Abstract

Objective To examine the contribution of employment status, welfare benefits, alcohol use, and other individual and contextual factors to physical aggression during marital conflict. Methods Logistic regression models were used to analyze panel data collected in the National Survey of Families and Households in 1987 and 1992. A total of 4,780 married or cohabiting persons reinterviewed in 1992 were included in the analysis. Domestic violence was defined as reporting that both partners were physically violent during arguments. Results Unemployed respondents are not at greater risk of family violence than employed respondents, after alcohol misuse, income, education, age, and other factors are controlled for; however, employed persons receiving welfare benefits are at significantly higher risk. Alcohol misuse, which remains a predictor of violence even after other factors are controlled for, increases the risk of family violence, and satisfaction with social support from family and friends is associated with its decrease. Conclusions Alcohol misuse has an important effect on domestic violence, and the potential impact of welfare reform on domestic violence needs to be monitored.

Family violence has been recognized as a public health problem for almost a decade,1 and the health care cost associated with the treatment of family violence injuries in the United States has been estimated as high as $857 million annually.2 In analyzing 1985 National Violence Survey data, Straus and Gelles found an annual incidence of marital aggression of about 16%.3 In 1992, 12% of all homicides were the result of intrafamilial violence.4 Estimates are that as many as 2 to 4 million women a year are physically battered by their intimate partners.5 Women are as likely as men to resort to physical aggression during marital conflicts, but women are more likely to report injury from such interchanges.6

Family violence has been associated with gender and power issues7,8,9; structural and sociodemographic characteristics such as age, socioeconomic status, unemployment, cohabiting status, and partnership stability10,11,12,13; alcohol and drug misuse14,15; and depression.16,17 The research on family violence has produced results that are difficult to integrate conceptually or empirically. Most of this research has been on small selected samples and cross-sections.

The role of alcohol in violence is especially controversial.14,18,19 Studies have found that alcohol use may aggravate marital difficulties, leading to separation or divorce,17 and alcohol problems may have an indirect effect on earnings and marriage.20,21 One longitudinal study, however, found that alcohol consumption was significantly related to physical aggression 6 months immediately before and after marriage, but the effects washed out at 18 months.22 Others have suggested that structural factors such as unemployment may disrupt community and social relationships, leading to greater risk behavior such as alcohol consumption.13 Unemployment, however, has been inconsistently related to both alcohol intake13,23 and violent incidents.24 Job loss has been found to be related to an increase of negative behaviors between partners,24 but again, the relation between job loss and violence is not clear-cut. Although small increases in layoffs are associated with more violent incidents, large increases are associated with a reduced incidence.25

Employment in itself does not necessarily protect couples from marital violence. Stressful work experiences have also been associated with wife abuse.26 In addition, it has been suggested that an increase of female employment and transitions toward different forms of relationships may generate tensions that increase the likelihood of marital violence.27 This is particularly relevant given our fast-changing economy and increasing employment demands on young parents,28,29 including those receiving welfare benefits.

There is evidence that welfare reform accounted for 44% of the employment rate gain from 1992 to 199630,31 and that the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-193) has forced more women with young children to work. In the current policy debate, not only is there little concern for the effect of welfare reform on women's health,32 but little thought has been given to a potential for increased domestic violence.

Social scientists increasingly note the importance of taking context into account when explaining outcomes and the necessity of looking at the way in which family, work, and community factors interrelate to explain attitudes and behaviors.33,34,35,36 Research on violence should also consider the effects of social and economic environmental factors.37,38

The goal of this study was to contribute to our understanding of the complex and important issue of family violence. Using panel data from the 1987 and 1992 National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), we attempted to disentangle the effects of employment, partnership instability, and alcohol use on the risk of domestic violence.

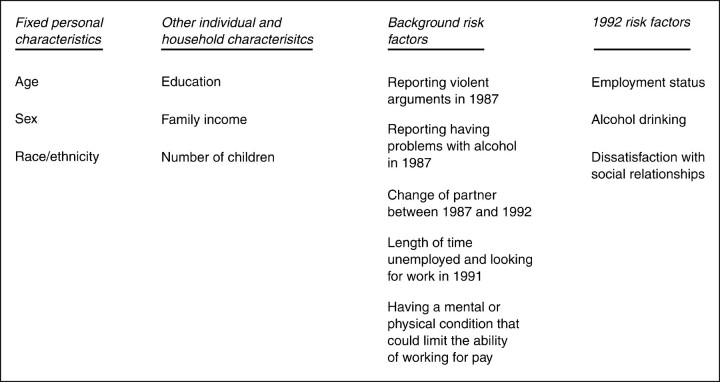

The figure summarizes our explanatory model. We took advantage of longitudinal data, and controlling for individual and household characteristics and prior problems with alcohol misuse, violent arguments, and joblessness (1987 and 1991 variables), we ascertained the influence of current alcohol misuse and employment status on current violence (1992 variable). Our explanatory model draws from a sociostructural approach, in that violent arguments are seen as arising from changing and increasing demands placed on the family,26,38 and from a social learning approach that considers the influence of variables such as occupational status on the onset of violence.26 We broadened the employment status variable to include working and receiving welfare.

METHODS

Data

The 1987 NSFH survey consisted of interviews with 13,017 respondents, including an oversample of minorities and households containing single-parent families, stepfamilies, recently married couples, and cohabiting couples. The 1992 survey includes a reinterview of 10,008 surviving members of the original sample, which represents an attrition rate of 23%. We analyzed possible differences between respondents to the 1992 survey and those who were unavailable for follow-up after the 1987 interview. No significant differences were noted in attrition rates by sex, age, ethnic group, and marital status between those who were reinterviewed and those unavailable for follow-up. We limited our study to respondents who were older than 16 years in 1987 and who were not retired in 1992. A total of 4,770 married or cohabiting persons were included in our analyses.

Measures

In this study, we focused on violent arguments in which both partners participated. About 60% of respondents who engaged in violent arguments in 1992 (151/247) reported that both partners used physical violence. Of 247 respondents who reported having violent arguments, only 25 reported being the only perpetrator of violence, and 71 said that only the spouse or partner used violence. We considered these 2 groups to be too small to include in our analysis and excluded them. We explored possible reporting differences between the 3 variants of family violence—that is, spouse or partner violent, respondent violent, and both mutually violent. In general, those who reported that only the partner used physical violence were, on average, older (mean age, 35.4 years vs 33.4 years) and more educated (mean of 13.6 years vs 12.5 years) than those who also reported being active participants in violent arguments.

As noted in a previous analysis of the NSFH, women were as likely as men to commit violent acts, but women were more likely than men to report being injured.39 We focused on predictors of violent interchanges and not on their possible consequences.

Our dependent variable, family violence, was measured by the question: In the past year, did both respondent and partner become physically violent during an argument? We investigated possible differences between respondents and nonrespondents to this question in gender, alcohol drinking patterns, race or ethnicity, and total number of children in the household. The number of nonrespondents was small (n=171), and no significant differences were observed between groups.

We constructed an employment situation variable from several variables that asked about respondents' employment and sources of income in 1992. Respondents were divided into 4 categories: full-time employed, parttime employed, working while receiving welfare benefits, and unemployed. Given the few episodes of violence reported by retired people (only 2 of 327 retired respondents reported violence), this group was not included in our analysis. Of all 1,055 unemployed respondents, only 76 were looking for work, and of those, only 6 reported violent arguments, which did not allow us to look at them separately. In addition, 208 unemployed respondents were receiving some type of social or welfare benefits. Preliminary analysis showed that they did not differ statistically from other nonworking people, and we kept them together to increase the statistical power of our model.

We used the total number of drinks that the respondent had in the past 30 days as our measure of alcohol drinking in 1992. Covariates we controlled for were the respondent's sex, age, race or ethnicity, partnership stability, years of education, total household income, number of children in the household, satisfaction with friends and family, and having a mental or physical condition that could limit the ability to work for pay. Partnership stability was measured as 3 different types of partnership: respondents who were in stable relationships (that is, married or living together in 1992 to the same person as in 1987), those who have a different partner from the 1 they had in 1987, and new couples (that is, were not married or living together in 1987). Besides considering partnership stability, we explored whether other partner characteristics such as having had problems with alcohol or drugs could have an effect on predicting family violence. However, few respondents indicated that their partners or other family members had had problems with drugs or alcohol in 1987, and we were not able to include this variable in our analysis.

Other background factors included in our model were number of weeks unemployed and looking for work in 1991, reporting engaging in violent arguments in 1987, and having alcohol problems in 1987.

Statistical analysis

We conducted logistic regression analyses to examine the relations of interest using commercial software (SAS/STAT, version 6; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). In all our analyses, we weighted the survey responses to account for the oversampling of special populations in the survey, including African American, single-parent families, families with stepchildren, cohabiting couples, and recently married persons. The weights were prepared by the NSFH researchers.40 We used Box-Cox transformation of the income and alcohol intake variables, a frequently used procedure that smoothes out the effect of outlier values and approximates the variables to a normal distribution. The transformations were sufficient to produce reasonable residual plots (see tables on the wjm web site, www.ewjm.com, for details on the transformations used). We examined the correlations among all variables, performed diagnostic tests for collinearity, and found no problems.

We did not replace any missing values of the dependent variable. For the categorical independent variables, we added an additional group of “no response or not applicable,” where necessary, to include all respondents in our analysis. For the continuous independent variables, we replaced missing values by imputing them with the predicted value estimated for the age, sex, ethnic, marital status, and employment situation group of the respondent.

First, we conducted logistic regression in our full model described in the figure. To have sufficient cell size to examine interaction effects between employment situation and social support, alcohol use, and number of children, we then dropped some of the variables that were not significant in our first analysis and created a shorter model. Our reduced model controlled for age, sex, income, education, and prior violence (1987) while analyzing the effects of current employment status, alcohol drinking, satisfaction with relationships, and number of children in the household. We then ran 3 separate models with interactions for satisfaction with relationships, alcohol misuse, and number of children.

RESULTS

A description of our sample is given in table 1 (see the table on our web site, www.ewjm.com). Of 4,780 respondents, 151 reported engaging in arguments in which both partners were physically violent toward each other.

The average household income and years of education are lower among those who report violent arguments than among those who do not report them. Respondents who engaged in violent arguments had more children and reported drinking more alcohol and more weeks of unemployment in 1991 than respondents who did not report violence. The average age of respondents engaging in violent arguments was 33 years (SD 6.7), and the average age of those not resorting to violence was 40 years (SD 10.0).

People employed full time were less likely and those working while receiving welfare benefits were more likely to report violence than other employment status groups. Working part-time and being unemployed did not increase the risk of violence. African American respondents reported more violent arguments than white respondents or those categorized as others.

Because of sample size considerations, we were not able to analyze men and women separately. (See table 1 on the wjm web site, www.ewjm.com, for a description of the sample by gender group.)

The results of our first logistic regression analyses using the full model described in the figure are shown in table 2 (see the wjm web site). Significant predictors for violent arguments included number of children in the household, alcohol drinking in 1992, and previous (1987) history of engaging in violent arguments. The risk of violence was greater for people who were working while receiving welfare than for the referent (full-time employed) group.

Two factors that significantly reduced the likelihood of engaging in violent arguments were age and satisfaction with relationships with family (other than spouse) and friends. Higher income and education were also associated with less likelihood of reporting violence, but the confidence intervals are relatively wide.

Men and women did not differ significantly in reporting having arguments in which both partners were physically violent. Other factors that are not statistically significant in predicting violence include race or ethnicity, partnership stability, having a physical or mental limitation that could restrict the ability to work for pay, the number of weeks of unemployment while looking for work in 1991, and previous (1987) history of having alcohol problems.

The results of our reduced model where we dropped variables that did not attain significance in the full model are shown in table 3 (see the wjm web site), and 3 separate models are shown that include reduced model variables and interaction effects for employment status and satisfaction with relationships or alcohol misuse or number of children. In our reduced model, people working while receiving welfare were almost 4 times more likely to report violence than other working respondents. The number of alcohol drinks and of children in the family were again significant risk factors for violent arguments, and satisfaction with social relationships significantly protects against violence.

We calculated interactions of employment status with the other 3 factors significantly associated with violence and of theoretical interest to dissatisfaction with relationships, number of alcohol drinks, and number of children in the family in separate, parallel models. Relative to full-time workers, a higher number of children significantly increased the risk of violence for unemployed respondents. Relative to full-time workers, more alcohol drinks slightly increased the risk of violence for unemployed workers. The number of children and of alcohol drinks did not significantly increase the risk of violence for those working while receiving welfare relative to full-time workers. Satisfaction with relationships did not significantly interact with employment status to predict violence. We did not include a model with all main and interaction effects because of cell size considerations. Thus, we could not simultaneously compare the modifying effects of alcohol drinks, satisfaction with relationships, and number of children on the relationship between employment status and violence.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we focused on arguments in which both partners engaged in physical violence, which represented about 60% of incidents of family violence in the NSFH. People who are only recipients of violence by their partners may have different characteristics from those who react violently and should be studied separately. In addition, our sample included respondents who were in a stable relationship between 1987 and 1992 and those who were in a new or different relationship in 1992. Respondents who were not in a relationship in 1992 could not be included in the analysis. Generalizations to the entire US population should be made cautiously.

The greatest strength of this study is that it is based on a national probability sample, thereby reducing sample selection bias, and it includes a rich set of important variables to permit examination of possible confounders. Furthermore, in contrast with popular perception, race or ethnicity is not a significant factor in predicting violent arguments when other factors are accounted for. Partnership instability has not been controlled for in previous studies of alcohol and family violence, but in our study, partnership instability was not a risk factor for violence, after other factors were controlled for.

As previously reported in the literature, alcohol use is positively associated with violent arguments in the same year. Alcohol use 5 years earlier seemed not to affect current violence. Research has not previously clarified the modifying effect of alcohol misuse on the relation between unemployment and violence. We found that alcohol interacted with unemployment to predict violence; alcohol use, moreover, did not increase the risk of violence among other employed groups in relation to full-time employed persons. Note that we used a measure of alcohol intake widely used in the alcohol research literature (that is, number of drinks in the past 30 days).41 Many of our other variables of interest reported events in the past 6 or 12 months, which may possibly limit the usefulness of the alcohol use variable. We were constrained in our choice of this variable because the NSFH does not provide information on whether the alcohol drinking pattern of respondents differed during the rest of the year.

This study has certain limitations. Our exclusion criteria, and the factors we controlled for in our model, should have eliminated most of the differences among the various groups of people included in our model, but uncontrolled variables determining both resources and outcomes may have remained. People who have antisocial personality characteristics are also likely to drink in large amounts,42,43,44 making causal interpretations difficult because of possible confounding of characteristics of people most likely to be violent with the circumstances under which they drink and become violent. Neither personality characteristics nor circumstances can explain alcohol-related violence without consideration of the purposes served by drinking and the properties of alcohol in relation to violence.45 Personality characteristics were not included as variables in our study, but we controlled for a previous history of both violence and alcohol problems. Those who reported violent arguments in 1987 were almost 6 times more likely to report violence in 1992.

Underreporting is an additional limitation of most studies of family violence because it is a sensitive issue about which people may be hesitant to speak openly. The possible reasons for underreporting in the NSFH data have been previously discussed.39 The NSFH placed the violence questions in the middle of a lengthy interview and kept the questions general rather than specific. In addition, the questions referred to violence only in the context of disagreements, although violent abuse could occur without being prompted by a disagreement, and sexual violence was not included in the definition. When we analyzed the small number of missing responses to the violence questions, we did not find evidence of differences between respondents and nonrespondents in age, sex, or marital status.

Sample size considerations did not allow us to run models separately for men and women, taking into account who was the perpetrator of the violence. In future research, it would be useful to study men and women separately to better understand the possible relation between women's employment patterns, the age of children in the household, and other determinants that could influence the permanence of women in violent relationships. In future studies, it would also be useful to include additional information on partners' characteristics. Larger sample sizes, new methods of diminishing underreporting, and different methodologic approaches may be necessary to build on this line of research.

Perhaps the most important findings of this study are the increased risk of violence if working and receiving welfare and the inhibiting effect on violence of satisfaction with social relationships. Our findings are particularly relevant in view of recent welfare reform strategies. Our results indicate that, relative to the employed, people working while receiving welfare could be at greater risk for violence.

One plausible explanation for the increased risk for respondents receiving welfare while working is that the additional stress associated with working in low-skills jobs when coping with poverty and child care issues puts people at a higher risk of family violence. Recent research shows that working couples with small children tend to work more hours than others, and they report the lowest quality of life among working couples (P Moen et al, annual meeting of the American Association of Science, Anaheim, CA, January 1999). However, we found that having more children slightly increased the risk of violence only for unemployed persons relative to full-time workers. This suggests that job conditions (for example, low-skill or less secure), personality characteristics, stigma related to receiving welfare, or some other unmeasured characteristic may explain this intriguing finding.

We should continue to take a comprehensive approach to problems of domestic violence. We have identified a group who is particularly at risk for family violence, which makes it critical to monitor the effect of welfare reform on family violence.

Summary points

Employed persons receiving welfare benefits are at significantly higher risk of domestic violence

Unemployed respondents are not at greater risk of family violence than employed persons. However, alcohol misuse interacts with unemployment to predict violence

In contrast with popular perception, race or ethnicity is not a significant factor in predicting violent arguments when other factors are accounted for

Two factors that significantly reduce the likelihood of engaging in violent arguments are age and satisfaction with relationships with friends and family (other than the spouse)

Figure 1.

Explanatory model

Figure 2.

Victims of domestic violence urge California legislators to pass an expanded domestic violence bill

AP/Max Whittaker

Acknowledgments

The data were generously provided by the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The survey was designed and carried out at the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin under the direction of Larry Bumpass and James Sweet. Field work was done by the Institute for Survey Research at Temple University, Philadelphia. A previous version of this article was presented at the International Conference on Research for Social Work Practice, North Miami, FL, January 1998.

Funding: Cornell Agricultural Experiment Station provided a Hatch Grant for this research effort. Funding for the National Survey of Families and Households was by grant HD21009 from the Center for Population Research of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Competing interests: None declared.

This article was published in J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:172-178

References

- 1.Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 1991.

- 2.Campbell JC, Lewandowski LA. Mental and physical health effects of intimate partner violence on women and children. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997;20: 353-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straus MA, Gelles RJ. How violent are American families? estimates from the National Family Violence Resurvey and other studies. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, eds. Physical Violence in American Families: Risk Factors and Adaptations to Violence in 8,145 Families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990: 95-112.

- 4.Uniform Crime Reports (UCR): Crime in the US. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation; 1994.

- 5.Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Steinmetz SK. Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family. New York, NY: Anchor Books; 1981.

- 6.Brush L. Violent acts and injurious outcomes in married couples: new data from the National Survey of Families and Household. National Survey of Families and Households Working Paper 6. Madison: University of Wisconsin; 1989.

- 7.Dobash RE, Dobash RP. Violence Against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy. New York, NY: Free Press; 1979.

- 8.Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: 2 forms of violence against women. J Marriage Fam 1995;57: 283-294. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yllo K. Political and methodological debates in wife abuse research. In: Yllo K, Bogard M, eds. Feminist Perspectives on Wife Abuse. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1988: 28-50.

- 10.Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Intimate Violence: the Causes and Consequences of Abuse in the American Family. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 1988.

- 11.Gelles RJ, Loseke DR. Current Controversies on Family Violence. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

- 12.Anderson KL. Gender, status, and domestic violence: an integration of feminist and family violence approaches. J Marriage Fam 1997;59: 655-669. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin RL, Shah CP, Svoboda TJ. The impact of unemployment on health: a review of the evidence. J Public Health Policy 1997;18: 275-300. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roizen J. Issues in the epidemiology of alcohol and violence. Alcohol Interpersonal Violence 1993;1: 3-35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pernanen K. Alcohol in Human Violence. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1991.

- 16.Yegidis BL. Family violence: contemporary research findings and practice issues. Community Ment Health J 1992;28: 519-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gortner ET, Gollan JK, Jacobson NS. Psychological aspects of perpetrators of domestic violence and their relationships with the victims. Psychiatr Clin North Am 1997;20: 337-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WV, Weinstein SP. How far have we come? a critical review of the research on men who batter. Recent Dev Alcohol 1997;13: 337-356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pernanen K. Alcohol-related violence: conceptual models and methodological issues. In: Martin SE, ed. Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1993: 37-69.

- 20.Kenkel DS, Ribar DC. Alcohol consumption and young adults' socioeconomic status. Brooking Pap Eco Ac1994;1: 119-175. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ninth Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1997.

- 22.Heyman RE, O'Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives. J Fam Psychol 1995;9: 44-57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Arcy C. Unemployment and health: data and implications. Can J Public Health 1986;77: 124-131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vinokur AD, Price RH, Caplan RD. Hard times and hurtful partners: how financial strain affects depression and relationship satisfaction of unemployed persons and their spouses. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;71: 166-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catalano R, Novaco R, McConnell. A model of the net effect of job loss on violence. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997;72: 1440-1447. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barling J, Rosenbaum A. Work stressors and wife abuse. J Applied Psychol 1986;71: 346-348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kornblit AL. Domestic violence—an emerging health issue. Soc Sci Med 1994;39: 1181-1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishel L, Bernstein J, Schmitt J. The State of Working America 1996-97. Economic Policy Institute Series. New York, NY: Armonk: M E Sharpe; 1997.

- 29.Rodriguez E. Social benefits and the life-cycle: understanding the predictors of part-time versus full-time employment. Res Sociol Work 2000;8: 165-185. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer B, Rosenbaum D. Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single Mothers. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Joint Center for Poverty Research; 1998.

- 31.Bishop JH. Is Welfare Reform Succeeding? Working paper 98-15. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Center for Advanced Human Resources Studies; 1998.

- 32.Wise PH, Elman D. Topics for our times: welfare reform and women's health. Am J Public Health 1998;88: 1017-1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aldwin CM. Stress, Coping, and Development: an Integrated Prospective. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995.

- 34.McKenry PC, Julian TW, Gavazzi SM. Toward a biopsychosocial model of domestic violence. J Marriage Fam 1995;57: 307-320. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menaghan EG. Work experiences and family interaction processes: the long reach of the job? Annu Rev Sociol 1991;17: 419-444. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weed DL. Beyond black box epidemiology. Am J Public Health 1998;88: 12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levine FJ, Rosich KJ. Social Causes of Violence: Crafting a Science Agenda. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1996.

- 38.Wallace D, Wallace R. Scales of geography, time, and population: the study of violence as a public health problem. Am J Public Health 1998;88: 1853-1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brush LD. Violent acts and injurious outcomes in married couples: methodological issues in the National Survey of Families and Households. Gender Society 1990;4: 56-67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sweet JA. Bumpass LL, Call VRA. National Survey of Families and Households, 1987-1994. Madison: University of Wisconsin Center for Demography and Ecology; 1999.

- 41.Caetano R. The epidemiology of alcohol-related problems in the US: concepts, patterns and opportunities for research. Drugs Society 1997;11: 43-71. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gelles RJ, Cornell CP. International Perspectives on Family Violence. Lexington, KY: Lexington Books; 1983.

- 43.Leonard KE, Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Day NL, Ryan CM. Patterns of alcohol use and physically aggressive behavior in men. J Stud Alcohol 1985;46: 279-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKenna T, Pickens R. Alcoholic children of alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol 1981;42: 1021-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCord J. Considerations of causes in alcohol-related violence. In: Martin SE, ed. Alcohol and Interpersonal Violence: Fostering Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1993: 71-79.