Abstract

Recently, the DinR protein was established as the cellular repressor of the SOS response in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis. It is believed that DinR functions as the repressor by binding to a consensus sequence located in the promoter region of each SOS gene. The binding site for DinR is believed to be synonymous with the formerly identified Cheo box, a region of 12 bp displaying dyad symmetry (GAAC-N4-GTTC). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays revealed that highly purified DinR does bind to such sites located upstream of the dinA, dinB, dinC, and dinR genes. Furthermore, detailed mutational analysis of the B. subtilis recA operator indicates that some nucleotides are more important than others for maintaining efficient DinR binding. For example, nucleotide substitutions immediately 5′ and 3′ of the Cheo box as well as those in the N4 region appear to affect DinR binding. This data, combined with computational analyses of potential binding sites in other gram-positive organisms, yields a new consensus (DinR box) of 5′-CGAACRNRYGTTYC-3′. DNA footprint analysis of the B. subtilis dinR and recA DinR boxes revealed that the DinR box is centrally located within a DNA region of 31 bp that is protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage in the presence of DinR. Furthermore, while DinR is predominantly monomeric in solution, it apparently binds to the DinR box in a dimeric state.

Based upon sequence comparisons, it has been hypothesized that the Bacillus subtilis protein DinR is the functional homolog of the Escherichia coli SOS transcriptional repressor, LexA (20, 21). Indeed, recently published data has firmly established DinR as the transcriptional repressor of the SOS system in B. subtilis (5, 16, 27). Although it is only 34% identical to LexA, DinR demonstrates many biochemical and physical properties that are reminiscent of LexA. For example, like that of LexA, the deduced amino acid sequence of DinR predicts two distinct domains within the protein. DinR has most homology to LexA and other LexA-like proteins in its carboxyl-terminal domain (10, 27). This C-terminal domain is thought to be primarily responsible for the cooperative dimerization of the normally monomeric LexA protein at its target site in DNA (8, 22, 23, 25). The C-terminal domain also contains a conserved Ala-Gly cleavage site as well as the appropriately spaced serine and lysine residues that have been identified as critical for autodigestion (14). Indeed, like LexA, DinR undergoes RecA-independent autocatalysis at alkaline pH and RecA-mediated autocatalysis under more physiological conditions (16, 27). Such cleavage inactivates repressor function, thereby allowing DinR-regulated genes to be expressed.

Despite the notion that DinR displays transcriptional repressor activity that is comparable to that of LexA (16), there is in fact little homology between the amino-terminal DNA binding domains of the two proteins (10, 27). In addition to the obvious lack of primary sequence homology, the typical repressor-like, helix-turn-helix motif present in LexA is not immediately obvious in DinR. This disparity coincides with the appearance of completely distinct DNA binding sequences in the two repressors. In E. coli and many other gram-negative organisms, the SOS box is a region of 16 bp that displays dyad symmetry [5′-CTGT-(AT)4-ACAG-3′] (13, 26). In several gram-positive bacteria (e.g., B. subtilis and Mycobacteria sp.) (2, 4, 17, 19), the binding site for DinR is thought to be the previously described Cheo box, a region of 12 bp with dyad symmetry (5′-GAAC-N4-GTTC-3′) but no homology to the gram-negative SOS box.

It has recently been suggested that the B. subtilis DinR protein should be renamed LexA (16). Given the huge differences in the recognition sites between the E. coli LexA protein and the gram-positive DinR-like proteins, however (4, 17, 19, 27; see below), we propose retaining the descriptive name DinR (damage inducible repressor) rather than renaming the protein LexA (originally defined as locus for X-ray sensitivity A [7]) and using the term DinR box to describe the binding site for DinR to avoid confusion between it and the commonly referred to SOS box of E. coli.

We have previously purified the B. subtilis DinR protein to homogeneity (27) and shown that it does bind to the proposed DinR binding site in the B. subtilis recA promoter region but does not bind to certain mutant sequences located within the previously identified Cheo box. The availability of the highly purified B. subtilis DinR protein has enabled us to extend these studies and perform a detailed molecular analysis of the B. subtilis DinR box. Indeed, by using a combination of gel electrophoretic mobility shift assays, hydroxyl radical footprint protection assays, and recA-lacZ transcriptional fusions, we have determined that certain bases within the previously defined Cheo box are more critical for binding than others. This data, together with computational analyses of potential binding sites in other gram-positive organisms, allows us to propose a new consensus DinR box, 5′-CGAACRNRYGTTYC-3′.

(This research was conducted by K. Winterling and J. Sun in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The B. subtilis strain used in this study, YB886A, serves as a wild-type strain and is cured of all known prophages. E. coli DH5α (GIBCO-Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) and GBE180 (DH5α pcnB1) were used for routine cloning and maintenance of plasmids (27).

The recA fragment used for mutational analysis of the Cheo box is essentially the previously described 202-bp HindIII-Sau3AI fragment encompassing the promoter of the B. subtilis gene recA (2, 3, 27). Various mutations in the recA Cheo box were made via site-directed mutagenesis by following the specifications of the ExSite kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) (24).

Media and growth conditions.

B. subtilis strains were maintained on tryptose blood agar base medium, and liquid cultures were grown in antibiotic medium 3 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) or nutrient broth (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, United Kingdom) with aeration at 37°C. E. coli strains were grown on Luria-Bertani agar or in Luria-Bertani broth. Ampicillin (50 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (20 μg/ml), kanamycin (30 μg/ml), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mM) (Gold Biotechnology, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.) were added as required.

β-Galactosidase assays.

DNA damage-inducible promoter activity of the recA-lacZ and din-lacZ fusions was examined by measuring β-galactosidase activity as previously described (27). Briefly, B. subtilis cultures were grown with aeration at 37°C in nutrient broth supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract. Cultures were grown to early exponential phase, when an aliquot was removed and the culture was divided in half. Mitomycin (0.5 μg/ml) was added to one-half of the culture, and 1-ml aliquots were taken from the induced and uninduced cultures after 90 min of additional incubation. After the absorbance (optical density at 595 nm) of each sample was spectrophotometrically measured, the cells were harvested and washed in 0.5 ml of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). The supernatant was decanted, and the pellet was placed in a dry ice-ethanol bath. The pellet was subsequently resuspended in 0.64 ml of Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol [pH 7.0]) (15), 0.16 ml of a lysozyme solution (2.5 mg/ml in Z buffer) was added, and the sample was incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Eight microliters of 10% Triton X-100 was added, and the samples were warmed to 30°C. β-Galactosidase activity was calculated by the method of Miller (15).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

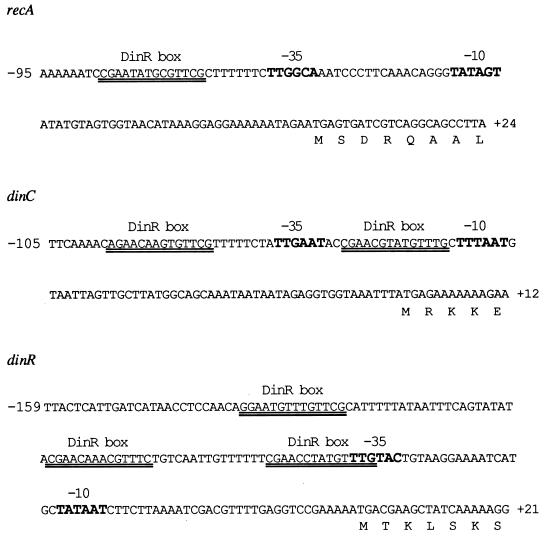

The exact location of each DinR box relative to the −35 and −10 promoter elements as well as the translational start site of each gene is shown in Fig. 1. The wild-type and mutant recA DinR boxes used in this assay were gel-purified synthetic oligonucleotides that varied in length from 60 to 67 bp. Complementary single-stranded oligonucleotides were annealed together by mixing equimolar amounts of each oligonucleotide, thus producing short regions of double-stranded DNA (27). In addition, oligonucleotides were similarly synthesized, purified, and annealed so that they corresponded to the wild-type promoter sequences of dinA and dinB. All of these probes were designed so that the DinR binding site was centered, with approximately 26 bp of wild-type sequence flanking each side.

FIG. 1.

Location of DinR boxes in the promoter regions of the B. subtilis recA, dinC, and dinR genes. The respective −35 and −10 promoter elements for each gene are in slightly larger, bold-faced letters. The DinR boxes are double underlined. The recA-DinR box is centered at −51 relative to the −35 promoter. The two dinC-DinR boxes are located at −24 and −53 relative to the −35 and −10 elements. The three dinR-DinR boxes are located at −39, −67, and −104 relative to the −35 promoter.

dinC contains two putative DinR binding sites, which are located close to its promoter elements (Fig. 1). One putative DinR site is located between the −35 and −10 promoter elements (at −56 to −68 bp relative to the initiator codon) and was designated the −24 site for convenience (Fig. 1). The other site is located about 30 bp upstream of the first site (at −86 to −98 bp relative to the initiator codon) and is called the −53 site (Fig. 1). To assess the ability of DinR to bind to each of these sites, three probes were synthesized, one that contained the −24 site, one that contained the −53 site, and one that contained both the −24 and the −53 sites.

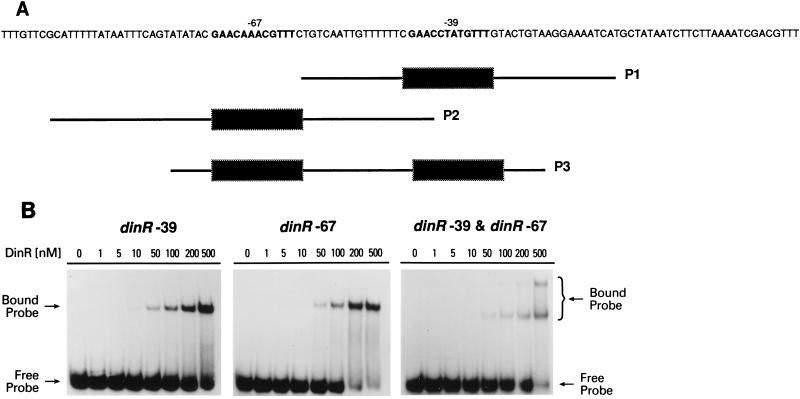

The dinR gene has three potential binding sites, two of which are located close to the promoter region (Fig. 1) and are denoted the −39 and −67 DinR binding sites. The third site is further upstream and is called the −104 DinR box. This latter box has previously been shown to play no apparent role in regulating dinR (5) and was therefore not studied further in the gel mobility shift assay. As a consequence, we synthesized only three probes, one that contained only the −39 or the −67 site and one that contained both of these sites.

The oligonucleotides were designed so that when they were annealed together, both ends had 5′ T and/or A extensions that could be labeled with [32P]dATP and/or [32P]dTTP by a Klenow fill-in reaction. Reaction mixtures (20 μl each) containing approximately 3.0 ng of labeled probe and various amounts of DinR were incubated at room temperature for 25 min in binding buffer (150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 0.2 mM EDTA, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol [vol/vol], 50 μg of bovine serum albumin [BSA] per ml). Protein-DNA complexes were separated in native polyacrylamide gels (5 or 6% acrylamide). Gels were dried and subsequently exposed to Kodak XAR X-ray film for appropriate periods of time. Dried gels were also exposed to Molecular Dynamics phosphor screens and scanned into the Molecular Dynamics PhosphoImager. Subsequent quantitation was performed with Image Quant version 1.1 software.

Determination of the oligomeric state of DinR in solution and DinR bound to target DNA.

To determine the oligomeric state of DinR in solution, we compared its relative sedimentation in a glycerol gradient to that of the E. coli LexA protein. Highly purified DinR and LexA proteins (5 μg each) were loaded onto separate 5 to 30% linear glycerol gradients in buffer D [10 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES)–NaOH (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 200 mM NaCl]. Each gradient also contained 5 μg of BSA, 5 μg of ovalbumin, and 2 μg of cytochrome c as internal molecular weight standards. Ultracentrifugation was carried out for 26 h at 49,000 rpm with a SW60Ti rotor. Fractions (100 μl each) were collected, and proteins were separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gradient gels containing 9 to 19% polyacrylamide. Proteins were subsequently visualized by staining the gel with silver.

The oligomeric state of DinR when it is bound to its target sequence was determined by employing an electrophoretic mobility shift assay-based protocol developed by Orchard and May (18). The DNA fragments used in this experiment were identical to those described in the preceding section. The protein-DNA complexes were formed as described above and separated in native polyacrylamide gels whose acrylamide concentrations ranged from 4.5 to 10% (4.5, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10%). In addition to the DinR-DNA complexes, a sample of purified DinR and a set of nondenatured protein standards (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) were determined empirically. The lanes containing the DinR-DNA complexes were excised from each of the gels, dried, and subsequently exposed to Kodak XAR X-ray film for appropriate periods of time. The remainder of the gel, containing the purified DinR and the nondenatured protein standards, was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250. The distances migrated by each of the DinR-DNA complexes, the DinR protein alone, and each of the standards were measured and then divided by the distance travelled by the dye (bromophenol blue) in each lane. This calculation yields the relative mobility (Rf) of each protein or protein-DNA complex. The logarithm of the Rf was then plotted for each protein standard as a function of gel concentration. The slope of the line for each protein standard, called the retardation coefficient (Kr), was subsequently plotted as a function of the molecular weight of each standard. The Kr was determined for each DinR-DNA complex, for the free (unbound) DNA, and for the DinR alone. The derived standard curve was subsequently used to calculate the molecular weight of each protein-DNA complex, the DNA, and the DinR. Subtracting the molecular weight of the DNA from that of the DinR-DNA complex yields the apparent molecular weight of the protein associated with each protein-DNA complex.

Labeled DNA for hydroxyl radical footprint analysis.

Approximately 15 μg of PCR primer, DINR01 (5′-GCGAAGCTTCTCATGATCATAACCTC-CAAC-3′), RECA01 (5′-GCGAAGCTTACATGATTTTCTGATACATTA-3′), or RECA02 (5′-CGCGAATTCCTTTTATGTTACACTACATA-3′), was 5′ radiolabeled in separate reactions with T4 polynucleotide kinase. Briefly, 10 U of T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) was used to singly radioactively label each PCR primer in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 15 μg of PCR primer (DINR01, RECA01, or RECA02), 1× T4 PNK reaction buffer (70 mM Tris · HCl [pH 7.6], 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol), and 50 μCi of [γ-32P]dATP at 6,000 Ci/mmol for 30 to 60 min at 37°C. Radioactive primers were used in standard PCRs to obtain the dinR and recA promoter sequences in 100-μl reaction mixtures containing 10 μl of labeled primer (from the labeling reaction), 1× Vent polymerase buffer, 6 μg of complementary unlabeled PCR primer, 270 ng of B. subtilis YB886A chromosomal DNA, 10 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, and 2 U of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCR DNA was precipitated and separated on a native 8% polyacrylamide gel made with 1× Tris-borate-EDTA. After separation, the wet gel was exposed to autoradiography film to identify the radioactive PCR product. The radioactive dinR and recA DNAs were gel purified by soaking a crushed gel slice in 700 μl of TE (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 8.0], 1 mM EDTA) buffer overnight. The radioactive DNAs were filtered through series 8000 microcentrifuge filtration devices (Lida Manufacturing Corporation), precipitated, dissolved in TE buffer, and stored at 3,000 to 5,000 cpm/μl.

Hydroxyl radical footprint analysis.

Equal volumes of labeled DNA (approximately 60,000 cpm) and DinR (diluted into glycerol-free 2× binding buffer [27]) were incubated at room temperature for 25 min. Labeled DNA from dinR-DinR or recA-DinR complexes was gel purified in the same manner as the labeled PCR products described above. In a typical 40-μl reaction mixture, 2 μl of 1 mM Fe-EDTA (50 μM final) and 2 μl of 20 mM sodium ascorbate (1 mM final) were pipetted onto the side of the reaction tube. Hydroxyl radical cleavage was initiated by adding 2 μl of a 1:250 dilution of 30% hydrogen peroxide solution into the existing drop (0.0075% final) and the DNA solution for 2.5 min. Cleavage was stopped by adding 1/10 volume of stop solution containing 50% glycerol and 10 mM EDTA. Protein-DNA complexes were separated by loading the cleavage reaction mixtures immediately onto a native 5% polyacrylamide–0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA gel.

G-specific reaction.

In a typical 200-μl reaction mixture, approximately 20,000 cpm of singly labeled DNA was added to 20 μl of 10× G-specific reaction buffer (0.5 M sodium cacodylate-10 mM EDTA) and 160 μl of water. One microliter of straight dimethyl sulfate was added to the tube. The reaction mixture was mixed immediately and incubated for 1 min before being briefly spun in a microcentrifuge. Fifty microliters of stop solution was added (1.5 M sodium acetate, 1 M β-mercaptoethanol, 0.004 μg of sonicated calf thymus DNA per ml), and the DNA was precipitated and dissolved in 90 μl of TE buffer. Ten microliters of piperidine was added and incubated at 90°C for 30 min. The DNA was dried to completion in a speed-vac concentrator. The dried DNA was dissolved twice in 20 μl of water and redried. The DNAs were finally dissolved in 40 to 50 μl of TE buffer and stored at 4°C.

Sequencing gel analysis of hydroxyl radical footprint.

Approximately 5,000 cpm from each sample was placed into separate Eppendorf tubes and dried completely in a speed-vac concentrator. Dried DNAs were dissolved in 4 μl of formamide loading buffer (100% formamide, xylene cylanol, bromophenol blue) and heated to 95°C for 2 min. Samples were immediately placed on ice and loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide-8 M urea sequencing gel. After analysis, gels were dried and exposed to autoradiography film or to a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager screen.

RESULTS

Regulation of damage-inducible genes in B. subtilis.

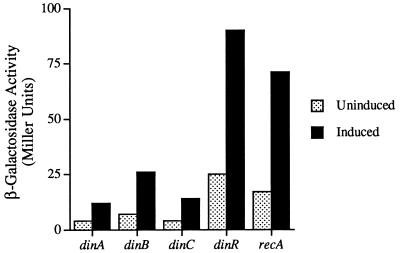

All living organisms are exposed to a variety of synthetic and natural DNA-damaging agents. The differential regulation of a response for coping with such damage would allow cells to respond to the extent of DNA damage by inducing only proteins that are required to efficiently repair all of the damaged DNA. In E. coli, differential regulation of SOS genes occurs and is achieved, at least in part, by variation of the affinity of the transcriptional repressor, LexA, for its binding site (reference 13 and references therein). Analysis of the levels of β-galactosidase produced by various din-lacZ fusions revealed that the basal level of B. subtilis din expression also varies considerably (Fig. 2). Obviously, such differences in expression could, in theory, be achieved by differential promoter activity or by alteration of the affinity of the repressor for its binding site. While previous studies have demonstrated that DinR binds to the Cheo box upstream of recA, dinB, dinC, and dinR (5, 16, 27), the relative affinity of DinR for each site is largely unknown. Interestingly, gel electrophoretic mobility shift assays of the dinA and dinB DinR boxes (Fig. 3) revealed that DinR binds to both boxes with roughly the same affinity and that these affinities are qualitatively similar to those of the recA-DinR box (27) and the dinR-DinR boxes (see below). Such observations suggest, therefore, that at least for the din genes assayed here, differential expression is achieved via differential promoter activities rather than differential operator affinities. This conclusion is also supported by our observation that all of the fusions were induced to the same extent (fourfold) under mild inducing conditions. If regulation was primarily at the level of operator binding, one might have expected the din-lacZ fusions to exhibit much more variable induction ratios.

FIG. 2.

Expression of B. subtilis dinA-lacZ, dinB-lacZ, dinC-lacZ, dinR-lacZ, and recA-lacZ transcriptional fusions. The various constructs were present in a single copy due to integration at the amyE locus. The SOS regulon was induced, where noted, by the addition of 0.5 μg of mitomycin per ml, cultures were harvested 90 min later, and the level of β-galactosidase activity was determined. The data for the dinR-lacZ fusion was taken from the study of Haijema et al. (5), and that for the recA-lacZ fusion, taken from the study of Winterling et al. (27), was used for comparison.

FIG. 3.

Binding of DinR to the DinR box located upstream of dinA and dinB. Radiolabeled dinA and dinB promoter fragments (3.0 ng or ∼3.4 nM) were incubated with various concentrations of DinR (nanomolar monomer) as indicated at the top of each lane. Reactions were performed at room temperature for 25 min. Protein-DNA complexes were separated in native polyacrylamide gels (5% acrylamide) and visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

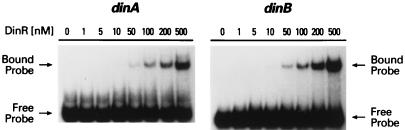

Binding of DinR protein to the two DinR boxes upstream of dinC.

Unlike many din genes, dinC contains two DinR boxes, located close to its promoter. The location of each of these sites makes them potential transcriptional repressor binding sites. (As noted above, for the sake of simplicity, we denoted these sites the −53 box and the −24 box (with respect to their locations near the −35 and −10 promoter elements, respectively) (Fig. 1). Indeed, DNase I and hydroxy radical footprinting experiments have shown that both sites are apparently protected in the presence of DinR (16). The relative affinity of DinR for each DinR box is, however, unknown. To determine the affinity of DinR for each of these sites, DNA mobility gel shift assays were performed with a probe containing only the −53 site, a probe containing only the −24 site, and a probe that contained both the −53 and the −24 sites (Fig. 4A). Experiments revealed that under these assay conditions, DinR binds specifically to each of the three probes (Fig. 4B). Visual inspection of the shifted complexes suggests, however, that there is no significant difference in the affinity for one probe over another. With the probe containing both DinR boxes, there was, however, a second, larger shifted complex detectable at higher concentrations of DinR. We suggest, therefore, that each DinR box serves equally well as a potential binding site but that at higher cellular concentrations there is a greater likelihood of DinR occupancy at both sites.

FIG. 4.

Binding of DinR to the two DinR boxes located upstream of dinC. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of dinC. The two previously identified Cheo boxes are indicated in bold-faced type, and the positions of the three probes used in the in vitro binding studies are indicated below the sequence as P1 (−24 DinR box), P2 (−53 DinR box), and P3 (both DinR boxes). (B) The individually radiolabeled fragments (P1, P2, or P3; 3.0 ng or ∼3.4 nM) were incubated with various concentrations of DinR (nanomolar monomer) as indicated at the top of each lane. Reactions were performed at room temperature for 25 min. Protein-DNA complexes were separated in native polyacrylamide gels (5% acrylamide) and visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

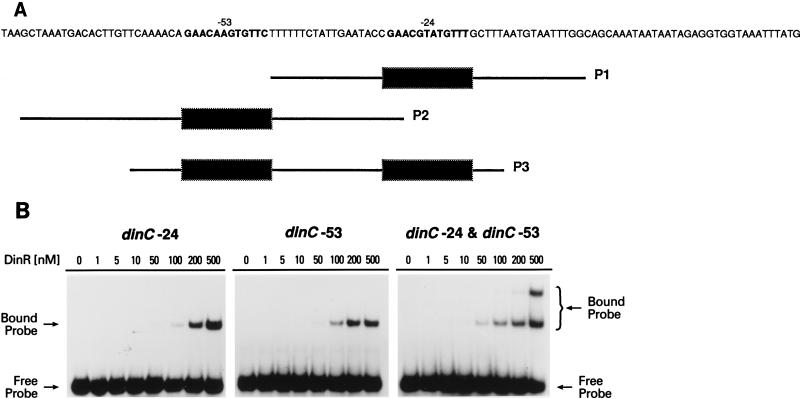

Self-regulation of dinR.

E. coli LexA not only serves as the repressor of a number of unlinked genes in the SOS regulon but also acts as a negative regulator of its own synthesis. We presume, therefore, that like LexA, DinR regulates its own expression. Indeed, gel mobility shift assays with crude cell extracts suggest that this may be the case (5). Although dinR contains three potential binding sites, Haijema et al. have demonstrated that the DinR box, which we denote the −104 box, apparently plays no role in regulating DinR expression (5). The two remaining sites are located at −67 and −39, respectively (Fig. 1 and 5A). These sites have identical core Cheo box sequences and differ from each other only in the N4 region. More importantly, however, they diverge from the consensus sequence, having a 3′ T instead of C (GTTC→GTTT). Thus, we were interested in determining if DinR bound preferentially to one site or equally well to both sites (as is the case for the two dinC DinR boxes). Indeed, the DNA mobility shift assays revealed that DinR binds specifically to all three probes (Fig. 5B), and analysis of the shifted complexes revealed that the affinities of DinR for the −39 and the −67 binding sites are qualitatively similar. As in the case of dinC, however, a second shifted complex is clearly detectable when DinR is incubated with the probe containing both putative binding sites, suggesting that both DinR binding sites can be occupied if there is enough DinR.

FIG. 5.

Binding of DinR to the two DinR boxes located upstream of dinR. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of dinR. The two previously identified Cheo boxes are indicated in bold-faced type, and the positions of the three probes used in the in vitro binding studies are indicated below the sequence as P1 (−39 DinR box), P2 (−67 DinR box), and P3 (both DinR boxes). (B) The individually radiolabeled fragments (P1, P2, or P3; 3.0 ng or ∼3.4 nM) were incubated with various concentrations of DinR (nanomolar monomer) as indicated at the top of each lane. Reactions were performed at room temperature for 25 min. Protein-DNA complexes were separated in native polyacrylamide gels (6% acrylamide) and visualized by exposure to X-ray film.

Detailed molecular analysis of the DinR box located upstream of recA.

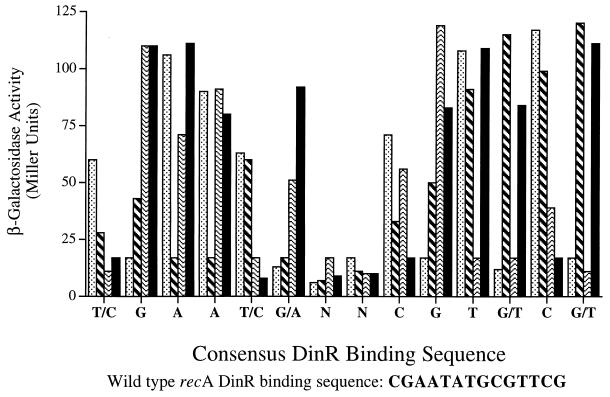

Based upon previous studies (2, 4, 16, 17, 19, 27), DinR or a DinR-like protein unequivocally recognizes and binds to specific sequences located upstream of a number of din genes. In the case of B. subtilis recA, this site is located upstream of the −35 promoter element (approximately at −51) (Fig. 1). By performing detailed mutational studies on this DinR binding site, we have been able to determine which of the bases within the formerly identified Cheo box are important for regulated expression of RecA (Fig. 6). As expected, certain base changes within the core Cheo box resulted in increased basal expression of recA-lacZ transcription in the absence of exogenous DNA damage. It seems very unlikely that these changes affect promoter activity per se, given the location of the DinR box upstream of the −35 region, and we interpret the data as reflecting specific changes in operator affinities. In general, lowest expression was achieved when the sequence matched the consensus Cheo box (2). In some instances, changes in the sequence resulted in constitutive expression (i.e., the most-5′ G of the Cheo box to either A, T, or C), while certain other changes were accommodated (i.e., the C→T transition in the 5′ GAAC side of the Cheo box) (Fig. 6). Interestingly, substitutions in the two outermost nucleotides in the N4 region also appear to affect recA-lacZ expression, whereas those in the very middle of this region appear to have little effect (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Expression of B. subtilis recA-lacZ

transcriptional fusions. The effects of single base pair changes within

the B. subtilis recA DinR box were determined by

quantitating β-galactosidase activities generated from

recA-lacZ transcriptional fusions expressed in B.

subtilis. The histogram represents the level of β-galactosidase

activity of each individual mutant construct. The effects of

substitutions at each nucleotide in the DinR box were analyzed and are

depicted as follows: G, ░⃞; A,  ; T,

; T,

; C, ▪. The consensus sequence

that resulted in equal to or less than 17 Miller units of

β-galactosidase activity from the recA-lacZ fusion is

given below the histogram. For comparison, the wild-type sequence for

the recA DinR box is also listed.

; C, ▪. The consensus sequence

that resulted in equal to or less than 17 Miller units of

β-galactosidase activity from the recA-lacZ fusion is

given below the histogram. For comparison, the wild-type sequence for

the recA DinR box is also listed.

As part of these studies, we have analyzed the effects of changes in the 5′ and 3′ bases that flank the Cheo box. Interestingly, while changes in the 5′ cytosine to thymine or adenine had very little effect on expression of the recA-lacZ fusion, a change to a guanine resulted in constitutively high levels of expression (Fig. 6). Likewise, changes from the 3′ guanine to thymine had little effect, while those to adenine or cytosine resulted in constitutive expression. Assuming that a β-galactosidase level of 17 Miller units or lower represents the baseline for recA-lacZ expression from the various mutant DinR boxes, the lowest level of expression (and therefore the tightest DinR binding) appears to be attained when the DinR box is 5′-T/CGAAT/CG/ANNCGTG/TCG/T-3′ (where the previously described consensus Cheo box is underlined) (Fig. 6). This sequence fits remarkably well with the newly derived consensus DinR binding site (see below).

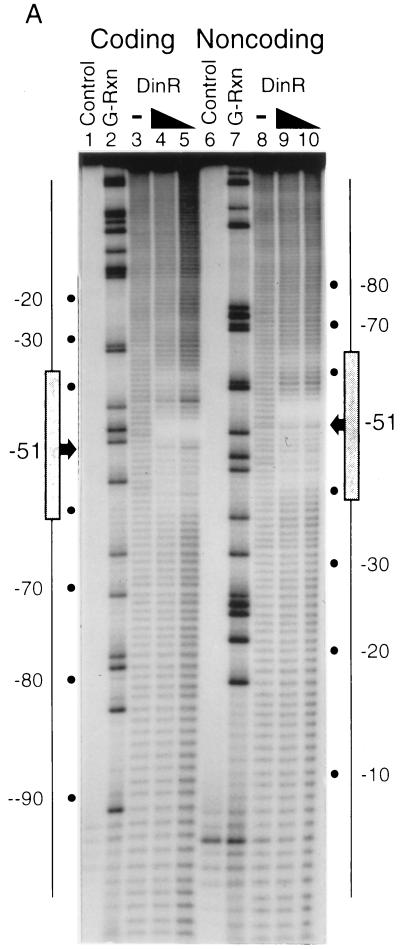

Hydroxyl radical footprinting of the B. subtilis recA and dinR DinR boxes.

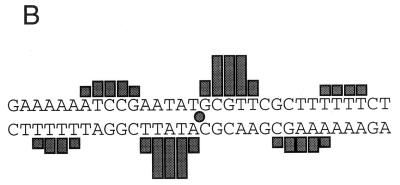

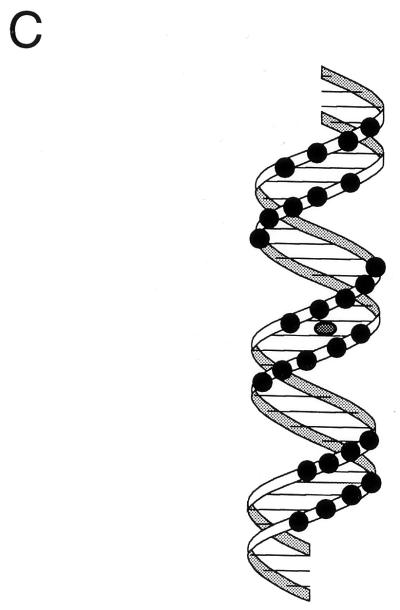

Given that we and others (4, 27) have demonstrated that nucleotide changes in the core Cheo box abolish binding of DinR or a DinR-like protein, as measured by gel mobility shift assays, the assumption that the binding occurs at the Cheo box seems more than reasonable. Unfortunately, the results of gel mobility shift assays can often be misleading when binding is weak (see reference 1 for a detailed discussion). As a consequence, binding often needs to be analyzed by alternative methods, such as DNA-footprint analysis. Indeed, Miller et al. (16) and Durbach et al. (4) have used such an approach to show that the core Cheo box is protected from DNase I and hydroxyl radical cleavage. Nevertheless, we were encouraged to perform additional footprint analyses to firmly establish that DinR does bind to the DinR box proposed in this study. To this end, we performed hydroxyl radical protection assays in the presence and absence of DinR with the B. subtilis recA and dinR promoter/operator sequences (Fig. 7 and 8). As noted previously, DinR binds specifically to the recA promoter/operator region to form a single major protein DNA species as evidenced by nondenaturing gel mobility shift (27). When this species is analyzed by hydroxyl radical footprinting, a pattern of protection is observed which is consistent with a single high-affinity binding site. A single region of protection is observed on each DNA strand. Within each region, a stretch of 3 to 4 bases is most strongly protected by DinR. These strongly protected stretches are each flanked by two regions of weaker protection (Fig. 7A). When the protection pattern is plotted on a linear representation of the recA sequence (Fig. 7B), it is clear that these stretches of protection are separated by about 10 bp and staggered on opposite strands by about 2 to 4 bp, with a total of 30 to 31 bp being protected from cleavage. These results indicate a cross-groove pattern of protection most likely caused by a protein lying along one side of the DNA helix. In support of this interpretation, a plot of protected positions on a three-dimensional representation of the DNA double helix reveals that all protected sites lie along one face of the DNA (Fig. 7C), exactly as has been found for footprints of other bacterial repressor-DNA complexes (6). Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the center of the footprint coincides exactly with the center of the proposed DinR box (CGAATATGCGTTCG) found at this position.

FIG. 7.

Footprinting analysis of DinR bound to the recA operator. (A) The coding and noncoding strands of a radiolabeled recA promoter fragment were incubated with increasing concentrations of purified DinR and subjected to hydroxyl radical cleavage (lanes 4 and 5 and 9 and 10, respectively). Labeled DNA was also cleaved in the absence of DinR (lanes 3 and 8). Each experiment was run alongside naked DNA (Control) and a G sequencing reaction (G-Rxn). The boxed regions denote the location of the DinR box on each strand. The −51 site is representative of the most intense region of protection as well as the center of each DinR box. (B) Nucleotide sequence of the recA operator and regions protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage. The sizes of the bars correspond to the intensities of protection. The center of the protected region is represented by a shaded circle that corresponds to the center of the DinR box. (C) Three-dimensional representation of the bases within the recA operator that are protected by DinR during hydroxyl radical cleavage, indicating that the protected sites lie on one face of the DNA.

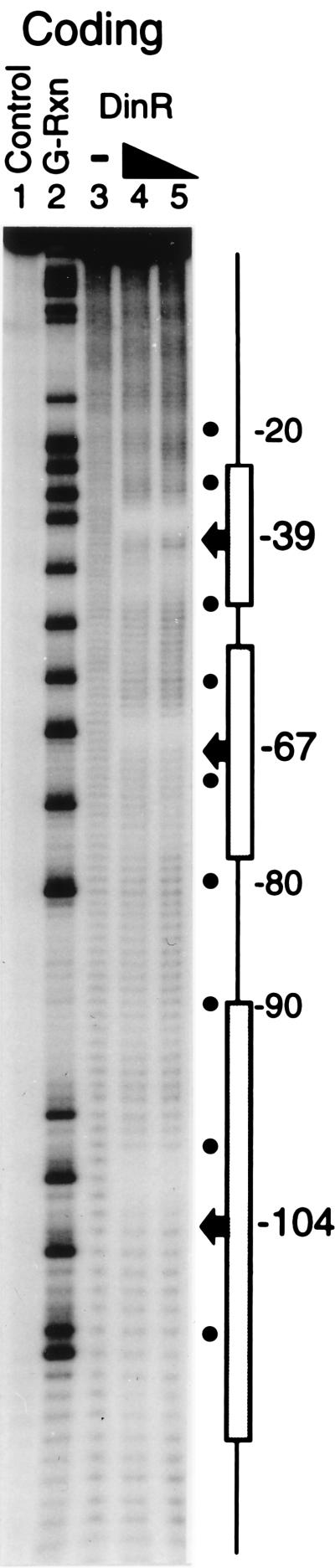

FIG. 8.

Footprinting analysis of DinR bound to the dinR operator. The coding strand of a radiolabeled dinR promoter fragment was incubated with increasing concentrations of purified DinR and subjected to hydroxyl radical cleavage (lanes 4 and 5). Labeled DNA was also cleaved in the absence of DinR (lane 3). The experiment was run alongside naked DNA (Control) and a G sequencing reaction (G-Rxn). The boxed regions denote the locations of the DinR boxes. The −39, −67, and −104 sites are representative of the most intense regions of protection as well as the centers of the respective DinR boxes.

The nondenaturing gel mobility shift assay suggests that DinR apparently binds to the dinR promoter/operator to form two major protein-DNA species (Fig. 5). Presumably, the faster-migrating band contains only one DinR-DNA complex, whereas the slower-migrating band contains two. Interestingly, footprints of the larger probe containing all three potential DinR binding sites (−39, −67, and −104; Fig. 1) revealed that when fully loaded, DinR apparently protects all three regions. Indeed, these regions are most clearly demarcated by the most intense area of protection, found in the center of the footprint pattern (Fig. 8). When cross-strand offset is corrected for (see above), the centers of these three regions of protection can be identified. In concordance with the recA footprint, the regions of protection coincide exactly with the centers of the predicted DinR box elements within the dinR promoter. As noted, we find that with the larger probe used in the footprinting assay, the −104 DinR box does bind DinR, even though it has previously been reported to play no role in regulating dinR (5).

Determination of the oligomeric state of DinR.

Sequence analysis of the DinR box shows two regions of dyad symmetry. This configuration appears to represent two potential half sites that could theoretically each be bound by a DinR monomer. LexA has previously been shown to exist primarily as a monomer in solution (22, 23) and dimerizes upon binding to the SOS box (8).

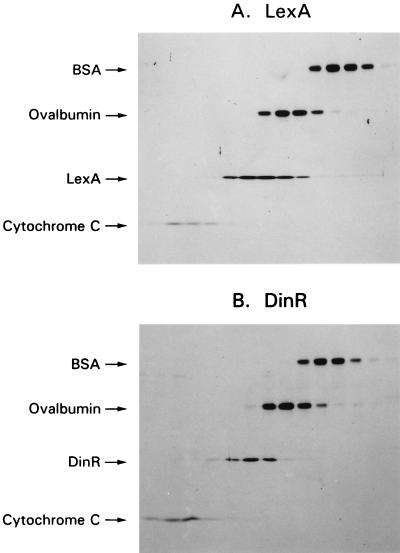

Since LexA and DinR are functionally analogous (16, 27), we were interested in determining the oligomeric state of DinR in solution and bound to target DNA. The solution state was determined by comparison of its sedimentation on a glycerol gradient to that of the E. coli LexA protein and to known protein standards. Under these assay conditions, LexA and DinR sediment virtually identically (Fig. 9). Unlike sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, which largely separates proteins based upon the length of the polypeptide, glycerol gradient sedimentation is a measure of molecular size rather than mass and assumes that the unknown proteins (in these experiments, LexA or DinR) occupy the same shape and specific volume as the known standards. This does not appear to be a valid assumption in the case of LexA and DinR, as the observed size of both proteins was larger (∼40 kDa) than that predicted for a LexA or DinR monomer (∼23 kDa). Based upon its sedimentation, however, which was identical to that of LexA (22, 23), we conclude that DinR exists predominantly as a monomer in solution.

FIG. 9.

Determination of the oligomeric state of DinR in solution. A mixture of proteins containing DinR or LexA and standards was sedimented on a 5 to 30% glycerol gradient. Fractions (100 μl each) were collected, and proteins were separated by electrophoresis on 9 to 19% gradient polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were visualized by silver staining the gels. Every other fraction is shown sequentially, starting with the top fraction (more slowly sedimenting, smaller proteins) at the far left. (A) BSA (5 μg), ovalbumin (5 μg), LexA (5 μg), and cytochrome c (2 μg). (B) BSA (5 μg), ovalbumin (5 μg), DinR (5 μg), and cytochrome c (2 μg). Since LexA and DinR sediment identically, we assume that DinR, like LexA, is predominantly a monomer in solution.

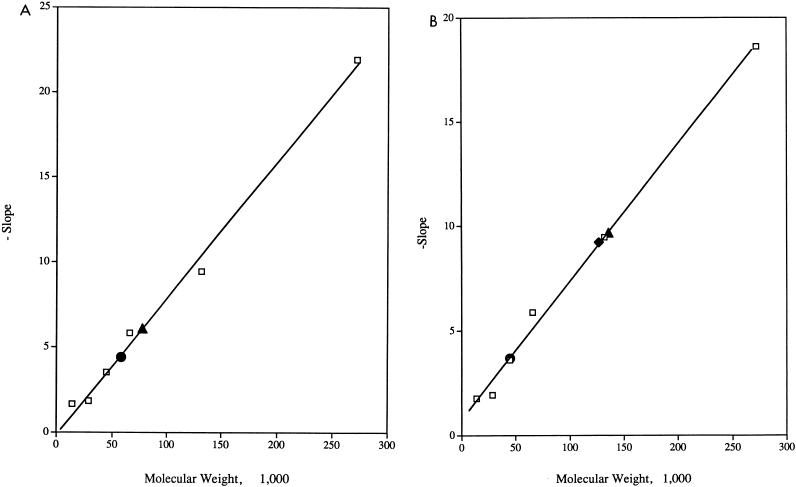

To determine if DinR binds to target DNA as a monomer, dimer, or higher-order oligomer, we used the previously described method of Orchard and May (18) (Fig. 10). Although it is possible to use the theoretical molecular masses of free DNA and DinR protein in these calculations, as noted above, under nondenaturing conditions in which proteins are separated by molecular size, conformation, and charge, the predicted value does not always match that obtained experimentally. As a consequence, we determined empirically the apparent molecular masses of the following complexes: free DNA, DinR monomer, DinR dimer, DinR-dinR, and DinR-recA (Fig. 10). The molecular mass of the DinR-dinR complex was found to be ∼127 kDa, and the molecular mass of the DinR-recA complex was ∼136 kDa. The molecular mass of the DNA, as determined empirically was ∼48 kDa. Thus, after subtracting the molecular mass of the DNA from the DNA-protein complexes, we found that the molecular masses of DinR bound to dinR and to recA are ∼79 kDa and ∼88 kDa, respectively. As noted above, DinR has a predicted molecular mass of ∼23 kDa. In our gel electrophoresis assay, however, the monomeric weight of DinR was found to be ∼60 kDa, and that of the trace amounts of dimeric DinR that were detectable was ∼77 kDa. The difference in these values from those that were predicted presumably arises through the unique electrostatic and structural characteristics of DinR. Thus, the closest fit to the estimated mass of the protein bound to DNA (∼79 to 88 kDa) is that of the empirically determined dimeric DinR protein (∼77 kDa). Based upon these observations, we therefore conclude that DinR, like LexA (8), binds to its target sequence as a dimer.

FIG. 10.

Determination of the oligomeric state and molecular weight of DinR bound to the dinR and recA operators. The retardation coefficient (Kr) of each protein standard was plotted against the molecular weight of the protein to generate the standard curve. The standard curve and the Krs for DinR (A) and the DinR-DNA complexes (B) were used to determine their respective molecular weights. (A) Molecular weight standards: urease trimer, BSA dimer, BSA monomer, ovalbumin, carbonic anhydrase, and α-lactalbumin (□); DinR monomer (•); and DinR dimer (▴). (B) Molecular weight standards: urease trimer, BSA dimer, BSA monomer, ovalbumin, carbonic anhydrase, and α-lactalbumin (□); DNA probe, (•); DinR-dinR (⧫); and DinR-recA (▴). Based upon these observations, we conclude that DinR binds to its operator sequence in a dimeric state (see Results for detailed description of calculations).

DISCUSSION

A new consensus binding site for DinR.

Based upon the combined transcriptional fusion studies, gel mobility shift assays, and hydroxyl radical footprinting, we have derived a new consensus binding site for DinR. Upon reanalysis of the previously identified B. subtilis din genes and those of (presumably damage inducible) recA and lexA/dinR from a variety of gram-positive bacterial species, we find that the 5′ residue of the DinR box is generally cytosine and the 3′ residue is generally guanine (Table 1). In addition, the N4 region does not appear to accommodate all nucleotides and retain equal DinR binding efficiency (Fig. 6) (4, 27). Using such an approach, we derived a consensus DinR binding site of 5′-CGAACRNRYGTTCG-3′. Footprint analysis of several din genes reveals that this sequence is centrally located within a DNA region of 31 bp that is protected by DinR from hydroxyl radical cleavage (Fig. 7 and 8) (4), definitive evidence that this sequence is the one that is recognized and bound by DinR. Furthermore, we found that like E. coli LexA (8, 22, 23, 25), DinR is predominantly monomeric in solution but binds to its target DNA as a dimer (Fig. 10), presumably because each monomer binds cooperatively to one half site.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of putative DinR boxes from the din genes of B. subtilis and the genes of several gram-positive bacteria

| Organism | Genea | DinR binding siteb | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | recA (−51) | CGAATATGCGTTCG* | U56238 |

| dinA | CGAACTTTAGTTCG* | M64048 | |

| dinB | AGAACTCATGTTCG* | M64049 | |

| dinC (−24) | CGAACGTATGTTTG* | M64050 | |

| dinC (−53) | AGAACAAGTGTTCG* | ||

| dinR (−39) | CGAACCTATGTTTG* | M64684 | |

| dinR (−67) | CGAACAAACGTTTC* | ||

| dinR (−104) | GGAATGTTTGTTCG* | ||

| Bacteroides fragilis | recA (−20) | CGAATTAAACTTTG | M63029 |

| recA (−107) | CGAACGGATCATCG | ||

| Clostridium perfringens | recA | AGAACTTATGTTCG | U61497 |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | recA | CGTAGGAATTTTCG | U14965 |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | recA | AGAATGGTCGTTAG | U30387 |

| Deinococcus radiodurans | recA | CGATCCTGCGTAAG | U01876 |

| Mycobacterium leprae | recA | CGAACAGATGTTCG | X73822 |

| Mycobacterium smegmatis | recA | CGAACAGGTGTTCG* | X99208 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | recA | CGAACAGGTGTTCG* | X58485 |

| lexA | CGAACACATGTTTG* | X91407 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | recA | CGAACAAATATTCG | L25893 |

| Streptococcus mutans | recA | CGAACATGCCCTTG | M81468 |

| Streptomyces lividans | recA | CGAACATCCATTCT | X76076 |

| Thermotoga maritima | recA | CGAATGTCAGTTTG | L23425 |

The location of the DinR box with respect to identified promoter elements is noted in parentheses.

The consensus DinR binding site, CGAACRNRYGTTCG, is defined as occurring in at least 70% of the sequences analyzed. With standard nomenclature, R = G or A and Y = C or T. The most-5′ and most-3′ nucleotides of the DinR box are in bold-faced type, while those of the previously identified Cheo box are underlined. Sequences with an asterisk denote sites that have been experimentally shown to physically bind DinR (or a DinR-like protein): B. subtilis recA (16, 27), dinA (Fig. 2), dinB (Fig. 2; [16]), dinC (Fig. 3; [16]), and dinR (Fig. 4; [5]); M. smegmatis recA (4, 19); M. tuberculosis recA (19) and lexA (17). The consensus sequence of the derived DinR box is 5′-CGAACRNRYGTTCG-3′.

Obviously, there are minor differences in the DinR box sequence from one gene to another. These slight deviations from the consensus are also seen in the SOS box of E. coli and are deemed essential for the differential regulation of SOS genes, allowing the cell to provide a graded response to DNA damage. We expected that deviations from the consensus DinR box would have direct effects on the affinity of DinR for each site, but as evidenced by the data from the present study, this is not always the case. For example, based upon the transcriptional studies with recA, we would expect a cytosine at the very 3′ end of the newly defined DinR box to lead to a complete loss of DinR binding. Such changes are found in the −67 DinR box of dinR (Fig. 1); yet, paradoxically, this sequence still binds DinR. Thus, efficient binding at any site is most likely determined by the sequence context of the entire DinR box. In naturally occurring DinR boxes, compensatory mutations may have arisen so that unregulated expression of (a potentially toxic) protein does not occur. We suggest, therefore, that the consensus sequence of the DinR box should be used as an indicator of potential DinR binding but that definitive in vitro studies (gel mobility shift assay and footprinting) should be performed on each site before any site is assumed to be bound by DinR.

The binding site for DinR was originally proposed to be a region of 12 bp with dyad symmetry (5′-GAAC-N4-GTTC-3′). The spacing of these two half sites is much closer than that of the E. coli SOS box [5′-CTGT-(AT)4-ACAG-3′]. The data presented in this paper suggests, however, that the sequence recognized by DinR is at least 2 bp larger than that previously predicted. The new DinR box (5′-CGAACRNRYGTTCG-3′) still retains dyad symmetry, but we find that mutations all along the binding element have some effect on binding affinity. Clearly, unambiguous delineation of the nucleotides within each half site which make interactions with the DinR monomers sequence specific will require classical structural characterization. However, the mutation analysis combined with footprinting data and analogy to other repressor/operator structures suggests that the outer 4 to 5 bp make interactions with DinR sequence specific, while the inner 4 bp act as a spacer element. Mutations in the outer 5 bp of the operator have the greatest effect on affinity, while those in the central 4-bp spacer element have a qualitatively weaker effect on DinR binding. The hydroxyl radical footprinting results indicate that the physical center of the protein-DNA complex coincides exactly with the center of the genetically defined DinR box (Fig. 7A and B). Furthermore, the footprinting data reveals that the outer 5 bp within this element are oriented such that the major groove edge directly faces the DinR protein, while the minor groove of the 4-bp spacer element is oriented toward the protein in the center of the complex (Fig. 7C). In addition, X-ray and biochemical analyses of other repressor/operator complexes show that changes in uncontacted spacer elements can have substantial effects on operator affinity. This effect is due to subtle sequence-dependent changes in DNA structure and consequently to the relative orientation and presentation of contacted residues at opposite ends of the element (11, 12).

These studies, together with previously published studies (16, 27), clearly demonstrate that the E. coli LexA and B. subtilis DinR proteins are both structurally and functionally related. The major difference between the proteins is the site to which they specifically bind to DNA. Nuclear magnetic resonance-based studies have shown that the Ser39, Asn41, Ala42, Glu44, and Glu45 residues of LexA interact with the CTGT half site (9). With the exception of Ser39, these residues are not conserved in the B. subtilis DinR protein or in related gram-positive DinR-like proteins (10, 27), so perhaps the difference in the DNA binding site is not too surprising. The question of which DinR residues make contact with its DNA binding site will undoubtedly be resolved by the eventual X-ray- or nuclear magnetic resonance-derived analysis of DinR structure.

Affinity of DinR for each DinR box.

One interesting feature of this study is our observation that all the DinR operator sequences appear to bind DinR protein with roughly equal affinities. A simple explanation is that the gel mobility shift assay used to quantitate binding is not sensitive enough to identify possible differences (1). Indeed, more quantitative experiments currently in progress will allow us to determine the dissociation constant of DinR for each DinR box. A finding of an equal affinity of DinR for each DinR box would contrast dramatically with the finding that E. coli uses differential binding of LexA to its SOS box to regulate damage-inducible gene expression. Unlike E. coli, however, in which SOS regulation appears to be straightforward, B. subtilis has at least four different modes of SOS induction (28), and additional factors, such as activator proteins (21), seem likely to provide the ancillary functions to induce the regulon under various environmental and developmental stimuli. The availability of an inducible SOS response is important and has been conserved in both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms, but the process of evolution has allowed the development of divergent regulatory mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gerry Barcak for E. coli GBE180, John Little for the highly purified E. coli LexA protein, and Rick Wolf and Phil Farabaugh for their comments on the manuscript.

This research was partially supported by NSF grant MCB-9219436 to R.E.Y., Public Health Service grant RO1GM52426 to J. J. Hayes, and University of Rochester Cancer Center training grant no. CA09363D-16A1 to D.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carey J. Gel retardation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08010-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheo D L, Bayles K W, Yasbin R E. Cloning and characterization of DNA damage-inducible promoter regions from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1696–1703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1696-1703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheo D L, Bayles K W, Yasbin R E. Molecular characterization of regulatory elements controlling expression of the Bacillus subtilis recA+gene. Biochimie. 1992;74:755–762. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(92)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durbach S I, Andersen S J, Mizrahi V. SOS induction in mycobacteria: analysis of the DNA-binding activity of a LexA-like repressor and its role in DNA damage induction of the recA gene from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:643–653. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5731934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haijema B J, van Sinderen D, Winterling K, Kooistra J, Venema G, Hamoen L W. Regulated expression of the dinR and recA genes during competence development and SOS induction in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes J J, Tullius T D. The missing nucleoside experiment: a new technique to study recognition of DNA by protein. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9521–9527. doi: 10.1021/bi00450a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard-Flanders, P., and R. P. Boyce. 1966. DNA repair and genetic recombination: studies on mutants of Escherichia coli defective in these processes. Radiat. Res. 6(Suppl.):156–184. [PubMed]

- 8.Kim B, Little J W. Dimerization of a specific DNA-binding protein on the DNA. Science. 1992;255:203–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1553548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knegtel R M A, Fogh R H, Ottleben G, Rüterjans H, Dumoulin P, Schnarr M, Boelens R, Kaptein R. A model for the LexA repressor DNA complex. Proteins. 1995;21:226–236. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koch W H, Woodgate R. The SOS response. In: Nickoloff J A, Hoekstra M F, editors. DNA damage and repair: DNA repair in prokaryotes and lower eukaryotes. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koudelka G B, Harbury P, Harrison S C, Ptashne M. DNA twisting and the affinity of bacteriophage 434 operator for bacteriophage 434 repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4633–4637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koudelka G B, Harrison S C, Ptashne M. Effect of non-contacted bases on the affinity of 434 operator for 434 repressor and Cro. Nature. 1987;326:886–888. doi: 10.1038/326886a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis L K, Harlow G R, Gregg-Jolly L A, Mount D W. Identification of high affinity binding sites for LexA which define new DNA damage-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:507–523. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Little J W. Autodigestion of LexA and phage repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller M C, Resnick J B, Smith B T, Lovett C M., Jr The Bacillus subtilis dinR gene codes for the analogue of Escherichia coliLexA. Purification and characterization of the DinR protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33502–33508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Movahedzadeh F, Colston M J, Davis E O. Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis LexA: recognition of a Cheo (Bacillus-type SOS) box. Microbiology. 1997;143:929–936. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orchard K, May G E. An EMSA-based method for determining the molecular weight of a protein-DNA complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3335–3336. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.14.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papavinasasundaram K G, Movahedzadeh F, Keer J T, Stoker N G, Colston M J, Davis E O. Mycobacterial recA is cotranscribed with a potential regulatory gene called recX. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:141–153. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3441697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymond-Denise A, Guillen N. Identification of dinR, a DNA damage-inducible regulator gene of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7084–7091. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7084-7091.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raymond-Denise A, Guillen N. Expression of the Bacillus subtilis dinR and recAgenes after DNA damage and during competence. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3171–3176. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3171-3176.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schnarr M, Granger-Schnarr M, Hurstel S, Pouyet J. The carboxy-terminal domain of the LexA repressor oligomerises essentially as the entire protein. FEBS Lett. 1988;234:56–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnarr M, Pouyet J, Granger-Schnarr M, Daune M. Large-scale purification, oligomerization equilibria, and specific interaction of the LexA repressor of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1985;24:2812–2818. doi: 10.1021/bi00332a032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J. Ph.D. thesis. Baltimore County: University of Maryland; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thliveris A T, Little J W, Mount D W. Repression of the E. coli recAgene requires at least two LexA protein monomers. Biochimie. 1991;73:449–456. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90112-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wertman K F, Mount D W. Nucleotide sequence binding specificity of the LexA repressor of Escherichia coliK-12. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:376–384. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.1.376-384.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winterling K W, Levine A S, Yasbin R E, Woodgate R. Characterization of DinR, the Bacillus subtilisSOS repressor. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1698–1703. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1698-1703.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yasbin R E, Cheo D L, Bayles K W. Inducible DNA repair and differentiation in Bacillus subtilis: interactions between global regulons. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1263–1270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]