there is little evidence from population studies that suggests this to be the case. Studies have shown that young sexual minority people experience as much or more minority stressors as did their older peers and suffer related mental health outcomes [8]. Health inequalities persist between sexual and gender minority populations and their cisgender straight peers with some studies showing that health inequalities are even more pronounced for younger sexual and gender minorities than they have been for previous generations [51]. Further evidence indicates that exposure to minority stress remains a significant concern in the lives of sexual and gender minority individuals. For example, federal monitoring shows an increase in hate crimes against sexual and gender minorities [52,53] and anti-transgender laws and violence have been on the rise in the U.S. in recent years. School surveys also show young sexual and gender minority individuals continue to experience high levels of bullying and name calling [54].

Despite the continued threat of minority stress, sexual and gender minority people are coming out about their sexual and gender identities at early ages as compared with their older peers [8]. This leads to a “developmental collision” [55] wherein younger sexual minorities can be exposed to minority stress at young ages when they may be more vulnerable to its negative effects on health and well-being than were their older peers when they were exposed to similar stressors.

Researchers have cautioned against being overly optimistic after improvements in the social and policy climates take effect. As Fish [56] and other scholars have noted, recent successes in improving the social and policy climate are necessary for promoting inclusion and protecting the health and well-being of sexual minorities, but these successes are not sufficient to eliminate minority stress and related health and well-being inequalities. The need for more research and effective interventions designed to reduce minority stress and protect and promote sexual and gender minority health remains urgent despite these important social changes. This will require continued attention to minority stress theory, along with further development and refinement as an explanatory framework for sexual and gender minority health and well-being in the context of social change.

Conclusions

In the 20 years since its articulation in Psychological Bulletin [2], minority stress theory has been highly influential in guiding research about sexual and gender minority health and well-being. It has generated international impact in guiding policy reform, alongside community and individual health interventions. Work on minority stress and health continues to innovate and address new and understudied areas. Among these are research specifying the role of community connectedness as a stressor, health enhancing factor, or moderator of stress [45,57], and understanding minority stressors at the intersection of race/ethnicity and other social statuses [58]. Despite significant social changes in the more than 50 years since Stonewall and the beginning of the modern LGBT rights movements, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination continue to impact the lives of LGBT people. Thus, minority stress theory continues to be a relevant and useful framework for understanding and improving the health and well-being of sexual and gender minority populations.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Nothing to declared

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

- [1].National Academies of Sciences: Engineering, and medicine, understanding the well-being of LGBTQI+ populations. 2020, 10.17226/25877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].*. Meyer IH: Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Psychol Bull 2003, 129:674–697. First integrative review, meta-analysis, and integrative articulation of minority stress theory as an explanation for mental health inequalities faced by sexual minority individuals.

- [3].Bockting W, Coleman E, Deutsch MB, Guillamon A, Meyer I, Meyer 3rd W, Reisner S, Sevelius J, Ettner R: Adult development and quality of life of transgender and gender nonconforming people. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016, 23:188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].*. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ: A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority stress model. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2012, 43:460. Key extension of minority stress model to gender minority (e.g., transgender and non-binary gender) individuals.

- [5].White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE: Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med 2015, 147:222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sevelius J, Chakravarty D, Neilands TB, Keatley J, Shade SB, Johnson MO, Rebchook G: Evidence for the model of gender affirmation: the role of gender affirmation and healthcare empowerment in viral suppression among transgender women of color living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2019:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hatzenbuehler ML: Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol 2016, 71: 742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meyer IH, Russell ST, Hammack PL, Frost DM, Wilson BD: Minority stress, distress, and suicide attempts in three cohorts of sexual minority adults: a US probability sample. PLoS One 2021, 16, 0246827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Frost DM, Fine M, Torre ME, Cabana A: Minority stress, activism, and health in the context of economic precarity: results from a national participatory action survey of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and gender nonconforming youth. Am J Community Psychol 2019, 63: 511–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, Davidoff KC: Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: a review of the literature. J Sex Res 2016, 53:488–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Frost DM, LeBlanc AJ: Nonevent stress contributes to mental health disparities based on sexual orientation: evidence from a personal projects analysis. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84:557–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jaspal R, Lopes B, Rehman Z: A structural equation model for predicting depressive symptomatology in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic gay, lesbian and bisexual people in the UK. Psychol Sexuality 2021, 12:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liang Z, Huang YT: Strong together”: minority stress, internalized homophobia, relationship satisfaction, and depressive symptoms among Taiwanese young gay men. J Sex Res 2022, 59:621–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Douglass RP, Conlin SE, Duffy RD: Beyond happiness: minority stress and life meaning among LGB individuals. J Homosex 2020, 67:1587–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].*. Pachankis JE, Mahon CP, Jackson SD, Fetzner BK, Bränström R: Sexual orientation concealment and mental health: a conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 2020, 146:831. Meta-analysis of associations between concealment—a proximal minoirty stressor—and mental health outcomes.

- [16].Tan KK, Treharne GJ, Ellis SJ, Schmidt JM, Veale JF: Gender minority stress: a critical review. J Homosex 2019, 67: 1471–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Johnson KC, LeBlanc AJ, Deardorff J, Bockting WO: Invalidation experiences among non-binary adolescents. J Sex Res 2020, 57:222–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Matsuno E, Bricker NL, Savarese E, Mohr R Jr, Balsam KF: The default is just going to be getting misgendered”: minority stress experiences among nonbinary adults. Psychol Sexual Orientation Gender Diversity 2022, 10.1037/sgd0000607. Advance Online Publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hatzenbuehler ML: How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull 2009, 135:707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sarno EL, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B: Rumination longitudinally mediates the association of minority stress and depression in sexual and gender minority individuals. J Abnorm Psychol 2020, 129:355–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].*. Flentje A, Heck NC, Brennan JM, Meyer IH: The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med 2020, 43:673–694. Systematic review of associations between minority stress and physcial health outcomes.

- [22].Frost DM, Lehavot K, Meyer IH: Minority stress and physical health among sexual minority individuals. J Behav Med 2015, 38:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL: Minority stress and physical health among sexual minorities. Perspect Psychol Sci 2013, 8:521–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].*. LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM: Couple-level minority stress and mental health among people in same-sex relationships: extending minority stress theory. Soc Ment Health 2019, 10: 276–290. Study examining additional impact of couple-level minoity stress on mental health among same-sex couples, above and beyond individual minoity stress.

- [25].Rostosky SS, Riggle EDB: Same-sex relationships and minority stress. Curr Opin Psychol 2017, 13:29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Meyer IH, Frost DM: Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. In Handbook of psychology and sexual orientation. Edited by Patterson CJ, Augelli AR, Oxford University Press; 2013:252–266. [Google Scholar]

- [27].*. Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE: What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit. J Soc Issues 2017, 73:586–617. Comprehensive review of minority stress interventions across multiple levels.

- [28].Russia B, No, 67667/09, Declaration of Ilan H. Meyer, Ph.D. in the Cases of Bayev V, Russia. (n.d.). https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Testimony-Bayev-Russia-May-2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mills K, APA’s role in striking down prohibitions on same-sex marriage, APA Monit. (n.d.). [Google Scholar]

- [30].American Psychological Association: 303 creative v. Elenis: amicus brief. 2022. https://www.apa.org/about/offices/ogc/amicus/elenis.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Alessi EJ: A framework for incorporating minority stress theory into treatment with sexual minority clients. J Gay Lesb Ment Health 2014, 18:47–66. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Heck NC: The potential to promote resilience: piloting a minority stress-informed, GSA-based, mental health promotion program for LGBTQ youth. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2015, 2:225–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pachankis JE: A transdiagnostic minority stress treatment approach for gay and bisexual men’s syndemic health conditions. Arch Sex Behav 2015, 44:1843–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pachankis JE, McConocha EM, Clark KA, Wang K, Behari K, Fetzner BK, Lehavot K: A transdiagnostic minority stress intervention for gender diverse sexual minority women’s depression, anxiety, and unhealthy alcohol use: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2020, 88:613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, Parsons JT: LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: a randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 2015, 83:875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Burton CL, Wang K, Pachankis JE: Psychotherapy for the spectrum of sexual minority stress: application and technique of the ESTEEM treatment model. Cognit Behav Pract 2019, 26:285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].American Psychological Association: APA task force on psychological practice with sexual minority persons. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sattler FA, Lemke R: Testing the cross-cultural robustness of the minority stress model in gay and bisexual men. J Homosex 2019, 66:189–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].*. Sun S, Hoyt WT, Tarantino N, Pachankis JE, Whiteley L, Operario D, Brown LK: Cultural context matters: testing the minority stress model among Chinese sexual minority men. J Counsel Psychol 2021, 68:526. Study suggesting extension/modification of the minoity stress model in Chinese cultural context.

- [40].Baiocco R, Scandurra C, Rosati F, Pistella J, Ioverno S, Bochicchio V, Chang TS: Minority stress, resilience, and health in Italian and Taiwanese LGB+ people: a cross-cultural comparison. Curr Psychol 2023, 42:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vaughan MD, Rodriguez EM: LGBT strengths: incorporating positive psychology into theory, research, training, and practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2014, 1:325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim HJ, Lehavot K, Walters KL, Yang J, Muraco A: The health equity promotion model: reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2014, 84:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meyer IH: Minority stress and positive psychology: convergences and divergences to understanding LGBT health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2014, 1:348. [Google Scholar]

- [44].*. Diamond LM, Alley J: Rethinking minority stress: a social safety perspective on the health effects of stigma in sexually-diverse and gender-diverse populations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022, 138, 104720. Offers alternative perspective, advancing social saftey as a critique of minoity stress model.

- [45].*. Frost DM, Meyer IH, Lin A, Wilson BD, Lightfoot M, Russell ST, Hammack PL: Social change and the health of sexual minority individuals: do the effects of minority stress and community connectedness vary by age cohort? Arch Sex Behav 2022:1–18. Study using US representative and longitudinal data from 3 generations of sexual minorities examining potential impact of social change on relationship between minority stress and health.

- [46].Bailey JM: The minority stress model deserves reconsideration, not just extension. Arch Sex Behav 2020, 49: 2265–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Zietsch BP, Verweij KJ, Heath AC, Madden PA, Martin NG, Nelson EC, Lynskey MT: Do shared etiological factors contribute to the relationship between sexual orientation and depression? Psychol Med 2012, 42:521–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].*. Meyer IH, Pachankis JE, Klein DN: Do genes explain sexual minority mental health disparities? Arch Sex Behav 2021, 50: 731–737. Engagement with genetic hypothesis for health inequalities based on sexual orientation and critique of minority stress theory.

- [49].McCormack M: The declining significance of homophobia. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Savin-Williams RC: Becoming who I am: young men on being gay. Harvard University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Fish JN, Baams L: Trends in alcohol-related disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from 2007 to 2015: findings from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. LGBT Health 2018, 5:359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].United States Department of Justice: Federal bureau of investigation. Hate Crime Statistics; 2021. 2020, https://crime-data-explorer.app.cloud.gov/pages/downloads. Accessed 12 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Flores AR, Stotzer RL, Meyer IH, Langton LL: Hate crimes against LGBT people: national crime victimization survey, 2017–2019. PLoS One 2022, 17, 0279363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kann L: Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2017. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Fish JN, Russell ST: The paradox of progress for sexual and gender diverse youth. Current Opinion in Psychology 2022, 48, 101498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Fish JN: Future directions in understanding and addressing mental health among LGBTQ youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2020, 49:943–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Rogers ML, Hom MA, Janakiraman R, Joiner TE: Examination of minority stress pathways to suicidal ideation among sexual minority adults: the moderating role of LGBT community connectedness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2021, 8:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Bowleg L, Malekzadeh AN, AuBuchon KE, Ghabrial MA, Bauer GR: Rare exemplars and missed opportunities: intersectionality within current sexual and gender diversity research and scholarship in psychology. Curr Opin Psychol 2023, 49, 101511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.