Abstract

The Salmonella enterica smpB-nrdE intergenic region contains about 45 kb of DNA that is not present in Escherichia coli. This DNA region was not introduced by a single horizontal transfer event, but was generated by multiple insertions and/or deletions that gave rise to a mosaic structure in this area of the chromosome.

Since diverging from a common ancestor some 100 to 160 million years ago, the gene order on the chromosomes of the genera Salmonella and Escherichia has retained a high degree of conservation (12, 28). The relatedness of their genomes provides a unique opportunity to identify evolutionary changes that occurred after the lineages of the genera Salmonella and Escherichia split, and analysis of these alterations is likely to provide us with some interesting insights into the genomic archaeology of enteric pathogens.

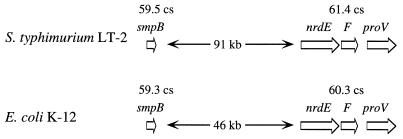

Comparison of the colinear genetic maps of Escherichia coli K-12 and Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (S. typhimurium) revealed 30 so-called loops, genomic regions larger than 0.6 map units (about 28 kb), which are restricted to only one of the two species (31, 32). It was concluded from this work that these differences in genome structure resulted either from acquisition of genetic material by phage- or plasmid-mediated horizontal transfer or from loss of DNA regions by deletion. The largest S. typhimurium-specific loop identified by Riley and coworkers is located at 60 to 61 centisomes in the intergenic region between smpB (6) and nrdE (18). The smpB-nrdE intergenic region of S. typhimurium contains an area of approximately 45 kb which is not present at the corresponding map position of the E. coli chromosome (Fig. 1) (10, 32, 33). Since the sequence for the entire 45-kb DNA region has not been determined, it is unclear whether this S. typhimurium-specific loop is contiguous or rather consists of noncontiguous insertions. It can be estimated from the size of the S. typhimurium loop in the smpB-nrdE intergenic region (roughly 1% of the genome) that it has the capacity to contain about 40 genes, some or all of which may determine properties that distinguish this organism from E. coli. To date, three phenotypic characteristics encoded by genes located in the smpB-nrdE intergenic region have been described in Salmonella serotypes: (i) expression of phase 2 (H2) flagellin, the structural subunit of which is encoded by fljB (16, 42); (ii) uptake of tricarboxylates via a periplasmic binding protein-dependent transport system encoded by the tctCBA operon (40, 41); and (iii) utilization of catecholate-type siderophores via IroN, an outer membrane receptor encoded by a gene located in the iroA locus (7, 8). In addition to the essential role of the fljB gene product for serotyping (21), some of the genes located in the smpB-nrdE intergenic region have proven to be valuable tools for PCR detection of Salmonella serotypes (5, 13, 39). Thus, tracing the evolutionary origin of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region is of interest for both the comprehension of bacterial speciation and the development and evaluation of methods to differentiate Salmonella serotypes from closely related organisms.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the smpB-nrdE intergenic regions of E. coli and S. typhimurium. According to the current physical map of S. typhimurium (upper half), the genes smpB and nrdE are separated by approximately 91 kb (33). In contrast, the distance between smpB and nrdE amounts to only about 46 kb in E. coli (lower half) (10). Genes are indicated by arrows. Map positions in centisomes (cs) of genes in E. coli and S. typhimurium are given above.

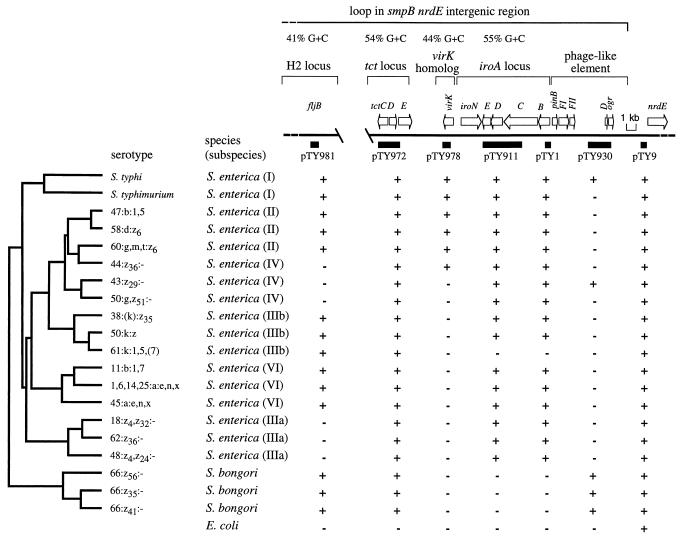

In order to investigate the ancestry of genetic material within the smpB-nrdE intergenic region, we determined its distribution among Salmonella serotypes by using a collection of 20 strains described by Reeves and coworkers (30). This collection represents the genetic diversity within the genus Salmonella and contains isolates of all phylogenetic lineages, including Salmonella bongori and S. enterica subspp. I, II, IIIa, IIIb, IV, and VI. The phylogenetic relatedness of these isolates has been investigated by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (Fig. 2) (30). This information is useful for identification of the branch of the phylogenetic tree at which genetic material may have been acquired or lost (3, 4). It should be mentioned, however, that based on data obtained by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis or comparative sequence analysis, other investigators have reported dendrograms which differ from the phylogenetic tree shown in Fig. 2, in that some S. enterica subspecies are connected through different branch points (11). Thus, this fact should be considered when interpreting DNA hybridization data with only a single dendrogram.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic distribution of genes located in the smpB-nrdE intergenic region. The phylogenetic tree on the left was established by Reeves and coworkers (30). The top of the figure shows a map of the region from S. typhi AJB70. The positions of subcloned DNA fragments used as probes (black bars) and names of the corresponding plasmids (pTY9, pTY930, pTY1, pTY911, pTY978, and pTY972) have been reported previously (8). Results of hybridization with these DNA probes are shown below. +, hybridization signal; −, no hybridization signal. The positions and orientations of genes (tctCDE, iroBCDEN, and nrdE) or open reading frames with homology to genes described for other organisms (virK, pinB, FI, FII, D, and ogr) are indicated by arrows above the map.

Chromosomal DNA of Salmonella serotypes and of E. coli K-12 strain DH5α (14) was prepared as described previously (2) and restricted with EcoRI, and the fragments were separated on a 0.5% agarose gel. The DNA was then transferred onto a nylon membrane, and Southern hybridization was performed under nonstringent conditions as reported earlier (4). The overlapping inserts of the cosmids pTY908 and pTY2117 represent a DNA region of about 30 kb surrounding the iroA locus of S. enterica serotype Typhi (S. typhi) (8). Subclones of these cosmids (pTY972, pTY978, pTY911, pTY1, pTY930, and pTY9) have been reported previously (8) and were used to generate DNA probes specific for different areas of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region (Fig. 2). In addition, an internal fragment of the S. typhimurium fljB gene was PCR amplified with the primers 5′-GACTCCATCCAGGCTGAAATCAC-3′ and 5′-CGGCTTTGCTGGCATTGTAG-3′, the product was cloned into the vector pCR II (TA cloning kit; Invitrogen), and the resulting plasmid (pTY981) was used to generate a DNA probe specific for the H2 flagellar structural gene.

The results of Southern blot analysis are shown in Fig. 2 and are discussed below for each probe, reading from right to left. The probe generated from plasmid pTY9 hybridized with DNA from E. coli and all Salmonella serotypes tested. The nucleotide sequence determined for the insert of plasmid pTY9 showed 99% identity to 615 bp located upstream of the S. typhimurium nrdE gene (18), a region of the chromosome which is also present in E. coli. In contrast, a DNA region located about 4 kb upstream of the nrdE gene (pTY930) hybridized only with DNA from S. typhi, S. bongori, and one serotype of S. enterica subsp. IV. Nucleotide sequences were determined from the ends of the inserts of plasmids pTY930 and pTY941 (GenBank accession no. AF046859). Plasmid pTY941 contains DNA originating from an area located between the inserts of pTY1 and pTY930 (Fig. 2) (8). These nucleotide sequences showed homology to several genes located in the tail synthesis region of bacteriophage P2 and related phages, including FI (36), FII (36), D (19), pinB (37), and ogr (9) (Fig. 2). Since the region of the S. typhi chromosome which displayed homology to phage DNA was much smaller than the P2 genome (32 kb), it can be speculated that it resembles a defective prophage. It is not clear from hybridization analysis whether signals obtained from S. bongori or S. enterica subsp. IV serotypes resemble this defective prophage or originate from a different but closely related bacteriophage. It should be mentioned in this context that an attachment site (atdA) for bacteriophage P14 has been mapped close to nrdE in serotypes of S. enterica subsp. I belonging to serogroup C (S. typhi represents serogroup D) (33). The presence of a defective prophage in S. typhi and the map position of atdA in other Salmonella serotypes suggest that some of the genes located in the smpB-nrdE intergenic region may have been obtained via phage-mediated horizontal transfer.

Each of the S. typhi DNA probes generated from plasmids pTY981, pTY978, pTY911, and pTY1 hybridized with chromosomal DNA from S. typhimurium but not from E. coli, suggesting that the respective DNA fragments originate from the S. typhimurium-specific loop described by Riley and Krawiec (32). However, various areas of this loop differed with respect to their phylogenetic distribution within the genus Salmonella. Thus, this area of the chromosome may have suffered several insertions and/or deletions during divergence of Salmonella serotypes from a common ancestor (Fig. 2). In a previous study, the insert of plasmid pTY1 was shown to be present in all S. enterica strains tested (5). Using the strain collection shown in Fig. 2, plasmid pTY1 hybridized with all isolates of S. enterica, except serotype 61:k:1,5,[7], and this distribution was identical to that recently reported for pTY911 (7). These data imply that the entire iroA locus was likely acquired in a single horizontal transfer event soon after S. enterica branched from the S. bongori lineage (5). However, alternate scenarios that could explain the phylogenetic distribution of the iroA locus (e.g., deletion from S. bongori and E. coli) can currently not be ruled out. Subsequent loss of this DNA region was infrequent and was only detected in S. enterica subsp. IIIb serotype 61:k:1,5,[7]. The G+C content of the 10,837-bp DNA region containing iroBCDE and iroN is 55% (7), close to the overall G+C content of the S. enterica genome, which averages 52%. In contrast, the G+C content of the insert of plasmid pTY978, a DNA region located 1 kb upstream of iroN, averaged only 44% (GenBank accession no. AF029845) (Fig. 2). Previous studies have shown that only 4 of 87 regions sequenced from Salmonella serotypes have G+C contents lower than 45%, and this has been taken as evidence for their acquisition by lateral transfer (15, 35, 38). Since, during evolution, bacteria developed characteristic C+C contents, the atypical base composition of the insert of plasmid pTY978 supports the idea that this DNA region may have been obtained via horizontal transfer (1). Sequence analysis of pTY978 revealed an open reading frame whose deduced amino acid sequence showed 46% identity to VirK of Shigella flexneri (25). In S. flexneri, the virK gene is located on a mobile genetic element, namely the large virulence plasmid, which hints at a possible plasmid-mediated transfer of the virK homolog into the S. enterica genome. To assess the role of this gene in virulence, a SmaI-restricted kanamycin resistance cassette (KIXX; Pharmacia) was introduced into the StuI site located within the open reading frame of the S. typhi virK homolog on plasmid pTY953 (8). The insert of the resulting plasmid (pTY1002) was restricted with XbaI-KpnI and cloned into suicide vector pEP185.2 (20), and the resulting construct (pTY1003) was conjugated into S. typhimurium IR715. An exconjugant which was resistant to kanamycin but sensitive to chloramphenicol (the resistance encoded on pEP185.2) was designated AJB61. Insertion of KIXX into the virK homolog in strain AJB61 was confirmed by Southern blot analysis with a DNA probe derived from plasmid pTY978 (data not shown). The virK homolog was not required for S. typhimurium virulence, because identical oral 50% lethal doses (29) in 6-week-old BALB/c mice were determined for AJB61 and its parent, IR715. A DNA probe specific for the virK homolog (pTY978) hybridized only with isolates of S. enterica subsp. I, II, and IV. Thus, the phylogenetic distribution and the different G+C contents determined for the iroA locus and the virK homolog suggest that both DNA regions have different ancestries.

Sequence analysis (GenBank accession no. AF029846) revealed that the insert of pTY972 contained part of the S. typhi tct locus. A DNA probe derived from plasmid pTY972 hybridized with DNA from all Salmonella serotypes tested (Fig. 2), suggesting that the tct locus was obtained by a lineage ancestral to the genus Salmonella. Alternatively, the tct locus may have been lost by deletion from E. coli after its lineage split from that of the genus Salmonella. The G+C content of 54% determined for the S. typhi tctDE genes resembles the average S. enterica base composition. In contrast, the S. typhimurium hin-fljB region has a G+C content of only 41%, which is indicative of its acquisition by horizontal gene transfer (42). The fljB-specific DNA probe (pTY981) produced yet another hybridization pattern, because it was present in diphasic (expressing flagellar phase H1 and H2) but absent from monophasic (only expressing phase H1) serotypes of S. enterica (Fig. 2). Interestingly, a signal was also obtained with S. bongori, a species which contains only monophasic serotypes. Lack of phase H2 flagellar expression in S. bongori may thus be caused by mechanisms that escape detection by hybridization analysis, such as point mutations or small deletions in fljB. To explain the complex patterns of hybridization obtained with the fljB-specific DNA probe, several mechanisms should be considered. These include deletion events, acquisition of genetic material from other bacterial species by way of horizontal transfer, and/or recombination of horizontally transferred DNA regions among S. enterica subspecies, as proposed previously for the fliC locus (22).

It has been proposed recently that Salmonella pathogenicity islands 1 (SPI 1) and 2 (SPI 2), two large DNA regions that are present in S. enterica but absent from E. coli, were obtained through lateral transfer (17, 23, 24, 26). In S. typhimurium, SPI 1 is a 40-kb DNA region which is inserted between fhlA and mutS, two genes that are adjacent on the E. coli chromosome (24). Results from comparative sequence analysis of seven inv/spa genes located on SPI 1 which encode an invasion-associated type III excretion system support the idea that the entire pathogenicity island was initially acquired through horizontal transfer by a lineage ancestral to the genus Salmonella and subsequently transferred laterally from S. enterica subsp. IV to subsp. VII (11, 23). SPI 2 carries genes encoding a second type III excretion system which is required for growth in cells of the reticuloendothelial system (27, 34). Hybridization analysis revealed that the ssa/spi genes which encode this type III export apparatus are present in all subspecies of S. enterica but are absent from S. bongori and E. coli (17, 26). Evidence for acquisition of SPI 2 by horizontal transfer comes from the atypical G+C content (41%) of genes encoding the type III excretion system and the insertion of this pathogenicity island adjacent to the tRNAVal gene, a DNA region which may facilitate integration of newly acquired genetic material (17). Thus, in the case of SPI 1 and SPI 2, large DNA regions, each containing close to 30 genes that are related functionally, were apparently acquired through a single horizontal transfer event. In contrast to the rather homogeneous composition of pathogenicity islands, hybridization analysis of the smpB-nrdE intergenic region revealed that this area is composed of several DNA regions which differ with regard to their phylogenetic distribution and function (Fig. 2). These DNA regions may have been acquired independently from distinct sources, as suggested by differences in their G+C content. The S. typhi smpB-nrdE intergenic region is therefore apparently a mosaic of at least five DNA regions, each with a different ancestry: the H2 locus, the tct locus, a region encoding a virK homolog, the iroA locus, and a phage-like element. This information is relevant for evaluation of the specificity of PCR detection assays targeting hin (39), tctC (13), or iroB (5).

Acknowledgments

We thank M. W. Reeves for providing bacterial strains, S. Anic and I. Stojiljkovic for help with the sequence analysis, and R. M. Tsolis for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI22933 to F.H. from the National Institutes of Health. Work in A.J.B.’s laboratory is supported by grant AI40124 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoyama K, Haase A M, Reeves P. Evidence for effect of random genetic drift on G+C content after lateral transfer of fucose pathway genes to Escherichia coli. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:829–838. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. New York, N.Y: Wiley & Sons; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäumler A J. The record of horizontal gene transfer in Salmonella. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:318–322. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bäumler A J, Gilde A J, Tsolis R M, van der Velden A W M, Ahmer B M M, Heffron F. Contribution of horizontal gene transfer and deletion events to the development of distinctive patterns of fimbrial operons during evolution of Salmonella serotypes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:317–322. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.317-322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bäumler A J, Heffron F, Reissbrodt R. Rapid detection of Salmonella enterica with primers specific for iroB. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1224–1230. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1224-1230.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bäumler A J, Kusters J G, Stojiljkovic I, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium loci involved in survival within macrophages. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1623–1630. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1623-1630.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bäumler A J, Norris T L, Lasco T, Voigt W, Reissbrodt R, Rabsch W, Heffron F. IroN, a novel outer membrane siderophore receptor characteristic of Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1446–1453. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1446-1453.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bäumler A J, Tsolis R M, van der Velden A W M, Stojiljkovic I, Anic S, Heffron F. Identification of a new iron regulated locus of Salmonella typhi. Gene. 1996;183:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birkeland N K, Lindquist B H. Coliphage P2 late control gene ogr. DNA sequence and product identification. J Mol Biol. 1986;188:487–490. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blattner F R, Plunkett G, Bloch C A, Perna N T, Burland V, Riley M, Colladovides J, Glasner J D, Rode C K, Mayhew G F, Gregor J, Davis N W, Kirkpatrick H A, Goeden M A, Rose D J, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. . (Review.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd E F, Wang F-S, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Molecular genetic relationship of the salmonellae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:804–808. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.804-808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doolittle R F, Feng D, Tsang S, Cho G, Little E. Determining divergence times of the major kingdoms of living organisms with a protein clock. Science. 1996;171:470–477. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doran J L, Collinson S K, Kay C M, Banser P A, Burian J, Munro C K, Lee S H, Somers J M, Todd E C, Kay W W. fimA and tctC based DNA diagnostics for Salmonella. Mol Cell Probes. 1994;8(4):291–310. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1994.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant S G N, Jessee J, Bloom F R, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Groisman E A, Saier M H, Ochman H. Horizontal transfer of a phosphatase gene as evidence for mosaic structure of the Salmonella genome. EMBO J. 1992;11:1309–1316. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05175.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanafusa T, Saito K, Tominaga A, Enomoto M. Nucleotide sequence and regulated expression of the Salmonella fljA gene encoding a repressor of the phase 1 flagellin gene. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;236:260–266. doi: 10.1007/BF00277121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hensel M, Shea J E, Bäumler A J, Gleeson C, Blattner F, Holden D W. Analysis of the boundaries of Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 and the corresponding chromosomal region of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1105–1111. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1105-1111.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan A, Gibert I, Barbé J. Cloning and sequencing of the genes from Salmonella typhimurium encoding a new bacterial ribonucleotide reductase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3420–3427. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3420-3427.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalionis B, Dodd I B, Egan J B. Control of gene expression in the P2-related template coliphages. III. DNA sequence of the major control region of phage 186. J Mol Biol. 1986;191:199–209. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinder S A, Badger J L, Bryant G O, Pepe J C, Miller V L. Cloning of the YenI restriction endonuclease and methyltransferase from Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:8 and construction of a transformable R−M+ mutant. Gene. 1993;136:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90478-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Minor L. Typing of Salmonella species. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1988;7(2):214–218. doi: 10.1007/BF01963091. . (Review.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Nelson K, McWhorter A C, Whittam T S, Selander R K. Recombinational basis of serovar diversity in Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2552–2556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Ochman H, Groisman E A, Boyd E F, Solomon F, Nelson K, Selander R K. Relationship between evolutionary rate and cellular location among the Inv/Spa invasion proteins of Salmonella enterica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7252–7256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills D M, Bajaj V, Lee C A. A 40kb chromosomal fragment encoding Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes is absent from the corresponding region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:749–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakata N, Sasakawa C, Okada N, Tobe T, Fukuda I, Suzuki T, Komatsu K, Yoshikawa M. Identification and characterization of virK, a virulence-associated large plasmid gene essential for intercellular spreading of Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2387–2395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochman H, Groisman E A. Distribution of pathogenicity islands in Salmonella spp. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5410–5412. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5410-5412.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ochman H, Soncini F C, Solomon F, Groisman E A. Identification of a pathogenicity island for Salmonella survival in host cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7800–7804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ochman H, Wilson A C. Evolution in bacteria: evidence for a universal substitution rate in cellular genomes. J Mol Evol. 1987;26:74–86. doi: 10.1007/BF02111283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed L J, Muench H. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reeves M W, Evins G M, Heiba A A, Plikaytis B D, Farmer J J., III Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:313–320. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.2.313-320.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riley M, Anilionis A. Evolution of the bacterial genome. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1976;32:519–560. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.32.100178.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley M, Krawiec S. Genome organization. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 967–981. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanderson K E, Hessel A, Rudd K E. Genetic map of Salmonella typhimurium, edition VIII. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:241–303. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.241-303.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shea J E, Hensel M, Gleeson C, Holden D W. Identification of a virulence locus encoding a second type III secretion system in Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2593–2597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simon M, Zieg J, Silverman M, Mandel G, Doolittle R. Phase variation: evolution of a controlling element. Science. 1980;209:1370–1374. doi: 10.1126/science.6251543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple L M, Forsburg S L, Calendar R, Christie G E. Nucleotide sequence of the genes encoding the major tail sheath and tail tube proteins of bacteriophage P2. Virology. 1991;181:353–358. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90502-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tominaga A, Ikemizu S, Enomoto M. Site-specific genes in three Shigella subgroups and nucleotide sequences of a pinB gene and an invertible B segment from Shigella boydii. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4079–4087. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4079-4087.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verma N, Reeves P. Identification and sequence of rfbS and rfbE, which determine antigenic specificity of group A and group D salmonellae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5694–5701. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5694-5701.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Way J S, Josephson K L, Pillai S D, Abbaszadegan M, Gerba C P, Pepper I L. Specific detection of Salmonella spp. by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1473–1479. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1473-1479.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Widenhorn K A, Somers J M, Kay W M. Genetic regulation of the tricarboxylate transport operon (tctI) of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4436–4441. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.8.4436-4441.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Widenhorn K A, Somers J M, Kay W W. Expression of the divergent tricarboxylate operon (tctI) of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:3223–3227. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.7.3223-3227.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zieg J, Simon M. Analysis of the nucleotide sequences of an invertible controlling element. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:4196–4200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]