Abstract

Young adults (YAs), defined as individuals between the ages of 18 and 39 years, experience unique challenges when diagnosed with advanced cancer. Using the social constructivist grounded theory approach, we aimed to develop a theoretical understanding of how YAs live day to day with their diagnosis. A sample of 25 YAs (aged 22–39 years) with advanced cancer from across Canada participated in semi-structured interviews. Findings illustrate that the YAs described day-to-day life as an oscillating experience swinging between two opposing disease outcomes: (1) hoping for a cure and (2) facing the possibility of premature death. Oscillating between these potential outcomes was characterized as living in a liminal space wherein participants were unsure how to live from one day to the next. The participants oscillated at various rates, with different factors influencing the rate of oscillation, including inconsistent and poor messaging from their oncologists or treatment team, progression or regression of their cancer, and changes in their physical functioning and mental health. These findings provide a theoretical framework for designing interventions to help YAs adapt to their circumstance.

Keywords: adolescent and young adults, cancer, grounded theory, psychosocial, oncology, qualitative, rehabilitation, palliative care

Background

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs), defined as individuals aged 15–39 years, face unique and marked challenges when diagnosed with an advanced cancer (Avery et al., 2020a, 2020b; Wiener et al., 2015). AYAs with advanced cancer, defined as a stage 4 or incurable diagnosis of any type of cancer and/or recurrent or metastasized cancer, have an ongoing need for life-sustaining cancer treatments and symptom management (Abdelaal et al., 2021; Figueroa Gray et al., 2018). However, they still face the real prospect of dying at a young age (Burgers et al., 2022a, 2022b; Knox et al., 2017). These individuals are at a life stage typified by seeking autonomy from their parents, developing their own values and identity, focusing on building relationships, embarking on a career, and starting a family of their own (Arnett et al., 2014). Advanced cancer during adolescence and young adulthood disrupts this development (Barakat et al., 2016; Burgers et al., 2022a, 2022b). AYAs with advanced cancer have reported feeling socially isolated from their peers and family, dependent on others, and unable to pursue life goals or achieve developmental milestones (Clark & Fasciano, 2015; Zebrack & Isaacson, 2012). The current literature on supportive care in advanced cancer has not focused on the unique challenges faced by AYAs with advanced cancer, leaving limited evidence or available services to address the challenges of having advanced cancer as an AYA (Berkman et al., 2020; Johnston et al., 2018).

Services involving palliative care, cancer rehabilitation, and psychosocial support are critical components of high-quality supportive cancer care (Alfano et al., 2019; Silver et al., 2015). The integration of these services early in the disease trajectory has shown promise in improving the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer independent of age and cancer type (Mathews et al., 2021; Nottelmann et al., 2021; Teo et al., 2019). However, successful early integration of these services for AYAs lags far behind those seen in paediatric and older age groups (Baird et al., 2019; Lockwood et al., 2021; McGrady et al., 2022), and as a result, less is known about the best model to support the unique needs of this population (Knox et al., 2017; Wiener et al., 2015). In addition, few studies have explored illness experience of these AYAs, which has led to a dearth of knowledge and evidence of how to provide them with appropriate and timely supportive cancer care (Knox et al., 2017; Soanes & Gibson, 2018; Wiener et al., 2015). Specialized supportive and palliative care programs are being developed, but there continues to be a lack of consensus on best practices (Abdelaal et al., 2023; Coburn et al., 2023).

Proportionally, in Canada, AYA patients over the age of 18 are more likely to receive care at adult cancer centre than a paediatric one (Gupta et al., 2016). This study is primarily focused on informing supportive care for AYAs being treated in adult cancer centres. Thus, we focused on young adults (YAs), aged 18–39 years. We aimed to explore the illness experience of YAs receiving care at adult cancer centres and how they navigated their day-to-day life with an advanced-stage cancer diagnosis. Our goal was to create a theoretical rendering of the experience to guide the development of support and integration strategies for this population. The following two research questions drove the development of this theoretical rendering: (1) How do YAs live with and navigate their day-to-day life with an advanced-stage cancer diagnosis? (2) What challenges impact YAs’ ability to live well from one day to the next?

Study Design

We used constructivist grounded theory methodology based on our intention of illuminating the processes by which YAs live and navigate their day-to-day life with an advanced cancer diagnosis. Our goal was to develop a theoretical framework that outlines these processes to guide the development of supportive care programming to support these individuals. Consistent with a social constructivist theoretical positioning, we considered ourselves as researchers who were not passive objective observers but rather active participants in creating meaning (Charmaz, 2014; Creswell, 2014; Denzin & Lincoln, 2005; Mills et al., 2006). Our intent and positioning are aligned with Charmaz’s (2014) constructivist grounded theory methodology and therefore was used as a guide to data collection and analysis. We also adopted the 1980 World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Disability and Health (ICF) model as a conceptual framework to guide data collection and analysis (Levasseur et al., 2007). The ICF model illustrates the dynamic interplay between health conditions, personal factors, and the environment to determine whether disordered function results in participation restrictions (Gilchrist et al., 2009). A disordered function does not always result in participation restrictions. For example, as Gilchrist et al. (2009) illustrated, if a cancer treatment (e.g. chemotherapy) causes a patient to develop unresolved pain and leg weakness, this patient may have a limited ability to move (limitation) and may require long-term use of a leg brace. Limited ability to walk could result in an employment restriction for a firefighter but not for a computer programmer (p. 288). The ICF has been used as a conceptual framework to understand how various illnesses can result in participation restrictions. The ICF has been used as a conceptual framework to explore the impact of a breast cancer (see Pinto et al., 2022), cardiovascular illness (see Lee et al., 2018), stroke (see Perin et al., 2020), and diabetes (see Wildeboer et al., 2022). Using the ICF model as a conceptual framework provided a concise and organized way to explore how advanced cancer (the health condition) impacted how YAs live their life (personal and environmental) and ways they go about living from one day to the next when they encounter participation restrictions because of their diagnosis (Cheville et al., 2017; Bornbaum et al., 2013).

Setting, Recruitment, and Study Participants

Canada is geographically divided into 10 provinces and 3 territories within which comprehensiveness, design, and delivery of cancer control programs vary (Sutcliffe, 2011). Healthcare is publicly funded through the Canada Health Act and is implemented through federal, provincial, and territorial governments. Each province and territory have its own cancer control program that develops policies and provides services specific to a patient’s diagnosis, treatment, and support. Variations exist between cancer control programs, which could impact the experiences and needs of those receiving oncological and supportive care across Canada. To capture this possible variation, we divided Canada into five regions (Figure 1), enabling us to recruit a heterogeneous sample of YAs from different regions to ensure geographic diversity in our sample. We recruited fluent English-speaking YAs between 18 and 39 years of age residing in different regions of Canada diagnosed with advanced-stage cancer. Ethics approval was obtained from the University Health Network (UHN) (CAPCR# 20-5156) and the University of British Columbia/BC Cancer harmonized (#H20-02424) research ethics boards.

Figure 1.

Regions of Canada.

We used convenience, purposeful, and snowball sampling to recruit a heterogeneous sample of YAs across age (18–24; 25–31; 32–39 years of age), gender (men; women), years living with cancer (0–1 year; 1–5 years; 5 years or more), and geographical region. Participants were recruited through our clinician partners at outpatient cancer care clinics at two Canadian tertiary cancer centres (The Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (PM) (Toronto, Canada) and BC Cancer Vancouver (BCCV); from an email distribution list of YAs who partook in a previous YA research project and who expressed interest in participating in future research (Avery et al., 2022); through the distribution of an invitation letter by our community partners; and through other participants who volunteered to forward an invitation letter to potential participants. A broad definition of advanced cancer was used to screen each potential participant for eligibility. We defined advanced cancer as any stage 4 diagnosis of any type of cancer and/or cancer that had metastasized and/or recurred one or more times. The research lead (JA) provided this definition to each potential participant during participant screening and before obtaining informed consent. As data collection evolved, recruitment became more targeted to ensure representation across age, gender, years living with cancer, and regions of Canada.

Our final sample included 25 YA participants (age range 22–39 years). Most were between 30 and 39 years of age (19/25, 76%), were women (19/25, 76%), and resided in the province of Ontario (14/25, 56%) or British Columbia (7/25, 28%) (Table 1). Just under half of the participants (11/25, 44%) had been diagnosed with cancer within a year at the time of their interview, with the remainder living with their advanced cancer between 2 and 5 years (7/25, 28%), for 6–10 years (3/25, 12%), or for over 10 years (4/25, 16%) with 5 (20%) having multiple recurrences and living for periods with no evidence of disease. Breast cancer (7/25, 28%) and sarcoma (6/25, 24%) were the most common primary cancers, with lung (3/25, 12%), Hodgkin’s lymphoma (2/25, 8%), colorectal (2/25, 8%), leukaemia (1/25, 4%), and other types of cancer (4/25, 16%) as the remaining types.

Table 1.

Qualitative Interview Guide.

| Question | Probes |

|---|---|

| What is it like to live with advanced cancer as a young adult? | • When were you diagnosed? What was it like to be diagnosed at that age? |

| How does advanced cancer impact your experience in day-to-day life as a young adult? | • How does your diagnosis impact the things you want to be doing? |

| • Can you elaborate on what causes those difficulties? | |

| What are the different things you are doing to overcome these difficulties? | • How have you attempted to carve out a life for yourself? |

| • What has worked? What hasn’t worked? | |

| • Why have these things worked or not worked? | |

| • What do you wish had worked? Why? | |

| What services and/or supports are you accessing? | • What was it about these supports/services that helped you? What hasn’t helped? |

| • Why have these things worked or not worked? | |

| • What do you wish had worked? Why? | |

| • What type of services/supports would you like to see? Can you elaborate on what these services might look like? | |

| What was the process like when you finished your treatment? | • What were or are some of the physical/psychological/social concerns you are/have faced since you have finished your treatments? |

| • How did the treatment phase affect your relationships with your family/friends/co-workers? Can you speak more about this? | |

| • Can you talk about some of the support you received from family/friends/clinicians around the management of these concerns? | |

| Is there anything else that you would like to add? | • Is there any important issue that we have not talked about and that you would like to share with me? |

Data Collection

We conducted semi-structured, one-on-one interviews as the primary method of data collection. An interview guide was developed (see Table 2) using the ICF and previous literature on YA care to design questions that explore YAs’ efforts to live and cope with advanced cancer, emphasizing the personal and environmental challenges they experience. Questions evolved during data collection to help identify the most relevant themes that described their experience and the processes by which they lived from one day to the next with their illness. For example, after six interviews, descriptions of living in a liminal space had been variously described by all participants, and we identified this as an emerging theme to explore further. Thus, we introduced preliminary descriptions and conceptualizations of this liminal space to subsequent participants and asked how this compared to their experiences. Interviews were conducted by the research lead (JA) virtually using the Microsoft Teams platform. Each participant participated in one interview and completed a demographic form so we could describe the study sample. No follow-up interviews were completed.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics.

| Participant characteristics | Frequency (%) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–24 years old | 1 (4.00%) | 22–39 |

| 25–29 years old | 5 (20.0%) | |

| 30–39 years old | 19 (76.0%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 6 (24.0%) | |

| Female | 19 (76.0%) | |

| Cancer type | ||

| Lung | 3 (12.0%) | |

| Breast | 7 (28.0%) | |

| Sarcoma | 6 (24.0%) | |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 2 (8.00%) | |

| Colorectal | 2 (8.00%) | |

| Leukaemia | 1 (4.00%) | |

| Other | 4 (16.0%) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/life partner | 13 (52.0%) | |

| Single/never married | 9 (36.0%) | |

| Divorce/separated | 2 (8.00%) | |

| Others | 1 (4.00%) | |

| Province of residence | ||

| Ontario | 14 (56.0%) | |

| British Columbia | 7 (28.0%) | |

| Manitoba | 2 (8.00%) | |

| Alberta | 1 (4.00%) | |

| Saskatchewan | 1 (4.00%) | |

| Years living with cancer | ||

| 0–1 year | 11 (44.0%) | |

| 2–5 years | 7 (28.0%) | |

| 6–10 years | 3 (12.0%) | |

| 10+ years | 4 (16.0%) | |

Data Analysis

The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, noting punctuation and pauses to help go beyond the words used by participants to detect any nuance in the meaning behind the words they chose to describe their experience. Data analysis relied on the constant comparative method, three levels of data coding used in constructivist grounded theory (initial, focused, and theoretical coding) (Charmaz, 2014), and theoretical sampling to categorize and map the process of how YAs try to live with advanced cancer. The analytic process began with reviewing each interview as a whole and taking notes with initial thoughts to obtain an overall impression of the contents of each interview. Then, each interview was reviewed line by line and/or in segments (i.e. initial coding) to identify and highlight codes. Using the constant comparative approach, codes were then organized into themes and categories, relating them to previously analyzed data (i.e. focused coding). Relationships between data, codes, themes, and categories were mapped, and broader conceptual categories were formed to create the scaffolding of the findings (i.e. theoretical coding). To generate this scaffold, the participants’ experiences were mapped onto the ICF model to see how a diagnosis of advanced cancer impacted YAs ability to participate in daily life and ways they tried to adapt (see Campbell et al., 2012, p. 2301). Theoretical sampling was applied by collecting and analyzing data concurrently and testing insights in subsequent interviews by asking specific probes related to previously collected data to determine the best type of data to elaborate a deeper analytical understanding of the experience and to confirm the emerging process (Draucker et al., 2007). For example, living in the liminal space was a theme that participants discussed during early interviews. If a participant did not organically discuss this space during a later interview, we asked directive probes to have them elaborate on whether living in this space was a key characteristic of their illness experience and when we asked them to elaborate as to why or why not. This concurrent process is consistent with the grounded theory method (Draucker et al., 2007; Walker & Myrick, 2006). Co-authors participated in the data analysis process by providing feedback on the progression of the coding when the first author (JA) presented on the emerging findings. Rigour was enhanced by staying as close as possible to the words used by participants when analyzing and coding data and by checking the theoretical construction generated against participants’ meanings of the phenomenon during interviews. In addition, reflexive journaling, memo writing, and keeping field notes were used to critically examine the first author’s influence on the research process and the co-creation of meaning with research participants. Qualitative data analysis software NVivo 10 version 12 was used to help organize codes, categories, and themes.

Findings

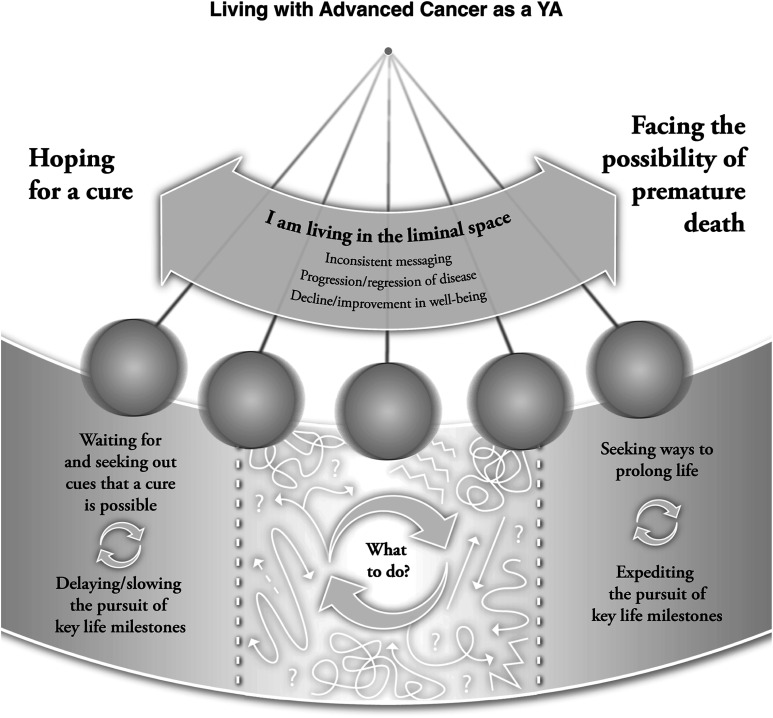

The YAs described living and navigating their day-to-day life with an advanced-stage cancer diagnosis as an oscillating experience swinging between two opposing possible outcomes of their illness: (1) hoping for a cure and (2) facing the possibility of premature death. Oscillating between these potential outcomes began with a diagnosis of advanced cancer and was characterized as living in a liminal space wherein the participants were uncertain how to continue to pursue and achieve life goals. As the participants swung towards having hope for a cure, they lived from one day to the next by (a) delaying life decisions and the pursuit of key milestones while (b) waiting for and seeking out social cues that a cure was possible before continuing to pursue said milestones. When swinging towards the possibility of premature death, the YAs shifted how they lived from one day to the next by (a) expediting the pursuit of key life milestones while (b) seeking ways to prolong life to increase the likelihood of reaching said milestones before end of life. Although the participants articulated two different ways of living from one day to the next, most were in the liminal space of oscillating between hoping for a cure and facing the possibility of premature death. The participants oscillated at different rates. Faster and more abrupt oscillations made life unpredictable and more difficult for the participants to know which way of living was best. Different factors emerged that influenced the rate of oscillation, including inconsistent and poor messaging from their oncologists or treatment team, progression or regression of their disease, and abrupt changes in physical functioning and mental health (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The process of living with advanced cancer.

Hoping for a Cure

For most of the YAs, being told they have stage 4, advanced, metastatic, or recurrent cancer evoked overwhelming thoughts of immediate rapid decline in physical functioning and mental health, and premature death. These thoughts completely disrupted their day-to-day life and diminished their sense of becoming an adult. The participants attempted to mitigate this disruption by (a) delaying major life decisions and the pursuit of key milestones while also (b) waiting for and seeking out social cues that a cure was possible before continuing to pursue said milestones unabated.

Delaying Major Life Decisions and the Pursuit of Key Milestones

Many of the participants described delaying making major life choices to reduce the impact of their illness on said choices. Some notable activities halted included having children, purchasing a home, pushing for career progression, returning to work or school, travelling, and dating. One participant (P018, 38-year-old woman living with breast cancer) reflected, ‘My husband and I were waiting to have family … but I needed to know [first if my cancer had progressed]’. There was a constant tension between waiting for favourable test results and pursuing young adult activities as highlighted by a 39-year-old man who had lived with advanced lung cancer for 3 years (P002): ‘Do I continue my career, or do I continue dating this person? Or should I just sort of give up and just focus on treatment … and on surviving?’ This young man’s commentary highlighted how, when waiting for favourable test results, he questioned whether to postpone or continue pursuing YA-related milestones. A 37-year-old man diagnosed with ameloblastoma (P025) described waiting as living with ‘a kind of tunnel vision’ with the hopes that ‘maybe the next [scan], in three months … or [later] this year there might be a cure for me’, at which point he could return to a typical life trajectory and the pursuit of key milestones. Thus, when the YAs were situated on the hopeful side of the pendulum, they were contemplating how, in what ways, or if at all, to pursue key life milestones while waiting for information or news about a possible cure. For many, life appeared to be framed as temporarily on hold.

Waiting for and Seeking Out Social Cues That a Cure Is Possible

As the YAs contemplated whether to delay or pursue young adult milestones, they also waited for and sought cues from their social surroundings to reinforce a belief that it was possible to overcome advanced-stage cancer. Cues were sought from multiple sources. The participants recounted their hopes of gaining access to novel cancer treatments and clinical trials they had heard about, as reflected in the comments of a 34-year-old woman with lung cancer (P011) that ‘they are testing these other drugs … so I am not closing off that possibility of that narrative [of survival]’. Conversations with other YAs who had survived cancer also provided hope, helping the participants believe that they too could outlive their illness, as recounted by a 31-year-old woman with stage 4 Hodgkin’s lymphoma (P012) who indicated that ‘Just meeting people that had survived cancer and realizing, oh, not everybody dies from it’. For others, the words and body language used by their oncologists and other specialists provided a glimmer of hope for a cure. The ‘“what the fuck” look [I got] when I asked him [their oncologist] if there was hope’ gave one 37-year-old woman (P009) the impression that she too could survive her stage 4 invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Waiting for and seeking out these cues from their social surroundings gave the YAs hope that they could outlive their cancer and return to a typical young adult life trajectory in time.

Facing the Possibility of Premature Death

The YAs also encountered cues that propelled towards the other end of the pendulum, the possibility of premature death. Receiving unfavourable test results, being told there was little possibility of a cure, and experiencing a decline in physical functioning and mental health prompted the participants to feel that they would not overcome their illness. This was associated with a sense of personal inadequacy, believing that they could somehow influence whether their treatment was effective. As the YAs oscillated towards this end of the pendulum, they shifted how they lived from one day to the next by (a) expediting the pursuit of key life milestones while (b) seeking ways to prolong life to increase the likelihood of reaching said milestones.

Expediting the Pursuit of Key Life Milestones

Facing the prospect of dying at a younger age before accomplishing key life milestones was difficult for the YAs to accept. They described feeling social pressure to achieve these milestones even amid a life-threatening illness. Feeling the constant ‘[I] need to catch up because you’re falling behind in your own goals or the goals that are ingrained in us [as young adults]’ described by a 27-year-old woman with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (P007) was common. Being in this position pushed the participants to expedite the pursuit of certain key life milestones before facing an imminent decline in physical functioning, mental health, and eventual death. One participant, a 38-year-old woman (P024) with stage 4 breast cancer, wanted to ‘do the things I want to do [now]’ because ‘I know my time is limited’. Another YA, a 30-year-old man with advanced-stage sarcoma (P005), similarly described his strategy of ‘Let’s focus on specific things like getting a job, or just focusing on myself and doing things that I enjoy … and not feeling held back’. Doing things now and not feeling held back by their cancer became a mindset that propelled YAs to accomplish key life milestones before significant decline in physical functioning and/or mental health prevented them from doing so. It allowed them to feel a sense of accomplishment and that their life was not wasted in the event they died prematurely. It also allowed some participants to build a living legacy, which for this 39-year-old woman living with metastatic breast cancer (P004) was a way to ‘do [more] things as a family to make memories together with our kids’ so that her young children may have a better recollection of who their mother was in the event she dies prematurely. This mindset also allowed other participants to address the social pressure they felt to accomplish their life goals even when faced with life-threatening cancer.

Seeking Ways to Prolong Life

The YAs oscillating towards the possibility of premature death began to let go of any hope of ever finding a cure. Acquiescing was not easy, as suggested by a 35-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer (P022) who stated, ‘it is hard to wrap your head around that’ when reflecting on the incurable nature of her illness. Based on their younger age, YAs felt they should be capable of overcoming their illness and struggled with the notion that this might not be possible. To cope, many began to view their illness as something that could be controlled and managed rather than cured. A 37-year-old man with stage 4 ameloblastoma (P025) remarked, ‘I’ve come to terms with the fact this [cancer] isn’t going away. But I may be able to control it’. This sentiment was similarly shared by a 38-year-old woman with stage 4 breast cancer (P024), who stated, ‘… even if this is not curable … [maybe] we can get to the point of [control]’. This framing appeared to prompt some of the participants to adopt specific health behaviours and/or seek alternative and complementary forms of treatment they perceived to slow cancer growth or metastases. Participating in activities connected to spirituality, mindfulness, meditation, physical exercise, and mental health was adopted with the belief that ‘[if] I treat my own body [better], I will probably impact it [my cancer] more over a longer term’, as shared by a 30-year-old man with stage 4 sarcoma (P005). This reframing provided the participants with some optimism that even if their illness was advanced, there were ways to improve the quality of the remainder of their life.

Living in the Liminal Space: Oscillating Between Hoping for a Cure and Facing the Possibility of Premature Death

Although the participants articulated two different ways of living from one day to the next, most were in the liminal space of oscillating between hoping for a cure and facing the possibility of premature death. The participants oscillated at different rates. Faster and more abrupt oscillations made life unpredictable and more difficult for the participants to know how to live from one day to the next. Some participants navigated this space by attempting to live as if they did not have cancer until they got confirmation that their illness was either curable or undeniably incurable. Different factors emerged that influenced the rate of oscillation and their capacity to situate on one side of the pendulum or the other. These factors included inconsistent and poor messaging from their oncology team, progression or regression of their disease, and abrupt changes in physical functioning and mental health.

Inconsistent and/or Poor Messaging From the Oncology Team

Participants described instances when they believed their oncologists or members of their treatment team were not forthright about the seriousness of their illness, as indicated by a 33-year-old woman with pilocytic astrocytoma (P010): ‘I don’t think that anyone was really straightforward with me in terms of what we were dealing with …’ The YAs commonly noted that they received mixed messaging about their cancer prognosis. For example, a 28-year-old man with stage 4 signet cell adenocarcinoma (P020) recounted that the word ‘incurable was used … and at the same time, achieving a state of remission was also used’. Similarly, a 35-year-old woman with stage 4 colorectal cancer (P014) indicated that her oncologist told her she was ‘cancer free’, which ‘didn’t make sense … there is still cancer on my liver’. This type of unclear messaging made it difficult for the YAs to comprehend the seriousness of their illness and the likelihood of ever becoming cancer free. One 27-year-old woman with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (P007) shared her confusion: ‘being told this a dire … and then meeting another doctor who understands … every patient’s different and you’re younger so you can be a little more positive about the situation … that was hard’. Without clear, concise, and consistent messaging, the participants had a more difficult time orienting themselves in the experience to determine how to live well from one day to the next.

Progression or Regression of Their Illness

Progression and/or regression of their disease propelled YAs to oscillate between hoping for a cure and facing the possibility of premature death. At times, this movement was instigated by receiving favourable or unfavourable results, most often from follow-up tests and/or scans. At other times, the movement was prompted by the anticipatory fear of what an upcoming scan could reveal. ‘The swings of anxiety coming up to a scan’ propelled one 35-year-old woman with metastatic breast cancer (P022) to oscillate between hoping for a cure and facing the possibility of premature death. For other participants, gaining access to a novel cancer treatment or clinical trial initiated this oscillation associated with progression or regression. A 30-year-old woman with stage 4 sarcoma (P001) oscillated towards the hopeful side when ‘They found this … miracle drug for me’, only to swing to the other side of the pendulum when the drug was unsuccessful, ‘I did everything the doctors told me to do … and still I relapsed!’. The fear associated with receiving results from a scan, gaining access to a clinical trial, and the progression/regression of the illness were instigators that pushed YAs into the liminal space between hope for a cure and having to face the prospect of premature death.

Changes in Physical Functioning and Mental Health

In addition to inconsistent messaging received from the treatment team and thoughts and feelings associated with the progression and regression of the illness, improvements or declines in physical functioning and mental health pushed YAs into the liminal space. Reduction in pain, cognitive impairment, and emotional distress/depression or improvements in mobility and function helped the YAs feel physically and emotionally stronger. This led several YAs to think they had the strength and resilience to overcome their illness. At 27 years of age, one woman with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (P007) explained that ‘my psychiatrist has helped me … And to be honest, I’m a little bit more hopeful … I don’t think that I’m going to die’. Some of the participants even believed that staying physically and mentally strong could help them live long enough for a novel cancer treatment or cure to be developed. ‘Maybe in a month or something, someone comes with a treatment that can help cure me’ was a reflection provided by a 22-year-old woman with stage 4 rectal cancer (P027) who was thus motivated to do what she could to manage her illness to maintain an acceptable quality of life.

However, the opposite was also true. A decline in physical functioning and poor mental health propelled the YAs in the opposite direction. A 31-year-old woman with stage 4 Hodgkin’s lymphoma (P012) explained that despite believing that she was on the path to remission, certain symptoms compelled her to think otherwise: ‘I’m closer to this [reality] of remission … but … there’s pain in certain parts of my body … spots where I had cancer … and that’s making me [re]think about it … what if this is like cancer coming back or something more severe?’. The oscillation associated with improvements and declines in physical functioning and mental health coincided with living in the liminal space between hope for a cure and dying prematurely and prompted a sense of uncertainty about how best the YAs should live from one day to the next.

Discussion

Our study illuminated the process by which YAs live from one day to the next with an advanced cancer diagnosis. Our interviews with participants suggested an oscillating experience of living in the liminal space between two opposing yet possible outcomes of their illness: (1) living with hope for a cure and (2) facing the possibility of dying prematurely. Oscillating at different rates and living within the liminal space shaped how the participants lived from one day to the next with an advanced diagnosis.

Previous research has demonstrated that individuals diagnosed and living with advanced cancer experience what has been coined as double awareness (Krause et al., 2015). Our findings describe this phenomenon in that the YAs hold two potential outcomes in mind and within their lived experience. Double awareness refers to balancing the possibilities that remain in life against the despair evoked by the finality of death (Colosimo et al., 2018). This theory challenged traditional views regarding death denial and the linear perspective of death processing proposed by Kübler-Ross (Colosimo et al., 2018). Double awareness posits that it is impossible to avoid awareness of death in the face of advanced disease, even while continuing to engage in life. The participants in our study neither accepted nor denied the possibility of death. Instead, they oscillated between hoping for a cure and facing the possibility of premature death. The process of oscillation reflects the dialectal tension of double awareness, of negotiating how to remain engaged in the world when facing the possibility of a life-limiting disease.

Research also suggests that adults of any age can experience the oscillation at different rates between these two opposing realities of living with a life-limiting illness (Arantzamendi et al., 2020; García-Rueda et al., 2016). In a meta-synthesis of the experience of people living with advanced-stage cancer, García-Ruedal et al. (2016) pointed to the prominence of people’s desire to find ways to balance the dialectical tension between remaining years left to live while also facing the reality of death and dying. However, these authors concluded that the literature is limited because research has yet to consider cultural, gender, or age-related differences in the desire to live within this reality and the processes by which people attempt to live within the dialectal tension of double awareness. For example, in a longitudinal grounded theory study of 27 patients (45–82 years of age) with either advanced lung or gastrointestinal cancer, Nissim et al. (2012) illustrated that participants engaged in a process of balancing the dialectal tension of double awareness that included valuing life in the present over the need to accomplish more. Our YA participants did not articulate the same desires or processes in their attempt to live meaningfully. Instead, they articulated the desire to achieve more, not less, even for those participants oscillating towards the possibility of dying prematurely.

Unlike older adults, YAs are at a stage of rapid change associated with developing their sense of self and finding ways to strive for independence while pursuing platonic and romantic relationships (Wiener et al., 2015). Shifting emotional attachments and keeping up with their peers’ social progression is fundamental to the YA identity (Johnston et al., 2016). The need to progress has been theorized as central to young adult identity, even for those with a life-threatening disease (Johnston et al., 2016; Soanes & Gibson, 2018). In a grounded theory study exploring the experiences, purposes, and meanings of supportive cancer care to young adults recently diagnosed with cancer, Soanes and Gibson (2018) found that participants were most concerned about protecting this young adult identity and proceeded to maintain this sense of self by interpreting cancer as a temporary interruption; that they would resume normal young adult life progression once they completed treatment. In contrast to our study, these findings were limited to a group of YAs between 19 and 24 years of age recently diagnosed with cancer and did not explore the illness experience of those living with advanced illness over months and years.

Like the findings of Soanes and Gibson (2018), our participants strove to protect their young adult identity by finding ways to minimize the impact of their illness on their capacity to achieve young adult milestones. Yet, they struggled to protect this identity within the dialectal tension of double awareness and to negotiate how to remain engaged in the world when realizing their illness may not be a temporary interruption; that they may have to live within the dichotomy of life and death prompted by their diagnosis.

Research has shown that the strongest predictors of good overall health-related quality of life for those living with advanced cancer are increased age, stable or improved physical and mental well-being, and treatment status (Zimmermann et al., 2011). Shifting from one treatment to another, fluctuations in disease progression/regression, and changes in physical functioning can be cumbersome for the mental health for any individual with an advanced cancer diagnosis but may be more difficult for YAs who are less adept at facing the possibility of death when compared to older adults (Alcaraz et al., 2020; Avery et al., 2020a). Our participants spoke adamantly of the mental health challenges associated with the progression or regression of their illness and jumping from one treatment or clinical trial to another in an attempt to control or treat their cancer. In addition, the inconsistent cues our participants perceived receiving from their healthcare providers made it more difficult for them to acknowledge the advanced nature of their illness and possibly less capable of accepting the duality of their circumstances. It is common among adults of any age to struggle to live within the dichotomy of double awareness (Umaretiya et al., 2023; Avery et al., 2020a). However, the inconsistent cues our participants perceived receiving from healthcare providers may be more common among the YA population (Joad et al., 2022).

In a qualitative study with 19 oncology specialists, Avery et al. (2020b) noted how these healthcare providers felt tension between the need to relay hopeful curative messages and articulate the realities of advanced/recurrent illness to their YA patients. This tension was reportedly not felt to such an extent when treating older adults. The emotional tension that healthcare providers experience when trying to balance hopeful messages with risk when treating YAs has been noted in other research (Burgers et al., 2022a, 2022b; Figueroa Gray et al., 2018; Wiener et al., 2015) and perhaps contributes to inconsistent messaging, as reported by our study participants. Further, this inconsistency in messaging from healthcare providers might have contributed to the difficulty YAs experienced in choosing a mode of living from one day to the next. The inconsistent messages may even contribute to the challenges reported by healthcare providers associated with the early introduction of palliative care. Research has shown that YAs may be more resistive to accepting early palliative care referrals because the word ‘palliative’ brings to mind a specific reality (i.e. death and dying) they may not be ready to think about. Inconsistent messaging may hinder the YAs' capacity to become more comfortable with the idea of death and dying and more primed to reject the early integration of palliative care (Avery et al., 2020a; Janardan & Wechsler, 2021). Our findings thus provide a theoretical rendering of the processes by which YAs attempt to live from one day to the next with advanced cancer, the challenges they encounter that previous research has not yet illuminated, and ways to consider how to improve the care we provide.

There are some limitations to this research. This constructivist grounded theory study represented the researcher’s interpretation of reality that was co-created with participants. We acknowledge that other interpretations of this reality and other realities could be co-created with different researchers and participants. Therefore, these findings represent a specific interpretation situated at a time and place and individuals. This articulated process could be different if YAs approaching the end of life were included. None of our participants disclosed they were medically defined as being at the end of life even if some believed they were on that trajectory. In addition, our sample does not represent the cultural diversity of Canada. Our participants were primarily women, affluent, and Canadian born. Those between 15 and 17 years of age, of various gender identities, or from different cultural groups could articulate different processes of living with advanced cancer. We also only interviewed each participant once. Conducting follow-up interviews could have revealed additional processes by having participants reflect on our emerging theory. For example, additional interviews could have provided more clarity around the concept of double awareness, oscillation, and tension. For example, follow-up interviews could have revealed nuances in the oscillating experience for those living with their illness for multiple years when compared to those living with advanced cancer for a shorter period. Young adults with young children may also experience a different process. Although we did not collect this demographic information, two of our participants disclosed during interviews that they had young children. We did not detect any differences in their process of living from one day to the next, but additional interviews with other young adults with children could have revealed other insights.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

There continues to be limited evidence and knowledge of how to support YAs living with advanced cancer. Our study provides a theoretical rendering of their illness experience, which can inform ways to integrate improved supportive care to better support this population. Few studies have explored the illness experience of these YAs, which has led to a dearth of knowledge and evidence of how to provide them with appropriate and timely supportive cancer care (Knox et al., 2017; Soanes & Gibson, 2018; Wiener et al., 2015). Our study is the first of three phases to develop an implementation strategy to improve the care for this population. In this first phase, we developed the framework, which is being used to inform Phase 2 (currently underway) to explore the perspective of oncology professionals, administrators, and program directors involved in the care of AYAs. Findings from this second phase will be used to co-develop actions and priorities for research and programming to understand what would be needed to integrate improved support to help YAs with advanced cancer to live from one day to the next (phase 3) with the YAs themselves and with the oncology professionals who support them. In addition, a secondary data analysis is also underway to explore in more depth how YAs lived within the dichotomy of double awareness. Double awareness has yet to be thoroughly explored in the YA population (Figueroa Gray et al., 2018; Rodin et al., 2018). Our interviews are rich in content and provide an opportunity to explore these data using double awareness as a theoretical lens. Findings from this secondary analysis can inform future psychotherapeutic interventions intended to treat and prevent psychosocial and end-of-life distress in YAs with advanced cancer.

Conclusion

In summary, we have provided a theoretical rendering of the YAs' experience living from one day to the next with a diagnosis of advanced cancer. Our framework provides the opportunity to explore how to tailor future interventions for these YAs. Specific areas where our framework could be utilized include understanding how to approach onco-fertility for YAs, exploring how to enhance clinical trial recruitment as YAs oscillate between these two possible disease outcomes (Canzona et al., 2021; Docherty et al., 2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Designs that Cells and, specifically, Ava Schroedl for her design of Figure 2.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research study was conducted with support from C17 and funded by the Michael Kamin Hart Research Fund (AYA Program, Princess Margaret Cancer Center), the Canadian Cancer Clinical Trials Network (3CTN), and the Canadian Cancer Society.

ORCID iDs

Jonathan Avery https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7347-6224

A. Fuchsia Howard https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5704-1733

References

- Abdelaal M., Avery J., Chow R., Saleem N., Fazelzad R., Mosher P., Hannon B., Zimmermann C., Al-Awamer A. (2023). Palliative care for adolescents and young adults with advanced illness: A scoping review. Palliative Medicine, 37(1), 88–107. 10.1177/02692163221136160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelaal M., Mosher P. J., Gupta A., Hannon B., Cameron C., Berman M., Moineddin R., Avery J., Mitchell L., Li M., Zimmermann C., Al-Awamer A. (2021). Supporting the needs of adolescents and young adults: Integrated palliative care and psychiatry clinic for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Cancers, 13(4), 770. 10.3390/cancers13040770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaraz K. I., Wiedt T. L., Daniels E. C., Yabroff K. R., Guerra C. E., Wender R. C. (2020). Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: A blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 70(1), 31–46. 10.3322/caac.21586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfano C. M., Leach C. R., Smith T. G., Miller K. D., Alcaraz K. I., Cannady R. S., Wender R. C., Brawley O. W. (2019). Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: A blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 35–49. 10.3322/caac.21548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantzamendi M., García-Rueda N., Carvajal A., Robinson C. A. (2020). People with advanced cancer: The process of living well with awareness of dying. Qualitative Health Research, 30(8), 1143–1155. 10.1177/1049732318816298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J., Žukauskienė R., Sugimura K. (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery J., Geist A., D’Agostino N., Kawaguchi S. K., Mahtani R., Mazzotta P., Mosher P. J., Al- Awamer A., Kassam A., Zimmermann C., Samadi M., Tam S., Srikanthan A., Gupta A. (2020. b). It’s more difficult…”: Clinicians’ experience providing palliative care to adolescents and young adults diagnosed with advanced cancer. JCO oncology practice, 16(1), Article e100–e108. 10.1200/JOP.19.00313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery J., Mosher P. J., Kassam A., Srikanthan A., D'Agostino N., Zimmermann C., Castaldo Y., Aubrey R., Rodrigues C. M., Thavaratnam A., Samadi M., Al-Awamer A., Gupta A. (2020. a). Young adult experience in an outpatient interdisciplinary palliative care cancer clinic. JCO oncology practice, 16(12), Article e1451–e1461. 10.1200/OP.20.00161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery J., Wong E., Harris C., Chapman S., Uppal S., Shanawaz S., Edwards A., Burnett L., Vora T., Gupta A. (2022). The transformation of adolescent and young adult oncological and supportive care in Canada: A mixed methods study. Current Oncology, 29(7), 5126–5138. 10.3390/curroncol29070406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird H., Patterson P., Medlow S., Allison K. R. (2019). Understanding and improving survivorship care for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 8(5), 581–586. 10.1089/jayao.2019.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat L. P., Galtieri L. R., Szalda D., Schwartz L. A. (2016). Assessing the psychosocial needs and program preferences of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 24(2), 823–832. 10.1007/s00520-015-2849-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman A. M., Livingston J. A., Merriman K., Hildebrandt M., Wang J., Dibaj S., McQuade J., You N., Ying A., Barcenas C., Bodurka D., DePombo A., Lee H. J., de Groot J., Roth M. (2020). Long-term survival among 5-year survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer. Cancer, 126(16), 3708–3718. 10.1002/cncr.33003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornbaum C., Doyle P., Skarakis-Doyle E., Theurer J. (2013). A critical exploration of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework from the perspective of oncology: Recommendations for revision. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 6, 75–86. 10.2147/JMDH.S40020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers V. W. G., van den Bent M. J., Darlington A. S. E., Gualthérie van Weezel A. E., Compter A., Tromp J. M., Lalisang R. I., Kouwenhoven M. C. M., Dirven L., Harthoorn N. C. G. L., Troost-Heijboer C. A., Husson O., van der Graaf W. T. A. (2022. a). A qualitative study on the challenges health care professionals face when caring for adolescents and young adults with an uncertain and/or poor cancer prognosis. ESMO Open, 7(3), 100476. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2022.100476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers V. W. G., van den Bent M. J., Dirven L., Lalisang R. I., Tromp J. M., Compter A., Kouwenhoven M., Bos M. E. M. M., de Langen A., Reuvers M. J. P., Franssen S. A., Frissen S. A. M. M., Harthoorn N. C. G. L., Dickhout A., Noordhoek M. J., van der Graaf W. T. A., Husson O. (2022. b). “Finding my way in a maze while the clock is ticking”: The daily life challenges of adolescents and young adults with an uncertain or poor cancer prognosis. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 994934. 10.3389/fonc.2022.994934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K. L., Pusic A. L., Zucker D. S., McNeely M. L., Binkley J. M., Cheville A. L., Harwood K. J. (2012). A prospective model of care for breast cancer rehabilitation: Function. Cancer, 118(8 Suppl), 2300–2311. 10.1002/cncr.27464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canzona M. R., Victorson D. E., Murphy K., Clayman M. L., Patel B., Puccinelli-Ortega N., McLean T. W., Harry O., Little-Greene D., Salsman J. M. (2021). A conceptual model of fertility concerns among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 30(8), 1383–1392. 10.1002/pon.5695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Cheville A. L., Mustian K., Winters-Stone K., Zucker D. S., Gamble G. L., Alfano C. M. (2017). Cancer rehabilitation: An overview of current need, delivery models, and levels of care. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America, 28(1), 1–17. 10.1016/j.pmr.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark J. K., Fasciano K. (2015). Young adult palliative care: Challenges and opportunities. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 32(1), 101–111. 10.1177/1049909113510394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coburn N. G., Gupta S., Li Q., Kassam A., Rapoport A., Widger K., Chalifour K., Baxter N. N., Nathan P. C., Sutradhar R. (2023). Symptom severity, specialty palliative care, and subsequent symptom control among adolescents and young adults with cancer: A population-based study. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 41(16_suppl), Article e24127–e24127. 10.1200/jco.2023.41.16_suppl.e24127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colosimo K., Nissim R., Pos A. E., Hales S., Zimmermann C., Rodin G. (2018). “Double awareness” in psychotherapy for patients living with advanced cancer. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 28(2), 125–140. 10.1037/int0000078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N., Lincoln Y. (2005). The handbook of qualitative research. In Denzin N., Lincoln Y. (Eds.), (3rd ed.). Sage Publication. [Google Scholar]

- Docherty S. L., Crane S., Haase J. E., Robb S. L. (2019). Improving recruitment and retention of adolescents and young adults with cancer in randomized controlled clinical trials. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 33(4), 10. 10.1515/ijamh-2018-0215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draucker C. B., Martsolf D. S., Ross R., Rusk T. B. (2007). Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17(8), 1137–1148. 10.1177/1049732307308450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa Gray M., Ludman E. J., Beatty T., Rosenberg A. R., Wernli K. J. (2018). Balancing hope and risk among adolescent and young adult cancer patients with late-stage cancer: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 7(6), 673–680. 10.1089/jayao.2018.0048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Rueda N., Carvajal Valcárcel A., Saracíbar-Razquin M., Arantzamendi Solabarrieta M. (2016). The experience of living with advanced-stage cancer: A thematic synthesis of the literature. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(4), 551–569. 10.1111/ecc.12523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist L. S., Galantino M. L., Wampler M., Marchese V. G., Morris G. S., Ness K. K. (2009). A framework for assessment in oncology rehabilitation. Physical Therapy, 89(3), 286–306. 10.2522/ptj.20070309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A. A., Papadakos J. K., Jones J. M., Amin L., Chang E. K., Korenblum C., Santa Mina D., McCabe L., Mitchell L., Giuliani M. E. (2016). Reimagining care for adolescent and young adult cancer programs: Moving with the times. Cancer, 122(7), 1038–1046. 10.1002/cncr.29834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janardan S. K., Wechsler D. S. (2021). Caught in the in-between: Challenges in treating adolescents and young adults with cancer. JCO oncology practice, 17(6), 299–301. 10.1200/OP.21.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joad A. S. K., Hota A., Agarwal P., Patel K., Patel K., Puri J., Shin S. (2022). “I want to live, but…” the desire to live and its physical, psychological, spiritual, and social factors among advanced cancer patients: Evidence from the APPROACH study in India. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 153. 10.1186/s12904-022-01041-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston B., Jindal-Snape D., Pringle J., Gold L., Grant J., Dempsey R., Scott R., Carragher P. (2016). Understanding the relationship transitions and associated end of life clinical needs of young adults with life-limiting illnesses: A triangulated longitudinal qualitative study. Sage Open Medicine, 4, 1–14. 10.1177/2050312116666429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston E. E., Alvarez E., Saynina O., Sanders L. M., Bhatia S., Chamberlain L. J. (2018). Inpatient utilization and disparities: The last year of life of adolescent and young adult oncology patients in California. Cancer, 124(8), 1819–1827. 10.1002/cncr.31233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox M. K., Hales S., Nissim R., Jung J., Lo C., Zimmermann C., Rodin G. (2017). Lost and stranded: The experience of younger adults with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(2), 399–407. 10.1007/s00520-016-3415-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause S., Rydall A., Hales S., Rodin G., Lo C. (2015). Initial validation of the death and dying distress scale for the assessment of death anxiety in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 49(1), 126–134. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le J., Dorstyn D. S., Mpofu E., Prior E., Tully P. J. (2018). Health-related quality of life in coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis mapped against the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 27(10), 2491–2503. 10.1007/s11136-018-1885-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur M., Desrosiers J., St-Cyr T. D. (2007). Comparing the Disability Creation Process and International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health models. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(5 Suppl), 233–242. 10.1177/000841740707405S02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood B. J., Ntukidem O. L., Ehrman S. E., Schnell P. M., Klemanski D. L., Bhatnagar B., Lustberg M. (2021). Palliative care referral patterns for adolescent and young adult patients at a comprehensive cancer center. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 10(1), 109–114. 10.1089/jayao.2020.0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews J., Hannon B., Zimmermann C. (2021). Models of integration of specialized palliative care with oncology. Current Treatment Options in Oncology, 22(5), 44. 10.1007/s11864-021-00836-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrady M. E., Perez M. N., Bernstein J., Strenk M., Kiger M. A., Norris R. E. (2022). Adherence and barriers to inpatient physical therapy among adolescents and young adults with hematologic malignancies. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 11(6), 605–610. 10.1089/jayao.2021.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills J., Bonner A., Francis K. (2006). Adopting a constructivist approach to grounded theory: Implications for research design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 12(1), 8–13. 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2006.00543.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim R., Rennie D., Fleming S., Hales S., Gagliese L., Rodin G. (2012). Goals set in the land of the living/dying: A longitudinal study of patients living with advanced cancer. Death Studies, 36(4), 360–390. 10.1080/07481187.2011.553324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottelmann L., Groenvold M., Vejlgaard T. B., Petersen M. A., Jensen L. H. (2021). Early, integrated palliative rehabilitation improves quality of life of patients with newly diagnosed advanced cancer: The Pal-Rehab randomized controlled trial. Palliative Medicine, 35(7), 1344–1355. 10.1177/02692163211015574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perin C., Bolis M., Limonta M., Meroni R., Ostasiewicz K., Cornaggia C. M., Alouche S. R., da Silva Matuti G., Cerri C. G., Piscitelli D. (2020). Differences in rehabilitation needs after stroke: A similarity analysis on the ICF core set for stroke. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4291. 10.3390/ijerph17124291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto M., Calafiore D., Piccirillo M. C., Costa M., Taskiran O. O., de Sire A. (2022). Breast cancer survivorship: The role of rehabilitation according to the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health - a scoping review. Current Oncology Reports, 24(9), 1163–1175. 10.1007/s11912-022-01262-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin G., Lo C., Rydall A., Shnall J., Malfitano C., Chiu A., Panday T., Watt S., An E., Nissim R., Li M., Zimmermann C., Hales S. (2018). Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM): A randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention for patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 36(23), 2422–2432. 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J. K., Raj V. S., Fu J. B., Wisotzky E. M., Smith S. R., Kirch R. A. (2015). Cancer rehabilitation and palliative care: Critical components in the delivery of high-quality oncology services. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 23(12), 3633–3643. 10.1007/s00520-015-2916-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soanes L., Gibson F. (2018). Protecting an adult identity: A grounded theory of supportive care for young adults recently diagnosed with cancer. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 81, 40–48. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe S. B. (2011). A review of Canadian health care and cancer care systems. Cancer, 117(10 Suppl), 2241–2244. 10.1002/cncr.26053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo I., Krishnan A., Lee G. L. (2019). Psychosocial interventions for advanced cancer patients: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 28(7), 1394–1407. 10.1002/pon.5103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaretiya P. J., Fisher L., Altschuler A., Kushi L. H., Chao C. R., Vega B., Rodrigues G., Josephs I., Brock K. E., Buchanan S., Casperson M., Fasciano K. M., Kolevska T., Lakin J. R., Lefebvre A., Schwartz C. M., Shalman D. M., Wall C. B., Wiener L., Mack J. W. (2023). “The simple life experiences that every other human gets”: Desire for normalcy among adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 70(1), Article e30035. 10.1002/pbc.30035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D., Myrick F. (2006). Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 547–559. 10.1177/1049732305285972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L., Weaver M. S., Bell C. J., Sansom-Daly U. M. (2015). Threading the cloak: Palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clinical Oncology in Adolescents and Young Adults, 5, 1–18. 10.2147/COAYA.S49176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildeboer A. T., Stallinga H. A., Roodbol P. F. (2022). Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) core set for diabetes mellitus from nurses’ perspective using the Delphi method. Disability & Rehabilitation, 44(2), 210–218. 10.1080/09638288.2020.1763485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B., Isaacson S. (2012). Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult patients with cancer and survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 30(11), 1221–1226. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann C., Burman D., Swami N., Krzyzanowska M,K., Leighl N., Moore M., Rodin G., Tannock I. (2011). Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer: Official Journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, 19(5), 621–629. 10.1007/s00520-010-0866-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]