This is the final article in our 4-part series on rural health. Previous articles were “Physicians and rural America” (November 2000, pp 348-351), “Hospitals in rural America” (December 2000, pp 418-422), and “Rural children's health” (February 2001, pp 142-147). All articles were adapted, with permission, from Ricketts III TC: Rural Health in the United States. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999.

The aging of Americans has dramatic implications for the health care system. About one fifth of the elderly population—defined as persons aged 65 years and older—lives in rural places, accounting for 8.2 million people in 1995. Although in the past, rural areas have had higher concentrations of older people, this trend appears to be changing.

Rural elders differ in several important respects from the stereotypical rural older person living in an idyllic home in a quaint country setting surrounded by a large multigenerational family. Compared with urban elders, rural elders have lower incomes, are more likely to be poor, and have less formal education.1 Although they are more likely to own their homes, those dwellings are more likely to be substandard. They are more likely to be in poorer health than their urban counterparts. Yet, their health and long-term care needs are less likely to be met owing to problems in the availability of health and social services and the obstacles to delivering services in rural areas, including low population densities, limited transportation, and longer travel distances.2

Patterns in the availability and use of health and long-term care services among rural elders suggest several important policy challenges. Federal and state efforts to shift the use of services away from costly institution-based care in hospitals and nursing homes will be particularly difficult to achieve in rural areas. The rural system of long-term care service is characterized by a larger supply (per elder) of nursing home beds than in urban areas and fewer community-based, in-home service, and residential care options. These factors may contribute to the higher-than-usual rates of institutional service use among rural elders.

Changes in federal and state policies, consumer preferences, and other factors are transforming the landscape of our long-term care system (see box). Whether and how these trends are affecting rural elders and the health and long-term care systems that serve them remain important questions.

Table 1.

| Changes in the landscape of the US long-term care system |

|---|

|

In this article, we compare the demographic and health characteristics of rural and urban elders, assessing important differences in the availability and use of health and long-term care services. We discuss the implications of these in the context of the changing environments of health and long-term care policy and identify barriers to improving the rural long-term care system.

RURAL ELDERS

Population trends

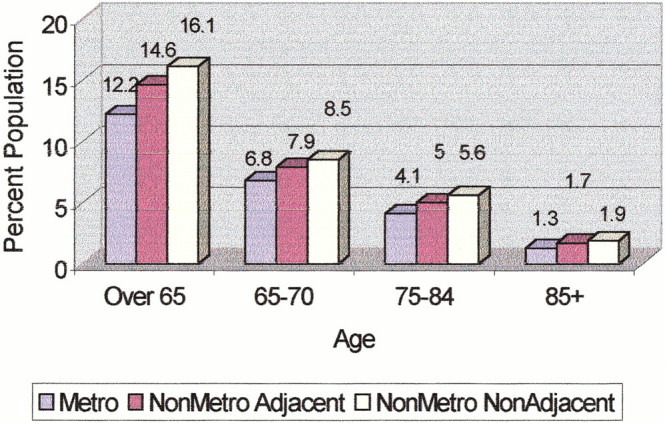

In general, rural areas have had a higher proportion of persons aged 65 and older than urban areas. In 1995, elderly persons comprised 14.6% of the population in nonmetropolitan counties compared with 12.2% in metropolitan counties (figure 1).3

Figure 1.

Age distribution of rural and urban residents aged 65 years and older, 1996. Residence is defined by urban influence codes (see Gelfi and Parker3). From the Bureau of Census, Department of Commerce.

Consistent with national trends, the elderly population has been growing in rural counties since the 1960s. Growth rates for the elderly population were higher in nonmetropolitan counties during the 1980-1990 period than in metropolitan counties. Recent estimates, however, show a reversal for the period 1990-1995, with a declining elderly growth rate in nonmetropolitan counties. Analyses by Fuguitt and colleagues suggest that this “deconcentration” of the elderly in rural areas is due to 2 primary factors: an increase in the immigration of younger persons into nonmetropolitan counties and the simultaneous emigration of the elderly population away from rural areas.4

The proportion of elders residing in nonmetropolitan counties and population growth rates in this age cohort show substantial regional differences. Specifically, the concentration of older persons in nonmetropolitan counties is greater in the Midwest and the South than in the West and the Northeast.5

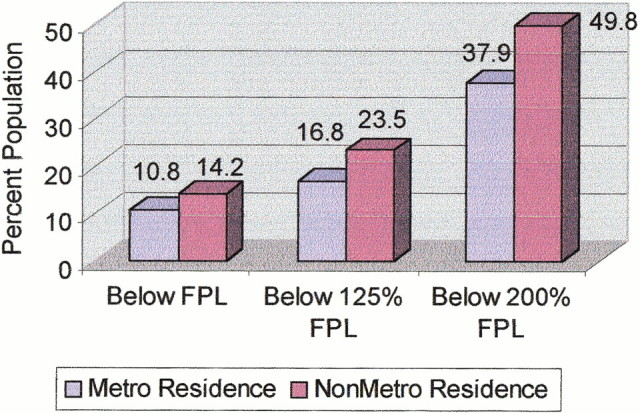

Income and poverty

Elderly residents of nonmetropolitan counties have lower incomes and are more likely to be classified as “poor” or “low income” than older persons residing in metropolitan areas. Lower incomes among rural elders are attributable to a variety of factors (see box).2

Data from 1995 indicate that 14.2% of elderly residents of nonmetropolitan counties were classified as “poor,” with incomes below the federally designated poverty level ($7,309); 10.8% of the metropolitan elders were so classified (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Income of rural and urban elderly residents (≥65 years old), 1995. FPL=federally designated poverty level.

Data from the Social Security Administration indicate that rural elders receive lower average monthly Social Security benefits than those living in urban locations. This reflects the lower incomes and lifetime earnings of rural people before retirement.2 Moreover, rural elders—poor and nonpoor—receive a higher proportion of their income from Social Security.

Living arrangements and housing

The living arrangements of elderly persons in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties do not differ much. Whereas rural elders are more likely to own their homes, free of any mortgage, those homes tend to be of lower value and in poorer condition than those of urban elderly residents.5

HEALTH AND FUNCTIONAL STATUS OF RURAL ELDERS

Health status and functional limitations

Despite the stereotype of the hale-and-hardy older rural person, a higher proportion of rural elders rate their health as fair or poor. This global measure of health status is usually considered critical because it is associated with mortality, quality of life, and other important measures of health status. Analyses of the National Health Interview Survey (1990-1994) indicate that rural elders, and especially those living in the most remote rural places, are more likely to rate their health as “fair” or “poor.” Older persons living in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas vary considerably by geographic location. In general, farm-residing elders are more likely to be in better health than their nonfarm-living counterparts.6 A higher proportion of elders in nonmetropolitan counties than in metropolitan counties report a functional status problem.

Table 2.

| Factors leading to lower incomes in rural elders |

|---|

|

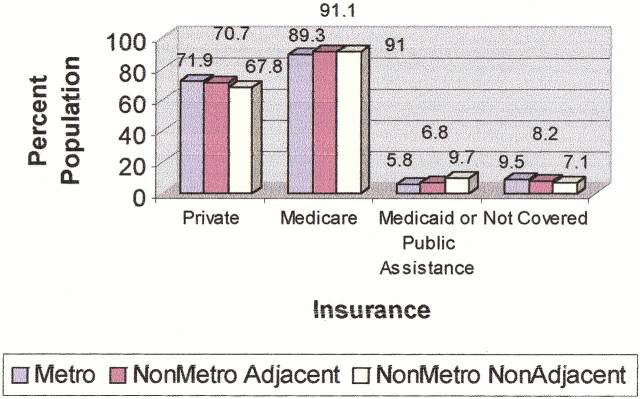

Health insurance coverage

In general, elders living in nonmetropolitan counties rely more heavily on Medicare and Medicaid programs and are less likely to have supplemental, private insurance coverage than those living in metropolitan counties (figure 3). The proportion of elders with supplemental private insurance coverage is lower in nonmetropolitan areas and especially those not adjacent to a metropolitan area.

Figure 3.

Percentage of persons aged 65 and older by medical insurance coverage and residence, United States, 1994 (from the 1994 Health Insurance Questionnaire of the National Health Interview Survey). Categories of insurance coverage may not be mutually exclusive because many persons have double coverage. Percentages are based on weight counts.

Not surprisingly, given their lower incomes and higher participation rates in the Supplemental Security Income Program, rural elders are more likely to receive Medicaid or public assistance than their urban counterparts. Nearly 10% of older persons living in nonmetropolitan areas not adjacent to a metropolitan area are receiving Medicaid or other public assistance. This compares with 5.8% of elders living in metropolitan areas.

Health care access and use of health services

The more limited availability and accessibility of health professionals and services in rural areas are among the most-recognized barriers to the appropriate use of health services among rural people. These and other access barriers, especially the lack of affordable and available transportation, limited income, and health insurance coverage, are critical for rural elders who face additional problems with physical frailty and the lack of social support.

Physician services

Data from the 1990-1994 National Health Interview Survey do not indicate a consistent pattern of differences across geographic areas in the average number of physician visits per person in the past year. Among elders aged 65 to 69 years, visit rates were lowest among rural elders living in nonmetropolitan areas adjacent to a metropolitan area. In contrast, among elders aged 70 to 74 years, physician visit rates were lowest among elders living in nonmetropolitan areas of less than 2,500 population. Interestingly, rural elders aged 75 years and older had similar or higher physician visit rates than urban elders in this same age cohort.

Not surprisingly, rural elders are more likely than those in urban areas to have to travel more than 30 minutes to obtain services; they are also more likely to have to wait more than 30 minutes at the site of care for their appointments.5

Hospital use

On average, rural elders have rates of hospitalization similar to or higher than those living in urban areas.

THE RURAL LONG-TERM CARE SYSTEM

Most elderly persons rely on their spouses, children, family members, or informal support networks to help them with their financial, household, and other needs. Only a few older persons use formal, paid health and social support services (eg, home health services). Understanding the family and social support characteristics of rural and urban elders is critical, therefore, to understanding differences that may exist in their long-term care needs.

Table 3.

| Differences between nursing homes in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas |

|---|

|

A body of literature suggests that rural elders are less likely than those living in urban places to use formal, in-home long-term care services.6,7,8 This phenomenon is usually attributed to the more limited availability and accessibility of formal services in rural communities. Moreover, among those using services, substantial differences exist among rural and urban elders in the mix of services used. On the one hand, studies have shown a higher use of nursing home services (especially custodial level care) among rural elders and lower rates of home health and other community-based, in-home services.9,10 The larger supply of nursing homes in rural areas, combined with the more limited availability of community-based, in-home services, are often suggested as reasons for these higher rates of nursing home use.11

Federal and state policies continue to encourage shifts away from costly institution-based care in hospitals and nursing homes to community-based, in-home services. The effects of these policies in rural areas, and especially those dominated by the availability and use of nursing homes as the primary source of long-term care services, may be significant.

Nursing homes

According to the most recent data from the Nursing Home Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey conducted in 1996, the supply of nursing homes and nursing home beds is nearly 43% greater in nonmetropolitan than in metropolitan areas.12 Other differences between nursing homes in rural versus metropolitan areas are shown in the box.9,12 Rates of institutionalization are somewhat higher among the rural elderly population.

Using data from the Longitudinal Study on Aging (1984-1990), Coward and colleagues have shown that a higher percentage of residents of both urbanized and less urbanized, nonmetropolitan counties were admitted to a nursing home at higher rates than those living in a metropolitan county.13 Although this study provides strong evidence that rural elders are at greater risk than urban elders of entering a nursing home in their life, the authors were unable to account fully for the differences using the usual factors that predict nursing home use, such as sociodemographic and health characteristics of the population. They speculate that the supply of long-term care services, the attitudes of rural elders toward nursing homes, and other factors may be important determinants of their higher rates of nursing home use.

Use of home health and other formal services

Evidence shows that rural Medicare beneficiaries have lower rates of home health use than urban beneficiaries. The difference between the rural and urban rates has been narrowing. The number of visits per beneficiary is higher among rural Medicare enrollees than among urban enrollees. The type of services used by rural and urban beneficiaries varies, however. Among those who use Medicare home health services, rural users are more likely to use skilled nursing and home health aide services; in contrast, urban users have higher rates of use for therapy and medical social service visits.

CONCLUSIONS

Two particularly important barriers and challenges exist to reducing the differences in health and long-term care access and use for older persons. First, the current financing of long-term care generally, and in rural areas in particular, limits the availability of services (and, therefore, their use) in rural areas. With a more limited capacity to pay for long-term care services out of their own pockets, rural elders are more dependent on Medicare, Medicaid, and other public programs for funding to meet their long-term care needs. Yet, as evidenced in recent provisions in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, reducing Medicare expenditures following acute care, continuing pressures on public programs may limit access to critical services for older people living in rural communities.

A second challenge will be to develop better models for delivering health and long-term care services in rural communities. This problem is especially important in light of the limited financing for long-term care and the competition for health personnel. Innovative financing and delivery models are needed in rural areas to provide the necessary incentives for service expansion and integration among acute and long-term care providers. Achieving this objective is critical for developing a more adequate system of long-term care service to meet the needs of older people in rural communities.

Summary points

About a fifth of elderly persons—those aged 65 years and older—in the United States live in rural places

Elderly residents of rural areas are more likely than those of urban areas to be classified as “poor” or “low income”

Self-rated health, which is associated with mortality and quality of life, is worse in elderly living in rural areas than in those in urban areas

Well-documented deficiencies exist in the availability and accessibility of health and long-term care services to rural elderly

2 key barriers need to be overcome to address these deficiencies: the current financing of long-term care in general, and the need for better models for delivering services in rural communities

Figure 5.

Understanding the family and social support characteristics of rural and urban elders is critical

National Archives and Records Administration/Visual Image Presentations

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Coward RT, McLaughlin D, Duncan RP. An overview of health and aging in rural America. Chap 1. In: Coward RT, Bull CN, Kukulka G, Galliher JM, eds. Health Services for Rural Elders. New York: Springer Publishing; 1994.

- 2.Krout J. An overview of older rural populations and community-based services. Chap 1. In: Providing Community-Based Services to the Rural Elderly. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994.

- 3.Gelfi LM, Parker TS. A County-Level Measure of Urban Influence. US Dept of Agriculture, Rural Economy Division, Economic Research Service; 1997. ERS staff paper no. 9701.

- 4.Fuguitt G, Gibson R, Beale C, Tordella S. Elderly Population Change in Nonmetropolitan Areas: From the Turnaround to the Rebound. Paper presented at Western Regional Science Association annual meeting, Monterey, CA, 1998.

- 5.Van Nostrand JF, ed. Common beliefs about the rural elderly: what do national data tell us? Vital Health Stat 3 1993, no. 28. [PubMed]

- 6.Coward RT, Cutler SJ. Informal and formal health care systems for the rural elderly. Health Serv Res 1989;23: 785-806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenney GM. Rural and urban differentials in Medicare home health use. Health Care Financ Rev 1993;14: 39-57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenney GM. Is access to home health care a problem in rural areas? Am J Public Health 1993;83: 412-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaughnessy PW. Changing institutional long term care to improve rural health care. In: Coward RT, Bull CN, Kukulka G, Galliher JM, (eds). Health Services for Rural Elders. New York: Springer Publishing; 1994: 144-181.

- 10.Coward RT, Horne C, Peek CW. Predicting nursing home admissions among incontinent older adults: a comparison of residential differences across six years. Gerontologist 1995;35: 732-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene VL. Premature institutionalization among the rural elderly in Arizona. Public Health Rep 1984;99: 58-63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhoades J, Potter D, Krause N. Nursing Homes: Structure and Selected Characteristics, 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Research Findings no. 4. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1998. AHCPR publication 98-0006.

- 13.Coward RT, Netzer JK, Mullens RA. Residential differences in the incidence of nursing home admissions across a six-year period. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc 1996;51: S258-S267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]