Abstract

A mutant (JY2190) of Streptococcus pneumoniae Rx1 which had acquired the ability to grow in the absence of choline and analogs was isolated. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and wall teichoic acid (TA) isolated from the mutant were free of phosphocholine and other phosphorylated amino alcohols. Both polymers showed an unaltered chain structure and, in the case of LTA, an unchanged glycolipid anchor. The cell wall composition was also not altered except that, due to the lack of phosphocholine, the phosphate content of cell walls was half that of the parent strain. Isolated cell walls of the mutant were resistant to hydrolysis by pneumococcal autolysin (N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase) but were cleaved by the muramidases CPL and cellosyl. The lack of active autolysin in the mutant cells became apparent by impaired cell separation at the end of cell division and by resistance against stationary-phase and penicillin-induced lysis. As a result of the absence of choline in the LTA, pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) was no longer retained on the cytoplasmic membrane. During growth in the presence of choline, which was incorporated as phosphocholine into LTA and TA, the mutant cells separated normally, did not release PspA, and became penicillin sensitive. However, even under these conditions, they did not lyse in the stationary phase, and they showed poor reactivity with antibody to phosphocholine and an increased release of C-polysaccharide from the cell. In contrast to ethanolamine-grown parent cells (A. Tomasz, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 59:86–93, 1968), the choline-free mutant cells retained the capability to undergo genetic transformation but, compared to Rx1, with lower frequency and at an earlier stage of growth. The properties of the mutant could be transferred to the parent strain by DNA of the mutant.

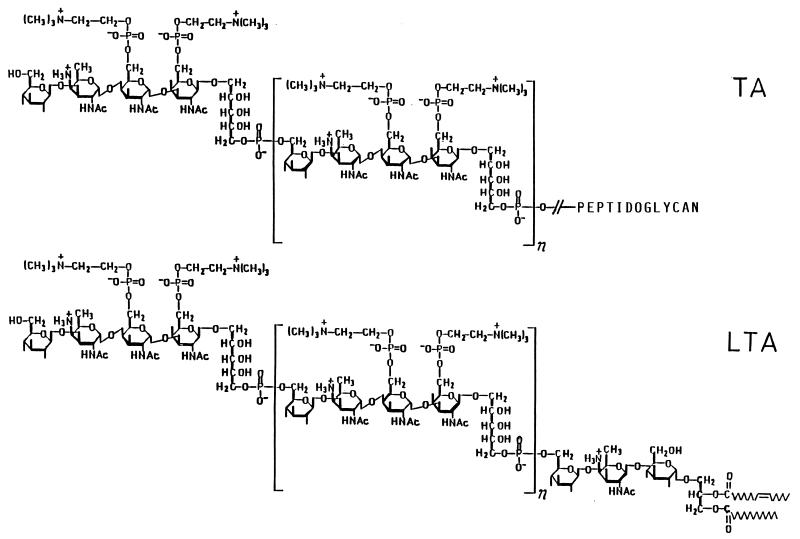

Pneumococci differ from other gram-positive bacteria in that their lipoteichoic acid (LTA) and wall teichoic acid (TA) have the same chain structure which is, moreover, unusually complex (Fig. 1): glycerophosphate is replaced by ribitol phosphate (7), and between the ribitol phosphate residues a tetrasaccharide is intercalated (23). It contains d-glucose, 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-galactose (AATGal), and two N-acetyl-d-galactosaminyl residues, one or both of which carry a phosphocholine residue at O-6 (references 3 and 12 and this report).

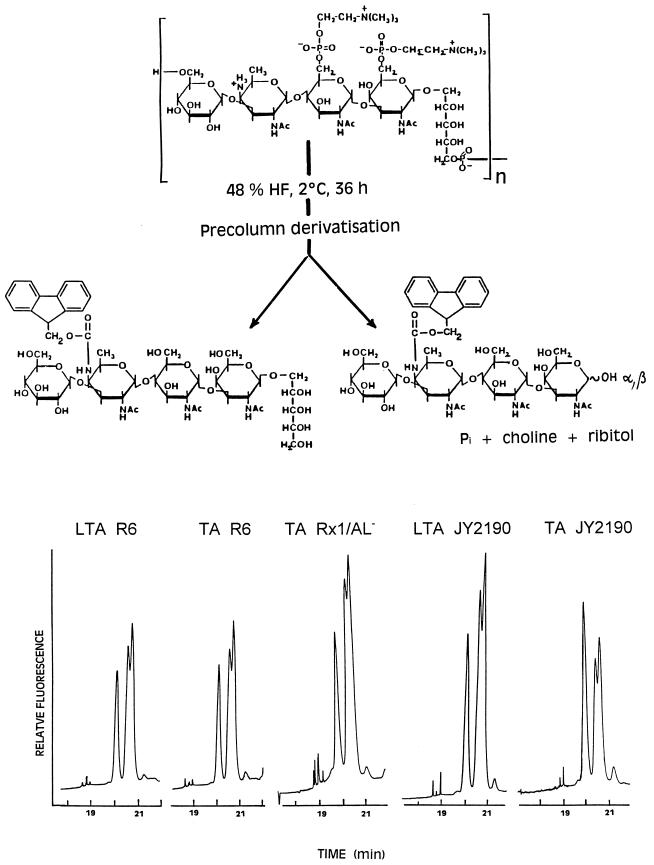

FIG. 1.

Pneumococcal TA and LTA. As shown, in strain R6 most of the repeats carry two phosphocholine residues each, at O-6 of the N-acetyl-d-galactosaminyl residues (3, 12). In strain Rx1 and Rx1/AL−, most repeats contain one phosphocholine residue (this report) attached to O-6 of the non-ribitol-linked galactosaminyl residue (14).

Pneumococci are not able to synthesize the choline required for the synthesis of these substituents. Moreover, choline is an essential growth factor (2, 30) but can be substituted in this function by nutritional ethanolamine (EA) (38). Phosphoethanolamine is incorporated into LTA and TA in place of phosphocholine (14), but it cannot replace phosphocholine functionally. Phosphocholine-substituted LTA serves to anchor pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) to the outer layer of the cytoplasmic membrane, with choline-mediated interaction between membrane-associated LTA and the C-terminal repeat region of PspA. In EA-grown bacteria, PspA is no longer retained and is released into the surrounding medium (45). Phosphocholine substituents also play an essential role for the activity of the major pneumococcal autolysin, an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase (38). This protein possesses a choline-binding C-terminal domain that is essential for activity but, unlike PspA, is not essential for retention on the pneumococcal cell surface (16, 32). Binding of phosphocholine-substituted LTA to this domain results in potent inhibition of the amidase (21). The inhibitory property is dependent on the micellar structure of LTA (13) and lost by deacylation (5). Phosphocholine-substituted LTA may also participate in the transport of the amidase through the cytoplasmic membrane from the cytosol (5), the location of its synthesis (15). It additionally effects the conversion of the inactive E form of the enzyme into the active C form (5). This conversion is likewise effected by the choline residues of cell wall-linked TA (33, 39). Furthermore, binding of the amidase to the choline residues of TA is prerequisite for the hydrolysis of cell walls by the enzyme (18, 22). It should be noted that the amidase is not essential for growth. Though the enzyme is completely inactive in EA grown cells, the growth rate is not affected. However, cell separation is impaired, and there is a loss of stationary-phase and penicillin-induced cell lysis (38, 40), as well as a loss of genetic transformation (38). After insertional inactivation of the autolysin gene (lytA), the autolysin-deficient mutants (Lyt−) grew normally (31) and did not even show impeded cell separation (41).

In this report, we describe a mutant which acquired the ability to grow in the absence of choline and analogs. Except for the observation that [3H]choline-substituted LTA is not a precursor of [3H]choline-substituted TA (6), nothing is known about the biosyntheses of pneumococcal LTA and TA and the stage of biosynthesis at which phosphocholine is incorporated. Since the absence of choline incorporation might affect the structure of LTA and TA as well as the composition of cell walls, we included relevant analyses in our study.

(A preliminary report of this work was presented in an overview on pneumococcal LTA and TA at the International Meeting on the Molecular Biology of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Its Diseases, Oeiras, Portugal, September 24 to 29, 1996 [10].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

CPL, a muramidase from the pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 (17), and pneumococcal N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase (15, 33), purified as described in the references cited, were provided by Ernesto Garcia (Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Madrid, Spain). Cellosyl from Streptomyces coelicolor was provided by Stefan Müllner (Höchst AG, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Other enzymes and coenzymes were from Boehringer Mannheim GmbH (Mannheim, Germany) or Sigma-Aldrich Chemie (Deisenhofen, Germany). LTA- and TA-containing cell walls of S. pneumoniae R6 were from previous work (3, 12). Muramic acid-6-phosphate was prepared from Staphylococcus aureus cell walls as described elsewhere (25).

Bacterial strains, growth, and transformation.

S. pneumoniae Rx1 (36) and its derivative JY2190 were grown at 37°C in either chemically defined medium (CDM) (42), prepared by JRH Biosciences (Denver, Pa.), or Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (THY; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or on blood agar base no. 2 (BAP; Difco) containing 3% sheep blood. Where indicated, CDM was supplemented with EA (0.02%) or choline (0.0005%). For chemical analyses of the parent Rx1, the nonlytic derivative Rx1/AL− (4), provided by James Paton (Adelaide Children’s Hospital, North Adelaide, South Australia, Australia), was grown at 37°C in a complex medium (10 g of meat extract, 20 g of casein peptone, 5 g of yeast extract, 2 g of NaCl, 2 g of K2HPO4, 4 g of glucose, 1 liter of H2O). Bacteria were stored as frozen stocks at −85°C in growth medium containing 10% glycerol. Transformation of S. pneumoniae was performed as previously described (43). DNA was obtained by phenol-chloroform extraction when the mutant strain was grown in CDM or by standard deoxycholate lysis (43) when it was grown in choline-containing medium. Rx1 recipients transformed by JY2190 DNA were initially selected for by the ability to grow in liquid CDM lacking choline. Isolated colonies obtained from samples plated on blood agar medium were then tested for the ability to grow in the absence of choline.

Immunoblot analyses.

For immunodot blot analyses of PspA and autolysin, cell lysates and culture supernatant fluids (clarified through 0.45-μm-pore-size low-protein-binding filters) were prepared as previously described (44, 45). Samples from mid-exponential-phase cultures grown to equivalent optical densities (ODs) were spotted on a nitrocellulose membrane and developed as previously described for Western blots (44, 45). Equivalent amounts of all samples, representing 1 μl of unconcentrated culture, were examined. Monoclonal antibodies Xi136 (PspA specific [26]) and 140.1C2 (phosphocholine specific) were provided by David Briles (University of Alabama at Birmingham). Autolysin-specific polyclonal antiserum (4) was provided by James Paton.

Microscopy.

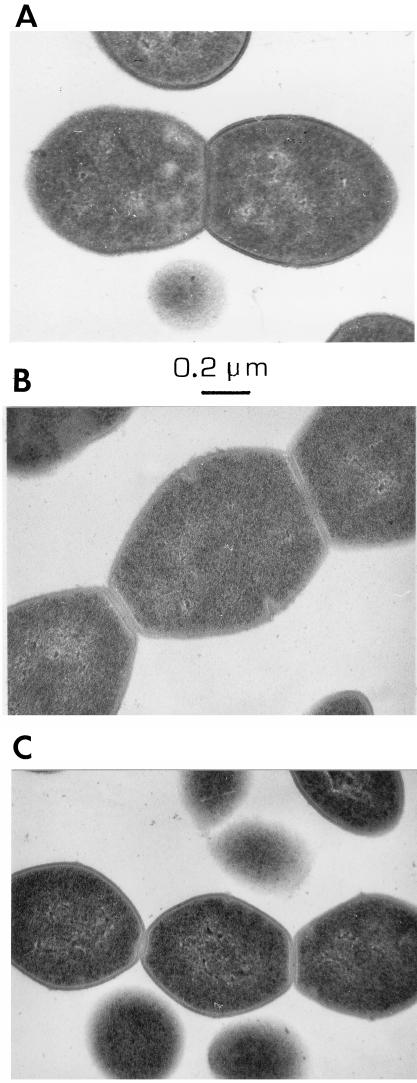

Bacteria, grown to mid-exponential phase in the indicated media, were observed under phase contrast. Photomicrographs represent a final magnification of ×862. For electron microscopy, samples were centrifuged, washed once in 1/20 volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in 1/20 volume of 1% glutaraldehyde–PBS, and then resuspended in 1/5 volume of PBS. Electron micrographs represent a final magnification of ×50,000.

Extraction and purification of LTA and cell walls.

LTA was extracted from late-exponential-phase bacteria as described previously (3) except that the bacteria were disintegrated with glass beads in a Braun disintegrator (11). Briefly, LTA and lipids were extracted from broken cells with a Bligh-Dyer monophasic system and separated from cell walls by centrifugation. To the supernatant fluid, CHCl3 and H2O were added to achieve phase separation. The methanol-H2O layer was dialyzed, freeze-dried, and for purification of LTA, subjected to hydrophobic interaction chromatography on octyl-Sepharose (3). For analysis of TA, cell walls were prepared from disintegrated bacteria and purified as previously described (20) by hot sodium dodecyl sulfate extraction, digestion with nucleases and trypsin, a second sodium dodecyl sulfate extraction, and several washing steps, including one in 5.8 M LiCl. After washing with H2O, cell walls were freeze-dried.

Analytical procedures.

Carbohydrate (28), choline (1), d-glucose (24), glycerol (27), hexosamine (37), periodate (8), formic acid (34), and phosphate (35) were measured as described in each reference. Ribitol and anhydroribitol were quantified as acetates by gas-liquid chromatography (internal standard, mannitol) (3). Galactosamine, glucosamine, muramic acid, muramitol, quinovosamine, and EA were identified and quantified (internal standard, taurine) as fluorescent fluoren-9-yl-methoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) derivatives by reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (12). Tetrasaccharide ribitol and the anomeric forms of the tetrasaccharide released by HF from pneumococcal LTAs and TAs (see below) were separated as Fmoc derivatives by reverse-phase HPLC using the recently described elution program (12) with a modified flow rate (1 ml/min).

For compositional analysis, LTA and cell wall-linked TA were N-acetylated (29) and dephosphorylated with 48% (by mass) aqueous HF (2°C, 36 h), and after drying over KOH in vacuo, the hydrolysis products were taken up in 0.1 M lithium acetate (pH 4.7). For TA analysis, cell walls were removed by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 10 min), and the supernatant fluid was used. Choline and phosphate were measured directly; amino sugar components and ribitol were measured after additional hydrolysis in 4 M HCl (100°C, 4 h). Galactosamine was quantified by an Elson-Morgan procedure (37). Glucose, which is released incompletely by HCl (3), was identified enzymatically (24) and quantified by an anthrone procedure (28). Amino acids were released and quantified by reverse-phase HPLC as described previously (19). Muramic acid-phosphate of cell walls was determined as the difference between muramic acid measured after hydrolysis with HCl and subsequent hydrolysis with HF.

Glyceroglycolipids, released from LTAs with 48% (by mass) HF as described previously (3), were analyzed before and after N-acetylation by thin-layer chromatography on silica gel plates (Merck 60) with CHCl3-methanol-H2O (65:25:4, by volume) as the solvent and stained with 1-naphthol–H2SO4. For identification of the deacylation products, propanol–25% (by mass) NH4OH–H2O (6:3:1, by volume) was used as the solvent.

Periodate oxidation.

Cell walls from the mutant strain were solubilized by treatment with cellosyl (see below), and the phosphate-containing products were isolated by column chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex A-25 which was eluted with water, followed by a linear gradient of 0 to 0.3 M NH4HCO3 (pH 8.2). After desalting by passage through a column of Sephadex G-15, the phosphate-containing products (20 μmol of phosphate) were oxidized in 0.2 M NaIO4 (1.55 ml) containing 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.7) at room temperature in the dark. The oxidation was monitored photometrically (8).

Amidase activity.

The activity of pneumococcal amidase was assayed in a standard mixture consisting of 1.5 mg of cell wall (0.5 μmol of N-acetylmuramic acid) and 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0) containing 0.04% NaN3 (1 ml). The arbitrary unit was v0 = 0.3 (ΔE578 · min−1).

RESULTS

Generation and initial characterization of the mutant strain.

Mutant JY2190 was isolated by serial passage of strain Rx1 in CDM containing decreasing concentrations of EA with each passage. Initially, approximately 106 Rx1 cells were inoculated into 2 ml of CDM containing 200 μg of EA/ml, and the culture was grown for 12 h at 37°C and then diluted 100-fold into CDM containing the same concentration of EA. Following five 12-h passages in CDM containing 200 μg of EA/ml, similar passages were performed in successively lower concentrations of EA, i.e., 20, 2, 0.2, and then 0 μg/ml. The mutant obtained in this manner was capable of growth in CDM without added choline, EA, or other choline analogs, whereas the parent Rx1 was not.

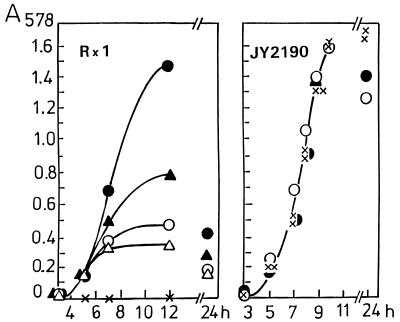

Figure 2 shows the growth of the mutant in comparison with the parent strain. The latter, when grown in CDM containing limited concentrations of choline (0.5 to 2.0 μg/ml), stopped growing when the available amount of choline was consumed. The OD of the Rx1 culture was drastically reduced after 24 h, indicating that lysis had occurred in the stationary phase. In contrast, the growth curve of the mutant strain was not affected, whether choline was absent or present at various concentrations. After growth in the absence of choline, there was no autolysis in the stationary phase. Even after growth in the presence of choline, there was unexpectedly little lysis. Lysis of choline-grown cells could be triggered, however, by the addition of 0.1% deoxycholate. Without stirring, cells grown in liquid culture settled to the bottom of the culturing vessel, resulting in a nearly clear supernatant solution.

FIG. 2.

Growth of parent strain Rx1 and mutant JY2190 in CDM containing no choline (x) or choline at a concentration of 5 μg/ml (•), 2 μg/ml (▴), 1 μg/ml (○), or 0.5 μg/ml (▵).

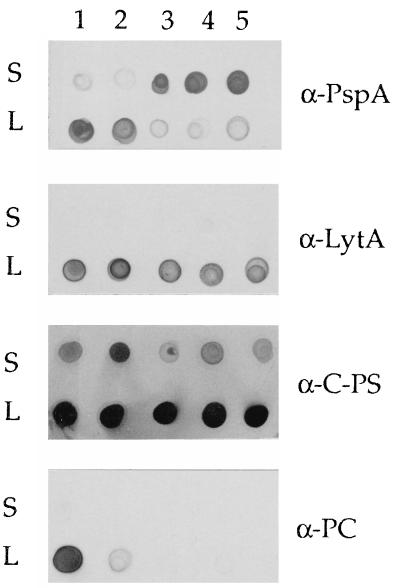

Attachment of PspA to the pneumococcal cell surface requires the presence of choline residues in the LTA. When EA is substituted for choline, PspA is released from the cell (45). Similarly, when mutant JY2190 was grown in the presence of choline, PspA remained cell associated. In the absence of choline or in the presence of EA, the majority of PspA was detected in culture supernatant fluids. In contrast, autolysin, which requires the choline residues for activity but not for attachment to the cell, remained cell associated under all growth conditions (Fig. 3). Immunoblotting also demonstrated reactivity of the mutant strain with antibodies specific for both C-polysaccharide (TA) and, when grown in choline-containing medium, phosphocholine. In the latter case, however, the mutant was very weakly reactive, in contrast to the parent strain (Fig. 3). In addition, in contrast to the parent strain, significant amounts of C-polysaccharide were released from the mutant strain when grown in the presence of choline (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Reactivity with S. pneumoniae-specific antibodies. Culture supernatants (S) and cell lysates (L) were reacted with antibodies specific for PspA, autolysin (LytA), C-polysaccharide (C-PS), and phosphocholine (PC). Bacteria were grown in CDM containing choline (5 μg/ml), EA (200 μg/ml), or no analog, as indicated. Lanes: 1, Rx1 plus choline; 2, JY2190 plus choline; 3, JY2190, no choline or analogs; 4, Rx1 plus EA; 5, JY2190 plus EA.

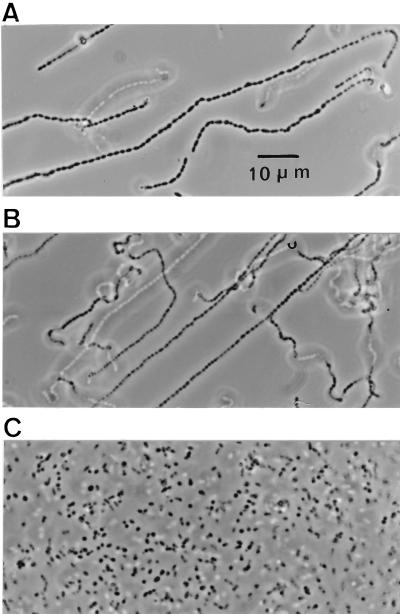

Photomicrographs of the mutant strain grown under various conditions are shown in Fig. 4. Growth either in the absence of choline or in the presence of EA (200 μg/ml) resulted in the formation of long chains of >100 cells. Cells grown in the absence of choline appeared to be somewhat larger than the EA-grown cells. When the mutant strain was grown at low concentrations of choline (5 μg/ml), cell separation was normal, as indicated by the formation of diplococci and short chains. Electron microscopy revealed incomplete septation in mutant JY2190 when it was grown either in the absence of choline or in EA. Although the cells were larger when grown in the absence of choline, they otherwise appeared normal and were indistinguishable from those of the parent Rx1 when cultured in the presence of choline (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Photomicrographs of JY2190 grown in CDM. Cultures were grown in the absence of choline or analogs (A), the presence of EA (200 μg/ml) (B), and the presence of a low concentration (5 μg/ml) of choline (C).

FIG. 5.

Electron micrographs of Rx1 and JY2190 grown in CDM plus choline or EA. (A) Rx1 plus choline (5 μg/ml) (JY2190 appeared identical and is not shown); (B) JY2190 with no choline or analogs; (C) JY2190 plus EA (200 μg/ml).

When DNA extracted from mutant JY2190 was used to transform the parent Rx1, all of the mutant properties were transferred to the recipient isolates (data not shown). In these experiments, transformants were selected by using liquid rather than solid CDM medium because of the presence of choline in standard agar preparations. Thus, it was not possible to determine a transformation frequency, and we do not know at this time whether more than one mutation is involved in the phenotype.

Isolation and analysis of LTA and TA.

Estimates of phosphate in the cell fractions of JY2190 and Rx1/AL− suggested that the cellular contents of LTA and TA were similar and that LTA and TA were present in ratios between 0.06:1 and 0.2:1, respectively.

Table 1 shows the compositions of LTA and TA from the mutant and parent strains in comparison with the data for R6 (3, 12). Both polymers uniformly contained 1 mol equivalent of both glucose and ribitol, and 2 mol equivalents of galactosamine per intrachain phosphate. The presence of quinovosamine, resulting from deamination with HNO2, is indicative of 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxygalactose as another component (3). No choline was detected in LTA and TA when the mutant was grown in CDM. Reproducible choline/total phosphate ratios of 0.64 ± 0.01 were found in separate LTA and TA preparations from R6, and choline/total phosphate ratios of 0.54 ± 0.01 were observed in LTA and TA preparations from Rx1/AL− and Rx1.

TABLE 1.

Compositions of the LTAs and TAs from S. pneumoniae JY2190, Rx1/AL−, and R6a

| Component | Molar ratio to intrachain phosphate (total phosphate − choline-linked phosphate)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JY 2190

|

Rx1/AL−

|

R6

|

||||

| TA | LTA | TA | LTA | TA | LTA | |

| Total phosphate | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.17 | 2.13 | 2.86 | 2.78 |

| Choline | 0 | 0 | 1.17 | 1.13 | 1.86 | 1.78 |

| Intrachain phosphate | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Glucose | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 0.89 | 1.01 |

| Galactosamine | 1.90 | 1.95 | 2.13 | 2.20 | 2.00 | 1.98 |

| Ribitolb | 1.10 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.00 | |

| Quinovosaminec | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Glycerold | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.16 | |||

JY2190 was grown in CDM lacking choline or analogs. Rx1/AL− and R6 were grown in choline-containing medium.

Ribitol plus 2,5-anhydroribitol.

Indicative of 2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxygalactose (see text).

Released from the glyceroglycolipid anchor of LTA (see text).

The ability of the mutant to grow in the absence of choline could have two alternative causes: either the mutant acquired the capability to produce EA from serine, or it became independent of choline and analogs for growth. We therefore used the recently described reverse-phase HPLC procedure (12) to examine HF hydrolysates of LTA and TA of JY2190 for EA. The negative result allows us to definitely rule out the presence of EA because EA was readily detected in the HF hydrolysate of cell walls from Rx1/AL− grown in CDM containing EA (200 mg/l).

Fingerprint identification of the repeat.

In LTA and TA, the glycosidic bond of the β-N-acetylgalactosaminyl residue to the ribitol moiety proved extraordinarily susceptible to acid hydrolysis (3, 12, 23), so that depending on the duration of hydrolysis with HF, increasing amounts of the reducing tetrasaccharide and equimolar amounts of ribitol were formed. In this work, we took advantage of this acid lability for a fingerprint identification of the repeats (Fig. 6). The HF hydrolysis products were labeled by precolumn derivatization with 9-fluorenylmethyl-chloroformate at the 4-amino group of the AATGal residue, and the Fmoc derivatives were separated by reverse-phase HPLC. The teichoic acids tested displayed the same fingerprint pattern, which, together with the identical compositions given in Table 1, suggests that all of them contain the same tetrasaccharide ribitol repeat unit. That the sugar sequence, the anomeric bonds, and the glycosidic substitutions are actually identical was shown by nuclear magnetic resonance, fast atom bombardment-mass spectroscopy (MS), and MS-MS analyses (14).

FIG. 6.

Hydrolysis of the chains of various LTAs and TAs with HF and identification as Fmoc derivatives by reverse-phase HPLC of the released tetrasaccharide ribitol (single peak) and the anomeric forms of the concomitantly released α,β-tetrasaccharide (double peak).

Connection of the repeats.

Nonsubstituted TA-containing cell walls from the mutant were hydrolyzed with cellosyl, a muramidase, in order to obtain low-Mr products. The released TA-containing muropeptides were separated from nonsubstituted muropeptides by column chromatography on DEAE–Sephadex A-25 (not shown) and after desalting oxidized with periodate. Although by cleavage with cellosyl oxidizable N-acetylglucosaminyl residues are formed, their contribution to periodate consumption was estimated to be less than 10%. After complete oxidation (6 h), 4.3 mol of IO4− had been consumed per mol of repeat phosphate, with the concomitant formation of 1.9 mol of formic acid. Since formic acid can arise only from C-3 of a nonsubstituted or O-6-substituted hexopyranosyl moiety and from C-3 of a 1,5-substituted ribitol moiety, these results show that, like in LTA and TA of strain R6, the repeats are connected by phosphodiester bonds between O-5 of the ribitol moieties and O-6 of the adjacent glucosyl residues (Fig. 1). The consumption of 4 mol equivalents of periodate additionally provides evidence that the N-acetylgalactosaminyl residues are not oxidizable and therefore glycosidically substituted at O-4 and/or O-3.

Structure of the glyceroglycolipid anchor and number of repeats in LTA.

The glycolipid moieties of the LTA from the mutant and strain Rx1/AL− were isolated after hydrolysis by HF (3). On TLC, the native, N-acetylated, and deacylated forms displayed the same mobility as the respective forms of the glycolipid moiety of the LTA from S. pneumoniae R6 (data not shown). Moreover, the Fmoc derivatives of the deacylated glycolipids displayed identical retention times on reverse-phase HPLC. These observations suggest that in all three strains, the LTAs possess Glc(β1-3)AATGal(β1-3)Glc(α1-3)acyl2Gro as lipid anchor (Fig. 1). For chain length determination, the LTAs were deacylated (0.1 M NaOH, 37°C, 30 min), hydrolyzed in 2 M HCl (100°C, 2.5 h), and analyzed for glycerol. The number of repeats per glycolipid anchor, given by the molar ratio of intrachain phosphate to glycerol (Table 1), was approximately five for the LTA of the mutant, compared to seven and eight for the LTAs of strain Rx1/AL− and R6, respectively.

Cell wall composition.

As shown in Table 2, there was no significant difference between the cell walls of the mutant and strain Rx1/AL−. On a weight basis, the components of TA and peptidoglycan were present in essentially identical amounts. However, the phosphate content in the cell wall of the mutant was half that of strain Rx1/AL−, which reflects the nonsubstituted and phosphocholine-substituted repeats in the TA of these strains. The molar ratio of intrachain phosphate to muramic acid-6-phosphate suggests six and eight repeats per chain for the TAs from the mutant and Rx1/AL− strains, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Components of purified cell walls from the mutant JY2190 and strain Rx1/AL−a

| Component | Concn (μmol/mg [dry wt])

|

|

|---|---|---|

| JY2190 | Rx1/AL− | |

| Phosphate | 0.58 | 1.11 |

| Intrachain phosphate | 0.58 | 0.56 |

| Galactosamine | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| Glucose | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Ribitolb | 0.61 | 0.64 |

| Choline | 0 | 0.55 |

| Muramic acid | 0.38 | 0.34 |

| Muramic acid-6-phosphate | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Glucosamine | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| Glutamic acid | 0.54 | 0.52 |

| Serine | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Alanine | 0.83 | 0.85 |

| Lysine | 0.55 | 0.51 |

Cell walls were prepared from late-growth-phase cells. Both strains were grown in CDM, which in the case of Rx1/AL− was supplemented with choline (5 mg/liter).

Ribitol plus 2,5-anhydroribitol.

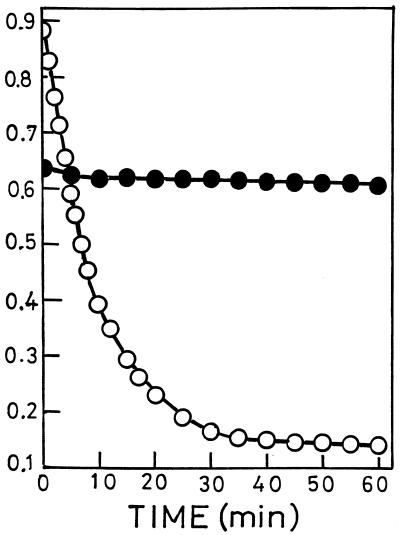

Behavior of cell wall hydrolases against phosphocholine-free cell walls.

N-Acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase, the major autolytic enzyme of pneumococci, requires phosphocholine residues in cell wall-linked TA for activity; cell walls containing phosphoethanolamine are not hydrolyzed (22). In accordance with this specific need, the cell walls of the mutant resisted cleavage by the amidase, whereas cell walls of strain Rx1/AL− were readily hydrolyzed (Fig. 7). After growth in the presence of choline, the cell walls of the mutant became susceptible to hydrolysis with the amidase, which solubilized more than 80% of the cell wall phosphorus (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Treatment of cell walls from mutant JY2190 (•) and strain Rx1/AL− (○) with pneumococcal N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase. Cell walls (1.5 mg in 1 ml of 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.0] containing 0.04% NaN3) were incubated at room temperature with amidase (•, 30 μg; ○, 3 μg). Hydrolysis was monitored by OD578. For preparation of cell walls, the bacteria were grown as indicated in Table 2, footnote a.

CPL, a muramidase produced by Cp-1, a bacteriophage specifically infecting pneumococci, was reported to require phosphocholine-substituted TA on the cell wall substrate for in vitro and in vivo activity and to be inactive when phosphocholine was biosynthetically replaced by phosphoethanolamine (17). However, the cell walls of the mutant strain were slowly hydrolyzed (Fig. 8A). Nevertheless, after incubation for 24 h, hydrolysis approached 70 to 80%, as measured by the decrease of OD at 578 nm (OD578) and the increase of solubilized phosphate, respectively (data not shown). Cellosyl, a muramidase from S. coelicolor, showed an inverse behavior: it hydrolyzed the cell walls of the mutant strain approximately twice as fast as those of strain Rx1/AL− (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Cleavage of cell walls from mutant JY2190 (•) and strain Rx1/AL− (○) with CPL (A) and cellosyl (B). Cell walls (4 mg) were incubated with CPL (22 μg) and cellosyl (32 μg) in 1 ml of 20 mM ammonium acetate (pH 6.0) at room temperature. Cleavage of the mutant cell walls (a) was accelerated by doubling the enzyme concentration (b). For overnight incubation, 0.05% (mass/vol) NaN3 was added. Hydrolysis was monitored by OD578. For preparation of cell walls, the bacteria were grown as indicated in Table 2, footnote a.

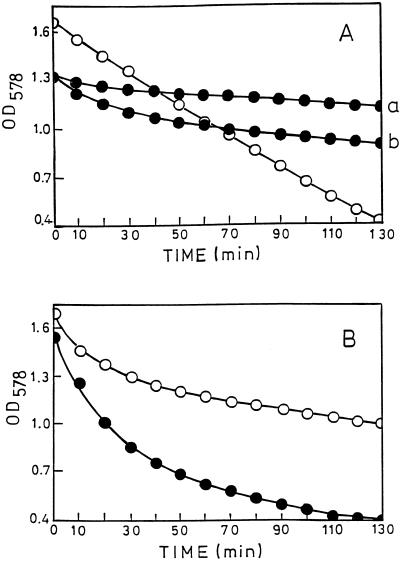

Penicillin tolerance of the mutant strain.

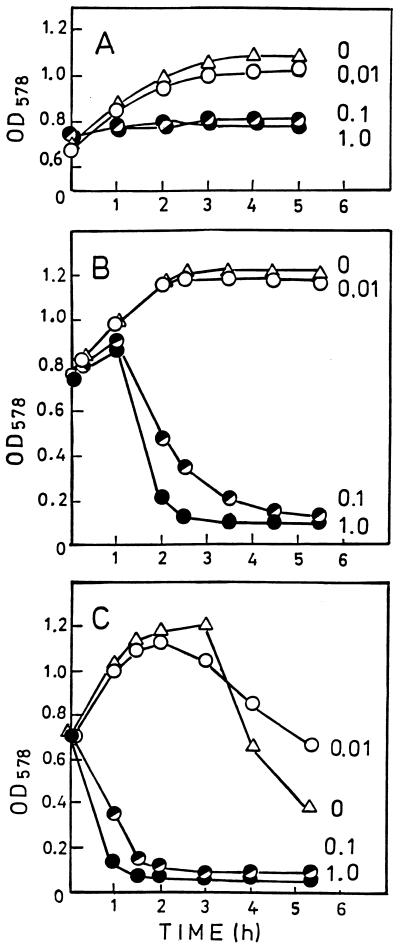

When cells of the mutant strain growing in CDM were treated with 0.01 μg of penicillin per ml during exponential growth phase, they continued growing at the same rate as the untreated control (Fig. 9A). At penicillin concentrations of 0.1 and 1.0 μg/ml, growth ceased but no lysis was seen. When, however, the mutant had been grown for 4 h in the presence of 0.1% choline before penicillin was added, antibiotic concentrations of 0.1 and 1.0 μg/ml led to cell lysis (Fig. 9B). The response to penicillin of the choline-grown mutant was the same as that of the parent strain (Fig. 9C): 0.01 μg of the antibiotic per ml did not affect the growth rate; 0.1 and 1.0 μg/ml evoked immediate cell lysis.

FIG. 9.

Response to penicillin of mutant JY2190 (A and B) and of parent strain Rx1 (C). Penicillin was added at time zero. Bacteria were grown in CDM in the absence of choline and analogs (A) and in the presence of 0.1% choline (B and C). Numbers on the graphs are penicillin concentrations (micrograms/milliliter). Growth and lysis were monitored by OD578.

The lack of penicillin-induced lysis of the mutant is consistent with the inability of the autolytic enzyme to attack in vitro the cell walls of the mutant (Fig. 7). Unexpectedly, the choline-grown mutant cells showed no stationary-phase lysis when penicillin was omitted or added in low concentration (0.01 μg/ml) (Fig. 9B). Even after incubation for 24 h, no lysis was seen, whereas under identical conditions in the parent strain, stationary-phase lysis started after 2 to 3 h (Fig. 9C).

Incorporation of choline.

Since some of the preceding observations suggested incorporation of choline into LTA and TA, JY2190 was grown in choline-containing CDM (5 mg/liter), and LTA and TA were isolated as described above. Choline was released from both polymers by HF. Analysis revealed a molar ratio of choline to phosphorus of 0.45, which compares with 0.54 in Rx1/AL−. These data let us calculate that in JY2190, on average 82% of the repeats are substituted with one phosphocholine residue, the rest being unsubstituted, whereas in Rx1/AL−, on average 83% of the repeats are substituted with one phosphocholine residue and the rest are substituted with two.

Transformation of the mutant in the absence of choline.

Using our standard transformation medium (THY–0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA]–0.01% CaCl2 [43]), we did not observe transformation of the mutant. However, when JY2190 was grown in CDM containing BSA and CaCl2, transformation was observed whether or not choline was present in the medium (Table 3). JY2190 transformed at a lower efficiency than Rx1, and peak competence occurred at a lower cell density under both conditions (Table 3). In addition, the mutant grew more slowly and achieved a lower maximum cell density when cultured in the absence of choline in the CDM transformation medium than when cultured in the presence of choline in this medium. In the latter case, growth appeared identical to that of the parent Rx1 (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Transformation of JY2190a

| Strain | Choline | Transformation frequency (%)b | Cell density |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rx1 | + | 0.020 | 5.5 × 107 |

| JY2190 | + | 0.001 | 1.5 × 107 |

| JY2190 | − | 0.004 | 6.5 × 106 |

Bacteria were grown in CDM containing 0.2% BSA, 0.01% CaCl2, and, where indicated, 5 μg of choline per ml. Transformants were selected on BAP containing erythromycin (0.3 μg/ml). The maximum transformation frequency obtained and the cell density at which it occurred are shown. Identical results were obtained in two independent experiments.

Determined as (erythromycin-resistant CFU/total CFU) × 100.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe the isolation of a pneumococcal mutant which has acquired the capability to grow in the absence of choline and analogs. Isolation and analysis of LTA and TA from the mutant grown in CDM revealed both polymers to be free of phosphocholine and other phosphorylated amino alcohols. The proved absence of phosphoethanolamine precludes mutationally induced, endogenous synthesis of EA, which would render growth independent of nutritional choline. The choline-free cell walls of the mutant were totally resistant against the action of pneumococcal autolysin, which has a specific requirement for phosphocholine residues on cell wall-linked TA (22). In vivo, the inactivity of the autolytic enzyme led to impaired cell separation at the end of cell division and rendered the cells resistant to stationary-phase and penicillin-induced lysis. When JY2190 was grown in the presence of choline, LTA and TA were substituted with phosphocholine to about 80% of the phosphocholine substitution in Rx1/AL−. The walls of these cells were susceptible to hydrolysis with autolysin, the cells separated normally, penicillin-induced lysis was restored, and PspA was retained at the cell surface. In contrast to penicillin-induced cell lysis, stationary-phase lysis was not restored. Since both kinds of lysis are effected by autolysin, the reason for this distinction may reside in the triggering of lysis rather than in the lysis step itself. Other deviations from the wild type were poor reactivity of cell lysates with monoclonal antibody specific for phosphocholine and the release of larger amounts of material that was reactive with antibody to the TA (C-polysaccharide). For unknown reasons, the material released from JY2190 and Rx1 was only weakly reactive with antibody specific for phosphocholine.

The results of compositional analysis along with the novel fingerprint identification let us propose that the repeats of LTA and TA from the mutant and from strain Rx1/AL− are identical to each other and to the structures previously reported for the LTA and TA from S. pneumoniae R6 (3, 12). There was also no change in the linkage of the repeats by phosphodiester bonds between O-5 of the ribitol and O-6 of the adjacent glucosyl moieties. Moreover, the LTAs from the three strains possess the same glycolipid anchor and have similar lengths of between five and seven repeats. The cell wall of the mutant appeared also not to be affected: as indicated by the contents of the constituents, the cellular amounts of peptidoglycan and TA were similar in the mutant and Rx1/AL−. The phosphate content of the cell walls of the mutant was half that of strain Rx1/AL−, consistent with the absence of choline phosphate from TA. Also similar in both strains were the lengths of TA chains, which varied between six and eight repeats. Since the choline-free LTA and TA of the mutant were in all structural details identical to their choline-containing counterparts in Rx1 and R6, it is unlikely that these structures are altered when nutritional choline is incorporated.

The ability of S. pneumoniae to undergo genetic transformation was lost when choline was replaced in the cell wall by EA (38). That transformability cannot be dependent on choline itself is indicated by the present observation that the mutant retained this capability even when grown in the absence of choline. Compared to Rx1, transformation was less frequent and occurred at an earlier stage of growth, but these differences also existed during growth in the presence of choline.

The metabolic background responsible for the change from a strict requirement for nutritional choline or its analogs to the ability to dispense with such compounds is not yet understood. A hint may come from in vitro experiments that provided evidence that the synthesis of peptidoglycan, which is the basis of cell growth, was inhibited by choline deprivation (9). On the basis of this observation, a metabolic interdependence of TA and peptidoglycan metabolism was suggested: the two polymers may be synthesized in linkage to polyprenol phosphate, and only completed TA, substituted with phosphocholine or phosphoethanolamine, is transferred to peptidoglycan. Accordingly, polyprenol phosphate-linked TA lacking these substituents would not be transferred but would trap polyprenol phosphate and render it unavailable for peptidoglycan synthesis (9). If this hypothesis proves correct, the nutritional requirement of choline may reside in a recognition site for phosphoamino alcohols on TA, by which the activity of the TA-transferase is regulated. Accordingly, the mutation may cause the activity of the transferase to become independent of this regulation, making a transfer of nonsubstituted TA to cell walls possible. Further genetic and biochemical characterizations of the mutant are under way and are expected to provide insights into the mechanisms involved in synthesis of the TAs and peptidoglycan of S. pneumoniae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work in the laboratory of W.F. was supported by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung grant 01KI 9401/2.

We thank all colleagues who generously provided bacterial strains, enzymes, and antibodies. The skilled and reliable technical assistance provided by Barbara Orlicz-Welcz and Christian Emilius in the structural studies and by Rosie McKinney and the UAB Electron Microscopy Center is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Assmann G, Schriewer H. Choline. In: Bergmeyer H U, Bergmeyer J, Grassl M, editors. Methods of enzymatic analysis. VIII. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1985. pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badger E. The structural specificity of choline for the growth of type III pneumococcus. J Biol Chem. 1944;153:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr T, Fischer W, Peter Katalinic J, Egge H. The structure of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid. Improved preparation, chemical and mass spectrometric studies. Eur J Biochem. 1992;207:1063–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry A M, Lock R A, Hansman D, Paton J C. Contribution of autolysin to virulence of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2324–2330. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.8.2324-2330.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briese T, Hakenbeck R. Interaction of the pneumococcal amidase with lipoteichoic acid and choline. Eur J Biochem. 1985;146:417–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Briles E B, Tomasz A. Membrane lipoteichoic acid is not a precursor to wall teichoic acid in pneumococci. J Bacteriol. 1975;132:335–337. doi: 10.1128/jb.122.1.335-337.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brundish D E, Baddiley J. Pneumococcal C-substance, a ribitol teichoic acid containing choline phosphate. Biochem J. 1968;110:573–582. doi: 10.1042/bj1100573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon J S, Lipkin D. Spectrophotometric determination of vicinal glycols. Anal Chem. 1954;26:1092–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer H, Tomasz A. Peptidoglycan cross-linking and teichoic acid attachment in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:46–54. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.46-54.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer W. Pneumococcal lipoteichoic and teichoic acid. Microb Drug Resist. 1997;3:209–324. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer W, Koch H U, Haas R. Improved preparation of lipoteichoic acids. Eur J Biochem. 1983;133:523–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer W, Behr T, Hartmann R, Peter Katalínic J, Egge H. Teichoic acid and lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus pneumoniae possess identical chain structures. A reinvestigation of teichoic acid (C polysaccharide) Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:851–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer W, Markwitz S, Labischinski H. Small-angle X-ray scattering analysis of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid phase structure. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:913–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer, W., R. Hartmann, and G. Pohlentz. Unpublished data.

- 15.Garcia E, Garcia J L, Ronda C, Garcia P, López R. Cloning and expression of the pneumococcal autolysin gene in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;201:225–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00425663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia E, Garcia J L, Garcia P, Arrarás A, Sanchez-Puelles J M, López R. Molecular evolution of lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:914–918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia J L, Garcia E, Arrarás A, Garcia P, Ronda C, López R. Cloning, purification, and biochemical characterization of the pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 lysine. J Virol. 1987;61:2573–2580. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.8.2573-2580.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidicelli S, Tomasz A. Attachment of pneumococcal autolysin to wall teichoic acids, an essential step in enzymatic degradation. J Bacteriol. 1984;158:1188–1190. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.3.1188-1190.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hannappel E, Kaibacher H, Voelter W. Thymosin β4Xen. A new thymosin β4-like peptide in oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;260:546–551. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heumann D, Barras C, Severin A, Glauser M P, Tomasz A. Gram-positive cell walls stimulate synthesis of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2715–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2715-2721.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Höltje J-V, Tomasz A. Lipoteichoic acid: a specific inhibitor of autolysin activity in Pneumococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1690–1694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Höltje J-V, Tomasz A. Specific recognition of choline residues in the cell wall of teichoic acid by the N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase of pneumococci. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:6072–6076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jennings H J, Lugowski C, Young N M. Structure of the complex polysaccharide C-substance from Streptococcus pneumoniae type I. Biochemistry. 1980;19:4713–4719. doi: 10.1021/bi00561a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunst A, Draeger B, Ziegenhorn J. d-Glucose. In: Bergmeyer H U, Bergmeyer J, Grassl M, editors. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd ed. VI. Metabolites 1: carbohydrates. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1984. pp. 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu T-Y, Gotschlich E C. Muramic acid phosphate as a component of the muropeptide of gram-positive bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:471–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDaniel L S, Scott G, Kearney J F, Briles D E. Monoclonal antibodies against protease sensitive pneumococcal antigens can protect mice from fatal infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 1984;160:386–397. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nägele U, Wahlefeld A W, Ziegenhorn J. Triglycerides. In: Bergmeyer H U, Bergmeyer J, Grassl M, editors. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd ed. VIII. Metabolites 3: lipids, amino acids and related compounds. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1985. pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ough L D. Chromatographic determination of saccharides in starch hydrolysates. Methods Carbohydr Chem. 1964;4:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poxton I R, Tarelli E, Baddiley J. The structure of C-polysaccharide from the walls of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Biochem J. 1978;175:1033–1042. doi: 10.1042/bj1751033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rane L, Subbarow Y. Nutritional requirements of the pneumococcus. I. Growth factors for types I, II, V, VII, and VIII. J Bacteriol. 1940;40:695–704. doi: 10.1128/jb.40.5.695-704.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez-Puelles J M, Ronda C, Garcia J L, Garcia P, Lopez R, Garcia E. Searching for autolysin functions. Characterization for a pneumococcal mutant deleted in the lytA gene. Eur J Biochem. 1986;158:289–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Puelles J M, Sanz J M, Garcia J L, Garcia E. Cloning and expression of gene fragments encoding the choline-binding domain of pneumococcal murein hydrolases. Gene. 1990;89:69–75. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanz J M, Lopez R, Garcia J L. Structural requirements of choline derivatives for ‘conversion’ of pneumococcal amidase. A new single-step procedure for purification of this autolysin. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:308–313. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaller K H, Triebig G. Formate determination with formate dehydrogenase. In: Bergmeyer H U, Bergmeyer J, Grassl M, editors. Methods of enzymatic analysis. 3rd ed. VI. Metabolites 1: carbohydrates. Weinheim, Germany: Verlag Chemie; 1984. pp. 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schnitger H, Papenberg K, Ganse E, Czok R, Bücher T, Adam H. Chromatographie phosphathaltiger Metabolite eines menschlichen Leberpunktates. Biochem Z. 1959;332:167–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoemaker N B, Guild W R. Destruction of low efficiency markers is a slow process occurring at a heteroduplex stage of transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1974;138:283–290. doi: 10.1007/BF00268516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strominger J L, Park J T, Thompson R E. Composition of the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus: its relation to the mechanism of the action of penicillin. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:3263–3268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomasz A. Biological consequences of the replacement of choline by ethanolamine in the cell wall of pneumococcus: chain formation, loss of transformability, and loss of autolysin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:86–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tomasz A, Westphal M. Abnormal autolytic enzyme in a pneumococcus with altered teichoic acid composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2627–2630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.11.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomasz A, Westphal M, Briles E B, Fletcher B. On the physiological functions of teichoic acids. J Supramol Struct. 1975;3:1–16. doi: 10.1002/jss.400030102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomasz A, Moreillon P, Pozzi G. Insertional inactivation of the major autolysin gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5931–5934. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5931-5934.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van de Rijn I, Kessler R E. Growth characteristics in group A streptococci in a new chemically defined medium. Infect Immun. 1980;27:444–448. doi: 10.1128/iai.27.2.444-448.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yother J, McDaniel L S, Briles D E. Transformation of encapsulated Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1463–1465. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1463-1465.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yother J, Handsome G L, Briles D E. Truncated forms of PspA that are secreted from Streptococcus pneumoniae and their use in functional studies and cloning of the pspA gene. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:610–618. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.610-618.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yother J, White J M. Novel surface attachment mechanism of the Streptococcus pneumoniae protein PspA. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2976–2985. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.10.2976-2985.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]