Abstract

Few studies examine outcomes by surgical approach in non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with N2 disease. We examined time trends in surgical approach and outcomes among patients undergoing minimally invasive (MIS, robotic and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery [VATS]) vs open lobectomy in this patient population. We performed a retrospective analysis of patients from the National Cancer Database diagnosed with clinical Stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC from 2010 to 2016. We examined the yearly proportion of MIS vs open resections. Multivariable regression was used to assess the association of surgical approach with length of stay, unplanned readmissions, 30-day and 90-day mortality. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to assess the association of surgical approach with 5-year overall mortality. We identified 5741 patients who underwent lobectomy for Stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC (459 robotic, 1403 VATS, 3879 open). From 2010 to 2016, the proportion of minimally invasive procedures increased from 20% to 45%. MIS patients, on average, stayed 1 day less in the hospital (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.7, 1.5) and had lower odds of 90-day (odds ratio [OR] 0.74; 95% CI 0.54, 0.99) and 5-year mortality (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75, 0.91), compared to open resections. There was no difference in odds of readmission by surgical approach (OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.71, 1.33). Among MIS procedures, robotic resections had lower odds of 90-day mortality (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.18, 0.97) than VATS. Among patients undergoing lobectomy for locally advanced N2 NSCLC robotic and VATS techniques appear safe and effective compared to open surgery and may offer short- and long-term advantages.

Keywords: Locally advanced non–small-cell lung cancer, Minimally invasive surgery

Graphical Abstract:

MIS lobectomy in Stage IIIA N2 NSCLC has improved outcomes compared to open lobectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Based on the seventh edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system, lung cancers staged as Stage IIIA non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) represent a heterogeneous group that includes subsets of patients with mediastinal lymph node involvement (ie, T1–3 N2) or patients with locally advanced disease (T4 N0–1).1 While the treatment paradigm for N2 disease continues to evolve, current consensus guidelines recommend a multidisciplinary approach that includes induction chemotherapy with or without radiation and surgical resection in select patients without bulky, multistation N2 disease.2–4

Surgical resection for N2 disease has been largely performed via thoracotomy in clinical trials.5 Yet, minimally invasive (MIS) approaches inclusive of both video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and robotic-assisted procedures are generally preferred over thoracotomy for early stage NSCLC due to improved short-term outcomes including decreased length of stay (LOS), fewer postoperative complications, shorter interval between surgery and initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy, and improved survival.6–12 Robotic-assisted pulmonary resection may provide added advantages over a VATS approach, including reduced blood loss, less postoperative pain, shorter LOS, and lower conversion to open rates particularly among high volume surgeons (>20 cases per year).13–15

Prior studies comparing MIS and open lobectomy outcomes in locally advanced lung cancer are limited to smaller single institution samples, do not include robotic resections, and/or include a heterogeneous locally advanced NSCLC population.16–20 Given the relative paucity of data regarding MIS resections in Stage IIIA, we queried the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to examine a large cohort of patients with surgically resected Stage IIIA-N2 disease. Our objective was to describe trends in surgical approach over time, short-term outcomes and 5-year overall survival in patients undergoing MIS vs open lobectomy in this population. We hypothesized that outcomes would be no different in patients undergoing the MIS approach as opposed to the open approach.

METHODS

Study Design, Data Source, and Participants

This was a retrospective cohort analysis using the NCDB, a nationwide hospital-based cancer registry of more than 1500 Commission on Cancer-certified facilities in the United States and jointly sponsored by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society.21 The database covers approximately 70% of all newly diagnosed cancers and provides clinical, diagnostic, staging, treatment, and outcomes information.

We used the 2016 NSCLC Participant User File to identify adults with clinical Stage IIIA-N2 (T1N2M0, T2N2M0, T3N2M0) NSCLC who underwent lobectomy or bi-lobectomy (NCDB primary surgery codes 30, 33, 45, 46, 47, 48) from 2010 to 2016. This time frame was used because the surgical approach was not available prior to 2010 and because it was a period of uniform staging based on the seventh edition of the AJCC standards. Patients were excluded if they had a history of previous cancer. A CONSORT diagram showing inclusion/exclusion criteria and final sample derivation is shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

The primary study exposure of interest was surgical approach, defined as MIS (robotic- or VATS) and open (all other). We also performed subgroup analysis comparing robotic-assisted to VATS procedures. Minimally invasive cases converted to open were considered minimally invasive (intent-to-treat approach) to avoid biasing the open approach group toward worse outcomes, since factors leading to conversion may also predispose to worse outcomes. Sensitivity analysis using an as treated approach did not change our findings.

We examined both short- and long-term outcomes after surgery. The short-term outcomes assessed were LOS, 30-day unplanned readmission, 30-day mortality, and 90-day mortality. Additional secondary outcomes assessed were lymph nodes examined, margin positivity, and conversion rates (comparing robotic vs VATS approaches). The long-term outcome assessed was 5-year overall mortality.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics among robotic, VATS, and open approaches were compared with chi-squared analysis for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables (age). Trends in the yearly percentage of MIS and open lobectomies were evaluated with a Spearman’s rank correlation test. Student’s t test and chi-squared analyses were used to compare the number of lymph nodes and margin positivity rates, respectively, between MIS and open approaches as well as robotic and VATS approaches overall and in high-volume centers (defined as >20 surgical cases per facility per year for all stages10,22).

The association between surgical approach (MIS vs open and robotic vs VATS) and short-term outcomes were evaluated with mixed-effect multivariable linear (LOS) and logistic (unplanned readmission, 30-day mortality, 90-day mortality) regression, with each model controlling for facility clustering. All models were adjusted for age (restricted cubic spline with knots at 47, 58, 65, 71, 79 years old), race, sex, insurance status, Charlson-Deyo comorbidity score, hospital volume (high volume vs nonhigh volume), preoperative therapy (chemotherapy/chemoradiation vs none), primary site (main bronchus vs other), margin status, and extended resection (defined using NCDB primary surgery codes 45, 46, 47, 48 for resection of chest wall, pericardium, diaphragm, and not otherwise specified).

Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to assess the association of surgical approach (MIS vs open and robotic vs VATS) with overall 5-year mortality. To reduce potential immortal time bias due to differences in treatment durations from those who received preoperative therapy and those who did not, patients who did not survive at least 6 months were excluded.23 This model controlled for the same factors as the short-term outcome models, plus receipt of any adjuvant therapy (defined as any systemic and/or radiation treatment after surgery).

Only cases with complete data for the primary exposure and covariates were included in the regression models. This was approximately 95% of the cases or more for each of the models. Patients diagnosed in 2016 were excluded from short- and long-term mortality analyses as these outcomes were not available for those patients in the Participant User File data. Power analyses were performed for the primary outcomes and confirmed at least 80% power or more to detect a hypothesized absolute risk reduction of 2% for short-term binary outcomes (30-day readmission, 30-day mortality, and 90-day mortality), 5% risk reduction for 5-year mortality, and a 1-day reduction in LOS. All analyses were performed in STATA v16.0 (College Station, TX). P values were considered significant at P < 0.05. The American College of Surgeons, Commission on Cancer, and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology used, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigators. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt.

RESULTS

From 2010 to 2016, 5741 patients met the inclusion criteria. There were 459 (8%) robotic, 1403 (24%) VATS, and 3879 (68%) open cases. Conversion to open occurred in 18% of all MIS cases, 9% for robotic cases and 20% for VATS cases (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Table 1 shows demographic, clinical, pathologic, and treatment information stratified by surgical approach. The groups were comparable in sex, race, and comorbidity distributions. Mean age was statistically different but clinically comparable as the largest difference was 1.2 years between groups (65 vs 63.8 years old for robotic vs open groups, respectively, P < 0.001). Patients who were uninsured were more likely to have an open procedure (78% open for uninsured compared to 69% and 66% for private and government insurance, respectively, P < 0.01). Similarly, those who had surgery at a nonacademic center were more likely to undergo an open procedure (71% and 63% in nonacademic vs academic centers, respectively, P < 0.001). Overall preoperative therapy (chemotherapy ± radiation) prevalence was 46% and did not differ by surgical approach (P = 0.27). Sixteen percent of patients received chemotherapy only, while 30% received chemoradiation. Patients in the open approach group had the lowest prevalence of having preoperative chemotherapy (14% in open, 20% in VATS, 24% in robotic, overall P < 0.001) but had the highest prevalence of preoperative chemoradiation (32% in open, 25% in VATS, 23% in robotic, P < 0.001). Of patients who underwent surgery, 48% received adjuvant therapy (47% open, 51% VATS, 47% robotic groups, overall P = 0.04). Additional tumor and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Treatment Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Lobectomy for Stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC, 2010–2016*

| MIS |

Open | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic | VATS | |||

|

| ||||

| Total, N | 459 (8) | 1403(25) | 3879 (68) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 65.0 (10) | 64.9 (10) | 63.8 (10) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.27 | |||

| Male | 217 (8) | 681 (24) | 1956 (69) | |

| Female | 242 (8) | 722 (25) | 1923 (67) | |

| Race, n (%) | 0.98 | |||

| White | 386 (8) | 1183(24) | 3271 (68) | |

| Black | 52 (8) | 154 (25) | 422 (67) | |

| Asian/PI/Other | 17(7) | 61 (25) | 163 (68) | |

| Charlson-Deyo, n (%) | 0.21 | |||

| 0 | 261 (8) | 759 (23) | 2223 (69) | |

| 1 | 137 (8) | 426 (25) | 1149 (67) | |

| 2 | 43 (8) | 151 (27) | 374 (66) | |

| 3+ | 18(8) | 67 (31) | 133 (61) | |

| Institution, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Nonacademic | 224 (7) | 704 (22) | 2295 (71) | |

| Academic | 232 (9) | 689 (28) | 1549 (63) | |

| Surgery at high-volume center§, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 388 (9) | 1120(26) | 2798 (65) | |

| No | 71 (5) | 283 (20) | 1081 (75) | |

| Region, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 102 (7) | 471 (32) | 919 (62) | |

| Midwest | 87 (6) | 250 (17) | 1104 (77) | |

| South | 233 (11) | 459 (22) | 1381 (67) | |

| West | 34 (5) | 213 (15) | 440 (64) | |

| Insurance, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Uninsured | 12 (10) | 14 (12) | 94 (78) | |

| Private | 176 (8) | 516 (23) | 1550 (69) | |

| Government | 263 (8) | 861 (26) | 2195 (66) | |

| Histology, n (%) | 0.04 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 13(11) | 27 (23) | 80 (67) | |

| Squamous cell | 113(7) | 384 (23) | 1181 (70) | |

| Large cell | 244 (8) | 765 (25) | 2008 (67) | |

| Other | 89 (10) | 227 (25) | 610 (66) | |

| Tumor size, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 0–2 cm | 126 (11) | 305 (27) | 712 (62) | |

| 2–3 cm | 106 (9) | 299 (24) | 826 (67) | |

| 3–5 cm | 137 (8) | 457 (25) | 1204 (67) | |

| 5–7 cm | 61 (7) | 208 (23) | 653 (71) | |

| >7 cm | 29 (5) | 134 (21) | 484 (75) | |

| Tumor grade, n (%) | <0.01 | |||

| Well differentiated | 39 (13) | 55 (19) | 197 (68) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 142 (8) | 453 (25) | 1225 (67) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 166 (7) | 583 (24) | 1661 (69) | |

| Undifferentiated | 11 (13) | 20 (23) | 55 (64) | |

| Not determined | 101 (9) | 292 (26) | 741 (65) | |

| Preoperative therapy†,ǁ, n (%) | 0.27 | |||

| Yes | 214 (47) | 620 (44) | 1810 (47) | |

| No | 245 (53) | 783 (56) | 2069 (53) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy onlyǁ, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 108 (24) | 276 (20) | 560 (14) | |

| No | 351 (76) | 1127(80) | 3319 (86) | |

| Preoperative chemoradiationǁ, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 106 (23) | 344 (25) | 1250 (32) | |

| No | 353 (77) | 1059(75) | 2629 (68) | 0.04 |

| Adjuvant therapy‡,ǁ, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 215(47) | 716 (51) | 1830 (47) | |

| No | 244 (53) | 687 (49) | 2049 (53) | 0.18 |

| Margins, n (%) | ||||

| Positive margins | 27 (6) | 103(23) | 315 (71) | |

| Negative margins | 431 (8) | 1288(25) | 3534 (67) | |

P values calculated by ANOVA testing for continuous variables and chi-squared for categorical variables. MIS, minimally invasive surgery; SD, standard deviation; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Row percentages are reported except otherwise noted.

Includes preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation.

Includes adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiation.

High volume defined as >20 lobectomies per year for any stage.

These variables show column percent.

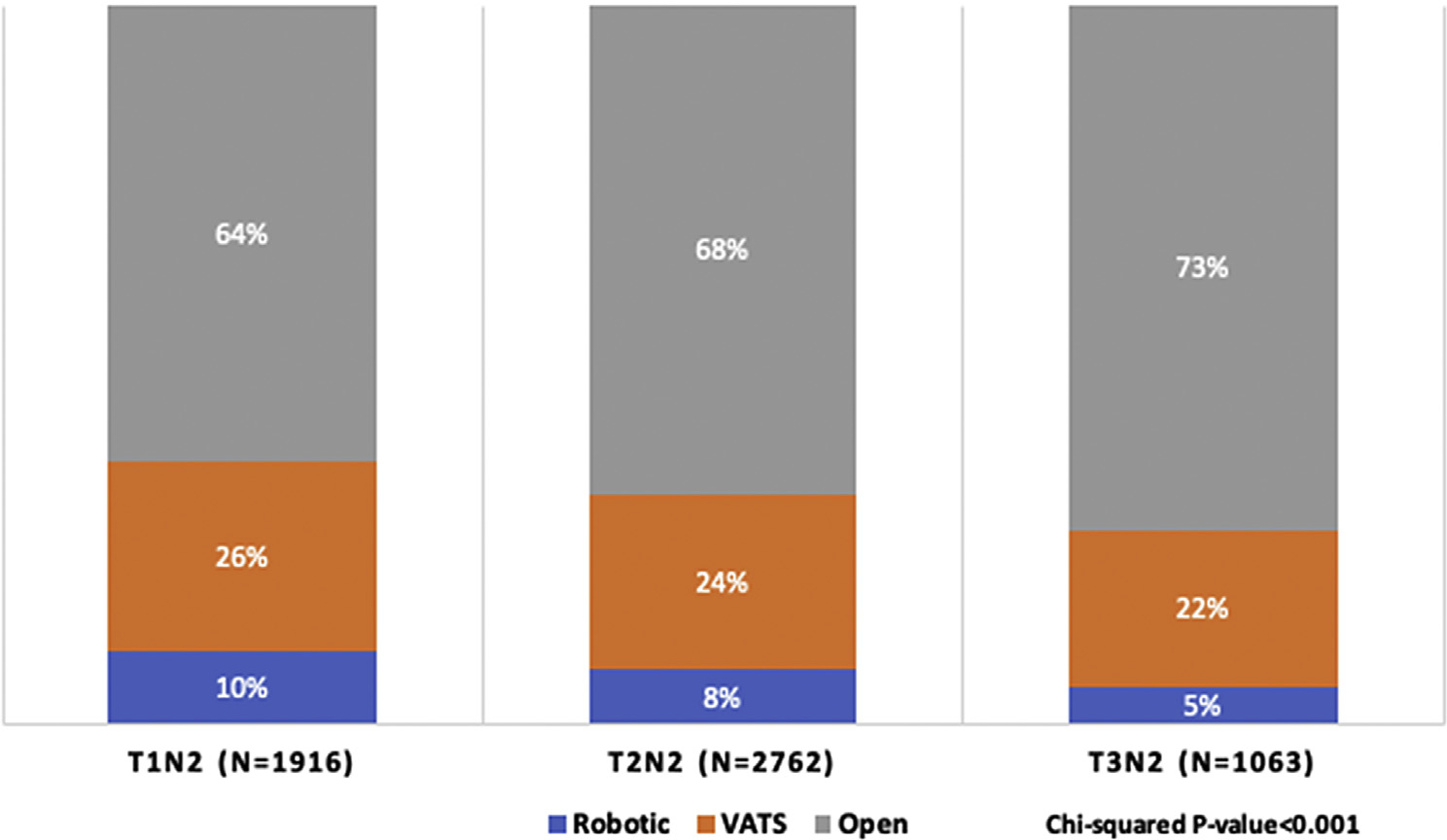

In general, the overall proportion of open lobectomies increased as T stage increased (P < 0.001, Fig. 1). The use of open surgery ranged from 64% to 73%, and was lowest for T1N2 disease and highest for T3N2 disease.

Figure 1.

Surgical approach for lobectomy by Stage IIIA N2 disease subtype, 2010–2016; each column displays the percentage of robotic, VATS, and open approaches for each TNM group of Stage IIIA-N2 disease (T1N2M0, T2N2M0, T3N2M0). For every TNM group, the most common was an open approach, followed by VATS and robotic. TNM, tumor node metastasis; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

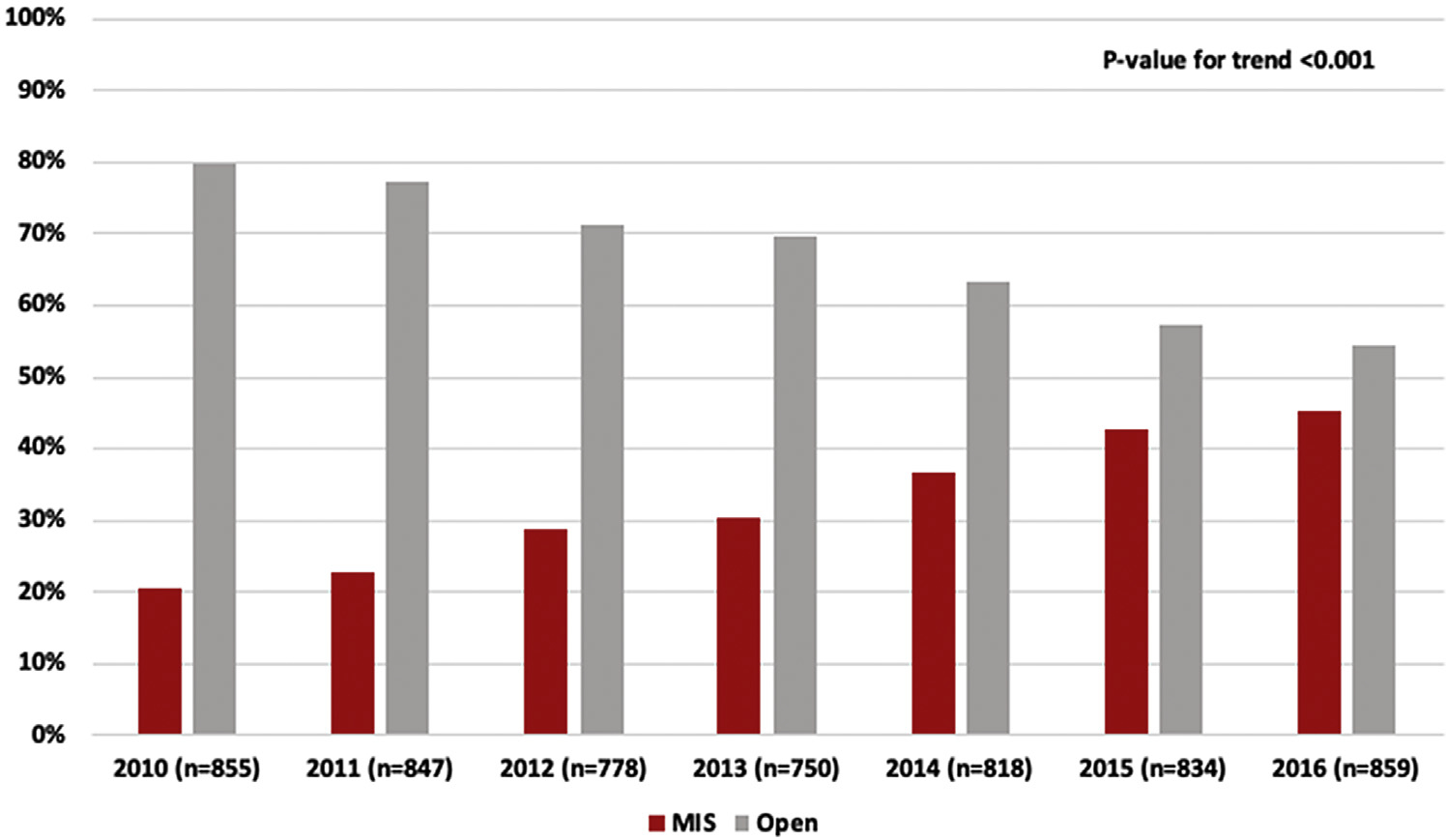

Over time, the percentage of MIS cases per year increased significantly from 20% in 2010 to 45% in 2016 (trend P value < 0.001; Fig. 2). Robotic approach increased from 3% to 14% and VATS approach increased from 18% to 32%. Finally, the percentage of MIS cases converted to open decreased over time from 38% to 17%. VATS conversions fell from 39% to 22% while the robotic conversion percent fell from 29% to 7% (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Trends in surgical approach to Stage IIIA N2 NSCLC, 2010–2016. Yearly percent of patients undergoing MIS and Open approaches are shown over the entire study period. The MIS approach increased significantly over time. MIS, minimally invasive surgery (video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic approach combined).

Table 2 shows the results of the outcomes analysis with unadjusted outcome frequencies for MIS and open followed by the adjusted mean difference and odds ratios (OR). Compared to open, the MIS group appeared to have lower odds of unplanned readmission (OR 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.57, 1.02), 30-day mortality (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.62, 1.27), and 90-day mortality (OR 0.79; 95% CI 0.60, 1.04), but estimates were not statistically significant. Average LOS was 1.3 days shorter (95% CI 0.9, 1.6) in the MIS vs open group. Five-year all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the MIS group compared to open (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.75, 0.91).

Table 2.

Overall Outcomes, MIS vs Open Lobectomy for Stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC, 2010–2016

| Incidence, N (%) |

OR (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MIS | Open | ||

|

| |||

| 30-day readmission | 73(4) | 160(4) | 0.97(0.71,1.33) |

| 30-day mortality | 31 (2) | 108 (3) | 0.73(0.48, 1.12) |

| 90-day mortality | 66 (5) | 217(7) | 0.74 (0.54, 0.99) |

| 5-year mortality | 525 (44) | 1376 (52) | 0.82 (0.75, 0.91)† |

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean Difference (95% CI)* | ||

| MIS | Open | ||

|

| |||

| Length of stay | 5.9 (5.5) | 7.1 (6.8) | −1.12 (−1.50, −0.74) |

CI, confidence interval; MIS, minimally invasive surgery; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation.

Adjusted for age, race, sex, insurance, Charlson-Deyo score, hospital volume, preoperative therapy, primary site, histology, tumor size, margin status, and extended resection; also adjusted for facility clustering.

Adjusted for all variables in footnote “*” (above) and adjuvant therapy.

When comparing robotic to VATS, we found that robotic was associated with significantly lower 90-day mortality (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.18, 0.97; Table 3). Patients who underwent robotic surgery, compared to VATS, may also have had lower 30-day mortality, but estimates were not statistically significant (OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.13, 1.40). There was no difference in 30-day readmission (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.53, 1.89), average LOS (mean difference: −0.5; 95% CI −1.2, 0.1) or 5-year mortality (OR 0.90; 95% CI 0.72, 1.12).

Table 3.

Overall Outcomes, Robotic vs VATS Lobectomy for Stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC, 2010–2016

| Incidence, N (%) |

OR (95% CI)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic | VATS | ||

|

| |||

| 30-day readmission | 15(3) | 58(4) | 0.99 (0.53, 1.89) |

| 30-day mortality | <10 | 27 (2) | 0.43 (0.13, 1.40) |

| 90-day mortality | <10 | 58 (5) | 0.42 (0.18, 0.97) |

| 5-year mortality | 112 (39) | 413 (45) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.12)† |

|

| |||

| Mean (SD) |

Mean Difference (95% CI)* | ||

| Robotic | VATS | ||

|

| |||

| Length of stay | 5.2 (5.1) | 6.1 (5.7) | -0.54 (-1.17,0.08) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SD, standard deviation; VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Adjusted for age, race, sex, insurance, Charlson-Deyo score, hospital volume, preoperative therapy, primary site, histology, stage category, margin status, and extended resection; also adjusted for facility clustering.

Adjusted for all variables in footnote ''*'' (above) and adjuvant therapy.

We performed a post hoc sensitivity analysis evaluating our primary outcomes (for MIS vs open and robotic vs VATS) for patients who received neoadjuvant therapy. These are reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Compared to the primary analysis, trends were similar but some results were not statistically significant, likely due to a reduction of our sample size by ~50%. There were still significantly lower odds of 5-year mortality and shorter LOS in the MIS compared to Open groups. Odds of 90-day mortality was not significantly lower in this analysis in contrast to the primary analysis. For robotic vs VATS, there was not a statistically significant reduction in 90-day mortality as in the primary analysis, and other outcomes remained not significantly different.

The average number of lymph nodes examined was significantly greater, although clinically similar, for MIS surgeries compared to open (14.1 vs 12.2, respectively; mean difference 95% CI 1.3, 2.4; Supplementary Table 3). Margin positivity rates were similar (7% MIS vs 8% open, chi-square P value 0.13). Both the number of lymph nodes examined (14.5 vs 13.9; P = 0.40) and margin positivity (6% vs 7%; P = 0.27) was similar between robotic and VATS. These findings were also consistent when we restricted to high-volume centers.

DISCUSSION

Prior studies have shown a majority of lobectomies for NSCLC are still performed by thoracotomy.6,10 This is especially true for locally advanced lung cancer for which 77–90% of cases were historically performed by thoracotomy.16,20,24 Our more current data show that this proportion is significantly declining with time with almost half of all cases performed by an MIS approach in 2016.

Few studies have directly compared the outcomes of MIS to open resection in locally advanced N2 NSCLC. All found a shorter LOS in the MIS group as well as no difference in mortality,16,17,20 and those that included complication rates found no difference.16,17 Our study extends this question to a large national cohort of patients with N2 disease from the NCDB. Additionally, our study adds on existing knowledge by including robotic resections. When comparing MIS to open surgery, this study also found a shorter LOS and similar short-term mortality. However, we found that patients undergoing MIS resection had lower overall 5-year mortality compared to the open group. This is consistent with the findings of a meta-analysis of early stage lung cancer by Yan et al that showed an improved 5-year mortality for VATS lobectomy.9 As discussed in Yan et al, our findings should also be taken with caution, as we cannot rule out the possibility that improved mortality for the MIS group was due to residual confounding rather than due to the surgical approach itself. Those in the MIS group may be predisposed to better long-term outcomes. Although we attempted to account for many factors that can affect long-term mortality, such as tumor size, preoperative/postoperative systemic therapies, hospital volume and between hospital variation, we could not account for all potential confounders. We did not have granular information on pulmonary functional and general functional status, extent of mediastinal staging, prior chest surgery, extent of N2 disease, or surgeon specific factors. Those with multistation N2 disease may be both more likely to undergo an open approach and also have worse mortality than single station N2 disease, which would bias results in favor of the minimally invasive approach.25,26 It is difficult to tease out the degree to which surgeon training and experience vs surgical technique contributes to outcomes. An MIS approach may be more often used by thoracic surgeons than general surgeons, and patients with lung cancer under the care of a thoracic surgeon have previously been shown to have improved outcomes.27 Even with these limitations, we believe our study shows that outcomes after an MIS approach are at least no different than open surgery for N2 disease. By using the NCDB, we have examined outcomes in a large national cohort of patients with surgically resected N2 disease. Smaller institutional-based studies may have more granular detail on potential confounders but are limited to the practice patterns/experience at that specific institution.

Few studies have directly compared robotic resections to VATS resections in locally advanced NSCLC. A recent meta-analysis of 14 studies which compared robotic vs VATS resections, primarily in early stage NSCLC, showed slightly lower 30-day mortality (0.7% vs 1.1%, respectively) and conversion to open rates (10.3% vs 11.9%, respectively). They found no differences in LOS, operative times, and nodal harvest.28 An analysis by Reddy et al, not included in the prior meta-analysis, compared robotic to VATS lobectomies among high-volume surgeons and showed a lower conversion rate (4.8% vs 8.0%, robotic vs VATS, respectively), lower incidence of 30-day complications, and similar 30-day mortality.22 One limitation of their study was a lack of staging data. Our analysis extends this comparison specifically to patients with locally advanced N2 disease. We find that robotic resections in this group are increasing with time consistent with what is happening for early stage lung cancer.15,29 We found no significant differences in nodal harvest, readmission rates, or LOS, but a lower conversion rate among patients undergoing robotic pulmonary resections. The improved conversion rate for robotic resections could be due to the features the robotic system, such as more degrees of articulation, scaled down movements, and magnified 3-dimensional views. On the other hand, it could also be due to patient selection as surgeons may select the most straightforward cases for the newer robotic approach. After controlling for factors such as preoperative therapy and hospital volume, the robotic approach was associated with a statistically significant lower odds of 90-day mortality. Given the higher conversion rate for the VATS approach and our intent to treat analysis, there may have been intraoperative factors not captured by the NCDB that led to higher 90-day mortality in the VATS group. Again, this may also be due to unmeasured factors but this finding is consistent with the prior studies in early stage lung cancer.

An additional finding was the surprisingly low number of patients undergoing preoperative systemic treatment in a population of patients undergoing resection for clinical stage IIIA-N2 NSCLC. We found 54% of patients with clinical stage N2 disease did not receive any preoperative therapy. One possibility is that many of these cases were incidental N2 disease where it is recommended to complete the resection if possible and then proceed with adjuvant therapy.30 We defined our cohort by the clinical staging criteria (ie, prior to surgery) and would expect a low number of incidental cases in this cohort. This finding of low rates of preoperative therapy is worth further study but highlights the controversies in surgical management of N2 disease.31–33 These findings may also represent disparities in guideline concordant care, and a more in-depth analysis of neoadjuvant therapy in this population, focusing on disadvantaged groups, is the subject of an ongoing project.

The most significant limitation of NCDB data is the potential for unmeasured confounding in this patient population. As previously discussed above, NCDB data lack the granular detail needed to ensure adequate adjustment for extent of disease and health history. Next, although there are data on overall survival, other important cancer outcomes such as disease-specific mortality and recurrence data were not available. Also, the cases in this cohort were staged by the AJCC seventh edition, thus inclusion criteria for our study population were slightly different than for patients currently diagnosed and staged using the eighth edition. Finally, only Commission on Cancer-accredited facilities are included and participation is voluntary, so results may not generalize to all hospitals.

In conclusion, we find that MIS compared to open thoracotomy for Stage IIIA-N2 lung cancer is associated with similar short-term outcomes and similar, or possibly even improved, overall 5-year survival Fig. 3. Robotic resections are increasing and appear to have improved perioperative outcomes compared to VATS, with similar overall 5-year survival. Although there are limitations (such as the potential for unmeasured confounding) in large observational studies, MIS approaches appear to be safe and effective compared to open surgery in highly select patients with Stage IIIA-N2 disease.

Figure 3.

Trends and outcomes in minimally invasive surgery for locally advanced NSCLC with N2 disease. Among patients with Stage IIIA N2 disease undergoing lobectomy, the use of MIS approach increased over time. Patients had better 90-day and 5-year survival in the MIS group compared to the open group, suggesting this approach is at least as safe as open surgery in this complex population. MIS, minimally invasive surgery (video-assisted thoracoscopic and robotic approach combined).

Supplementary Material

Central Message

Minimally invasive lobectomy for Stage IIIA N2 non\elsamp #x2013;small-cell lung cancer is increasing over time and is associated with at least similar short-term outcomes and better overall survival.

Perspective Statement

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery for early stage non\elsamp #x2013;small-cell lung cancer are well established, but few studies examine these benefits in operable N2 disease. We use the National Cancer Database and find minimally invasive vs open surgery is associated with similar short-term outcomes and better overall survival, highlighting its safety and effectiveness in N2 disease.

Funding:

Joshua Herb, MD: Dr Herb is partially supported by a National Service Research Award Pre-Doctoral/Post-Doctoral Traineeship from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality sponsored by the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, grant no. 5T32 HS000032.

Abbreviations:

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- MIS

minimally invasive surgery

- NCDB

National Cancer Database

- NSCLC

non–small-cell lung cancer

- TNM

tumor node metastasis

- VATS

video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Scanning this QR code will take you to the article title page to access supplementary information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Detterbeck FC, Lewis SZ, Diekemper R, et al. : Executive summary: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest; 143:7S–37S, 2013. 10.1378/chest.12-2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-small cell lung cancer (v2.2019). Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf. 2019. Accessed January 31, 2019

- 3.Hancock J, Rosen J, Moreno A, et al. : Management of clinical stage IIIA primary lung cancers in the National Cancer Database. Ann Thorac Surg 98:424–432, 2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan DS, Donington JS: The role of surgery in management of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 20:1–13, 2019. 10.1007/s11864-019-0624-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. : Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374:379–386, 2009. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60737-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang CF, Sun Z, Speicher P, et al. : Use and outcomes of minimally invasive lobectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer in the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Thorac Surg 101:1037–1042, 2016. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paul S, Altorki NK, Sheng S, et al. : Thoracoscopic lobectomy is associated with lower morbidity than open lobectomy: A propensity-matched analysis from the STS database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139:366–378, 2010. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boffa DJ, Dhamija A, Kosinski AS, et al. : Fewer complications result from a video-assisted approach to anatomic resection of clinical stage I lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 148:637–643, 2014. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.12.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, et al. : Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27:2553–2562, 2009. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kent M, Wang T, Whyte R, et al. : Open, video-assisted thoracic surgery, and robotic lobectomy: Review of a national database. Ann Thorac Surg 97:236–244, 2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zirafa CC, Cavaliere I, Ricciardi S, et al. : Long-term oncologic results for robotic major lung resection in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Surg Oncol 28:223–227, 2019. 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhi X, Gao W, Han B, et al. : VATS lobectomy facilitates the delivery of adjuvant docetaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 5:578–584, 2013. 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.02.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh DS, Reddy RM, Gorrepati ML, et al. : Robotic-assisted, video-assisted thoracoscopic and open lobectomy: Propensity-matched analysis of recent premier data. Ann Thorac Surg 104:1733–1740, 2017. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okusanya O, Lutfi W, Baker N, et al. : The association of robotic lobectomy volume and nodal upstaging in non-small cell lung cancer. J Robot Surg 14:709–715, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tchouta LN, Park HS, Boffa DJ, et al. : Hospital volume and outcomes of robot-assisted lobectomies. Chest 151:329–339, 2017. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park BJ, Yang HX, Woo KM, et al. : Minimally invasive (robotic assisted thoracic surgery and video-assisted thoracic surgery) lobectomy for the treatment of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 8(suppl 4):S406–S413, 2016. 10.21037/jtd.2016.04.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hennon M, Sahai RK, Yendamuri S, et al. : Safety of thoracoscopic lobectomy in locally advanced lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3732–3736, 2011. 10.1245/s10434-011-1834-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakanishi R, Fujino Y, Yamashita T, et al. : Thoracoscopic anatomic pulmonary resection for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 97:980–985, 2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.10.082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang CFJ, Adil SM, Anderson KL, et al. : Impact of patient selection and treatment strategies on outcomes after lobectomy for biopsy-proven stage IIIA pN2 non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 49:1607–1613, 2016. 10.1093/ejcts/ezv431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C-F, Nwosu A, Mayne NR, et al. : A minimally invasive approach to lobectomy after induction therapy does not compromise survival. Ann Thorac Surg 2019. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.09.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Cancer Database. American College of Surgeons Cancer Programs. Available at:https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb. 2019. Accessed March 1, 2020

- 22.Reddy RM, Gorrepati ML, Oh DS, et al. : Robotic-assisted versus thoracoscopic lobectomy outcomes from high-volume thoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg 106:902–908, 2018. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.03.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernán MA, Sauer BC, Hernandez-Díaz S, et al. : Specifying a target trial prevents immortal time bias and other self-inflicted injuries in observational analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 79:70–75, 2016. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen RP, Pham DK, Toloza EM, et al. : Thoracoscopic lobectomy: A safe and effective strategy for patients receiving induction therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 82:214–219, 2006. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho HJ, Kim SR, Kim HR, et al. : Modern outcome and risk analysis of surgically resected occult N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 97:1920–1925, 2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riquet M, Legras A, Mordant P, et al. : Number of mediastinal lymph nodes in non-small cell lung cancer: A Gaussian curve, not a prognostic factor. Ann Thorac Surg 98:224–231, 2014. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodney PP, Lucas FL, Stukel TA, et al. : Surgeon specialty and operative mortality with lung resection. Ann Surg 241:179–184, 2005. 10.1097/01.sla.0000149428.17238.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang H, Liang W, Zhao L, et al. : Robotic versus video-assisted lobectomy/segmentectomy for lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 268:254–259, 2018. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louie BE, Wilson JL, Kim S, et al. : Comparison of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and robotic approaches for clinical stage I and stage II non-small cell lung cancer using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Database. Ann Thorac Surg 102:917–924, 2016. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.03.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Detterbeck F: What to do with “Surprise” N2? Intraoperative management of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 3:289–302, 2008. 10.15845/nwr.v8i0.3502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanner NT, Gomez M, Rainwater C, et al. : Physician preferences for management of patients with stage IIIA NSCLC impact of bulk of nodal disease on therapy selection. 2012;7:365–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veeramachaneni NK, Feins RH, Stephenson BJK, et al. : Management of stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer by thoracic surgeons in North America. Ann Thorac Surg 94:922–928, 2012. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boffa DJ, Hancock JG, Yao X, et al. : Now or later: Evaluating the importance of chemotherapy timing in resectable stage III (N2) lung cancer in the National Cancer Database. Ann Thorac Surg 99:200–208, 2015. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.