Abstract

Background

Social isolation is a global public health threat. Veterans are particularly at risk for social isolation due to high rates of comorbid physical and mental health problems. Yet, effective interventions are limited.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of CONNECTED, a novel, transdiagnostic intervention to reduce social isolation that includes individual and group components and is delivered by peers via telehealth. Secondary objectives were to identify appropriate outcome measures and explore preliminary intervention effects.

Methods

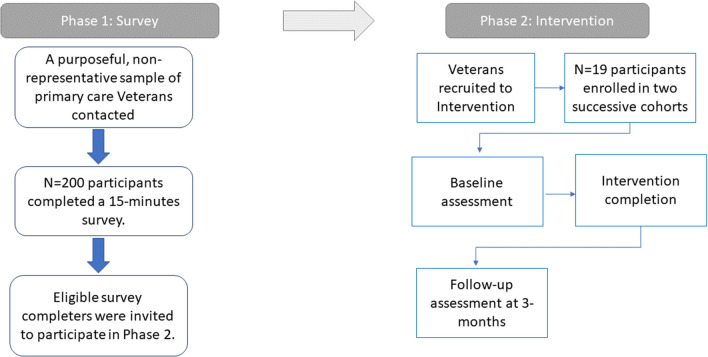

This was a two-phase study. In Phase 1, to evaluate study feasibility, we surveyed 200 veterans to assess prevalence of social isolation and their interest in social connectedness interventions. In Phase 2, we employed a mixed-methods, pre-post study design in which we piloted CONNECTED with 19 veterans through 2 successive cohorts to further assess feasibility, to evaluate acceptability, and to explore preliminary effectiveness. Quantitative analyses involved descriptive and bivariate analyses as well as multivariate modeling. Qualitative interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

For Phase 1, 39% of veterans surveyed were socially isolated. Participants who were ≤ 55 years old, caregivers, and those who experienced unmet social needs were more likely to report social isolation. Over 61% expressed interest in VA programs to reduce social isolation. For Phase 2, the pilot intervention, recruitment rate was 88% and the enrollment rate was 86%. Retention rates for the two cohorts were 80% and 50%, respectively, and satisfaction rates among intervention completers were 100%. Results also showed statistically significant improvements in social isolation (+ 5.91, SD = 4.99; p = .0028), social support (+ 0.74, SD = 1.09; p = .03), anxiety (-3.92, SD = 3.73; p = .003), and depression (-3.83, SD = 3.13; p = .001). Results for the other measures were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

CONNECTED is a feasible and acceptable intervention and is likely to be an effective tool to intervene on social isolation among veterans.

Supplementary Information:

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-023-08387-x.

KEY WORDS: social isolation, social determinants of health, peers, veterans, healthcare system.

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Social isolation is a critical public health concern and a major risk factor for poor health1–7. Unlike loneliness, which refers to perceptions of social isolation and can occur in the presence or absence of social isolation, social isolation is an objective state characterized by the absence or paucity of social connections8, 9. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, public health concerns about social isolation were growing globally10. Moreover, since the COVID-19 outbreak, rates of social isolation in the U.S. have increased11, 12. Furthermore, the negative impacts of social isolation on health are substantive and well-documented. Adults who are socially isolated report worse physical health13, have more physician visits14, and experience higher rates of mortality than those who are not.1 Social isolation also contributes to cardiovascular diseases, dementia, depression, suicidal ideation, and premature death14, 15.

Compared to the general population, veterans are more vulnerable to factors that contribute to social isolation, placing them at higher risk. They are more likely to be divorced, to live alone16, 17, to be homeless 18, and to have a mental illness19. Among veterans, social isolation is associated with depression, low social functioning, and suicidality20, 21. Socially isolated veterans are up to 5 times more likely to be hospitalized for mental health conditions compared to those with low-levels of social isolation22. Conversely, social connections are associated with lower depression and fewer mental health visits among veterans 20, 23. Data about the prevalence of social isolation among veterans are scarce, and existing studies are limited to specific subgroups of veterans24. One study of older veterans (65 years of age or older) who were Medicare beneficiaries estimated that 1 in 5 were socially isolated 24. In 2022, the Annual Warrior Project reported that 78% of veterans surveyed were socially isolated, a sharp increase from the 2019 rate of 43%25, 26.

Given the well-documented deleterious effects of social isolation, effective strategies to mitigate these effects are needed. Indeed, social isolation has been identified as a modifiable negative social determinant of health, (SDH)27–29. Despite this, most patients are not asked about social isolation in healthcare settings, even though patients have expressed openness to screening and desire for assistance with social isolation30. Although several social isolation interventions have been developed, robust data on their effectiveness are limited31.Additionally, most social isolation reduction programs were developed with samples that lack racial, age-, and gender-diversity15, 27–29. To address this gap, we developed the Increasing Veterans’ Social Engagement and Connectedness (CONNECTED) program—a transdiagnostic intervention aimed at reducing social isolation for patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) healthcare system.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

This was a two-phase study conducted from February to September 2022 in primary care clinics at a large Midwestern Veterans Affairs Medical Center. In phase 1, study feasibility, we surveyed patients to estimate: a) prevalence of social isolation, and b) interest in participating in an intervention to address social isolation. In Phase 2, we piloted the intervention to evaluate its feasibility and acceptability using a mixed-methods approach. All participants provided verbal informed consent prior to participation. The study was approved by the local university Institutional Review Board and the Veterans Affairs Medical Center. It followed the standard CONSORT extension guidelines for pilot feasibility trials32, which was adapted for this non-randomized feasibility study, and the Template Intervention Description and Replication Checklist (Appendix 1).

Phase 1: Survey to Establish Study Feasibility

Study Setting, Sample, and Recruitment Procedures

In phase 1, we sought to a) recruit a purposive, non-representative sample of 200 participants to evaluate the feasibility of our recruitment methods and b) identify participants for the Phase 2 pilot intervention. We generated a list of potential participants using Veterans Health Administration (VHA) administrative data. Eligibility criteria included completion of a primary care visit at the medical center within 6 months prior to study enrollment and availability of an email address. We emailed potential participants, followed by a phone call, inviting them to complete a brief, 15-min survey over the phone with a research assistant about their experiences with social isolation. To ensure that we captured the views of female and minoritized veterans, we oversampled these groups. We contacted 50 Veterans at a time, starting with those who had the most recent primary care visits, and continued recruitment until we had 200 surveys completed. Participants were offered $5 gift card upon survey completion and a chance to win an additional $50 gift card in a lottery.

Measures

Social isolation was measured with the Lubben Social Isolation Network Scale (LSNS-6). The LSNS-6 is a validated, 6-item, self-reported measure that evaluates the frequency, size, and closeness of contact for respondents’ social networks. Items are scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 to 5, with higher values representing more robust social networks. Scores range from 0 to 30, with ≤ 12 indicating social isolation33. The scale has been used with a variety of ages, racial groups, and settings34–36. The LSNS-6 has strong internal consistency (α = 0.83)33. Other measures included questions about participants’ views of social isolation, experiences of unmet social needs (food insecurity, housing instability, and lack of transportation), and interest in social isolation reduction interventions. (Survey is included in Appendix 2).

Phase 2: Intervention Pilot

Sample and Recruitment Procedures

The objective for Phase 2 was twofold: a) to evaluate feasibility and acceptability of the CONNECTED intervention, and b) to examine potential, preliminary effectiveness of CONNECTED to inform the design of an effectiveness trial. We supplemented the quantitative data with qualitative interviews about participants’ experiences with the intervention and its perceived effects.

To be eligible, participants must a) have reported social isolation (i.e., a score of ≤ 12 on the LSNS-6) in the Phase 1 survey, b) expressed interest in participating in social isolation reduction interventions, and c) be available to meet during group sessions. Participants completed outcome assessments at baseline and 3 months and received $25 for the baseline and $50 for the 3-month assessment. Assessments took average 30 min to complete. Figure 1 presents the timeline of data collection and intervention activities.

Figure 1.

CONNECTED Study timeline of data collection and intervention activities.

CONNECTED Intervention

Grounded in Wang and colleagues’ social isolation conceptual model37, CONNECTED is a manualized intervention delivered by VHA peer support specialists (peers) via telehealth through weekly individual and group sessions over 3 months. CONNECTED has the following components: a) peer support, an evidence-based approach that includes person-centered assessment of factors driving social isolation to foster patient self-efficacy38; b) psychosocial interventions to address social isolation; and c) navigation, a well-established care model that addresses SDH by connecting individuals to resources that meet their health and psychosocial needs39 to expand their social networks and increase social engagement. Through these intervention components, we aimed to improve the quantity (e.g., social network size), structure (e.g., diverse sources of social connections), function (e.g., perceived support), and quality (e.g., positive social bonds) of participants’ social relationships.

CONNECTED consisted of 2.5 peer contact hours per week, for a total of 30 h. Group sessions lasted 90-min and were delivered via VA TEAMS. Individual sessions lasted 30–60 min and occurred through TEAMS or phone, based on participants’ preferences. Individual sessions sought to engage patients, address barriers to group participation, create opportunities for socialization, and facilitate self-efficacy for social engagement and achievement of social connectedness goals. Group sessions drew from elements of cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and acceptance and commitment therapy to target psychosocial barriers to social engagement and support development of skills to increase social connectedness. Sessions incorporated didactics, hands-on activities, small-group discussions, and opportunities for social engagement. An overview of group content is included in Supplement Table 1. CONNECTED also included a patient workbook with worksheets and educational materials that reinforced group lessons. Peers provided individualized navigation services for social resources within and outside the VHA, facilitated by collabortation with the VHA Whole Health Program and Recreational Art Therapy Services, as well as several community organizations. Two peers (one Black male, one White female), who completed over 40 h of intervention-specific training, delivered the intervention. Some peer-led social and community activities were conducted in-person as part of the navigation component of the intervention. Each participant was assigned a peer for the individual sessions based on preference (e.g., shared gender or racial identity, or schedule).

Phase 2 measures

Feasibility and Acceptability

Study feasibility was determined by the ability to recruit, enroll, and retain participants, and administer study procedures. Feasibility of the CONNECTED intervention was assessed based on peers’ delivery of the intervention with fidelity to study protocol, and participants’ treatment adherence (number of sessions completed). To assess fidelity, two clinical psychologists observed in-vivo one randomly selected group session and completed the CONNECTED fidelity scale. The scale assessed fidelity at the peer level and included evaluation of session content and peers’ clinical competence. Scores ranged from 0–20, with a score of 16 (80%) indicating fidelity. Feedback based on fidelity assessments was provided to peers to refine intervention delivery and reinforce training.

Intervention acceptability was assessed quantitatively via survey and qualitatively through interviews across three domains from the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability: affective attitude (how participants feel about the intervention), burden (challenges of the intervention), and perceived effectiveness (perceived usefulness of the intervention)40, 41. We assessed satisfaction with an 5-item survey developed for this study (see Supplemental Appendix A), which evaluated satisfaction with the peers, specific components of the intervention, and the intervention overall. All items were ranked on a 5-point Likert Scale, ranging from 1 = very satisfied to 5 = very dissatisfied. Our pre-determined benchmark for acceptability was to have 80% of participants reporting satisfaction with the program. The qualitative interviews were guided in part by the health equity implementation framework42 and included questions about a) experiences with the intervention; b) views of the peers; and c) views of the intervention, its components, and perceived impact (See supplemental Appendix B). Interviews, which lasted 30–45 min, were conducted via video by a research assistant. They were audio-recorded and transcribed for analysis.

Preliminary Effects of the Intervention

We administered several measures to identify appropriate patient-centered outcomes for the future trial and to evaluate potential effectiveness of CONNECTED. These included measures of social isolation, loneliness, depression, anxiety, and quality of life. Social isolation was assessed with the Lubben Social Network Survey (LSNS-6), described above33. Loneliness was measured with the UCLA Loneliness Scale -6 (ULS-6)43. It is scored on a 4-point Likert Scale, ranging from 1 to 4, with lower scores indicating less loneliness. The ULS-6 and has demonstrated internal consistency (α = 0.89—0.94) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.73)43. Anxiety was assessed with the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale, a validated 7-item self-report measure that has shown high internal consistency (α = 0.89), and good sensitivity. A score of 10 or higher indicates moderate to severe anxiety44. Depression was measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a 9-item scale with high internal consistency (α = 0.89) and good sensitivity. A score of 10 or higher indicates moderate to severe depression45. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was included to assess perceived adequacy of social support. The scale is measured on a 5-point Likert Scale, with a score of 3 or higher indicative of moderate to high support 46. The Life Engagement Scale (LET) is a 6-item survey that measures the extent to which a person engages in activities that are valued; the scale has high internal consistency (α = 0.80)47. Items are measured on a 5-point Likert Scale with higher scores indicative of higher engagement. Quality of Life was assessed with the Veteran Rand Health Survey (VR-12), a 12-item self-administered questionnaire that assesses perceptions of general physical, social, and mental health functions48. We supplemented the quantitative data with qualitative interviews about experiences with the intervention and its perceived impacts. We also collected demographic data at baseline and conducted chart reviews to collect patients’ mental health diagnoses at the end of the study.

DATA ANALYSES

Quantitative Data

Basic descriptive statistics for patients’ characteristics were calculated as means (standard deviations) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Bivariate analyses were performed using Student’s t-tests and Fisher’s Exact tests (Mantel–Haenszel tests were used for ordinal/ranked data), respectively. Fisher’s Exact tests were used due to many analyses having small expected cell counts, but all such analyses were verified against the general Chi-Square test. A multivariable model was then performed to determine which of the bivariate results would remain independently associated with isolation using bivariate results that were significant at p < 0.10, after removing any necessary variable that were collinear or had missing data that decreased the sample size. All analytic assumptions were verified, and analyses were performed using SAS v9.449.

Qualitative Data

We used an inductive and deductive thematic analysis approach to analyze the data50. This involves identifying and comparing common emergent themes across transcripts and using pre-identified concepts from our research questions to organize and analyze the data. A 4-member analytical team that included the first author independently read 3 of the transcripts to gain a general understanding of the data and variations across participants. We generated a working set of codes that included a priori codes from the health equity implementation framework. Once we had a well-defined and established set of codes, two coders independently coded each transcript. Then, the team reviewed and finalized the coding to maintain consistency and consensus in our coding practice. We then collaboratively identified themes that emerged from data.

Mixed-Methods Data Integration

We used a convergent mixed-methods design to analyze the study, using both quantitative and qualitative data concurrently and iteratively to inform the results51, 52.

RESULTS

Phase 1 Results: Prevalence of Social Isolation and Patient Characteristics

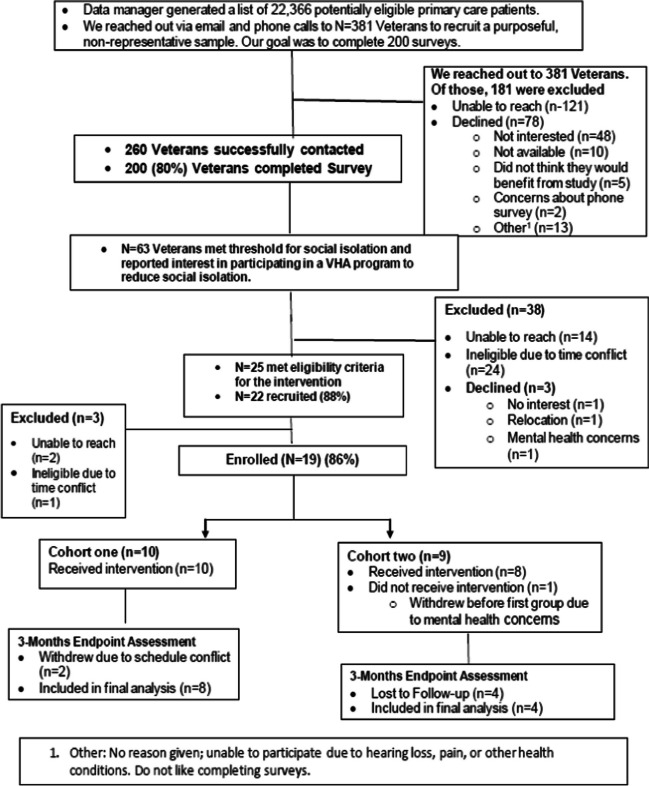

As shown in the CONSORT Figure, Phase 1 participants were recruited from 22,366 potentially eligible patients. We reached out to a non-representative sample of 381 veterans and successfully contacted 260. Of those, 200 completed the survey, resulting in a response rate of 80%. Survey results are presented in Table 1. Participants were mostly non-White (52%), male (73%), employed full-time (53%), married (60%), and 40% had at least some college education. Of the 200 patients surveyed, 39% met the threshold for social isolation. Among the isolated participants, their average LSNS-6 score was 8.2 (SD = 3.3, range 0–12). Participants who had children living with them (26.3% vs. 58%, p < 0.0001), identified as a caregiver (26% vs. 47%, p = 0.0088), were < 55 years old (40% vs. 58%, p = 0.0105), and reported any unmet social needs (14% vs. 26%, p = 0.03) were more likely to be socially isolated. Although not statistically significant, relative to White participants, more non-White participants were socially isolated (48% vs. 60%). Moreover, relative to non-isolated Veterans, isolated participants reported significantly worse physical (6.4 vs. 5.4; p = 0.001) and mental health (7.4 vs. 5.8; p < 0.0001). Both isolated (61%) and non-isolated (51%) participants expressed high levels of interest in participating in VA programs to reduce social isolation (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

CONNECTED Survey Results

| Overall (N = 200) Mean, (SD) |

Isolated NO (n = 123) Mean, (SD) |

Isolated YES (n = 77) Mean, (SD) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Isolation (LSNS-6 Score) | 14.9 (6.7); 0 – 30 | 19.1 (4.6); 13 – 30 | 8.2 (3.3); 0 – 12 | < 0.0001* |

| Sex | ||||

|

Male Female |

146 (73.0) 54 (27.0) |

91 (74.0) 32 (26.0) |

55 (71.4) 22 (28.6) |

0.6921 |

| Race | ||||

|

White Non-White |

95 (47.5) 105 (52.5) |

64 (52.0) 59 (48.0) |

31 (40.3) 46 (59.7) |

0.1047 |

| Ethnicity (Latino) | ||||

|

Yes No |

10 (5.0) 190 (95.0) |

3 (2.4) 120 (97.6) |

7 (9.1) 70 (90.9) |

0.0471* |

| Age | ||||

|

25–34 35–44 45–54 55–64 65–74 75–84 85 + |

26 (13.0) 28 (14.0) 40 (20.0) 46 (23.0) 46 (23.0) 13 (6.5) 1 (0.5) |

16 (13.0) 15 (12.2) 18 (14.6) 32 (26.0) 31 (25.2) 10 (8.1) 1 (0.8) |

10 (13.0) 13 (16.9) 22 (28.6) 14 (18.2) 15 (19.5) 3 (3.9) 0 (0) |

0.1580 |

| Age (comparing > 55 vs. 55 +) | ||||

|

18–54 55 + |

94 (47.0) 106 (53.0) |

49 (39.8) 74 (60.2) |

45 (58.4) 32 (41.6) |

0.0105* |

| Education | ||||

|

< HS-Trade Some-Associates Bachelor’s Master’s—PhD |

45 (22.5) 81 (40.5) 44 (22.0) 30 (15.0) |

30 (24.4) 51 (41.5) 27 (22.0) 15 (12.2) |

15 (19.5) 30 (39.0) 17 (22.1) 15 (19.5) |

0.1691 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||

|

Hetero/Straight Other |

195 (97.5) 5 (2.5) |

120 (97.6) 3 (2.4) |

75 (97.4) 2 (2.6) |

> 0.9999 |

| Relationship status | ||||

|

Married/partner Other |

121 (60.5) 79 (39.5) |

79 (64.2) 44 (35.8) |

42 (54.6) 35 (45.5) |

0.1729 |

| Employment status | ||||

|

Full time Part time Retired Unemployed In school On disability |

106 (53.0) 10 (5.0) 60 (30.0) 9 (4.5) 2 (1.0) 13 (6.5) |

64 (52.0) 6 (4.9) 41 (33.3) 3 (2.4) 1 (0.8) 8 (6.5) |

42 (54.6) 4 (5.2) 19 (24.7) 6 (7.8) 1 (1.3) 5 (6.5) |

0.4608 |

| Household income | ||||

|

Comfortable Just enough NOT enough |

124 (62.0) 62 (31.0) 14 (7.0) |

84 (68.3) 32 (26.0) 7 (5.7) |

40 (52.0) 30 (39.0) 7 (9.1) |

0.0621 |

| Lives alone | ||||

|

No Yes |

156 (78.0) 44 (22.0) |

99 (80.5) 24 (19.5) |

57 (74.0) 20 (26.0) |

0.2972 |

| Children live with you | ||||

|

No Yes |

97 (62.2) 59 (37.8) |

73 (73.7) 26 (26.3) |

24 (42.1) 33 (57.9) |

0.0001* |

| Caregiver | ||||

|

No Yes |

103 (66.0) 53 (34.0) |

73 (73.7) 26 (26.3) |

30 (52.6) 27 (47.4) |

0.0088* |

| Military Branch | ||||

|

Army Navy Marines Air Force National Guard Other |

112 (56.0) 24 (12.0) 22 (11.0) 39 (19.5) 2 (1.0) 1 (0.5) |

69 (56.1) 16 (13.0) 9 (7.3) 27 (22.0) 2 (1.6) 0 (0) |

43 (55.8) 8 (10.4) 13 (16.9) 12 (15.6) 0 (0) 1 (1.3) |

0.1485 |

| Era of Service | ||||

|

Vietnam Korean Gulf OEF/OIF/OND Other |

42 (21.0) 6 (3.0) 43 (21.5) 65 (32.5) 44 (22.0) |

31 (25.2) 3 (2.4) 23 (18.7) 40 (32.5) 26 (21.1) |

11 (14.3) 3 (3.9) 20 (26.0) 25 (32.5) 18 (23.4) |

0.3491 |

| Concerned about not feeling connected | ||||

|

Not concerned Somewhat concerned Very concerned |

127 (63.5) 49 (24.5) 24 (12.0) |

90 (73.2) 24 (19.5) 9 (7.3) |

37 (48.1) 25 (32.5) 15 (19.5) |

0.0010* |

| Interest (in VA program) | ||||

|

No Yes |

90 (45.0) 110 (55.0) |

60 (48.8) 63 (51.2) |

30 (39.0) 47 (61.0) |

0.1909 |

| Run out of food | ||||

|

No Yes |

187 (93.5) 13 (6.5) |

117 (95.1) 6 (4.9) |

70 (90.9) 7 (9.1) |

0.2531 |

| Worried about stable housing | ||||

|

No Yes |

184 (92.0) 16 (8.0) |

116 (94.3) 7 (5.7) |

68 (88.3) 9 (11.7) |

0.1794 |

| Lack of transport | ||||

|

No Yes |

184 (92.0) 16 (8.0) |

116 (94.3) 7 (5.7) |

68 (88.3) 9 (11.7) |

0.1794 |

| Food/Housing/Transport ANY | ||||

|

No Yes |

163 (81.5) 37 (18.5) |

106 (86.2) 17 (13.8) |

57 (74.0) 20 (26.0) |

0.0395* |

| Physical health (low scores → dissatisfied; high scores → satisfied); range 1–10 | 6.0 (2.1); 1 – 10 | 6.4 (1.9); 1 – 10 | 5.4 (2.2); 1 – 10 | 0.0010* |

| Mental health (low scores → dissatisfied; high scores → satisfied); range 1–10 | 6.8 (2.4); 1 – 10 | 7.4 (2.2); 1 – 10 | 5.8 (2.4); 1 – 10 | < 0.0001* |

Values are means (standard deviation); ranges for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables, with p-values from t-tests and Fisher’s Exact tests (due to the typical small cell counts; Mantel–Haenszel Chi-Square tests were used for ordinal/ranked data), respectively

Bold numbers with asterick indicate statistical significance

Figure 2.

CONNECTED CONSORT Diagram.

In Phase 1 we also identified 63 survey completers who were socially isolated and interested in participating in the intervention (Phase 2). Of those 63, 25 were successfully contacted and deemed eligible to participate in the intervention by providing informed consent for participation and being available for group meetings.

Phase 2 Results

Twenty-two participants were recruited from Phase 1 (88%); 19 enrolled (86%) in the intervention. The first ten 10 formed cohort 1 and the other 9 formed cohort 2. Two participants withdrew from the first cohort after the first session due to schedule conflicts, resulting in 80% retention. In the second cohort, one participant withdrew before the intervention began for mental health reasons, leaving 8. We retained 50% (4/8) of these participants. Retention in this cohort was lower because one of the peers left the study team halfway through the intervention. There were no changes made to the intervention following the peer’s departure. The peer’s participants were re-assigned to another peer, whom they had met. Some participants nonetheless disengaged in the study due to difficulties forming a relationship with the new peer.

Intervention Feasibility

Peers successfully delivered the intervention to study participants with fidelity, earning “satisfactory” for most fidelity elements and a total score of 18 out of 20 (90%). In terms of session adherence, 5 of 8 participants from cohort 1 completed at least 10 of the 12 group sessions. For cohort 2, as discussed above, we retained 4 (50%) of study participants due to a peer leaving the study. Of those 4 participants, 3 completed ≥ 10 group sessions.

Intervention Acceptability

Satisfaction rates with the intervention were 100% among intervention completers across both cohorts, and 85% of participants reported being “very satisfied” with CONNECTED. Qualitative interviews with 10 intervention completers (83%) corroborate these findings. Specifically, participants expressed satisfaction with the peer-facilitation component of the intervention, the telehealth modality, and the generalist approach, which emphasized inclusion of diverse patient groups across diagnostic categories. Two participants described their experiences with the program and how it benefited them as follows:

The very first group that I had I was so energized. …. I was so happy even though I did feel like, “maybe this isn’t for me.” ... And my husband could see it on my face…[group] just made me feel extremely happy… I really looked forward to every Wednesday, and every one-on-one phone call. -C06

COVID forced us into social isolation. And [CONNECTED] kind of does the opposite. It

forces you out of the social isolation so that you make a commitment to get out once a

week and …having interactions with other people…to start living outside the house again. And I like that you didn't have to just jump out with two feet. You had a platform to stand on to help you start engaging with people again. -C114

Participants described positive effects of the intervention beyond alleviating social isolation. They noted that the intervention improved their depressive and anxiety symptoms, helped them develop new skills, and enhanced their overall quality of life.

It’s good to see that the VA is really starting to look at ... so many different ways to deal with what veterans need, because we've just been through things that a lot of people don't experience. And giving those opportunities, and not just say, here, take this pill and go home. They're going to try to help you learn, grow, thrive, and become more, a better functioning person. -C04

[CONNECTED] definitely helped. I was becoming a little bit more reclusive…So, it's been good for me in that I've started to open back up and reaching back out to people…My wife has always been more social. But she started to become more reclusive with me, and now she's becoming more social again, too. -C26

I realized how I approached things and how I thought of certain people was the wrong way…which is basically self-isolating without realizing it. So, doing this program with all the other veterans in the group, [I realized] I need to break out of this. -C141

Preliminary Effects

Nineteen veterans participated in the CONNECTED intervention. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 2. Most were non-White (58%), male (53%), married (58%), did not live alone (79%), had at least an Associate’s degree (58%), were employed or full-time students (58%), had a mental health diagnosis (63%), and described their household income as being “comfortable” (63%).

Table 2.

CONNECTED Intervention Participants’ Characteristics (N = 19)

| Combined Cohorts (n = 19, %) | Cohort 1 (n = 10, %) | Cohort 2 (n = 9, %) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 25–34 | 3 (16%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (22%) |

| 35–44 | 4 (21%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (22%) |

| 45–54 | 8 (42%) | 4 (40%) | 4 (44%) |

| 55–64 | 2 (10%) | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

| 65–74 | 1 (5%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (11%) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10 (53%) | 6 (60%) | 4 (44%) |

| Female | 9 (47%) | 4 (40%) | 5 (55%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 6 (31%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (33%) |

| White | 8 (42%) | 4 (40%) | 4 (44%) |

| Asian | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1* (11%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (16%) | 2 (20%) | 1*(11%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single (never married) | 6 (31%) | 2 (20%) | 4 (44%) |

| Married | 11 (58%) | 7 (70%) | 4 (44%) |

| Divorced | 2 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (11%) |

| Education | |||

| High Diploma/ GED | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) |

| Some College | 7 (37%) | 4 (40%) | 3 (33%) |

| Associate Degree/ Trade certificate | 5 (26%) | 2 (20%) | 3 (33%) |

| ≤ Bachelor’s Degree | 6 (31%) | 4 (40%) | 2 (22%) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Full-time Employment/School | 11 (58%) | 8 (80%) | 3 (33%) |

| Employed part-time | 1 (5%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Unemployed | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) |

| Retired | 3 (16%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (22%) |

| Service Branch | |||

| Army | 13 (68%) | 7 (70%) | 6 (67%) |

| Marines | 3 (16%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (11%) |

| Air Force | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) |

| Navy | 1 (5%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Service Era | |||

| Gulf war | 8 (42%) | 5 (50%) | 3 (33%) |

| OEF/OIF/OND | 8 (42%) | 4 (40%) | 4 (44%) |

| Vietnam War | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (11%) |

| Korean War | 1 (5%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| None | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Income | |||

| Comfortable | 12 (63%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (67%) |

|

Do not have enough to make ends meet |

2 (10%) | 1 (10%) | 1 (11%) |

| Have just enough to make ends meet | 5 (26%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (22%) |

| Living Arrangement | |||

| Lives alone | 4 (21%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (22%) |

| Does not live alone | 15 (78%) | 8 (80%) | 7 (78%) |

| Mental Health Diagnoses* | |||

|

Personality disorders Mood disorders Severe Mental Illness Substance use disorders (SUD) PTSD No diagnosis |

1 (5%) 7 (37%) 3 (16%) 3 (16%) 5 (26%) 7 (37%) |

0 (0%) 4 (40%) 2 (20%) 1(10%) 3 (30%) 4(40%) |

1 (11%) 3 (33%) 1 (11%) 2 (22%) 2 (22%) 3 (33%) |

% refers to percentage of participants in each cohort

*Diagnoses were included if they were in a mental health visit note completed within a year prior to the end of study participation. Some participants had multiple diagnoses therefore the total percentage will be greater than 100

In Table 3, we show the combined (cohorts 1 and 2) results on study outcome measures. Overall, the intervention led to statistically significant improvements in social isolation as indicated by the change in scores from baseline to 3 months (+ 5.91, SD = 4.99; p = 0.002). There was also statistically significant improvement in scores for social support (+ 0.74, SD = 1.09; p = 0.03), anxiety (-3.92, SD = 3.73; p = 0.003), and depression (-3.83, SD = 3.13); p = 0.001). Although not statistically significant, participants also improved on life engagement, loneliness, and mental health functioning. There was no improvement in perceived physical health functioning. We summarize the study results in Fig. 3 below.

Table 3.

Effects of CONNECDTED on Study Outcomes (Combined Cohort Results n = 12)

| Baseline (pre-intervention) Mean, (SD) |

Post-Intervention Mean, (SD) |

Change in scores from baseline to post-intervention Mean, (SD) |

p-value (for non-zero change) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Social Isolation LSNS-6 |

6.95 (3.41) | 13.36 (5.95) | 5.91 (4.99) | 0.0028 |

|

Social Support MSPSS |

4.33 (1.01) | 5.23 (0.94) | 0.74 (1.09) | 0.0385 |

|

Anxiety GAD-7 |

10.00 (5.06) | 4.67 (0.23) | -3.92 (3.73) | 0.0039 |

|

Depression PHQ-9 |

11.68 (6.61) | 5.50 (6.36) | -3.83 (3.13) | 0.0014 |

|

Life Engagement LET |

21.16 (5.04) | 24.83 (6.19) | 2.17 (3.51) | 0.0559 |

|

Loneliness ULS-6 |

16.26 (4.34) | 13.58 (4.91) | -1.92 (3.45) | 0.0805 |

|

Physical functioning VR-12(physical) |

37.79 (8.33) | 43.41 (11.36) | 0.95 (5.55) | 0.7549 |

|

Mental Health functioning VR-12 (mental) |

37.14 (7.35) | 31.90 (8.81) | -1.70 (4.67) | 0.5189 |

Values are means (standard deviations) for baseline and post-intervention and means (95% confidence intervals) for change, with p-values from one-sample t-tests for H0 = 0

Bold numbers with asterick indicate statistical significance

Figure 3.

Summary of CONNECTED pilot feasibility study results.

DISCUSSION

Despite its substantial negative health outcomes 2–4, 10, effective interventions to reduce social isolation, especially among diverse patient populations, remain scarce 53. In this study, we assessed the feasibility and acceptability of CONNECTED, a novel social isolation intervention for diverse patients in primary care settings. We also explored preliminary effectiveness of the intervention to inform the design of a future effectiveness trial.

Overall, results demonstrate that CONNECTED is feasible and acceptable. Findings indicate that 39% of survey participants were socially isolated, which is consistent with prior literature demonstrating high rates of social isolation and loneliness in veteran populations24, 25. Notably, results show high rates of social isolation in veterans under the age of 55. This finding adds to growing reports of social isolation in young adulthood54, 55. It also points to the need to assess and mitigate social isolation in this subgroup of patients who may be overlooked for services due to their age, given that most social isolation and loneliness interventions tend to focus on older adults27, 53, 56. Younger adults may experience life changes such as relocation and care giving for young children or older adults that put them at greater risk of social isolation and negative health sequelae. Emerging studies also suggest that social isolation may be more detrimental for young adults compared to older adults54, 55,57, which reinforces the need to intervene on social isolation in this age group.

Consistent with prior studies 58–60, findings indicate that social isolation was more prevalent among those who reported any unmet social needs relative to those who did not. This is important because social isolation, as a negative social determinant of health, may exacerbate the effects of other negative social risk factors, such as food and housing insecurity, to impact population health. Our findings also extend prior literature by demonstrating that veterans desire assistance with social isolation.

To begin to address the lack of diversity in social isolation interventions, we piloted CONNECTED in a diverse sample of primary care veterans across age groups, socioeconomic status, sex, and diagnostic categories. Our findings suggest that CONNECTED is feasible in diverse patient populations with complex health and social needs. This is a major strength of the intervention, and if effective, CONNECTED could fill a major gap in patient care, given that most existing social isolation interventions have been tested primarily among participants who are female, White, and older 27.

Acceptability of the intervention was high. All participants perceived the intervention to be effective and beneficial. Specifically, they identified the peer interventionists, telehealth modality, and inclusion of patients across diagnostic categories as helpful. Building on prior literature, which has shown that many social isolation interventions have had weak effects due to their narrow focus9, 27, 31, we designed CONNECTED to target multiple dimensions of social isolation based on Wang and colleagues’ conceptual model 37 and to incorporate multiple strategies to increase social connectedness. These include creating opportunities for social engagement, individualized navigation services, skill building, psychoeducation, and peer support. Results also indicate that this intense approach is acceptable to participants and provides a comprehensive method to improve social connectedness.

Although not powered to detect significant change, CONNECTED produced statistically significant improvement in social isolation scores from baseline to 3 months. Participants also had significantly improved scores for depression, anxiety, and perceived social support. Results on other measures improved but were not statistically significant. These findings suggest that CONNECTED has the potential to be an effective tool to address social isolation.

This study included a diverse, although a small, non-representative sample of veterans from one Medical Center. Replication and expansion of the survey with a larger veteran population are needed to produce generalizable findings. Similarly, future testing of CONNECTED, with some modifications to increase study retention, such as better peer coverage, in a fully-powered, randomized controlled trial is needed to evaluate effectiveness and readiness for implementation in VA settings.

In summary, this pilot study demonstrates that CONNECTED is a feasible and acceptable social isolation reduction intervention. CONNECTED is designed to be delivered by VHA peers, which may facilitate future implementation given that peers constitute a growing, yet affordable, workforce, compared to licensed clinicians. Use of peers as interventionists also contributes to the acceptability of interventions because, as veterans themselves, peers are relatable to VHA patients and are well-suited to address issues associated with social isolation, such as stigma38,61,62. Moreover, the telehealth modality may contribute to increased reach of the intervention by eliminating transportation barriers. The combined individual and group format provides another model for social isolation interventions and should be tested more broadly to determine whether various levels of intervention intensity provide greater and sustained benefits.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author’s Contributions:

We would like to thank the study participants, and Mr. James Miller who contributed to the study as a volunteer peer. We are thankful for our clinical and community partners who facilitated the delivery of CONNECTED, and the research staff members, Emily Austin and Denise S. Zou, for their contributions to the study.

Funding

This study was funded by VA HSR&D SWIFT award and a VA HSR&D Career Development Award -2 16–153 to Dr. Eliacin. It also received support from the Regenstrief Institute, Inc.

Data Availability:

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations:

Conflict of Interest:

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

None.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci: A journal for the Association for Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):227–237. doi: 10.1177/1745691614568352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt-Lunstad J. Social isolation and health. Heath Affairs/Robert Wood Johnson. June 22, 2020. Accessed 9/11/2023 at: Social Isolation And Health | Health Affairs.

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J. The major health implications of social connection. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2021;30(3):251–259. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt-Lunstad J, Steptoe A. Social isolation: An underappreciated determinant of physical health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2022;43:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt-Lunstad J. Social connection as a public health issue: The evidence and a systemic framework for prioritizing the "social" in social determinants of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052020-110732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157–171. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Veazie S, Gilbert J, Winchell K, Paynter R, Guise JM. Addressing social isolation to improve the health of older adults: A rapid review. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2019 Feb. Report No.: 19-EHC009-EF. AHRQ Rapid Evidence Product Reports. [PubMed]

- 8.DeJulio B, Hamel L, Munana C, Brodie M. Loneliness and social isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An international survey. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2018. Accessed 9/11/2023: https://www.kff.org/other/report/loneliness-and-social-isolation-in-the-united-states-the-united-kingdom-and-japan-an-international-survey/.

- 9.Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(2):147–157. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holt-Lunstad J. A pandemic of social isolation? World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):55–56. doi: 10.1002/wps.20839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piette J, Solway E, Singer D, Kirch M, Kullgren J, Malani P. Loneliness among older adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. University of Michigan National Poll on Healthy Aging; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith BJ, Lim MH. How the COVID-19 pandemic is focusing attention on loneliness and social isolation. Public Health Res Pract. 2020;30(2):3022008. doi: 10.17061/phrp3022008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50(1):31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerst-Emerson K, Jayawardhana J. Loneliness as a public health issue: The impact of loneliness on health care utilization among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):1013–1019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377–385. doi: 10.1037/a0022826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzman JS, Sohn L, Harada ND. Living alone and outpatient care use by older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(4):617–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuwert P, Knaevelsrud C, Pietrzak RH. Loneliness among older veterans in the United States: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for homelessness among US veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:177–195. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.PTSD: National Center for PTSD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. How common is PTSD in veterans. Accessed 9/11/2023: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp. Published 2020.

- 20.Teo AR, Marsh HE, Forsberg CW, et al. Loneliness is closely associated with depression outcomes and suicidal ideation among military veterans in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2018;1(230):42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grenawalt TA, Lu J, Hamner K, Gill C, Umucu E. Social isolation and well-being in veterans with mental illness. J Ment Health. 2023;32(2):407–411. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.2022625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mistry R, Rosansky J, McGuire J, McDermott C, Jarvik L, UPBEAT Collaborative Group. Social isolation predicts re-hospitalization in a group of older American veterans enrolled in the UPBEAT program. Unified Psychogeriatric Biopsychosocial Evaluation and Treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(10):950–959. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Teo AR, Markwardt S, Hinton L. Using Skype to beat the blues: Longitudinal data from a national representative sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(3):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suntai Z, White B. Social isolation among older veterans: Findings from the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Aging Ment Health. 2022;26(7):1345–1352. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1942434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westat, Annual Warrior Survey. Report of Findings. 2019, Prepared by Westat. Accessed 9/11/2023. 2019-annual-warrior-survey.pdf (woundedwarriorproject.org)

- 26.Annual Warrior Survey. Executive Summary. 2022. Accessed 9/11/2023. wwp-2022-annual-warrior-survey-executive-summary.pdf (woundedwarriorproject.org)

- 27.O'Rourke HM, Collins L, Sidani S. Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):214. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0897-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotterell N, Buffel T, Phillipson C. Preventing social isolation in older people. Maturitas. 2018;113:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(3):799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tung EL, De Marchis EH, Gottlieb LM, Lindau ST, Pantel MS. Patient experiences with screening and assistance for social isolation in primary caresSettings. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(7):1951–1957. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):129. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eldridge SM, Chan CL, Campbell MJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2:64. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, et al. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):503–513. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang Y, Powers DA, Park NS, Chiriboga DA, Chi I, Lubben J. Performance of an Abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) in Three Ethnic Groups of Older Asian Americans. Gerontologist. 2022;62(2):e73–e81. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grace SL, Tan Y, Cribbie RA, Nguyen H, Ritvo P, Irvine J. The mental health status of ethnocultural minorities in Ontario and their mental health care. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;26(16):47. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0759-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siette J, Pomare C, Dodds L, Jorgensen M, Harrigan N, Georgiou A. A comprehensive overview of social network measures for older adults: A systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2021;Nov-Dec;97:104525. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2021.104525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D, et al. Social isolation in mental health: A conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(12):1451–1461. doi: 10.1007/s00127-017-1446-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shalaby RAH, Agyapong VIO. Peer support in mental health: Literature review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(6):e15572. doi: 10.2196/15572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valaitis RK, Carter N, Lam A, Nicholl J, Feather J, Cleghorn L. Implementation and maintenance of patient navigation programs linking primary care with community-based health and social services: A scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):116. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Development of a theory-informed questionnaire to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):279. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07577-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of health care interventions: A theoretical framework and proposed research agenda. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(3):519–531. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woodward EN, Matthieu MM, Uchendu US, Rogal S, Kirchner JE. The health equity implementation framework: Proposal and preliminary study of hepatitis C virus treatment. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0861-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirschtritt ME, Kroenke K. Screening for depression. JAMA. 2017;18(8):745–746. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cecil H, Stanley MA, Carrion PG, Swann A. Psychometric properties of the MSPSS and NOS in psychiatric outpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(5):593–602. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199509)51:5<593::aid-jclp2270510503>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scheier MF, Wrosch C, Baum A, et al. The Life Engagement Test: Assessing purpose in life. J Behav Med. 2006;29(3):291–298. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kazis LE, Rogers WH, Rothendler J, et al. Outcome performance measure development for persons with multiple chronic conditions. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 49.SAS Institute Inc . Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide. 5. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles: Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Palinkas LA and Cooper BR. Mixed methods evaluation in dissemination and implementation science. In: Brownson RC, Colditz G, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice. New York 2017, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 53.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2020 Feb 27. [PubMed]

- 54.Beam CR, Kim AJ. Psychological sequelae of social isolation and loneliness might be a larger problem in young adults than older adults. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S58–S60. doi: 10.1037/tra0000774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Primack BA, Shensa A, Sidani JE, et al. Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the U.S. Am. J Prev Med. 2017;53(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Glob Health Res Policy. 2020;5:27. doi: 10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammig O. Health risks associated with social isolation in general and in young, middle and old age. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Algren MH, Ekholm O, Nielsen L, Ersboll AK, Bak CK, Andersen PT. Social isolation, loneliness, socioeconomic status, and health-risk behaviour in deprived neighbourhoods in Denmark: A cross-sectional study. SSM Popul Health. 2020;10:100546. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal G, Pirrie M, Gao A, Angeles R, Marzanek F. Subjective social isolation or loneliness in older adults residing in social housing in Ontario: A cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(3):E915–E925. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adepoju OE, Chae M, Woodward L, et al. Correlates of social isolation among community-dwelling older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9:702965. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.702965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chinman M, Daniels K, Smith J, et al. Provision of peer specialist services in VA patient aligned care teams: Protocol for testing a cluster randomized implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0587-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosland AM, Wong E, Maciejewski M, et al. Patient-centered medical home implementation and improved chronic disease quality: A longitudinal observational study. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2503–2522. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during this study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.