How well do young people with congenital heart disease understand their medical conditions? After interviewing 63 patients aged 7 to 18 years who received care at a tertiary pediatric heart center in England, Veldtman and colleagues observed that only one third understood their illness well and less than one quarter could name their condition.1 From these observations, they concluded that “intensified efforts to ensure better patient and parental understanding are needed.” This conclusion may seem sensible and challenging, requiring developmentally appropriate teaching techniques that recognize children's cognitive abilities and independence from parental figures. Before charging off to design and launch new patient education programs, however, we should consider several essential questions that are relevant to programs for adult patients as well as for children and their parents.

WHAT ARE THE FUNDAMENTAL OBJECTIVES OF PATIENT EDUCATION?

Greater understanding about one's disease is inherently worthy, but only to a limited degree. Knowledge for knowledge's sake is a dubious goal. If patient education is to matter, it needs to improve patients' lives by accomplishing valuable objectives.

Too often, these objectives are never stated. A recent review found that only 40% of published studies on patient education programs for adult patients with asthma specified educational objectives. These objectives were usually to improve disease-specific knowledge or self-management skills.2 Instead of these intermediary goals, more fundamental objectives—such as improved self-esteem or reduced illness-related anxiety or mortality—should be the main outcome measures, and these should ultimately be based on what patients want from their health care.

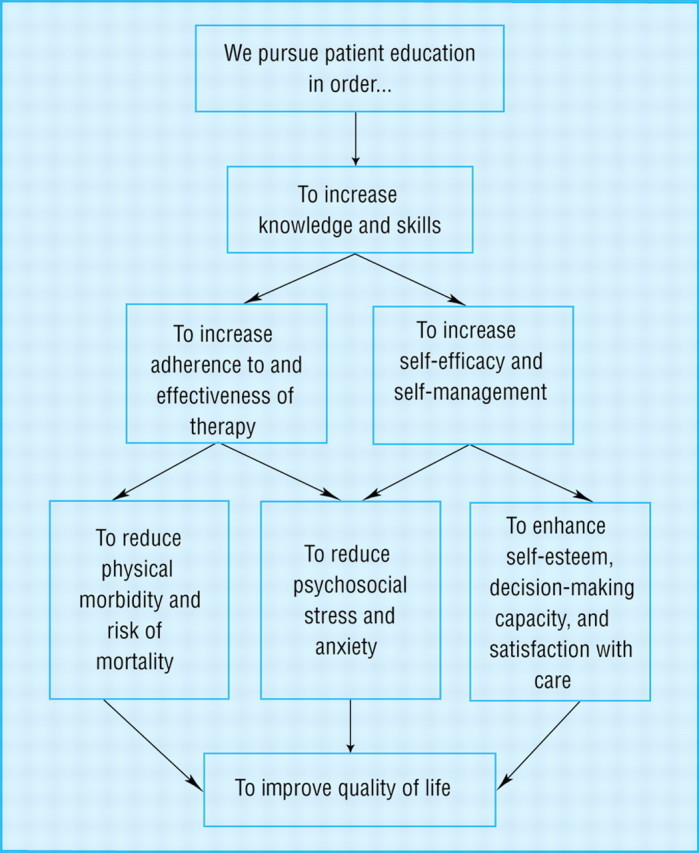

Once identified, these outcome measures can be assembled into a model, the deepest goal of which is to improve patients' quality of life (see figure). Such models also enable insightful evaluation of health care programs and their proposed effects. The figure depicts how accomplishing one objective facilitates the accomplishment of another objective. Different models can be devised, depending both on your theory of how patient education works and on what you (or your patients) value.3

WILL MORE EDUCATION ACHIEVE THESE FUNDAMENTAL OBJECTIVES?

Once the desired effects of a patient education program have been specified, we can ask whether the program works in a way that matters for pediatric patients, their parents, or adult patients. Because new patient education programs are interventions of uncertain effect—positive or negative—they should be studied through randomized controlled trials to test whether they accomplish the most valued objectives. All other objectives, such as increasing illness-specific knowledge or improving adherence to therapy, represent only surrogate end points and should be regarded skeptically, with the studies designed instead to focus on the outcomes that patients value most.

ARE THERE OTHER WAYS TO ACHIEVE THESE FUNDAMENTAL OBJECTIVES?

Specifying ultimate objectives not only ensures that studies answer the right questions, but also enables us to envision other means to desired ends, promoting creative, “out-of-the-box” thinking.4 For example, Veldtman and colleagues propose that, at a time of medical crisis, knowledgeable patients will be able to inform their health care providers regarding their diagnosis.1 If the goal here is to improve the quality of medical care to reduce morbidity and risk of mortality, then perhaps other interventions—such as medical alert bracelets or accessible electronic medical records—would better accomplish these goals. More generally, given the time and money that additional education will consume, we should examine whether we should spend these resources on other psychosocial interventions that have been shown to benefit children with chronic illnesses.5 The best way to answer these questions would be through cost-utility analyses of the findings of controlled comparative trials.

WHAT ARE THE LIMITS OF EDUCATION?

Understanding congenital heart lesions is difficult and eludes many of us who are unable to grasp abstract concepts or comprehend intricate 3-dimensional structures. The same is true of many other complicated medical conditions. Whereas assuming that patients cannot understand is patronizing, subtly insisting that they reach a certain level of knowledge is equally as troublesome. As patient-specific health information becomes more detailed and complicated, we must ask whether additional education will promote the health goals of a particular person, respectfully recognizing differing levels of cognitive ability and not exceeding the limits of education.

As we sally forth into the information age, we should proceed skeptically, assuring that the most valued objectives of chronically ill patients are truly being advanced through health education programs.

Figure 1.

Model to determine the objectives of patient education

Competing interests: None declared

Author: Chris Feudtner is a pediatrician and health services researcher who focuses on children with complex chronic conditions and their families.

References

- 1.Veldtman GR, Matley SL, Kendall L, et al. Illness understanding in children and adolescents with heart disease. Heart 2000;84: 395-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudre P, Jacquemet S, Uldry C, Perneger TV. Objectives, methods and content of patient education programmes for adults with asthma: systematic review of studies published between 1979 and 1998. Thorax 1999;54: 681-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glanz K, Rimer BK. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 1997. Available at: http://rex.nci.nih.gov/NCI_Pub_Interface/Theory_at_glance/HOME.html

- 4.Kenney RL. Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decisionmaking. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1992.

- 5.Bauman LJ, Drotar D, Leventhal JM, Perrin EC, Pless IB. A review of psychosocial interventions for children with chronic health conditions. Pediatrics 1997;100: 244-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]