Abstract

Purpose:

Identification of children with specific language impairment (SLI) can be difficult even though their language can lag that of age peers throughout childhood. A clinical grammar marker featuring tense marking in simple clauses is valid and reliable for young children but is limited by ceiling effects around the age of 8 years. This study evaluated a new, more grammatically challenging complex sentence task in children affected or unaffected with SLI in longitudinal data, ages 5–18 years.

Method:

Four hundred eighty-three children (213 unaffected, 270 affected) between 5 and 18 years of age participated, following a rolling recruitment longitudinal design encompassing a total of 4,148 observations. The new experimental grammaticality judgment task followed linguistic concepts of syntactic sites for finiteness and movement within complex clauses. Growth modeling methods evaluated group differences over time for four different outcomes; three were hypothesized to evaluate optional omissions of overt finiteness forms in authorized sentence sites, and one evaluated an overt error of tense marking.

Results:

As in earlier studies of younger children, growth models for the SLI group were consistently lower than the unaffected group, although the growth trajectories across groups did not differ. The results replicated across four item types defined by omissions with minor differences for an item with an overt error of tense marking. Covariates of child nonverbal IQ, mother's education, and child sex did not significantly moderate these effects.

Conclusion:

The outcomes support the task as having potential screening value for identification of children with SLI and are consistent with linguistic interpretations of task demands.

Young children acquire language without apparent effort or explicit tutoring around the world and across diverse languages and cultures. However, for unknown reasons, 7%–10% of children fall behind their age peers in ease of language acquisition (Norbury et al., 2016; Tomblin et al., 1997). In search of a better understanding of how some children struggle to acquire what comes easily to others, this study focuses on how children with specific language impairment (SLI) acquire language across the age span of 5–18 years. These children have no hearing loss or other developmental delays, yet they have delayed and incomplete mastery of language. A preschool child with SLI often has a history of being a late talker (reaching language milestones later than peers) and is likely to make frequent grammatical errors when speaking. With increasing age, the condition of SLI is likely to persist (i.e., children with SLI are not likely to “catch up” to their age peers; Norbury et al., 2017; Rice, 2012; Rice & Hoffman, 2015; Rice et al., 2009; Tomblin & Nippold, 2014b). The underlying linguistic limitations may become more hidden with age, as an adolescent with SLI might avoid complex sentences in conversations and spontaneous language samples, obscuring their underlying grammatical limitations (Tomblin & Nippold, 2014a). As a result, an unknown number of children with SLI remain unidentified and out of reach of clinical services. An effective screener for children with SLI throughout childhood is needed as a first step toward the provision of clinical services for missed cases in older children and adolescents.

Key properties of the grammar of young children with SLI are known to pose long-standing difficulties in acquisition, relative to their age peers, as reported in the longitudinal studies of children with SLI from 3 to 12 years of age, reviewed below. These key properties have not been explicitly studied in adolescence in ways that link to the research with younger children, a gap that should be addressed to learn more about the subsequent years of “avoiding complex sentences in conversations” by those with SLI.

The present longitudinal study aims to fill the empirical and interpretive gap by focusing on linguistic models of simple clause structure that have identified some of the grammatical elements known to appear late in acquisition for children with SLI. Here, to extend our studies of children's developmental growth into elementary and secondary school, we focus on possible links of early grammar errors with related elements of complex clauses. Our hypothesis is that underlying linguistic properties, such as finiteness marking, that pose challenges for young typically developing children and persist in children with SLI shift their manifestation from simple to complex clauses as children age. The question is whether earlier weakness in finiteness marking lingers as children must master complex sentences. If so, such continued weakness would be useful for identifying children with SLI.

Finiteness Marking as a Morphosyntactic Linguistic Property of English That Shows Errors Across Grammatical Forms for Typical Young English-Speaking Children

Morphosyntax of Finiteness in English Grammar

As suggested by the meaning of finite (i.e., having definite or definable limits), finite verbs are defined by sentential context as “a verb form that can function as a predicate or as the initial element (or ‘head’) of one and that is limited (or ‘constrained’) (as in tense, person, and number)” (Merriam-Webster online dictionary, April 12, 2023). Languages vary in the ways finiteness appears. In English, finite verbs carry number and person marking to align with the number and person of the subject and also carry tense marking (present, past; Cowper, 2009; Guasti, 2016; Quirk et al., 1985). Thus, the location/site of a finite verb is determined by the sentence structure in a morphosyntactic relationship. The surface form of the person, number, and tense marking is determined by morphophonological rules. Finally, English usually has one finite verb at the head of each clause, although they can appear in dependent and independent clauses.

Consider the following examples of finiteness marking in English, where underlining indicates the finiteness marking site (the verbal head of the clause), an asterisk indicates a morphophonological overregularization, and double asterisks indicate an ungrammatical sentence structure. The verbal head of sentence is identified as the verb that carries person/number agreement or past tense marking. Note that all the examples follow the rule that only one finiteness-marked verb can appear as the head of the clause. Items 1 and 7 demonstrate that auxiliary BE is occupies the finiteness site in these sentences, as we can see in comparison to Item 5, where auxiliary BE is shifts from present to past tense was. Items 2 and 3 show that lexical (content/open class) verbs also show morphophonological changes to indicate the verbal head of the clause. Note that, in Item 4, the past tense form of break shows morphophonological error in an overregularization of past tense formation. However, the verb is where it belongs in the syntactic location as the verbal head of the sentence, indicating speaker awareness of the finiteness requirement although the phonological formation is inaccurate. This variation from the expected “broke” is usually scored as an “incorrect” attempt at past tense in speech or language assessments. Here, such morphosyntactic overregularizations are considered as evidence of past tense/finiteness knowledge (following the scoring of the Test of Early Grammatical Impairment [TEGI] for younger children), which counts morphophonological errors of past tense (as in Item 4) as evidence of attempted finiteness marking (Rice & Wexler, 2001). Prior research shows longitudinal growth differences between children with SLI and children with lower nonverbal cognitive levels according to verb form (regular vs. irregular morphophonology; overregularized vs. correct forms of irregular past tense; Rice et al., 2004).

The vase is broken.

The dog broke the vase.

The dog breaks the vase.

The dog *breaked the vase.

The vase was broken by the dog.

The vase was *breaked by the dog.

Is the vase broken?

**Breaks the dog the vase?

Why did the dog break it?

**Does the boy his homework?

Items 1–6 are simple clauses with a single main verb in canonical subject–verb order referring to a simple scene of a broken vase caused by a dog. Item 7 shows how the word order adjusts to form a question: The finiteness marking site “raises” to precede the subject, in contrast to Item 1, demonstrating that auxiliary BE can raise in questions, as can copula BE. In contrast, lexical verbs cannot, as shown in Item 8. Instead, as shown in Item 9, auxiliary DO is inserted in the finiteness marking site (Pollock, 1989). Note that DO can be used as either an auxiliary or main verb and children use the form frequently across both grammatical categories, although they avoid errors such as Item 10, indicating knowledge of the underlying morphosyntactic rules. Even children with SLI avoid errors of confusing main verb DO and auxiliary DO (Rice & Blossom, 2013).

Moving on to conjoined clause sentences, Items 11–13 are shown below. Item 11 shows that finiteness marking appears in each clause in conjoined clause sentences, indicating how the number of finiteness marking slots per sentence depends on the sentence structure. It is not the number of verb forms that count; it is the number of finiteness marking sites, as indicated by the rules for heads of clauses. Although Item 12 is a longer sentence, only one finiteness marking slot appears, “planned,” whereas two verb forms (“feed” and “wash”) follow infinitival “to” and are not marked for finiteness and a third verb form, “eating,” is a nonfinite gerund. Item 13 is a complex sentence formed with a full propositional complement clause (i.e., a subordinate clause that serves to complete the meaning of a noun or verb in a sentence). In this example, the verb “say” (Levin, 1993) has a complement clause that serves as a direct object, (i.e., “he enjoyed reading”). The verb “say” shares this property with other verbs such as “believe,” “tell,” “know,” and “understand.” The complementizer “that” may or may not introduce the subordinate clause.

11. The dog wants to break the vase because it is fun.

12. He planned to feed the dog and wash the cat before eating lunch.

13. John said that he enjoyed reading.

Young English-Speaking Typically Developing Children Are Likely to Omit Required Finiteness Forms, Including Auxiliary BE and DO, Copula BE, Past Tense, and Third-Person Singular –s

Beginning with the seminal study of Roger Brown (Brown, 1973) and his notion of “obligatory contexts” for morphology, and many subsequent textbooks, it is well known that young English learners pass through early stages in which they are likely to omit copula or auxiliary forms of BE (Items 1, 5, and 6), copula BE (Items 7 and 9), auxiliary DO (Item 8; although this morpheme was not included in Brown's study but in later studies), third-person singular subject–verb agreement (Item 9) or past tense on lexical verbs (Items 2 and 3) in the sites where the forms are required or “obligatory.” Irregular past tense verbs, such as “broke,” can appear as the base form (i.e., “break,” with omitted past tense morphophonology on the lexical verb, and later as overregularized errors such as “breaked”; Redmond & Rice, 2001; Rice et al., 2000).

Optional Infinitive Theory of Finiteness Omissions in Typically Developing Children and Children With SLI

Linguistic scholars have recognized finiteness marking as a common underlying property of “is” and auxiliary “do” and past tense affixes such as –d, which are described in traditional grammars (Quirk et al., 1985). Generative grammar theorists proposed interpretations of the pattern of errors and strengths in young children's language, such as the Optional Infinitive Account of young children's early errors in grammar (Wexler, 1994, 2003). This theory drew upon earlier analyses of multiple languages, including the ways in which the auxiliary DO in English shares syntactic properties with past tense and subject–verb agreement morphology in English and other languages (Guasti, 2016; Poeppel & Wexler, 1993; Pollock, 1989). Some languages reveal underlying relationships between word order and morphological rules more obviously than in English. For example, German is a V2 language, defined by having the finite verb (i.e., one conjugated to match the subject) in the second position of a sentence. In her textbook, Teresa Guasti (Guasti, 2016) provides a clear description of how the expected distributional pattern linking finiteness and word order appears in the utterances of young children acquiring German or other similar languages. The adultlike distributions of finite verbs in the second position and final position reserved for infinitives is evident in children's utterances as early as when they begin to produce three-word utterances. At the same time, children learning languages with this contingency between finiteness and syntax also occasionally produce main clauses containing an infinitival verb, rather than a finite one, and the infinitive form appears at the end of the clause. This phenomenon, referred to as “root infinitives” or “optional infinitives” (Poeppel & Wexler, 1993), is a variant of the adult grammar hypothesized to reflect incomplete maturation of relevant grammatical principles (Rizzi, 1993; Wexler, 1999). The “root infinitive” pattern is also evident in young German-speaking children with SLI, with more time needed to acquire the rules for finiteness marking (Rice et al., 1997).

Thus, studies of young children's acquisition of non-English languages led to new insights about the underlying linguistic properties of morphosyntax that were vulnerable to omission in children's sentences. Examples 1–10 above illustrate sentences possibly used by young English-speaking children. Predominant errors are omission of copula and auxiliary BE, auxiliary DO, past tense (regular or irregular), and third-person –s person/number marking. In Examples 1 and 7, “is” could be omitted; in Example 3, third-person singular –s is likely to be omitted; in Example 2, “break” is likely to be used instead of “broke”; Examples 5 and 6 are likely to show omitted “was.” In Example 9, “did” is likely to be omitted (Rice & Wexler, 1996, 2001; Rice et al., 1998, 1999, 2000).

Although young English-speaking typically developing children are likely to omit the required finiteness morphemes, when the morphemes appear they are likely to be used in the correct location in a sentence, with the correct form, a period described as “optional infinitive” use (Wexler, 1994). Morphosyntactic errors of word order, such as those shown in Items 8 and 10, are rare, even in young children, indicating that, early on, English-speaking children are guided by the underlying abstract grammar. It is as if the children assume “maybe or maybe not” for required overt morphemes in the syntactic positions requiring finiteness marking.

Extended Optional Infinitives as a Grammar Marker of SLI

Patterns predicted by an “extended optional infinitive period” (i.e., omissions of finiteness marking in obligatory contexts) are well documented as a marker/identifier of SLI in children ages 3–9 years. At this relatively early stage of children's development, studies have measured finiteness as omitted tense and agreement morphemes in obligatory contexts in English single-clause declarative sentences and single-clause questions (Rice & Wexler, 2001; Tager-Flusberg & Cooper, 1999), such as Items 1–10 above. A screening test for finiteness impairments was developed for children up to 9 years of age (Rice & Wexler, 2001). A modified version with an age range that extends from 4 through 21 years is now available as a free app at Apple, Grammaggio.

A series of longitudinal studies has documented that children with SLI start later than their age peers in acquisition of finiteness markers, as evident in single-clause declarative sentence elicitation tasks (Rice & Wexler, 1996; Rice et al., 1995, 1998, 2000) and in grammaticality judgment tasks with single-clause questions with omitted tense and agreement morphemes (Rice et al., 1999). Subsequent studies of twin children ages 4 and 6 years report moderately high heritability for poor performance on finiteness tasks in the full sample of children (Rice et al., 2018) and significant heritability of finiteness marking of SLI in the twin sample at ages 4 and 6 years (Rice et al., 2020). Furthermore, significant heritability was reported for a sample of 16-year-old children for a grammaticality judgment task of omitted finiteness markers in single-clause sentences (Dale et al., 2018). Although of high interest for possible causal mechanisms involved in mastery of finiteness marking, caution is warranted for direct comparisons of young twin data with singleton data due to replicated evidence of increased risk for late language acquisition for twins compared to singletons (Taylor et al., 2018; Zubrick et al., 2007).

Gaps in Knowledge of Finiteness Marking for Children With SLI, Ages 9–18 Years

The gap in knowledge of interest here is: What happens with finiteness marking in complex sentences that are linguistically related to the tasks used to document late grammatical acquisition of young typically developing children and somewhat older children with SLI? Although the omission of finiteness markers in single-clause tasks appears to be detected and avoided by most single-born children with SLI by 9 years of age, does this mean that this grammar feature is also mastered in complex sentences? Or does the earlier weakness in finiteness marking linger as children must master complex sentences?

Experimental Studies of Complex Sentences of Children With SLI

Multiple methods support the conclusion that complex sentences are candidates for clinical markers of children with SLI. Previous studies of complex sentences in children with SLI used standardized assessment tasks to measure the ability to follow spoken directions involving complex syntax and accuracy in repeating long and complex sentences (Johnson et al., 1999), or analyses of spoken discourse (Tomblin & Nippold, 2014a). Other studies used experimental tasks focusing on various sentence contexts to investigate possible group effects, predicting that children with SLI would perform lower in accuracy or differently in brain processing than typically developing children. Experimental linguistic tasks have included argument structure complexity for use of auxiliary BE forms by children with SLI ages 4;2 to 6;7 (years;months; Grela & Leonard, 2000); comprehension of nonlocal dependencies in passive, pronominal, or reflexive sentences in children between the ages of 6 and 12 years (Montgomery & Evans, 2009; Montgomery et al., 2021); relative clause constructions in sentence recall tasks in SLI children with a mean age of 6;10, an age control group, and another control group with a mean age of 4;9 (Frizelle & Fletcher, 2014); and grammaticality judgments of long-distance dependencies by children ages 7–12 years in sentences such as “He makes the quiet boy talks a little louder” in an ERP study (Purdy et al., 2014). The results of these studies supported the conclusion that complex sentences could be clinical markers for children with SLI, as well as the broader generalization that complex sentences could be difficult for children with SLI into adolescence. One study reported training outcomes using adverbial clauses, object complements, and relative clauses in children diagnosed as SLI, ages 10;0–14;11 (Balthazar & Scott, 2018). Target sentences included three categories, one of which was two object complement clauses, such as “The Queen of Spain learned that Columbus has reached the New World” (finite complement with “has”) and “Jake volunteered to work the difficult math problem on the blackboard” (nonfinite infinitival “to”). Object complement clauses were the most difficult category for the children with SLI to learn. Although the authors did not discuss further why this type of sentence was most difficult, it could be related to their finiteness requirements or to other linguistic demands. Common interpretive themes across the articles posit possible limitations in cognitive demands for the older SLI children as factors contributing to poor performance, such as attention, verbal memory, and verbal meanings/conceptual content.

Limitations of Previous Studies Addressed by This Study

The topic of finiteness marking in complex sentences has not been the focus of study in SLI children over 12 years of age, and our literature review did not find previous longitudinal studies focusing on the morphosyntactic properties of tense and agreement marking in complex sentences. The present longitudinal study was designed to fill the empirical void between 9 years and adulthood in affected and unaffected children's understanding of tense and agreement markers. It does so by identifying well-specified complex question structures that are theoretically related to the single-question clauses judged by younger children. We then used these question structures to generate experimental tasks for longitudinally assessing children's performance on variations of possible errors to determine if the outcomes parallel those of younger children.

Complex Sentences for Finiteness Marking Grammaticality Judgment Tasks

As noted in the earlier Item 13 sentence, the verb “say” can appear in complex sentences with a complement clause that serves as a direct object. Consider the linguistic relations evident in this set of sentences, where parentheses indicate possible omissions:

14. Mary say(s) something.

15. When (did) Mary say something?

16. She paint(ed) a door yesterday.

17. When (did) Mary say she paint(ed) a door?

Finiteness marking, indicated by underlining in the four sentences, appears in one syntactic location in each of the simple clauses (Items 14–16) and twice in the complex clause (Item 17). Different morphological forms appear in Item 17: did, say, and –ed. Note that in the complex question, Item 17, there are two finiteness marking positions for three verbs: One is the initial did as an auxiliary verb inserted prior to the subject that blocks finiteness on the following second verb, say. The third verb, painted, is in the second finiteness marking site. In the complex question of Item 17, finiteness no longer appears on the lexical verb say following the subject Mary because the finiteness position shifts to precede the subject. This position is filled by auxiliary DO, which now carries past tense or subject–verb agreement morphology to meet the finiteness requirement of the question, as also shown in Item 15. Children must learn these distributional requirements for English finiteness marking. Extensive evidence is available for the early stages of English acquisition that indicates young children are likely to optionally omit the finiteness markers at the same time they can also produce them correctly, as if they consider finiteness marking to be optional instead of obligatory in simple clauses (Guasti, 2016; Wexler, 1994). Little is known about finiteness marking in complex sentences such as Item 17, although such sentences provide a possible experimental paradigm for investigation. In effect, the sentence in Item 17 allows for an error to be one of overt marking of finiteness on a verb site not licensed for finiteness (i.e., not an omission error but instead an error in choice of overt verb morphology to insert finiteness marking where it is not allowed).

Table 1 displays the four possible conditions in the grammaticality judgments of complex sentences task (i.e., GJ Complex) used in this study based on the sentence structure of Item 17: Missing Do (as in Item 15 above), in which a child could assume the early childhood error of Item 15 would be considered grammatical in Item 17; Ungrammatical Lexical context, in which a child could assume omitted finiteness marking on the lexical verb “paint” was grammatical (as in Item 16 above with omitted –ed); Ungrammatical Do + Lex, in which a child could assume finiteness was not needed in complex sentences (as in Item 17 above in which did and –ed could be omitted); or Double Tense, in which a child could assume that the upper did was not blocking the following second verb say from tense marking, such that say could become said for past tense marking in all three verb positions, although only two sites are licensed for finiteness marking in the adult grammar. Children's responses to this Double Tense item are expected to differ from the first three items.

Table 1.

GJ Complex task: Example sentence in each category.

| Grammatical control item | When | did | the | man | say | he | painted | a | door? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Do | When | ___ | the | man | say | he | painted | a | door? |

| Ungrammatical Lex | When | did | the | man | say | he | paint__ | a | door? |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | When | ___ | the | man | say | he | paint__ | a | door? |

| Double Tense | When | did | the | man | said | he | painted | a | door? |

Note. Underlines indicate sections of the sentence omitted or switched to past tense from the control sentence. All items come from the Rice Grammaticality Judgment Task–Complex Questions. The experimental task and individual items within the task are copyrighted and reprinted with permission. GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Our predictions were as follows: (a) Growth will be evident in typically developing children ages 5–18 years as they learn to overcome an early acceptance of omitted finiteness marking in complex sentences; (b) children with SLI will lag behind their healthy peers in accuracy of grammatical judgments; and (c) these requirements of complex morphosyntax will remain apparent in models controlling for any group differences in child nonverbal IQ, maternal education (in keeping with previous longitudinal studies), or child sex. An open question is whether there are interactions between SLI and the covariates on level of performance or growth over time for each of the four grammatical judgment outcomes. For example, is the effect of SLI on performance moderated by nonverbal IQ or maternal education, and does the impact of SLI on performance vary across boys and girls?

In terms of outcomes, of the four item sets, Double Tense is expected to result in lower performance, especially for the SLI group, given its inconsistency with the other types of omission errors. As shown in Item 17 above, the Double Tense item set includes two finiteness marking sites and one nonfinite site within the same sentence; the Double Tense error can occur if a child accepts a second tense–marked verb when finiteness is blocked by a prior “did.” Finally, the design of the GJ Complex task addresses potential unintended effects of experimental tasks used in previous studies. For example, lexical items and base morphosyntactic structures are the same across conditions, thereby reducing potential attention, meaning, or syntactic confounds, and sentence lengths are very similar across conditions, thereby reducing potential confounds in verbal memory requirements. In short, sentence length, syntactic site, and meaning are controlled across the conditions.

Goals of This Study

The overarching goal of this study was to model the developmental outcomes of growth over time in four types of complex grammatical judgments, including (a) Missing Do, (b) Ungrammatical Lex, (c) Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and (d) Double Tense. Performance was examined in SLI-affected and -unaffected children. Our primary hypothesis was that SLI-affected children would score lower than unaffected children on all GJ Complex outcomes and that these differences would be stable across the age range examined in this study. We then examined the extent to which covariates, including child nonverbal IQ, maternal education, and child sex, predicted overall performance and growth over time in the four outcomes. We predicted that significant SLI group effects would remain after adjustments by these covariates across models.

Our analyses addressed the following questions:

What is the baseline growth for each outcome across all children?

Do SLI-affected children differ from unaffected children in their level of performance at the intercept and in their growth over time for each outcome?

Do covariates of child nonverbal IQ, maternal education, and child sex significantly predict level of performance and rate of change in each outcome?

Are there significant interactions between SLI and the covariates over time?

Method

Ethics

This study was approved by the by the University of Kansas Institutional Review Board (#8223). Small reimbursements for effort were provided to participants, including toys for young children, gift cards for older children, and check payments to parents.

Participants

Participants were drawn from an archival database of a 25-year longitudinal study of children with SLI and their siblings, as well as control children and their siblings (Rice & Hoffman, 2015; Rice et al., 2009, 2010). The parent study is family based for planned pedigree-based genetic studies. All children who met the inclusionary criteria described below were included in this study. For the initial recruitment of an affected child, children were recruited from speech pathologists in public schools (> 100 schools and attendance centers in the Midwestern United States). Over the extended years of the study, most of the children in the SLI group were not receiving speech pathology services beyond the early elementary school grade, per parent report. Thus, this repeated-measures study design is observational, not intended to evaluate training effectiveness.

Children were monolingual native speakers of English in homes using General American English (GAE) as a dialect (Oetting, 2020). Children with suspected dialectal variation from GAE were administered the screening test of the Diagnostic Evaluation of Language Variation (Seymour et al., 2003); children who met criterion for dialectal variation were not included in the study. All target children with SLI and control children were screened for intellectual functioning at the initial assessment collected during recruitment, defined as a score of 85 or above on an age-appropriate test of nonverbal IQ (see Measures section). Siblings and child extended family members were recruited following enrollment of the target children, regardless of their scores on the initial nonverbal IQ assessment. These child family members were included in this study if they met the following criteria for nonverbal IQ: (a) Their score at the initial assessment (ages 5+ years) was 83 or above, or (b) their scores averaged across the first three measurement occasions (ages 5+ years) were 83 or above. No participants had a diagnosis of autism, intellectual, behavioral, or social impairments; all participants passed a hearing screening, collected off-site, using 25 dB (30 dB in noisy environments) at 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz.

The archival database consisted of a total of 483 individuals from 238 families, 60% boys and 40% girls. The number of participants per family, which included some extended family members, ranged from 1 to 12 (M = 2.03, SD = 1.27). For this study, 213 children were classified as unaffected and 270 were classified as SLI affected based on their language score at their first measurement. The age range was 5–18 years, with the average age at the first GJ Complex assessment of 8;1 (range: 5;0–16;9). Participants were assessed every 6 months in the age range of 5–8 years and annually for ages 9–18 years. The number of measurement occasions per person ranged from 3 to 17 (M = 8.59, SD = 3.47), for a total of 4,148 observations in the analysis; children with fewer than three measurement occasions were excluded from analysis. The race percentages were consistent with regional census data: 80.33% White, 0.83% Black, 4.97% American Indian, 12.42% multiracial, and 1.45% unknown or not reported; 6.63% reported as Hispanic.

Procedure

The methods of data collection for the archival database followed an accelerated longitudinal design with rolling recruitment (i.e., children varied continuously in age at first assessment), resulting in multiple age cohorts. Longitudinal data were collected on members of each cohort, except for parents who were only tested once and were not included in this article. Beginning in January 2002, the GJ Complex task was administered every 6 months through 8 years of age and at 12-month intervals thereafter. To lessen demands on the families and to encourage ongoing participation, trained examiners traveled to the participants' home or school and collected data in vans customized for mobile testing. Assessments were administered by an individual examiner to an individual participant in sessions of approximately 15 min as part of a longer study protocol.

Measures

Exclusionary and Inclusionary Assessments for SLI Affectedness

Nonverbal IQ was determined by age-appropriate measures at initial assessment, which, for the purpose of this study, was considered to start at the age of 5 years to align with the minimum age for longitudinal modeling of the study outcomes. Measures of nonverbal IQ included the Columbia Mental Maturity Scale (Burgemeister et al., 1972) for ages 5;0–5;11, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition (WISC-III; Wechsler, 1991) for ages 6;0–15;11, and the WISC-III and the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (Wechsler, 1997) for those starting at 16 years of age, which was the oldest starting age in the analysis. As mentioned previously, all children in this study met inclusion criteria for an initial nonverbal IQ score of 83 or higher.

Determination of SLI affectedness status for this study was based on participants' scores on one of the following age-appropriate omnibus language tests at study entry: (a) Test of Language Development–Primary: Second Edition (TOLD-P:2; Newcomer & Hammill, 1988) from 4 to 5;11 and (b) the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Third Edition (CELF-3; Semel et al., 1995) from 6+ years. Participants with a standard score of < 86 (i.e., ≤ 16th percentile) were classified as SLI affected, and those scoring ≥ 86 were classified as unaffected. The SLI-affected group also included SLI probands recruited into the study based on performance in the affected range on the Test of Early Language Development–Third Edition (Hresko et al., 1999) from 2 to 3;11 or on the TEGI (Rice & Wexler, 2001) from 2;6 to 8;11, where performance of ≤ 1 SD below the mean is considered affected. Using these criteria, of the full sample of N = 483, at the first time of measurement, 56% were classified as SLI affected and 44% were classified as unaffected. These outcomes were similar across the CELF-3, the TOLD-P:2, and the TEGI.

Longitudinal data can vary in its consistency of measurement over time, and measurement inaccuracy could contribute to error variance, thereby working against the study hypotheses. We examined the consistency of age-appropriate mean omnibus language scores (TOLD-P:2 or CELF-3) across age levels/times of measurement for unaffected and affected participants. Figure 1 shows the omnibus standard score means across SLI-affected and -unaffected participants (generated for descriptive purposes using a saturated means three-level model using age integer instead of exact age). Across the full age span of 5–18 years, the mean levels of omnibus test scores are level, with small variance estimates around the means at each time of measurement, for both groups. Furthermore, the difference between the two groups is steady over time. The unaffected group, as expected from valid and reliable testing, maintains a mean level of performance, near or at 100, across the 14 years of assessment, equivalent to the 50th percentile throughout. The mean for the affected group, in contrast, hovered near or at the 9th percentile throughout. Both groups showed little variance around the standard score, with standard error estimates around 1 standard score point. Thus, the measurements appear to be consistent over time, the affected group did not close the gap with age, and the transition from TOLD-P:2 to CELF-3 measurements played out seamlessly.

Figure 1.

Mean omnibus language scores across age for unaffected and affected participants. A standard score of 100 is equivalent to the 50th percentile of the normative sample.

Family Questionnaire

Maternal education was obtained from a family questionnaire at the first time of measurement, with the following categories: some high school, high school graduate or general equivalency diploma (GED), some college, bachelor's degree, some graduate school, and graduate degree.

Experimental GJ Complex Task

The GJ Complex task includes 25 past tense questions that the child listens to and responds with their judgment as to whether the sentence sounds “right” (grammatical) or “not so good” (ungrammatical), beginning with three practice items that can be repeated, if necessary, for understanding the instructions. The task is structured such that there are five “core” sentences that are each presented a total of 5 times each: once as a grammatically well-formed sentence and 4 times in an ungrammatical format. As shown in Table 1 using an example item, the sites in the sentence that mark tense are manipulated in four distinct ways, resulting in the following ungrammatical variations: (a) Missing Do (omission of past tense form of DO), (b) Ungrammatical Lex (lexical verb changed from past to present), (c) Ungrammatical Do + Lex (omission of past tense form of DO and lexical verb changed from past to present), and (d) Double Tense (verb switched to past tense results in a double marking for past tense).

The sentence items (five grammatical and 20 ungrammatical) were presented in the same randomized fashion across participants, with no more than five consecutive ungrammatical items. The task was administered via headphones using an audio recording of the sentences with a female voice in natural prosody. The examiner recorded the participant's oral judgments on a hard copy of the assessment document.

Training and Reliability

The examiners consisted of doctoral students and full-time laboratory staff. The examiners were not blind to the affectedness status of the children. Training involved extensive practice administration and scoring of the standardized measures and GJ Complex task, followed by ongoing monitoring, all under the supervision of a lead examiner and study principal investigator (PI). As part of their training, examiners (a) read the test manuals for standardized measures and internal documentation on the GJ Complex task, (b) viewed videos of test administration on study children, (c) practiced administration of all tasks on an experienced laboratory staff member until they were knowledgeable about and at ease in administering the tasks, (d) practiced administration on at least three typically developing children not enrolled in the study while the lead examiner and PI observed and provided feedback afterwards, (e) viewed an experienced examiner administer the full protocol to a study child in the field, and (f) administered the full protocol to a study child in the field under the supervision of an experienced examiner. Training steps were repeated if necessary. Regular validity checks were performed by trained research assistants who viewed videos of data collection and noted any deviations from the standard protocol. Sessions were regularly observed in the field by the lead examiner to ensure consistency in administration across examiners. Each assessment was scored at least twice, once by the examiner who collected the measure and a second time by an examiner who checked the original scoring for accuracy. If errors were found in the original scoring, a third examiner reconciled the two scores. For the GJ Complex task in this study, if the agreement between scorers was less than 90%, further validity checks of test administration and scoring were conducted of the individual examiner. Data were entered into SPSS by undergraduate student workers, and regular data audits were performed by the data manager to monitor and ensure integrity of the data.

Results

Calculation of Dependent Variables for the GJ Complex Task

As described previously (e.g., Rice et al., 1999, 2009), A′ was calculated to create dependent variables for each of the four ungrammatical sentence variations using the formula from (Linebarger et al., 1983):

| (1) |

where = the proportion of false alarms (i.e., number of “right” responses to ungrammatical items divided by the number of “right” responses to both ungrammatical and grammatical items) and = proportion of hits (i.e., number of “right” responses to grammatical items divided by number of “right” responses to both ungrammatical and grammatical items). A′ adjusts for the tendency in children to respond affirmatively and can then be interpreted as the proportion correct on a two-alternative (i.e., grammatical vs. ungrammatical) forced-choice procedure (Green, 1964; Grier, 1971). Note that for this interpretation to hold, an equal number of grammatical and ungrammatical items must be entered into the formula above, and complete responses to all items are necessary, as was the case here. Thus, the responses to the five grammatical control items were entered into each calculation of A′ used to create the four outcome variables. The resulting A′ values can be interpreted as follows: The highest possible is 1.00, indicating perfect discrimination of grammatical from ungrammatical items; A′ = .50 indicates responses of “right” to both item types, and A′ < .50 indicates predominately “not so good” responses to both item types.

Table 2 shows A′ descriptive data for the four types of grammatical judgments from 5 to 18 years of age for unaffected and SLI-affected participants. The 4,148 administrations of the GJ Complex assessment yielding four A′ outcomes resulted in 16,592 total data points. Children enter the table calculations more than once due to longitudinal testing, with an average of eight occasions each. The highest number of participants are in the younger age groups, peaking at 8 years of age and declining thereafter, with the sample n falling below 100 in some cells from 16 to 18 years of age.

Table 2.

Group means and standard deviations for each GJ Complex A′ outcome per age level.

| GJ Complex outcome | Age level | Unaffected (Child n = 213) |

SLI affected (Child n = 270) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | ||

| Missing Do | 5–5;11 | 172 | 0.56 | 0.23 | 141 | 0.49 | 0.22 |

| Missing Do | 6–6;11 | 207 | 0.69 | 0.23 | 221 | 0.55 | 0.23 |

| Missing Do | 7–7;11 | 222 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 259 | 0.63 | 0.24 |

| Missing Do | 8–8;11 | 222 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 278 | 0.68 | 0.24 |

| Missing Do | 9–9;11 | 127 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 198 | 0.70 | 0.25 |

| Missing Do | 10–10;11 | 122 | 0.82 | 0.22 | 182 | 0.68 | 0.24 |

| Missing Do | 11–11;11 | 131 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 173 | 0.73 | 0.24 |

| Missing Do | 12–12;11 | 136 | 0.87 | 0.19 | 162 | 0.73 | 0.24 |

| Missing Do | 13–13;11 | 132 | 0.85 | 0.19 | 151 | 0.72 | 0.25 |

| Missing Do | 14–14;11 | 111 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 144 | 0.75 | 0.22 |

| Missing Do | 15–15;11 | 100 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 125 | 0.74 | 0.22 |

| Missing Do | 16–16;11 | 79 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 108 | 0.68 | 0.27 |

| Missing Do | 17–17;11 | 53 | 0.91 | 0.11 | 91 | 0.74 | 0.25 |

| Missing Do | 18–18;11 | 42 | 0.90 | 0.14 | 59 | 0.78 | 0.22 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 5–5;11 | 172 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 141 | 0.48 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 6–6;11 | 207 | 0.71 | 0.23 | 221 | 0.55 | 0.24 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 7–7;11 | 222 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 259 | 0.64 | 0.25 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 8–8;11 | 222 | 0.79 | 0.22 | 278 | 0.69 | 0.24 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 9–9;11 | 127 | 0.81 | 0.20 | 198 | 0.71 | 0.22 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 10–10;11 | 122 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 182 | 0.71 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 11–11;11 | 131 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 173 | 0.75 | 0.21 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 12–12;11 | 136 | 0.86 | 0.19 | 162 | 0.73 | 0.25 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 13–13;11 | 132 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 151 | 0.73 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 14–14;11 | 111 | 0.84 | 0.20 | 144 | 0.73 | 0.21 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 15–15;11 | 100 | 0.85 | 0.20 | 125 | 0.71 | 0.26 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 16–16;11 | 79 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 108 | 0.71 | 0.24 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 17–17;11 | 53 | 0.89 | 0.15 | 91 | 0.70 | 0.21 |

| Ungrammatical Lex | 18–18;11 | 42 | 0.89 | 0.14 | 59 | 0.71 | 0.22 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 5–5;11 | 172 | 0.59 | 0.23 | 141 | 0.52 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 6–6;11 | 207 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 221 | 0.57 | 0.25 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 7–7;11 | 222 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 259 | 0.68 | 0.25 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 8–8;11 | 222 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 278 | 0.72 | 0.24 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 9–9;11 | 127 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 198 | 0.77 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 10–10;11 | 122 | 0.88 | 0.19 | 182 | 0.78 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 11–11;11 | 131 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 173 | 0.82 | 0.19 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 12–12;11 | 136 | 0.90 | 0.19 | 162 | 0.80 | 0.23 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 13–13;11 | 132 | 0.90 | 0.17 | 151 | 0.81 | 0.24 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 14–14;11 | 111 | 0.91 | 0.18 | 144 | 0.83 | 0.22 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 15–15;11 | 100 | 0.90 | 0.20 | 125 | 0.81 | 0.22 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 16–16;11 | 79 | 0.92 | 0.18 | 108 | 0.79 | 0.26 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 17–17;11 | 53 | 0.96 | 0.10 | 91 | 0.76 | 0.25 |

| Ungrammatical Do + Lex | 18–18;11 | 42 | 0.93 | 0.18 | 59 | 0.84 | 0.21 |

| Double Tense | 5–5;11 | 172 | 0.54 | 0.20 | 141 | 0.48 | 0.22 |

| Double Tense | 6–6;11 | 207 | 0.63 | 0.23 | 221 | 0.54 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 7–7;11 | 222 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 259 | 0.59 | 0.21 |

| Double Tense | 8–8;11 | 222 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 278 | 0.62 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 9–9;11 | 127 | 0.77 | 0.24 | 198 | 0.61 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 10–10;11 | 122 | 0.82 | 0.22 | 182 | 0.62 | 0.25 |

| Double Tense | 11–11;11 | 131 | 0.84 | 0.22 | 173 | 0.66 | 0.24 |

| Double Tense | 12–12;11 | 136 | 0.89 | 0.16 | 162 | 0.69 | 0.25 |

| Double Tense | 13–13;11 | 132 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 151 | 0.68 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 14–14;11 | 111 | 0.87 | 0.17 | 144 | 0.71 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 15–15;11 | 100 | 0.89 | 0.17 | 125 | 0.73 | 0.25 |

| Double Tense | 16–16;11 | 79 | 0.91 | 0.17 | 108 | 0.71 | 0.23 |

| Double Tense | 17–17;11 | 53 | 0.94 | 0.13 | 91 | 0.74 | 0.25 |

| Double Tense | 18–18;11 | 42 | 0.94 | 0.14 | 59 | 0.73 | 0.24 |

Note. Children were tested twice per year through 8 years of age and annually thereafter. Calculations are per age level, with children entering the table more than once due to longitudinal testing. GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Predictors of Grammatical Judgment Outcomes

Children's exact age on each occasion was a time-varying continuous predictor, which was centered at 10 years of age. Time-invariant predictors included exact age at the first GJ Complex measure from 5 years of age onward (age cohort; centered at 8 years), SLI affectedness (0 = no, 1 = yes), child sex (0 = girls, 1 = boys), child nonverbal IQ standard score from 5 years of age onward (centered at 100), and maternal education (some high school, high school graduate or GED, some college, bachelor's degree, some graduate school, or graduate degree). Given preliminary analyses showing no improvement in fit as a categorical predictor, maternal education was modeled as an interval predictor in the models reported below (centered such that 0 = high school graduate or GED).

Predicted means, standard errors, and confidence intervals for these key time invariant characteristics at the initial assessment are shown in Table 3 for unaffected (n = 213) and SLI-affected (n = 270) participants. The means and group comparisons were provided via the LSMEANS statement within SAS Proc Mixed, Version 9.4 in models that included a random intercept variance component for relatedness of children within families. As shown, the average scores for omnibus language, nonverbal IQ, and maternal education were significantly lower in the SLI-affected group; this is consistent with what is known about groups of children identified as SLI as defined here (i.e., by omnibus language scores given nonverbal IQ scores of > 82). More precise estimates of longitudinal group differences were then obtained from the multilevel models of growth across age in the four types of complex grammatical judgments, as described next.

Table 3.

Predicted means (M), standard errors (SE), and confidence intervals (CI) for key variables for unaffected and SLI-affected participants on initial assessment.

| Variable | Unaffected (n = 213) |

SLI affected (n = 270) |

Group comparisons |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | 95% CI |

M | SE | 95% CI |

t | df | Cohen's d | |||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | ||||||||

| First GJ age yearsa | 8.09 | 0.21 | 7.67 | 8.51 | 8.13 | 0.19 | 7.75 | 8.50 | −0.14 | 478 | −0.01 |

| Omnibus languageb | 100.63 | 0.65 | 99.36 | 101.91 | 78.13 | 0.58 | 76.99 | 79.28 | 26.47 | 483 | 2.41 |

| Nonverbal IQc | 104.23 | 0.77 | 102.71 | 105.74 | 98.27 | 0.70 | 96.88 | 99.65 | 6.13 | 471 | 0.56 |

| Maternal educationd | 3.49 | 0.09 | 3.31 | 3.67 | 3.36 | 0.09 | 3.18 | 3.54 | 2.97 | 265 | 0.36 |

Note. Bold values indicate p < .01. SLI = specific language impairment; LL = lower limit; UL = lower limit; GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Age in years at first GJ Complex assessment.

First available of Test Language Development–Primary: Second Edition or Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Third Edition.

Columbia Mental Maturity Scale, Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children–Third Edition, or Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition (first available starting at 5 years of age).

Coded where 1 = some high school, no diploma; 2 = high school graduate, diploma, or general equivalency diploma; 3 = some college, no degree; 4 = bachelor's degree; 5 = some graduate work; 6 = graduate degree.

Model Specification

Growth over time in each type of grammatical judgment as indexed by A′ was assessed using multilevel models in which time was nested within persons and persons were nested within families, creating a three-level model. All models were estimated using maximum likelihood and Satterthwaite denominator degrees of freedom within SAS Proc Mixed. The significance of individual fixed effects was evaluated via their Wald test p values, whereas the significance of multiple fixed effects or of random effects variances and covariances was evaluated via −2ΔLL tests (i.e., likelihood ratio tests using degrees of freedom equal to the difference in the number of estimated parameters). In both cases, p values of < .01 were considered significant. Linear combinations of model fixed effects (i.e., to obtain simple effects within interaction terms) were obtained via ESTIMATE and LSMEANS statements, which then provide an estimate, standard error, and corresponding p value for all requested model-implied fixed effects.

Given that standardized coefficients do not exist for three-level models such as ours, effect sizes are often created as the proportion of each variance component accounted for by the predictors, pseudo-R2 (Singer & Willett, 2003). However, given that our conditional growth models included up to six separate variance components across levels, an alternative, more transparent measure of effect size of total R2 was selected (Hoffman, 2015). Total R2 was calculated for each model as the squared correlation between the actual outcomes and the outcomes predicted by the model fixed effects (i.e., analogous to R2 in a single-level regression). To supplement total R2 as a general effect size, we also provide partial Cohen's d in a standardized mean difference metric for significant group differences (e.g., SLI affected vs. unaffected), as well as partial eta (η) in a correlation metric for significant slopes for continuous predictors (e.g., nonverbal IQ). “Partial” refers to the unique contribution of each predictor after controlling for its overlap with other predictors in the model. Effect sizes were calculated using the t values and denominator degrees of freedom (df) for the model fixed effects, using the formulas below (Darlington & Hayes, 2016).

| (2) |

| (3) |

With respect to the modeling sequence, an unconditional means (i.e., empty means or random intercept only) model was first estimated to describe the variation at each level of analysis for the four outcomes. Fixed and random effects of time-varying age were then examined in unconditional growth models, as well as effects of age cohort (as explained below). Next, SLI affectedness and its interactions with time were examined, followed by the time-invariant covariates of child nonverbal IQ, maternal education, and child sex and their interactions with time in a final model to examine the extent to which these predictors could account for individual differences in growth in grammatical judgments. An additional model was then estimated that included interactions between SLI and each covariate, as well as SLI by covariate by time, to determine if any of the significant covariate effects varied as a function of the SLI group.

Proportions of Variance Across Time, Person, and Family

Of the total variance in complex grammatical judgments to Missing Do, 68% was over time within persons (Level 1), 24% was across persons within families (Level 2), and 8% (Level 3) was between families. Consequently, the Level 2 intraclass correlation reflecting the proportion of variance due to between-persons mean differences (at Levels 2 and 3; 24% + 8%) was .32; of that 32%, the Level 3 intraclass correlation for the proportion due to between-families mean differences (at Level 3) was 24%.

For Ungrammatical Lex, 68% of the total variance was over time within persons (Level 1), 21% was across persons within families (Level 2), and 11% (Level 3) was between families. The intraclass correlation indicated that 32% of variance was due to between-persons mean differences (at Levels 2 and 3), and of that .32, the proportion due to between-families mean differences at Level 3 was 34%.

For Ungrammatical Do + Lex, 66% of the total variance was over time within persons (Level 1), 23% was across persons within families (Level 2), and 10% (Level 3) was between families. The intraclass correlation indicated that 34% of variance was due to between-persons mean differences (at Levels 2 and 3), and of that .34, the proportion due to between-families mean differences was 31%.

For Double Tense, 69% of the total variance was over time within persons (Level 1), 19% was across persons within families (Level 2), and 12% (Level 3) was between families. The intraclass correlation indicated that 31% of variance was due to between-persons mean differences (at Levels 2 and 3), and of that .31, the proportion due to between-families mean differences at Level 3 was 39%. Each of the above Level 3 intraclass correlations was significantly greater than 0 (ps < .01), indicating the need for a three-level model for time within person within family in modeling growth across age in the four grammatical judgment outcomes.

Question 1: Baseline (Unconditional) Growth Models

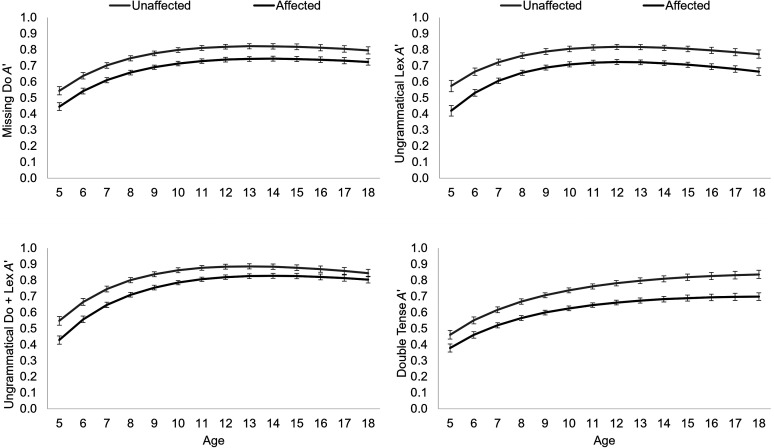

The A′ expected means across age for each grammatical judgment outcome are shown in Figure 2 (i.e., as generated for descriptive purposes separately by outcome using a saturated means three-level model on age integer instead of exact age). Given the exponential patterns of growth observed, the time-varying predictor of age and the time-invariant predictor of age cohort (i.e., age at first GJ Complex assessment) were log-transformed and then centered at log-age 10 and 8 years, respectively. This allowed for the linear age slope to approximate this exponential-type growth trend (Singer & Willett, 2003). Higher order quadratic effects of log-age were also examined and retained when significant, which resulted in a gradual increase in A′ from ages 5 to 11 years that leveled off thereafter. The fixed linear and quadratic effects of log-age accounted for 9.87% of the total variance for Missing Do, 8.48% for Ungrammatical Lex, 13.25% for Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and 12.23% for Double Tense.

Figure 2.

A′ performance across age for all GJ Complex outcomes. A′ values are saturated means generated from separate statistical models placed in the same figure for visual comparison. GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Individual differences in growth were then examined. For Missing Do, significant individual differences were found across persons in linear growth, −2ΔLL(2) = 32.22, p < .001, and quadratic growth, −2ΔLL(3) = 20.26, p < .001, but not across families. For Ungrammatical Lex, significant individual differences were found across persons in linear growth, −2ΔLL(2) = 37.23, p < .001, and quadratic growth, −2ΔLL(3) = 36.78, p < .001, but these random slopes were not estimable across families. For Ungrammatical Do + Lex, significant individual differences were found across persons in linear growth, −2ΔLL(2) = 65.71, p < .001, and quadratic growth, −2ΔLL(3) = 21.34, p < .001, but not across families. Finally, for the Double Tense outcome, significant individual differences were found across persons in linear growth, −2ΔLL(2) = 59.33, p < .001, but not across families. Models including individual differences in quadratic growth at the person and family levels were not estimable for the Double Tense outcome.

Because the participants in this accelerated longitudinal design ranged in age from 5;0 to 16;9 at their first GJ Complex assessment, 50% of the variation in log-age actually reflected cross-sectional differences. Accordingly, a time-invariant continuous predictor, labeled age cohort, for participant's exact log-age at study entry (centered at log-age 8 years) was used to model the differential effects of cross-sectional age. Table 4 shows the final unconditional growth models after including effects of age cohort. Effects of age cohort on the linear and quadratic log-age slopes were examined but were not significant. A linear effect of age cohort significantly moderated the intercept and accounted for an additional 0.05% of the variance in A′ outcomes for Missing Do, 0.13% of the variance for Ungrammatical Lex, and 0.14% of the variance for Ungrammatical Do + Lex. Across these judgment types, A′ values were higher across log-age by .07 to .09 per year when entering the study. For Double Tense, the intercept was moderated by both linear and quadratic effects of log-age cohort, which accounted for an additional 1.62% of the total variance. A′ was nonsignificantly lower across log-age by .03 for each year older when entering the study; however, the linear log-age cohort effect became more positive by twice the quadratic cohort effect of .31 for each year older at study entry. In other words, there was an accelerating positive function across start age on the intercept.

Table 4.

Unconditional growth model parameters.

| Parameter | Missing Do Total R2 = .099 |

Ungrammatical Lex Total R2 = .086 |

Ungrammatical Do + Lex Total R2 = .134 |

Double Tense Total R2 = .138 |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||||||||

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Int (age 10 years) | .77 | .01 | .75 | .78 | .001 | .78 | .01 | .76 | .80 | .001 | .83 | .01 | .81 | .85 | .001 | .68 | .01 | .65 | .70 | .001 |

| Linear age slope | .16 | .02 | .14 | .19 | .001 | .14 | .02 | .11 | .17 | .001 | .20 | .02 | .16 | .23 | .001 | .27 | .02 | .24 | .30 | .001 |

| Quad age slope | −.28 | .03 | −.34 | −.22 | .001 | −.34 | .03 | −.41 | −.28 | .001 | −.36 | .03 | −.42 | −.30 | .001 | −.19 | .03 | −.25 | −.13 | .001 |

| Linear age cohort | .09 | .02 | .04 | .13 | .001 | .07 | .02 | .02 | .11 | .004 | .07 | .02 | .03 | .12 | .001 | −.03 | .02 | −.08 | .02 | .194 |

| Quad age cohort | .31 | .07 | .17 | .45 | .001 | |||||||||||||||

| Random effects: Variance components | ||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 residual | .04 | .00 | .04 | .04 | .001 | .03 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .001 | .03 | .00 | .03 | .03 | .001 | .04 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .001 |

| L2 int | .02 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .001 |

| L2 linear | .01 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .001 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .04 | .001 | .03 | .01 | .02 | .04 | .001 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .001 |

| L2 quad | .03 | .03 | .01 | .37 | .101 | .11 | .03 | .07 | .21 | .001 | .06 | .03 | .03 | .19 | .018 | |||||

| L2 int–linear | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .793 | .00 | .00 | −.01 | .00 | .403 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .001 |

| L2 int–quad | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .001 | −.03 | .01 | −.04 | −.02 | .001 | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .001 | |||||

| L2 linear–quad | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | .00 | .018 | .00 | .01 | −.02 | .01 | .797 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .03 | .083 | |||||

| L3 int | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 |

Note. The time-varying predictor of age and the effects of age cohort were log-transformed. The intercept parameter is time-varying log-age, centered at log-age 10 years, and represents the average A′ outcome at 10 years of age. The estimates for linear and quadratic effects of age cohort represent the cross-sectional effects of children's exact age at study entry, centered at log-age 8 years, on the intercept. Bold values indicate p < .01. Covariances indicated with dash (–). Blank cells indicate effects not included in a particular model due to nonsignificance. Est = estimate; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; Int = intercept; Quad = quadratic; L1 residual = variance over time and within persons; L2 = Level 2: variance across persons within families; L3 = Level 3: variance within families.

Questions 2–3: Conditional Growth Models

SLI Affectedness

Next, given the presence of significant individual differences in the linear effect of log-age for each of the outcomes, the main effect of SLI and its pertinent interactions with log-age were added to each model, which yielded the following increase in total variance for each outcome: 5.39% for Missing Do, 7.19% for Ungrammatical Lex, 5.31% for Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and 8.55% for Double Tense. As shown in Figure 3, the main effect of SLI affectedness was a significant predictor of A′ for all four grammatical judgment outcomes, such that SLI-affected children had lower A′ by approximately .12 on average (range: −.10 to −.15) at 10 years of age. The performance gap between the SLI-affected and -unaffected groups persisted across age (i.e., no significant SLI interactions with log-age) for all outcomes except Double Tense. As shown in Figure 3 (bottom right), SLI-affected children had similar Double Tense A′s as SLI-unaffected children at 5 years of age, but starting at 6 years of age, the predicted A′ scores between the two groups grew apart, such that the SLI-unaffected children had significantly higher A′ than SLI-affected children at all other ages. This was due to a significant SLI by linear log-age slope interaction of −.08. However, in the full model with all covariates to follow, the SLI by linear log-age slope interaction for Double Tense was not significant, such that, similar to the other A′ outcomes, the SLI-affected children performed lower on Double Tense A′ than unaffected children at all ages.

Figure 3.

Effects of SLI affectedness on the four GJ Complex A′ outcomes. SLI = specific language impairment; GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Final Models With Covariates

Initial child nonverbal IQ, maternal education, child sex, and their interactions with linear and quadratic log-age were then added to each grammatical judgment model. Shown in Table 5 and discussed here are the final conditional growth models after removing nonsignificant higher order interactions with quadratic log-age. As shown in Figure 4 and Table 5, SLI remained a significant predictor of A′ across age for all outcomes, even after including covariates and their interactions with log-age. The addition of covariates and their interactions with log-age in the final models accounted for another 2.07% of variance for Missing Do, 2.30% of variance for Ungrammatical Lex, 2.66% of variance for Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and 1.70% for Double Tense. The corresponding partial Cohen's d and partial eta (η) effect sizes for the fixed effects in these models are shown in Table 6. For the significant effects of SLI group differences on the intercept, d = −0.63 for Missing Do, d = −0.58 for Ungrammatical Lex, d = −0.62 for Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and d = −0.89 for Double Tense. Thus, after accounting for all other predictors in the model, the average predicted A′ in the SLI-affected group was 0.58–0.89 SDs lower than the average predicted A′ in the unaffected group.

Table 5.

Final conditional growth model parameters.

| Parameter | Missing Do Total R2 = .174 |

Ungrammatical Lex Total R2 = .181 |

Ungrammatical Do + Lex Total R2 = .214 |

Double Tense Total R2 = .241 |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||||||||

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Int (age 10 years) | .80 | .01 | .77 | .83 | .001 | .81 | .02 | .77 | .84 | .001 | .86 | .01 | .83 | .89 | .001 | .74 | .02 | .71 | .77 | .001 |

| Linear age slope | .17 | .03 | .11 | .22 | .001 | .12 | .03 | .06 | .18 | .001 | .19 | .03 | .13 | .25 | .001 | .27 | .03 | .22 | .33 | .001 |

| Quad age slope | −.29 | .03 | −.35 | −.23 | .001 | −.30 | .07 | −.45 | −.16 | .001 | −.38 | .03 | −.44 | −.32 | .001 | −.18 | .03 | −.24 | −.12 | .001 |

| Linear age cohort | .10 | .02 | .06 | .14 | .001 | .08 | .02 | .04 | .12 | .001 | .09 | .02 | .05 | .13 | .001 | −.02 | .02 | −.06 | .03 | .463 |

| Quad age cohort | .19 | .07 | .06 | .31 | .004 | |||||||||||||||

| SLI on int | −.08 | .01 | −.11 | −.06 | .001 | −.10 | .02 | −.13 | −.07 | .001 | −.08 | .01 | −.10 | −.05 | .001 | −.11 | .01 | −.14 | −.09 | .001 |

| SLI on slope | .02 | .02 | −.03 | .07 | .398 | .03 | .03 | −.02 | .08 | .301 | .06 | .03 | .01 | .11 | .022 | −.04 | .03 | −.09 | .01 | .097 |

| SLI on quad | −.08 | .07 | −.22 | .05 | .236 | |||||||||||||||

| NVIQ on int | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .004 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .031 |

| NVIQ on slope | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .210 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .400 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .977 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .096 |

| NVIQ on quad | −.01 | .00 | −.01 | .00 | .003 | |||||||||||||||

| M-Ed on int | .02 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .001 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .02 | .029 | .02 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .001 | .02 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .001 |

| M-Ed on slope | .01 | .01 | −.01 | .03 | .290 | .01 | .01 | −.01 | .03 | .260 | .00 | .01 | −.02 | .02 | .966 | .02 | .01 | .00 | .04 | .019 |

| M-Ed on quad | .01 | .02 | −.03 | .06 | .578 | |||||||||||||||

| BvG on int | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | .00 | .117 | .01 | .02 | −.02 | .04 | .458 | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | .00 | .117 | −.02 | .01 | −.04 | .01 | .166 |

| BvG on slope | −.05 | .02 | −.10 | −.01 | .025 | −.03 | .03 | −.08 | .02 | .301 | −.06 | .03 | −.11 | −.01 | .020 | −.03 | .02 | −.08 | .02 | .239 |

| BvG on quad | −.01 | .07 | −.14 | .11 | .837 | |||||||||||||||

| Random effects: Variance components | ||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 residual | .04 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .001 | .03 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .001 | .03 | .00 | .03 | .03 | .001 | .04 | .00 | .03 | .04 | .001 |

| L2 int | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .001 |

| L2 linear | .01 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .008 | .02 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .001 | .02 | .00 | .02 | .04 | .001 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .001 |

| L2 quad | .03 | .02 | .01 | .33 | .094 | .09 | .03 | .05 | .19 | .001 | .05 | .03 | .02 | .19 | .022 | |||||

| L2 int–linear | .01 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .929 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .622 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 |

| L2 int–quad | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | −.01 | .001 | −.03 | .01 | −.04 | −.02 | .001 | −.02 | .00 | −.03 | −.01 | .001 | |||||

| L2 linear–quad | −.01 | .01 | −.03 | .00 | .023 | .00 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | .961 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .03 | .100 | |||||

| L3 int | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .039 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .012 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .001 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .004 |

Note. The time-varying predictor of age and the effects of age cohort were log-transformed. The estimates for linear and quadratic effects of age cohort represent the cross-sectional effects of children's exact age at study entry, centered at log-age 8 years, on the intercept. The intercept for each GJ Complex outcome reflects the expected A′ score for a 10-year-old girl, without SLI, who entered the study at 8 years of age with average-level performance on nonverbal IQ and whose mother has a high school education or GED. The Est for SLI reflects the difference in A′ score for SLI-affected compared to unaffected children; the Est for NVIQ reflects the increase in A′ score for each one-unit increase in IQ score; the Est for M-Ed reflects the increase in A′ score for each one-unit increase in maternal education; the Est for BvG reflects the difference in A′ score for boys when compared to girls. Bold values indicate p < .01. Covariances indicated with dash (–). Blank cells indicate effects not included in a particular model due to nonsignificance. Est = estimate; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit; Int = intercept; Quad = quadratic; SLI = specific language impairment (0 = unaffected); NVIQ = nonverbal IQ (centered at 100); M-Ed = maternal education (0 = high school/GED); BvG = boys versus girls (0 = girls); L1 residual = variance over time and within persons; L2 = Level 2: variance across persons within families; L3 = Level 3: variance within families; GJ = grammaticality judgment; GED = general equivalency diploma.

Figure 4.

Effects of SLI affectedness on the four GJ Complex A′ outcomes in final models with covariates. SLI = specific language impairment; GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Table 6.

Partial Cohen's d and partial eta (η) effect sizes for fixed effects in the final conditional growth models.

| Parameter | Missing Do |

Ungrammatical Lex |

Ungrammatical Do + Lex |

Double Tense |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total R2 = .174 |

Total R2 = .181 |

Total R2 = .214 |

Total R2 = .241 |

|||||

| d | η | d | η | d | η | d | η | |

| Linear age slope | 0.59 | .28 | 0.40 | .20 | 0.62 | .30 | 0.94 | .42 |

| Quad age slope | −0.96 | −.43 | −0.40 | −.20 | −1.28 | −.54 | −0.25 | −.13 |

| Linear age cohort | 0.37 | .18 | 0.31 | .15 | 0.35 | .17 | −0.06 | −.03 |

| Quad age cohort | 0.25 | .12 | ||||||

| SLI on int | −0.63 | −.30 | −0.58 | −.28 | −0.62 | −.30 | −0.89 | −.41 |

| SLI on slope | 0.09 | .04 | 0.11 | .05 | 0.24 | .12 | −0.17 | −.09 |

| SLI on quad | −0.12 | −.06 | ||||||

| NVIQ on int | 0.26 | .13 | 0.36 | .18 | 0.37 | .18 | 0.20 | .10 |

| NVIQ on slope | 0.13 | .07 | 0.09 | .04 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.17 | .09 |

| NVIQ on quad | −0.31 | −.15 | ||||||

| M-Ed on int | 0.50 | .24 | 0.22 | .11 | 0.43 | .21 | 0.45 | .22 |

| M-Ed on slope | 0.11 | .05 | 0.11 | .06 | 0.00 | .00 | 0.23 | .12 |

| M-Ed on quad | 0.06 | .03 | ||||||

| BvG on int | −0.14 | −.07 | 0.07 | .03 | −0.15 | −.07 | −0.13 | −.06 |

| BvG on slope | −0.24 | −.12 | −0.11 | −.05 | −0.24 | −.12 | −0.12 | −.06 |

| BvG on quad | −0.02 | −.01 | ||||||

Note. Effects sizes shown in bold indicate significant fixed effects at p < .01 in the final models. “Partial” refers to the unique contribution of each predictor after controlling for its overlap with other predictors in the model. Blank cells indicate effects not included in a model due to nonsignificance. Quad = quadratic; SLI = specific language impairment: unaffected (coded as 0) versus SLI affected (coded as 1); int = intercept; NVIQ = nonverbal IQ; M-Ed = maternal education; BvG = boys (coded as 0) versus girls (coded as 1).

Child nonverbal IQ

Initial child nonverbal IQ (see Table 5) was a significant predictor of A′ for all GJ Complex outcomes except Double Tense. Growth trajectories for three levels of nonverbal IQ (−1 SD = 85, average = 100, +1 SD = 115) are shown in Figure 4 for all outcomes. At log-age 10 years, for each one-unit e_k; increase in nonverbal IQ, A′ for Missing Do, Ungrammatical Lex, and Ungrammatical Do + Lex significantly increased by .002. However, as shown in the top right of Figure 5, for the Ungrammatical Lex outcome, the positive linear log-age slope was reduced by twice the quadratic effect of .01 with age. Follow-up tests showed that the predicted main effect of nonverbal IQ on Ungrammatical Lex A′ was significant for ages 8 through 14 years (ps < .01), but not significant before 8 years of age or after 14 years of age (ps > .01). Thus, higher initial nonverbal IQ predicted an advantage on Ungrammatical Lex A′ in middle childhood, but not in younger childhood or older teen years. As shown in Table 6, for the GJ Complex outcomes in which nonverbal IQ was a significant predictor, effect sizes ranged from η = .13 to η = .18.

Figure 5.

Effects of nonverbal IQ on the four GJ Complex A′ outcomes in the final models with covariates. Lines in each figure represent the expected A′ scores for three levels of nonverbal IQ: −1 SD (IQ = 85), average IQ (IQ = 100), and +1 SD (IQ = 115). GJ = grammaticality judgment.

Maternal education

Higher maternal education (see Table 5) significantly predicted higher A′s at log-age 10 years by .02 for Missing Do, Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and Double Tense outcomes, and this effect was stable across log-age (i.e., nonsignificant interactions with linear and quadratic log-age). For these significant effects of maternal education, effect sizes ranged from η = .21 to η = .24. Maternal education was not a significant predictor of Ungrammatical Lex A′.

Child sex

The effect of child sex (see Table 5) was not significant for any of the GJ Complex outcomes, nor were interactions between sex and the linear and quadratic log-age slopes. Put differently, boys and girls did not differ in A′ at log-age 10 years nor did they differ in rate of change in A′ across log-age.

Question 4: Interactions Between SLI and Covariates

Finally, interactions between SLI and all covariates (including their interactions with linear and quadratic log-age) were added to the final model to determine if the effects of SLI were moderated by child nonverbal IQ, maternal education, or child sex. The results from these models are shown in Table 7, and the corresponding effect sizes can be found in Table 8. The addition of these interactions accounted for another 0.08% of variance for Missing Do, 0.26% of variance for Ungrammatical Lex, 0.15% of variance for Ungrammatical Do + Lex, and 0.09% of variance for Double Tense. None of the interactions between SLI and the covariates were significant. Thus, the previously discussed significant effects of SLI were not moderated by any of the covariates.

Table 7.

Conditional growth model parameters including interactions between SLI and covariates.

| Parameter | Missing Do Total R2 = .175 |

Ungrammatical Lex Total R2 = .184 |

Ungrammatical Do + Lex Total R2 = .215 |

Double Tense Total R2 = .242 |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | Est | SE | 95% CI |

p < | |||||

| LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | LL | UL | |||||||||||||

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Int (age 10 years) | .80 | .02 | .77 | .84 | .001 | .82 | .02 | .78 | .86 | .001 | .87 | .02 | .84 | .91 | .001 | .74 | .02 | .70 | .78 | .001 |

| Linear age slope | .19 | .03 | .13 | .26 | .001 | .12 | .04 | .05 | .19 | .001 | .19 | .04 | .12 | .26 | .001 | .28 | .03 | .21 | .35 | .001 |

| Quad age slope | −.29 | .03 | −.35 | −.23 | .001 | −.40 | .09 | −.58 | −.22 | .001 | −.38 | .03 | −.44 | −.32 | .001 | −.18 | .03 | −.24 | −.12 | .001 |

| Linear age cohort | .10 | .02 | .06 | .14 | .001 | .08 | .02 | .04 | .12 | .001 | .09 | .02 | .05 | .14 | .001 | −.01 | .02 | −.05 | .03 | .557 |

| Quad age cohort | .18 | .07 | .06 | .31 | .005 | |||||||||||||||

| SLI on int | −.09 | .02 | −.13 | −.04 | .001 | −.12 | .03 | −.17 | −.06 | .001 | −.08 | .02 | .12 | −.04 | .001 | −.11 | .02 | −.15 | −.07 | .001 |

| SLI on slope | −.03 | .04 | −.12 | .05 | .442 | .02 | .05 | −.08 | .11 | .704 | .05 | .05 | −.04 | .15 | .276 | −.06 | .05 | −.15 | .03 | .188 |

| SLI on quad | .12 | .13 | −.13 | .36 | .365 | |||||||||||||||

| NVIQ on int | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .216 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .088 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .147 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .405 |

| NVIQ on slope | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .264 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .915 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .860 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .780 |

| NVIQ on quad | −.01 | .00 | −.02 | .00 | .026 | |||||||||||||||

| NVIQ × SLI on int | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .231 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .161 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .047 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .276 |