Abstract

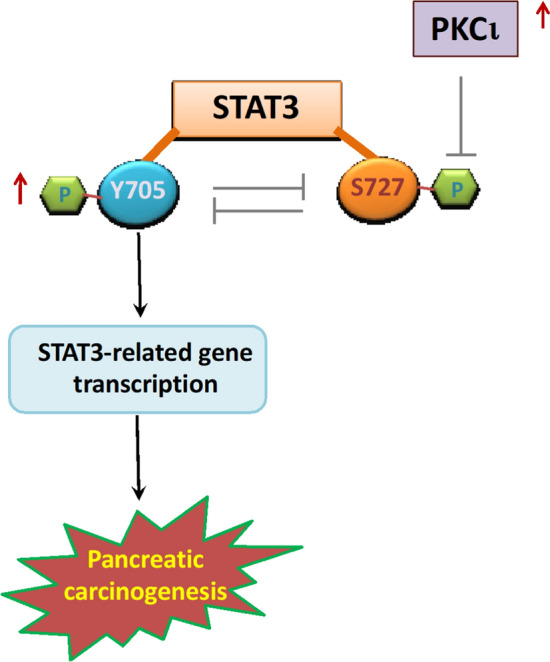

An increasing number of studies have documented atypical protein kinase C isoform ι (PKCι) as an oncoprotein playing multifaceted roles in pancreatic carcinogenesis, including sustaining the transformed growth, prohibiting apoptosis, strengthening invasiveness, facilitating autophagy, as well as promoting the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment of pancreatic tumors. In this study, we present novel evidence that PKCι overexpression increases STAT3 phosphorylation at the Y705 residue while decreasing STAT3 phosphorylation at the S727 residue in pancreatic cancer cells. We further demonstrate that STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705 and S727 residues is mutually antagonistic, and that STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation is positively related to the transcriptional activity of STAT3 in pancreatic cancer cells. Furthermore, we discover that PKCι inhibition attenuates STAT3 transcriptional activity via Y705 dephosphorylation, which appears to be resulted from enhanced phosphorylation of S727 in pancreatic cancer cells. Finally, we investigate and prove that by modulating the STAT3 activity, the PKCι inhibitor can synergistically enhance the antitumor effects of pharmacological STAT3 inhibitors or reverse the anti-apoptotic side effects incited by the MEK inhibitor, thereby posing as a prospective sensitizer in the treatment of pancreatic cancer cells.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12079-023-00780-9.

Keywords: PKCι, STAT3, Differential phosphorylation, Sensitizer

Introduction

Protein kinase C isoform ι (PKCι) belongs to the atypical kinase C subfamily, which is insensitive to co-factors such as calcium or diacylglycerol, but relies on protein–protein interaction for activation (Griner et al. 2007; Moscat et al. 2009; Ono et al. 1998). Through regulating a variety of key signaling pathways that are involved in cell survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and metastasis, PKCι has been documented by multiple studies to be able to drive malignant transformation in diverse tumors, including non-small-cell lung carcinoma, colon cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, stomach cancer, glioblastoma, cholangiocarcinoma, liver and pancreatic cancer (Fields et al. 2007; Scotti et al. 2010). Recent research by us and others has affirmed the roles of PKCι in promoting proliferation, restricting apoptosis, maintaining autophagy, and encouraging immunosuppression, therefore contributing to the initiation and progression of pancreatic cancer, as well as the development of drug resistance (Inman et al. 2022; Kawano et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2018, 2020; Yang et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021). This establishes PKCι as a promising therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer treatment.

Pancreatic cancer is the most malignant tumor with the lowest survival rate around the world, owing primarily to a lack of early-stage symptoms and targeted treatment modalities. The characteristic desmoplastic stroma of the pancreatic tumor not only constitutes a hypoxia milieu favoring oncogenic adaptation, but also shields the transfusion and uptake of chemotherapeutic compounds (Singh et al. 2021; Ying et al. 2016). As a result, novel drugs that can both block the malignant transformation and inhibit the oncogenic effects of the tumor microenvironment (TME) hold the promise of improving outcomes in pancreatic cancer treatment.

In a previous study, we identified that PKCι promotes carcinogenesis and immunosuppressive TME in pancreatic tumors (Wang et al. 2018, 2020; Yang et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021). Additionally, we found that PKCι affects the activity of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) by inducing STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells (Zhang et al. 2021). STAT3 is a transcription factor (TF) regulating the expression of a plethora of target genes involved in various cancer-associated cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, stemness, metastasis, anti-apoptosis, angiogenesis, inflammation, and so on (Philips et al. 2022). It is required for the oncogenesis of numerous epithelial malignancies (Chen et al. 2008; Corcoran et al. 2011; Khan et al. 2018; Takemoto et al. 2009). Here, we continue our investigation into how PKCι regulates STAT3 activity in PDAC. We discovered that decreased phosphorylation of STAT3 at S727, another phosphorylation site that has been reported to modulate the transcriptional activity of STAT3, invariably occurs in conjunction with enhanced phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 mediated by PKCι. Further analysis revealed that phosphorylation at the Y705 and S727 residuals in STAT3 is always reversely correlated, and that PKCι -mediated phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 is probably through a process involving STAT3 S727 dephosphorylation in PDAC cells. Moreover, we found that a few chemical inhibitors, including STAT3 inhibitors (Stattic, AZD1480) and a MEK inhibitor (Trametinib), also modulate the phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 in a S727-dependent manner in PDAC cells. Furthermore, when used in combination, PKCι inhibition greatly potentiates the anti-tumor activity of STAT3 inhibitor and MEK inhibitor against PDAC cells, and it reduces the proliferation and invasion elicited by human pancreatic stellate cells (HPSC) in TME, partially via inhibiting IL-6-STAT3 signaling. In sum, these results point to PKCι inhibitor as a prominent sensitizer that can both synergize the anti-tumor effects of other therapeutic drugs and ameliorate the oncogenic effects of TME in PDAC treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines MiaPaCa-2 and PANC-1 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (VA, USA). The human pancreatic stellate cell (HPSC) was purchased from BeNa Culture Collection (Henan, China). The pancreatic cancer cell lines were maintained in DMEM or RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (MHBio, China). The HPSC was cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All cells used in this study were tested for absence of mycoplasma contamination. The authenticity of the cells was determined by short tandem repeat analysis.

Reagents and constructs

Sodium aurothiomalate (ATM) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Stattic, AZD1480 and Trametinib were all from APExBIO (TX, USA). Antibodies against PKCι (BD Biosciences, USA), PDL1, pSTAT3(S727) (Abcam, USA), pSTAT3(Y705), Bcl-xL, Cyclin D1 (Cell signaling Technology, USA), total STAT3, Ki67, Twist, Vimentin, GAPDH (Zen Bioscience, China), were used. Lipofectamine 2000 from Invitrogen (MD, USA) was utilized for transfections.

The pLentiLox 3.7 plasmid containing small interference RNA sequences targeting PKCι, and the plasmid overexpressing PKCι (pCMV-PKCI) were constructed before (Wang et al. 2018). The small interfering RNA targeting PKCι was purchased from Hunter Biotech (Zhejiang, China). The cDNA of STAT3 was subcloned into pCMV-HA to establish pCMV-STAT3, which was then used as template to construct plasmids overexpressing various mutants of STAT3, including pCMV-STAT3-Y705D, STAT3-Y705F, STAT3-Y640F, STAT3-S727E and STAT3-S727A. The sequence of pdl1 promoter was subcloned into a dual-luciferase expression vector pGL-dual (Yang et al. 2021) to generate pGL-pdl1promo.

Immunoblot

Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide (SDS) gel electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membranes, blocked with 5% non-fat milk, and then probed with primary and secondary antibodies before they were visualized with chemiluminescence. All experiments were performed at least three times to confirm the results, and a representative result for each experiment was shown and analyzed. ImageJ was used to quantify signal intensities of targeted proteins, which were then normalized to their internal reference protein (GAPDH or total STAT3) and graphed as a fold change compared to control samples.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

The total RNAs were prepared using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). The cDNAs were reversely transcribed and analyzed by CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, USA) to determine the expressions of target genes. All qRT-PCR experiments were repeated to confirm the consistency of the results.

Luciferase assay

Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured between 24 and 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (KeyGen BioTECH, Jiangsu, China) and a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Apoptosis detection assay

Apoptotic cells in various samples were analyzed by Annexin V-PE apoptosis detection kit (Sungene Biotech, China) as instructed by the manufacturers and measured with a FACS Celesta flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

Cell viability assay

Trypsin-dissociated cells were plated in 6-well plates. The number of the cells was counted in three wells during the subsequent 6 to 8 days and plotted against time to generate cell growth curve.

Wound-healing assay

The PDAC cells were cultured on plates for 48 h to reach 90% confluence. A straight scratch was then created by the tip of a sterile pipette on the cell monolayer. After removing the cell debris with PBS washing, the cells were incubated under various conditions for 24 h and the wound width was detected by an inverted microscope (Mshot M112, Guangdong, China), analyzed with ImageJ to evaluate the migration of PDAC cells.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine statistical significance of the results. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

PKCι causes differential phosphorylation of STAT3 at the Y705 and S727 residuals in pancreatic cancer cells

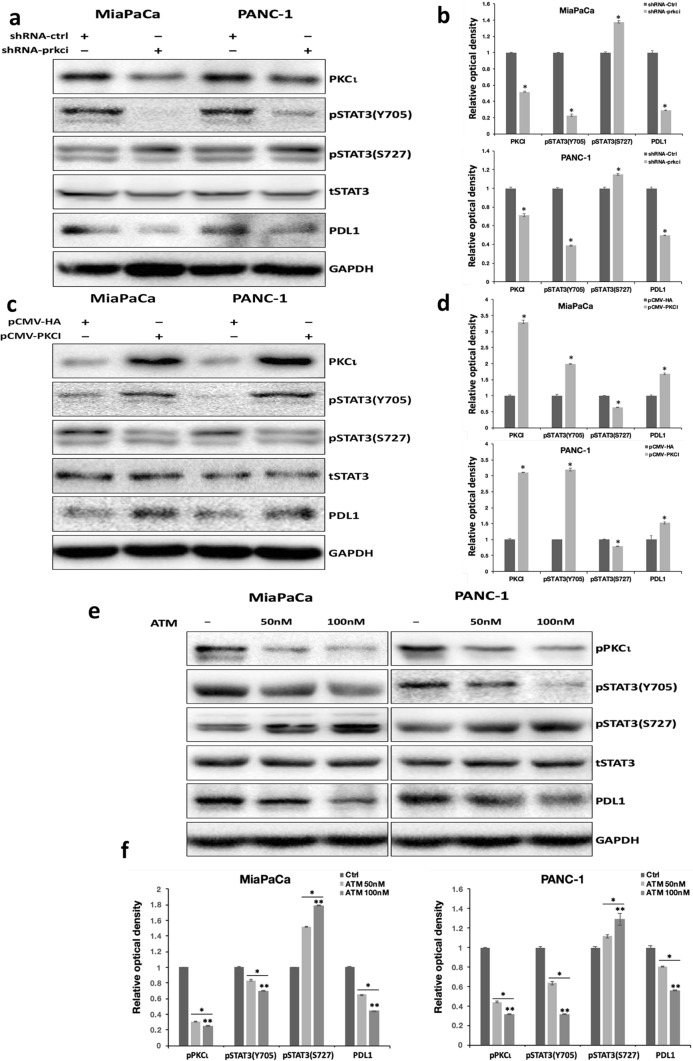

In a prior study, we discovered that PKCι can modulate the transcriptional activity of STAT3 by inducing the residual phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 (pY705 STAT3) in various PDAC cells. In an effort to better understand how PKCι regulates STAT3 phosphorylation in PDAC, we investigated the effect of PKCι on another phosphorylation site in STAT3, the S727 residual. Our results revealed that, contrary to its effect on Y705 phosphorylation, inhibition of PKCι expression by prkci-targeted short-hairpin RNA (shRNA-prkci) led to elevated phosphorylation of S727 in STAT3 (pS727 STAT3) in PDAC cell lines MiaPaCa and PANC-1(Fig. 1a, b), whereas ectopic expression of PKCι blocked pS727 STAT3 while increasing pY705 STAT3 (Fig. 1c, d). Next, we treated MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells with various concentrations of ATM, a chemical inhibitor of PKCι. In agreement with our previous findings, we uncovered that ATM suppressed the pY705 STAT3 in PDAC cells in a dose-dependent manner. By contrast, the pS727 STAT3 was gradually enhanced with increasing concentrations of ATM (Fig. 1e, f).

Fig. 1.

PKCι induces differential phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues in PDAC. a Immunoblot analyses of the protein levels of PKCι, phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues, total STAT3, PDL1 and GAPDH in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells transduced with lentiviral control or prkci-targeting shRNA. b The relative optical density of the protein bands depicted in a. The densitometry of protein bands on Western blots was quantified by image J. The optical intensity of PKCι and PDL1 bands was normalized by GAPDH, whereas that of phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 or S727 bands was normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of the control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control). c Immunoblot detection of PKCι, phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues, total STAT3, PDL1 and GAPDH in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells transfected with pCMV-HA (void vector) or pCMV-PKCI. d The relative optical density of the protein bands presented in c. The optical intensity of phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 or S727 bands was normalized by total STAT3, and that of the others was normalized by GAPDH. The relative optical density of the control protein bands was set as 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control). e Immunoblot analyses of phosphorylated PKCι, phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues, total STAT3, PDL1 and GAPDH in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells treated with vehicle, 50 nM or 100 nM ATM. f The relative optical density of the protein bands presented in e. The optical intensity of phosphorylated STAT3 at Y705 or S727 bands was normalized by total STAT3, and that of the others was normalized by GAPDH. The relative optical density of control protein bands was set as 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control, ** p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with 50 nM ATM)

Since we had previously pinpointed pdl1 as a STAT3 target gene in PDAC (Zhang et al. 2021), here we used pdl1 as a reporter gene in our experiments to assess STAT3 transcriptional activity. Our data displayed that blocking STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation via PKCι shRNA or ATM suppressed PDL1 expression, whereas increasing pY705 STAT3 by PKCι overexpression enhanced PDL1 levels in PDAC cells (Fig. 1a–f). These findings suggest that STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation is positively related to STAT3 transcriptional activity in pancreatic cancer cells.

To rule out any off-target effects of shRNA-prkci, we employed another PKCι -targeting small interfering RNA (siRNA-prkci2) to validated the differential STAT3 phosphorylation mediated by PKCι inhibition in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, we identified that Cyclin D1 and Bcl-xL, two bona fide STAT3 target genes, as well as PDL1, were downregulated in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 transfected with siRNA-prkci2 (Supplementary Fig. 1). By contrast, Cyclin D1 and Bcl-xL levels were elevated in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 overexpressing PKCι (Supplementary Fig. 2). In line with these immunoblotting findings, our quantitative PCR (qPCR) analyses revealed that inhibiting PKCι by shRNA-prkci or siRNA-prkci2 both reduced the mRNA expression of multiple STAT3 target genes, including pdl1, ccnd1, bcl2l1, and c-myc, whereas PKCι overexpression increased the expression of these genes in PDAC (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). Moreover, PKCι inhibitor ATM was also shown to constrain the mRNA levels of STAT3 target genes in PDAC cells (Supplementary Fig. 3d). These data demonstrate that PKCι can regulate the expression of a variety of STAT3 target genes.

Add together, our results show that PKCι enhances the pY705 STAT3 while reducing pS727 STAT3 to modulate the transcriptional activity of STAT3 in PDAC cells.

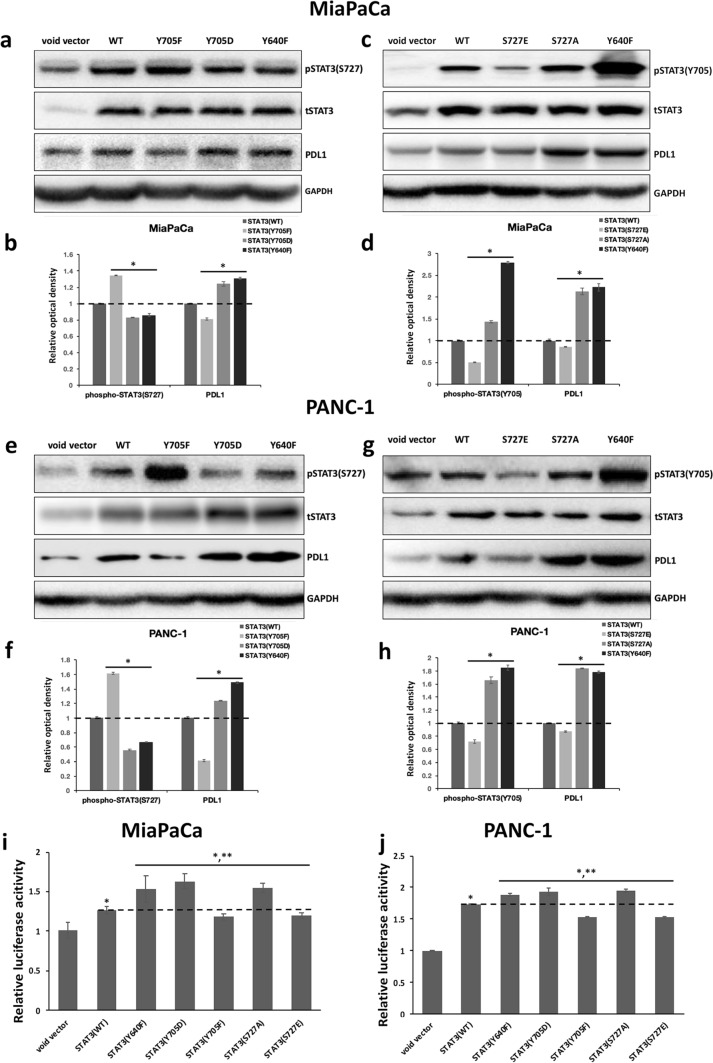

STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705 or S727 is reversely correlated and influences the transcriptional activity of STAT3 differently in pancreatic cancer cells

We then examined the potential interconnection between STAT3 Y705 and S727 phosphorylation in pancreatic cancer cells. The plasmids overexpressing wild-type STAT3, phospho-mimetic mutants of Y705 (STAT3-Y705D) and S727 (STAT3-S727E), or phospho-inactivating mutants of Y705 (STAT3-Y705F) and S727 (STAT3-S727A) were constructed. We also generated STAT3-Y640F, a hypermorphic mutant known to cause constitutive Y705 phosphorylation in STAT3. Our investigation showed that in comparison to wild-type STAT3, overexpression of STAT3-Y705D and STAT3-Y640F repressed, while STAT3-Y705F augmented pS727 STAT3 levels in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells (Fig. 2a, b, e, f). Reversely, overexpression of STAT3-S727E weakened, whereas STAT3-S727A strengthened STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705. The increased levels of pY705 STAT3 were also confirmed in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells overexpressing STAT3-Y640F (Fig. 2c, d, g, h. We didn't display the pY705 blots of Y705 mutants or the pS727 blots of S727 mutants here since we discovered that mutations at Y705 or S727 altered STAT3’s immunoreactivity with antibodies against pY705 or pY727 STAT3).

Fig. 2.

The antagonistic effect between STAT3 Y705 and S727 phosphorylation in PDAC cells. a and e Immunoblot analyses of the levels of phosphorylated STAT3 at S727, total STAT3, PDL1, and GAPDH in (a) MiaPaCa and (e) PANC-1 cells transfected with void vector, or plasmid overexpressing wild-type STAT3 (WT), STAT3-Y705F, -Y705D, or -Y640F. b and f The relative optical intensity of protein bands shown in a and e. The optical density of pS727 STAT3 bands was normalized by total STAT3 and that of PDL1 was normalized by GAPDH. The relative optical density of proteins in control cells overexpressing wild-type STAT3 was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control). c and g Immunoblot detection of the levels of pY705 STAT3, total STAT3, PDL1, and GAPDH in c MiaPaCa and g PANC-1 cells transfected with void vector, or plasmid overexpressing STAT3-WT, -S727E, -S727A, or -Y640F. d and h The relative optical intensity of protein bands shown in c and g. The optical intensity of pY705 STAT3 was normalized by total STAT3 and that of PDL1 was normalized by GAPDH. The relative optical density of proteins in control samples overexpressing wild-type STAT3 was set as 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control). i and j The relative luciferase activities in i MiaPaCa or j PANC-1 transfected with the luciferase reporter construct pGL-pdl1promo, together with a control void vector (pCMV-HA), or a plasmid expressing wild-type or indicated mutant STAT3. The relative luciferase activities in PDAC cells transfected with void vector were set to 1. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 compared with cells transfected with void vector. **p < 0.05 compared with cells transfected with plasmids expressing wild-type STAT3

To gain more insight into the properties of various STAT3 mutants, we analyzed the protein levels of PDL1 in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 transfected with various STAT3 overexpression constructs. In addition, we utilized the pGL-pdlpromo dual luciferase reporter plasmid to inspect the transcriptional activities of these STAT3 constructs in PDAC cells. We also measured the mRNA levels of STAT3 target genes ccnd1, bcl2l1, c-myc, and pdl1 in these cells by qPCR. In accordance with previous findings, we uncovered that the transcriptional activities, the PDL1 protein levels, as well as the mRNA levels of various STAT3 target genes, were positively correlated with pY705 STAT3 levels in PDAC cells, with STAT3-Y705D, STAT3-Y640F, and STAT3-S727A displaying higher capability in driving the expression of STAT3 target genes than STAT3-Y705F and STAT3-S727E in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells (Fig. 2a–j, Supplementary Fig. 4). Collectively, our data indicate that in pancreatic cancer cells, phosphorylation at the Y705 and S727 residuals of STAT3 appears to be mutually repulsive, with phosphorylation at one site attenuating that of the other. Furthermore, our results support the notion that STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705 residual determines STAT3 transcriptional activity in PDAC.

ATM may modulate STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation and subsequently STAT3 activity through STAT3 S727 residual in PDAC cells

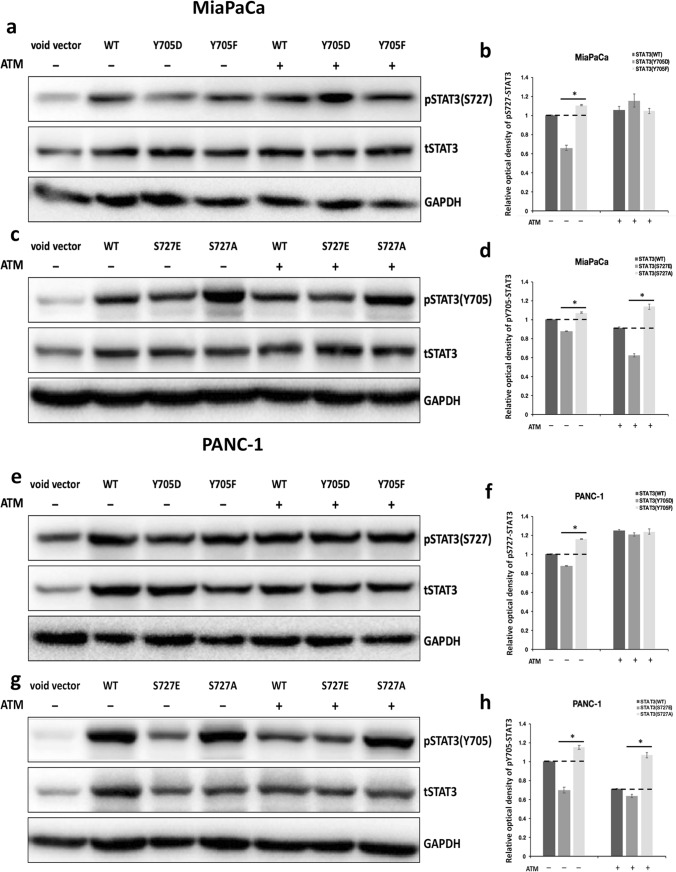

We next tried to examine how ATM, the chemical inhibitor of PKCι, differentially modulates the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 and S727 in PDAC cells.

First, MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells transfected with wild-type STAT3, STAT3-Y705D, or STAT3-Y705F were treated with vehicle solvent or 50 nM ATM for 24 h before being analyzed for their pS727 STAT3 levels. The immunoblotting results affirmed that in vehicle-treated PDAC cells overexpressing various STAT3 constructs, STAT3-Y705D suppressed, whereas STAT3-Y705F elevated STAT3 S727 phosphorylation when compared with wild-type STAT3. Nonetheless, ATM treatment increased the levels of pS727 STAT3 in PDAC cells overexpressing all three STAT3 constructs, and the levels of pS727 STAT3 were almost equivalent in ATM-treated cells overexpressing STAT3-Y705D and STAT3-Y705F (Fig. 3a, b, e, f), suggesting that ATM may enhance S727 phosphorylation independent of the status of Y705 STAT3 in PDAC cells.

Fig. 3.

The dephosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 residue caused by PKCι inhibitor ATM is affected by S727 status in PDAC. a and e Immunoblot analyses of the protein levels of STAT3 phosphorylated at S727, total STAT3, and GAPDH in a MiaPaCa and e PANC-1 transfected with void vector, or plasmid expressing STAT3-WT, -Y705D, or -705F with or without the presence of 50 nM ATM. b and f The relative optical intensity of pS727 STAT3 bands in a and e normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of pS727 bands in cells transfected with wild-type STAT3 without ATM treatment was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with samples overexpressing wild-type STAT3). c and g Immunoblot detection of pY705 STAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH levels in c MiaPaCa or g PANC-1 transfected with void vector, or plasmid expressing STAT3-WT, -S727E, or -S727A with or without 50 nM ATM treatment. d and h The relative optical density of pY705 STAT3 bands in c and g normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of pY705 bands in samples transfected with wild-type STAT3 without ATM treatment was set as 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with samples overexpressing wild-type STAT3)

Second, we examined the pY705 STAT3 levels in PDAC cells transfected with wild-type STAT3, STAT3-S727E or STAT3-S727A with or without the presence of ATM. We found that although ATM treatment decreased the pY705 STAT3 levels in PDAC cells expressing these three STAT3 constructs, the relative pY705 STAT3 levels in PDAC cells expressing wild-type, S727E, and S727A stayed the same before and after ATM treatment. The phospho-mimetic STAT3-S727E displayed reduced while the phospho-inactivating STAT3-S727A exhibited increased pY705 STAT3 levels compared with wild-type STAT3 despite the ATM treatment (Fig. 3c, d, g, h). This finding indicates that the ATM-mediated inhibition of Y705 phosphorylation is affected by the S727 status of STAT3 in PDAC cells. This data, together with the data obtained from STAT3-Y705F and -Y705A mutants, point to the possibility that ATM may block STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation via elevating STAT3 S727 phosphorylation in PDAC cells.

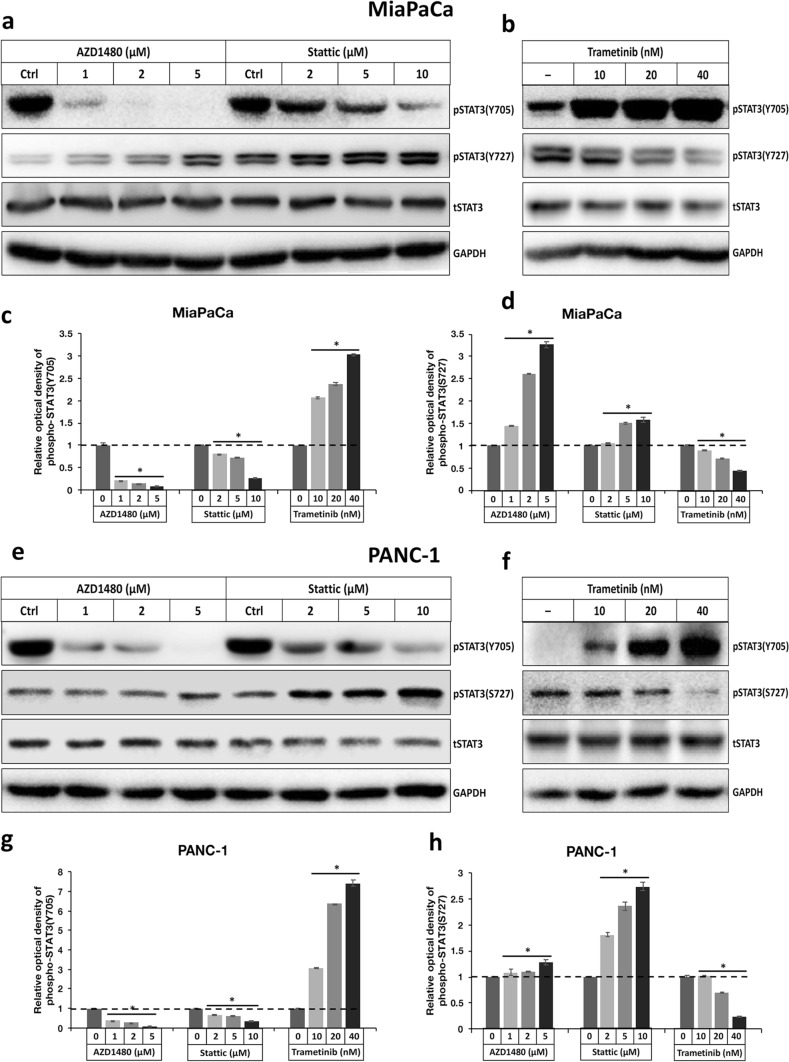

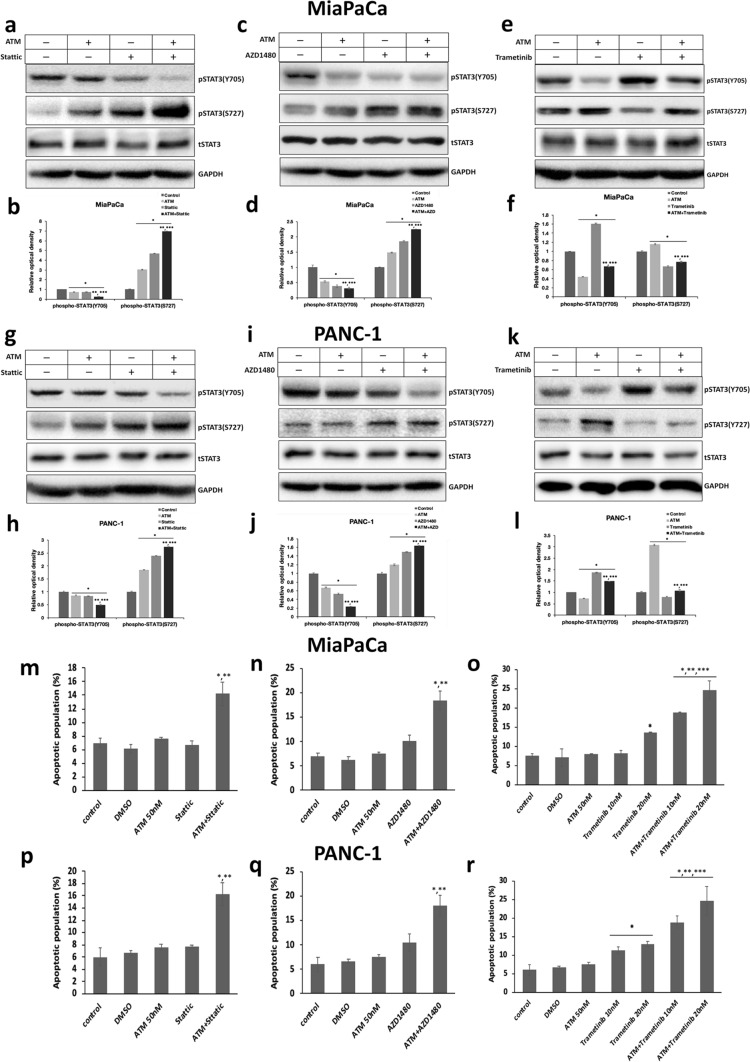

Two STAT3 inhibitors, Stattic and AZD1480, and the MEK inhibitor Trametinib, may modulate STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation and subsequently STAT3 activity through STAT3 S727 residual in PDAC cells

Recently, STAT3 inhibitors have emerged as promising candidate drugs for pancreatic cancer treatment which have obtained some encouraging results in clinical trials (Peisl et al. 2021). The activation of STAT3 elicited by MEK inhibitors has also been linked to the development of drug resistance in PDAC treatment (Nagathihalli et al. 2018). As a result, we chose two STAT3 inhibitors, Stattic and AZD1480, and one MEK inhibitor Trametinib, to test their effects on STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705 or S727. Our data revealed that both Stattic and AZD1480 could dose-dependently prohibit the Y705 phosphorylation, while enhancing the S727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in PDAC (Fig. 4a, c, d, e, g, h). Trametinib, on the other hand, was shown to induce Y705 phosphorylation while impeding S727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in PDAC in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4b, c, d, f, g, h). These data are in line with previous reports that Stattic and AZD1480 can restrict STAT3 activity through constraining its Y705 phosphorylation, whereas Trametinib may activate STAT3 by stimulating its Y705 phosphorylation. Besides, our results provide evidence that these cancer-suppressive compounds Stattic, AZD1480, and Trametinib are all capable of differentially phosphorylating Y705 and S727 of STAT3 in PDAC cells.

Fig. 4.

The differential phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 and S727 residues caused by STAT3 inhibitors Stattic, AZD 1480, and MEK inhibitor Trametinib in PDAC. a and b Immunoblot detection of pY705, pS727 STAT3, total STAT3 and GAPDH levels in MiaPaCa treated with various concentrations of a AZD1480, Stattic, and b Trametinib. c and d Comparison of the relative optical intensity of c pY705 and d pS727 STAT3 bands shown in a and b. The optical density of pY705 and pS727 STAT3 bands was normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical intensity of protein bands in control vehicle-treated samples was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control). e and f Immunoblot analyses of pY705, pS727 STAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH levels in PANC-1 treated with various concentrations of e AZD1480, Stattic, and f Trametinib. g and h Comparison of the relative optical intensity of (g) pY705 and (h) pS727 STAT3 bands shown in e and f. The optical density of pY705 and pS727 STAT3 bands was normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control)

To find out whether the differential phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 and S727 caused by Stattic, AZD1480, or Trametinib is inter-connected in PDAC, we then compared the status of S727 phosphorylation in MiaPaCa or PANC-1 overexpressing wild-type STAT3, STAT3-Y705D or STAT3-Y705F, as well as analyzing the pattern of Y705 phosphorylation in cells overexpressing wild-type STAT3, STAT3-S727E, or STAT3-S727A, with or without treatments by these drugs. Of interest, in our experiments, pS727 STAT3 levels became comparable in PDAC expressing STAT3-Y705D and -Y705F following treatment with Stattic, AZD1480, or Trametinib, suggesting that Stattic or AZD1480 elevate, and Trametinib hinders S727 phosphorylation regardless of the Y705 status in PDAC (Supplementary Fig. 5a and b, 6a and b, 7a and b, 8a and b). In contrast, the pattern of relative Y705 phosphorylation levels in PDAC cells expressing wild-type, STAT3-S727E or -S727A remained constant before and after treatment with Stattic, AZD1480, or Trametinib, insinuating that the Y705 phosphorylation of STAT3 exerted by these drugs is affected by S727 status in PDAC (Supplementary Fig. 5c and d, 6c and d, 7c and d, 8c and d). These results indicate that all of these drugs may modify Y705 phosphorylation via modulating S727 phosphorylation in STAT3.

PKCι inhibitor can act as a sensitizer to potentiate the anti-tumor effects of STAT3 inhibitors or MEK inhibitor through modulating STAT3 activity

In view of the fact that the PKCι inhibitor can modulate STAT3 activity by differentially phosphorylating Y705 and S727, we wondered whether PKCι inhibition could potentiate the anti-tumor effects of STAT3 inhibitors, or reverse the pro-survival effects that interfere with MEK inhibitor treatment in pancreatic cancer cells. To test this, we treated MiaPaCa and PANC-1 with 2 µM Stattic, 1 µM AZD1480, or 10 nM Trametinib, with or without the presence of 50 nM ATM, and compared the levels of STAT3 Y705 and S727 phosphorylation. Our immunoblotting results showed that when combined with ATM, the abilities of both STAT3 inhibitors (Stattic and AZD1480) to suppress Y705 and increase S727 phosphorylation were enhanced (Fig. 5a–d, g–j), whereas the induction of pY705 STAT3 by Trametinib was attenuated in PDAC (Fig. 5e, f, k, l).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PKCι with ATM enhances the apoptotic effects exerted by STAT3 inhibitors or MEK inhibitor via modulating differential phosphorylation of STAT3. a and g Immunoblot analyses of the protein levels of pY705, pS727 STAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH in a MiaPaCa and g PANC-1 treated with 50 nM ATM or 2 M Stattic alone, or ATM combined with Stattic. b and h Comparison of the relative optical density of pY705, pS727 STAT3 bands in a and g. The optical density of pY705 and pS727 STAT3 bands was normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. ***p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with Stattic). c and i Immunoblot analyses of pY705, pS727 STAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH levels in c MiaPaCa and i PANC-1 treated with 50 nM ATM or 1 M AZD1480 alone, or ATM along with AZD1480. d and j The relative optical density of pY705, pS727 STAT3 bands shown in c and i normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical intensity of control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. ***p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with AZD1480). e and k Immunoblot detection of the expression of pY705, pS727 STAT3, total STAT3, and GAPDH in e MiaPaCa and k PANC-1 treated with 50 nM ATM or 10 nM Trametinib alone, or ATM plus Trametinib. f and l The relative optical density of pY705, and pS727 STAT3 bands present in e and k normalized by total STAT3. The relative optical density of control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. ***p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with Trametinib). m and p The apoptotic population in m MiaPaCa or p PANC-1 treated with vehicle solvent (DMSO), 50 nM ATM, 2 M Stattic, or ATM combined with Stattic. Experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results. Data represent mean ± SD (*p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with Stattic). n and q The apoptotic population in n MiaPaCa or q PANC-1 treated with vehicle, 50 nM ATM, 1 M AZD1480, or ATM plus AZD1480. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results. Data represent mean ± SD (*p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with AZD1480). o and r The apoptotic population in o MiaPaCa or r PANC-1 treated with vehicle, 50 nM ATM, 10 nM or 20 nM Trametinib, or ATM coupled with Trametinib. Experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times with similar results. Data represent mean ± SD (*p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with vehicle. **p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with ATM. ***p < 0.05 compared with samples treated with Trametinib)

The apoptotic assay further confirmed that there was a 7% or 10.2% apoptotic population in MiaPaCa treated with low concentrations of Stattic (1 µM) or AZD 1480 (1 µM) alone, respectively, which were comparable with about 6% apoptotic population in control cells. 50 nM ATM caused a marginal 7.6% apoptotic population in MiaPaCa cells. In combination, ATM and Stattic caused apoptosis in 14.2% of the MiaPaCa cells, while ATM plus AZD 1480 increased the apoptotic population to 18.4% (Fig. 5m, n). Furthermore, ATM enhanced the apoptotic effect of Trametinib by elevating the apoptotic population from 8.1% and 13.4% in MiaPaCa treated with 10 nM and 20 nM Trametinib alone, to 18.8% and 24.6% after ATM addition, respectively (Fig. 5o). The same trend was visualized in PANC-1 cells, with combined treatment with ATM significantly strengthening the apoptotic effects of Stattic, AZD 1480, and Trametinib against PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5p, q, r).

Overall, our data demonstrate that the PKCι inhibitor, through modulating the activity of STAT3, can act as a sensitizer, to augment the anti-tumor effects of STAT3 or MEK inhibitors, or possibly counteract the drug resistance brought on by MEK inhibitor-mediated pY705 STAT3 in PDAC cells.

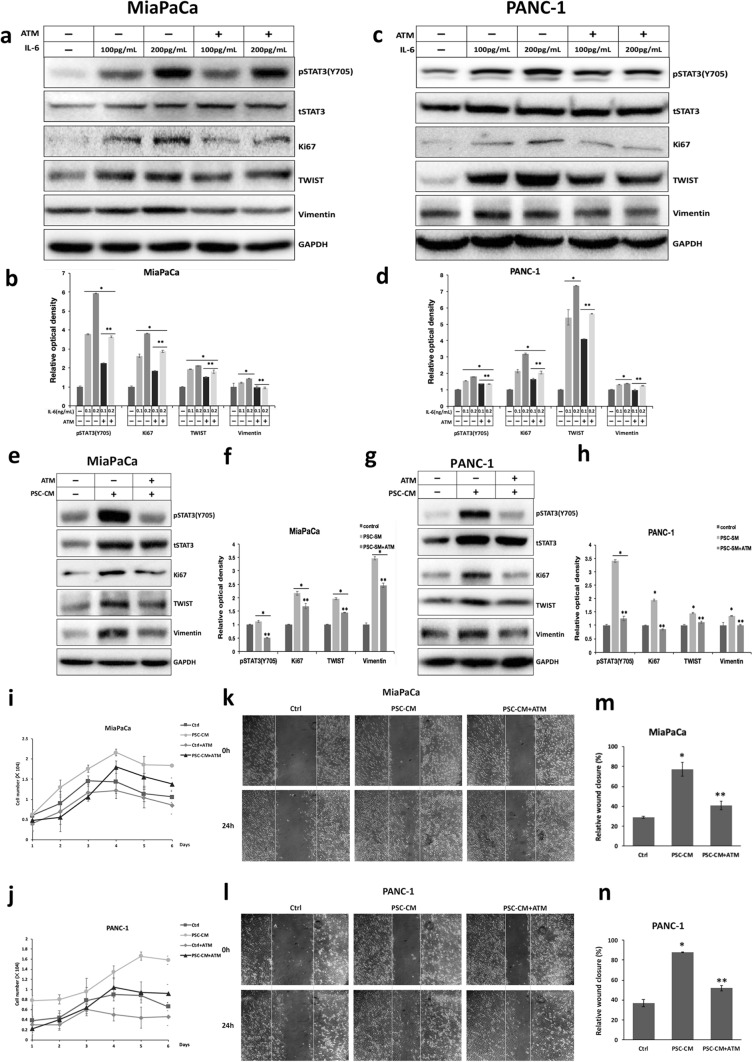

Suppression of PKCι obstructs the STAT3 activation induced by HPSC in PDAC, thereby restricting PDAC proliferation and invasion promoted by HPSC

It is established that the stromal response is critical in the development and progression of pancreatic tumor. IL-6 secreted by HPSC has been shown to promote the proliferation and invasion of PDAC via the IL-6-gp130-STAT3 signaling pathway, among other factors in the TME (Lesina et al. 2011). To scrutinize the potential impact of PKCι inhibitor on the stromal response of PDAC, we first treated MiaPaCa and PANC-1 with 100 or 200 pg/mL IL-6 in the presence or absence of ATM. In keeping with earlier studies, IL-6 treatment dose-dependently induced pY705 STAT3, accompanied by elevated expression of Ki67, a proliferation marker, as well as the Vimentin and Twist, two indicators of the EMT, in MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cells (Fig. 6a–d). However, we did not see a significant decrease in pS727 STAT3 levels in PDAC treated with IL-6 (data not shown), which could be attributed to an increase in total STAT3 levels induced by IL-6 in these cells (Fig. 6a, c). ATM treatment inhibited the increased phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 and the upregulation of Ki67, Vimentin, and Twist in response to IL-6, implicating that inhibition of PKCι in pancreatic cancer cells may restrain the proliferation and invasion incited by paracrine IL-6 in TME, most likely via regulating STAT3 (Fig. 6a, c, e, g).

Fig. 6.

PKCι inhibition prohibits the proliferation and migration provoked by HPSC, partially through IL-6. a and c Immunoblot detection of protein levels of pY705 STAT3, total STAT3, Ki67, TWIST, Vimentin and GAPDH in a MiaPaCa and c PANC-1 treated with various concentrations of IL-6, in the presence or absence of 50 nM ATM. b and d Comparison of the relative optical density of pY705 STAT3, Ki67, TWIST, and Vimentin bands illustrated in a and c. The optical intensity of the pY705 and pS727 STAT3 bands was normalized by total STAT3, whereas that of the others was normalized by GAPDH. The relative optical density of control protein bands was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control, ** p < 0.05 compared with samples not treated with ATM). e and g Immunoblot detection of protein levels of pY705 STAT3, total STAT3, Ki67, TWIST, Vimentin, and GAPDH in e MiaPaCa and g PANC-1 cultured in normal media or PSC-CM, in the presence or absence of 50 nM ATM. f and h Comparison of the pY705 STAT3, Ki67, TWIST, and Vimentin bands’ relative optical densities, as shown in e and g. Total STAT3 was used to normalize the optical density of the pY705 and pS727 STAT3 bands, whereas GAPDH was used to normalize that of the remaining bands. The relative optical density of proteins in normal-media-cultured cells was set to 1 (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with control, ** p < 0.05 compared with samples not treated with ATM). i and j Comparison of the growth of i MiaPaCa and j PANC-1 cells cultured in control media or PSC-CM with or without treatment with 50 nM ATM. Cells were counted in 3 wells and the results were expressed as mean ± SD. k and l Wound-healing analyses of k MiaPaCa and l PANC-1 cultured in control media or PSC-CM, with or without 50 nM ATM treatment. m and n The images in k and l were analyzed by ImageJ to assess the cell migration (n = 3, *p < 0.05 compared with cells cultured in control media, **p < 0.05 compared with cells cultured in PSC-CM)

Next, we cultured the two PDAC cell lines in conditioned media of HPSC (PSC-CM) and examined the status of STAT3 phosphorylation within these cells. We identified that in PDAC cells cultured in HPSC supernatant, phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 was enhanced, as were Ki67, Vimentin, and Twist levels, which were impeded by the addition of 50 nM ATM (Fig. 6e–h). Moreover, the expression of total STAT3 was substantially upregulated in PDAC cultured in PSC-CM (Fig. 6e, g). We also found that neutralizing IL-6 in PSC-CM with antibody could partially compromise the effects of PSC-CM on elevating pY705 STAT3, Ki67, Twist, and Vimentin levels (data not shown), indicating that IL-6, among other soluble factors in PSC-CM, contributes to STAT3 upregulation and activation, thereby promoting the progression of PDAC.

Consistent with the above-mentioned immunoblotting results, our proliferation assays demonstrated that MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cultured in PSC-CM manifested augmented growth potential as compared with control cells cultured in regular media. The addition of 50 nM ATM to PSC-CM reduced the growth rates of these PDAC cells to near-control levels (Fig. 6i, j). Furthermore, the wound-healing assay revealed that MiaPaCa and PANC-1 cultured in PSC-CM had much higher mobility than control cells, which was repressed by treatment with 50 nM ATM (Fig. 6k–n). Altogether, these experiment results corroborate that inhibiting PKCι with ATM is capable of suppressing the stromal responses elicited by HPSC, at least partially through STAT3, in pancreatic cancer cells.

Discussion

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most common type of pancreatic cancer, accounting for more than 90% of all cases (Adamska et al. 2017). In 70–95% of PDAC, hyperactive KRAS mutations are present (Bardeesy et al. 2002). Although pharmacological targeting of KRAS has been attempted for decades and a small molecule inhibitor against mutant KRAS has recently emerged as a promising candidate for PDAC treatment (Janes et al. 2018), uncertainty about its clinical outcomes continues to impel efforts to unearth novel downstream effectors of oncogenic KRAS signaling for the treatment of this aggressive malignancy.

From previous studies, we and others have revealed the essential roles that PKCι plays in sustaining the transformed cell growth and mediating the crosstalk between the TME and PDAC (Inman et al. 2022; Scotti et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2018, 2020; Yang et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021). Notably, we identified that PKCι is capable of modulating the activity of STAT3, a transcription factor that serves as a hub to integrate a vast array of intra- and inter-cellular signaling, thereby promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis (Philips et al. 2022). It has been defined that within cells, the canonical STAT3 signaling pathway involves the phosphorylation of STAT3 Tyrosine 705 and subsequent dimerization and nuclear localization of this TF, allowing it to regulate the transcription of a multitude of gene networks dictating cell proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, stemness, chemoresistance, carbon metabolism, inflammation and immune responses (Schindler et al. 2007; Shuai et al. 1994). Moreover, unphosphorylated STAT3 has been shown to translocate to the nucleus to regulate NF-B-associated transcriptions (Yang et al. 2007), and phosphorylation of STAT3 at another residual Serine 727 has been shown to enhance the transcriptional activity of nuclear pY705 STAT3, or facilitate the transcriptional elongation of STAT3 target genes (Balic et al. 2019; Wen et al. 1995). Additionally, STAT3 phosphorylated at S727 can translocate to mitochondria to help maintain the redox homeostasis and enhance the aerobic glycolysis in Ras-transformed cells (Alhayyani et al. 2022; Gough et al. 2009). Other posttranslational modifications (PTMs), including acetylation, ubiquitination, methylation, S-glutathionylation, and SUMOylatin, have also been implicated in regulating STAT3 transcriptional outputs (Guanizo et al. 2018; Huynh et al. 2019; Tesoriere and Dinarello 2021). These discoveries raise the possibility that various PTMs may coordinate to impact the subcellular distribution and function of STAT3, resulting in highly context-dependent and cell-type-specific cellular consequences. Therefore, deciphering the regulation and functions of various STAT3 PTMs is crucial for understanding the full range of STAT3’s important, and sometimes paradoxical, roles in diverse physiological processes.

The precise function of STAT3 in pancreatic tumors is rather controversial. A multitude of studies demonstrate that STAT3 phosphorylated at Y705, either constitutively or in response to a variety of external stimuli from the TME, such as IL-6 or IL-22, provokes the development of pancreatic cancers (Corcoran et al. 2011; Gruber et al. 2016; He et al. 2018; Lesina et al. 2011; Nagathihalli et al. 2015). However, some recent reports display evidence that STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation delays the onset of KRAS-driven tumorigenesis by maintaining the epithelial identity and differentiation in pancreatic and lung cancers (D’Amico et al. 2018). These conflicting results suggest that in pancreatic tumors of distinct stages or with different TME, STAT3 may engage various signaling pathways to generate disparate cellular effects.

In this work, in an attempt to unravel how PKCι modulates the activity of STAT3 in PDAC, we discovered that oncogenic PKCι enhances the phosphorylation of Y705 STAT3, while concomitantly muffling the phosphorylation of S727 STAT3 in PDAC. Further investigation utilizing a series of phospho-mimetic or phospho-deficient STAT3 mutants divulged that the phosphorylation at Y705 and S727 appears to be mutually antagonistic within PDAC cells. Next, by combining these STAT3 mutants with a pharmacological inhibitor of PKCι (ATM), we determined that the diminution of pY705 STAT3 caused by PKCι inhibition is affected by the status of S727, because the level of pY705 in PDAC cells expressing STAT3-S727E (by analog, pS727 STAT3) is always lower, and that in cells expressing phospho-deficient STAT3-S727A is higher compared with wild-type STAT3 expressing cells, before and after ATM treatment. In contrast, while STAT3 Y705D (by analog, pY705 STAT3) expression represses and phospho-deficient STAT3 Y705F expression intensifies S727 phosphorylation in comparison to wild-type STAT3, ATM treatment increases the amount of pS727 STAT3 in these cells to nearly the same level, implying a Y705 phosphorylation-independent fashion in S727 phosphorylation mediated by PKCι inhibition. Previously, the reversely correlated phosphorylation of Y705 and S727 has been identified in various cell types. In liver carcinoma HepG2 cells, pS727 is shown to be able to activate the phosphatase TC45 to de-phosphorylate Y705 in STAT3, leading to pY705-SH2 dissociation (Wakahara et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2020). Notably, in a mouse model of KRAS-driven lung and pancreatic cancer, constitutively activating STAT3 by Y705 phosphorylation impedes tumor formation, whereas a phospho-mimetic mutant of S727 mirrors the loss of pY705 STAT3 in promoting tumorigenesis (D’Amico et al. 2018). Furthermore, in KRAS mutant lung cancers, pY705 STAT3 has been shown to be tumor-suppressive, whilst pS727 STAT3 is indispensable for tumor cell proliferation (Alhayyani et al. 2022; Grabner et al. 2015). The inhibition of MEK/Erk, a downstream effector of RAS signaling capable of phosphorylating S727 STAT3, has also been shown to immediately activate STAT3 by Y705 phosphorylation in PDAC (Kuroki et al. 1999; Nagathihalli et al. 2018). These studies all point to reversely related functions between Y705 and S727 phosphorylation in KRAS mutant tumors. Here, our data offer clear evidence that the phosphorylation of Y705 and S727 STAT3 is antagonistic in KRAS mutant PDAC cells. This finding sheds light on a possible switch that may enable STAT3 to exhibit discrete, and sometimes opposing, cellular effects in response to various intra- and extracellular stimuli, and it entails further research into how various PTMs are coordinated to control STAT3 function, as well as its physiological or pathological implications in the development of PDAC or other Ras-transformed malignancies.

Given that multiple studies have demonstrated the oncogenic roles of constitutively active STAT3 in provoking the progression, or reprogramming the TME of pancreatic cancers, STAT3 has become a therapeutic target for developing novel PDAC treatment regimens (Hu et al. 2021; Li et al. 2022; Peisl et al. 2021; Sahu et al. 2017; Sharma et al. 2014). Furthermore, STAT3 activation has been linked to chemoresistance elicited by a variety of antitumor drugs, including MEK inhibitors (Nagathihalli et al. 2018; Sahu et al. 2017). Therefore, STAT3 inhibitors have been assessed for their antitumor effects against PDAC, either alone or in combination with other pharmacological agents, with some clinical trials exhibiting favorable results (Chen et al. 2021; Datta et al. 2022; Dosch et al. 2020; Sahu et al. 2017). Considering that our experimental data have pinpointed PKCι as a modulator of the STAT3 activity, we further assessed the combined antitumor effects of PKCι inhibitor (ATM) with STAT3 inhibitors (Stattic or AZD1480), or MEK inhibitor (Trametinib), to see whether PKCι suppression can strengthen the efficacy of these chemical agents, or overcome drug resistance inspired by MEK inhibitors. In line with previous findings, STAT3 inhibitors Stattic and AZD1480 prohibit, while MEK inhibitor Trametinib promotes the pY705 STAT3, with concurrent increment and reduction in pS727 STAT3 levels in PDAC cells, respectively. These results implicate that all of these agents cause differential phosphorylation of STAT3 Y705 and S727 in PDAC. Interestingly, using a series of STAT3 mutants, we found that like ATM, Stattic, AZD1480, and Trametinib all appear to modify the STAT3 Y705 phosphorylation in a S727 phosphorylation-dependent manner, but not vice versa. For Trametinib, these findings are consistent with the earlier discovery that MEK can directly phosphorylate STAT3 S727. Hence it stands to reason that Trametinib disrupts the S727 phosphorylation caused by MEK, increasing Y705 phosphorylation. For Stattic and AZD1480, these results raise the possibility that other molecules, such as phosphatases, are involved in the differential phosphorylation of Y705 and S727 mediated by these chemical agents. As regards the antitumor activity, ATM is shown to amplify the apoptotic population induced by Stattic, AZD1480 and Trametinib, probably through synergizing the inhibitory effects of Stattic and AZD1480 on pY705 STAT3, or by pressing the elevated pY705 STAT3 levels induced by Trametinib in PDAC. Moreover, we identified that in PDAC cells cultured in the supernatant of HPSC, which partially mimics the microenvironment of pancreatic cancers, the greatly enhanced pY705 STAT3 in response to various soluble agents including IL-6 is partially abrogated by ATM treatment, resulting in impaired growth and invasion in these cells. Collectively, these data affirm that PKCι inhibitor, through suppressing pY705 STAT3, can act as a sensitizer to boost the antitumor effects of other STAT3 inhibitors or MEK inhibitors, or possibly to offset the chemoresistant effect caused by MEK inhibitors. In addition, it can mitigate the stromal response induced by the TME of PDAC. As a result, PKCι inhibition provides a more effective therapeutic regimen for PDAC treatment.

Conclusions

Taken together, we identify in this study that in KRAS-mutant PDAC cells, PKCι can activate the transcriptional activity of STAT3 through differentially modulating STAT3 phosphorylation at Y705 and S727, so to support the dysregulated growth and survival in cancer cells. Inhibition of PKCι amplifies the antitumor effects of STAT3 inhibitors and MEK inhibitors, establishing PKCι as a prospective therapeutic target for developing novel and more effective PDAC treatment options.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PKCι

Protein kinase C isoform ι

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- STAT3

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TF

Transcription factor

- HPSC

Human pancreatic stellate cells

- ATM

Aurothiomalate

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- PTM

Posttranslational modification

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China 81472555.

Data availability

All data underlying this article are present in the paper and its online supplementary material. Requests for any material in this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Junli Wang, Sijia Weng and Yue Zhu have contributed equally to this work.

References

- Adamska A, Domenichini A, Falasca M, et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: current and evolving therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7):1338. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhayyani S, McLeod L, West AC, Balic JJ, Hodges C, et al. Oncogenic dependency on STAT3 serine phosphorylation in KRAS mutant lung cancer. Oncogene. 2022;41(6):809–823. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic JJ, Garama DJ, Saad MI, Yu L, West AC, et al. Serine-phosphorylated STAT3 promotes tumorigenesis via modulation of RNA polymerase transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2019;79(20):5272–5287. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardeesy N, DePinho RA, et al. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(12):897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Cen L, Kohout J, Hutzen B, Chan C, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation is associated with bladder cancer cell growth and survival. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:78. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Bian A, Yang L, Yin X, Wang J, et al. Targeting STAT3 by a small molecule suppresses pancreatic cancer progression. Oncogene. 2021;40(8):1440–1457. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran RB, Contino G, Deshpande V, Tzatsos A, Conrad C, et al. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71(14):5020–5029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico S, Shi J, Martin BL, Crawford HC, Petrenko O, et al. STAT3 is a master regulator of epithelial identity and KRAS-driven tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2018;32(17–18):1175–1187. doi: 10.1101/gad.311852.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta J, Dai X, Bianchi A, Silva IDC, Mehra S, et al. Combined MEK and STAT3 inhibition uncovers stromal plasticity by enriching for cancer-associated fibroblasts with mesenchymal stem cell-like features to overcome immunotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(6):1593–1612. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosch AR, Dai X, Reyzer ML, Mehra S, Srinivasan S, et al. Combined Src/EGFR Inhibition targets STAT3 signaling and induces stromal remodeling to improve survival in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;18(4):623–631. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-19-0741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields AP, Frederick LA, Regala RP. Targeting the oncogenic protein kinase Ciota signalling pathway for the treatment of cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35(Pt 5):996–1000. doi: 10.1042/BST0350996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough DJ, Corlett A, Schlessinger K, Wegrzyn J, Larner AC, et al. Mitochondrial STAT3 supports Ras-dependent oncogenic transformation. Science. 2009;324(5935):1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1171721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabner B, Schramek D, Mueller KM, Moll HP, Svinka J, et al. Disruption of STAT3 signalling promotes KRAS-induced lung tumorigenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6285. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(4):281–294. doi: 10.1038/nrc2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber R, Panayiotou R, Nye E, Spencer-Dene B, Stamp G, Behrens A. YAP1 and TAZ control pancreatic cancer initiation in mice by direct up-regulation of JAK-STAT3 signaling. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(3):526–539. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guanizo AC, Fernando CD, Garama DJ, Gough DJ. STAT3: a multifaceted oncoprotein. Growth Factors. 2018;36(1–2):1–14. doi: 10.1080/08977194.2018.1473393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Wu J, Shi J, Huo Y, Dai W, et al. IL22RA1/STAT3 signaling promotes stemness and tumorigenicity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(12):3293–3305. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X, Wang W. The JAK/STAT signaling pathway: from bench to clinic. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):402. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00791-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh J, Chand A, Gough D, Ernst M. Therapeutically exploiting STAT3 activity in cancer - using tissue repair as a road map. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019;19(2):82–96. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman KS, Liu Y, Scotti ML, Leitges M, Krishna M, et al. Prkci regulates autophagy and pancreatic tumorigenesis in mice. Cancers (basel) 2022;14(3):796. doi: 10.3390/cancers14030796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes MR, Zhang J, Li LS, Hansen R, Peters U, et al. Targeting KRAS mutant cancers with a covalent G12C-specific inhibitor. Cell. 2018;172(3):578–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Inokuchi J, Eto M, Murata M, Kang J-H. Protein kinase C (PKC) isozymes as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer. Cancers (basel) 2022;14(21):5425. doi: 10.3390/cancers14215425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MW, Saadalla A, Ewida AH, Al-Katranji K, Al-Saoudi G, et al. The STAT3 inhibitor pyrimethamine displays anti-cancer and immune stimulatory effects in murine models of breast cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother: CII. 2018;67(1):13–23. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2057-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki M, O'Flaherty JT. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK)-dependent and ERK-independent pathways target STAT3 on serine-727 in human neutrophils stimulated by chemotactic factors and cytokines. Biochem J. 1999;341(PT 3):691–696. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesina M, Kurkowski MU, Ludes K, Rose-John S, Treiber M, et al. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(4):456–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Jiang W, Dong S, Li W, Zhu W, Zhou W. A novel insight for anticancer therapy of pancreatic cancer. Biomolecules. 2022;12(10):1450. doi: 10.3390/biom12101450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT, Wooten MW, et al. Of the atypical PKCs, Par-4 and p62: recent understandings of the biology and pathology of a PB1-dominated complex. Cell Death Diff. 2009;16(11):1426–1437. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagathihalli NS, Castellanos JA, Shi C, Beesetty Y, Reyzer ML, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, mediated remodeling of the tumor microenvironment results in enhanced tumor drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1932–1943. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagathihalli NS, Castellanos JA, Lamichhane P, Messaggio F, Shi C, et al. Inverse correlation of STAT3 and MEK signaling mediates resistance to RAS pathway inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(21):6235–6246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono Y, Fuji T, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Igarashi K, et al. The structure, expression, and properties of additional members of the protein kinase C family. J Biol Chem. 1998;263(14):6927–6932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisl S, Mellenthin C, Vignot L, Gonelle-Gispert C, Bühler L et al (2021) Therapeutic targeting of STAT3 pathways in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a systematic review of clinical and preclinical literature PLoS One 16(6):e0252397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Philips RL, Wang Y, Cheon H, Kanno Y, Gadina M, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway at 30: much learned, much more to do. Cell. 2022;185(21):3857–3876. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T, et al. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(28):20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu N, Chan E, Chu F, Pham T, Koeppen H, et al. Cotargeting of MEK and PDGFR/STAT3 pathways to treat pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(9):1729–1738. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotti ML, Bamlet WB, Smyrk TC, Fields AP, Murray NR, et al. Protein kinase Ciota is required for pancreatic cancer cell transformed growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(5):2064–2074. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma NK, Shankar S, Srivastava RK. STAT3 as an emerging molecular target in pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;4:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shuai K, Horvath CM, Huang LH, Qureshi SA, Cowburn D, et al. Interferon activation of the transcription factor Stat91 involves dimerization through SH2-phosphotyrosyl peptide interactions. Cell. 1994;76(5):821–828. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Shishodia G, Koul HK. Pancreatic cancer: genetics, disease progression, therapeutic resistance and treatment strategies. J Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2021;7:60. doi: 10.20517/2394-4722.2021.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto S, Ushijima K, Kawano K, Yamaguchi T, Terada A, et al. Expression of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 predicts poor prognosis in cervical squamous-cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(6):967–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesoriere A, Dinarello A. The Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in STAT3 Biological Activities and Functions. Biomedicines. 2021;9(8):956. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9080956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakahara R, Kunimoto H, Tanino K, Kojima H, Inoue A, et al. Phospho-Ser727 of STAT3 regulates STAT3 activity by enhancing dephosphorylation of phospho-Tyr705 largely through TC45. Genes Cells. 2012;17(2):132–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2011.01575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Wei D, Zhang H, Chen J, Zhang D, et al. PKCι and YAP1 are crucial in promoting pancreatic tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2018;9(67):32736–32750. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Zhang H, Yang J, Li Z, Wang Y, et al. Mu-KRAS attenuates Hippo signaling pathway through PKCι to sustain the growth of pancreatic cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(1):408–420. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Z, Zhong Z, Darnell JE. Maximal activation of transcription by Stat1 and Stat3 requires both tyrosine and serine phosphorylation. Cell. 1995;82(2):241–250. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, et al. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFkappaB. Genes Dev. 2007;21(11):1396–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Kunimoto H, Katayama B, Zhao H, Shiromizu T, et al. Phospho-Ser727 triggers a multistep inactivation of STAT3 by rapid dissociation of pY705-SH2 through C-terminal tail modulation. Int Immunol. 2020;32(2):73–88. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxz061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wang J, Zhang H, Li C, Chen C, et al. Transcription factor Sp1 is upregulated by PKCι to drive the expression of YAP1 during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2021;42(3):344–356. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgaa113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying H, Dey P, Yao W, Kimmelman AC, Draetta GF, et al. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2016;30(4):355–385. doi: 10.1101/gad.275776.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhu Y, Wang J, Weng S, Zuo F, et al. PKCι regulates the expression of PDL1 through multiple pathways to modulate immune suppression of pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2021;86:110115. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data underlying this article are present in the paper and its online supplementary material. Requests for any material in this study should be directed to the corresponding author.