Throughout the past decade, smoking has remained the single most important modifiable cause of poor pregnancy outcome in the United States. It accounts for 20% of deliveries of infants with low birth weights, 8% of preterm births, and 5% of all perinatal deaths.1 New studies have found that maternal smoking during pregnancy contributes to sudden infant death syndrome and may cause important changes in fetal brain and nervous system development.2,3,4,5,6,7 New economic estimates indicate that the direct medical costs of a complicated birth for a smoker are 66% higher than for nonsmokers, reflecting the greater severity of complications and the more intensive care required.8 Although quitting smoking early in pregnancy is most beneficial, important health benefits accrue from quitting at any time during the pregnancy.1

Moreover, the health hazards and health care burden to women and their family members caused by smoking do not begin or end with pregnancy. Before pregnancy, smoking increases the risk of serious medical complications for women using oral contraceptives and can impair fertility.1 After pregnancy, in addition to adversely affecting women's health, smoking exposes infants and young children to environmental tobacco smoke. This exposure is linked to sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory tract illnesses, middle-ear infections, and decreased lung function.3,4,9 Currently, 27% of US children aged 6 years and younger are exposed to tobacco smoke at home,10 the annual direct medical costs of parental smoking are estimated at $4.6 billion, and loss-of-life costs are estimated at $8.2 billion.11

Recent national survey data indicate that the goal of reducing smoking among pregnant women from 25% in 1985 to 10% by the 2000 was not met.12 Some reduction was achieved, but about 20% of US women currently smoke during pregnancy, based on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's 1994, 1995, and 1996 national surveys (table).13 Rates are highest among unmarried women and among women with less than a high school education, with the smoking rate for low-income Medicaid enrollees estimated at approximately 35%. This translates to 1 in 5 US births or pregnancies, or 800,000 births per year.14 However, these survey data are likely to underestimate the true prevalence of smoking during pregnancy.15,16,17 Growing public awareness of the adverse effects of smoking on pregnancy has led an increasing number of pregnant smokers to conceal or underreport their smoking behavior.17,18

Table 1.

Percentage reporting past-month cigarette use in the US population of women aged 15 to 44 years, by pregnancy status and demographic characteristics*

| Demographic characteristics | Past-month cigarette use, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant | Not pregnant | |

| Total | 20.6 | 31.9 |

| Age, yr | ||

| 15 to 24 | 27.2 | 31.1 |

| 26 to 44 | 15.9 | 32.3 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 23.3 | 35.1 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 20.9 | 29.0 |

| Hispanic | 11.6 | 21.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 15.7 | 27.2 |

| Not married | 32.5 | 36.8 |

| Adult education | ||

| Less than high school | 44.0 | 49.1 |

| High school graduate | 21.8 | 37.8 |

| Some college | 13.3 | 30.6 |

| College graduate | 7.4 | 17.2 |

From Office of Applied Studies, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1996.13 Data are annual averages based on 1994, 1995, and 1996 samples combined.

The goal adopted for the year 2010 is to reduce cigarette smoking among pregnant women to a prevalence of no more than 2%.12 This is an especially ambitious goal given that rates of smoking among teenaged girls have risen substantially in the first half of the last decade.15 While they have begun to decline, rates of smoking among college students and peers their same age continue to rise as the previous group ages. The 1999 Monitoring the Future Survey found that more than a third of 12th-grade girls (17-18 years of age) report smoking in the past 30 days.19 Without vigorous, widespread, and innovative efforts during the next decade, we are unlikely to achieve this new goal. Hence, as we enter a new decade and a new century, reducing national smoking rates in pregnancy remains a national public health priority.

PREGNANCY AS A SPECIAL WINDOW OF OPPORTUNITY

Pregnancy and the period preceding and following it provide a unique teachable moment to help women stop smoking. Women are highly motivated to stop smoking during this time, when they are concerned not only about their own health but that of their infants. They also are likely to experience higher levels of social and family support for quitting. Accordingly, about 25% of women smokers quit smoking either as they prepare to become pregnant or as soon as they learn that they are.20,21 Like-wise, pregnant women have greater contact with the health care system. Many women who do not otherwise seek or receive primary care or preventive services can be reached during family planning and prenatal care visits, with follow-up later in hospitals, pediatric offices, health clinics, day care programs, and during home nursing visits.22

Similarly, providers and health care systems have especially compelling reasons to intervene, given the dramatic and immediate health benefits of quitting for the pregnant woman and her baby and the significant cost savings associated with averting pregnancy complications and deliveries of low-birth-weight infants.8 Health care professionals can take advantage of women's unique quitting motivation by reinforcing knowledge that quitting smoking will reduce health risks to the fetus and reviewing the important postpartum benefits for both mother and child.3,4,9

Moreover, as outlined in the article by Mullen and colleagues,23 the past 15 years of intervention research has established that brief (5-15 minutes) medical quitting advice and counseling, combined with pregnancy-tailored behavioral self-help quitting guides provided in the course of routine prenatal care, produces quit rates that are significantly higher than those achieved with usual care (that is, 14%-16% vs 5%-6%), including among the most underserved low-income women.17,20,21,24 Given the substantial savings associated with averting the delivery of infants with low birth weights, these “best practice” interventions have also proved highly cost-effective. It is estimated that for every $1 invested in these interventions, about $6 is saved, with the result that the current best practice for brief cessation counseling in pregnancy is likely, for smokers, to be more cost-effective than all the rest of prenatal care.21,25,26,27,28

A 2-PART CHALLENGE

To achieve the ambitious national goal set for 2010, two challenges must be addressed. First, vigorous efforts are needed to make the current best-practice intervention the standard for prenatal care with all pregnant smokers. Second, new research must be done to develop more powerful interventions and to address the problems of high rates of smoking nondisclosure among pregnant smokers and of postpartum relapse among pregnant smokers who do succeed in quitting.

Unfortunately, most prenatal care providers fail to implement even the most basic best-practice interventions. National survey data compiled for Healthy People 2000 indicate that only 49% of obstetricians and gynecologists routinely advise cessation and provide assistance and follow-up for all their tobacco-using patients (pregnant and nonpregnant), and only 28% go on to discuss cessation strategies.10 These statistics fall way short of the 2000 and 2010 best-practice intervention goal of 75% of all providers.10,12 Only 45% of managed care plans surveyed in 1997-1998 reported offering a smoking-cessation strategy that targeted pregnant women specifically.29 Of these 147 plans that did offer a pregnancy specific strategy, only 40% followed the clinical guidelines of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR; now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) for smoking cessation in designing their program.30 Furthermore, in 1999, only 24 states (2 more than in 1998) reported coverage for any nicotine addiction treatment services under Medicaid, which provides health insurance coverage for 60% to 70% of all pregnant smokers, and only 10 states covered the nonmedication counseling interventions appropriate for most pregnant smokers.31,32 These data underscore the critical need to understand and address provider, systems, and policy barriers to routine intervention in prenatal care.

Second, the quit rates of even the most effective best-practice interventions for pregnant smokers seldom reach or exceed 20%, with lower rates among the most addicted smokers.20,21,24 More than two thirds of women who quit smoking during pregnancy return to smoking cigarettes within 6 months following delivery.33 Some of the factors contributing to these statistics—such as the multiple stresses and lifestyle changes (diet, exercise, alcohol intake) associated with pregnancy and breast feeding and normal postpartum depression—can make it harder to quit during pregnancy and to continue to abstain afterward. In addition, pharmacotherapies that have proved effective in increasing the quit rates associated with behavioral and counseling interventions, including nicotine replacement therapies and bupropion hydrochloride,34,35,36 are not recommended for general use with pregnant smokers, given the uncertain balance of risks and benefits to the fetus and the pregnancy.34,36,37 This raises the need for creative research to develop more powerful behavioral and counseling treatments to motivate and assist pregnant smokers to quit and help sustain their abstinence after delivery.

To address this 2-part challenge, staff at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and in the Smoke-Free Families National Program Office have launched a number of related strategies to, one, promote the wider integration of current best-practice interventions into routine prenatal care; and, two, support innovative studies with promise to improve the efficacy of smoking-related behavioral interventions.38,39 These strategies are outlined below.

DISSEMINATING CURRENT BEST-PRACTICE INTERVENTIONS

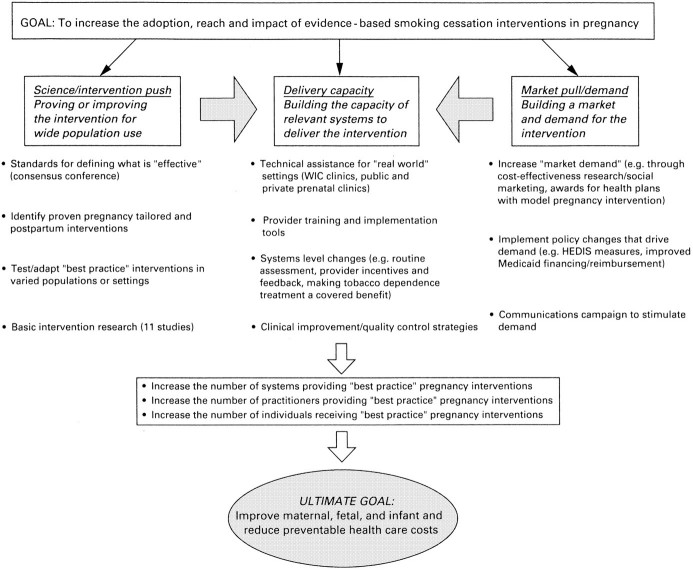

Our efforts to promote the wider integration of the current best-practice intervention into routine prenatal care have included activities to strengthen and publicize the science base for these treatment strategies, build demand for them, and expand the capacity of providers and health care systems to deliver them. They are described below with reference to a proposed generic “market-oriented” product development model illustrated in the figure.34,40 According to this model, 3 related types of activity are required:

Strengthening science, or intervention, “push” by proving or improving an intervention for wide population use;

Boosting market demand or “pull” for proven interventions; and

Building the capacity of relevant systems to deliver or implement them.

Increasing science or intervention “push” generally involves developing standards for defining what is effective and either or both developing and promulgating clinical practice guidelines, and conducting further research to test or adapt effective interventions in new settings or populations or to improve on intervention efficacy. Viewed in this framework, the 1996 release of the AHCPR smoking cessation clinical practice guideline represented a major “science push.”34 To capitalize on this push, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in collaboration with the AHCPR, awarded “guideline dissemination grants” to the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American Medical Women's Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics. These grants supported their efforts to publicize the guideline through their professional journals and meetings and to develop and disseminate tailored versions of the guideline for women, including pregnant women and mothers and parents of young children. It also supported the American Cancer Society's efforts to disseminate a “packaged” state-of-the-art intervention and organized a consensus conference with other major funders (for example, the American Cancer Society; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]; the National Cancer Society; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute) to identify the essential elements of the current best-practice intervention for smoking cessation in pregnancy, based on a comprehensive literature review and a review of early results of trials in progress. A subsequent conference, organized in collaboration with the National Institute of Child Health and Development, explored the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy to revise current guidelines for nicotine replacement and other approved products for pregnant and lactating women.37 The fruits of these efforts have been shared with the expert panel compiling the AHCPR's updated guidelines and are reflected in the revised 2000 guideline.36 To improve on current best practice and pave the way to the next generation of more powerful interventions, the Smoke-Free Families National Program funded a series of innovative studies, which are described in the next section of this article.

We assumed that having a clearer picture of the costs of smoking in pregnancy and of economic benefits of effective treatment could motivate more health plans and health care policymakers to incorporate the evidence-based treatments into the routine care they provide for pregnant smokers. Therefore, to help build demand or market pull, Melvin and colleagues41 estimated the full range of maternal and infant health care costs associated with maternal smoking during pregnancy, and economic analyses were conducted to lay the groundwork for estimating the cost benefits of Smoke-Free Families best practice and innovative treatment approaches. Our other efforts to increase demand have included ongoing qualitative social marketing research to find the most compelling ways to portray the benefits of current best-practice interventions to health plans, insurers, providers, pregnant smokers, and their families; efforts to inform the health care policymakers of the health and cost benefits covering evidence-based tobacco dependence treatment for all pregnant smokers enrolled in Medicaid; efforts to broaden the current Health Plan Employer Data Information Set measure of managed care provider intervention to quit smoking42; and in conjunction with the American Association of Health Plans and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's Addressing Tobacco in Managed Care national program, the creation of an annual award to recognize health plans that have successfully implemented tobacco cessation strategies before, during, and after pregnancy. These efforts may lay the groundwork for a national communications campaign aimed at patients, providers, insurers, and health plans, potentially in collaboration with the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Neither push nor pull can work alone to drive the adoption of best-practice interventions without efforts to build the health care system's capacity to deliver them. Capacity-building efforts began with support for an effort to catalogue the existing self-help materials that met best-practice standards to make it easier for providers and health plans to obtain them,43 and included (in collaboration with AHCPR) support for training programs offered by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American Cancer Society, and the American Medical Women's Association to train practicing prenatal care providers to offer these interventions routinely. In addition, the American Association of Health Plans and Addressing Tobacco in Managed Care's national technical assistance office provide tools and technical assistance to health plans seeking help to implement best-practice interventions for their pregnant and postpartum smokers. Also, the Addressing Tobacco in Managed Care research program is funding a variety of grants to evaluate the effects of varied systems changes—such as making tobacco use a vital sign, offering incentives or feedback to providers, and including tobacco dependence treatment as a covered benefit—on the adoption of evidence-based smoking-cessation strategies, including those for pregnant smokers.44,45,46,47 Future capacity-building efforts will include a partnership with the CDC and Health Resources and Services Administration to support region-by-region quality improvement efforts to expand the capabilities of a range of prenatal health care systems to deliver best-practice interventions routinely.

Our hope is that these combined efforts will help to create a policy and practice environment favorable to the widespread adoption of current best-practice interventions for pregnant smokers. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Smoke-Free Families National Program will continue to seek to work with other funders, public and private, and a variety of stakeholders, including professional societies, to change the standard of care for pregnant smokers.

DEVELOPING MORE POWERFUL INTERVENTIONS

To help pave the way for the next generation of more effective interventions for pregnant smokers, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and its Smoke-Free Families National Program have supported a range of innovative studies evaluating novel smoking-cessation approaches that had not been previously tested (“Smoke-Free Families: Innovations to Stop Smoking During and Beyond Pregnancy,” call for proposals, 1994). Convinced that treatment “breakthroughs” would be most likely to result from funding for interventions that reflected some “thinking outside the box” or employed promising new technologies (for example, interactive video, computer-tailored self-help materials), 11 controlled 2-year pilot studies were funded. These studies involved pregnant smokers from a variety of populations who were seen in varied public and private treatment settings, from those in the Women, Infants, and Children Supplemental Food Program and public health prenatal clinics, to private offices, group practices, and managed health care plans. The grantees included investigators from several different backgrounds and disciplines—medicine, nursing, behavioral psychology, epidemiology, public health, health education, and neuropharmacology—with several projects led by interdisciplinary research teams.

Because prospecting for breakthrough treatments necessarily entails some risk, we did not expect that all the interventions would prove to be significant improvements on the current best practice. However, our hope was to identify a few breakthrough interventions that would be competitive for larger scale investigations supported by the National Institutes of Health and to learn more about barriers to making brief interventions a part of routine prenatal and postpartum care, no matter what the intervention result. The Tobacco Control supplement (2000, supplement 3) presents the fruits of these studies. Several promising interventions were identified, and 3 investigators have been successful in gaining National Institutes of Health support for follow-on research. A great deal was learned about the practical challenges to be addressed in conducting controlled research in clinical settings and in expanding existing prenatal care to include systematic tobacco intervention.

From the findings presented in the supplement, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Smoke-Free Families National Program office have gone on to craft a second-generation effort—to explore further promising interventions suggested by the first and to address several knowledge gaps that are holding back the field. As a result, $11.5 million has been committed to fund controlled and pilot studies to identify effective motivational interventions using patient incentives and/or biochemical feedback of smoking health harms, combined with core best-practice interventions; identify additional innovative treatments for achieving smoking cessation during and immediately after pregnancy; and support exploratory research to learn more about the determinants of smoking nondisclosure, spontaneous quitting before and early in pregnancy, and postpartum maintenance and relapse (“Smoke-Free Families: Innovations to Stop Smoking During and Beyond Pregnancy, Phase II,” call for proposals, 1999). In addition, $5 million has been committed to fund the creation of a national dissemination office to work in concert with the national program office and with other funders and stakeholder groups to promote the widespread adoption of current and future best-practice interventions for pregnant smokers. Our commitment is to continue to work with other organizations and agencies to build on the lessons learned from the work presented in the Tobacco Control supplement and to disseminate widely promising new practices as they develop. Our aim is to help assure that we collectively meet the nation's important 2010 health goals.

Figure 1.

Model of the types of effort required to improve integration of evidence-based behavioral intervention into routine medical care to achieve smoking cessation in pregnancy

Figure 2.

Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome and other health problems in newborns

[Hart-Davis/SPL]

Figure 3.

New and powerful interventions are needed to help women stop smoking during pregnancy and after delivery

[Alexandre/SPL]

Acknowledgments

Pennington Whiteside and Richard Windsor provided editorial assistance, and Dawn Young and Robyn Shumer provided clerical support.

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.US Dept of Health and Human Services. The Health Benefits of Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General, 1990. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Office on Smoking and Health; 1990. DHHS publication (CDC) 90-8416.

- 2.Anderson HR, Cook DG. Passive smoking and sudden infant death syndrome: review of the epidemiological evidence. Thorax 1997;52: 1003-1009 [erratum published in Thorax 1999;54:365-366]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Lew RA. Effect of maternal cigarette smoking on pregnancy complication and sudden infant death syndrome. J Fam Pract 1995;40: 385-394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiFranza JR, Lew RA. Morbidity and mortality in children associated with the use of tobacco products by other people. Pediatrics 1996;97: 560-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haglund B, Cnattingius S. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Public Health 1990;80: 29-32 [erratum published in Am J Public Health 1992;82:1489]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambers DS, Clark KE. The maternal and fetal physiologic effects of nicotine. Semin Perinatol 1996;20: 115-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slotkin TA. The impact of fetal nicotine exposure on nervous system development and its role in sudden infant death syndrome. In: Benowitz NL, ed. Nicotine Safety and Toxicity. New York: Oxford Press; 1998: 89-97.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Medical-care expenditures attributable to cigarette smoking during pregnancy—United States, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1997;46: 1048-1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wisborg K, Henriksen TB, Obel C, Skajaa E, Ostergaard JR. Smoking during pregnancy and hospitalization of the child. Pediatrics 1999;104: e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2000 Review. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1999 1998. DHHS publication (PHS) 99-1256.

- 11.Aligne CA, Stoddard JJ. Tobacco and children: an economic evaluation of the medical effects of parental smoking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151: 648-653. [erratum published in Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151:988] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010 Objectives: Draft for Public Comment. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1998. US DHHS Healthy People 2000 citation.

- 13.Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Preliminary Results From the 1996 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA 1997;90:table 32B. DHHS publication (SMA) 97-3149. [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Dept of Health and Human Services. Live births by race of mother [table 4]. Monthly Vital Stat Rep 1997;46(suppl 2): 12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebrahim SH, Floyd RL, Merritt RK II, Decoufle P, Holtzman D. Trends in pregnancy-related smoking rates in the United States, 1987-1996. JAMA 2000;283: 361-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendrick JS, Zahniser SC, Miller N, et al. Integrating smoking cessation into routine public prenatal care: the Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy project. Am J Public Health 1995;85: 217-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Windsor RA, Woodby LL, Miller TM, Hardin JM, Crawford JA, Di Clemente CC. Effectiveness of Agency for Health Care Policy and Research clinical practice guideline and patient education methods for pregnant smokers in Medicaid maternity care. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182(pt 1): 68-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen PD, Carbonari JP, Tabak ER, Glenday MC. Improving disclosure of smoking by pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165: 409-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston L. Cigarette Smoking Among American Teens Continues Gradual Decline. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan News and Information Service; December 17, 1999.

- 20.Ershoff DH, Mullen PD, Quinn VP. A randomized trial of a serialized self-help smoking cessation program for pregnant women in an HMO. Am J Public Health 1989;79: 182-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Perkins LL, et al. Health education for pregnant smokers: its behavioral impact and cost benefit. Am J Public Health 1993;83: 201-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abrams D, Orleans C, Niaura R, et al. Integrating individual and public health perspectives for treatment of tobacco dependence under managed care: a combined stepped-care and matching model. Ann Behav Med 1996;18: 290-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melvin CL, Dolan-Mullen P, Windsor PA, Whiteside HP Jr, Goldenberg RL, Recommended cessation counselling for pregnancy women who smoke: a review of the evidence. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 3): III80-III84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Windsor RA, Cutter G, Morris J, et al. The effectiveness of smoking cessation methods for smokers in public health maternity clinics: a randomized trial. Am J Public Health 1985;75: 1389-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li CQ, Windsor RA, Lowe JB, Goldenberg RL. Evaluation of the impact of dissemination of smoking cessation methods on the low birthweight rate and on health care costs: achieving year 2000 objectives for the nation. Am J Prev Med 1992;8: 171-177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marks JS, Koplan JP, Hogue CJ, Dalmat ME. A cost-benefit/cost-effectiveness analysis of smoking cessation for pregnant women. Am J Prev Med 1990;6: 282-289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shipp M, Croughan-Minihane MS, Petitti DB, Washington AE. Estimation of the break-even point for smoking cessation programs in pregnancy. Am J Public Health 1992;82: 383-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Windsor RA, Warner KE, Cutter GR. A cost-effectiveness analysis of self-help smoking cessation methods for pregnant women. Public Health Rep 1988;103: 83-87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPhillips-Tangum C. Results from the first annual survey on addressing tobacco in managed care. Tob Control 1998;7(suppl): S11-S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barker DC, Robinson LA, Rosenthal AC. A survey of managed care strategies for pregnant smokers. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 3): III46-III50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker DC, Orleans CT, Schauffler HH. Tobacco treatment services should be covered under Medicaid [letter]. Tob Control 1998;7: 92-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schauffler HH, Barker DC, Orleans CT. 1999 Medicaid coverage for tobacco dependence treatments. Health Aff (Millwood); 2000;20: 298-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fingerhut LA, Kleinman JC, Kendrick JS. Smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. Am J Public Health 1990;80: 541-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Smoking Cessation: Clinical Practice Guideline No. 18. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; April 1996. AHCPR publication 96-0692.

- 35.Jorenby DE, Leischow S, Nides MA, et al. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med 1999;340: 685-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US Public Health Service. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guidelines. US Dept of Health and Human Services; June 2000.

- 37.Benowitz NL, Dempsey DA, Goldenberg RL, et al. The use of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 3): III91-III94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orleans CT. Challenges and opportunities for tobacco control: the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation agenda. Tob Control 1998;7(suppl): S8-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orleans CT, Gruman J, Anderson N. Roadmaps for the Next Frontier: Getting Evidence-Based Behavioral Medicine into Practice. Presented at a meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, San Diego, CA, March 4, 1999.

- 40.Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. Putting Evidence Into Practice. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; 1999.

- 41.Melvin CL, Adams EK, Miller V. Costs of smoking during pregnancy: development of the maternal and child health smoking attributable mortality, morbidity, and economic costs (MCHSAMMEC) software. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 3): III12-III15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.HEDIS 3.0: Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set. Washington, DC: National Committee for Quality Assurance; July 1996.

- 43.Winders SE, Raczynski JM, Westfall E, et al. Smoking Cessation and Environmental Tobacco Smoke Reduction: Materials Targeting Pregnant Women and Families. Birmingham: Division of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, and Dept of Health Behavior, School of Public Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham; 1997.

- 44.Bentz CJ. Implementing tobacco tracking codes in an individual practice association or a network model health maintenance organisation. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 1): I42-I45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson CL, Chute P, Dacey S, McAfee TA. Designing tobacco control systems and cessation benefits in managed care: skill building workshop. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 1): I25-I29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Isham GJ. A proactive health plan: taking action on tobacco control. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 1): I15-I16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solberg LI. Incentivising, facilitating, and implementing an office tobacco cessation system. Tob Control 2000;9(suppl 1): I37-I41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]