Abstract

Mechanical foot pain affects ∽20% of the UK population >50 years of age, with ∼10% reporting disabling pain that impacts daily activities. For most people, foot pain improves over time, but for some this can become chronic and disabling, affecting physical activity, participation, mental health and work capacity. Mechanical foot pain can present as localized pain, but more often the pain presents in multiple structures. Traditional treatments for mechanical foot pain are largely based on self-management that includes pain control, reassurance of healing trajectory, and activity or footwear modifications. Randomized controlled trials support the short-term use of exercise and foot orthoses for some foot conditions; however, accessibility can be limited by regional variations in procurement compounded by a lack of long-term trials. The roles of weight loss and strengthening of the foot and leg muscles offer new avenues to explore.

Keywords: foot, pain, mechanical foot pain, epidemiology, diagnosis, exercise, foot orthoses, shoes, epidemiology, treatment, radiology

Key messages.

Mechanical foot pain is common and frequently associated with joint pain and soft tissue pain at the tendon and fascia.

The foot is complex, and the shape of the forefoot and midfoot can change in later life. The wrong size and shape of footwear, especially the toe-box, is a common cause of pain.

Modifying the foot load by pacing, wearing foot orthoses and changing footwear all have the potential to help foot pain and disability.

Introduction

Mechanical foot pain is a term used to describe musculoskeletal foot pain associated with patterns of weight-bearing movement. The prevalence of mechanical foot pain varies from 13 to 39% depending on the case definition and age range of the cohort [1]. The prevalence of disabling foot pain (pain that impacts on daily activities, such as standing, walking and climbing stairs) ranges from 8 to 10% [2, 3]. Increasing age is the greatest determinant for developing mechanical foot pain, with peak incidence between the ages of 55 and 64 years [1]. Obesity is another determinant influencing both the onset and the severity of foot pain [4] and increasing the risk of multiple lower limb pains [5]. Consistently, more women than men report disabling foot pain [6, 7]. The burden of mechanical foot pain is greater in lower socioeconomic groups [6].

Despite the high prevalence of mechanical foot pain, only 12% of people with foot pain consult primary care clinicians, reinforcing the perception that mechanical foot pain has minimal burden and impact [8–10]. The true impact is likely to be high, because 30% of people with mechanical foot pain report persistent and severe symptoms [11]. The risk factors for developing persistent and severe mechanical foot pain include excess body weight, working in manual and intermediate occupations, having poorer physical and mental health, having catastrophizing beliefs, having greater foot-specific functional limitation, and self-assessed hallux valgus [11]. The burden and impact of mechanical foot pain are greatest in lower socioeconomic groups [6], who have an increased likelihood of concomitant knee or hip pains, leading to greater physical and mental burden [12], increased frequency of general practice consultations [5] and increased likelihood of work restrictions and early retirement [13–16].

In general practice and rheumatology clinics, foot pain is often overlooked owing to barriers of performing assessment and removing footwear and hosiery in busy clinics [17]. Foot pain presentations are perceived as challenging in the more complex regions of the midfoot, hindfoot or ankle [18], and this is exacerbated by a lack of diagnostic tests and low confidence and skills shown by the medical and nursing community [19–23]. To aid clinical confidence and recognition, the most common foot conditions in regions for the forefoot, midfoot and hindfoot (for a summary, see Table 1) are presented, followed by clinical management.

Table 1.

Typical symptoms and signs of common causes of mechanical foot pain

| Region | Condition | Typical symptoms | Key signs from physical assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medial forefoot | First MTP joint OA | Pain and stiffness at the first MTP joint, difficulty bending the big toe upwards, swelling | Dorsal exostosis, tenderness with palpation of the dorsal aspect of the joint, limited range of motion (dorsiflexion) |

| Hallux valgus | Pain and swelling along medial side of first MTP joint, symptoms aggravated by prolonged weight-bearing and constrictive footwear causing joint pressure | Lateral deviation of the hallux and widening of the forefoot, may be lesser toe digital deformity and associated pressure lesions (callus), visible bump on the medial side of the first MTP joint, redness/prominence at medial aspect of first MTP joint | |

| Lateral forefoot | Inter-metatarsal bursitis | Plantar forefoot pain that may be perceived as a feeling of a lump, may be tingling or numbness | May be spreading of adjacent toes in a V-sign, positive thumb–index finger squeeze test |

| Inter-metatarsal neuroma | Plantar forefoot pain that may be perceived as a feeling of a lump, may be tingling or numbness locally or referred into the toes | Positive thumb–index finger squeeze test may cause toe numbness or tingling locally or in the toes | |

| MTP joint synovitis and plantar plate instability | Plantar forefoot pain that may be perceived as a feeling of a lump, pain when walking (toe propulsion) and difficulty with shoes feeling tight or toes rubbing | May be enlargement of the MTP joint, may be associated toe deformity, spreading of the toes, tenderness with palpation of the plantar aspect of the MTP joint. Range of motion of the MTP joint may have increased or become unstable when displaced, indicative of a plantar plate tear | |

| Midfoot | Midfoot OA |

|

Dorsal swelling, changes in bony alignment with bony exostosis. In some cases, accompanied by tenderness with palpation of the dorsal aspect of the midfoot joints |

| Midfoot sprains and strains (tendinopathies and enthesopathies) |

|

|

|

| Rearfoot | Plantar heel pain | Plantar heel pain worse with first few steps in the morning or after rest | Tenderness with palpation of medial calcaneal tubercle and hallux extension |

| Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction (adult-acquired flatfoot deformity) | Pain and swelling along medial side of foot/ankle, increasingly flat foot, and difficulty with ambulatory function | Swelling on medial side of ankle, pain with palpation of tibialis posterior muscle, weakness of tibialis posterior muscle/difficulty in performing heel rise, progressive flat foot deformity becoming increasingly fixed | |

| Tarsal tunnel syndrome | Medial arch tenderness, pain, dysesthesia, and some people report medial hindfoot swelling and tingling in the arch and or plantar midfoot | Atrophy and weakness of the medial arch abductor muscles. Loss of sensation in the tibial dermatome. Tapping the nerve posterior to the medial malleolus causes tenderness and paraesthesia. This is called a positive Tinel sign (present in 50% of cases) | |

| Achilles tendinopathy | Pain and stiffness in Achilles tendon region, aggravated by loading | Possible nodular thickening of Achilles tendon, tenderness to palpation of Achilles tendon 2–6 cm proximal to insertion (mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy) or at Achilles tendon insertion (insertional Achilles tendinopathy), pain with hopping |

Forefoot

The forefoot (defined as the toes to the mid-shaft of the metatarsal bones) is subjected to high vertical and shear stress during gait, particularly during propulsion. Consequently, the forefoot has been reported to be the most prevalent region for foot pain. The term metatarsalgia is commonly used to describe pain occurring at the plantar aspect of the forefoot [24], which can be the result of many different conditions. Common conditions affecting the medial forefoot are first MTP joint OA and hallux valgus. At the lateral forefoot, inter-metatarsal bursitis, inter-metatarsal neuroma and synovitis–effusion of the MTP joints are most common [25]. It is worth noting that the second to fifth toes and MTP joints are common sites for the onset of inflammatory arthritis, and where persistent pain and or swelling is found, further investigations are recommended.

Medial forefoot

OA

First MTP joint OA, also known as hallux rigidus, is characterized by degeneration of joint articular cartilage and bony proliferation at joint margins, but there are also changes in surrounding joint tissues, including synovitis and subchondral bone marrow oedema [26]. The condition affects 8% of people aged ≥50 years and is more prevalent in women and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds [27]. The main symptoms are localized pain and stiffness at the joint, which adversely impact foot-specific and general health-related quality of life [28].

First MTP joint OA can be diagnosed through history taking and physical assessment. Passive joint movement testing will reproduce pain with maximum dorsiflexion and is accompanied by a limitation of dorsiflexion range of motion [28]. A diagnostic model using pain duration of >25 months, the presence of a dorsal exostosis, hard end-feel, crepitus and <64° of joint dorsiflexion accurately predicted the presence of radiographic first MTP joint OA in a study of 181 people with joint pain [29]. Clinical guidelines for OA recommend radiographic assessment in cases of diagnostic uncertainty or for surgical planning [30].

Hallux valgus

Hallux valgus is characterized by the progressive subluxation of the first MTP joint owing to lateral deviation of the hallux and medial deviation of the first metatarsal. As the condition progresses, the lateral deviation of the hallux can cause compression against the second toe, leading to lesser toe deformity, callus formation and difficulty in finding comfortable footwear [31]. Hallux valgus can be accompanied by a painful soft tissue (there may be an overlying adventitious bursa from footwear pressure) and bony prominence on the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head, termed a bunion. Hallux valgus is more common in women and those >65 years of age, affecting ∼23% of people aged between 18 and 65 years [32]. This condition causes significant foot pain, disability and reduced health-related quality of life, in addition to impaired balance and increased risk of falls [32–36].

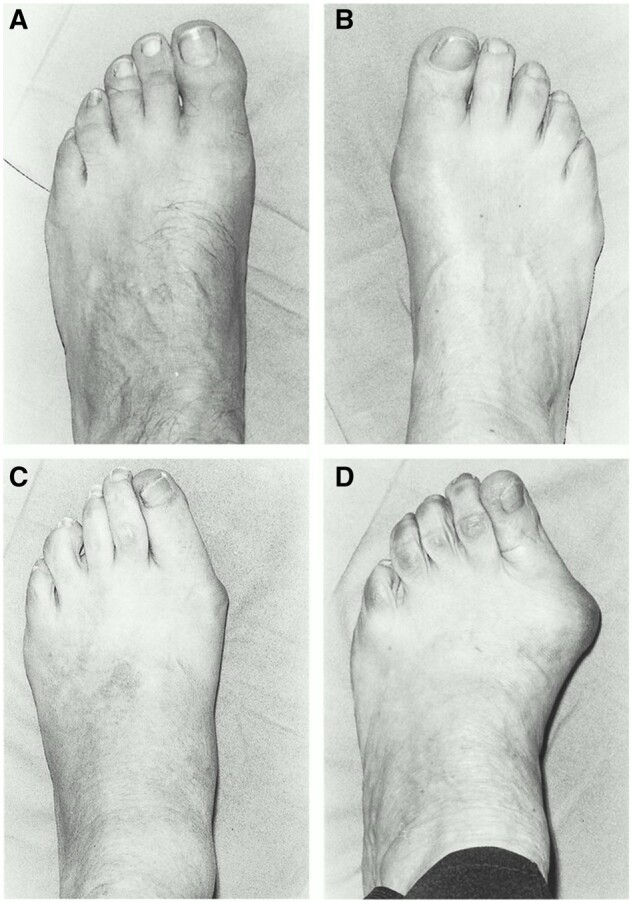

Individuals with symptomatic hallux valgus report pain at the medial aspect of the first MTP joint caused by pressure between the bunion and the shoe or between the first and second toes. These symptoms are aggravated by increased weight-bearing and use of footwear with a constrictive toe-box [31]. Physical assessment reveals varying degrees of deformity, including lateral deviation of the hallux, valgus rotation of the hallux, bony prominence and s.c. bursitis at the medial aspect of the first MTP joint, and lesser toe deformity [31]. The severity of the deformity can be assessed whilst the patient is standing, using the Manchester scale, which involves comparison the patient’s foot with a standardized set of photographs [37] (Fig. 1). Radiological assessment is not necessary, but dorsoplantar weight-bearing radiographs can confirm the presence of the condition (where hallux abductus angle is >15°) [38, 39].

Figure 1.

Manchester scale hallux valgus grading photographs. (A) Grade 1 (no deformity). (B) Grade 2 (mild deformity). (C) Grade 3 (moderate deformity). (D) Grade 4 (severe deformity). From The Grading of Hallux Valgus: The Manchester Scale, by Garrow AP, Papageorgiou A, Silman AJ, et al., JAPMA 91(2): 74–78, 2001; https://doi.org/10.7547/87507315-91-2-74. Used with permission from the American Podiatric Medical Association

Lesser forefoot

Inter-metatarsal and plantar bursitis

Within the forefoot, inter-metatarsal bursae are located between the MTP joints, dorsal to the deep transverse inter-metatarsal ligament [40]. Inter-metatarsal bursitis occurs owing to excessive friction or pressure from the surrounding tissues [41, 42]. Likewise, adventitial plantar bursitis develops in the soft tissues of the forefoot beneath the MTP joints owing to excessive shearing and pressure from the bony structures of the foot with the weight-bearing surface [42, 43].

MTP joint synovitis and instability

Inflammation of the lesser MTP joints, termed synovitis, results from excessive pressure on the plantar forefoot. Over time, the inflammation combined with continuous pressure can weaken stabilizing structures of the joint capsule, including the plantar plate and collateral ligaments. This can lead a progressive subluxation of the proximal phalanx, a condition termed plantar plate syndrome or pre-dislocation syndrome [43, 44]. The second and third MTP joints are commonly affected owing to the significant load they bear [45]. Additionally, the lesser MTP joints can be subjected to increased load owing to first MTP joint pathology or surgery [46, 47].

Inter-metatarsal neuroma

Inter-metatarsal neuromas affect the common plantar digital nerves [48]. They are not true neuromas; instead, they are benign masses composed of perineural fibrosis, local vascular proliferation and nerve degeneration [48, 49]. These lesions typically occur in the second or third web space [48]. In general practice clinics, inter-metatarsal neuroma is reported as the second most common compressive neuropathy presentation behind carpal tunnel syndrome [50], presenting more commonly in women and those aged ≥45 years [50]. Inter-metatarsal neuromas develop because of pressure on the inter-digital nerve from the metatarsal bones or deep transverse inter-metatarsal ligament. Inter-metatarsal neuromas are frequently observed in conjunction with inter-metatarsal bursitis, suggesting a possible link between the two conditions [48, 49].

Diagnosis of lesser forefoot pain

Diagnosing lesser forefoot pain based solely on history taking and a physical assessment is challenging because of the similarity in symptoms and signs for different conditions. Individuals with these conditions report localized dull or sharp pain at the plantar aspect of their forefoot that is aggravated by forefoot loading and constrictive footwear. They may also experience swelling or tingling and perceive feeling a lump beneath the forefoot, described as walking on pebbles or a ridge in the shoe [43, 48]. There may be enlargement of the MTP joint where there is moderate effusion–synovitis, deformity of the toe where pre-dislocation syndrome is present, and spreading of the toes where inter-metatarsal bursitis is present [41]. By palpating the plantar aspect of the MTP joints, immediately distal to the metatarsal head, the presence of pain can confirm MTP joint pathology. Additionally, a thumb–index finger squeeze test of the inter-metatarsal spaces has been reported to have high diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity and specificity >95%) for inter-metatarsal neuroma [51]. However, imaging through musculoskeletal US or MRI is important to confirm a specific diagnosis of lesser forefoot pathology, with high diagnostic accuracy to inform surgical opinion [43, 52].

Midfoot

Midfoot pain affects 20% of people >50 years of age, affecting more women than men, and those in a manual occupations [53]. The midfoot (defined as the area from the mid-shaft of the metatarsals to the talus neck) is a complex region supported by tarsal ligaments, intrinsic muscles and fascia. The midfoot is subjected to mechanical load placed on the arch span during standing and walking. This can be exacerbated by age [54], changes in body weight, pregnancy and muscle fatigue, which are associated with greater midfoot pain and higher plantar pressures [55–58].

Midfoot OA

Symptomatic midfoot OA is the most common presenting condition in this region, affecting 12% of people >50 years of age, 80% of whom report daily pain and disability [53]. Pain in the dorsal central foot region is associated with medial and central midfoot OA with a greater prevalence of disability [59], which requires either weight-bearing radiographs [60] or US imaging assessment to identify joint changes [61]. Midfoot OA presents as an aching pain associated with walking and standing. This can present with osteophytosis and joint narrowing, and MRI studies suggest that bone marrow lesions and tendon signal at the sheath and enthesis can also be associated [62]. Cross-sectional studies suggest that painful midfoot OA can be associated with a flatter foot posture and reduced muscle strength [59, 63].

Midfoot soft tissue pains

Ligament pain in the midfoot usually follows a flexion and rotational sports injury and accounts for a small percentage of visits to emergency departments [64]. These incidents are also known to be associated with high-energy contact injuries, dorsal blunt trauma or higher-energy falls that will often lead to chronic pain and deformity if missed or left untreated [65]. This can present as a persistent dorsal pain aggravated by loading and can overlap with sprain of the ankle or intrinsic foot muscles, but little is known about non-traumatic presentations owing to the complexity of the anatomical structures, poor discernment on foot radiographs and the necessity for MRI investigations for diagnosis [66, 67].

Enthesopathy in the midfoot can be associated with the anterior tibialis, posterior tibialis and peroneus longus tendons, all of which insert within close proximity in the medial arch to support the span of the foot. Studies show that a low degree of tendon effusion and signal at the enthesis can present in healthy non-painful feet, which suggests that this could be a normal variant or a sign of mechanical loading [68, 69]. Enlarged entheses with effusion in multiple locations are found in people with RA and SpA, especially at the peroneus brevis [68, 70, 71]. Tendon enthesopathy can also be a feature of midfoot OA, and this is particularly apparent with the posterior tibialis tendon and peroneus longus tendons, which have insertions into the medial tarsal bones [62].

Pain in the anterior and extensor tendons is often related to acute injury and not commonly reported within sports or running literature [72]. Anecdotally, strains and swelling of these tendons can present in those who adopt an adaptive toe-walking gait style to offload other areas of foot pain or where there is friction with midfoot osteophytosis and footwear. Most of the literature concentrates on the posterior tibialis tendon and flexor longus tendons in dance and sports injuries, which cross the midfoot, and these are described elsewhere [73, 74].

Rearfoot

Rearfoot pain is common. A population-based study of adults demonstrated that one in four cases of foot pain can be attributed to pain in the hindfoot and heel [4]. Common causes of mechanical foot pain for the rearfoot are plantar heel pain, tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction and Achilles tendinopathy.

Plantar heel pain

Plantar heel pain, including plantar fasciitis, plantar fasciopathy, heel pain syndrome and fat pad atrophy [75], affects 4–10% of the population [76] and is more common in people aged >50 years and those who are overweight [76]. Individuals who engage in repetitive weight-bearing activities, such as running [77], or who have occupations that involve standing on hard surfaces for extended periods [78] are at a higher risk of developing plantar heel pain. Plantar heel pain is characterized by pain upon weight-bearing [79] and involves several tissues in the plantar aspect of the heel. However, the insertion of the plantar fascia is considered the main source of the pain for most patients [79].

The diagnosis of plantar heel pain is based on symptoms such as pain and tenderness in the plantar heel, especially after prolonged weight-bearing or when taking the first steps in the morning. During physical assessment, tenderness is elicited upon palpation of the proximal insertion of the plantar fascia at the medial calcaneal tubercle [80]. Radiological assessment is not needed for diagnosis, unless there is diagnostic uncertainty or for surgical planning [81]. Radiography is of limited value because the presence of a calcaneal spur occurs in ~50% of asymptomatic individuals [82]. Musculoskeletal US and MRI are more appropriate when there is diagnostic uncertainty, to help to visualize thickening (>4 mm) of the plantar fascia, a key feature of plantar heel pain [83].

Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction

Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, also known as adult-acquired flatfoot deformity or progressive collapsing foot deformity, is a complex disorder characterized by tibialis posterior weakening and tendinopathy that can be associated with OA changes of the midfoot and hindfoot, and in some cases, this leads to progressive flattening of the midfoot [84, 85]. The prevalence of tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction is unknown, but one study from a general medical clinic in the UK suggested a prevalence of 3% in women aged >40 years of age [86]. It is more common in females, those aged 40–69 years of age and those who are overweight [86, 87].

Key diagnostic features of this condition are pain and swelling along the medial side of the foot, pain with palpation and weakness of the tibialis posterior muscle, difficulty in performing the standing heel raise test (as evidenced by a lack of calcaneal inversion at peak rise, an inability to complete full range of plantarflexion or reduced endurance capacity), and a pronated foot [14, 88–90].

Achilles tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy is characterized by degeneration of the Achilles tendon rather than inflammation and is caused by ineffective tendon repair owing to mechanical loading [91]. As a result, the term tendinopathy is used to describe this condition instead of tendinitis [92]. Achilles tendinopathy affects athletes and sedentary individuals [93–95], males and females equally, and those >35 years of age [94, 96]. The condition adversely impacts health-related quality of life and work productivity [97–99].

People with Achilles tendinopathy report pain and stiffness in the Achilles tendon region, with an insidious onset that is aggravated by loading activities, such as running and jumping [92, 100]. During a physical assessment, patients can experience pain and display weakness with single-leg heel raise and hopping. Palpation of the Achilles tendon can reveal pain and localized nodular thickening [92, 100]. The location of the symptoms can help to differentiate the two subtypes of Achilles tendinopathy: mid-portion and insertional. Mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy occurs when pain occurs 2–6 cm proximal to the calcaneal insertion, whereas insertional Achilles tendinopathy occurs at the calcaneal insertion [92, 100]. In cases where insertional Achilles tendinopathy is present, retrocalcaneal bursitis or Haglund’s deformity may co-exist [92]. Musculoskeletal US and MRI are effective diagnostic tools for identifying Achilles tendinopathy when the diagnosis is uncertain. These modalities provide good to excellent diagnostic accuracy and allow for visualization of pathology of the Achilles tendon and surrounding structures, such as the retrocalcaneal bursa [101]. However, although imaging can help to identify the presence and severity of the condition, studies show a poor relationship between imaging features and pain severity or prognosis [101]; therefore, imaging should be used judiciously.

Foot pain and red flags

A painful, inflamed foot with no open wound can be a diagnostic challenge and often leads to a delay in treatment. Inflammatory arthritis should be considered, especially in the forefoot and toes; gout, SpA and RA are the most common presentations. Charcot neuroarthropathy should be considered in cases of midfoot pain, persistent inflammation and walking difficulties. It presents in middle-aged people with diabetes-related peripheral neuropathy and is more commonly misdiagnosed when associated with alcoholism or undiagnosed sensory loss [102], or dismissed as fragility fractures or progressive flat foot deformity [103]. Early diagnosis and intervention are key to stabilize the foot; otherwise, the resultant ‘rocker bottom’ deformity increases the risk of amputation [104].

Other concerns are highly localized foot pains and inflammation at bone sites, which are more likely to represent a stress response or occult stress fracture in the short tarsal bones and second to fourth metatarsal bones [105]. In cases of new persistent pain with unrelenting or firm swelling in people <40 years of age, space-occupying lesions should also be considered to prevent delays in care [106]. Most presentations are benign, and primary soft tissue and malignant tumours of the foot are rare [106]. Compared with sites above the tibia, sarcomas are less invasive and have a reduced mortality rate, which can be attributed to the size of the structures and interference with function, which can lead to early detection [107]. Metastatic foot lesions (most commonly associated with prostate, bladder and breast cancer) tend to present with severe pain and disability and are more likely to be confused with fragility fractures in the metatarsal bones identifiable on radiographs [108].

Management

Treatment aims to reduce a patient’s symptoms, facilitate healing, promote return to functional activity and prevent re-injury [109]. This can be achieved by managing symptoms, combined with reducing tissue stress of the affected tissue(s) to a tolerable level and improving the ability of the affected tissue(s) to withstand future load/stress [110]. This requires the multifaceted approach described below and, in some cases, multidisciplinary treatment.

Lifestyle and education strategies

Modification of daily activities is important to reduce stress on affected tissues to allow them to heal. Aggravating activities will be unique to each patient but are likely to include occupational activities, caring duties and exercise. It may not always be feasible to avoid or even reduce time spent in these activities. For example, in occupational settings, it may not be possible for an individual not to attend work. In such cases, modification or pacing of activities may be more feasible.

Education, support and referral for weight loss (if appropriate) are important components of management [111]. At present, there are no randomized trials investigating the effectiveness of weight-loss interventions for mechanical foot pain. However, in obese patients with painful foot and ankle arthritis, simulated weight loss to a more normal body mass resulted in a significant improvement in pain [112]. Furthermore, studies of obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery have reported a marked reduction in the prevalence of foot and ankle pain post-operatively [113].

Mechanical strategies

In-shoe foot orthoses, padding and strapping can improve pain by reducing the magnitude of plantar pressure, changing motion of foot joints and reducing tissue stress. Various types of orthotic devices, padding and strapping techniques can be applied for specific purposes, and the interested reader is referred to key texts [114, 115]. The current evidence from randomized trials demonstrates that: for first MTP joint OA, shoe-stiffening inserts are effective for ≤12 months [116], but arch-contouring foot orthoses and cushioning sham showed equal effectiveness [117]; for hallux valgus, arch-contouring foot orthoses are effective at 6 months, but not at 12 months [118]; for midfoot OA, arch-contouring foot orthoses are somewhat effective (in a pilot trial) [119]; for tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, arch-contouring foot orthoses are effective (provided alongside exercise therapy) [120]; and for mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy, arch-contouring foot orthoses are not effective (≤12 months) [121], but in-shoe heel lifts are effective [122].

Education on and consistent use of appropriate footwear is also crucial. In a randomized trial, appropriately fitting footwear significantly improved foot pain and disability in older people with disabling foot pain [123]. Commonly recommended features of appropriate footwear include [124, 125]: sensible style appropriate for activity; appropriate fixation (lace, buckle, velcro); supportive and appropriately fitting (length, width, toe-box shape and depth); shoes that are not excessively worn (upper, midsole and outsole); heel elevation of 5–10 mm; and sole flexion point at the level of the MTP joints and not excessively flexible.

Appropriate pharmacological management

The appropriate use of pharmacological agents can assist the effective management of mechanical foot pain, although specific drug trials are lacking. To ensure the safe and effective use of medication, relevant prescribing guidelines, such as the Therapeutic Guidelines and national evidence-based formularies, need to be consulted [126]. Short-term relief of symptoms can be achieved using paracetamol and NSAIDs [127]. Most cases of mechanical foot pain are superficial, and topical NSAIDs are preferred over oral NSAIDs owing to their better safety profile [128]. For localized mechanical foot pain that is difficult to manage, CS injections can provide short-term pain relief (≤6 weeks) [129–132]. Although IA hyaluronan injections and autologous growth factor injections might be exciting alternative pharmacological approaches for OA and for tendon and plantar fascia pathology, respectively, their effectiveness has not been established in rigorous randomized trials [133–135]. Opioids have limited benefits and significant risks of harm, hence their use is limited to recalcitrant pain, with close monitoring [126].

Therapeutic exercise

Therapeutic strengthening exercises can be used to target the affected muscles and improve the ability of tissue to withstand future stress and strain, reducing the risk of re-injury. The type, intensity and duration of strengthening exercises needs to be individualized. For Achilles tendinopathy, calf muscle eccentric exercises are supported by the strongest evidence [92]. However, targeted strengthening exercises might be effective for other conditions associated with reduced muscle strength, including hallux valgus [136], midfoot OA [63, 137] and tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction [138]. The role of stretching in the treatment of common conditions causing mechanical foot pain, such as plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendinopathy and adult-acquired flat foot, is less clear [92, 139, 140].

Research and future avenues for development

Several clinical and research organizations have highlighted the lack of research into the diagnosis and treatment of musculoskeletal foot pain, particularly when compared with other equally common sites of pain, such as the hand and hip [141–146]. To overcome this, research priorities have been developed, and the top-rated priorities were as follows: the development of robust outcome measures; development of clinical diagnostic criteria; understanding the impact and burden of foot problems; and further investigations into foot pain treatments [141–146].

This review has highlighted the strong relationships between foot pain and increased body mass, in addition to emerging evidence showing the relationship between foot pain and muscle strength. Further research is needed to identify whether fat loss and increased muscle strength will help mechanical foot pain. This would be particularly important to understand in groups with lower leg and foot pains, because this can compound disability [147–149].

Conclusion

Mechanical foot pain includes a large number of pathologies in the forefoot, midfoot and hindfoot. Traditional treatments foot mechanical foot pain are based on reassurance of healing times, pain management, managing the pain through pacing and activity modification, and offering pressure/load management using orthoses and footwear. More research is needed to explore causes and treatments of mechanical foot pain, with particular emphasis on understanding the role of muscle strengthening and weight-loss interventions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge all the researchers and participants whose work we have cited in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jill Halstead, Podiatry Service, Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust, White Rose Office Park, Millshaw Park Lane, Leeds, UK.

Shannon E Munteanu, Discipline of Podiatry, School of Allied Health, Human Services and Sport, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Data availability

There are no new data associated with this article.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Disclosure statement: Both authors declare there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Gates LS, Arden NK, Hannan MT. et al. Prevalence of foot pain across an international consortium of population‐based cohorts. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:661–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garrow AP, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ.. The Cheshire foot pain and disability survey: a population survey assessing prevalence and associations. Pain 2004;110:378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roddy E, Muller S, Thomas E.. Onset and persistence of disabling foot pain in community-dwelling older adults over a 3-year period: a prospective cohort study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2011;66:474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hill CL, Gill T, Menz HB, Taylor AW.. Prevalence and correlates of foot pain in a population-based study: the North West Adelaide health study. J Foot Ankle Res 2008;1:2–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finney A, Dziedzic KS, Lewis M, Healey E.. Multisite peripheral joint pain: a cross-sectional study of prevalence and impact on general health, quality of life, pain intensity and consultation behaviour. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017;18:535–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menz HB, Marshall M, Thomas MJ. et al. Incidence and progression of hallux valgus: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Menz HB, Jordan KP, Roddy E, Croft PR.. Characteristics of primary care consultations for musculoskeletal foot and ankle problems in the UK. Rheumatology 2010;49:1391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menz HB, Jordan KP, Roddy E, Croft PR.. Musculoskeletal foot problems in primary care: what influences older people to consult? Rheumatology 2010;49:2109–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swain S, Sarmanova A, Mallen C. et al. Trends in incidence and prevalence of osteoarthritis in the United Kingdom: findings from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020;28:792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Munro BJ, Steele JR.. Foot-care awareness. A survey of persons aged 65 years and older. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1998;88:242–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marshall M, Blagojevic‐Bucknall M, Rathod‐Mistry T. et al. Identifying long‐term trajectories of foot pain severity and potential prognostic factors: a population‐based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:1123–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkie R, Peat G, Thomas E, Croft P.. The prevalence of person-perceived participation restriction in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1471–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Benvenuti F, Ferrucci L, Guralnik J, Gangemi S, Baroni A.. Foot pain and disability in older persons: an epidemiologic survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:479–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leveille SG, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. et al. Foot pain and disability in older women. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Janwantanakul P, Pensri P, Jiamjarasrangsri V, Sinsongsook T.. Prevalence of self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms among office workers. Occup Med 2008;58:436–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilkie R, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Jordan KP, Pransky G.. Onset of work restriction in employed adults with lower limb joint pain: individual factors and area-level socioeconomic conditions. J Occup Rehabil 2013;23:180–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korda J, Bálint GP.. When to consult the podiatrist. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004;18:587–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Artul S, Habib G.. Ultrasound findings of the painful ankle and foot. J Clin Imaging Sci 2014;4:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Díaz-Mancha J-A, Castillo-López JM, Munuera-Martinez PV. et al. A comparison of fourth-year health sciences students’ knowledge of gross lower and upper limb anatomy: a cross-sectional study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2016;39:450–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuschieri S, Narnaware Y.. Evaluating the knowledge acquisition of lower limb anatomy among medical students during the post‐acute COVID‐19 era. Clin Anat 2023;36:128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nadesalingam K, Ntatsaki E, Hull D, Hughes R.. Musculoskeletal training in rheumatology - what the trainees think. Br J Med Pract 2016;9:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Truntzer J, Lynch A, Kruse D, Prislin M.. Musculoskeletal education: an assessment of the clinical confidence of medical students. Perspect Med Educ 2014;3:238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwieterman B, Haas D, Columber K, Knupp D, Cook C.. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination tests of the ankle/foot complex: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2013;8:416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Coughlin MJ. Common causes of pain in the forefoot in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82:781–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iagnocco A, Coari G, Palombi G, Valesini G.. Sonography in the study of metatarsalgia. J Rheumatol 2001;28:1338–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Munteanu SE, Auhl M, Tan JM. et al. Characterisation of first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis using magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:5067–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Menz HB, Roddy E, Marshall M. et al. Demographic and clinical factors associated with radiographic severity of first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: cross-sectional findings from the Clinical Assessment Study of the Foot. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vanore JV, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR. et al. ; Clinical Practice Guideline First Metatarasophalangeal Joint Disorders Panel of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. Diagnosis and treatment of first metatarsophalangeal joint disorders. Section 2: hallux rigidus. J Foot Ankle Surg 2003;42:124–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zammit GV, Munteanu SE, Menz HB.. Development of a diagnostic rule for identifying radiographic osteoarthritis in people with first metatarsophalangeal joint pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:939–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management, NICE guideline NG226, London, UK, 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng226 (4 June 2023, date last accessed). [PubMed]

- 31. Vanore JV, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR. et al. ; Clinical Practice Guideline First Metatarsophalangeal Joint Disorders Panel of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. Diagnosis and treatment of first metatarsophalangeal joint disorders. Section 1: hallux valgus. J Foot Ankle Surg 2003;42:112–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nix S, Smith M, Vicenzino B.. Prevalence of hallux valgus in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 2010;3:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Menz HB, Roddy E, Thomas E, Croft PR.. Impact of hallux valgus severity on general and foot‐specific health‐related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hurn SE, Vicenzino B, Smith MD.. Functional impairments characterizing mild, moderate, and severe hallux valgus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Menz HB, Morris ME, Lord SR.. Foot and ankle risk factors for falls in older people: a prospective study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2006;61:866–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mickle KJ, Munro BJ, Lord SR, Menz HB, Steele JR.. ISB Clinical Biomechanics Award 2009: toe weakness and deformity increase the risk of falls in older people. Clin Biomech 2009;24:787–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garrow AP, Papageorgiou A, Silman AJ. et al. The grading of hallux valgus: the Manchester Scale. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2001;91:74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hardy RH, Clapham JCR.. Observations on hallux valgus; based on a controlled series. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1951;33-B:376–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Piggott H. The natural history of hallux valgus in adolescence and early adult life. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1960;42-B:749–60. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hooper L, Bowen CJ, Gates L. et al. Comparative distribution of ultrasound‐detectable forefoot bursae in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:869–77. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Larsen SB, Søgaard SB, Nielsen MB, Torp-Pedersen ST.. Diagnostic considerations of intermetatarsal bursitis: a systematic review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023;13:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gregg J, Marks P.. Metatarsalgia: an ultrasound perspective. Australas Radiol 2007;51:493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ganguly A, Warner J, Aniq H.. Central metatarsalgia and walking on pebbles: beyond Morton neuroma. Am J Roentgenol 2018;210:821–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gerard VY, Judge MS, Hudson JR, Seidelmann FE.. Predislocation syndrome: progressive subluxation/dislocation of the lesser metatarsophalangeal joint. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92:182–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Taylor AJ, Menz HB, Keenan A-M.. The influence of walking speed on plantar pressure measurements using the two-step gait initiation protocol. Foot 2004;14:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Greisberg J, Sperber L, Prince DE.. Mobility of the first ray in various foot disorders. Foot Ankle Int 2012;33:44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nyska M, Liberson A, McCabe C, Linge K, Klenerman L.. Plantar foot pressure distribution in patients with hallux valgus treated by distal soft tissue procedure and proximal metatarsal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Surg 1998;4:35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mak M, Chowdhury R, Johnson R.. Morton's neuroma: review of anatomy, pathomechanism, and imaging. Clin Radiol 2021;76:235.e15–235.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weinfeld SB, Myerson MS.. Interdigital neuritis: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1996;4:328–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Latinovic R, Gulliford M, Hughes R.. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:263–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mahadevan D, Venkatesan M, Bhatt R, Bhatia M.. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for Morton's neuroma compared with ultrasonography. J Foot Ankle Surg 2015;54:549–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bignotti B, Signori A, Sormani MP. et al. Ultrasound versus magnetic resonance imaging for Morton neuroma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 2015;25:2254–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thomas MJ, Peat G, Rathod T. et al. The epidemiology of symptomatic midfoot osteoarthritis in community-dwelling older adults: cross-sectional findings from the Clinical Assessment Study of the Foot. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Redmond A, Crane Y, Menz H.. Normative values for the Foot Posture Index. J Foot Ankle Res 2008;1:6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rao S, Baumhauer J, Nawoczenski D.. Is barefoot regional plantar loading related to self-reported foot pain in patients with midfoot osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:1019–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chiou W-K, Chiu H-T, Chao A-S, Wang M-H, Chen Y-L.. The influence of body mass on foot dimensions during pregnancy. Appl Ergon 2015;46(Pt A):212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Karadag-Saygi E, Unlu-Ozkan F, Basgul A.. Plantar pressure and foot pain in the last trimester of pregnancy. Foot Ankle Int 2010;31:153–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Walsh TP, Butterworth PA, Urquhart DM. et al. Increase in body weight over a two-year period is associated with an increase in midfoot pressure and foot pain. J Foot Ankle Res 2017;10:31–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Arnold J, Marshall M, Thomas M. et al. Midfoot osteoarthritis: potential phenotypes and their associations with demographic, symptomatic and clinical characteristics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Menz HB, Munteanu SE, Marshall M. et al. Identification of radiographic foot osteoarthritis: sensitivity of views and features using the La Trobe radiographic atlas. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2022;74:1369–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Camerer M, Ehrenstein B, Hoffstetter P, Fleck M, Hartung W.. High-resolution ultrasound of the midfoot: sonography is more sensitive than conventional radiography in detection of osteophytes and erosions in inflammatory and non-inflammatory joint disease. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:2145–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Arnold JB, Halstead J, Martín‐Hervás C. et al. Bone marrow lesions and magnetic resonance imaging–detected structural abnormalities in patients with midfoot pain and osteoarthritis: a cross‐sectional study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:1113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Arnold JB, Halstead J, Grainger AJ. et al. Foot and leg muscle weakness in people with midfoot osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nunley JA, Vertullo CJ.. Classification, investigation, and management of midfoot sprains: Lisfranc injuries in the athlete. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:871–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE.. Orthopedic pitfalls in the ED: Lisfranc fracture-dislocation. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19:71–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Koetser IC, Hernández EAE, Kerkhoffs GM. et al. Don't miss me: midfoot sprains, a point-of-care review. Semen Musculoskelet Radiol 2023;27:245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carter TH, Heinz N, Duckworth AD, White TO, Amin AK.. Management of Lisfranc injuries: a critical analysis review. JBJS Rev 2023;11:e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ward IM, Kissin E, Kaeley G. et al. Ultrasound features of the posterior tibialis tendon and peroneus brevis tendon entheses: comparison study between healthy adults and those with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017;69:1519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Benjamin M, Toumi H, Ralphs JR. et al. Where tendons and ligaments meet bone: attachment sites (‘entheses’) in relation to exercise and/or mechanical load. J Anat 2006;208:471–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kaeley GS. Review of the use of ultrasound for the diagnosis and monitoring of enthesitis in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:338–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Balint P, Kane D, Wilson H, McInnes I, Sturrock R.. Ultrasonography of entheseal insertions in the lower limb in spondyloarthropathy. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:905–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yao W, Zhang Y, Zhang L. et al. MRI features of and factors related to ankle injuries in asymptomatic amateur marathon runners. Skeletal Radiol 2021;50:87–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chhabra A, Soldatos T, Chalian M. et al. 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with relevance to clinical staging. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011;50:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hillier J, Peace K, Hulme A, Healy J.. MRI features of foot and ankle injuries in ballet dancers. British J Radiol 2004;77:532–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hossain M, Makwana N.. “Not Plantar Fasciitis”: the differential diagnosis and management of heel pain syndrome. Orthopaedics Trauma 2011;25:198–206. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Thomas MJ, Whittle R, Menz HB. et al. Plantar heel pain in middle-aged and older adults: population prevalence, associations with health status and lifestyle factors, and frequency of healthcare use. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:337–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lopes AD, Hespanhol LC, Yeung SS, Costa LOP.. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A systematic review. Sports Med 2012;42:891–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Werner RA, Gell N, Hartigan A, Wiggerman N, Keyserling WM.. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis among assembly plant workers. PM R 2010;2:110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR. et al. ; American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons Heel Pain Committee. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline–revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49:S1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Enseki K, Harris-Hayes M, White DM. et al. ; Orthopaedic Section of the American Physical Therapy Association. Nonarthritic hip joint pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014;44:A1–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Martin RL, Davenport TE, Reischl SF. et al. ; American Physical Therapy Association. Heel pain—plantar fasciitis: revision 2014. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2014;44:A1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Osborne H, Breidahl W, Allison G.. Critical differences in lateral X-rays with and without a diagnosis of plantar fasciitis. J Sci Med Sport 2006;9:231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McMillan AM, Landorf KB, Barrett JT, Menz HB, Bird AR.. Diagnostic imaging for chronic plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Foot Ankle Res 2009;2:32–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Myerson MS, Thordarson DB, Johnson JE. et al. Classification and nomenclature: progressive collapsing foot deformity. Foot Ankle Int 2020;41:1271–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rhim HC, Dhawan R, Gureck AE. et al. Characteristics and future direction of tibialis posterior tendinopathy research: a scoping review. Medicina 2022;58:1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Woods B, Angel JC, Singh D.. The prevalence of symptomatic posterior tibialis tendon dysfunction in women over the age of 40 in England. Foot Ankle Surg 2009;15:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chung H-W, Kim J-I, Lee H-D, Suh J-S.. Body mass index in patients with early posterior tibial tendon dysfunction in Korea. J Kor Orthopaed Assoc 2010;45:301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Johnson KA, Strom DE.. Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;239:196–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Angel JC, Singh D. et al. Tibialis posterior dysfunction: a common and treatable cause of adult acquired flatfoot. BMJ 2004;329:1328–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Myerson M. Adult acquired flatfoot deformity: treatment of dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon. Instr Course Lect 1997;46:393–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Movin T, Gad A, Reinholt FP, Rolf C.. Tendon pathology in long-standing achillodynia: biopsy findings in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 1997;68:170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Martin RL, Chimenti R, Cuddeford T. et al. Achilles pain, stiffness, and muscle power deficits: midportion Achilles tendinopathy revision 2018. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018;48:A1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kujala UM, Sarna S, Kaprio J.. Cumulative incidence of Achilles tendon rupture and tendinopathy in male former elite athletes. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15:133–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. de Jonge S, Van den Berg C, de Vos R-J. et al. Incidence of midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the general population. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:1026–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hootman J, Macera C, Ainsworth B. et al. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among sedentary and physically active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt P.. Acute and overuse injuries correlated to hours of training in master running athletes. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Sleeswijk Visser TSO, van der Vlist AC, van Oosterom RF. et al. Impact of chronic Achilles tendinopathy on health-related quality of life, work performance, healthcare utilisation and costs. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2021;7:e001023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Turner J, Malliaras P, Goulis J, Mc Auliffe S.. “It's disappointing and it's pretty frustrating, because it feels like it's something that will never go away.” A qualitative study exploring individuals’ beliefs and experiences of Achilles tendinopathy. PLoS One 2020;15:e0233459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ceravolo ML, Gaida JE, Keegan RJ.. Quality-of-life in Achilles tendinopathy: an exploratory study. Clin J Sport Med 2020;30:495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Matthews W, Ellis R, Furness J, Hing WA.. The clinical diagnosis of Achilles tendinopathy: a scoping review. PeerJ 2021;9:e12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Docking SI, Ooi CC, Connell D.. Tendinopathy: is imaging telling us the entire story? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015;45:842–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Arapostathi C, Tentolouris N, Jude EB.. Charcot foot associated with chronic alcohol abuse. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2012008263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Bukata SV, Digiovanni BF, Friedman SM. et al. A guide to improving the care of patients with fragility fractures. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2011;2:5–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Strotman PK, Reif TJ, Pinzur MS.. Charcot arthropathy of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2016;37:1255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Weishaupt D, Schweitzer ME.. MR imaging of the foot and ankle: patterns of bone marrow signal abnormalities. Eur Radiol 2002;12:416–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Ashman CJ, Klecker RJ, Yu JS.. Forefoot pain involving the metatarsal region: differential diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiographics 2001;21:1425–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Zeytoonjian T, Mankin HJ, Gebhardt MC, Hornicek FJ.. Distal lower extremity sarcomas: frequency of occurrence and patient survival rate. Foot Ankle Int 2004;25:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Bakotic B, Huvos AG.. Tumors of the bones of the feet: the clinicopathologic features of 150 cases. J Foot Ankle Surg 2001;40:277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Munteanu S. Achilles tendon. In: Rome K, McNair P, eds. Management of chronic musculoskeletal conditions in the foot and lower leg. London, UK: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014: 145–79. [Google Scholar]

- 110. McPoil TG, Hunt GC.. Evaluation and management of foot and ankle disorders: present problems and future directions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1995;21:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults. London UK, 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph53/ (4 June 2023, date last accessed).

- 112. Morley WJ, Dawe E, Boyd R. et al. ; Royal Bournemouth and Christchurch Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust UK. Simulated weight reduction using an anti-gravity treadmill – a pilot study of the impact of weight loss on foot and ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Surg 2021;27:809–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. McGoey BV, Deitel M, Saplys RJ, Kliman ME.. Effect of weight loss on musculoskeletal pain in the morbidly obese. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72:322–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Menz HB. Orthotic therapy. In: MenzHB, ed. Foot problems in older people. Assessment and management. Edinburgh, New York: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008: 217–34. [Google Scholar]

- 115. Landorf K, Cotchett M, Bonano D.. Foot orthoses. In: Burrow J, Rome K, Padhiar N, eds. Neale’s disorders of the foot and ankle, 9th edn. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2020: 555–75. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Munteanu S, Landorf K, McClelland J. et al. Shoe-stiffening inserts for first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2021;29:480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Paterson KL, Hinman RS, Metcalf BR. et al. Effect of foot orthoses vs sham insoles on first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis symptoms: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:956–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Torkki M, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S. et al. Surgery vs orthosis vs watchful waiting for hallux valgus: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2001;285:2474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Halstead J, Chapman GJ, Gray JC. et al. Foot orthoses in the treatment of symptomatic midfoot osteoarthritis using clinical and biomechanical outcomes: a randomised feasibility study. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:987–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Yurt Y, Şener G, Yakut Y.. The effect of different foot orthoses on pain and health related quality of life in painful flexible flat foot: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019;55:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Munteanu SE, Scott LA, Bonanno DR. et al. Effectiveness of customised foot orthoses for Achilles tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:989–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Rabusin CL, Menz HB, McClelland JA. et al. Efficacy of heel lifts versus calf muscle eccentric exercise for mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy (HEALTHY): a randomised trial. Br J Sports Med 2021;55:486–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Menz HB, Auhl M, Ristevski S, Frescos N, Munteanu SE.. Effectiveness of off-the-shelf, extra-depth footwear in reducing foot pain in older people: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70:511–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Menz HB. Footwear considerations. In: Menz HB, ed. Foot problems in older people: assessment and management. Edinburgh, New York: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008: 235–50. [Google Scholar]

- 125. Williams A. Footwear. In: Burrow J, Rome K, Padhiar N, eds. Neale's disorders of the foot and ankle, 9th edn. Elsevier, 2020: 520–54. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Expert group for Rheumatology guidelines. Theraputic Guidelines: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2021. https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au/guideLine?guidelinePage=Rheumatology&frompage=etgcomplete (4 June 2023, date last accessed).

- 127. Freo U, Ruocco C, Valerio A, Scagnol I, Nisoli E.. Paracetamol: a review of guideline recommendations. J Clin Med 2021;10:3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Derry S, Moore RA, Gaskell H, McIntyre M, Wiffen PJ.. Topical NSAIDs for acute musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD007402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Uson J, Rodriguez-García SC, Castellanos-Moreira R. et al. EULAR recommendations for intra-articular therapies. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Whittaker GA, Munteanu SE, Menz HB. et al. Corticosteroid injection for plantar heel pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B.. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2010;376:1751–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Lim PQX, Lithgow MJ, Kaminski MR. et al. Efficacy of non-surgical interventions for midfoot osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 2023;43:1409–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Munteanu SE, Zammit GV, Menz HB. et al. Effectiveness of intra-articular hyaluronan (Synvisc, hylan GF 20) for the treatment of first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1838–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Bell KJ, Fulcher ML, Rowlands DS, Kerse N.. Impact of autologous blood injections in treatment of mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy: double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;346:f2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Kearney RS, Ji C, Warwick J, ATM Trial Collaborators et al. Effect of platelet-rich plasma injection vs sham injection on tendon dysfunction in patients with chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;326:137–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Mickle KJ, Caputi P, Potter JM, Steele JR.. Efficacy of a progressive resistance exercise program to increase toe flexor strength in older people. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2016;40:14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Gong Q, Halstead J, Keenan AM. et al. Intrinsic foot muscle size and associations with strength, pain and foot-related disability in people with midfoot osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2023;101:105865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Ross MH, Smith MD, Mellor R, Vicenzino B.. Exercise for posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials and clinical guidelines. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2018;4:e000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Salvioli S, Guidi M, Marcotulli G.. The effectiveness of conservative, non-pharmacological treatment, of plantar heel pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Foot (Edinb) 2017;33:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Kulig K, Reischl S, Pomrantz A. et al. Nonsurgical management of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with orthoses and resistive exercise: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2009;89:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Arnold JB, Bowen CJ, Chapman LS. et al. ; International Foot and Ankle Osteoarthritis Consortium. International Foot and Ankle Osteoarthritis Consortium review and research agenda for diagnosis, epidemiology, burden, outcome assessment and treatment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:945–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Digiovanni C, Banerjee R, Villareal R.. Foot and ankle research priority 2005: report from the Research Council of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:133–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Saltzman CL, Domsic RT, Baumhauer JF. et al. Foot and ankle research priority: report from the Research Council of the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society. Foot Ankle Int 1997;18:447–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Mangwani J, Hau M, Thomson L.. Research priorities in foot and ankle conditions: results of a UK priority setting partnership with the James Lind Alliance. BMJ Open 2023;13:e070641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Posmyk L, Carter-Wale RL, Clark K. et al. Research priority setting in UK podiatric surgery. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research 2023;16:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Graham A. Foot health research priorities: James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership 2019. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/foot-health/ (4 June 2023, date last accessed).

- 147. Raja R, Dube B, Hensor EM. et al. The clinical characteristics of older people with chronic multiple-site joint pains and their utilisation of therapeutic interventions: data from a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Keenan AM, Drake C, Conaghan PG, Tennant A.. The prevalence and impact of self-reported foot and ankle pain in the over 55 age group: a secondary data analysis from a large community sample. J Foot Ankle Res 2019;12:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Keenan AM, Tennant A, Fear J. et al. Impact of multiple joint problems on daily living tasks in people in the community over age fifty-five. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no new data associated with this article.