Abstract

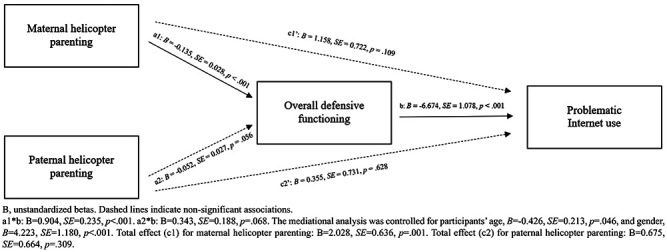

The increasing use of the Internet has raised concerns about its problematic use, particularly among emerging adults who grew up in a highly digitalized world. Helicopter parenting, characterized by excessive involvement, overcontrol, and developmentally inappropriate behavior, has been identified as a potential factor contributing to problematic Internet use (PIU). Under these circumstances, considering that emerging adults navigate their adult lives and strive to reduce their sense of being in-between, implicit emotion regulation strategies, such as defense mechanisms, may help comprehend PIU. The present questionnaire-based study investigated the associations between maternal and paternal helicopter parenting and PIU through defensive functioning among a community sample of 401 cisgender emerging adults (71.82% females; 82.04% heterosexuals; Mage=24.85, SD=2.52) living in Italy. About one-fourth (25.19%) reported PIU. Greater maternal, B=0.904, SE=0.235, p<.001, but not paternal, B=0.343, SE=0.188, p=.068, helicopter parenting was significantly associated with PIU through a less mature defensive functioning. Conversely, neither maternal, B=1.158, SE=0.722, p=.109, nor paternal, B=0.355, SE=0.731, p=.628, helicopter parenting had a direct association with PIU. The results suggest the importance for psychotherapists to incorporate individuals’ defense mechanisms and parent–child relationship history when designing tailored interventions for effective treatment of PIU. This emphasis is crucial because, in the context of a developmentally appropriate parenting style, relying on more mature defenses after psychotherapeutic intervention can lead to healthier adjustment among emerging adults.

Key words: problematic Internet use, Internet, defense mechanisms, emerging adulthood, helicopter parenting

Introduction

Globally, over five billion individuals use the Internet, comprising 63.1% of the world’s population. Out of this figure, social media users account for 4.7 billion individuals, representing 59% of the global population (Statista, 2023). As of July 2022, in Italy, where this study was conducted, 54,798,299 individuals used the Internet (90.8% penetration rate), accounting for 7.3% of European users (Internet World Stats, 2023). Alongside the rise in Internet use, there have been growing concerns regarding problematic use across various domains, such as video gaming, social media, web-streaming, pornography consumption, and online shopping. Available evidence suggests that problematic Internet use (PIU) might result in significant psychological, social, school and/or work difficulties (Beard & Wolf, 2001).

Interestingly, there is no consensus on the definition and conceptualization of PIU. A first definition identified PIU as a psychological addiction to the Internet accompanied by loss of control over online time: this perspective does not consider hypothetical correspondences with compulsive behaviors (e.g., Gámez-Guadix et al., 2013). An alternative perspective posited that the Internet medium is not inherently problematic but rather the various applications and activities it enables. In this view, PIU is characterized as a pattern of compulsive Internet use (e.g., Griffiths, 2000). In this line, Griffiths and colleagues (2016) uncovered an essential distinction between addiction to the Internet and addictions on the Internet, differentiating between generalized PIU and specific Internet use (i.e., gaming, shopping). A third perspective drew attention to the similarities between PIU and addictive behaviors regarding their effects on overall adaptation and introduced the concept of “Internet addiction” (e.g., Young, 1998). Finally, a fourth contribution conceptualized PIU primarily as a misuse of Internet applications, particularly Internet gaming (for a discussion, see Anderson et al., 2017; Spada, 2014). Further on, the last edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2022) features an Internet Gaming Disorder within the “Conditions for Further Study,” whereas the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2019) includes both a Gaming disorder, predominantly online, and a Gambling disorder, predominantly online, under the Disorders due to addictive behaviors category.

Despite differences in terminology, there seems to be a consensus that PIU is related to several negative consequences for everyday functioning, interpersonal relationships, and emotional well-being (e.g., Aboujaoude, 2010; Benzi et al., 2023; Fontana et al., 2022, 2023; Schimmenti et al., 2021; Spada, 2014). In addition, features of PIU are like symptoms shown by those suffering from substance-related addictions, including unpredictable behaviors and mood fluctuations (Ko et al., 2009; Kuss et al., 2013). Yet, the line between Internet use and misuse is noticeably being overstepped. While caution should be exercised in pathologizing Internet behaviors, widespread literature identifies Internet addiction as an independent disorder and suggests interventions to treat it (e.g., Aboujaoude, 2010; Andrade et al., 2022; Kuss & Lopez-Fernandez, 2016; Zajac et al., 2017).

A further consequence of challenges in defining PIU thresholds and assessment methodologies reflects the many discrepancies regarding its prevalence in different populations (1.0-9.0%, among adolescents; 6.0-35.0%, among college students) and geographical areas (e.g., 0.7-1.0%, in Italy, in Norway and the United States; 2.0-18.0%, in the Asian regions) (Kuss & Lopez- Fernandez, 2016; Pettorruso et al., 2020). More recently, estimates indicate that PIU is increasingly growing among emerging adults, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic (Kamolthip et al., 2022): data highlight a wide-ranging prevalence from 4% to 43.8% (Burkauskas et al., 2022).

Emerging adulthood (18-29 years) is a relevant period to be examined when studying PIU. The challenges during this phase of life, including committing to romantic relationships, starting a family, pursuing higher education, living independently, or residing with family (Arnett, 2000), may trigger PIU as a coping mechanism (Pettorruso et al., 2020). Furthermore, Internet use has become a norm among emerging adults in contemporary society. This is particularly true for those who belong to the first generation of individuals to grow up alongside adolescents in a highly digitalized world. It follows that an in-depth understanding of the underlying mechanisms of PIU might generate fruitful indications for a comprehensive approach to psychological intervention in emerging adulthood.

Helicopter parenting and problematic Internet use

The concept of helicopter parenting was initially introduced in 1990 to depict how parents figuratively hover over their children, akin to helicopters, always ready to swoop in and save them from disappointments and difficult situations (Cline & Fay, 1990). By doing this, parents convey to their children the belief that they are unable to overcome challenges on their own and constantly require protection from the dangers of the world. In this vein, despite its well-meaning intentions, helicopter parenting identifies a form of excessively involved, overly controlling, and developmentally inappropriate parenting (Nelson et al., 2020; Padilla- Walker & Nelson, 2012).

Arnett’s (2000; Arnett, 2007) contribution to the concept of emerging adulthood highlights key developmental characteristics that demonstrate why helicopter parenting may lead to psychological difficulties among emerging adults. Emerging adults require the freedom to make decisions and develop their identities, reduce their feelings of being in-between, and focus on personal growth. However, when parents engage in helicopter parenting behaviors, such as excessive control, monitoring, and decisionmaking on behalf of their children, it impedes the independence and autonomy necessary for a successful transition into adulthood (Arnett, 2007).

Earlier studies investigating the link between higher levels of helicopter parenting and adverse behavioral outcomes have indicated a greater likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors such as gambling, self-harm, illegal drug use, and cigarette smoking (Romm et al., 2020), increased use of medication for anxiety and depression (LeMoyne & Buchanan, 2011), and increased sexual risk-taking behaviors, poor dietary choices, and decreased physical activity (Macias, 2019) among emerging adults. Nevertheless, there is limited understanding of whether helicopter parenting is linked to PIU in emerging adults.

Indeed, excessive Internet use could be a coping mechanism employed to avoid family conflicts (Beard, 2005) driven by a desire to alleviate negative emotions by dissociating oneself from reality (Musetti et al., 2022; Peele, 1985); similarly, helicopter parenting behaviors are often associated with offspring’s negative emotions (e.g., Love et al., 2020; Perez et al., 2020). In addition, considering PIU, a study revealed that hostile parenting contributes to searching for ways to escape negative emotions, eventually resulting in internet gaming addiction (Kwon et al., 2011). Therefore, it is plausible that emerging adults may also use the Internet to escape their parents’ overparenting behaviors. Given the few studies specifically focused on helicopter parenting and PIU, and the negative effects highlighted by previous studies on similar parenting styles (e.g., parental involvement) (e.g., Liu et al., 2022; Tóth-Király et al., 2021), there is the need to explore this association further.

Of note, it cannot be excluded that parental gender might influence the relationship between helicopter parenting and PIU differently, as previous research shows that mothers exhibit more helicopter parenting behaviors than fathers both from a perception of parents (Rousseau & Scharf, 2015) and their children (Hong & Cui, 2020; Kömürcü-Akik & Alsancak-Akbulut, 2021; Wang et al., 2021). This pattern might result from the distinct ways mothers and fathers have been socialized as females and males concerning parenting, with mothers having higher levels of participation with their children regarding direct connection, accessibility, and responsibility than fathers (Renk et al., 2003). However, whether helicopter parenting by mothers and fathers has a different impact on PIU has not been investigated thus far.

Emerging adults’ defensive functioning as a mediating mechanism

Emotion regulation skills are vital when pursuing a more independent lifestyle and transitioning into adulthood (Vaillant, 1977). Indeed, research has revealed a positive association between helicopter parenting and emotional dysregulation in emerging adults (e.g., Cui et al., 2019a; Cui et al., 2019b). Moreover, given that helicopter parenting undermines critical self-regulatory processes such as emotion regulation, this parenting style could impact other outcomes that require appropriately developed selfregulatory skills, such as addictive or problematic Internet use.

Individuals use explicit and implicit emotion regulation strategies to manage their emotions by altering their intensity, duration, and type (Braunstein et al., 2017; Gyurak et al., 2011). While explicit emotion regulation requires conscious effort, implicit emotion regulation is an effortless, ongoing process that occurs unconsciously. Both are essential for maintaining psychological well-being, but research suggests that implicit emotion regulation may be even more critical than explicit emotion regulation (Gyurak et al., 2011). Defense mechanisms are one way to regulate emotions implicitly. They are automatic, unconscious psychological processes that help individuals cope with internal conflicts and stressful situations (Cramer, 2015; Freud, 1984). According to this perspective, defense mechanisms are cognitive tactics used to protect oneself from excessive anxiety or other negative emotions and prevent a decrease in self-esteem and self-integration (Cramer, 2008). Defense mechanisms range from maladaptive defenses (e.g., acting out or passive aggression) to highly adaptive defenses (e.g., humor and altruism; Perry, 1990; Vaillant et al., 1986) and operate along a continuum.

Given their dynamic nature (Cramer, 1987; MacGregor & Olson, 2005; Vaillant, 1971; Vaillant, 2020), people are likely to use an extensive range of defense mechanisms, though each person tends to have a repertoire of defenses, depending on their psychological development and personality traits (Cramer, 2015; Perry & Bond, 2012). Using mature defenses can reduce negative emotions and limit an individual’s awareness of stressful factors while enabling reflection and taking action to resolve conflicts. In contrast, when mature or middle-adaptive defenses prove ineffective or are unavailable, individuals may resort to less adaptive (i.e., immature) defense mechanisms (Cramer, 2015; Vaillant, 1977). In the context of helicopter parenting, it is reasonable that emerging adults who have adapted to a repeated experience where their parents took care of their every responsibility, anticipated problem solving, opposed risk-taking, were preoccupied with their success and happiness, and resisted their development of autonomy (Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012), are less likely to have developed more adaptive defenses.

However, it remains to be examined whether emerging adults are more likely to develop and use immature defense because of helicopter parenting and whether this is associated with more PIU. Previous research has mostly focused on explicit regulation strategies, indicating that a parenting style that is over-controlling and autonomy-discouraging (i.e., higher helicopter parenting behaviors) might prevent offspring from encountering and successfully coping with adversity, thereby depriving them of experiences that foster healthy emotion processing (e.g., Love et al., 2022; Şimşir Gökalp, 2022; Süsen et al., 2022). Similarly, the few research that has examined the association of addictive behaviors with the use of defense mechanisms pointed to a positive association with immature defensive strategies.

For instance, research has shown that gambling is associated with a significant decrease in mature defenses and an increase in immature defense mechanisms (Ciobotaru & Clinciu, 2022; Comings et al., 1995). Similarly, recent findings suggest that immature and autistic defense mechanisms may contribute to problematic mobile phone use (PMPU) in adults, as they may serve as a means of escaping anxiety and stress (Kalaitzaki et al., 2022). Some studies have suggested an association between immature defenses and PIU, such as projection, denial, autistic fantasy, passive aggression, and displacement (Waqas et al., 2016; Laconi et al., 2017; Vally et al., 2020). These findings emphasize that individuals who exhibit PIU may have limited psychological and intrapsychic resources to cope with life difficulties. However, little is still known about the impact of parenting behaviors on immature defense mechanisms and PIU.

Present study

Based on the literature discussed above, the present study aimed at investigating the link between helicopter parenting and PIU by considering the role of defensive functioning in emerging adults. Also, taking into account previous evidence that mothers tend to exhibit more helicopter parenting than fathers (Hong & Cui, 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Kömürcü-Akik & Alsancak- Akbulut, 2021; Rousseau & Scharf, 2015), the study examined whether both mothers’ and fathers’ helicopter parenting were associated with PIU. Specifically, it was hypothesized that defensive functioning would serve as a mediating mechanism, wherein emerging adults who reported higher levels of helicopter parenting would show less mature defensive functioning, which, in turn, would be associated with increased levels of PIU. As no previous research has investigated the distinct associations between maternal and paternal helicopter parenting and PIU through defensive functioning, no gender differences hypotheses were formulated beforehand.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A non-probability community sample of 401 cisgender emerging adult Internet users (M=24.85, SD=2.52; age range: 18-29 years) participated, of whom 288 (71.82%) identified as females. More than one-fifth (n=329, 82.04%) reported a heterosexual orientation, with the remaining identifying as gay/lesbian (n=38, 9.48%) or bisexual (n=34, 8.48%). All resided in Italy and spoke Italian fluently; almost all (n=392, 97.76%) were Italian citizens. The large majority (n=313, 78.06%) were students, with the remaining 75 (18.70%) being employed and 13 (3.24%) being unemployed. In terms of educational level, 5.49% (n=22) had a PhD or post-hoc specialization, 43.64% (n=175) had a master’s degree, 36.16% (n=145) had a bachelor’s degree, and 14.71% (n=59) had a high school diploma. Regarding their socioeconomic status, the minority reported a low income (n=36, 8.98%), about one-fourth (n=97, 24.19%) reported a lower-middle income, almost half (n=187, 46.63%) reported an upper-middle income, and the remaining 20.20% (n=81) reported a high income. Finally, more than half of the sample (n=219, 54.61%) lived with their parent(s), 83 (20.70%) lived alone, 56 (13.97%) lived with their friends, 38 (9.48%) cohabited, and 5 (1.25%) lived with their relatives.

Voluntary participation was emphasized among all study participants, and measures were taken to ensure privacy and anonymity through the survey design. Participants were recruited using snowballing techniques (i.e., word-of-mouth and sharing the research link on social networks). They were asked to complete the questionnaires through access to Qualtrics platform after reading and accepting the informed consent online.

Measures

Problematic Internet use

The Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 1998; Italian version, Ferraro et al., 2006) was administered to assess PIU. The IAT is a self-report questionnaire that includes 20 items (e.g., “How often do you try to hide how long you’ve been online?”) rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). IAT total scores range from 20 to 100, with a total score ≥50 indicating a problematic use. In the present study, the Cronbach’s α was .89.

Helicopter parenting

The Helicopter Parenting Instrument (HPI; Odenweller et al., 2014; Italian validation by Pistella et al., 2020) is a 15-item scale used to measure subjects’ perception of helicopter parenting (e.g., “My parent supervised my every move growing up” and “My parent often stepped in to solve life problems for me”). Responses are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of helicopter parenting. In the current study, each participant completed this scale twice – once per their mother and once for their father. Cronbach’s alpha was .80 for maternal helicopter parenting and .77 for paternal helicopter parenting.

Defensive functioning

Defensive functioning was examined through the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales-Self-Report-30 (DMRS-SR-30; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020a; Prout et al., 2022), a 30-item self-report which assesses the hierarchy of defense mechanisms as described in the DSM-IV and developed in the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scale model (DMRS; Perry, 1990; Perry & Henry, 2004). DMRSSR- 30 items were created from the original DMRS (Perry, 1990), adapted for self-report, and rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very often/much). The DMRS-SR-30 yields multiple levels of scoring: an index of defensive maturity (Overall Defensive Functioning, ODF), a score for each of the three defense categories and two subcategories (a score for seven defensive levels, and a score for 28 defense mechanisms, all in hierarchical order). The present study used the ODF score, with higher scores indicating higher defensive functioning. Cronbach’s α was .91.

Data analyses

We conducted all analyses in R (R Core Team, 2021) and interpreted significant effects at p<.05. We used the interquartile range method to identify outliers, but no outliers were found. We checked data distribution using skewness and kurtosis values: all study variables fell within acceptable values for skewness (±2) and kurtosis (±7) (West et al., 1995), indicating that the data were normally distributed. Using descriptive statistics, we presented percentages, means, and standard deviations of the variables included in the mediation model (i.e., PIU, helicopter parenting by mothers, helicopter parenting by fathers, and defensive functioning).

To assess potential gender differences in PIU and defensive functioning, we performed two analyses of variance (ANOVAs). Also, given the nested data structure regarding helicopter parenting (i.e., the same participant reporting both maternal and paternal helicopter parenting) we ran one mixed model. In addition, we conducted Pearson’s correlations between participants’ age and study variables. We included them as covariates in the following analysis if they were significantly associated with one or more study variables. To test the mediational hypothesis, we ran one mediation model with ordinary least square (OLS) regression (using R mediation package) and computed 95% confidence intervals with bootstrap percentiles and 5,000 resamples, following Hayes’s (2017) recommendations.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Out of the 401 participants, 101 (25.19%) emerging adults fell in the range for a moderate to severe level of PIU (score ≥50). A preliminary mixed model indicated, on average, higher scores of helicopter parenting by mothers than by fathers, estimate = -0.435, SE=.051, p<.001. Regarding gender differences, male participants reported higher mean scores of PIU, F(1,399)=10.529, p=.001, η²p=0.026, relative to female participants (M=44.982, SD=12.734; M=40.969, SD=10.456, respectively). Conversely, male and female participants showed similar mean scores of overall defensive functioning, F(1,399)=0.079, p=.778, η²p<0.001 (M=5.077, SD=.479; M=5.092, SD=0.451, respectively). Likewise, there were no significant gender differences either in helicopter parenting by mothers (males: M=3.527, SD=0.967; females: M=3.536, SD=0.889) or in helicopter parenting by fathers (males: M=3.192, SD=0.818; females: M=3.061, SD=0.889), Wilks’λ(2, 250)=0.995, p=.336, η²p=0.005.

Pearson’s r correlations highlighted a significant, albeit small, positive associations between PIU and helicopter parenting by mothers, r(399)=.198, p<.001, and fathers, r(399)=.132, p=.008. Moreover, higher PIU was associated with less mature overall defensive functioning, r(399)=-.319, p<.001, while more mature overall defensive functioning was associated with lower levels of helicopter parenting by mothers, r(399)=-.302, p<.001. A significant, small, negative association was found between mature overall defensive functioning and helicopter parenting by fathers, r(399)=-.190, p<.001. Also, helicopter parenting by mothers and fathers were positively associated, r(399)=.344, p<.001. Finally, younger participants reported lower PIU, r(399)=-.122, p=.015, lower helicopter parenting by mothers, r(399)=-.141, p=.005, and more mature overall defensive functioning, r(399)=.129, p=.010. Participants’ age was not significantly associated with helicopter parenting by fathers, r(399)=-.097, p=.051. Table 1 displays significant and nonsignificant associations.

Problematic Internet use and helicopter parenting: defensive functioning as a mediating mechanism

One mediation model was run with helicopter parenting by mothers and helicopter parenting by fathers as predictors, overall defensive functioning as a mediator, and PIU as an outcome. Given the significant association between participants’ age and PIU, and gender differences in PIU, age and gender were entered as covariates. The results indicated that the indirect association between mothers’ helicopter parenting and PIU through overall defensive functioning was significant, while for fathers’ helicopter parenting such indirect association was not significant. Specifically, emerging adults reporting higher levels of helicopter parenting by mothers also showed a less mature overall defensive functioning, which, in turn, was associated with greater PIU. Neither maternal helicopter parenting nor paternal helicopter parenting were directly associated with emerging adults’ PIU. Overall, the full model explained 15% of the variance (p<.001). Figure 1 displays a graphical representation of the model, with estimates of each path.

Discussion

The present study identified helicopter parenting and defensive functioning as factors involved in PIU among emerging adults. Although neither maternal nor paternal helicopter parenting were directly linked to PIU, higher levels of helicopter parenting by mothers, but not by fathers, were significantly associated with Internet use through a less mature overall defensive functioning. This result aligns with the sex-role theory, according to which mothers and fathers play distinct roles in the lives of their offspring resulting in certain disparities in developmental outcomes, with mothers being more likely to be overinvolved in their offspring’s everyday life than fathers (Renk et al., 2003). In this vein, the present study suggests that such maternal overinvolvement may also be related to PIU in emerging adults through their reliance on less mature defensive functioning.

Regarding the significant mediated relation found, very little is known about the link between defenses development and specific parenting styles (e.g., Cramer, 1991; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020b; Malberg et al., 2017). That premised, a psychodynamic perspective on the consequences of helicopter parenting by mothers for emerging adults’ defensive development may help interpret the results. It is reasonable that in a relationship with a helicopter mother, the emerging adult has internalized the idea that the only way to preserve the bond with their mother is to leave room for her. While such a “pathological accommodation” (Brandchaft, 1993) operates on an unconscious level to preserve a necessary connection, especially when it has been perceived as fragile and inconsistent and can provide a sense of comfort to a growing child, the developmental demands arising during emerging adulthood can challenge this pattern. In fact, should the emerging adult feel tight in the relationship with their helicopter mother and express the wish to cope alone with their own experience, they may find themselves ill-equipped for mature defenses to alleviate potential distress and conflicts encountered in their daily life or even caused by the mother-emerging adult relationship.

Table 1.

Mean scores, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations among emerging adults’ problematic internet use, maternal and paternal helicopter parenting, overall defensive functioning, and age (N=401).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Problematic Internet use | 1.00 | 42.100 | 11.275 | ||||

| 2. Maternal helicopter parenting | .198*** | 1.00 | 3.533 | 0.910 | |||

| 3. Paternal helicopter parenting | .132** | .344*** | 1.00 | 3.098 | 0.871 | ||

| 4. Overall defensive functioning | -.319*** | -.302*** | -.190*** | 1.00 | 5.088 | 0.458 | |

| 5. Age | -.122* | -.141** | -.097 | .129* | 1.00 | 24.848 | 2.520 |

SD, standard deviation. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Figure 1.

Mediation of overall defensive functioning in the association between maternal and paternal helicopter parenting, and problematic Internet use in emerging adulthood (N=401).

A complementary interpretation is that emerging adults with a history of helicopter parenting have unconsciously adopted their mothers’ views and feelings at their own expense. As a result, helicopter parenting may implicitly make them feel like their mother believes them incapable of dealing with stressors autonomously. Over time, an offspring who has been protected from threat to an unnecessary or excessive degree likely have developed a representation of self as someone unable to overcome threats without maternal assistance and a representation of the other (i.e., the mother) as someone who is solicited to step in on their behalf to manage stress and conflict. These representations may parallel the development of a less mature defensive functioning, which originates in adaptation and is shaped by experience, particularly by early relationships with the primary caregiver (typically the mother in heterosexual two-parent families). Under these circumstances, although potentially problematic, the Internet promises an alternative place to the mother-emerging adult relationship where emerging adults can master the (virtual) reality and regulate negative feelings, although maladaptively.

Of relevance, this was the first investigation of defensive functioning (i.e., the implicit side of emotion regulation) as a mediating mechanism of the relation between helicopter parenting and PIU, whereas previous studies considered explicit emotion regulation strategies (i.e., coping) (Love et al., 2022; Şimşir Gökalp, 2022; Süsen et al., 2022). Indeed, as social media and other digital devices may initially be used as a way to alleviate negative emotions (Pettorruso et al., 2020), a lack of appropriate emotional regulation skills (developed as a result of overprotective parenting), might foster emerging adults’ using media as a means of coping with negative emotions. Over time, this behavior can become habitual and lead to addiction as they increasingly rely on this escape mechanism. In this study, we highlight that employing emotional regulation strategies may not be a conscious choice but rather stem from implicit mechanisms, such as defense mechanisms. What is problematic is not the escape behavior from the helicopter parents per se (Pettorruso et al., 2020) as the psychic configuration underlying such behavior. Thus, defensive functioning as a significant mediating mechanism should be situated within the interpretation of the Internet as a psychic retreat (Schimmenti & Caretti, 2010; Steiner, 1993).

During emerging adulthood, autonomy and independence are crucial for healthy development and behavior. This study proposes that Internet use may fulfill several functions that aid in escaping from maternal parenting that is excessively involved, overly controlling, and developmentally inappropriate (Amichai-Hamburger, 2002; Nelson et al., 2020; Padilla-Walker & Nelson, 2012). In addition, the characteristics of the Internet, such as anonymity, complete control over the technological tool facilitating interaction, and physical distance between communicating individuals, may enable the counteraction of strong emotional stress and promote withdrawal into specific areas of the mind that foster feelings of omnipotence and the emergence of weakly explored self-states (Schimmenti & Caretti, 2010).

Four levels of immature defenses exist: minor image-distorting (e.g., devaluation, idealization, omnipotence), disavowal (e.g., denial, projection, rationalization, autistic fantasy), major imagedistorting (e.g., projective identification, splitting of self-image, splitting of other’s image), and action (e.g., acting out, help-rejecting complaining, passive aggression) (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020b; Perry, 1990; Prout et al., 2022). Therefore, in this study context, it is reasonable that less mature defensive functioning can manifest in various forms, including a withdrawal from reality through online activities (autistic fantasy), a self-image construction for online social networking platforms (idealization, splitting of self-image), a displacement of rigidity experienced in the relation with their helicopter mother into the online setting expressed right through a certain rigidity in online activities (projective identification, acting out), the connection with a communicative partner that can be turned on or off based on the subject’s wish (omnipotence) conversely to what happens when the helicopter mother is physically present.

Even though the present study has generated novel insights regarding links between helicopter parenting, defensive functioning, and PIU, several limitations should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, as with many studies in the field, the use of a convenience sample comprising cisgender, mainly female, heterosexual, and student, emerging adults, coupled with the non-probability sampling method, limit the generalizability and representativity of the results. Future research should recruit a more diverse sample to increase the results generalizability to the entire population of emerging adults, who include both students and employees and may thus prioritize, and cope with, the normative challenges brought by this developmental period differently. In this vein, a future larger sample would also allow to examine in more depth whether the mediated relation we found differ across genders and the different age groups, given that both variables significantly weighted on the associations analyzed.

As a second limitation, the cross-sectional design limits the potential to establish causality and introduces the possibility of reverse causation. Although previous research pointed to a linear direction from helicopter parenting to PIU (Love et al., 2022; Şimşir Gökalp, 2022; Süsen et al., 2022) and defensive functioning is reasonably shaped also by parenting (Cramer, 1991; Malberg et al., 2017), future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the temporal order of the processes. In addition, this study used self-report questionnaires exclusively, known to have potential biases (such as social desirability and difficulty with memory recall). While the measures used are widely employed in research and have demonstrated good psychometric properties, it is possible that a multimethod assessment of the study variables would have yielded more valid and reliable findings. Additionally, the DMRS-SR-30 only assessed the conscious aspect of defenses that individuals could report about themselves. However, the ODF score employed in this study showed excellent reliability consistent with previous validation studies (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020a; Prout et al., 2022). Finally, given that about one-fourth of participants reported moderate to severe levels of PIU, future research should include a larger clinical group of emerging adults with PIU to compare and expand upon our findings and provide further insights across different levels of Internet use severity.

Examining defensive functioning as a mediating mechanism of the relation between helicopter parenting and PIU has essential treatment implications as it helps explain the inner motives underlying Internet use. In this vein, the results suggest the importance for psychotherapists to incorporate individuals’ defense mechanisms and parent–child relationship history when designing tailored interventions for effective treatment of PIU (Carone et al., 2023). This focus is crucial because, in the context of a developmentally appropriate parenting style, the reliance on more mature defenses after psychotherapeutic intervention can lead to healthier adjustment among emerging adults (Di Riso et al., 2011; 2015; Perry & Bond, 2012; Prout et al., 2019).

Similarly, a refuge on the Internet has been interpreted so far mainly as a defense from non-responsive or neglecting parents who do not facilitate their offspring in mentalizing their intolerable affects (Lingiardi, 2008; Musetti et al., 2020; Schimmenti & Caretti, 2010). The present study emphasizes that Internet may configure a psychic retreat (Steiner, 1993) also for individuals with helicopter parents, especially mothers, who push the boundaries of the relationship stepping into their offspring’s lives to manage their problems. Under these circumstances, treating PIU in emerging adults who are transitioning into adulthood and must deal with new developmental tasks, including eventually forming their own family and having children, may prevent the intergenerational transmission of helicopter parenting through maladaptive defense mechanisms.

Further preventive treatment may consider the developmental roots of helicopter parenting and PIU, which likely originate before emerging adulthood (e.g., in adolescence; Anderson et al., 2017). In this vein, psychotherapists working with Internet addicted- adolescents and their helicopter mothers can explore the intergenerational history of these parents. For example, it can be hypothesized that if parents have not achieved autonomy in their family of origin, they may feel intensely and disproportionately responsible for their offspring, regardless of their developmental stage, and project anxiety onto their offspring through controlling- and autonomy-limiting parenting behavior. In parallel, psychotherapists might help these offspring understand that their behaviors, including seeking refuge in the digital world, might trigger their parents’ behaviors in a vicious cycle.

Conclusions

In conclusion, more in-depth future studies examining both further family-related variables (e.g., attachment; Cacioppo et al., 2019; Musetti et al., 2022) and individual variables (e.g., psychopathology, personality; Laconi et al., 2017; Vally et al., 2020), as well as defensive profiles, in problematic Internet users will provide psychotherapists with fine-grained tools for distinguishing dissimilar expressions of psychic retreats, accurately assessing, and eventually treating Internet addictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all individuals who participated in the project.

Funding Statement

Funding: no funding was received for this project.

References

- Aboujaoude E. (2010). Problematic Internet use: an overview. World Psychiatry, 9(2), 85-90. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00278.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Amichai-Hambuger Y. (2002). Internet and personality. Computers in Human Behavior, 18(1), 1-10. doi: 10.1016/S0747-5632 (01)00034-6 [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. L., Steen E., Stavropoulos V. (2017). Internet use and problematic Internet use: a systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(4), 430-454. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716 [Google Scholar]

- Andrade A. L. M., Di Girolamo MartinsG., Scatena A., Lopes F. M., de Oliveira W. A., Kim H. S., De Micheli D. (2022). The effect of psychosocial interventions for reducing co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety in individuals with problematic internet use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00846-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A development theory from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469-480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: what is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 68-73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. W. (2005). Internet addiction: a review of current assessment techniques and potential assessment questions. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 8, 7-14. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. W., Wolf E. M. (2001). Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4(3), 377-383. doi: 10.1089/109493101300210286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzi I. M. A., Carone N., Fontana A., Barone L. (2023). Problematic Internet use in emerging adulthood: the interplay between narcissistic vulnerability and environmental sensitivity. Journal of Media Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1027/1864-1105/a000386 [Google Scholar]

- Brandchaft B. (1993). To free the spirit from its cell. In: Progress in Self Psychology, vol. 10 (pp. 209-230). Analytic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein L. M., Gross J. J., Ochsner K. N. (2017). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a multi-level framework. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(10), 1545-1557. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkauskas J., Gecaite-Stonciene J., Demetrovics Z., Griffiths M. D., Király O. (2022). Prevalence of problematic Internet use during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 46, 101179. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo M., Barni D., Correale C., Mangialavori S., Danioni F., Gori A. (2019). Do attachment styles and family functioning predict adolescents’ problematic Internet use? A relative weight analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1263-1271. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01357-0 [Google Scholar]

- Carone N., Benzi I. M. A., Parolin L. A. L., Fontana A. (2023). “I can’t miss a thing” – The contribution of defense mechanisms, grandiose narcissism, and vulnerable narcissism to fear of missing out in emerging adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 214, 112333. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2023. 112333 [Google Scholar]

- Ciobotaru C. M., Clinciu A. I. (2022). Impulsivity, consciousness and defense mechanisms of the ego among pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling studies, 38(1), 225-234. doi: 10.1007/s10899-021-10035-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster C., Fay J. (1990). Parenting with love and logic: teaching children responsibility. Pinion. [Google Scholar]

- Comings D. E., MacMurray J., Johnson P., Dietz G., Muhleman D. (1995). Dopamine D2 receptor gene (DRD2) haplotypes and the defense style questionnaire in substance abuse, Tourette syndrome, and controls. Biological Psychiatry, 37(11), 798-805. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94) 00222-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (1987). The development of defense mechanisms. Journal of Personality, 55(4), 597-614. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00454.x [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (1991). The development of defense mechanisms: Theory, research, and assessment. Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2008). Seven pillars of defense mechanism theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2, 1963-1981. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00135.x [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2015). Defense mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(2), 114-122. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2014.947997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Allen J., Fincham F. D., May R. W., Love H. (2019a). Helicopter parenting, self-regulatory processes, and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Adult Development, 26, 97-104. doi: 10.1007/s10804-018-9301-5 [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Darling C. A., Coccia C., Fincham F. D., May R. W. (2019b). Indulgent parenting, helicopter parenting, and well-being of parents and emerging adults. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 860-871. doi: 10.1007/ s10826-018-01314-3 [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C. (2021). The hierarchy of defense mechanisms: assessing defensive functioning with the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort (DMRS-Q). Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 718440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.718440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Lucchesi M., Michelini M., Vitiello S., Piantanida A., Conversano C. (2020a). Preliminary validity and reliability of the novel self-report based on the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales (DMRS-SR-30). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 870. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Prout T. A., Fabiani M., Kui T. (2020b). Defensive profile of parents of children with externalizing problems receiving Regulation-Focused Psychotherapy for Children (RFP-C): A pilot study. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8(2). doi: 10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp- 2515 [Google Scholar]

- Di Riso D., Colli A., Chessa D., Marogna C., Condino V., Lis A., Lingiardi V., Mannarini S. (2011). A supportive approach in psychodynamic-oriented psychotherapy. An empirically supported single case study. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 14(1), 49-89. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2011.43 [Google Scholar]

- Di Riso D., Gennaro A., Salcuni S. (2015). Defensive mechanisms and personality structure in an early adolescent boy: Process and outcome issues in a non-intensive psychoanalytically oriented psychotherapy. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 18(2), 114-128. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2015.176 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro G., Caci B., D’amico A., Blasi M. D. (2006). Internet addiction disorder: an Italian study. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 170-175. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2006.9972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A., Benzi I. M. A., Cipresso P. (2022). Problematic Internet use as a moderator between personality dimensions and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescence. Current Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-02409-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A., Benzi I. M. A., Ghezzi V., Cianfanelli B., Sideli L. (2023). Narcissistic traits and problematic internet use among youths: a latent change score model approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 212, 112265. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2023.112265 [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1984). The neuropsychosis of defense. Standard Edition Vol. 3, pp. 41-61. The Hogart Press and the Institute of Psycho- Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Guadix M., Orue I., Smith P. K., Calvete E. (2013). Longitudinal and reciprocal relations of cyberbullying with depression, substance use, and problematic internet use among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53, 446-452. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D. (2000). Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 3(2), 211-218. doi: 10.1089/109493100316067 [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. D., Kuss D. J., Billieux J., Pontes H. M. (2016). The evolution of Internet addiction: A global perspective. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 193-195. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015. 11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyurak A., Gross J. J., Etkin A. (2011). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a dual-process framework. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 400-412. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.544160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hong P., Cui M. (2020). Helicopter parenting and college students’ psychological maladjustment: the role of self-control and living arrangement. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 338-347. doi: 10.1007/ s10826-019-01541-2 [Google Scholar]

- Internet World Stats (2023). Retrieved from: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats4.htm#europe [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki A., Laconi S., Spritzer D. T., Hauck S., Gnisci A., Sergi I., Sahlan R. N. (2022). The prevalence and predictors of problematic mobile phone use: A 14-country empirical survey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-20. doi: 10.1007/s11469-022-00901-2 [Google Scholar]

- Ko C. H., Yen J. Y., Chen C. S., Yeh Y. C., Yen C. F. (2009). Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for Internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medical, 163, 937-943. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kömürcü-Akik B., Alsancak-Akbulut C. (2021). Assessing the psychometric properties of mother and father forms of the helicopter parenting behaviors questionnaire in a Turkish sample. Current Psychology. Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01652-4 [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D. J., Lopez-Fernandez O. (2016). Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: a systematic review of clinical research. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 143-176. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss D. J., Griffiths M. D., Binder J. F. (2013). Internet addiction in students: prevalence and risk factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 959-966. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon J. H., Chung C. S., Lee J. (2011). The effects of escape from self and interpersonal relationship on the pathological use of internet games. Community Mental Health Journal, 47, 113-121. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9236-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laconi S., Vigouroux M., Lafuente C., Chabrol H. (2017). Problematic internet use, psychopathology, personality, defense and coping. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 47-54. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.025 [Google Scholar]

- LeMoyne T., Buchanan T. (2011). Does “hovering” matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 31(4), 399-418. doi: 10.1080/02732173.2011. 574038 [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V. (2008). Playing with unreality: transference and computer. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 89, 1, 111-126. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-8315.2007.00014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Wang X., Zou S., Wu X. (2022). Adolescent problematic Internet use and parental involvement: The chain mediating effects of parenting stress and parental expectations across early, middle, and late adolescence. Family Process, 61(4), 1696-1714. doi: 10.1111/famp.12757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love H., Cui M., Allen J., Fincham F. D., May R. W. (2020). Helicopter parenting and female university students’ anxiety: does parents’ gender matter? Families, Relationships and Societies, 9, 417-430. doi: 10.1332/ 204674319X15653625640669 [Google Scholar]

- Love H., May R. W., Shafer J., Fincham F. D., Cui M. (2022). Overparenting, emotion dysregulation, and problematic internet use among female emerging adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 79, 101376. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101376 [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor M. W., Olson T. R. (2005). Defense mechanisms: their relation to personality and health. An exploration of defense mechanisms assessed by the Defense-Q. In Columbus A. (Ed.), Advances in psychology research, Vol. 36 (p. 95-141). Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Macias L. (2019). Helicopter parenting and the relationship to health behaviors during emerging adulthood. PhD Dissertation. Palo Alto University. [Google Scholar]

- Malberg N., Rosenberg L., Malone J. C. (2017). Emerging personality patterns and difficulties in childhood. In Lingiardi V., McWilliams N. (Eds.), Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual, second edition: PDM-2 (pp. 501-539). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Musetti A., Corsano P., Boursier V., Schimmenti A. (2020). Problematic Internet use in lonely adolescents: The mediating role of detachment from parents. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(1), 3-10. doi: 10.36131/clinicalnpsych20200101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musetti A., Grazia V., Alessandra A., Franceschini C., Corsano P., Marino C. (2022). Vulnerable narcissism and problematic social networking sites use: focusing the lens on specific motivations for social networking sites use. Healthcare, 10(9), 1719. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musetti A., Manari T., Billieux J., Starcevic V., Schimmenti A. (2022). Problematic social networking sites use and attachment: a systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 107199. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107199 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson L. J., Padilla-Walker L. M., Christensen K. J., Evans C. A., Carroll J. S. (2011). Parenting in emerging adulthood: an examination of parenting clusters and correlates. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 730-743. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9584-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenweller K. G., Booth-Butterfield M., Weber K. (2014). Investigating helicopter parenting, family environments, and relational outcomes for millennials. Communication Studies, 65(4), 407-425. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2013.811434 [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker L. M., Nelson L. J. (2012). Black hawk down? Establishing helicopter parenting as a distinct construct from other forms of parental control during emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1177-1190. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence. 2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peele S. (1985). The meaning of addiction: Compulsive experience and its interpretation. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Perez C. M., Nicholson B. C., Dahlen E. R., Leuty M. E. (2020). Overparenting and emerging adults’ mental health: the mediating role of emotional distress tolerance. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 374-381. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01603-5 [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (1990). Defense Mechanism Rating Scales (DMRS) (5th ed.). Author. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Bond M. (2012). Change in defense mechanisms during long-term dynamic psychotherapy and five-years outcome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 69, 916-925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Henry M. (2004). Studying defense mechanisms in psychotherapy using the Defense Mechanism Rating Scales. In Hentschel U., Smith G., Draguns J. G., Ehlers W. (Eds.), Defense mechanisms: Theoretical, research and clinical perspectives (pp. 165-192). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Pettorruso M., Valle S., Cavic E., Martinotti G., di Giannantonio M., Grant J. E. (2020). Problematic Internet use (PIU), personality profiles and emotion dysregulation in a cohort of young adults: trajectories from risky behaviors to addiction. Psychiatry Research, 289, 113036. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistella J., Izzo F., Isolani S., Ioverno S., Baiocco R. (2020). Helicopter mothers and helicopter fathers: Italian adaptation and validation of the Helicopter Parenting Instrument. Psychology Hub, 37(1), 37-46. doi: 10.13133/2724-2943/16900 [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Di Giuseppe M., Zilcha-Mano S., Perry J. C., Conversano C. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales-Self-Report-30 (DMRS-SR- 30): internal consistency, validity and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 104(6), 833-843. doi: 10.1080/ 00223891.2021.2019053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Malone A., Rice T., Hoffman L. (2019). Resilience, defense mechanisms, and implicit emotion regulation in psychodynamic child psychotherapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 49, 235-244. doi: 10.1007/s10879-019-09423-w [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2021). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Renk K., Roberts R., Roddenberry A., Luick M., Hillhouse S., Meehan C., Oliveros A., Phares V. (2003). Mothers, fathers, gender role, and parents’ time with their children. Sex Roles, 48(7/8), 305-315. doi: 10.1023/A:1022934412910 [Google Scholar]

- Romm K. F., Barry C. M., Alvis L. M. (2020). How the rich get riskier: parenting and higher-SES emerging adults’ risk behaviors. Journal of Adult Development, 27, 281-293. doi: 10.1007/s10804-020-09345-1 [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau S., Scharf M. (2015). “I will guide you”: the indirect link between overparenting and young adults’ adjustment. Psychiatry Research, 228(3), 826-834. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Caretti V. (2010). Psychic retreats or psychic pits? Unbearable states of mind and technological addiction. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 27(2), 115-132. doi: 10.1037/ a0019414 [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Musetti A., Costanzo A., Terrone G., Maganuco N. R., Aglieri RinellaC., Gervasi A. M. (2021). The unfabulous four: maladaptive personality functioning, insecure attachment, dissociative experiences, and problematic Internet use among young adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 447-461. doi: 10.1007/ s11469-019-00079-0 [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti A., Passanisi A., Gervasi A. M., Manzella S., Famà F. I. (2014). Insecure attachment attitudes in the onset of problematic Internet use among late adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45(5), 588-595. doi: 10.1007/ s10578-013-0428-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segrin C., Woszidlo A., Givertz M., Montgomery N. (2013). Parent and child traits associated with overparenting. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 32, 569-595. doi: 10.1521/ jscp.2013.32.6.569 [Google Scholar]

- Şimşir GökalpZ. (2022). Examining the relationships between helicopter parenting, self-control, self-efficacy, and multiscreen addiction among Turkish emerging adults. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2022.2151336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spada M. M. (2014). An overview of problematic Internet use. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013. 09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statista (2023). Retrieved from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide/ [Google Scholar]

- Steiner J. (1993). Psychic retreats. Pathological organizations of the personality in psychotic, neurotic and borderline patients. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Süsen Y., Halil P. A. K., Çevik E. (2022). Helicopter parenting, self-control, and problematic online gaming in emerging adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology Research, 6(3), 331-341. doi: 10.5455/kpd.26024438m000070 [Google Scholar]

- Tóth-Király I., Morin A. J., Hietajärvi L., Salmela-Aro K. (2021). Longitudinal trajectories, social and individual antecedents, and outcomes of problematic Internet use among late adolescents. Child Development, 92(4), e653-e673. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G.E. (2020) Defense mechanisms. In Zeigler-Hill V., Shackelford T.K. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1372 [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1971). Theoretical hierarchy of adaptive ego mechanisms: A 30-year follow-up of 30 men selected for psychological health. Archives of General Psychiatry, 24(2), 107-118. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1971.017500800 11003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1977). Adaptation to life. Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E., Bond M., Vaillant C. O. (1986). An empirically validated hierarchy of defense mechanisms. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43(8), 786-794. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080072010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vally Z., Laconi S., Kaliszewska-Czeremska K. (2020). Problematic Internet use, psychopathology, defense mechanisms, and coping strategies: A cross-sectional study from the United Arab Emirates. Psychiatric Quarterly, 91, 587-602. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09719-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lai R., Yang A., Yang M., Guo Y. (2021). Helicopter parenting and depressive level among non-clinical Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 522-529. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas A., Rehman A., Malik A., Aftab R., Allah Yar A., Allah Yar A., Rai A. B. (2016). Exploring the association of ego defense mechanisms with problematic Internet use in a Pakistani medical school. Psychiatry Research, 243, 463-468. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West S. G., Finch J. F., Curran P. J. (1995). Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Hoyle R. H. (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications (pp. 56-75). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). Author. [Google Scholar]

- Young K. S. (1998). Caught in the net. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Zajac K., Ginley M. K., Chang R., Petry N. M. (2017). Treatments for Internet gaming disorder and Internet addiction: A systematic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 979-994. doi: 10.1037/adb0000315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]