Most cancer found in the mouth is oral squamous cell carcinoma. This disease is uncommon in the developed world, except in parts of France, but it is common in the developing world, particularly Southeast Asia and Brazil. Oral cancer typically is seen in men past middle age (although it is increasingly common in younger people), tobacco users, and members of lower socioeconomic groups.

Table 1.

| Oral malignant neoplasms |

|---|

| Common |

|

| Uncommon |

|

Etiologic factors (acting on a genetically susceptible individual) include tobacco use (75% of people with oral cancer smoke), betel use (betel leaf, and often tobacco, plus spices, slaked lime [calcium hydroxide], and areca [betel] nut), alcohol consumption, a diet poor in fresh fruit and vegetables, infective agents (Candida, viruses), immune deficiency, and, in the case of lip carcinoma, exposure to sunlight.

Additional primary neoplasms may arise in the aerodigestive tract. These lesions occur in up to 25% of people who have had oral cancer for longer than 3 years and in up to 40% of persons who continue to smoke. Similarly, patients with lung cancer are at risk of developing second primary oral cancers.

Potentially malignant lesions or conditions may include some erythroplasias, dysplastic leukoplakias (about one half of oral carcinomas have associated leukoplakia), lichen planus, submucous fibrosis, and chronic immunosuppression. Rare causes of oral cancer include tertiary syphilis, discoid lupus erythematosus, dyskeratosis congenita, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome (iron deficiency and dysphagia).

DIAGNOSIS

Too many patients with oral cancer seek evaluation late in the course of their disease or their disease is detected when disease it is advanced and metastasis to lymph nodes has occurred. With earlier detection, treatment is less complicated, the cosmetic and functional results are better, and survival is improved.

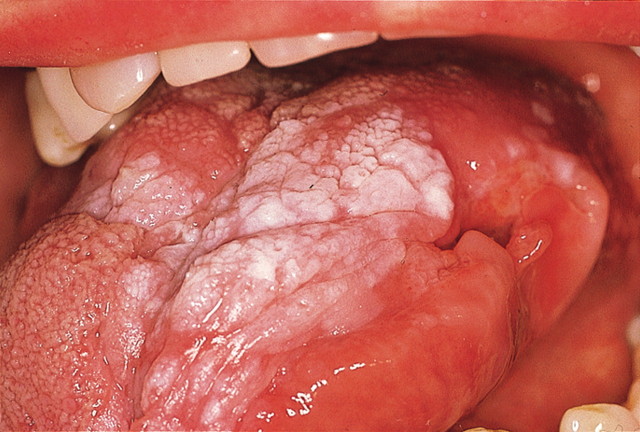

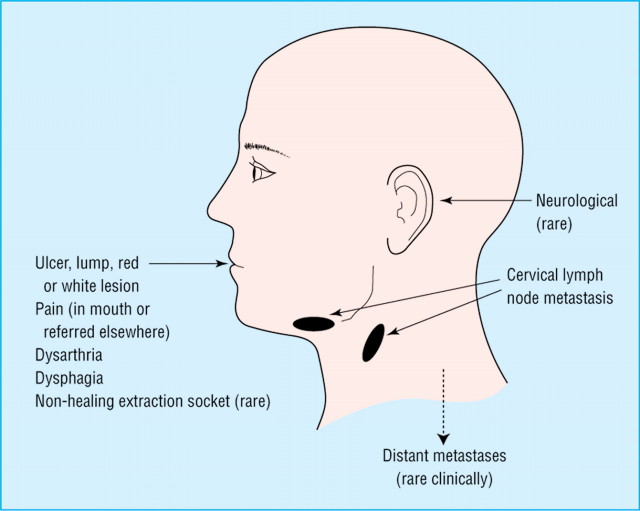

Carcinomas arise anywhere in the oral cavity, often on the posterolateral margin of the tongue and floor of the mouth—the “coffin” or “graveyard” area. It is crucial, therefore, to examine the entire oral cavity both visually and manually and to inspect and palpate the posterolateral margins of the tongue and the floor of the mouth. Possible findings include a solitary chronic ulceration (figure 1), red or white lesion (figure 2), indurated lump (figure 3), fissure, or enlarged cervical lymph node. Lip carcinoma manifests as thickening, crusting, or ulceration, usually of the lower lip (figure 4).

Figure 1.

Carcinoma of the tongue presenting as an ulcer

Figure 2.

Carcinoma of the tongue with associated white lesions

Figure 3.

Carcinoma of the tongue manifests as a lump

Figure 4.

Carcinoma of the lip

Enlargement of an anterior cervical lymph node may be detected during palpation (figure 5). Some 30% of patients present with palpably enlarged nodes containing metastases; of those who do not, an additional 25% will develop nodal metastases within 2 years. Molecular techniques can reveal the presence of tumor tissue in many histologically normal nodes.

Figure 5.

Possible features of oral carcinoma

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion of a solitary lesion present for longer than 3 weeks, particularly if it is indurated, accompanied by cervical lymphadenopathy, or found in a patient who is in a high-risk group.

Investigations

It is essential to confirm the diagnosis and to determine whether cervical lymph nodes are involved or the patient has other primary tumors or metastases. Therefore, the following are usually indicated:

Lesional biopsy (usually an incisional biopsy, but an oral brush biopsy is now available, mainly for patients with wide-spread, potentially malignant lesions and for revealing malignancy in lesions that appear benign)

Jaw and chest radiography

Endoscopy

Complete blood cell count and liver function tests

Computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging can determine the extent and invasion of the tumor and if any of the cervical lymph nodes are involved. Ultrasound-guided cytologic analysis of nodes may be useful. The staging systems of tumor, nodes, metastases (TNM) classification and T and N integer score (TANIS) are often used. Molecular analysis techniques are being introduced for prognostication in potentially malignant lesions and tumors, as well as to identify nodal metastases.

MANAGEMENT

The prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma is site dependent. For intraoral carcinoma, 5-year survival may be as low as 30% for posterior lesions that often are detected late in the course of the disease. For lip carcinoma, however, 5-year survival is often greater than 70%. Important factors to consider in management are quality of life and patient education: in one study, 47% of patients still smoked and 36% drank alcohol to excess at least 6 months after the diagnosis of oral cancer. Only a third were aware that these habits were important in the development of oral cancer.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is now treated surgically or with irradiation, although few unequivocal controlled trials of treatment methods have been conducted. Photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy have occasional applications. Clinics staffed by both surgeons and oncologists, and their support staff, usually have a consistent treatment policy and offer the best outcomes.

SURGERY

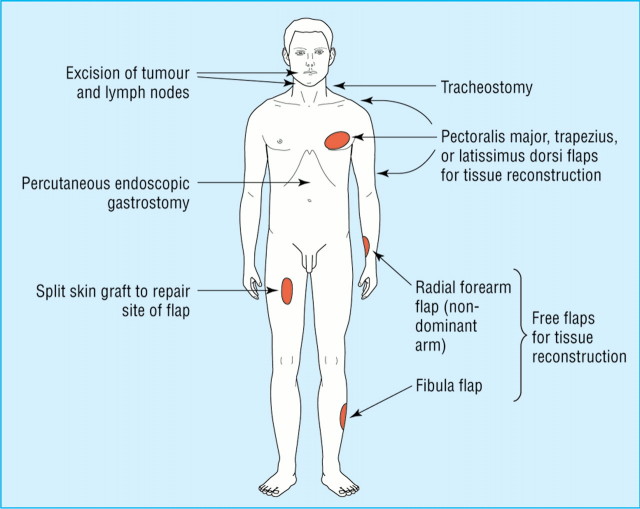

Surgical intervention allows the complete excision of a tumor and lymph nodes, followed by a full histologic examination for staging, which has implications for prognostication and assessing the need for adjuvant radiotherapy (figure 6). Surgery can also be used for radioresistant tumors. Disadvantages are mainly the perioperative mortality and morbidity, but modern techniques have significantly decreased these adverse outcomes as well as decreased the aesthetic and functional defects that result from surgery.

Figure 6.

Surgical procedures that may be used in treating patient with oral cancer

Patients who succumb to oral cancer usually die because of failure to control the primary malignancy or because of nodal metastases. Death because of distant metastasis is unusual. Ablative surgery excises the cancer with, ideally, at least a 2-cm margin of clinically normal tissue. If a node has clinical signs of invasion, it is reasonable to assume that other nodes may also be involved, and they must be removed by traditional radical neck dissection. “Functional” neck dissections, modified to preserve the jugular, sternomastoid, or accessory nerve while ensuring complete removal of involved nodes, have gained popularity. Moderate-dose radiotherapy is sometimes used to “sterilize” cervical nodes affected by metastatic disease.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction is tailored to the patient's ability to cope with a long operation and the risk of substantial morbidity.

Soft-tissue reconstruction

Local flaps (such as nasolabial flaps) provide thin, reliable flaps suitable for repairing small defects. Often, however, tissue must be brought into the region to repair large defects. For these larger areas, split skin grafts or flaps—free or pedicle—are required.

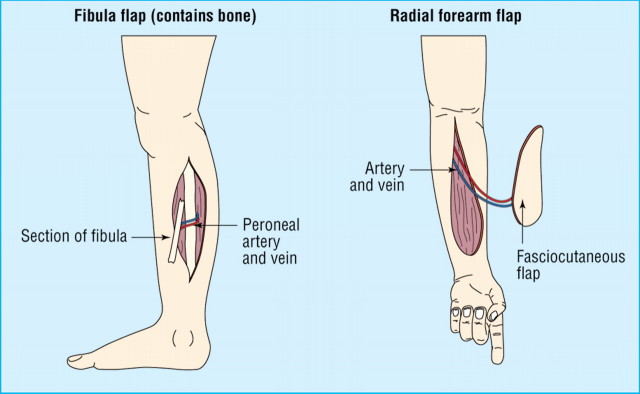

Free flaps. Microvascular surgery facilitates excellent tissue reconstruction in a single operation by using free flaps. For example, forearm flaps based on radial vessels are particularly useful when replacing soft tissue. Flaps based on the fibula may be used if bone is also required (figure 7).

Figure 7.

Free flaps that may be used for tissue reconstruction after tumor resection

Pedicle flaps. Myocutaneous or osteomyocutaneous flaps are based on a feeding vessel to muscle and perforators to the skin paddle. These flaps may be used in a 1-stage operation to replace skin, and because they also contain muscle, they have adequate bulk to help repair defects. Pedicle flaps may also be used to import bone (usually rib). Examples include flaps based on the pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, or trapezius muscles. Flaps from the forehead or deltopectoral pedicle were once the mainstay for reconstruction, but they required a 2-stage operation, replaced only skin, and relied on a tenuous blood supply.

Hard-tissue reconstruction

Ideally, hard-tissue reconstruction is performed at the time of tumor resection. Dental implants can then be inserted to accommodate a dental prosthesis. Bone is traditionally in the form of free nonvascularized bone grafts taken from the iliac crest or a rib, but these grafts may survive poorly if contaminated or the vascularity is impaired after irradiation. In such cases, or when the defect is large, an osteomyocutaneous flap improves the graft's vascular bed. True free vascularized bone grafts such as fibula grafts have great benefits, but they are time-consuming to perform and require considerable expertise.

The benefits of bone grafting for maxillary defects are less certain, and maxillary reconstruction is usually accomplished with an obturator (bung), which has the advantage that the cavity can subsequently be inspected.

Surgical complications in patients with oral cancer may include infection, carotid artery rupture, salivary fistulae, and thoracic duct leakage (chylorrhea).

RADIOTHERAPY

With radiotherapy, normal anatomy and function are maintained, general anesthesia is not needed, and salvage surgery is still available if radiotherapy fails. Radiotherapy has its disadvantages: adverse effects are common, and subsequent surgery is more difficult and hazardous (with survival rates further reduced).

Table 2.

| Causes of a complaint of dry mouth |

|---|

| latrogenic |

|

| Salivary gland disease |

|

| Dehydration |

|

| Psychogenic |

Methods of delivery

Radiotherapy can be delivered by external beams or by implanting a radioisotope. External beam irradiation (teletherapy) is commonly accompanied by side effects (see subsequent discussion). With interstitial therapy (brachiotherapy, plesiotherapy), implants of iridium-192 give a radiation dose equivalent to teletherapy but confined to the lesion and immediate area. Plesiotherapy thus causes fewer complications but is used mainly for tumors less than 2 cm in diameter and in selected sites.

Complications

Immediate complications include painful mucositis (figure 8). The time to healing depends on the radiation dose but is usually complete within 3 weeks of the end of treatment. Tobacco smoking delays resolution, and mucositis can provide a portal for systemic infection. Mucositis can be reduced by minimizing doses of radiation or cytotoxic drugs, avoiding irritants (smoking, spirits, and spicy foods), maintaining good oral hygiene, cooling the mouth with ice, and using certain therapeutic agents (topical aspirin, benzydamine, lidocaine, chlorhexidine, sucralfate, or polymyxin E and tobramycin sulfate).

Figure 8.

Radiation-induced mucositis

Osteoradionecrosis is a potentially serious complication (figure 9). With its high density and poor vascularity, the mandible is more prone to develop this complication than is the maxilla. Risk of osteoradionecrosis increases with higher radiation dose, larger radiation fraction size and number, and extraction of teeth after radiotherapy.

Figure 9.

Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible

Complications of radiotherapy in children include enamel hypoplasia, microdontia, impaired tooth development and eruption, and alterations to the developing craniofacial skeleton.

Dry mouth (xerostomia) may cause a subjective complaint of dry mouth, difficulty with speech and swallowing dry foods, a burning sensation in the mouth, dental caries, oral candidiasis, and bacterial sialadenitis. Gustatory (sugar-free chewing gum) or pharmacologic (cholinergic agents) stimuli may increase the functional activity of residual salivary tissue. Pilocarpine in doses of up to 5 mg 3 times daily can be effective. Patients with a dry mouth should avoid anything that further impairs salivation, such as drugs, tobacco, and alcohol. They may benefit from dietary control, taking frequent sips of water (particularly during eating), and using artificial saliva (such as Oralbalance) and topical fluorides.

Other complications of radiotherapy include loss of taste and cervical atherosclerosis.

Further reading

Allison PJ, Locker D, Feine JS. Therelationship between dental status and health-related quality of lifein upper aerodigestive tract cancer patients. OralOncol 1999;35:138-143.

Cancer Rescarch Campaign. Factsheet14.1. London: CRC; 1993.

Prince S, Bailey BM. Squamous carcinoma ofthe tongue: review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999;37:164-174.

Rodrigues VC, Moss SM, Tuomainen H. Oralcancer in the UK: to screen or not to screen. OralOncol 1998;34:454-465.

Rogers SN, Hannah L, Lowe D, MagennisP. Quality of life 5-10 years after primary surgery for oral andoro-pharyngeal cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 1999;27:187-191.

Schepman K, der Meij E, Smeele L, der WaalI. Concomitant leukoplakia in patients with oral squamous cellcarcinoma. Oral Dis 1999;5:206-209.

Sciubba JJ. Improving detection ofprecancerous and cancerous oral lesions. Computer-assisted analysisof the oral brush biopsy. US Collaborative Oral-Dx StudyGroup. J Am Dent Assoc 1999;130:1445-1457.

Scully C, Ward-Booth P. Detection andtreatment of early cancers of the oral cavity. Crit Rev OncolHaematol 1995;21:63-75.

Summary points

Oral cancer may present as a solitary lump, ulcer, or red or white lesion

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is mainly a disease of men over middle age, but its prevalence is increasing in other age groups

Earlier diagnosis offers better treatment, cosmetic and functional outcome, and survival

Any oral lesion persisting more than 3 weeks should be treated with suspicion; biopsy is mandatory

Biopsy is also mandatory to confirm diagnosis and determine the extent of involvement and presence of any second primary neoplasms

Dental treatment, both preventive and curative, is essential before radiotherapy to minimize oral disease and the possible adverse consequences of operative intervention

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the advice of Rosemary Toy, general practitioner, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire, England, and David Cunliffe, senior registrar in maxillofacial surgery, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, England.

Competing interests: None declared

This article was published in BMJ 2000;321:97-100.

This article is the third in a series adapted from The ABC of Oral Health, edited by Crispian Scully and published by the BMJ Publishing Group in November 2000.

Authors: Crispian Scully is dean and Stephen Porter is professor of oral medicine at the Eastman Dental Institute for Oral Health Care Sciences, University College London, University of London (www.eastman.ucl.ac.uk).