Abstract

Streptomyces coelicolor Müller contains two superoxide dismutases (SODs), nickel-containing (NiSOD) and iron- and zinc-containing SOD (FeZnSOD). The sodF gene encoding FeZnSOD was isolated by using PCR primers corresponding to the N-terminal peptide sequence of the purified FeZnSOD and a C-terminal region conserved among known FeSODs and MnSODs. The deduced amino acid sequence exhibited highest similarity to Mn- and FeSODs from Propionibacterium shermanii and Mycobacterium spp. The transcription start site of the sodF gene was determined by primer extension. When the sodF gene was cloned in pIJ702 and introduced into Streptomyces lividans TK24, it produced at least 30 times more FeZnSOD than the control cells. We disrupted the sodF gene in S. lividans TK24 and found that the disruptant did not produce any FeZnSOD enzyme activity but produced more NiSOD. The expression of the cloned sodF gene in TK24 cells was repressed significantly by Ni, consistent with the regulation pattern in nonoverproducing cells. This finding suggests that the cloned sodF gene contains the cis-acting elements necessary for Ni regulation. When the sodF mRNA in S. coelicolor Müller cells was analyzed by S1 mapping of both 5′ and 3′ ends, we found that Ni caused a reduction in the level of monocistronic sodF transcripts. Ni did not affect the stability of sodF mRNA, indicating that it regulates transcription. S. lividans TK24 cells overproducing FeZnSOD became more resistant to oxidants such as menadione and lawsone than the control cells, suggesting the protective role of FeZnSOD. However, the sodF disruptant survived as well as the wild-type strain in the presence of these oxidants, suggesting the complementing role of NiSOD increased in the disruptant.

In aerobic organisms, reactive oxygen species such as superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical are produced as by-products of normal metabolism. They are also generated when cells are exposed to environmental insults including redox-cycling agents and radiation. To protect cells against oxidative stresses caused by reactive oxygen species, living organisms have evolved complex oxidative defense and repair systems (10, 13). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is considered one of the key enzymes in the oxidative defense system, catalyzing the conversion of superoxide anion to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen. The reaction is catalyzed by cyclic oxidation and reduction of the transition metal in the active site of SODs (13). Depending on the type of metal cofactors, SODs are classified into four groups: MnSOD containing manganese, FeSOD containing iron, CuZnSOD containing copper and zinc, and NiSOD containing nickel (22, 46, 47).

Most bacteria possess two types of SODs in the cytosol, mostly FeSOD and MnSOD. They are either dimers or tetramers of identical subunits and have nearly identical primary sequences and tertiary structures, suggestive of evolution from a common ancestor (18). Despite the structural similarity, most of them have strict metal specificity (45). However, several bacteria such as Propionibacterium shermanii, Streptococcus mutans, and Bacteroides gingivalis were found to use the same apoprotein to produce either active MnSOD or FeSOD (2, 28, 29). This type of SOD is called cambialistic SOD. FeSOD and MnSOD have no similarity in sequence and structure with CuZnSOD, suggestive of independent evolution. Periplasmic CuZnSOD has been found in several bacteria, including Photobacterium leiognathi, Caulobacter crescentus, Escherichia coli, and some pseudomonads (5, 11, 39–41). NiSOD, which has been purified from several Streptomyces spp., is distinct from the above three groups of SODs on the basis of amino acid composition, N-terminal amino acid sequence, and immuno-cross-reactivity (22, 46, 47).

The regulation of expression of SOD genes has been characterized in several bacteria (45). In E. coli, the expression of the MnSOD gene (sodA) is induced by oxygen and markedly increases in response to paraquat, a superoxide-generating agent (45). The regulation is exerted both transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally (44). The transcriptional regulation of MnSOD is mediated by several global regulators such as SoxRS, Fur, Fnr, ArcA, and integration host factor (8, 45). In contrast, the transcription of the FeSOD gene (sodB) is mostly constitutive and thus far has been suggested to be regulated only by the fur locus (31). On the other hand, the periplasmic CuZnSOD increases at least 100-fold during the stationary phase partly due to the increase in transcription (19). Regarding the role of each SOD in the bacterial cell, it is suggested that MnSOD and FeSOD protect cells against superoxide originating from intracellular sources, whereas periplasmic CuZnSOD protects cells against external superoxide, judged from its localization (35). It is not certain whether the two cytosolic SODs are functionally equivalent. A study using controlled expression of E. coli MnSOD and FeSOD genes from an inducible promoter suggested that MnSOD is more effective in preventing DNA damage whereas FeSOD is more effective in protecting superoxide-sensitive enzymes (16). It has been suggested that in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, FeSOD is needed more than MnSOD for aerobic growth (14).

Streptomyces coelicolor contains NiSOD and FeZnSOD in the cytosol (22). Purified FeZnSOD is a homotetramer of 22.2-kDa subunits containing 0.36 mol of iron and 0.26 mol of zinc per mol of subunit. Its N-terminal amino acids and enzymatic characteristics suggest that it is similar to either FeSOD or MnSOD. We have found that expression of the two SODs in S. coelicolor is regulated by Ni in such a way that Ni induces NiSOD expression and represses FeZnSOD expression (22, 23). To understand the regulation of FeZnSOD at more defined levels of gene expression, we have isolated the gene (sodF) encoding FeZnSOD and analyzed its expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

S. coelicolor ATCC 10147 (Müller) and Streptomyces lividans TK24 cells were grown as described previously (17, 22). For liquid culture, YEME (1% glucose, 0.5% Bacto Peptone, 0.3% malt extract, 0.3% yeast extract, 10% sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2), YEMES (YEME plus 0.5% soytone), and YEG (1% yeast extract, 1% glucose) were used. Liquid medium was inoculated with a dense spore suspension (>107 spores/40 to 100 ml) and incubated for 20 to 40 h at 30°C with vigorous shaking. For surface culture, spores were spread on R2YE agar plates (17) or nutrient agar (NA) plates (Biolife) and grown at 30°C for 3 to 4 days. Cells containing pIJ702 or its derivatives were selected and maintained in the presence of 50 μg of thiostrepton ml−1 (Sigma). E. coli DH5α and BL21(DE3)pLysS were used as hosts for cloning and the T7 polymerase-directed overexpression system (pET), respectively.

PCR.

Oligonucleotides FN (5′-CT[C/G]CC[C/G]GAGCT[C/G]CC[C/G]TACGACTAC-3′), corresponding to the N-terminal amino acids of purified FeZnSOD, and FC (5′-CT[T/G][G/C]AGGTA[G/C]GCGTGCTCCCA-3′), corresponding to the C-terminal amino acids conserved among bacterial Mn- and FeSODs, were used as 5′ and 3′ primers, respectively. The reaction mixture contained 500 nM (each) 5′ and 3′ primers, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 100 ng of genomic DNA from S. coelicolor Müller, and 0.5 U of Taq polymerase (PoscoChem) per 100 μl of Taq polymerase reaction buffer (supplied by PoscoChem). The mixture was subjected to 30 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 94°C, annealing for 1 min at 50 to 55°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C.

Construction and screening of plasmid sublibraries for the sodF gene.

Genomic DNA from S. coelicolor Müller was digested with SalI or BglII/PvuII and electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel. Several gel slices containing SalI fragments in the range of 2.7 to 3.5 kb and BglII/PvuII fragments in the range of 0.5 to 0.7 kb which hybridized with the sodF PCR fragment were cut out of the gel. The DNA was eluted and purified from each gel slice by using a Geneclean kit II (Bio101), electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel, and confirmed for hybridization with the PCR product or oligonucleotide FC. The best-hybridizing DNA fraction was ligated with pUC18 and transformed into E. coli DH5α. Transformants were screened by colony hybridization as described by Sambrook et al. (33). The overlapping clones containing a 3.2-kb SalI fragment and a 0.6-kb BglII/PvuII fragment were named pEK11 and pEK12, respectively. These two clones were found to contain the sodF open reading frame (ORF) truncated at the C and N termini, respectively. pEK13 with a 1.3-kb DNA insert encompassing the entire sodF ORF was constructed by recombining the 0.8-kb PvuII/SalI fragment from pEK11 and the 0.5-kb SalI/PvuII fragment from pEK12 into pUC18 at the SmaI site.

RNA isolation.

RNAs were isolated from S. coelicolor Müller cells grown in YEME or YEMES for 20 to 24 h as described by Hopwood et al. (17), with the following modifications: cells were resuspended in modified Kirby mixture (1% [wt/vol] sodium triisopropyl naphthalene sulfonate, 6% [wt/vol] sodium 4-aminosalicylate, 6% [vol/vol] phenol equilibrated with 10 mM Tris HCl buffer [pH 8.3] containing 0.1% 8-hydroxyquinoline) and disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell (American Instrument Co.) at 1,000 lb/in2 or sonication with a microtip (Sonics and Materials Inc.) at 25% of the maximum amplitude (600 W, 20 kHz) two to three times for 5 s.

Primer extension analysis.

One hundred micrograms of RNA and 2 pmol of FS4 primer (5′-CGGCAGTTCAGGAAGCGTGTAGAC-3′) (Fig. 1) end labeled at the 5′ end were denatured at 85°C for 15 min in 20 μl of S1 hybridization solution (40 mM PIPES [pH 6.4], 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 80% [vol/vol] formamide) and hybridized at 31.5°C for 12 h. The hybridized primer was extended by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) in the buffer supplied by the manufacturer with 5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates and 1 U of RNasin μl−1. The extended product was analyzed on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea.

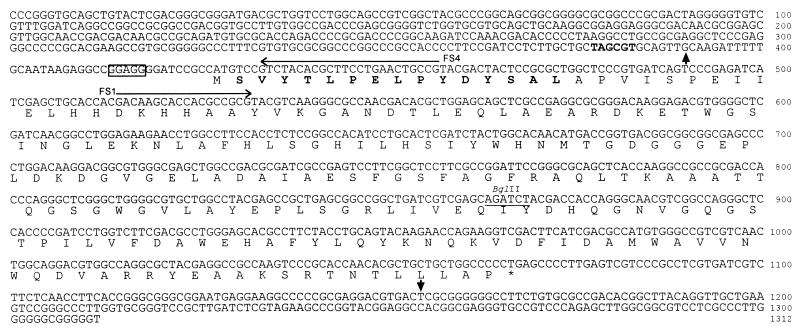

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence of the sodF gene encoding FeZnSOD from S. coelicolor Müller. The nucleotide sequence of the 1,312-bp DNA fragment containing the sodF gene is shown with the deduced amino acid sequence. Amino acids identical with the N-terminal peptide sequence determined by Edman degradation of purified FeZnSOD are indicated in boldface. The transcription start site determined by primer extension (Fig. 3) and the termination site determined by S1 nuclease mapping (Fig. 6B) are indicated by vertical arrows. The putative promoter element in the −10 region is indicated in boldface, and the putative ribosome binding site is boxed. The horizontal arrows above the nucleotide sequence indicate primers FS1 and FS4, used in gene disruption and primer extension analysis, respectively. The BglII site used in gene disruption is underlined.

S1 nuclease protection analysis.

32P-end-labeled S1 probes were prepared by standard methods (33). To generate an S1 probe for 5′ end mapping, pEK11-PvS, a pUC18 derivative containing the 0.8-kb PvuII/SalI fragment from pEK11, was digested with BglII and labeled with [γ-32P]ATP, using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The 0.7-kb DNA fragment end labeled at the 5′ end was released from the vector by digestion with EcoRI (in the polylinker). To prepare the S1 probe for 3′ end mapping, SalI-cut pEK12 was labeled with [α-32P]dATP and then digested with HindIII to release the 0.5-kb labeled probe. More than 105 cpm of each probe was coprecipitated with 150 μg of RNA per reaction. Hybridization and S1 nuclease digestion were done as described by Smith (37). The protected fragments were analyzed on 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea.

Detection of SOD activity.

Preparation of cell extracts, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), activity staining of SOD in the gel, and the activity assay for SOD were done as described previously (4, 22, 39). SOD activity in the nondenaturing gel was detected by its ability to deplete superoxide, which can reduce nitroblue tetrazolium (39).

Expression of the sodF gene in E. coli.

PCR was done on a pEK13 template, using a universal primer and the mutagenic primer FS3 (5′-CCGCCATGGCCGTCTACACG-3′), which corresponds to the N-terminal sequence of the sodF ORF with an NcoI site created (underlined). The PCR product was doubly digested with NcoI and HindIII and cloned into pET-21d (Novagen), generating pET-SODF3. E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS cells were transformed with pET-SODF3 or pET-21d. Freshly grown transformant cells were induced with 0.8 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h before harvest. Cell extracts were analyzed for SOD activity as described above.

Disruption of the sodF gene in S. lividans TK24.

To obtain the internal fragment of the sodF gene, PCR was done with FS1 (5′-GACAAGCACCACGCCGCG-3′) and a universal primer on pEK11-PvS DNA template, and the PCR product was digested with BglII, a unique site in the sodF ORF (Fig. 1). The internal sodF fragment from FS1 to the BglII site was cloned into pKC1139 (6) which contained a temperature-sensitive replication origin, generating pKC-ΔSODF. S. lividans TK24 cells were transformed with pKC-ΔSODF. Spores of the transformant were plated on NA medium containing 50 μg of apramycin ml−1 and incubated at 37°C for 2 days. From 3 × 105 spores plated, seven colonies survived, among which six were found to lack FeZnSOD activity. Genomic Southern hybridization confirmed the sodF gene disruption in these FeZnSOD-deficient cells.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence shown in Fig. 1 was deposited in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ database under accession no. AF012087.

RESULTS

Cloning and sequence analysis of the sodF gene encoding FeZnSOD from S. coelicolor Müller.

To isolate the gene for FeZnSOD (sodF) from S. coelicolor, we synthesized a pair of degenerate PCR primers, one (FN) corresponding to the N-terminal amino acid sequence determined by Edman degradation of the purified FeZnSOD (23) and the other (FC) corresponding to the region near the C terminus conserved among bacterial Fe- and MnSODs (Fig. 2). PCR with S. coelicolor Müller DNA as a template generated a single species of 500 bp as expected. The PCR product was subcloned into pUC18 and sequenced. The deduced amino acid sequence showed about 58% identity to SODs from mycobacteria and P. shermanii (data not shown). The cloned PCR product was used as a probe to isolate the sodF gene from S. coelicolor Müller. Genomic Southern analysis revealed that the PCR fragment hybridized to a specific fragment of S. coelicolor Müller DNA digested with either SalI or BglII/PvuII (data not shown). The hybridizing DNA containing the entire sodF ORF was cloned into pUC18, resulting in pEK13.

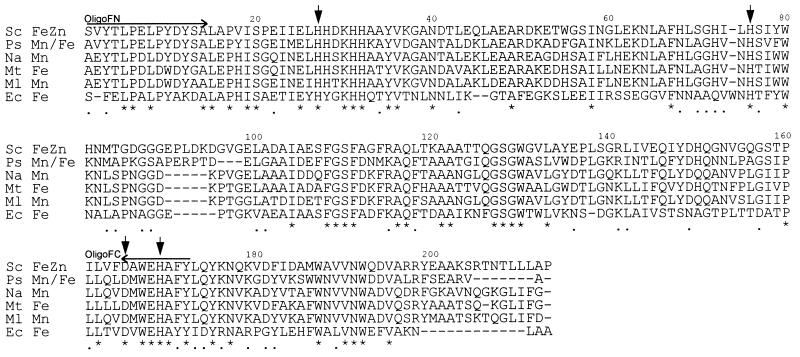

FIG. 2.

Amino acid sequence comparison of FeZnSOD with other bacterial SODs. The deduced amino acid sequence of FeZnSOD from S. coelicolor Müller (Sc FeZn) was aligned by using the ClustalV program (16) with those of cambialistic SOD from P. shermanii (Ps Fe/Mn [32]) which is active with either manganese or iron, MnSOD from Nocardia asteroides (Na Mn [1]), FeSOD from Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mt Fe [Swiss-Prot P17670]), MnSOD from Mycobacterium leprae (Ml Mn [43]), and FeSOD from E. coli (Ec Fe [35]). Identical and similar amino acids are marked with asterisks and dots, respectively. Amino acid residues proposed to be ligands for metal cofactor are indicated with vertical arrows. The horizontal arrows above the amino acid sequence indicate the two primers (oligonucleotides FN and FC [OligoFN and OligoFC]) used for PCR amplification of the sodF gene.

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the 1,312-bp DNA fragment in pEK13 are shown in Fig. 1. It contains an ORF beginning with codons for the same N-terminal peptide sequence of the purified FeZnSOD except for the initiating methionine. The predicted polypeptide with a serine at the N terminus consists of 212 residues with a predicted molecular mass of 23.4 kDa, in close agreement with the estimated size of the purified FeZnSOD protein (22.2 kDa). The deduced amino acid sequence of FeZnSOD was compared with those of other known SODs (Fig. 2). It exhibited the highest similarity (57% identity and 73% similarity) to the cambialistic SOD from P. shermanii, in agreement with the previous comparison with N-terminal peptide sequences (22). It showed about 70% similarity to either Fe- or MnSODs from Mycobacterium spp. Four residues which are known to be ligands for the metal cofactor (indicated with arrows in Fig. 2) were found at conserved positions (32, 38).

Transcription start site of the sodF gene.

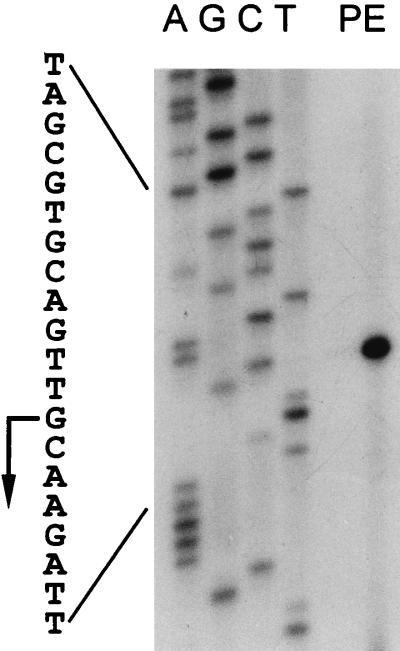

To determine the transcription start site of the sodF gene, primer extension analysis was carried out with RNAs isolated from S. coelicolor Müller cells (Fig. 3). A single species of extended cDNA of 68 nucleotides was detected with the FS4 oligonucleotide primer (Fig. 1), localizing the transcription start site to 38 nucleotides upstream from the translation start codon (Fig. 3, lane PE). A putative promoter element at the −10 region (TAGCGT) was found, similar to the consensus −10 hexamer sequence of promoters (TAGAPuT) recognized by the major sigma factor ςhrdB in S. coelicolor (Fig. 1) (20, 42). However, the sequence near the −35 region did not match any known consensus promoter sequences. A putative ribosome binding site was localized 9 nucleotides upstream from the start codon (Fig. 1).

FIG. 3.

Determination of the sodF transcription start site. Total RNAs isolated from S. coelicolor Müller cells grown in YEME were analyzed by primer extension with primer FS4 (lane PE). The DNA sequence ladder (lanes A, G, C, and T) was obtained with the same primer and plasmid pEK13, containing the entire sodF gene, as a template. Part of the DNA sequence is shown on the left, and the sodF transcription start site is indicated by a bent arrow.

Expression of the sodF gene in S. lividans and E. coli.

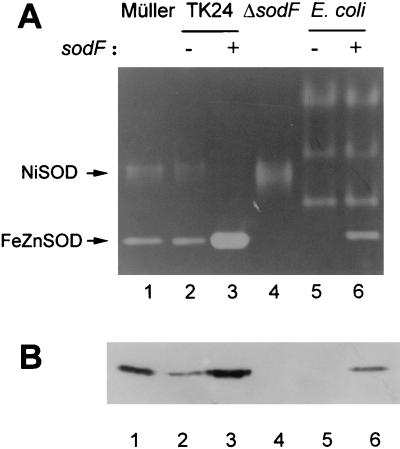

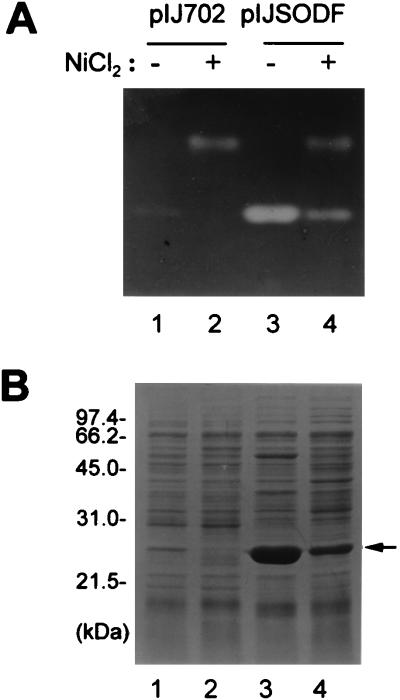

To confirm the functional expression of the sodF gene in Streptomyces, the 1.3-kb PvuII fragment containing the sodF gene from pEK13 was cloned into pIJ702 at the SacI/SphI site to generate pIJSODF and introduced into S. lividans TK24. TK24 cells contained similar SOD enzymes as S. coelicolor Müller, as demonstrated by activity staining (Fig. 4, lanes 1 and 2) and immunoblotting with antibodies against either FeZnSOD or NiSOD (data not shown). Cells containing pIJSODF produced at least 30 times more FeZnSOD activity than cells containing the parental vector (pIJ702) (Fig. 4, lanes 2 and 3). In FeZnSOD-overproducing cells, however, NiSOD expression was repressed (lane 3). Assuming high homology between the sodF genes from S. coelicolor and S. lividans, we tried disrupting the sodF gene in S. lividans TK24 as described in Materials and Methods. The disruptant cells thus obtained exhibited no FeZnSOD activity, as expected (Fig. 4, lane 4). On the other hand, the activity of NiSOD increased in the sodF disruptant cells. The expression and disruption of the sodF gene were confirmed by immunoblotting analysis (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Expression of the sodF gene product. (A) SOD activity was detected in 9% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel loaded with cell extracts (20 μg of protein per lane) from S. coelicolor Müller (lane 1), S. lividans TK24 with pIJ702 plasmid (lane 2), S. lividans TK24 with pIJSODF plasmid (lane 3), TK24 sodF disruptant (lane 4), E. coli with plasmid pET-21d (lane 5), and E. coli with plasmid pET-SODF3 (lane 6) as described in the text. Activity bands of FeZnSOD and NiSOD are indicated with arrows. (B) Proteins in the same cell extracts were blotted with mouse polyclonal antibody against purified FeZnSOD. For optimal visualization of signals, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6 were loaded with 1 μg of total protein whereas lanes 1 and 4 contained 20 μg of protein.

We next used the pET overexpression system and constructed pET-SODF3 as described in Materials and Methods. In this process, the second amino acid serine is bound to change to glycine in the expressed FeZnSOD. E. coli BL21 cells with pET-SODF3 expressed active FeZnSOD (Fig. 4, lane 6). The total SOD activity including endogenous E. coli Mn- and FeSOD in cell extracts was estimated to be 3,420 U mg−1, whereas the control cells with the parental vector produced 712 U mg−1. At most about 10% of the total soluble protein was FeZnSOD protein, as judged by scanning an SDS-polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue, and the specific activity of FeZnSOD produced in E. coli cells was thus calculated to be more than 27,000 U mg−1. This level is slightly higher than that of FeZnSOD purified from S. coelicolor Müller (20,000 U mg−1) and suggests that the sodF gene is functionally expressed in E. coli with full activity. Immunoblotting analysis confirmed the expression of sodF in E. coli and also demonstrated that there is no cross-reactivity between E. coli FeSOD and S. coelicolor FeZnSOD.

Regulation of gene expression from the cloned sodF gene by Ni in S. lividans.

We investigated whether the expression of the cloned sodF gene from S. coelicolor is regulated by Ni in S. lividans as we have observed in S. coelicolor (22). The results observed by activity staining (Fig. 5A) and SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5B) of cell extracts obtained from S. lividans TK24 cells harboring pIJSODF grown in the absence or presence of 200 μM NiCl2 demonstrate that the two SODs in S. lividans are regulated by Ni in the same way as in S. coelicolor (lanes 1 and 2). Ni caused the reduction in the amount of FeZnSOD polypeptide and its activity and an increase in the amount of NiSOD expression. TK24 cells harboring pIJSODF overproduced FeZnSOD in the absence of added Ni but produced a much reduced amount in the presence of Ni (lanes 3 and 4). This result suggests that the cloned sodF gene contains the cis-acting sequence element which responds to the repressive action of Ni.

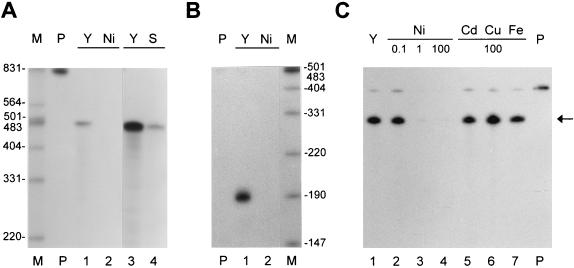

FIG. 5.

Regulation of gene expression from the cloned sodF gene by Ni. S. lividans TK24 cells containing either pIJ702 (lanes 1 and 2) or pIJSODF (lanes 3 and 4) were grown on cellophane disks overlaid on R2YE in the absence (lanes 1 and 3) or presence (lanes 2 and 4) of 200 μM NiCl2. Cell extracts (20 μg of protein per lane) were electrophoresed on a 9% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel stained for SOD activity (A) or a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (B). The protein band for FeZnSOD is indicated by an arrow; sizes are indicated in kilodaltons.

Regulation of sodF transcription in S. coelicolor Müller by nickel.

To elucidate the step(s) where Ni exerts the regulatory role in sodF gene expression, we examined the changes in sodF mRNA in S. coelicolor Müller by S1 mapping analysis. Using the S1 probe labeled at the 5′ position of the BglII-cut end, we detected an S1-protected fragment of the predicted size (480 nucleotides) in the absence of Ni (Fig. 6A, lane 1). When nickel was added to the medium (YEME), the level of sodF transcripts decreased about 30-fold within 1 h (Fig. 6A, lane 2). A similar reduction in sodF mRNA induced by Ni was observed when RNAs from cells grown in Ni-rich YEMES and Ni-deficient YEME media were analyzed (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 and 4). This finding confirms the previous observation by Kim et al. (22) of the reduced synthesis of FeZnSOD in YEMES media and demonstrates that the regulation is at the level of transcripts. When the S1 probe labeled at the 3′ end of SalI site was used, a protected fragment of 190 nucleotides was detected (Fig. 6B, lane 1). This allows the localization of the transcription termination site of the sodF gene to 90 nucleotides downstream from the translation stop codon, suggesting that sodF mRNA is monocistronic. The same extent and kinetics of reduction in sodF mRNA were observed by 3′ S1 mapping analysis (Fig. 6B, lane 2). When RNAs from S. lividans TK24 cells harboring pIJSODF were analyzed by S1 mapping, it was found that the amount of sodF transcripts decreased about 30-fold upon addition of Ni, confirming that the regulation of sodF gene expression observed in Fig. 5 also resulted from a reduction in transcripts (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Transcriptional regulation of the sodF gene by Ni. The sodF RNA was analyzed by S1 mapping of either the 5′ (A and C) or 3′ (B) end. (A and B) Total RNAs were prepared from S. coelicolor Müller cells grown in YEME without additional Ni (lane 1) or treated with 200 μM NiCl2 for 1 h (lane 2). For lanes 3 and 4, S. coelicolor Müller cells were grown in YEME (Y; lane 3) and YEMES (S; lane 4) media, and the film was overexposed. HpaII-digested pGEM3Zf DNA (A) and EcoRI/HindIII-digested λ DNA (B) were end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and used as size markers (indicated in nucleotides; lanes M). Lane P shows the S1 probe used in each reaction. (C) Cells were grown in YEME with 0.1, 1, and 100 μM NiCl2 (lanes 2 to 4), 100 μM CdCl2 (lane 5), CuCl2 (lane 6), and FeCl3 (lane 7) and were treated for 3 h before harvest.

To test the specificity of Ni in this regulation, we examined the effects of other metals, including Cd, Cu, and Fe. Figure 6C represents an S1 mapping analysis of sodF mRNA from cells treated with 0.1 to 100 μM NiCl2 or 100 μM (each) CdCl2, CuCl2, or FeCl3. The results demonstrate that Ni is effective even at 1 μM, reducing the level of sodF mRNA more than 10-fold (Fig. 6C; compare lanes 1, 2, and 3). On the other hand, Cd, Cu, and Fe had no effect in regulating the level of sodF mRNA (lanes 5 to 7).

We tested whether Ni changes the stability of mRNA by S1 mapping the 3′ end of the sodF mRNA obtained at various time intervals after treatment of S. coelicolor Müller cells with rifampin (300 μg ml−1). The result demonstrated that the half-life of sodF mRNA was about 18 min and was not affected by Ni (data not shown). This result clearly indicates that Ni specifically represses the expression of the sodF gene at the transcriptional level.

Role of FeZnSOD in protecting S. lividans cells against superoxide-generating oxidants.

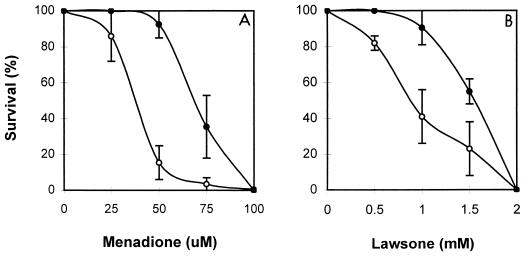

We examined the effect of overproducing or eliminating FeZnSOD on the survival of S. lividans cells upon treatment with various oxidants known to generate superoxide radicals. When spores from cells containing either pIJ702 or pIJSODF were plated on NA medium containing various concentrations of menadione or lawsone, we observed that FeZnSOD-overproducing cells survived better than the control cells (Fig. 7), suggesting that FeZnSOD plays a protective role against these oxidants. The effect of FeZnSOD overproduction was less pronounced when cell survival was tested against plumbagin (data not shown). On the contrary, the sodF disruptant survived as well as the wild type in the presence of these oxidants (data not shown). This result was not unexpected, since sodF mutant cells produced more NiSOD than the wild type. It is most likely that the increased production of NiSOD compensated for the loss of FeZnSOD in protecting cells against superoxide-generating oxidants.

FIG. 7.

Resistance of FeZnSOD-overproducing cells against superoxide-generating agents. Spores of S. lividans TK24 cells harboring pIJ702 (open circles) or pIJSODF (filled circles) were plated on NA medium containing various concentrations of menadione (A) or lawsone (B). Surviving colonies were counted after 4 days. Data are presented as averages of three independent countings with standard deviation ranges.

DISCUSSION

Most bacterial cytosolic SODs are Fe- and MnSODs which usually contain 0.5 to 1.0 g-atom of either Fe or Mn per monomeric subunit (18). However, several SODs are known to contain both Fe and Zn. They all exist as tetramers and include SODs from Methanobacterium bryantii (26), Nocardia asteroides, which also contains Mn (3), Thermoplasma acidophilum (36), and Streptomyces spp. (22, 47). FeZnSOD from S. coelicolor has been reported to exhibit typical FeSOD-like characteristics, judged from both absorption spectra and sensitivity to inhibitors (21, 22). The primary sequence of the SodF polypeptide reveals the highest similarity to the cambialistic SOD from P. shermanii and both Fe- and MnSODs from Mycobacterium spp. It has been suggested that one of the ligands for the metal cofactor can influence the metal specificity of either Mn- or FeSOD. X-ray crystallographic structure of FeSOD from Mycobacterium tuberculosis showed that the fifth ligand of iron, a hydroxide ion, interacts with His145, which is replaced with glutamine in Mycobacterium leprae MnSOD (9). In FeZnSOD of S. coelicolor Müller, histidine was found at the corresponding position, consistent with the presence of iron as the cofactor.

Expression of the two SODs in S. coelicolor has been demonstrated to be affected dramatically by the presence of Ni and metal chelators (21, 22). Ni increases and decreases the synthesis of NiSOD and FeZnSOD, respectively. The regulatory role of Ni is on the transcriptional level for both NiSOD (23) and FeZnSOD as demonstrated in this study. So far, Ni-dependent transcriptional regulation has been reported only for the hydrogenase gene expression in Bradyrhizobium japonicum (24, 25). The transcriptional regulator which responds to Ni has not yet been identified. Ni repression of the cloned sodF gene on a multicopy plasmid suggests the presence of a cis-acting regulatory site within the 1.3-kb cloned fragment. The localization of the cis-acting element is expected to allow identification of the Ni-responsive factor. Other than Ni, the depletion of Fe by chelator desferrioxamine decreases the expression of FeZnSOD (21). This finding is consistent with the observation that the sodB gene for FeSOD in E. coli is positively regulated by Fur. Since a Fur-like regulator has been recently identified in S. coelicolor (12), regulation of the sodF gene by Fe needs to be investigated further in this respect.

Expression of SODs in S. coelicolor increases only slightly (less than twofold) upon treatment with superoxide-generating oxidants such as paraquat, plumbagin, and menadione (21) and also increases about twofold in the stationary phase. This contrasts with the expression of catalase, another oxidative defense enzyme, a subset of whose isozymes increases significantly as cells enter the stationary phase, differentiate, or are treated with oxidants such as H2O2 (7, 27). Our observation suggests that the amount of SODs is rather strictly controlled in S. coelicolor, in contrast with catalases. The compensating Ni-regulated expression of NiSOD and FeZnSOD as well as the increased expression of NiSOD in a sodF disruptant supports this idea. The compensating expression of the two SODs also suggests that the two enzymes have some roles in common, at least for protecting cells against oxidants as demonstrated in the sodF disruptant. The elucidation of the specific role of each SOD requires further investigation of SOD mutants under various environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation to the Research Center for Microbiology, Seoul National University. E.-J. Kim was the recipient of the postdoctoral fellowship from the Research Institute of Basic Sciences, Seoul National University.

We thank J.-S. Choi for expert assistance in preparing antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alcendor D J, Chapman G D, Beaman B L. Isolation, sequencing and expression of the superoxide dismutase-encoding gene (sod) of Nocardia asteroides strain GUH-2. Gene. 1995;164:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00476-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano A, Shizukuishi S, Tamagawa H, Iwakura K, Tsunasawa S, Tsunemitsu A. Characterization of superoxide dismutases purified from either anaerobically maintained or aerated Bacteroides gingivallis. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1457–1463. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1457-1463.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaman B L, Scates S M, Moring S E, Deem R, Misra H P. Purification and properties of a unique superoxide dismutase from Nocardia asteroides. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauchamp C, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase: improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal Biochem. 1971;44:276–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(71)90370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benov L T, Fridovich I. Escherichia coli expresses a copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25310–25314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bierman M, Logan R, O’Brien K, Seno E T, Nagaraja Rao R, Schoner B E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho Y H, Roe J H. Isolation and expression of the catA gene encoding the major vegetative catalase in Streptomyces coelicolor Müller. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4049–4052. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.4049-4052.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Compan I, Touati D. Interaction of six global transcription regulators in expression of manganese superoxide dismutase in Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1687–1696. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.6.1687-1696.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper J B, McIntyre K, Badasso M O, Wood S P, Zhang Y, Garbe T R, Young D. X-ray structure analysis of the iron-dependent superoxide dismutase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis at 2.0 Ångstroms resolution reveals novel dimer-dimer interactions. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:531–544. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farr S B, Kogoma T. Oxidative stress responses in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:561–585. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.4.561-585.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fridovich I. Superoxide radical and superoxide dismutase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:97–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn, J. S. Unpublished data.

- 13.Halliwell B, Gutteridge J M C. Free radicals in biology and medicine. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassett D J, Schweizer H P, Ohman D E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:76330–76337. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6330-6337.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins D G, Bleasby A T, Fuchs R. CLUSTAL V: improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Comp Appl Biosci. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkin K A, Papazian M A, Steinman H M. Functional differences between manganese iron superoxide dismutases in Escherichia coli K-12. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24253–24258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, England: John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes M N, Poole R K. Metals and microorganisms. London, England: Chapman and Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imlay K R C, Imlay J A. Cloning and analysis of sodC, encoding the copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2564–2571. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2564-2571.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang J G, Hahn M Y, Ishihama A, Roe J H. Identification of sigma factors for growth phase-related promoter selectivity of RNA polymerases from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2566–2573. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.13.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim E J. Characterization of superoxide dismutases and their genes from Streptomyces coelicolor. Ph.D. thesis. Seoul, Korea: Seoul National University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim E J, Kim H P, Hah Y C, Roe J H. Differential expression of superoxide dismutases containing Ni and Fe/Zn in Streptomyces coelicolor. Eur J Biochem. 1996;241:178–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0178t.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim E J, Chung H J, Suh B, Hah Y C, Roe J H. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by nickel of sodN gene encoding nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces coelicolor Müller. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:187–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Maier R J. Transcriptional regulation of hydrogenase synthesis by nickel in Bradyrhizobium japonicum. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18729–18732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim H, Yu C, Maier R J. Common cis-acting region responsible for transcriptional regulation of Bradyrhizobium japonicum hydrogenase by nickel, oxygen, and hydrogen. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3993–3999. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.3993-3999.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirby T W, Lancaster J R, Jr, Fridovich I. Isolation and characterization of the iron-containing superoxide dismutase of Methanobacterium bryantti. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1981;210:140–148. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(81)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J S, Hah Y C, Roe J H. The induction of oxidative enzymes in Streptomyces coelicolor upon hydrogen peroxide treatment. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1013–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin M E, Byers B R, Olson M O J, Salin M L, Arceneaux J E L, Tolbert C. A Streptococcus mutans superoxide dismutase that is active with either manganese or iron as a cofactor. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9361–9367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier B, Barra D, Bossa F, Calabrese L, Rotilio G. Synthesis of either Fe- or Mn-superoxide dismutase with an apparently identical protein moiety by an anaerobic bacterium dependent on the metal supplied. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:13977–13980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meier B, Sehn A P, Schininà M E, Barra D. In vivo incorporation of copper into the iron-exchangeable and manganese-exchangeable superoxide dismutase from Propionibacterium shermanii. Eur J Biochem. 1994;219:463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niederhoffer E C, Naranjo C M, Bradley K L, Fee J A. Control of Escherichia coli superoxide dismutase (sodA and sodB) genes by the ferric uptake regulator (fur) locus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:1930–1938. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.4.1930-1938.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parker M W, Blake C C F. Crystal structure of manganese superoxide dismutase from Bacillus stearothermophilus at 2.4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1988;199:649–661. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schininà M E, Maffey L, Barra D, Bossa F, Puget K, Michelson A M. The primary structure of iron superoxide dismutase from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1987;221:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnell S, Steinman H M. Function and stationary-phase induction of periplasmic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and catalase/peroxidase in Caulobacter crescentus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5924–5929. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5924-5929.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Searcy K B, Searcy D G. Superoxide dismutase from the archaebacterium Thermoplasma acidophilum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;670:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(81)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith C P. Methods for mapping transcribed DNA sequences. In: Brown T A, editor. Essential molecular biology: a practical approach. Vol. 2. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 237–252. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stallings W C, Pattridge K A, Strong R K, Ludwig M L. The structure of manganese superoxide dismutase from Thermus thermophilus HB8 at 2.4-Å resolution. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:16424–16432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinman H M. Bacteriocuprein superoxide dismutases in pseudomonads. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:1255–1260. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.3.1255-1260.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steinman H M. Bacteriocuprein superoxide dismutase of Photobacterium leiognathi. Isolation and sequence of the gene and evidence for a precursor form. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:1882–1887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinman H M, Ely B. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase of Caulobacter crescentus: cloning, sequencing, and mapping of the gene and periplasmic location of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2901–2910. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.2901-2910.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strohl W R. Compilation and analysis of DNA sequences associated with Streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:961–974. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thangaraj H S, Lamb F I, Davis E O, Colston M J. Nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequence of Mycobacterium leprae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9378. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Touati D. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase biosynthesis in Escherichia coli, studied with operon and protein fusions. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2511–2520. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.6.2511-2520.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Touati D. Regulation and protective role of the microbial superoxide dismutases. In: Scandalios J G, editor. Molecular biology of free radical scavenging systems. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1992. pp. 231–261. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youn H D, Kim E J, Roe J H, Hah Y C, Kang S O. A novel nickel-containing superoxide dismutase from Streptomyces spp. Biochem J. 1996;318:889–896. doi: 10.1042/bj3180889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Youn H D, Youn H, Lee J W, Yim Y I, Lee J K, Hah Y C, Kang S O. Unique isozymes of superoxide dismutase in Streptomyces griseus. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;334:341–348. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]