Abstract

Background A physician's effectiveness depends on good communication, and cognitive and technical skills used with wisdom, compassion, and integrity. Attaining the last attributes requires growth in awareness and management of one's feelings, attitudes, beliefs, and life experiences. Yet, little empiric research has been done on physicians' personal growth. Objective To use qualitative methods to understand personal growth in a selected group of medical faculty. Design Case study, using open-ended survey methods to elicit written descriptions of respondents' personal growth experiences. Setting United States and Great Britain. Participants Facilitators, facilitators-in-training, and members of a personal growth interest group of the American Academy on Physician and Patient, chosen because of their interest, knowledge, and experience in the topic area and their accessibility. Measurements Qualitative analysis of submitted stories included initially identifying and sorting themes, placing themes into categories, applying the categories to the database for verification, and verifying findings by independent reviewers. Results Of 64 subjects, 32 returned questionnaires containing 42 stories. Respondents and nonrespondents were not significantly different in age, sex, or specialty. The analysis revealed 3 major processes that promoted personal growth: powerful experiences, helping relationships, and introspection. Usually personal growth stories began with a powerful experience or a helping relationship (or both), proceeded to introspection, and ended in a personal growth outcome. Personal growth outcomes included changes in values, goals, or direction; healthier behaviors; improved connectedness with others; improved sense of self; and increased productivity, energy, or creativity. Conclusions Powerful experiences, helping relationships, and introspection preceded important personal growth. These findings are consistent with theoretic and empiric adult learning literature and could have implications for medical education and practice. They need to be confirmed in other physician populations.

A physician's therapeutic effectiveness requires good communication and technical and cognitive skills used with personal maturity, wisdom, compassion, and integrity. The development of the last 4 qualities requires understanding oneself and one's relations to others.1

Physicians' conscious and unconscious attitudes, beliefs, previous life experiences, emotions, and psychological and cultural background influence their care of patients,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 sometimes detrimentally.1,3,5,6,8,11,12 By being aware of and managing these factors, physicians can better serve the needs of patients1,5,8,12 and of themselves.13,14

Although methods to promote the growth of personal awareness in physicians have been described,1,8,15 we know of no empiric studies that examine the process and outcomes of such personal growth. In this study, we qualitatively analyze stories of personal growth to uncover the process and outcomes of personal growth in a selected group of medical faculty, and to develop an explanatory framework that might be useful to learners, educators, and researchers.

Summary points

Lack of physicians' personal awareness can adversely affect patient care

In this study, the processes involved in growth in personal awareness were powerful experiences, helping relationships, and reflection or introspection

Outcomes of personal growth include changes in values and goals; improved behaviors and relationship; and increased energy, productivity, and creativity

Awareness of these processes of personal growth, if confirmed in other studies, could lead to improvements in medical education and practice

METHODS

Study population

Questionnaires were mailed to facilitators, facilitators-in-training, and members of a personal growth interest group of the American Academy on Physician and Patient (AAPP). These persons have participated in and taught courses in doctor-patient communication for medical faculty and practicing physicians. The courses include personal awareness groups—supportive groups that facilitate participants' reflection on their own feelings, reactions, and background as they relate to meaningful or troublesome professional or personal experiences. This population was chosen because their interest, knowledge, and experience concerning personal growth would enable informed responses to the study questions.

Questionnaire

Data were collected over 12 months in 1994-1995 and involved as many as 4 mailings. Respondents were asked, “Please tell us your [personal growth] story(ies), by describing 1 or more experiences of growth in your own self-awareness (of your personal history, feelings, assumptions, beliefs, or behavioral responses, for example) and how that growth has affected you professionally and personally.” The Institutional Review Board of the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, exempted the study from further review, judging that the study participants were at no significant risk. The survey was confidential, with an option of anonymity.

Data analysis

Stories were transcribed and typed. Five study team members (J A C, R F, D E K, M L, J M S) read each story, recorded their impressions of the meanings and themes reflected by the stories, and underlined text supporting these impressions. They then listed recurrent or important themes and any contradictory data.

The individual themes were categorized by 1 study team member (S M W), then refined and simplified with 2 other team members (J A C, D E K). Further revisions were made following discussion with the entire research team and application of the categories to a subset of stories.

Three team members (J A C, D E K, S M W) reviewed the stories again to explore relationships and sequences among categories. The entire team reached consensus regarding their findings.

Two independent reviewers (a general internal medicine faculty member and a medical student) analyzed each story using the above-derived categories. For each story, they listed important story components not classifiable using these categories, and diagrammed the sequence in which the categories occurred.

RESULTS

Response rate and characteristics of respondents

Forty-two stories of personal growth were returned by 32 of the 64 study subjects. Respondents came from 15 US states (n = 31) and Great Britain (n = 1). Almost all held medical school faculty appointments and were involved in teaching in their home institutions. Demographic characteristics are shown in the table.

Explanatory framework

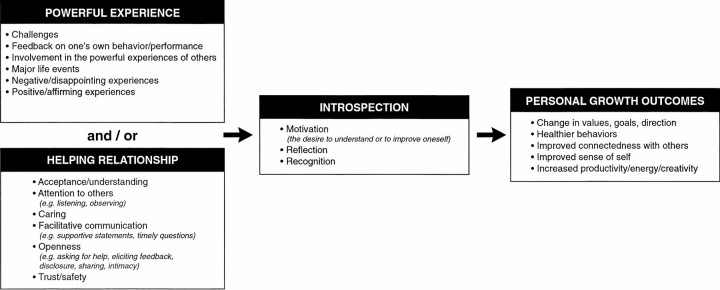

Qualitative analysis revealed personal growth processes of powerful experiences, helping relationships, and introspection and personal growth outcomes, including changes in values, goals, or direction; healthier behaviors; improved connectedness with others; improved sense of self; and increased productivity, energy, or creativity. These are illustrated in the figure (see p 95), together with subcategories for the personal growth processes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents*

| Characteristic | Respondents (n = 32) | Nonrespondents (n = 32) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range), yr | 45.3 (33-71) | 44.6 (31-55) | 0.53 |

| Male sex, no. (%) | 24 (75) | 22 (69) | 0.58 |

| Specialty, no. (%) | 0.78 | ||

| Internal medicine | 22 (69) | 23 (72) | |

| Psychiatry | 3 (9) | 4 (13) | |

| Family medicine | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | |

| Pediatrics | 0 | 2 (6) | |

| Behavioral science | 6 (19) | 2 (6) |

Respondents were compared with nonrespondents using Student's t test for means and χ2 for categoric data. A 2-tailed P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Powerful experiences described experiences that evoked strong feelings in a respondent or affected the respondent's sense of self. Feedback and involvement in the powerful experiences of others, commonly described subcategories of powerful experiences, are illustrated in these story excerpts:

Seven years ago, one of the best friends I ever had developed leukemia. The therapy was unsuccessful, but worse still were the toxic, unpleasant side-effects of treatment.... I am still haunted by the last conversation we had, when she asked why I had not tried to dissuade her from a therapy with poor chances of survival but a high chance of destroying the quality of whatever life she had left.16 [Respondent 46]

As a resident in medicine, I managed the inpatient care of a young man my own age with chronic renal failure.... Since he had no hope of gaining access to renal dialysis (there were virtually no dialysis facilities at that time), we both recognized that he was going to die soon. During 1 of his admissions, he asked me what it was going to be like to die. The directness of his questions came as a complete surprise at a time when I was feeling tired and vulnerable.... I tried to answer his questions, but as I talked, I felt a mounting sense of panic and a powerful urge to bolt off the ward. I was able to sit at his bedside, however, and talk.... [Respondent 24]

Helping relationships described interpersonal interactions that helped respondents and had the characteristics of acceptance, understanding, attention to others (eg, listening, observing), caring, facilitative communication (eg, supportive statements, timely questions), openness (eg, asking for help, eliciting feedback, disclosure, sharing, intimacy), trust, or safety. This example depicts openness, trust, safety, and facilitative communication in a mentoring relationship.

The ongoing supervision I received from several senior faculty focused on my interactions with patients as well as my feelings about my training. I was challenged to think about how my reactions to patients reflected personal issues, but always in a supportive, empathetic manner. I particularly recall a discussion with a mentor after I had missed the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in a patient with chronic back pain and depression. With my mentor's help, I was able to share my strong feelings of guilt and shame, forgive myself for the “mistake,” and learn how to avoid similar mistakes in the future. [Respondent 13]

The next example demonstrates openness and facilitative communication in a supportive group.

I've always had difficulty feeling, expressing, and responding to anger. After saying this during 1 of our personal awareness sessions, the facilitator looked at me and asked me how I might tell him if I were angry at him. I started by saying how I'd feel. He stopped me and asked me how I would tell him if I couldn't use words to do so. I immediately had an image flash in front of my eyes of me walking across the room and hitting him. In that instant, I realized I had no responses to anger between suppression/denial and outright violence. I'd never developed these skills as a child and had done little else to develop them since leaving home. For the remainder of our PA [Personal Awareness] sessions that week, I was able to work on that issue in various ways, using my feelings and responses to events happening in the group, focusing on how I felt when angry and what I did, and asking for feedback from the group about how I came across to them.... [Respondent 16]

Introspection described story components, including motivation (the desire to understand or to improve oneself), reflection, and recognition (eg, of behaviors, defenses, feelings, or the effect of one's personal history).

Reflection, recognition, and motivation are illustrated in these excerpts:

I received feedback on a patient interview that my affect was too upbeat, warm, and “smiley” for the context. In processing this later, it dawned on me that this lady's illness reminded me of an illness I had once had and that my affect was my own way of compensating for the inner fear and anxiety shared by her story. [Respondent 51]

In 1 course, I identified in PA and then later in a skills group that I was acting almost all the time from a deep and compelling need to “take care” of my students. From the feedback I received, I realized that some people experience my care-taking behavior as controlling and limiting... not trusting of their autonomy. From this breakthrough realization, I came to reformulate my values (taking care of others is my life's goal) to a more useful and truthful, genuine set of values based on caring for others, which often means behaving as if others are capable and that I trust them to learn on their own and to take care of their own needs. This meant that I acted less directive and less “motherly.” I feel that this has had major impact on my effectiveness as a teacher and physician. [Respondent 49]

Professionally, I had always had a tough time providing balanced feedback—always easily gave positive feedback, but often “overlooked” corrective incidents and had difficulty presenting corrective incidents even when I “noticed” them. To remedy this, I took several workshops on “giving feedback” and “working with the problem resident.” The result of this superficial “skill development” work was scant at best. I still had great trouble giving balanced feedback. Then I began to address this as more of a PA [personal awareness] issue, not just a skill-building one. I realized that I had trouble with intimacy in general, was more superficial in my relationships than I wanted to be, and had a tough time expressing strong feelings in general—positive as well as negative. [Respondent 23]

Personal growth outcomes included changes in values, goals, or direction (eg, increased freedom in making choices, redefinition of one's values or goals, changes in career); healthier behaviors (eg, increased congruence between feelings and actions, improved management of difficult feelings, letting go of dysfunctional defenses, improved interpersonal skills); improved connectedness with others (eg, decreased isolation and alienation, increased openness, increased helping of others, increased leadership roles); an improved sense of self (eg, improved understanding of self, acceptance of self, acceptance of responsibility for one's own behaviors, problems or issues, self-confidence, internal satisfaction); and increased productivity, energy, or creativity (eg, improved time management, improved decision making, new products such as books or articles, improved teaching).

An improved sense of self and healthier behaviors is illustrated in the continuation of the story about a resident caring for a patient dying of renal failure:

The experience made me realize how powerful my own fear of death was and how much of an impact that fear could have on my relationship with patients. The fear goaded me—and probably still does—to try to understand more about how feelings raised by our medical experiences influence our relationship with patients and how we can use these feelings to grow in our ability to control them. [Respondent 24]

The next example describes improved connectedness with others.

Without question, the most powerful experience of growth in my own personal awareness came with the dissolution of my first marriage.... As a result, I plunged into a several-year quest for personal awareness.... As a result, I got to know myself (and others) a bit better.... Professionally, I am now an incredibly empathic listener for my patients who are distraught over marital (and other) problems. I don't see them as dysfunctional failures but rather as often-capable people doing their best trying to survive [difficult experiences]. [Respondent 48]

This story continuation about the respondent's experience with a friend with leukemia demonstrates improved productivity and creativity and changes in career goals and direction.

I do not know the answer to that question [about why the respondent had not dissuaded the friend from a therapy with a poor chance of survival, but a high chance of diminishing her quality of life], but acknowledgment of her courage and recollection of the physical and mental anguish that she suffered provided the primary impetus for writing [a] book.16

This same respondent expanded on this story:

The experience led me to change research fields entirely and work on the psychosocial aspects of cancer care, looking at such things as quality of life, decision making in cancer, communication, and counseling. [Respondent 46]

Relationships and sequences among categories

An initial review of stories for relationships and sequences among categories revealed that stories usually began with a powerful experience, a helping relationship, or both, proceeded to the stage of introspection, and resulted in a personal growth outcome. More rarely, a powerful experience or helping relationship proceeded directly to a personal growth outcome without introspection, or a helping relationship followed introspection before proceeding to a personal growth outcome. Interactions between categories were sometimes complex. For example, a helping relationship may also have served as a powerful experience (respondent 16); introspection and helping relationships were sometimes inter-related (respondents 13, 16, and 49); introspection was sometimes present more than once in a story (respondent 16).

Independent reviewers confirmed a personal growth outcome as the final step in the sequence in all except 1 and 3 stories, respectively. Introspection was the process component that most commonly preceded a personal growth outcome. The first reviewer diagrammed introspection as the penultimate step in 25 stories, and the second reviewer did so in 30 stories. The figure illustrates the most common sequence of categories in a story.

Explanatory use of the categories

The process and outcome categories were thought by the 2 independent reviewers to describe all and all except 2, respectively, of the 42 stories.

DISCUSSION

This study has produced a description of growth in personal awareness that includes processes (powerful experiences, helping relationships, introspection), outcomes, and the sequence of events leading to growth.

Powerful experiences are common in medicine. In the educational literature, such experiences are seen as beginning sequences of learning that result in new understanding and meaning, termed transformational learning.17 Our data invite us to consider what makes an experience transformational for a given individual. Elder and Caspi describe an “accentuation principle” whereby persons with certain vulnerabilities or predispositions develop personally during times of stress or challenge.18 Caspi and Moffitt reason that when persons are subjected to extraordinary life events, as physicians commonly are, they not only react based on predispositions and established habits, but they also may develop new modes of response.19 Further study is needed to elucidate the individual and cultural factors that influence personal growth.

In the stories reported by our respondents, a powerful experience was almost always accompanied by introspection, a helping relationship, or both, before a personal growth outcome. Helping relationships identified in this study as facilitative communication, caring, acceptance, understanding, openness, and trust correspond in a general way to theories of therapeutic effectiveness in the psychology and counseling literature10,20,21 and most notably to the work of Carl Rogers.7

Introspection was found in almost all stories. Because it was so common and most frequently preceded a personal growth outcome, it seems particularly worthy of further evaluation. Motivation, reflection, and recognition, the components of introspection in our study, correspond to conation, reflection and recognition, respectively, identified by Mezirow as components of the transformational dimensions of adult leaning.17 Others have described cycles of experience followed by reflection as fundamental to education-induced change and growth.22,23 Such findings suggest that educational opportunities for reflection and learning environments that motivate reflection may be important for physicians' personal development.

Whereas others have examined professional socialization and the management of mistakes,24,25,26,27 to our knowledge, this is the first empiric study of the process and outcomes of growth in personal awareness in medical practitioners. At such an early, exploratory, hypothesisgenerating phase of research, a rich understanding of the phenomenon being studied is preferred and is best achieved through qualitative research methods.28,29,30,31 Accepted methods of qualitative research were used: cases (stories) that were elicited from a selected group of practitioners with expertise in the area (purposeful sampling strategy); generation of explanations from the data, rather than the testing of a preconceived theory using the data; independent reviews of the stories by study team members for identification of themes; iterative consensus to create an overall explanatory framework of themes; and reapplication of the explanatory framework to the data by external reviewers for verification.28,29,31,32 The explanatory framework that emerged from the data has coherence, common-sense appeal, and corresponds with theory and research in education and psychology (face validity and triangulation).7,10,17,18,19,20,22

Several limitations apply to these results. The modest response rate may have been due to how personal and time-consuming the inquiry was. Although respondents were similar to nonrespondents in age, sex, and specialty, they may have differed in undertected respects. The study population was chosen as informed experts. However, they shared a common culture and theoretical perspectives, limiting generalizability of the findings. All had participated in or facilitated learning experiences of the AAPP that are derived in part from rogerian methods and focus participants on the relation between their personal and professional lives.33 Six of the 8 investigators and 1 of the 2 external reviewers were also associated with AAPP. Although 2 of the investigators principally involved in data analysis were not associated with AAPP (S M W, J A C) and data analysis methods were used to ensure that our explanatory framework arose from the data and not preconceived theory, the experience, beliefs, and assumptions of researchers can subconsciously influence data interpretation. A different group of researchers from different professional backgrounds or theoretical perspectives might have derived a somewhat different explanatory framework from the same data set. Because the experiences of personal growth that were described occurred in the past, they may have been subject to faulty memories or to distortion or interpretation in the context of the respondents' cultures and personal biases. Because the experiences were respondent-described and retrospective, we cannot confirm that they actually happened as described. Our study method focused our respondents toward major personal growth events and away from small, incremental, or longitudinal growth experiences, which are less likely to be recalled as stories. Both pathways may be important for personal growth.34 Finally, the explanatory framework derived in this study is only a preliminary step toward a comprehensive classification system with mutually exclusive, reliably coded categories usable to describe and compare experiences quantitatively. As in all heuristic studies, additional research that uses varied populations and methods is required to learn whether our model can be generalized to other populations; to learn whether additional models are required to explain these and related phenomena; and to develop more reproducible, generalizable, and comprehensive explanatory systems.

Our preliminary findings may have important implications for medical education. Powerful experiences occur commonly in medicine but may lack optimal conditions for personal growth. To promote practitioner personal growth, medical settings may wish to explore methods to promote introspection, helping relationships, and the acknowledgment of powerful experiences when they occur. In our respondents' experience, personal growth occurred both in naturally occurring conditions and in structured learning contexts. Additional research is necessary to determine optimal conditions for personal growth. Further studies that use varied populations and methods are required to develop empirically derived principles of education and practitioner self-maintenance that promote personal growth and lead to more effective, satisfied, and well-adjusted professionals. In this time of high practitioner burnout, professional dissatisfaction and distress, and public concern about the health profession, we hope this preliminary study will stimulate reflection and research on medical education and practice.

Figure 1.

Processes, outcomes, and typical sequence in stories of personal growth

Acknowledgments

We thank our participants for their written descriptions of important personal growth experiences, which made this study possible. Statistical consultation was provided by Ken Kolodner. Helpful suggestions regarding early drafts of the manuscript were contributed by L Randol Barker, Nicholas H Fiebach, and Philip D Zieve.

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Novack DH, Suchman AL, Clark W, Epstein RM, Najberg E, Kaplan C. Calibrating the physician: personal awareness and effective patient care. Working group on Promoting Physician Personal Awareness, American Academy on Physician and Patient. JAMA 1997;278: 502-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novack DH. Therapeutic aspects of the clinical encounter. J Gen Intern Med 1987;2: 346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein RM, Morse DS, Frankel RM, Frarey L, Anderson K, Beckman HB. Awkward moments in patient-physician communication about HIV risk. Ann Intern Med 1998;128: 435-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geller G, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Holtzman NA. Measuring physicians' tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med Care 1993;31: 989-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorlin R, Zucker HD. Physician's reactions to patients: a key to teaching humanistic medicine. N Engl J Med 1983;308: 1059-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hornblow AR, Kidson MA, Ironside W. Empathic processes: perception by medical students of patients' anxiety and depression. Med Educ 1998;22: 15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers C. The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. J Consult Clin Psychol 1957;21: 95-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RC. Unrecognized responses and feelings of residents and fellows during interviews with patients. J Med Educ 1986;61: 982-984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA 1993;269: 1537-1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truax CB, Wargo DG. Psychotherapeutic encounters that change behavior: for better or for worse. Am J Psychother 1966;20: 499-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarnold PR, Greenberg MS, Nightingale SD. Comparing the resource use of sympathetic and empathetic physicians. Acad Med 1991;66: 709-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RC, Dorsey AM, Lyles JS, Frankel RM. Teaching self-awareness enhances learning about patient-centered interviewing. Acad Med 1999;74: 1242-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quill TE, Williamson PR. Healthy approaches to physician stress. Arch Intern Med 1990;150: 1857-1861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ryff CD, Singer B. Psychological well-being: meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychother Psychosom 1996;65: 14-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novack DH, Epstein RM, Paulsen RH. Toward creating physician healers: fostering medical students' self-awareness, personal growth, and well-being. Acad Med 1999;74: 516-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fallowfield L. The Quality of Life: The Missing Measurement in Health Care. London: Souvenir Press; 1990. The referenced story was published as the preface to this book. Reproduced with permission of the author, who is the copyright holder.

- 17.Mezirow J. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1991.

- 18.Elder GH Jr, Caspi A. Studying lives in a changing society: sociological and personalogical explorations. In: Rabin AI, Zucker RA, Emmons RA, Frank S, eds. Studying Persons and Lives. New York: Springer; 1990: 201-247.

- 19.Caspi A, Moffitt TE. When do individual differences matter? A paradoxical theory of personality coherence. Psychol Inquiry 1993;4: 247-271. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luborsky L, Auerbach AH. The therapeutic relationship in psychodynamic psychotherapy: the research evidence and its meaning for practice. In: Psychiatry Update: American Psychiatric Association Annual Review. Vol 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1985: 550-561. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoeckle JD, Eisenthal S. Psychotherapeutic techniques of physicians and psychotherapies of counselors: uses and guidelines. In: Noble J, ed. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine. St Louis: Mosby; 1996: 1629-1633.

- 22.Schon DA. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1987.

- 23.Westberg J, Jason H. Fostering learners' reflection and self-assessment. Fam Med 1994;26: 278-282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker HS, Geer B, Hughes EC, Strauss AL. Boys in White: Student Culture in Medical School. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1961.

- 25.Bucher R, Stelling JG. Becoming Professional. Beverly Hills, CA & London: Sage Publications; 1977.

- 26.Bosk CL. Forgive and Remember: Managing Medical Failure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1979.

- 27.Page MA. The Unity of Mistakes: A Phenomenological Interpretation of Medical Work. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1988.

- 28.Britten N, Jones R, Murphy E, Stacy R. Qualitative research methods in general practice and primary care. Fam Pract 1995;12: 104-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patton MQ. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990.

- 30.Poses RM, Isen AM. Qualitative research in medicine and health care: questions and controversy. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13: 32-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merriam SB. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1988.

- 32.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1992.

- 33.Lipkin M Jr, Kaplan C, Clark W, Novack D. Teaching medical interviewing: the Lipkin model. In: Lipkin M Jr, Lazare A, Putnum S, eds. The Medical Interview. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1995: 422-435.

- 34.Hay DF, Castle J, Jewett, J. Character development. In: Rutter M, Hay DF, eds. Development Through Life. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1994: 319-349.