Abstract

Background

Endoscopic therapy reduces the rebleeding rate and the need for surgery in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers.

Objectives

To determine whether a second procedure improves haemostatic efficacy or patient outcomes or both after epinephrine injection in adults with high‐risk bleeding ulcers.

Search methods

For our update in 2014, we searched the following versions of these databases, limited from June 2009 to May 2014: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to May Week 2 2014; Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily Update May 22, 2014; Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations May 22, 2014 (Appendix 1); Evidence‐Based Medicine (EBM) Reviews—the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) April 2014 (Appendix 2); and EMBASE 1980 to Week 20 2014 (Appendix 3).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing epinephrine alone versus epinephrine plus a second method. Populations consisted of patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers, that is, patients with haemorrhage from peptic ulcer disease (gastric or duodenal) with major stigmata of bleeding as defined by Forrest classification Ia (spurting haemorrhage), Ib (oozing haemorrhage), IIa (non‐bleeding visible vessel) and IIb (adherent clot) (Forrest Ia‐Ib‐IIa‐IIb).

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures as expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. Meta‐analysis was undertaken using a random‐effects model; risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for dichotomous data.

Main results

Nineteen studies of 2033 initially randomly assigned participants were included, of which 11 used a second injected agent, five used a mechanical method (haemoclips) and three employed thermal methods.

The risk of further bleeding after initial haemostasis was lower in the combination therapy groups than in the epinephrine alone group, regardless of which second procedure was applied (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.81). Adding any second procedure significantly reduced the overall bleeding rate (persistent and recurrent bleeding) (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.76) and the need for emergency surgery (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.93). Mortality rates were not significantly different when either method was applied.

Rebleeding in the 10 studies that scheduled a reendoscopy showed no difference between epinephrine and combined therapy; without second‐look endoscopy, a statistically significant difference was observed between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, with fewer participants rebleeding in the combined therapy group (nine studies) (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.48).

For ulcers of the Forrest Ia or Ib type (oozing or spurting), the addition of a second therapy significantly reduced the rebleeding rate (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.88); this difference was not seen for type IIa (visible vessel) or type IIb (adherent clot) ulcers. Few procedure‐related adverse effects were reported, and this finding was not statistically significantly different between groups. Few adverse events occurred, and no statistically significant difference was noted between groups.

The addition of a second injected method reduced recurrent and persistent rebleeding rates and surgery rates in the combination therapy group, but these findings were not statistically significantly different. Significantly fewer participants died in the combined therapy group (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.00).

Epinephrine and a second mechanical method decreased recurrent and persistent bleeding (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.54) and the need for emergency surgery (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.62) but did not affect mortality rates.

Epinephrine plus thermal methods decreased the rebleeding rate (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.78) and the surgery rate (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.62) but did not affect the mortality rate.

Our risk of bias estimates show that risk of bias was low, as, although the type of study did not allow a double‐blind trial, rebleeding, surgery and mortality were not dependent on subjective observation. Although some studies had limitations in their design or implementation, most were clear about important quality criteria, including randomisation and allocation concealment, sequence generation and blinding.

Authors' conclusions

Additional endoscopic treatment after epinephrine injection reduces further bleeding and the need for surgery in patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcer. The main adverse events include risk of perforation and gastric wall necrosis, the rates of which were low in our included studies and favoured neither epinephrine therapy nor combination therapy. The main conclusion is that combined therapy seems to work better than epinephrine alone. However, we cannot conclude that a particular form of treatment is equal or superior to another.

Plain language summary

Epinephrine injection versus epinephrine injection and a second endoscopic method in high‐risk bleeding ulcers

Background

Peptic ulcers develop when the usual protective mechanism of the body breaks down and digestive juices produced in the stomach, intestines and digestive glands damage the lining of the stomach or duodenum. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori are common causes of ulcers.

When ulcers in the stomach and small intestine (duodenum) start to bleed extensively (haemorrhage), the bleeding can be life threatening and requires emergency treatment.

Patients undergo an endoscopy so clinicians can locate the source of bleeding. Active bleeding or non‐bleeding visible blood vessels at endoscopy are deemed 'high risk,' in that further bleeding may occur even if the initial haemorrhage can be stopped. Once the source of bleeding has been identified, endoscopic therapy reduces rebleeding rate, need for surgery and deaths. Endoscopic therapy consists of an agent to stop the bleeding, which is injected into the bleeding area; epinephrine (adrenaline) is the most popular agent. Experts disagree on the need for a second procedure such as bipolar electrocoagulation, heater probe, sclerosant or clips immediately after epinephrine; although it seems to reduce further bleeding, the effects of a second procedure on continuing illness (morbidity), surgery rates and death remain unclear.

Review question

In bleeding peptic ulcers, does a second endoscopic method reduce further bleeding, the need for emergency surgery and death rates?

Study characteristics

We performed an extensive search for randomised trials comparing epinephrine alone versus epinephrine plus a second method. We found 19 clinical trials involving 2033 randomly assigned participants

Key results

We found that adding a second procedure reduced the further bleeding rate and the need for emergency surgery, but the effect of this approach on death rates has not been proven. In conclusion, additional endoscopic treatment after epinephrine injection reduces further bleeding and the need for surgery in patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcer.

Quality of the evidence

Our risk of bias estimates show that the overall quality of the included studies was moderate or high. Although some studies had limitations in their design or implementation, most were clear about important quality criteria including randomisation and allocation concealment, sequence generation and blinding. We rated the quality of evidence as moderate for most outcomes. Further research is likely to have an impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the conclusions of this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method in high‐risk bleeding ulcers.

| Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method in high‐risk bleeding ulcers | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with high‐risk bleeding ulcers Settings: secondary care (hospital) Intervention: epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method | |||||

| Recurrent and persistent bleeding overall rates with or without second‐look endoscopy Rebleeding (persistent or recurrent bleeding) | Study population | RR 0.57 (0.43‐0.76) | 1926 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderatea | Favours combined therapy | |

| 223 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (96‐170) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 222 per 1000 | 127 per 1000 (95‐169) | |||||

| Surgery rate Number requiring emergency surgery | Study population | RR 0.68 (0.5‐0.93) | 1841 (18 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | Favours combined therapy | |

| 106 per 1000 | 72 per 1000 (53‐99) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 102 per 1000 | 69 per 1000 (51‐95) | |||||

| Mortality rate Number of deaths (30‐day mortality or in‐hospital mortality) | Study population | RR 0.64 (0.39‐1.06) | 1841 (18 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | Favours combined therapy | |

| 47 per 1000 | 30 per 1000 (18‐49) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 32 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (12‐34) | |||||

| Adverse effects of endoscopy therapy Adverse effects | Study population | RR 1.25 (0.4‐3.96) | 1281 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderateb | No statistically significant difference between groups | |

| 8 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (3‐31) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0‐0) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aModerate statistical heterogeneity was present. bRelatively few events.

Background

Description of the condition

Peptic ulcers develop when the usual protective mechanism of the body breaks down and digestive juices produced in the stomach, intestines and digestive glands damage the lining of the stomach or duodenum. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and Helicobacter pylori are the most common causes of peptic ulcer.

Bleeding peptic ulcer is a serious condition in which ulcers in the upper digestive system (stomach) and the small intestine (duodenum) start to bleed extensively (haemorrhage). The bleeding can be life threatening and requires emergency treatment.

Patients usually require an endoscopy during the first 24 hours after admission so clinicians can locate the source of bleeding (Cooper 1999). Patients with active bleeding or non‐bleeding visible vessels at endoscopy are deemed 'high risk,' as this finding predicts risk of further bleeding and guides management decisions. Once the source of bleeding has been identified, endoscopic therapy reduces rebleeding rate, need for surgery and morbidity and mortality among patients bleeding from a peptic ulcer (Cook 1992).

Endoscopic therapy should be provided to patients with stigmata of high risk (Laine 2012). Such high‐risk patients receive endoscopic therapy consisting of an agent to stop the bleeding, which is injected into the bleeding area. Injection of epinephrine is the most popular method used to stop bleeding. Second endoscopic methods may include bipolar electrocoagulation, heater probe, sclerosant or clips. At the time of publication of the first version of this review, some experts disagreed on the need for a second procedure immediately after epinephrine; although it seems to reduce further bleeding, the effects of a second procedure on continuing illness (morbidity), surgery rates and death (mortality) remain unclear.

Description of the intervention

Many different endoscopic haemostatic techniques have been developed and studied over the past 25 years. Methods are based on injection of vasoconstrictor substances (epinephrine), sclerosant substances (polidocanol, absolute alcohol), clotting factors (thrombin, fibrin glue) or adhesives (cyanoacrylate). Thermal therapies include laser, monopolar electrocoagulation, argon plasma coagulation, bipolar probes and heater probe. More recently, use of mechanical devices to clip the bleeding vessel (haemoclip) has been incorporated. Epinephrine injection—alone or in combination with another technique—has become the most popular endoscopic method for emergency endoscopic haemostasis because of its safety, low cost and easy application (Savides 2000).

Previous guidelines suggested that no clear evidence shows that any technique is superior to injection of epinephrine alone for the endoscopic treatment of high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers (British Society 2002; Feu 2003; Laine 2009). However, some individual studies have reported a significant reduction in further bleeding rates with the addition of a second endoscopic treatment (Chung 1997; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Lin 1999; Lo 2006). Although absolute improvements in haemostatic efficacy were relatively small (from 10% to 20%), they represent a 30% to 60% reduction in the relative risk of recurrent haemorrhage.

At the time of publication of the first version of this review, although some randomised studies had established that epinephrine in combination with a second haemostatic technique is better than epinephrine alone, guidelines available at the time did not provide clear recommendations on this point (British Society 2002; Feu 2003). The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) suggests that combination therapy is better than epinephrine alone for the treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding (ASGE 2004). After publication of the first version of our review in The Cochrane Library (Vergara 2007), further reviews recommended combined treatment for high‐risk peptic ulcer (Kovacs 2008; Peter 2008). Since then, updated guidelines for acute non‐variceal bleeding have been produced. The ASGE has recommended that if "epinephrine is used to treat peptic ulcer bleeding with high‐risk stigmata, a second endoscopic treatment modality (co‐aptive thermal device, sclerosants, thrombin/fibrin glue or clips) should also be used" (Hwang 2012). This is also stated in UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline, which indicates that epinephrine should not be used alone for the treatment of bleeding, but it should be used in combination with a mechanical method, thermal coagulation or fibrin or thrombin (NICE 2012). Repeat endoscopy, with treatment as appropriate, should be considered for all patients at high risk of rebleeding, particularly if doubt exists about adequate haemostasis at the first endoscopy. The American College of Gastroenterology (AGA) Guideline of 2012 (Laine 2012) suggested that patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding should undergo endoscopy within 24 hours of admission, with stigmata of recent haemorrhage recorded, as they predict risk of further bleeding (using the Forrest classification). Endoscopic therapy should be provided to patients with active spurting or oozing bleeding and to those with a non‐bleeding visible vessel. A strong recommendation with high‐quality evidence suggests that epinephrine therapy should be used in combination, as epinephrine monotherapy is less effective than other monotherapies in preventing further bleeding. The second treatments recommended include thermal therapy and injection of a sclerosant. Clips were recommended, as they appear to decrease further bleeding and the need for surgery, although the guidance does state that "comparisons of clips versus other therapies yield variable results and currently used clips have not been well studied." The guidance goes further and states that "for the subset of patients with actively bleeding ulcers, thermal therapy or epinephrine plus a second modality may be preferred over clips or sclerosant alone to achieve initial haemostasis." Routine second‐look endoscopy was not recommended in this guideline.

Why it is important to do this review

Although use of a second endoscopic procedure for the treatment of high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers is now accepted, the addition of a second endoscopic technique can increase cost and risk of complications of the procedure; therefore we investigated whether a reduction in further bleeding actually offsets these drawbacks.

In this updated review, we wanted to ensure that we included all recently published studies of epinephrine injection versus epinephrine and a second endoscopic method for treatment of high‐risk bleeding ulcers.

Objectives

To determine whether a second procedure improves haemostatic efficacy or patient outcomes or both after epinephrine injection in adults with high‐risk bleeding ulcers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials.

Types of participants

Patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers, that is, patients with haemorrhage from peptic ulcer disease (gastric or duodenal) with major stigmata of bleeding as defined by Forrest classification: Ia (spurting haemorrhage), Ib (oozing haemorrhage), IIa (non‐bleeding visible vessel) and IIb (adherent clot) (Forrest Ia‐Ib‐IIa‐IIb) (Forrest 1974).

Types of interventions

Epinephrine injection versus epinephrine injection and a second endoscopic method.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Rebleeding rates (persistent bleeding and recurrent bleeding) as confirmed by endoscopy and further clinically significant bleeding as defined according to the criteria established in each study.

Secondary outcomes

Surgery rate.

Mortality rate.

Adverse effects.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the first published version of this review, we searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which includes the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Group (UGPD) Trials Register) (2006, Issue 1).

MEDLINE (1966 to February 2006).

EMBASE (1980 to February 2006).

We also searched the reference lists of articles.

We contacted experts in the field.

We searched the following databases in 2009.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which includes the Cochrane UGPD Group Trials Register) (2009, Issue 1).

MEDLINE (2006 to September 2009).

EMBASE (2006 to September 2009).

For our update in 2014, we searched the following versions of the databases, limited from June 2009 to May 2014.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to May Week 2 2014 (Appendix 1).

Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily Update May 22, 2014.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations May 22, 2014.

EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials April 2014 (Appendix 2).

EMBASE 1980 to Week 20 2014 (Appendix 3).

The search strategy for this review was constructed by using a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and text words related to the use of epinephrine injection alone and epinephrine injection with a secondary endoscopic therapy for the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. Articles published in any language were included.

To identify RCTs, the search strategy in Appendix 1 (MEDLINE) was combined with recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists from trials selected by electronic searching to identify further relevant trials and published abstracts from conference proceedings from United European Gastroenterology Week (published in Gut) and Digestive Disease Week (published in Gastroenterology).

We also contacted members of the Cochrane UGPD Group and experts in the field to provide details of outstanding clinical trials and relevant unpublished materials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors separately evaluated potentially included studies, that is, studies designed to compare the efficacy of different endoscopic methods to achieve definitive haemostasis in patients with peptic ulcer.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (XC and MV) extracted data, which were reviewed by a third review author (JPG). When results were discordant, papers were jointly reviewed until differences were resolved. For this update, CB and MV reviewed updated search results, selected new trials for inclusion, extracted data separately and conferred over discrepancies until consensus was achieved. CB and MV updated the text of the review.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In this updated version of the review, we introduced the risk of bias table to assess study quality. Consistent with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), this version of the review incorporates additional elements into 'Risk of bias' tables that were not included in the previous published review. Two review authors (MV with XC, MV with CB) independently assessed study quality. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used in comparisons. We used a random‐effects model for analyses. We performed subanalysis for further bleeding to examine the efficacy of different techniques (sclerosant agents, mechanical haemostasis and thermal devices) associated with epinephrine injection versus epinephrine alone.

Unit of analysis issues

Randomisation of clusters can result in overestimation of the precision of results (with higher risk of a Type I error) when their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. None of the included studies employed cluster randomisation. For studies that included more than one active intervention group and only one control group, we selected the interventions that most closely matched our inclusion criteria and excluded the others (Chapter 16.5.4, Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

When data were not available in published trial reports, or when clarification was needed, we contacted trial investigators to request missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The extent to which variations were noted in methods, populations, interventions or outcomes was assessed. Consistency of results was assessed by visual inspection of the forest plot and by examination of I2 (Higgins 2002), a quantity that describes the approximate proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error.

Some clinical heterogeneity was noted across the included studies (see Description of studies), as was some statistical heterogeneity for outcomes for which it was possible to combine study data. Quantitative syntheses of the data therefore were undertaken using a random‐effects model.

Data synthesis

Main comparisons contrasted epinephrine injection versus epinephrine injection plus another haemostatic method. The primary outcome variable was further bleeding, defined as persistence or recurrence of bleeding during follow‐up. We analysed emergency surgery during hospitalisation and morbidity and mortality rates. All results were obtained using Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014). The statistical tests and formulae implemented in RevMan are described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subanalysis was also performed according to the type of peptic ulcer haemorrhage observed: active spurting or oozing (Forrest Ia or Ib), non‐bleeding visible vessel (Forrest IIa) or adherent clot (Forrest IIb). We split further bleeding rates into failure to achieve initial haemostasis and recurrence during follow‐up and analysed the data separately. Finally, to ascertain the influence of second‐look endoscopy on the results, we analysed separately studies that performed this procedure. We also conducted separate analyses depending on the second type of endoscopic technique associated with epinephrine (thermal, sclerosant or mechanical).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

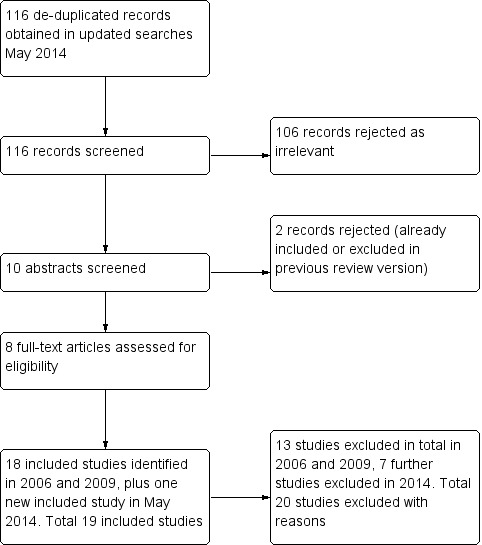

Previous searches in 2006 and 2009 identified 18 included studies and 13 excluded studies.The updated search in May 2014 identified 116 new citations (MEDLINE 45, EMBASE 83, CENTRAL 19); eight potentially relevant records were obtained and scrutinised; seven of these reports did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Characteristics of excluded studies) and had to be excluded. One new trial met the inclusion criteria and was included (Figure 1). Review authors identified a total of 19 included studies and 20 excluded studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

For this update, we included one new study (Grgov 2012). Nineteen articles compared epinephrine injection versus epinephrine plus any other endoscopic method for the endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996). A total of 2033 initially randomly assigned participants were included. Grgov 2012 was published in Serbo‐Croatian, and Garrido 2002 in Spanish. Two studies were published as abstracts only (Lee 1997; Villanueva 1996).

Design

All included studies were RCTs, as specified in our inclusion criteria. Two studies were published as abstracts (not as papers). Sixteen studies used a two‐arm trial design (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996); only three studies (Chung 1999; Lin 1999; Sollano 1991) used a three‐arm trial design.

Participants

Characteristics of the participants in each study were recorded, including numbers of participants, age and gender of participants, percentage of duodenal and gastric ulcers and Forrest type.

The number randomly assigned varied from 276 participants in Chung 1997 to 42 participants in Loizou 1991 (the smallest trial). Eleven studies initially randomly assigned fewer than 100 participants (Balanzo 1990; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996).

Study participants were adults with a mean age greater than 54 years. Age was not reported in Lee 1997, Sollano 1991 or Villanueva 1996. A predominance of male participants was noted in all included studies. Lee 1997, Sollano 1991 and Villanueva 1996 did not report the male‐to‐female ratio. More duodenal than gastric ulcers were included in the trials that reported this characteristic; Lee 1997 and Villanueva 1996 did not report this characteristic.

The Forrest classification of type of bleeding group was reported in all studies, but only 13 studies (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993) reported ulcers categorised by type of bleeding.

Further details of each study can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

Interventions

We recorded any dosage of epinephrine and second endoscopic treatment applied. Medical treatments given as adjuncts were different in each study or were not specified. However, the best treatment for haemorrhage from peptic ulcer is the endoscopic treatment that we analysed in the meta‐analysis.

Twelve studies compared epinephrine versus epinephrine plus a second injected agent. The second injected agents were thrombin in Balanzo 1990 and Kubba 1996; fibrin glue in Pescatore 2002; ethanolamine in Choudari 1994; sodium tetradecyl sulphate in Chung 1993; ethanol in Chung 1996, Lee 1997 and Lin 1993; polidocanol in Garrido 2002, Villanueva 1993 and Villanueva 1996; and ethoxy sclerol in Sollano 1991.

Three studies compared epinephrine versus epinephrine plus heat: Chung 1997 used a heat probe, Lin 1999 used bipolar electrocoagulation and Loizou 1991 employed neodymium‐doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser photocoagulation. The remaining four studies used a mechanical method such as haemoclips (Lo 2006; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012) or band ligation (Park 2004). The dosage of epinephrine and the method of injection used were stated in the study reports. Two studies used the same dosage of epinephrine in both groups—epinephrine alone or combined treatment—independently of whether the haemorrhage stopped (7.5 mL Choudari 1994; 10 mL Loizou 1991). Another study (Lo 2006) injected epinephrine until haemostasis or to a maximum dose of 20 mL of epinephrine in both groups, independently of achieving haemostasis. The remaining included studies investigated the use of injected epinephrine until haemostasis was achieved. Seven included studies did not specify the dosage (Balanzo 1990; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996). In the remaining studies (Chung 1997; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993), the volume of epinephrine used was reported (Characteristics of included studies).

Ten studies performed one or more scheduled second‐look endoscopies 24 to 72 hours after the initial technique was applied (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1203). When active bleeding or persistent high‐risk stigmata (Forrest Ia‐Ib‐IIa‐IIb) were observed, a second therapeutic procedure was performed. Nine studies did not schedule second‐look endoscopy (Lo 2006; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Persistent and recurrent bleeding

We used the following terms: Persistent bleeding occurs when no initial haemostasis was achieved, and recurrent bleeding is a new bleed after initial haemostasis; in trials in which all participants had successful initial haemostasis, the number relates only to the number with recurrent bleeding (as persistent bleeding cannot occur if initial haemostasis is successful).

In most studies, the primary endpoint was defined as endoscopic therapy failure, that is, a combination of persistent haemorrhage and recurrence during follow‐up (further bleeding). Clinical criteria used for presuming further bleeding differed between studies (Characteristics of included studies). Recurrent bleeding in the outcome 'with second‐look endoscopy' was confirmed endoscopically, and 10 studies reported this outcome (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Lin 1993; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993); otherwise rebleeding rates included both endoscopic and clinically evident rebleeding. Analyses were also performed on included studies that reported data for persistent haemorrhage and recurrence separately during follow‐up.

Fourteen studies reported initial failure of haemostasis and recurrent bleeding separately (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993). The remaining five studies did not distinguish between persistent and recurrent bleeding (Choudari 1994; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1996).

Fourteen studies randomly assigned participants who reported bleeding rates when peptic ulcers were actively bleeding (spurting Forrest Ia or oozing Forrest Ib) (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993).

Nine studies with a total of 448 participants provided data on peptic ulcers with a non‐bleeding visible vessel (Forrest IIa) (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993). Only four studies (Lo 2006; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Pescatore 2002) included participants with adherent clot (Forrest IIb), although Lo 2006 and Grgov 2012 did not report results according to Forrest category, and therefore results from only 30 participants appear in our analyses.

Secondary outcomes

Surgery and mortality

Criteria for emergency surgery were not specified in most studies. Thirty‐day mortality and in‐hospital mortality were the criteria used most often for defined mortality (Characteristics of included studies).

The need for emergency surgery was evaluated in 18 studies (1841 participants) (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996). Garrido 2002 did not specify surgery rates in each group, only total rate.

The criteria for mortality rate were also different between studies. Some studies used hospital mortality; others used 30‐day mortality or did not specify the criteria for mortality. The mortality rate was evaluated in 18 studies (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996); only Garrido 2002 did not report mortality.

In addition, 12 studies reported complications that occurred in the study population (Lo 2006; Chung 1993; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993).

Excluded studies

A total of 20 studies were excluded from the review; 13 were excluded before this update was performed (Buffoli 2001; Chua 2001; Chung 1990; Chung 1992; Chung 1997a; De Goede 1998; Dedeu 2003; Ell 2002; Gevers 2002; Male 1999; Pescatore 1999; Sabat 1998; Wehrmann 1994), and we excluded a further seven studies in 2014 (Chittmittrapap 2010; Grgov 2013; Karaman 2011; Lecleire 2009; Ljubicic 2012; Taghavi 2009; Tsoi 2009). The main reasons for exclusion of studies were as follows: non‐randomised studies (Buffoli 2001; Chittmittrapap 2010; Chua 2001; Tsoi 2009); preliminary results published later in another article (Chung 1990; Chung 1992; Chung 1997a; De Goede 1998; Male 1999; Pescatore 1999); impossible to extract data (Dedeu 2003; Ell 2002); did not fit our criteria for intervention, that is, did not compare epinephrine alone versus epinephrine plus a second agent (Gevers 2002; Grgov 2013; Karaman 2011; Ljubicic 2012; Taghavi 2009); participants did not fit our inclusion criteria (Lecleire 2009); or important methodological problems were noted within the study (Sabat 1998; Wehrmann 1994) (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

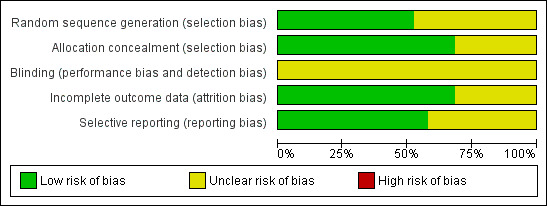

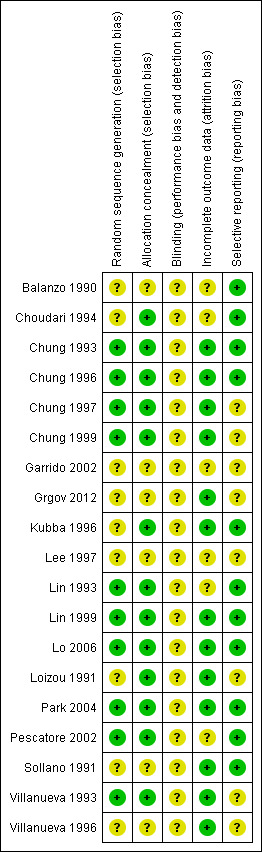

A summary of the risk of bias across studies is given in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation was adequately described in only 10 of the included studies (Lo 2006; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993) and was judged as unclear in the remaining studies. Allocation concealment was adequate in 13 studies and was judged as unclear in six studies (Balanzo 1990; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Lee 1997; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1996).

Blinding

The studies were not double blind because the endoscopist must know the technique to be applied.

Incomplete outcome data

Only six studies were judged as unclear for incomplete outcome data (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Garrido 2002; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Pescatore 2002); all remaining studies were judged as having low risk of bias.

Selective reporting

A total of 11 studies were rated as having low risk of bias for selected outcome reporting (Balanzo 1990; Lo 2006; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Kubba 1996; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991). The remaining studies were rated as having unclear risk of bias. However in the absence of initial study protocols, it is not clear whether all studies reported outcomes as prespecified in the trial protocol.

Other potential sources of bias

Other potential sources of bias were noted in the design of studies in terms of interventions used and outcomes assessed. The different treatment strategies used could bias results, as some may appear more favourable in terms of achieving haemostasis, such as the technique used by Lo 2006, in which epinephrine was injected until haemostasis was achieved or until a maximum dose of 20 mL of epinephrine was given in both groups, independently of achieving haemostasis. It is difficult, however, to establish whether this method could decrease the frequency of recurrence.

Some studies used different definitions of haemorrhage. However, all studies included in the meta‐analysis that reported rebleeding criteria were very similar, suggesting that the definition of rebleeding was not a source of bias. As explained, outcome criteria in all studies were very similar, so we believe that these data did not bias study results.

The mortality rate was also different between studies using different criteria. Some studies used hospital mortality, while others used 30‐day mortality or did not specify the criteria for mortality. This made comparison of mortality rates difficult and hindered conclusions about the rate of mortality resulting from haemorrhage in people with ulcers. Moreover, data on previous morbidity among study participants often were not provided in study reports.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We use the following terms: Persistent bleeding occurs when no initial haemostasis is achieved, and recurrent bleeding is a new bleed after initial haemostasis. In trials in which all had successful haemostasis, the number relates only to the number with recurrent bleeding (as bleeding cannot be persistent if the initial haemostasis is successful).

In the text below, an I² statistical value for heterogeneity is reported as follows: 30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity; 75% to 100%: shows considerable heterogeneity.

Numbers given show the total numbers of participants in the analysis. When it was possible to calculate an effect size, these values were reported with 95% confidence intervals. When the calculated effect size was statistically significant (P value < 0.05), we stated whether the result favours the intervention or the control condition.

We have summarised results below under headings corresponding to the primary and secondary outcomes outlined in the section entitled Types of outcome measures.

COMPARISON 1. Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method

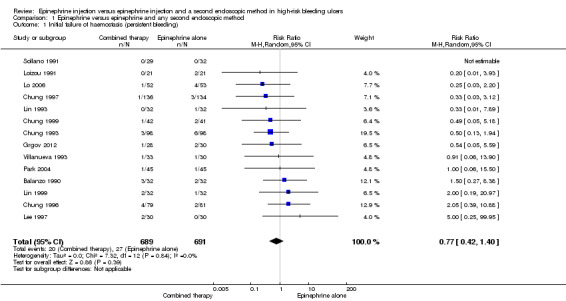

Initial failure of haemostasis (persistent bleeding)

For this outcome, we found 14 relevant trials that provided separate data on participants who did not achieve initial haemostasis (Balanzo 1990; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1380). No significant difference was noted between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method (RR random 0.77, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.4; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 1 Initial failure of haemostasis (persistent bleeding).

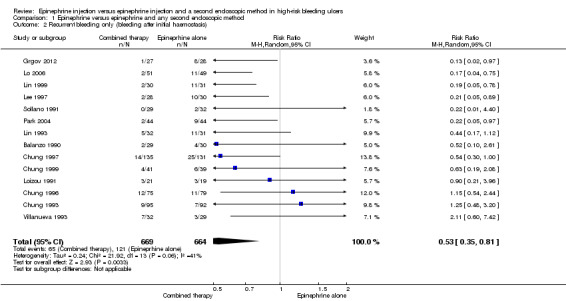

Recurrent bleeding only (bleeding after initial haemostasis)

For this outcome, we found 14 relevant trials (Balanzo 1990; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1333). A statistically significant difference was reported between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method favouring combined therapy (RR random0.53, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.81, P value 0.03; Analysis 1.2). This outcome had moderate levels of heterogeneity (Chi2 = 21.92, df = 13, P value 0.06, I2 = 41%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 2 Recurrent bleeding only (bleeding after initial haemostasis).

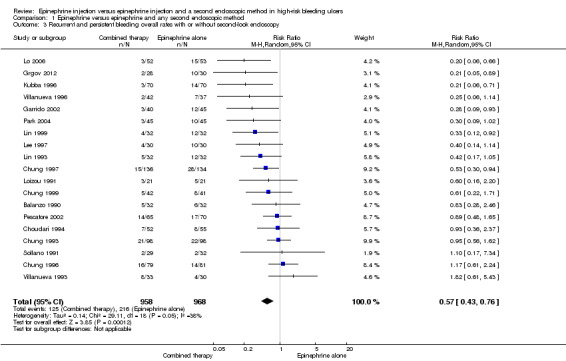

Recurrrent and persistent bleeding overall rates with or without second‐look endoscopy

All articles that compared substances administered by endoscopic injection (sclerosants such as ethanol, polidocanol, ethanolamine or tetradecyl sulphate; adhesive agents such as cyanoacrylate; and thrombotic substances such as fibrin glue or thrombin), epinephrine plus thermal agents and epinephrine plus a mechanical method such as clips were analysed together. All studies reported this outcome, that is, clinically diagnosed and/or endoscopically confirmed rebleeding (19 relevant trials; Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996) (n = 1926). A statistically significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method favoured combined therapy (RR random 0.57, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.76, P value 0.0001; Analysis 1.3). This outcome had moderate levels of heterogeneity (Chi2 = 29.11, df = 18, P value 0.05, I2 = 38%).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 3 Recurrent and persistent bleeding overall rates with or without second‐look endoscopy.

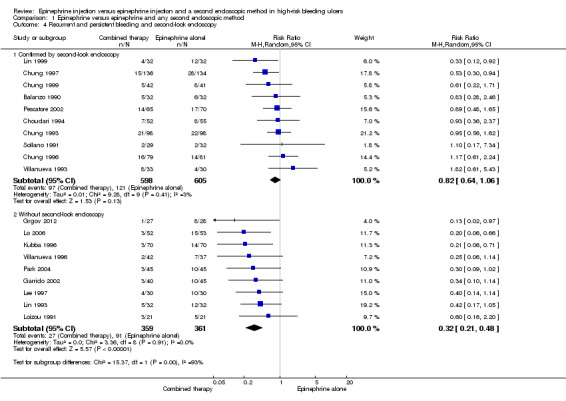

Recurrent and persistent bleeding and second‐look endoscopy

With second‐look endoscopy (endoscopically confirmed persistent or recurrent bleeding)

Ten studies performed one or more scheduled second‐look endoscopies 24 to 72 hours after the initial technique was applied (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1203). When active bleeding or persistent high‐risk stigmata (Forrest Ia‐Ib‐IIa‐IIb) were observed endoscopically, a second therapeutic procedure was performed. No significant difference was noted between the numbers with endoscopically confirmed rebleeding in the epinephrine group and in the epinephrine and second endoscopic method groups (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.06; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 4 Recurrent and persistent bleeding and second‐look endoscopy.

Without second‐look endoscopy

Nine studies did not schedule second‐look endoscopy (Lo 2006; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996) (n = 720). A statistically significant difference in the numbers of participants with rebleeding (clinically diagnosed and endoscopically confirmed) between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method favoured combined therapy (RR random 0.32, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.48, P value < 0.00001; Analysis 1.4).

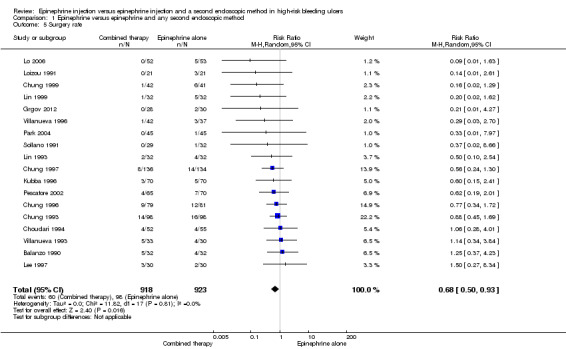

Surgery rate

For this outcome, we found 18 relevant trials that reported the numbers of participants who needed surgical intervention on an emergency basis because initial haemostasis could not be obtained, or because rebleeding occurred (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996) (n = 1841). A statistically significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method favoured combined therapy (RR random 0.68 95% CI 0.50 to 0.93, P value 0.02; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 5 Surgery rate.

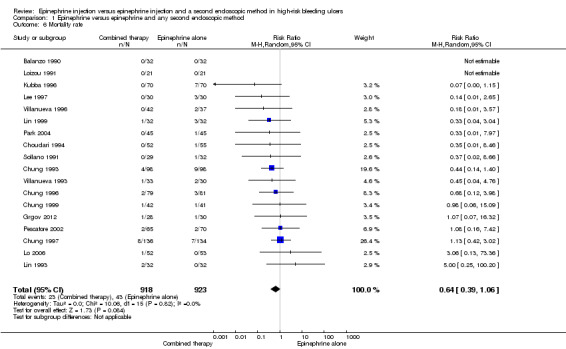

Mortality rate

For this outcome, we found 18 relevant trials reporting mortality as death in hospital or as a result of bleeding peptic ulcer (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993; Villanueva 1996) (n = 1841). No significant difference was noted between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method (RR random 0.64, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.06; Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 6 Mortality rate.

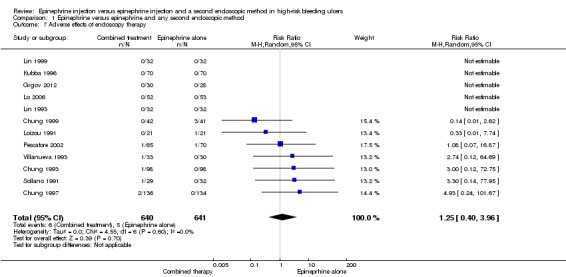

Adverse effects of endoscopic therapy

For this outcome, we found 12 relevant trials that reported whether complications had occurred and the types of complications reported (Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Grgov 2012, Kubba 1996; Lin 1993; Lin 1999; Lo 2006; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1281). No significant difference was noted between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method (RR random 1.25, 95% CI 0.4 to 3.96; Analysis 1.7). Details of adverse effects encountered (found in Table 2) included perforations, mucosal injury and necrosis. Induction of massive bleeding requiring surgery was more frequent in the epinephrine only group (n = 5); necrosis appeared in three participants (two in the combined therapy group and one in the epinephrine alone group), and perforation (three participants) was observed in the combined therapy group. Thus, adverse events were slightly more frequent in the combined therapy group (6/610 participants) than in the epinephrine alone group (5/648 participants), although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 7 Adverse effects of endoscopy therapy.

1. Procedure‐related adverse effects.

| Study ID | Adverse effects in epinephrine plus second agent group (combined therapy) | Adverse effects in epinephrine group |

| Lo 2006 | None | None |

| Chung 1993 | Quote, page 613: "A 75‐year‐old man in the epinephrine plus STD group had abdominal pain after injection therapy. An actively bleeding pre‐pyloric ulcer had been injected with 8 ml of epinephrine followed by 1 ml of STD. Signs of upper abdominal peritonitis developed 36 hours later. At operation extensive infarction and necrosis were seen along the lesser curvature of the stomach. The right gastric artery was cord‐like and thrombosed along its course. Extensive coagulative necrosis was observed in the arteries in the muscularis propria. It is likely that the STD was injected directly into the right gastric artery and travelled in the artery along the lesser curvature. It caused coagulative necrosis in the smaller arteries and necrosis along the lesser curvature of the stomach. Fortunately, the patient made an uneventful recovery after a subtotal gastrectomy" | No untoward cardiovascular events were observed during endoscopic injection therapy in either group. |

| Chung 1997 | Two participants underwent surgery for perforations related to heat probe application | None |

| Chung 1999 | No 'notable' complications were reported in the haemoclip and combined therapy groups | Three participants. In 1 case, bleeding was aggravated during treatment of a non‐bleeding visible vessel, and surgical intervention for control of bleeding ultimately was required. In the other 2 cases, submucosal haematoma developed |

| Grgov 2012 | None | None |

| Kubba 1996 | None | None |

| Lin 1993 | None | None |

| Lin 1999 | None | None |

| Loizou 1991 | None | Text states no procedure‐related complications, but in 1 participant in the epinephrine group, injection provoked spurting haemorrhage |

| Pescatore 2002 | Perforation (leading to surgical intervention) (n = 1) Non–procedure‐related complications: pneumonia (n = 1) |

Ulcer haemorrhage (n = 1 patient in group E) induced by epinephrine injection that led to surgical intervention. Non–procedure‐related complications were reported: pneumonia (n = 3); stroke (n = 1) |

| Sollano 1991 | Mucosal injury or necrosis (n = 1) | Mucosal injury or necrosis (n = 1) |

| Villanueva 1993 | Size of ulcer increased 5‐fold after infection, developed pneumoperitoneum, resolved spontaneously | None |

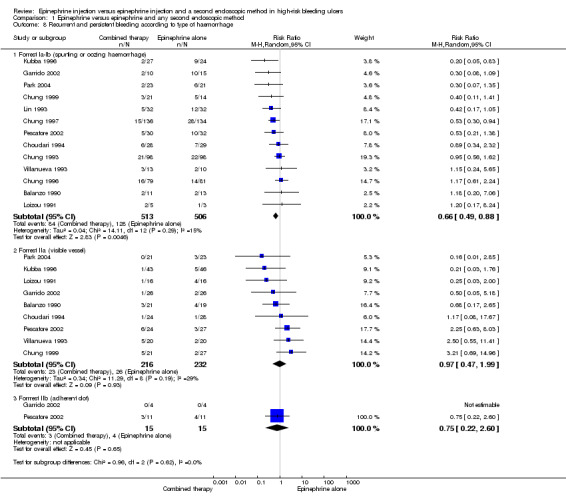

Recurrent and persistent bleeding according to type of haemorrhage

Forrest Ia‐Ib (spurting or oozing haemorrhage)

Thirteen studies with a total of 1019 participants reported bleeding rates when peptic ulcers were actively bleeding (spurting Forrest Ia; oozing Forrest Ib) We included participants who had confirmed bleeding by endoscopy and those who clinically rebled in Analysis 1.8) (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1997; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Lin 1993; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993 (n = 1019). A statistically significant difference favoured the combined therapy group (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.88, P value 0.005, I2 = 15%)

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and any second endoscopic method, Outcome 8 Recurrent and persistent bleeding according to type of haemorrhage.

Forrest IIa (visible vessel)

Nine studies with a total of 440 participants provided data on peptic ulcers with a non‐bleeding visible vessel (Forrest IIa) (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Loizou 1991; Park 2004; Pescatore 2002; Villanueva 1993). No significant difference was reported between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.99, I2 = 29%; Analysis 1.8).

Forrrest IIb (adherent clot)

Only four studies (Lo 2006; Garrido 2002; Grgov 2012; Pescatore 2002) included participants with adherent clot (Forrest IIb). Lo 2006and Grgov 2012 did not provide results on different Forrest groups included in the study and so were not included in this analysis. In the epinephrine alone group, 4/15 (26.7%) presented further bleeding versus 3/15 (20%) in the combined therapy group. In this subgroup, we found two relevant trials (n = 30). No significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second endoscopic method was noted (RR random 0.75, 95% CI 0.22 to 2.6; Analysis 1.8).

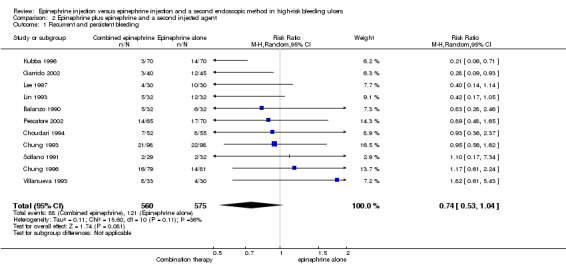

COMPARISON 2. Epinephrine plus epinephrine and a second injected agent

Recurrent and persistent bleeding

For this outcome, we found 11 RCTs (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Garrido 2002; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1135); no statistically significant difference favoured combination therapy (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.04, P value 0.08; Analysis 2.2). This outcome had moderate levels of heterogeneity (Chi2 = 15.66, df = 10, P value 0.11, I2 = 36%).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epinephrine plus epinephrine and a second injected agent, Outcome 2 Surgery rate.

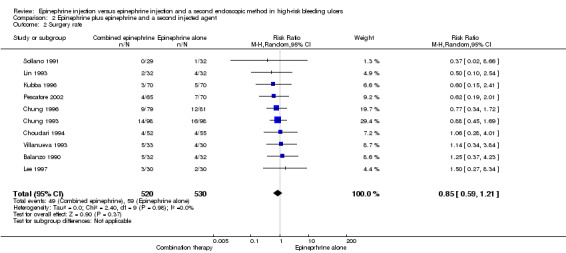

Surgery rate

For this outcome, we found 10 RCTs (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1050) (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.21; Analysis 2.2). No significant differences were noted between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second injected agent.

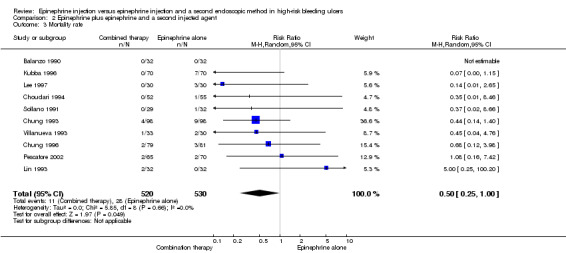

Mortality rate

For this outcome, we found 10 RCTs (Balanzo 1990; Choudari 1994; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Kubba 1996; Lee 1997; Lin 1993; Pescatore 2002; Sollano 1991; Villanueva 1993) (n = 1050) (RR 0.5, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.0; Analysis 2.3). A statistically significant difference was reported between epinephrine and epinephrine and any second injected agent.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Epinephrine plus epinephrine and a second injected agent, Outcome 3 Mortality rate.

COMPARISON 3. Epinephrine versus epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods

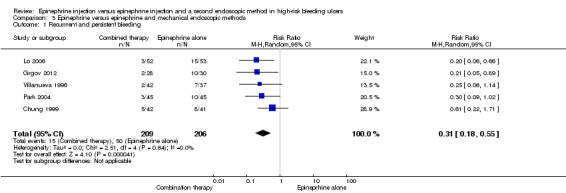

Recurrrent and persistent bleeding

For this outcome, we found five relevant trials that reported the efficacy of adding a mechanical haemoclip to epinephrine injection (Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lo 2006; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996) (n = 415). A statistically significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods favoured epinephrine plus a mechanical method (RR random 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.55, P value < 0.0001; Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods, Outcome 1 Recurrrent and persistent bleeding.

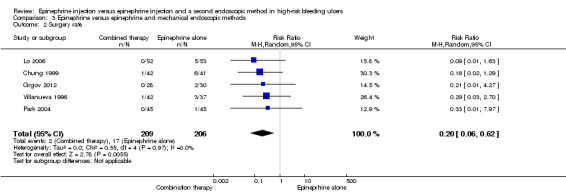

Surgery rate

Five RCTs provided data on surgery rate (Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lo 2006; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996) (n = 415). A statistically significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods favoured epinephrine plus a mechanical method (RR random 0.2, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.62, P value 0.005; Analysis 3.2).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods, Outcome 2 Surgery rate.

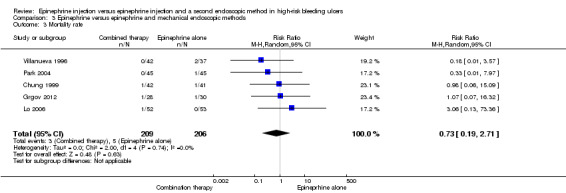

Mortality rate

Mortality rate was provided in five RCTs (Chung 1999; Grgov 2012; Lo 2006; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996) (n = 415). No significant difference was noted between epinephrine and epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods (RR random 0.73, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.71; Analysis 3.3).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Epinephrine versus epinephrine and mechanical endoscopic methods, Outcome 3 Mortality rate.

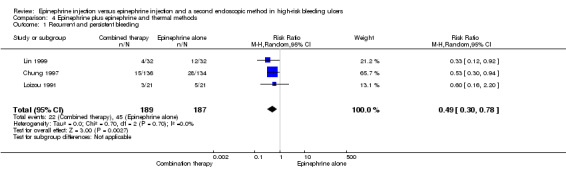

COMPARISON 4. Epinephrine plus epinephrine and thermal methods

Recurrent and persistent bleeding

Three studies compared epinephrine alone versus epinephrine combined with thermal haemostatic methods (contact heat probe, Nd:YAG laser or bipolar electrocoagulation) (Chung 1997; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991) (n = 376) (RR random 0.49, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.78, P value 0.003; Analysis 4.1). A statistically significant difference was observed between epinephrine and epinephrine and thermal endoscopic methods.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epinephrine plus epinephrine and thermal methods, Outcome 1 Recurrent and persistent bleeding.

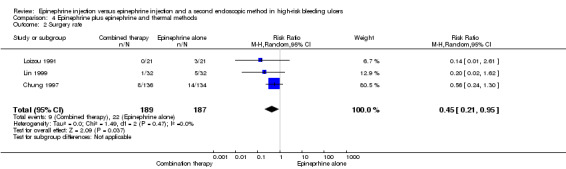

Surgery rate

Surgery rate was given in three trials (Chung 1997; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991) (n = 376), A statistically significant difference between epinephrine and epinephrine and thermal endoscopic methods favoured the combination therapy group (RR random 0.45, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.95, P value 0.04; Analysis 4.2).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epinephrine plus epinephrine and thermal methods, Outcome 2 Surgery rate.

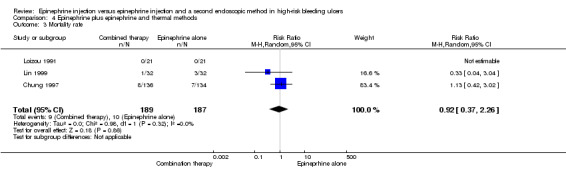

Mortality rate

For this outcome, we found three relevant trials (Chung 1997; Lin 1999; Loizou 1991) (n = 376) (RR random 0.92, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.26; Analysis 4.3). No significant difference was observed between epinephrine and epinephrine and thermal endoscopic methods.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Epinephrine plus epinephrine and thermal methods, Outcome 3 Mortality rate.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Nineteen studies including a total of 2033 initially randomly assigned participants were included, of which 11 used a second injected agent, five used a mechanical method (haemoclips) and three employed thermal methods.

For the comparison of epinephrine versus any second agent, we produced meta‐analyses for eight outcomes. Few participants failed initial haemostasis, and analyses of epinephrine versus epinephrine plus any second method failed to show differences in achieving initial haemostasis between epinephrine alone and epinephrine with a second endoscopic method.

Adding any second procedure significantly reduced rebleeding rates in three analyses, that is, fewer participants in the combined therapies groups experienced recurrent bleeding after initial haemostasis (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.81); fewer participants had persistent and recurrent bleeding (with or without second‐look endoscopy) (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.43 to 0.76) and fewer had persistent or recurrent bleeding (without scheduled second‐look endoscopy) (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.48). No difference in rebleeding rates was seen between groups in studies that did schedule second‐look endoscopy.

The numbers needing emergency surgery were significantly lower in the combined group (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.93), but mortality rates were not significantly different with either method. Adverse events included perforations, mucosal injury and necrosis; these events were few, and no statistically significant difference between groups was noted.

For ulcers of the Forrest Ia or Ib type (oozing or spurting), the addition of a second therapy significantly reduced the rebleeding rate (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.88); this difference was not seen for type IIa (visible vessel) or type IIb (adherent clot) ulcers.

Our analyses therefore showed that the risk of further bleeding was lower in the combination therapy groups than in the epinephrine alone groups, regardless of which second procedure was applied. Failure of endoscopic therapy is the main predictor of the need for surgery and of morbidity and mortality in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer (Brullet 1996). Therefore, it seems highly likely that reduction of further bleeding rates decreased the need for surgery and improved survival.

We also compared epinephrine versus epinephrine plus injected agents, versus epinephrine plus a mechanical method and versus epinephrine plus thermal methods separately.

For the comparison of epinephrine versus epinephrine plus any injected method, we produced meta‐analyses for three outcomes. Fewer participants in the combination group experienced recurrent and persistent bleeding, but this finding was not statistically significant. Fewer participants in the combination therapy group died and this was statistically significant (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.00), but no difference between groups was noted for the number needing emergency surgery.

For the comparison of epinephrine versus epinephrine plus a mechanical method such as haemoclips, results favoured the combination therapy group for recurrent or persistent bleeding (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.55); fewer participants in the combination group needed surgery (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.62), but no statistically significant difference was reported for mortality.

For the comparison of epinephrine versus epinephrine plus a thermal method, results favoured combined therapy for recurrent and persistent bleeding (RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.78) and for surgery (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.26), but no statistically significant difference was reported for mortality.

Our updated review with new data confirms the results published in our previous review (Vergara 2007).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

One limitation of this review is that definitions for haemorrhage, surgery and death were not the same in the different studies (Characteristics of included studies). Marked heterogeneity observed in defining further bleeding among studies precluded the definition of a homogeneous, predetermined criterion for the primary endpoint. We therefore accepted the definition established for each study. Further bleeding definitions are shown in Characteristics of included studies. As the analysis includes only randomised, comparative studies, the criteria were similar for the two groups (epinephrine alone and combined therapy) in each study, thus allowing further comparison. Furthermore, endoscopic confirmation of bleeding was required for studies that reported second‐look endoscopy, thus reducing heterogeneity. Criteria for mortality rate were different between studies. Some studies used hospital mortality as a key, and others used 30‐day mortality or did not specify the mortality criteria applied. This makes it difficult to extract definitive conclusions about mortality rates in haemorrhage from those in ulcer disease. Moreover, characteristics of the co‐morbidities of participants were not included in the results of most of the studies.

Medical treatments were also different between studies or were not specified. However, the best treatment for bleeding from a peptic ulcer is the endoscopic treatment that we analysed in the present meta‐analysis.

One important point to state involves the dosage of epinephrine and the methodological process used in each study. The dosage of epinephrine used was detailed in Characteristics of included studies. Seven included studies did not specify the dosage (Balanzo 1990; Chung 1993; Chung 1996; Chung 1999; Garrido 2002; Park 2004; Villanueva 1996). Two studies used the same dosage of epinephrine for both groups independently of whether haemorrhage stopped (Choudari 1994; Loizou 1991). Another study (Lo 2006) injected epinephrine until haemostasis or to a maximum dose of 20 mL of epinephrine in both groups, independently of achieving haemostasis.

Comparisons of epinephrine versus epinephrine plus a specific second method also raise some unanswered questions. First, although one might consider that the efficacy of injecting a second agent is similar to that achieved with thermal and mechanical methods, this interpretation should be treated with extreme caution. The only conclusion that can be drawn from our meta‐analysis is that, whichever second treatment is used, combined therapy seems to work better than epinephrine alone. However, we cannot conclude that a particular form of treatment is equal or superior to another. Indeed, an earlier meta‐analysis evaluating endoscopic therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers demonstrated that all methods of controlling bleeding in peptic ulcers (thermal devices, injectable agents such as sclerosants and thrombin/fibrin glue and haemoclips) were effective, with no single modality determined to be superior (Laine 2009). There are two main reasons for this. First, the subgroups (further injection, thermal methods or mechanical methods) include different procedures that may present heterogeneous activity. In fact, each endoscopic treatment presents different characteristics: Epinephrine produces vasoconstriction, vessel compression and platelet aggregation, but it does not seem to induce permanent thrombosis in blood vessels (Lin 2002). Sclerosant agents such as polidocanol or ethanol can produce thrombosis of vessels favouring haemostasis, although they may also induce significant tissue injury (Randall 1989; Ritgeers 1989). Whether human thrombin injection could reduce the risk of tissue damage remains unclear, and thrombin is more expensive than other additional treatments (Laine 2003). Thermal agents produce thrombosis of vessels and risk damaging tissue. Among them, laser photocoagulation seems to be associated with higher risks of perforation, optical hazard, high cost and imperfect haemostatic effect. Multi‐polar electrocoagulation and heater probe thermocoagulation have been reported to produce excellent results; they are also less expensive and are more easily portable than laser methods (Llach 1996). Mechanical methods close the vessel. They were also associated with few complications, but technical difficulty was associated with applying the haemoclip to the posterior wall of the proximal body and cardia of the stomach (Grgov 2012), and to the posterior wall of the duodenum, because of the requirement that the haemoclip meet the lesion at a right angle (Chung 1999; Simoens 2001). A meta‐analysis compared haemoclip versus other methods to investigate the possible benefits of haemoclips versus other endoscopic methods. The evidence showed no differences between them (Yuan 2008).

Even more important, the statistical treatments used in our meta‐analyses are not designed to compare additional treatments head to head. In fact, we lack randomised trials comparing different additional treatments after epinephrine injection, although some recent studies are available (e.g. Grgov 2013; Karaman 2011; Taghavi 2009), and we must await analysis of comparative studies to establish which is the best therapy when combined with epinephrine.

Our review did not determine whether combined therapy is better than sclerosants, thermal methods or mechanical methods alone. Little evidence in the literature suggests that this is the case. In a small study, Lin 1999 found that combined therapy seems better than bipolar electrocoagulation alone. Also, a recent meta‐analysis concluded that combined injection is superior to a sclerosant alone (Rollhauser 2000). In any event, the clinical relevance of this question may be minor.

One of the major fears associated with using combined therapy involves the possible risk of gastric wall necrosis or perforation or both. The present meta‐analysis shows that the risk of significant complications is very low. This review failed to find evidence of a difference in complication rates between groups. When the complications are examined in detail, it can be seen that induction of massive bleeding requiring surgery was more frequent in the epinephrine group, whereas gastric wall necrosis or perforation was more common in the combined therapy group. This possible small increase in the risk of perforation or necrosis is clearly compensated for by the benefits derived from reducing further bleeding, which result in a significant decrease in the need for surgery and in mortality; therefore this risk is not a reason for avoiding combined therapy.

Epinephrine injection is cheap, easy to perform and safe. In addition, according to our analysis, epinephrine seems as good as combined therapy for achieving initial haemostasis. By controlling active bleeding, it could allow a better endoscopic view and more accurate targeting of additional therapy. Therefore, medical or economic arguments against epinephrine injection are few.

Quality of the evidence

Of the 19 trials included in this review, some had limitations in design or implementation, but most were clear about important quality criteria including randomisation and allocation concealment, sequence generation and blinding. Our risk of bias estimates show that overall most studies were not at high risk of bias in any of the domains that we assessed. It should be noted that we did not rate performance bias because it is not possible to blind participants and personnel in studies of this nature. Although the type of study did not allow a double‐blind trial (Figure 2), rebleeding, surgery and mortality were not dependent on subjective observation.

The meta‐analysis involved a large number of well‐designed studies, but for most outcomes, the quality of the evidence was rated as moderate, and further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. We summarised the quality of the studies in Summary of findings table 1. When we downgraded the evidence to moderate quality, we did so because few events were reported; this was the case for the outcomes of surgery, mortality and adverse effects. The included studies involved relatively few participants, but larger populations are difficult to achieve in this type of trial. Some imprecision was noted (wide confidence intervals), and the results of some meta‐analyses showed low to moderate levels of statistical heterogeneity (inconsistency). One explanation for this may be the differences noted between trials (populations, definitions of outcomes such as in‐hospital or 30‐day mortality and definitions of rebleeding), as discussed above.

Potential biases in the review process

One limitation of our review is that despite exhaustive searching, it is difficult to be certain that every published and unpublished study was identified. We acknowledge that there is always a risk that some studies were not identified. However for the studies that we identified, the quality was rated as moderate for most outcomes, and because of the serious nature of this condition, incidences of adverse effects were reported in many trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The findings of our updated review are in agreement with the recommendations provided in three major clinical guidelines produced since the first published version of this review. Combined therapy of epinephrine plus a second endoscopic agent (e.g. bipolar electrocoagulation, heater probe, sclerosant, clips) for the treatment of patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers (Laine 2012; NICE 2012; Hwang 2012) is the main recommendation for active bleeding or non‐bleeding visible vessels.

As far as second‐look endoscopy is concerned, one meta‐analysis showed that although scheduled second‐look endoscopies reduced the rebleeding rate, they did not decrease the need for surgery nor mortality (Marmo 2003). It was also suggested that selective second‐look endoscopy for selected high‐risk patients could be a cost‐effective approach (Spiegel 2003). However, this strategy exposes patients to uncomfortable and somewhat risky procedures and increases the workload of the endoscopy unit. Results of the present study did not confirm that second‐look endoscopy diminished the risk of rebleeding. For all of these reasons, it remains unclear whether second‐look endoscopy offers any added benefit to combined therapy associated with proton pump inhibitor infusion. This finding is in agreement with current guidelines on the management of acute non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. In the NICE 2012 guideline, the recommendation is to "consider a repeat endoscopy, with treatment as appropriate" (further endoscopic treatment or emergency surgery),"for all patients at high risk of re‐bleeding, particularly if there is doubt about initial haemostasis at the first endoscopy." The AGA guideline (Laine 2012) does not recommend routine second‐look endoscopy 24 hours after initial endoscopic haemostatic therapy but says that this should be offered for patients with clinical evidence of recurrent bleeding, and in these cases, haemostatic therapy should be applied for those with greater risk of stigmata of haemorrhage. Routine second‐look endoscopy, defined as a planned endoscopy performed within 24 hours of the initial endoscopy, in patients who have received adequate endoscopy is not recommended by the ASGE in its 2012 guideline (Chung 1999; Hwang 2012).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The present study shows that adding a second endoscopic procedure after epinephrine injection reduces the rate of recurrence in patients with high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcer. This study also shows that adding any second endoscopic method reduces the need for surgery. In view of the evidence, and while we await the results of further studies, combined therapy should be considered the standard procedure in high‐risk peptic ulcer haemorrhage (Forrest Ia, Ib, IIa).

Implications for research.

The current evidence shows that addition of a second endoscopic method to epinephrine injection is better than epinephrine injection alone in high‐risk bleeding peptic ulcers, in terms of preventing both rebleeding and the need for emergency surgery. Future research should investigate the best endoscopic method that, when associated with epinephrine, achieves low rebleeding rates, reduced need for surgery and prevention of mortality and procedure‐related adverse effects when standardised outcome criteria such as use of a scheduled second endoscopy and criteria for rebleeding are used, and whether this was confirmed endoscopically. Further systematic reviews and meta‐analyses should assess such head‐to‐head comparisons to compare the efficacy of additional treatments.

Other therapeutic approaches, such as use of a high‐dose proton pump inhibitor or second‐look endoscopy, could influence the efficacy of combined therapy. Use of high‐dose proton pump inhibitors for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers is gaining acceptance. Evidence clearly suggests that these drugs reduce the risk of rebleeding (Gisbert 2001). However, many points remain unclear, such as the cost‐effectiveness of this approach, the ideal drug dosage to be used and whether this strategy should be reserved for patients at high risk of rebleeding. Both combined endoscopic therapy and proton pump inhibitor infusion are safe and comfortable for the patient. Therefore, although the extent of the benefit of combining the two approaches remains uncertain, this strategy seems reasonable until additional evidence becomes available.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 30 May 2014 | New search has been performed | Updated with new search results, 1 new trial added |

| 30 May 2014 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | New author (CB); new, updated results |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2006 Review first published: Issue 2, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 November 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated. |

| 16 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 January 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

| 6 January 2007 | Amended | Minor update. |

| 14 February 2006 | Amended | New studies found and included or excluded. |

Notes

None.

Acknowledgements

Discussions by the group that developed the Catalan Guidelines for non‐variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding were invaluable in helping to determine gaps in knowledge on bleeding peptic ulcer treatment. We are indebted to all participants, especially to Dr Faust Feu as the co‐ordinator of this group.

We thank Dr Nadja Smailagic, who provided translations of Grgov 2012 and Grgov 2013.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to May Week 2 2014, Ovid MEDLINE(R) Daily Update May 22, 2014, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations May 22, 2014

randomized controlled trial.pt.

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomized.ab.

placebo.ab.

drug therapy.fs.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

groups.ab.

or/1‐8

exp animals/ not humans.sh.

9 not 10

exp peptic ulcer/

exp peptic ulcer hemorrhage/

exp peptic ulcer perforation/

exp duodenal ulcer/

exp stomach ulcer/

(pep$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(stomach adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(duoden$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(gastr$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(rebleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(recurrent adj5 bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(acute adj5 bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

exp gastrointestinal hemorrhage/

(gastrointestinal adj5 bleed$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 rebleed$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 hemorrhag$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 haemorrhag$).tw.

(ulcer adj5 hemorrhag$).tw.

(ulcer adj5 haemorrhag$).tw.

(mucos$ adj5 injur$).tw.

(mucos$ adj5 ero$).tw.

(gastr$ adj5 ero$).tw.

(stomach adj5 ero$).tw.

or/12‐35

exp epinephrine/

epinephrine.tw.

exp vasoconstrictor agents/

or/37‐39

(argon adj5 plasma adj5 coagulat$).tw.

exp sclerotherapy/

sclerotherap$.tw.

exp electrocoagulation/

exp hemostasis/

exp hemostasis, endoscopic/

exp lasers/

exp endoscopy gastrointestinal/

electrocoagulat$.tw.

(therm$ adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(heater adj5 probe).tw.

laser$.tw.

endoclip$.tw.

hemoclip$.tw.

(monopolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(multipolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(bipolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

exp sclerosing solutions/

sclerosant$.tw.

polidocanol.tw.

exp polyethylene glycols/

(endoscopic adj3 inject$).tw.

thrombin.tw.

fibrin glue.tw.

exp fibrin tissue adhesive/

cyanoacrylate.tw.

exp enbucrilate/

or/41‐67

36 and 40 and 68

11 and 69

limit 70 to ed=20090601‐20140523

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials April 2014

exp peptic ulcer/

exp peptic ulcer hemorrhage/

exp peptic ulcer perforation/

exp duodenal ulcer/

exp stomach ulcer/

(pep$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(stomach adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(duoden$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(gastr$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(rebleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(recurrent adj5 bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

(acute adj5 bleed$ adj5 ulcer$).tw.

exp gastrointestinal hemorrhage/

(gastrointestinal adj5 bleed$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 rebleed$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 hemorrhag$).tw.

(gastrointestinal adj5 haemorrhag$).tw.

(ulcer adj5 hemorrhag$).tw.

(ulcer adj5 haemorrhag$).tw.

(mucos$ adj5 injur$).tw.

(mucos$ adj5 ero$).tw.

(gastr$ adj5 ero$).tw.

(stomach adj5 ero$).tw.

or/1‐24

exp epinephrine/

epinephrine.tw.

exp vasoconstrictor agents/

or/26‐28

(argon adj5 plasma adj5 coagulat$).tw.

exp sclerotherapy/

sclerotherap$.tw.

exp electrocoagulation/

exp hemostasis/

exp hemostasis, endoscopic/

exp lasers/

exp endoscopy gastrointestinal/

electrocoagulat$.tw.

(therm$ adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(heater adj5 probe).tw.

laser$.tw.

endoclip$.tw.

hemoclip$.tw.

(monopolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(multipolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

(bipolar adj5 coagulat$).tw.

exp sclerosing solutions/

sclerosant$.tw.

polidocanol.tw.

exp polyethylene glycols/

(endoscopic adj3 inject$).tw.

thrombin.tw.

fibrin glue.tw.