Abstract

Background:

Although type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) disproportionately affects Filipino Americans, they have not received much attention in the literature. Focusing on how Filipino Americans’ social and cultural contextual experiences affect their self-management is critical. This study examined T2DM self-management among Filipino Americans by describing their sociocultural experiences, strategies, and significance of self-management.

Method:

An interpretive descriptive qualitative design was used. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. The study followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.

Results:

Filipino Americans (n = 19) with T2DM were interviewed. Three themes emerged: (a) cultural paradox of being Filipino American, (b) movement from invisibility to ownership of T2DM, and (c) definition of successful management of T2DM.

Conclusion:

Results contribute to a greater understanding of Filipino Americans’ T2DM self-management experiences. Implications include the provision of culturally congruent health care, being aware of Filipino Americans’ sociocultural experiences, and involvement of family/community.

Keywords: Filipino Americans, decolonization of health, type 2 diabetes, health equity, colonialism

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) disproportionately affects minoritized groups in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). For instance, Black or African Americans are twice as likely to have diabetes and two to four times as likely to experience diabetes complications, such as kidney failure, amputation, and blindness, compared with non-Hispanic Whites (Chlebowy et al., 2018). For Asian Americans, diabetes is the fifth leading cause of death.

Over four million Filipino Americans (FilAms) live in the United States, constituting the third largest Asian-origin group in the country (Budiman & Ruiz, 2021). FilAms experience high rates of T2DM, with 10% prevalence rate, exceeding that of Chinese Americans (5.6%) and other Asian Americans (9.9%; CDC, 2020). The prevalence rate is even higher at 31% among FilAms between the ages of 65 and 74 years (Araneta, 2019). A greater proportion of FilAms are obese or overweight, have hypertension, and are more likely to delay their medication intake than other Asian Americans or Whites (Adia et al., 2020). Evidence shows that self-management is a critical component of disease management to improve an individual’s quality of life and clinical outcomes (Grey et al., 2015; Powers et al., 2015).

Sociocultural Experiences of FilAms

Social determinants of health (SDOH), including economic stability, neighborhood quality, and the built environment (e.g., buildings, roads, public services, and parks), significantly impact health and well-being (CDC, 2018). Missing from these discussions, however, is the intersection of SDOH and sociocultural factors and how these factors impact diabetes self-management. These sociocultural experiences pertain to FilAms’ culture, history, and social conditions that shape their behavior, thought processes, and emotions in self-managing their T2DM. Their everyday life, such as work, family, health behavior, and lifestyle, their living conditions, such as economy and social standing, and their environment are important facets in managing T2DM. However, other social and cultural experiences (e.g., values and beliefs) are often overlooked in T2DM management discourse. Family and community networks, relationship with food, and history of colonialism are all examples of FilAm values, beliefs, and practices that may influence how they manage T2DM.

Family and Community Networks

Filipino/FilAm families are built on strong cultural values that reflect kinship, cooperation, mutual support, and belonging, where members depend on one another for emotional, psychological, and financial support (Agbayani-Siewert, 1994). Extending these values in disease management, family members often provide instrumental, social, and emotional support. The Filipino values of kapwa (togetherness) and bayanihan (community) emphasize the importance of interconnectedness, family, and support. Kapwa relates to the importance of relationships and community (Tolentino et al., 2023). It is seen as strengthening and preserving relationships and is deeply ingrained in Filipino culture. Bayanihan is a Filipino tradition that promotes the ethos of shared work as a community to achieve a common goal and influence change. Kapwa and bayanihan are related to the collectivistic nature of Filipinos. These values can be crucial in T2DM management, as self-management often occurs within the social or family environment.

Relationship With Food

Food is deeply intertwined with Filipino culture, reflecting community values, generosity, tradition, and emotional connections (Taculao, 2021). It expresses cultural identity and hospitality; food strengthens community bonds and creates social connections. Traditional cooking techniques have been passed down through generations to preserve cultural heritage and maintain cultural pride. Food also serves as comfort and nostalgia, evoking memories of home and childhood. Traditional foods, often high in carbohydrates and fat (e.g., white rice and pork dishes), carry emotional significance and are cherished as sources of comfort and familiarity. Given that diet is a critical component of self-management, FilAms’ relationship with food is critical in understanding diabetes management in this community.

Colonialism

Another sociocultural concept often missed in T2DM research is the relationship between colonialism and health. The Philippines was subjugated by foreign governments such as Spain and the United States for more than 380 years (Robles, 2017), generating a lasting impact on the psyche of Filipinos. The Americanized Golden Legend (e.g., Americans considered liberators and heroes) is one example of the psychological impact of colonialism.

As a result of centuries of colonialism, a type of internalized racism known as colonial mentality is prevalent among Filipinos/FilAms (David & Okazaki, 2006). Colonial mentality is characterized by a belief in cultural inferiority, uncritical rejection of anything Filipino, and a preference for anything American (David, 2013). For instance, the penchant for using English as a sign of intelligence, the assumption that other cultures are of inferior status or intellect, and the American idealizing messages are contemporary experiences of FilAms entrenched in colonial mentality (David, 2013). The psychological consequence of colonial mentality influences FilAm’s identity, which can lead to the loss of the Filipino community (kapwa or bayanihan), marginalization of oneself or others, and reinforcement of negative attitudes toward own culture (David, 2013). Given the complex historical ties of the Philippines to the United States, addressing and evaluating the ongoing effects of colonization, institutional oppression, and marginalization is needed, as these greatly influence FilAm’s health (Sabado-Liwag et al., 2022).

FilAms and T2DM

While FilAms have one of the highest rates of T2DM among Asian Americans (Araneta, 2019; CDC, 2020), few studies have explored the experience of FilAms with T2DM (Araneta, 2019; Bender et al., 2018; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2017; Tolentino et al., 2022). Historically, health has often been regarded through a colonial lens, suggesting their behaviors are non-compliant and inferior (Dawson, 2018). This colonial lens, combined with a biomedical focus, has promoted inaccurate views about the health risks of marginalized groups such as FilAms (Dawson, 2018). Traditional socioeconomic health predictors (such as English proficiency, social position, education, and occupation) may not adequately reflect risk factors associated with FilAms’ health (Sabado-Liwag et al., 2022). Therefore, relying on these traditional risk factors without considering historical contextual experiences contributes to ongoing health disparities of FilAms (Sabado-Liwag et al., 2022).

A systematic review of behavioral programs for T2DM found that culturally tailored programs for minoritized groups can be beneficial in improving glycemic control (Pillay et al., 2015). However, many T2DM self-management studies failed to address the specific needs of FilAms, compounding the health disparities they experience. Previous research on diabetes in FilAms have explored how mobile health self-management tools are perceived (Bender et al., 2018; Maglalang et al., 2017), lifestyle risks associated with chronic diseases (Bayog & Waters, 2017), or health attitudes and factors of unsuccessful management of T2DM (Finucane & McMullen, 2008; Ghimire et al., 2018). In a longitudinal study by Araneta (2019) focusing on the health of Filipino Americans, health outcomes, including T2DM, were examined, revealing risk factors such as excessive visceral fat, insufficient sleep, and persistent social disadvantage. However, to our knowledge, no qualitative study has explored the sociocultural-historical factors that influence the management of T2DM among FilAms.

Conceptual Model

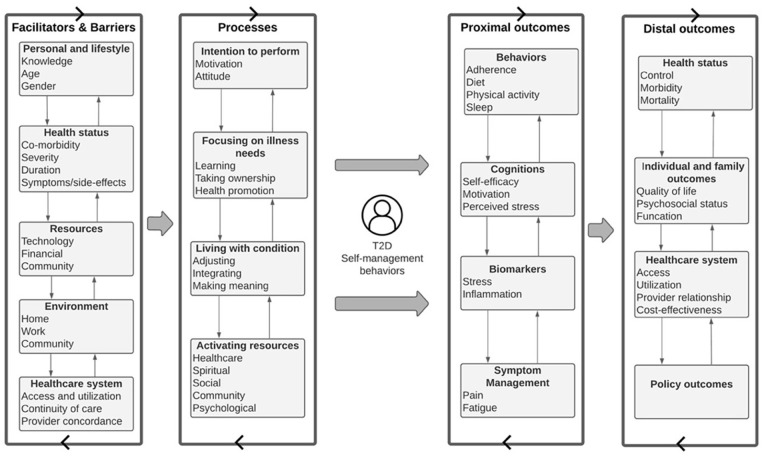

To guide this study, Grey et al.’s (2015) revised self- and family-management framework was used (see Figure 1). This framework was used as it outlines different facilitators and barriers to self-management, including personal/lifestyle (knowledge, beliefs, motivations, and life patterns), resources (financial and community), environment (home, work, and community), and system factors (health care access and provider relationship) associated with self-management (Grey et al., 2015). It also identifies self-management processes focusing on illness needs, resource activation, and living with one’s condition (e.g., adjusting, integrating, and making meaning). Concepts from Schulz et al.’s (2002) Fundamental Determinants of Racial Disparities Theory were also used to situate the discussion of the study results. This theory emphasizes different macrosocial factors and processes that impact the health and well-being of individuals. These concepts include historical conditions, economic structures, political order, social and cultural institutions, and ideologies (e.g., racism). These models served as a framework for the study grounding the work on various sociocultural elements of managing T2DM.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model.

Note. Grey et al.’s (2015) revised self- and family-management conceptual framework was used. Schulz et al.’s (2002) Fundamental Determinants of Racial Disparities Theory was used to situate the discussion of the study (not pictured).

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to examine T2DM self-management among FilAms by describing their sociocultural experiences (e.g., culture, history, and traditions), components, strategies, and significance of self-management of T2DM. The research question was “When managing their type 2 diabetes, how do social and cultural factors such as environment, values, traditions, social network, meaning of food, and stigma affect Filipino Americans’ self-management behaviors and success”?

Methods

Design

An interpretive description, noncategorical qualitative approach (Thorne et al., 1997), was used to explore sociocultural experiences that contributed to participants’ T2DM self-management. Interpretive description allows the researcher to understand the multidimensional and dynamic properties of being a FilAm and allows for findings and interpretations that are culturally anchored in daily diabetes management. This study has been reported following the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist to facilitate transparency of the research process.

Participant Selection

Sampling and Method of Approach

FilAms or Filipinos living in the United States were recruited using purposive sampling by posting the recruitment flyer on social media (i.e., Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter). Philippine Nurses Association of America (PNAA), which shared our call for participants on their social media accounts, endorsed the study.

Sample Size

The final sample size was determined using information power principles (Malterud et al., 2016). Specifically, interviews continued until we could develop an argument with a reasonable basis on which to draw preliminary conclusions based on the study’s aim. Thorne (2020) notes that we reach information power when new ways of thinking about a phenomenon become available.

Data Collection

Data were collected on individual, virtual semi-structured interviews ranging from 30 to 80 min from March to August 2020. Interviews were conducted by both team members (DAT and MEB). Only the participant and the interviewer were present during the interview. All interviews were audio-recorded, conducted in English, and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. Respondents also completed a brief demographic questionnaire. No repeat interviews were carried out. All participants were assigned a code number, and identifying information was redacted in the transcriptions, which were reviewed for anonymity. Participants continued to be recruited until information power was achieved. Participants received monetary compensation for their time and participation. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction.

The interview guide (see Supplementary File) was informed from the literature review and grounded in Grey et al.’s (2015) revised self- and family-management framework. Important factors related to neighborhood, technology experience, knowledge, attitude, beliefs, the definition of successful management of T2DM, and lessons learned were included in the interview guide.

Data Processing and Analysis

Data coding was completed through an iterative team approach. Both members independently started with eclectic coding, the open-ended process of deriving codes from first-impression phrases in four transcripts (Saldaña, 2016). The team met to discuss the emergent codes and collectively developed a working codebook. The codebook was tested on two transcripts, and the codebook was revised to capture the participant experience. The team met after the initial testing and revised the codebook to enhance the trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Coded portions were examined as a team to refine codebook definitions. The team subsequently assigned the coded data to categories and then developed the themes, drawing on the Grey et al. (2015) framework and Schulz et al.’s (2002) Fundamental Determinants of Racial Disparities Theory. NVivo 12 (QSR International, Doncaster, Victoria, Australia) was used to support coding and thematic data analysis. Participants did not provide feedback on the findings.

Trustworthiness of Data

Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) criteria of credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability were used to ensure the trustworthiness of the data in this study. Through the use of two investigators and a variety of participant views throughout the data collection process, the credibility of the data was ensured. Dependability was assured by rigorous data collection and analysis methods. Confirmability was established through unpacking and confronting personal biases through bracketing. One of the authors is of Filipino ancestry and male; their viewpoints and experiences may have influenced how the research was done, and the data were evaluated. Both authors brought their perspectives (including being a nurse [DAT] and a sociologist [MEB]) and experiences to the study to minimize biases and were actively aware of this to avoid influencing the results and conclusions.

In addition, the authors took advantage of an audit trail using an explicit coding schema that defined codes and patterns found during the data analysis. The team actively engaged in critical self-reflection on any potential biases and predispositions we may have brought to the study using reflexivity. The authors tried to moderate their biases and grew more self-aware as a result of reflexivity.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the University of Michigan’s institutional review board (HUM# 00194036). Participants consented to using the online survey prior to the start of the interview. Consent included permission for the audio recording of their interviews.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Table 1 describes the characteristics of participants in this study. A total of 37 participants completed the Qualtrics survey. After 19 interviews, information power was achieved. Most identified as female (69%) and 5% as non-binary. The mean age was 57.3 years (SD = 13.8). Over 68% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree. Well over 70% resided in California, 90% lived in the Philippines before moving to the United States, and 53% earned more than $60,000 yearly. About 69% of the participants reported having other chronic conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol, arthritis, gout, and sleep apnea. All participants reported having health insurance, a primary care provider, and no hospitalizations in the previous year.

Table 1.

Participant Sociodemographic Characteristics (N = 19).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (M = 59, SD = 5) | |

| 30–40 | 1 (5.2) |

| 41–50 | 3 (15.8) |

| 51–60 | 5 (26.3) |

| 61–70 | 5 (26.3) |

| >71 | 3 (15.8) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 14 (73.7) |

| Male | 4 (21.1) |

| Non-binary | 1 (5.2) |

| Education | |

| Some college | 2 (10.5) |

| Associate | 3 (15.8) |

| Bachelor’s | 6 (31.6) |

| Master’s | 6 (31.6) |

| Doctoral | 1 (5.2) |

| Birthplace | |

| Philippines | 18 (94.8) |

| United States | 1 (5.2) |

| Income (annual) | |

| <$30K | 2 (10.5) |

| 31–60K | 3 (15.8) |

| 61K–100K | 5 (26.3) |

| >100K | 7 (36.8) |

| Location | |

| California | 14 (73.7) |

| Outside California | 4 (21.1) |

| Last HbA1c | |

| <7% | 10 (52.7) |

| 7–8% | 6 (31.6) |

| >8% | 3 (15.8) |

| Has insurance | 19 (100) |

| Has PCP | 19 (100) |

| Years with diabetes (M = 8 years) | |

| 1–10 | 12 (63.2) |

| 11–20 | 5 (26.3) |

| >20 | 1 (5.2) |

| No. of hospitalizations in the last year | 0 (0) |

| Considers oneself as religious/spiritual | 16 (84.2) |

Note. PCP = Primary Care Provider.

Themes

Table 2 summarizes the three themes that emerged from our analysis: (a) the cultural paradox of being FilAm, (b) the movement from invisibility to ownership of T2DM, and (c) the definition of successful management of T2DM. There were also several subthemes within each theme.

Table 2.

Themes and Subthemes With Exemplary Quotes.

| Theme 1: Cultural paradox of being Filipino American The cultural tension of being Filipino and American creates a sense of unbelonging and friction in diabetes self-management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtheme | Definition | Participant | Exemplary |

| 1.1. Appreciating Filipino culture and spaces: Bayanihan and social environment as social capital to manage T2DM | The appreciation of culture and social spaces through collective support from family, friends, or coworkers (“bayanihan”). These spaces are positive catalyst to the management of their condition. | P5 | But living here, in our neighborhood, people are health-conscious. For me, it doesn’t really impact me that much because I know what’s going on. My family’s supportive with it. Even my siblings are, like, you know, can you do it without rice, that challenge and stuff? Well, eventually, I was the one challenging them, too, to change their diet. So, as I’ve said, we’re not buying rice every half a week. |

| P5 | Well, yeah. And my wife has a big role in—she is a nurse, too, and she knows, the first year I was sick, she tried her best to modify our diet [laughter] like, 50 percent veggies, and so I’ve almost got to the point of being a vegan [laughter] . . .. She was the most instrumental in the support, because my—our kids, they grew up here, so there’s not much change in that one . . .. It’s just that dynamic that—my wife is the one who supported me the most with that one. | ||

| P9 | Our neighborhood, I like it very much. Like this morning at 8:00 I already did my exercise. I feel safe going around here because it’s a-a safe neighborhood. | ||

| P17 | Very helpful—that support system. My daughter is the one who checks on me. When she knows I have a doctor’s appointment, she’ll say, “So what was your A1C?” or “What was your glucose?” ‘What’s your cholesterol?’ So, there’s that little voice there | ||

| 1.2. Propagation of a belief in the inferiority of being Filipino and its food: “Our culture is a punishment.” | An internalization of the belief that anything Filipino (including its food) is a barrier to optimized self-management behaviors | P1 | Okay. Filipino, as I am, we’re into food. I think much of the behavior of not wanting to be particular about what you eat—I’m, first of all, I’m Filipino. We love grease. We love starch. We love almost everything that’s not- that’s actually prohibited. I don’t think I can do that one. It’s probably because as Filpinos, as I have said, we don’t pay particular attention to, you know, what is currently happening to us unless we go to the hospital and really get sick. |

| P4 | Just remember our culture. We can’t say no. We don’t question authorities. We just listen and believe what they say. So it makes a big difference . . . My A1C, at the time, was 13. I’m 6.7, now, with the pump. So I know, if I stop eating Filipino food, I will be at five. Right? But, you know, [sighs] it’s like it’s asking you to give away your first born. | ||

| P12 | Yeah, our culture is a punishment because I’m so used to that. I’m already 65 right now. Okay, the food, regarding about the food. We do have a lot of starch in our food— a lot of calories—a lot of calories. we do have a lot of process meat, even the fish. | ||

| P15 | So there’s a lot of, you know, Filipino cultural and attitudes that I still have. I know how to speak Tagalog and all that . . .. In some ways, I have adopted a lot of the Western thinking, you know, and my husband is not a Filipino, so in a lot of ways, I have adopted some of his . . . how we manage things here in the US, like preparing for the future and checking or studying what’s your situation and choosing the best option for you, you know? | ||

| Theme 2: Movement from invisibility to ownership of type 2 diabetes This theme describes that despite participants feeling invisible within the diabetes/self-management space, they adjusted to living with their condition by owning their condition facilitated by learning and acceptance. | |||

| Subtheme | Definition | Participant | Exemplary |

| 2.1. Being invisible | The expression of invisibility in the diabetes/self-management space due to lack of Filipino-centric or tailored interventions | P17 | As Filipinos, most of the education out there is geared for the American culture, not—you know, your diabetes instructor doesn’t talk about, Filipino specific. So how do we, as a Filipino group, reach out to our kababayans [Filipino people] to help with that education and compliance, for that matter? |

| P19 | I think that they should just involve everybody. I just feel like we are being left out. They have all kinds of publicized activities for Blacks, for Chinese, but, if they say Asian Americans, they don’t even consider us Asians. And [laughter] it’s funny because I was talking to some person, and they— “Oh, is the Philippines in Asia?” I said, “Yeah. Didn’t you learn that in school?” So, when they say Asian Americans, they normally just look at the Chinese or East Asians or Japanese, Korean. They forget that we are Asians too. So, when there’s an activity for Asian Americans, I don’t see no Filipino representation. | ||

| 2.2. Ownership through learning | Participants emphasized that knowledge accumulation about diabetes is essential in illness ownership. Understanding how to eat healthier, adopting various forms of physical activities, attending a diabetes class, and obtaining information via various modalities were all examples of knowledge-accumulation opportunities that the participants shared. Some discussed how diabetes is a lifelong process of trial-and-error learning | P11 | It’s just hard. That’s like talking to my diabetic pharmacist—he’s like, he doesn’t know what to tell me. But every time I call him it’s different. It’s something different. I’m with <health system>, and I know <health system website> or has information and they have classes as far as resources. It’s like you can read all you want about diets and exercise, but if you’re just reading and not doing it, it’s just—it doesn’t help. |

| P12 | I got confused because of what the doctor is saying and the dietician is saying. I’m going to go to the dietician and take all the knowledge that I can get, and then once I’m over [with] the doctor, doctor says, “No, you should not be.” So, a real big conflict | ||

| P13 | As much as education I get from <health system> as well. It says just-just the size of your palm [rice portion]. I said, “Don’t worry about it, <health system>.” I try not to touch it ‘cause I think in my old age—I said I cannot even digest my food. | ||

| P18 | I had to go to classes, and that’s pretty much where I learned all of the carb counting, the exchanges and things like that. I’ve learned to count carbs. If I can count my carbs, I’m actually good. If I don’t pay attention, that’s when I know. I’ll go, “Okay. my sugar is gonna be up again.” I’ve learned what my sugars are. You know, the fried foods, I think, is the worst, um, because that— lingers. If I eat sweets, I can just do a little exercise, and I’ll be fine. | ||

| Theme 2: Movement from invisibility to ownership of type 2 diabetes This theme describes that despite participants feeling invisible within the diabetes/self-management space, they adjusted to living with their condition by owning their condition facilitated by learning and acceptance. | |||

| Subtheme | Definition | Participant | Exemplary |

| 2.3. Ownership through acceptance | For many people, control over their illness moved through phases of denial to acceptance. Some started with denial, but ultimately ended with accepting their illness. many participants started to take ownership of their illness | P2 | Yeah. Like, but I feel like I’m doing short steps, and then I’m taking 10 big steps backwards sometimes. And I can’t always have reasons for everything. ’Cause that’s how I feel. I feel like I have reasons for everything. |

| P3 | To tell you the truth, since I retired, there’s really a big difference. When I wake up in the morning, my sugar, I’m so happy then. When you wake up in the morning, I’m so happy that, like, below 160. You know? And then I get my breakfast, and then I do again. But then, since I retired, I’m so happy—that it’s going down. | ||

| P5 | Just accept the fact that if you pass that 6 number in A1C, it’s time to change something. Just have to accept that, you know, you’re going there. And I have a lot of friends who are like that too. Like, I shared with them what I did, and hopefully they can follow suit, but acceptance and diet modification—that’s the big part. | ||

| P8 | I will do what I believe is right to maintain, to this date I feel that diabetes is not put a dent on my health . . . As earlier we talk about that life is not measured by how long you live, but how well you lived. If by doing it, they’re happy, and maybe they meet their habit, and I don’t think there is any harm. But that’s also my attitude, and people who are diabetic, and does it well, you’re the master of your own soul, your health. Do what you think is—if you’re happy that way, go ahead. | ||

| Theme 3: Definition of successful management of T2DM This theme refers to how the participants defined successful management of T2DM and how that definition is determined by complex mechanisms, including the internalized trauma of witnessing family members suffer from diabetes complications. This trauma led the participants to adjust, integrate, make meaning out of the everydayness of T2DM, and manage their condition for the sake of their family. | |||

| Subtheme | Definition | Participant | Exemplary |

| 3.1. Avoiding diabetes complications “Watching my mom go through it” | Participants who had family members with T2DM witnessed firsthand how they suffered from complications of the illness. Consequently, many were worried that they would not be able to control their own condition. People were driven to “follow the rules” because they were terrified of complications such as dialysis, daily insulin use, amputation, or other body-related impairments | P3 | Later on, I realized I have to take care of myself because you think about all the complications in your family. It’s my family first. So, I have to take care of myself so that they’re not going to encounter more problem in the future. |

| P11 | Fear of going on dialysis because my mom was on it for 11 years. And she was on—she wasn’t on hemo. She was just through the catheter so, just a fear. You know what dialysis does. She was going four days a week, four hours a day. And so that’s always in the back of my mind. And it’s serious, you know? Just by watching my mom go through 11 years of it and my aunts and uncles, you know, and having them get amputated limbs. I mean, just seeing them go from healthy, energized to the opposite. You don’t want that. And it should scare me. It should, you know, so that I be more better about it. | ||

| P14 | Refraining from going to hospitals, it’s hard. Most important is the diet. Really diet is a very important factor than exercise, and positive attitude—towards, management of illness and to really emphasize that if you don’t manage it then it affects the vital organs of your body. | ||

| P19 | And I was working hard not to get diabetes because it’s just we have members of the family that was very affected by it, kidneys and everything. | ||

| 3.2. “It’s not a death sentence” | An optimistic view of living with type 2 diabetes, with a positive outlook of not viewing it as a terminal disease. It’s a process of acknowledging and understanding their condition in the path toward successful management. | P4 | So you acknowledge that you have it. You explore what’s out there and try to understand that. I want better control of my situation. So understanding the medication and what’s out there and what works. |

| P8 | it’s not a death sentence. I’m going assure [someone with type 2 diabetes] that let’s say I’m the doctor, “Oh, you have type two diabetes, but don’t get worried. It’s not that a death sentence. It can be managed. It can be cured.” We have to assure that having diabetes is not the end of the world. You know, it’s just a condition of health that can be corrected, and can be cured, especially type two diabetes. My feeling is that food is something to do with diabetes | ||

| P14 | My view on that is for as long as you can control your sugar levels probably by 100 minimum because I have never experienced going to 100. It has always been 107, 109, 113, 123 so I hope that by joining this research group I could be helped. | ||

| 3.3. “My family is my big motivation” | Family is a significant motivator to many participants to being successful in their self-management. | P4 | Me and my wife, we’re in the process of having a baby. I think that’s enough reason for me to change my diet. |

| P8 | The first consideration is life. I want to accompany [grandchild] to Harvard when he goes to college. Then honestly, I want to live longer. Life is so nice, so full of wonderful things. But one minute that you can live with additional one minute, or one day, is very good. Life, that’s my motivation. But I do not believe that life is measured by how long you live. No, it’s how well you live. Even if you live 100 years, you are diabetic, would not walk, and could not see, that’s not also good. | ||

| P14 | My family is my big motivation. I have [kids and grandchildren]. I have them and it motivates me to take care of myself because I’d like to see all of them. I need to stay with them for a longer time. . . Yeah, that’s why I would like to become more healthy so I can see them all again. And my family is my life. | ||

Note. T2DM = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Theme 1: The Cultural Paradox of Being FilAm

As being Filipino and American creates a sense of unbelonging in both cultures, FilAms try to blend both cultures into their identity. This blending of cultures emerged as a paradox because their cultural experiences of being FilAm created friction in diabetes self-management, specifically, trying to reconcile Filipino versus Western or American culture and practices. Many appreciated the sense of community (bayanihan) among FilAms as a support in their diabetes self-management, but at the same time were conflicted maintaining Filipino practices as they felt that these practices (such as eating traditional Filipino food, the never-ending family gatherings with the pressures of eating, being teased of being “healthy”) contributed to suboptimal diabetes management.

Appreciating Filipino Culture and Spaces: Bayanihan and Social Environment as Social Capital to Manage T2DM

The spirit of bayanihan, through collective social support provided by family members, friends, or coworkers, was one of the key facilitators to the successful management of T2DM reported by study participants. Individuals benefited from members of their social communities acting as advocates, caregivers, counselors, and coaches. As one participant put it, self-management is a “team effort,” with her daughter playing a pivotal role. She elaborates:

Very helpful—that support system. My daughter is the one who checks on me. When she knows I have a doctor’s appointment, she’ll say, “So what was your A1C?” or “What was your glucose?” “What’s your cholesterol?” So, there’s that little voice there (P17, 69 years old).

Many individuals valued their social environment (e.g., place of work or living) as they lived or worked in spatially concentrated communities that reinforced family ties and cultural identities (i.e., ethnic enclaves). Most of the participants from California had relatively high median earnings and lived in communities with a minor detrimental impact on their ability to manage their condition. Many expressed appreciation for the social space they occupied, in that it helped them manage their T2DM. This was due to their access to services that helped them manage their T2DM. Many participants indicated their neighborhoods were safe, with easy access to shopping, health care services, and parks.

I can drive to my hospital. I can grab my medication, and there’s not a big impact, neighborhood-wise, at all. No impact there (P2, 36 years old).

Propagation of a Belief in the Inferiority of Being Filipino and Its Food: “Our Culture Is a Punishment.”

Despite the advantages of bayanihan and adequate social spaces, a paradox emerged from this study about being FilAm. Many conveyed the burden of consuming Filipino food and being Filipino as barriers to diabetes self-management. Some blamed being Filipino as the cause of their diabetes and felt that it had led them to suboptimal self-management. As one participant explained, being Filipino made them ignore their condition until it was too late, “It’s probably because, as Filipinos, we don’t pay particular attention to what is currently happening to us unless we go to the hospital and really get sick” (P1, 42 years old).

Others pointed out that they assimilated to a Western lifestyle, particularly regarding their nutritional habits, as they saw Filipino practices (i.e., food) as inferior. One participant described their culture as a punishment because of their perception of Filipino foods’ lack of nutritional content. He said that this tension between appreciation and denunciation of “being Filipino” has created a paradox of cultural friction and safety.

Theme 2: Movement From Invisibility to Ownership of T2DM

Many participants shared they often do not see many Filipino-specific diabetes education and support programs in the United States. However, despite this limitation, many adjusted to living with T2DM through learning and acceptance, as they were motivated to increase self-control and improve the management of their T2DM by owning their condition.

Being Invisible

Participants highlighted the importance of diabetes education in self-management. However, many expressed feeling invisible in many diabetes education and support programs. One participant shared her feelings about being omitted and not considered Asian American.

I just feel we are being left out. They have all kinds of publicized activities for Black people, for Chinese, but if they say Asian Americans, they don’t even consider us Asians (P19, 60 years old).

In addition, participants highlighted the lack of individualized instructions for Filipinos, which was a hurdle when it came to learning more about diabetes. Although many felt they were not seen, they stressed the need to start with oneself when learning about diabetes.

Ownership Through Learning

Participants emphasized that knowledge accumulation about diabetes is essential in illness ownership. Understanding how to eat healthier, adopting various forms of physical activities, attending a diabetes class, and obtaining information via various modalities were all knowledge-accumulation opportunities that the participants shared. Some discussed how diabetes is a lifelong process of trial-and-error learning. One participant said,

You have that episode wherein I check my blood sugar because I ate a lot. Then I must cut down on what I eat the following day because my sugar was a little bit high. It creates that consistency—I can see that one right now. I have significantly changed my starch intake (P1, 42 years old).

Others noted the difficulty of trusting information from specific sources, notably the internet (e.g., Facebook, Google searches, WebMD, TED Talks, and health care system websites). A few questioned their primary care provider’s information because it only sometimes matched other sources (e.g., the internet or other health care providers). Nonetheless, many acknowledged that a lack of knowledge hurts their chances of being healthy and that learning is crucial to owning their condition and ultimately managing T2DM successfully.

Ownership Through Acceptance

For many people, control over their illness moved from denial to acceptance. The initial diagnosis was a shock for some participants, and they did not take it seriously. As one participant said after being diagnosed with T2DM: “I didn’t consider it really seriously. . . . Because of my personal issue, I didn’t really care” (P4, 55 years old). Regardless of how they responded to their initial diagnosis, many participants eventually took ownership of their illness.

Many noted numerous setbacks and challenges with self-management, although some appreciated the discovery process. “It has to start from me,” remarked a participant (P6, 44 years old). A person summed up the process of ownership through acceptance by citing a popular Filipino proverb, “You may bring the carabao to the river, but you can’t force the carabao to drink” (P12, 65 years old). This emphasizes that owning one’s illness and taking healthful actions is a form of empowerment critical to the successful management of T2DM.

Theme 3: Definition of Successful Management of T2DM

This theme refers to how the participants defined successful management of T2DM and how that definition is determined by complex mechanisms, such as the intergenerational witnessing of family members suffering from diabetes complications. This intergenerational witnessing led participants to adjust, integrate, make meaning out of the everydayness of T2DM, and manage their condition for the sake of their families.

Avoiding Diabetes Complications: “Watching My Mom Go Through It.”

Participants who had family members with T2DM witnessed firsthand how they suffered from complications of the illness. Consequently, many worried they would be unable to control their condition. Participants were driven to “follow the rules” because they were terrified of diabetes complications such as dialysis, daily insulin use, amputation, or other body-related impairments.

One participant shared her experience of witnessing family members go from being healthy to seeing them get amputations.

It’s serious. Just by watching my mom go through 11 years of it and my aunts and uncles and having them get amputated limbs. Just seeing them from healthy, energized to the opposite. You don’t want that. And it should scare me. So that I be better about it (P11, 51 years old).

The witnessing of intergenerational uncontrolled diabetes over time has imposed distressing experiences for FilAms and fear for their fates; these concerns motivated many to engage in optimal self-care behaviors. To many of the participants we interviewed, the ability to avoid the same complications their family members experienced would mean they managed their diabetes successfully.

“It Is Not a Death Sentence.”

Although some mentioned feelings of exhaustion with dealing with self-management, many shared that living with diabetes is manageable and “it is not a death sentence” (P8, 82 years old). They described going through denial, acceptance, adjustment, and integration phases. Many went on to accept their diagnosis and found ways for living with T2DM. They shared that to be successful is not to let T2DM take control over their lives. One said, “I’m not afraid of diabetes. Diabetes is just one of them. I’m ready to battle diabetes” (P8, 82 years old).

Participants said they benefited from living in moderation, advocating for their health, being curious about new treatments or technologies, maintaining a goal, and taking care of themselves by taking control of living with T2DM. One participant said, “There’s no secret actually [to self-management]. Eat less and do more exercise” (P6, 44 years old).

Although many acknowledged the struggles of living with T2DM, they found solace in the support they received from family members and the power to take charge of their illness by adjusting to, integrating, and making meaning of living with T2DM.

“My Family Is My Big Motivation.”

For many participants, the goal of successfully managing their T2DM was more than illness control, such as having stable blood sugar levels. Although many acknowledged that optimal physiological outcomes are vital, many also talked about success as maintaining their health so they can do more with their families. One participant said, “My family is my life” (P14, 70 years old).

For many participants, success is more than just the conventional biomedical outcomes of physiological success. Their view of success is informed by witnessing intergenerational diabetes complications, leading them to define success as being free of these complications. In addition, it is about the acknowledgment that diabetes is not necessarily a death sentence and that their family is a significant motivator for them to succeed in managing their T2DM.

Discussion

This study described the cultural paradox, invisibility, ownership, and definition of successful management of T2DM among Filipino Americans. It builds on Grey’s Self- and Family-Management Theory and Schulz et al.’s (2002) Fundamental Determinants of Racial Disparities Theory by highlighting the sociocultural experiences (e.g., culture, history, traditions, economic structures, and social institutions), components, strategies, and significance of self-management among Filipino Americans.

Colonial Mentality and Self-Management

In this study, participants exhibited a colonial mentality mind-set that may have impacted their self-management of T2DM, including the feeling of being inferior, intergenerational witnessing of uncontrolled diabetes, and being invisible. The vilification of the Filipino culture—the belief that anything American or Western is superior or that there needs to be a dichotomous choice between Western and Filipino traditions—reflects experiences of colonial mentality. Colonial mentality is a type of internalized racism marked by a perception of ethnic or cultural inferiority or inadequacy (David, 2013; David & Nadal, 2013). The effects of colonialism on psychological health have been studied before on various ethnic groups (Chandanabhumma & Narasimhan, 2020; Decena, 2014; Eni et al., 2021; Gillson et al., 2022). Not surprisingly, a colonialist view is observed in many FilAms (David, 2013), including in their food practices (Orquiza, 2020). Many participants equated the Filipino culture as a challenge, with some even associating being Filipino with having diabetes and believing that their traditions and practices posed barriers to successful diabetes self-management. Milo et al. (2021) recommended in their study on patient activation and glycemic control among FilAms that understanding the role of culture and diabetes self-management requires cultural flexibility and finding a culturally acceptable middle ground to improve engagement.

Many participants also experienced watching their loved ones experience life-altering complications of T2DM, including amputations and dialysis treatments. We argue that this overwhelming experience of watching loved ones suffer T2DM complicates self-management. With the persistently high rates of T2DM among FilAms, particularly among Filipino men (15.8%; Araneta, 2019; Choi et al., 2013), compounded by the fact that many FilAms’ family members have T2DM, this constant exposure, we argue, may have led to the normalization of complications and internalization of having diabetes. As little is known about the effects of multiple generations experiencing the same health condition, it is vital to understand this pathway in future research studies.

It was also apparent how FilAms with T2DM felt invisible within the health care system. Many expressed that diabetes education programs and support are not tailored to their cultural needs. Despite FilAm’s status as the second largest Asian American group (Pew Research Center, 2021), they continue to be understudied in diabetes care and research and continue to be the “forgotten Asian American” (Cordova, 1983). The failure to focus on marginalized groups, including FilAms, in the United States has led to underappreciation of the health challenges experienced by these communities, the undermining of their unique diabetes needs, and the often masking of many of their health care needs that, if addressed, could lead to optimal diabetes self-management.

Taking Control

Despite the challenges participants faced, many found success in managing their T2DM through social connections, ownership of the disease, and making meaning of living with T2DM. Traditional Filipino values and cultural norms of togetherness and support networks, such as family environment and day-to-day social interactions, played a significant part in participants’ overall health (Kawachi et al., 2008). The concept of social and community networks—often known as social capital—is an important social determinant of health (Kawachi et al., 2008). Concepts of social capital and support networks are not foreign to FilAms. The Filipino values of Kapwa (translated as togetherness) and bayanihan (translated as community) were evident in this study. Many described their family and friends as a support system and motivators in their daily management of T2DM. Beyond social networks, many participants talked about other resources, for example, information channels for learning, that were essential to managing their T2DM. Many shared the importance of learning through various modalities but noted the challenges with mis/disinformation and miscommunication, sometimes even from their primary care providers. Moreover, although some felt invisible within the health care system, they credited ownership of their diabetes through learning and acceptance as paths to successfully managing their condition.

FilAms are the third largest Asian American subgroup in the United States and have one of the highest prevalence rates of T2DM. Diabetes care should be provided to them in a way that acknowledges and understands their sociocultural experiences. This includes being aware of their cultural background, values, and beliefs and involving their family in their care. Health care organizations should provide training and education on cultural sensitivity. Nurses should collaborate with other health care professionals with cultural competency and FilAm health expertise.

Future Studies and Limitations

Future studies should focus on FilAm’s use of social capital, including social relationships (Kawachi et al., 2008), cultural collectivism (Sabado-Liwag et al., 2022), information intake, and colonial mentality, and how these factors impact the management of T2DM. In addition, as a colonial mentality seems to be apparent among FilAms, bicultural efficacy is an important outcome that needs to be included in FilAm diabetes studies. Although some T2DM studies with FilAms as participants include acculturation measurements (Bender et al., 2017; Inouye et al., 2015), few have included biculturalism as an outcome. Biculturalism involves applying dual modes of sociocultural behaviors and adjusting to different cultural contexts (Chun et al., 2016). Future studies should include a more diverse sample of Filipino Americans (including geographic and income diversity), as those with lower socioeconomic scales or Filipinos living in other parts of the United States may have other challenges.

There were several limitations to this study. Open-ended questions allowed participants to express their views without the researchers’ influence. However, the meanings of their responses were only sometimes evident. One-word comments, for instance, could have been misinterpreted because it took time to ascertain their intended meaning. Although many participants lived in California, the authors provided thick descriptions in the study, making it transferable to other settings. Finally, since the team members were primarily recruited online, those who did not have access to the recruitment materials may have been inadvertently excluded from the study.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that FilAms’ sociocultural history and experiences are essential to their T2DM management. Despite viewing their culture as a punishment, feeling invisible, and experiencing intergenerational witnessing of T2DM, FilAms cited individual, cultural, and social factors to support their optimal management of T2DM. We must continue our awareness about this community and develop and implement culturally relevant interventions focusing on their needs in future studies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tcn-10.1177_10436596231209041 for Filipino Americans’ Social and Cultural Experiences of Type 2 Diabetes Management: Cultural Paradox, Ownership, and Success Definition by Dante Anthony Tolentino and Mary E. Brynes in Journal of Transcultural Nursing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-tcn-10.1177_10436596231209041 for Filipino Americans’ Social and Cultural Experiences of Type 2 Diabetes Management: Cultural Paradox, Ownership, and Success Definition by Dante Anthony Tolentino and Mary E. Brynes in Journal of Transcultural Nursing

Acknowledgments

We thank the Philippine Nurses Association of America for their endorsement of the study. We also thank Kris Langabeer at the UCLA School of Nursing for technical editing, language editing, and proofreading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Tolentino acknowledges funding support from Sigma Theta Tau—Beta Mu Chapter, the School of Nursing and the National Clinician Scholars Program at the University of Michigan at the time of the study.

ORCID iD: Dante Anthony Tolentino  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4026-9031

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4026-9031

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Adia A. C., Nazareno J., Operario D., Ponce N. A. (2020). Health conditions, outcomes, and service access among Filipino, Vietnamese, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Adults in California, 2011-2017. American Journal of Public Health, 110(4), 520–526. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbayani-Siewert P. (1994). Filipino American culture and family: Guidelines for practitioners. Families in Society, 75(7), 429–438. https://doi:10.1177/104438949407500704 [Google Scholar]

- Araneta M. R. (2019). Engaging the ASEAN diaspora: Type 2 diabetes prevalence, pathophysiology, and unique risk factors among Filipino migrants in the United States. Journal of the ASEAN Federation of Endocrine Societies, 34(2), 126–133. 10.15605/jafes.034.02.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayog M. L. G., Waters C. M. (2017). Cardiometabolic risks, lifestyle health behaviors and heart disease in Filipino Americans. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing: Journal of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Nursing of the European Society of Cardiology, 16(6), 522–529. 10.1177/1474515117697886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M. S., Cooper B. A., Flowers E., Ma R., Arai S. (2018). Filipinos Fit and Trim—A feasible and efficacious DPP-based intervention trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, 12, 76–84. 10.1016/j.conctc.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M. S., Cooper B. A., Park L. G., Padash S., Arai S. (2017). A feasible and efficacious mobile-phone based lifestyle intervention for Filipino Americans with type 2 diabetes: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Diabetes, 2(2), e30. 10.2196/diabetes.8156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budiman A., Ruiz N. G. (2021). Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/ [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Social determinants of health: Know what affects health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/index.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Type 2 diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/type2.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Prevalence of diagnosed diabetes. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/diagnosed-diabetes.html

- Chandanabhumma P. P., Narasimhan S. (2020). Towards health equity and social justice: An applied framework of decolonization in health promotion. Health Promotion International, 35(4), 831–840. 10.1093/heapro/daz053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowy D. O., Coty M. B., Fu L., Hines-Martin V. (2018). Comorbid diabetes and depression in African Americans: Implications for the health care provider. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(1), 111–116. 10.1007/s40615-017-0349-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S. E., Liu M., Palaniappan L. P., Wang E. J., Wong N. D. (2013). Gender and ethnic differences in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes among Asian subgroups in California. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 27(5), 429–435. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun K. M., Kwan C. M., Strycker L. A., Chesla C. A. (2016). Acculturation and bicultural efficacy effects on Chinese American immigrants’ diabetes and health management. Journal of Behavior Medicine, 39(5), 896–907. 10.1007/s10865-016-9766-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova F. (1983). Filipinos: Forgotten Asian Americans. Kendall/Hunt Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- David E. J. R. (2013). Brown skin, white minds: Filipino—American postcolonial psychology. Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- David E. J. R., Nadal K. L. (2013). The colonial context of Filipino American immigrants’ psychological experiences. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(3), 298–309. 10.1037/a0032903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David E. J. R., Okazaki S. (2006). Colonial mentality: A review and recommendation for Filipino American psychology. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 12(1), 1–16. 10.1037/1099-9809.12.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson L. C. (2018). Histories, bodies, stories, hungers: The colonial origins of diabetes as a health disparity among Indigenous peoples in Canada [Doctoral dissertation, University of Alberta]. 10.7939/R3BN9XJ7N [DOI]

- Decena A. M. (2014). Identity, colonial mentality, and decolonizing the mind: Exploring narratives and examining mental health implications for Filipino Americans [Master’s thesis, Smith College]. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/769

- Eni R., Phillips-Beck W., Achan G. K., Lavoie J. G., Kinew K. A., Katz A. (2021). Decolonizing health in Canada: A Manitoba first nation perspective. International Journal for Equity in Health, 20(1), 206. 10.1186/s12939-021-01539-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane M. L., McMullen C. K. (2008). Making diabetes self-management education culturally relevant for Filipino Americans in Hawaii. The Diabetes Educator, 34(5), 841–853. 10.1177/0145721708323098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E., Roy A., Chan K. T.-K., Kobayashi K. M. (2017). Diabetes among non-obese Filipino Americans: Findings from a large population-based study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 108(1), e36–e42. 10.17269/cjph.108.5761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire S., Cheong P., Sagadraca L., Chien L.-C., Sy F. S. (2018). A health needs assessment of the Filipino American community in the greater Las Vegas Area. Health Equity, 2(1), 304–312. 10.1089/heq.2018.0042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillson S. L., Hautala D., Sittner K. J., Walls M. (2022). Historical trauma and oppression: Associations with internalizing outcomes among American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. Transcultural Psychiatry, 13634615221079146. Advance online publication. 10.1177/13634615221079146 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Grey M., Schulman-Green D., Knafl K., Reynolds N. R. (2015). A revised self- and family management framework. Nursing Outlook, 63(2), 162–170. 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye J., Li D., Davis J., Arakaki R. (2015). Psychosocial and clinical outcomes of a cognitive behavioral therapy for Asians and Pacific Islanders with type 2 diabetes: A randomized clinical trial. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 74(11), 360–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Subramanian S. V., Kim D. (2008). Social capital and health. In Kawachi I., Subramanian S. V., Kim D. (Eds.), Social capital and health (pp. 1–26). Springer. 10.1007/978-0-387-71311-3_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y. S., Guba E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Maglalang D. D., Yoo G. J., Ursua R. A., Villanueva C., Chesla C. A., Bender M. S. (2017). “I don’t have to explain, people understand”: Acceptability and cultural relevance of a mobile health lifestyle intervention for Filipinos with type 2 diabetes. Ethnicity & Disease, 27(2), 143. 10.18865/ed.27.2.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K., Siersma V. D., Guassora A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R. B., Ramira A., Calero P., Georges J. M., Perez A., Connelly C. D. (2021). Patient activation and glycemic control among Filipino Americans. Health Equity, 5(1), 151–159. 10.1089/heq.2020.0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orquiza R. A. D., Jr. (2020). Taste of control: Food and the Filipino colonial mentality under American rule. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2021). Filipinos in the U.S. fact sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/fact-sheet/asian-americans-filipinos-in-the-u-s/

- Pillay J., Armstrong M. J., Butalia S., Donovan L. E., Sigal R. J., Vandermeer B., Chordiya P., Dhakal S., Hartling L., Nuspl M., Featherstone R., Dryden D. M. (2015). Behavioral programs for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(11), 848–860. 10.7326/M15-1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers M. A., Bardsley J., Cypress M., Duker P., Funnell M. M., Hess Fischl A., Siminerio L., Vivian E. (2015). Diabetes self-management education and support in type 2 diabetes: A joint position statement of the American Diabetes Association, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Diabetes Care, 38(7), 1372–1382. 10.2337/dc15-0730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robles A. C. (2017, October 15). No trust in institutions. D+C: Development and Cooperation. https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/anti-democratic-legacy-spanish-and-us-colonialism-philippines

- Sabado-Liwag M. D., Manalo-Pedro E., Taggueg R., Jr., Bacong A. M., Adia A., Demanarig D., Sumibcay J. R., Valderama-Wallace C., Oronce C. I. A., Bonus R., Ponce N. A. (2022). Addressing the interlocking impact of colonialism and racism on Filipinx/a/o American health inequities. Health Affairs, 41(2), 289–295. 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz A. J., Williams D. R., Israel B. A., Lempert L. B. (2002). Racial and spatial relations as fundamental determinants of health in Detroit. The Milbank Quarterly, 80(4), 677–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taculao P. B. (2021, March 26). Celebrating food, culture, and the Filipino with the Filipino food month. Manila Bulletin. https://mb.com.ph/2021/03/26/celebrating-food-culture-and-the-filipino-with-the-filipino-food-month/

- Thorne S. (2020). Untangling the misleading message around saturation in qualitative nursing studies. Nurse Author & Editor, 30(1), 1–9. 10.1111/j.1750-4910.2020.tb00005.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S., Kirkham S. R., MacDonald-Emes J. (1997). Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing & Health, 20(2), 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino D. A., Ali S., Jang S. Y., Kettaneh C., Smith J. E. (2022). Type 2 diabetes self-management interventions among Asian Americans in the United States: A scoping review. Health Equity, 6(1), 750–766. 10.1089/heq.2021.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolentino D. A., Roca R. P. E., III, Yang J., Itchon J., Byrnes M. E. (2023). Experiences of Filipino Americans with type 2 diabetes during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 45(6), 562–570. 10.1177/01939459231162917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tcn-10.1177_10436596231209041 for Filipino Americans’ Social and Cultural Experiences of Type 2 Diabetes Management: Cultural Paradox, Ownership, and Success Definition by Dante Anthony Tolentino and Mary E. Brynes in Journal of Transcultural Nursing

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-tcn-10.1177_10436596231209041 for Filipino Americans’ Social and Cultural Experiences of Type 2 Diabetes Management: Cultural Paradox, Ownership, and Success Definition by Dante Anthony Tolentino and Mary E. Brynes in Journal of Transcultural Nursing