Abstract

The ccoNOQP gene cluster of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T encodes a cbb3 cytochrome oxidase which is utilized in oxygen-limited conditions for aerobic respiration. The β-galactosidase activity of a ccoN::lacZ transcriptional fusion was low under high (30%)-oxygen and anaerobic growth conditions. Maximal ccoN::lacZ expression was observed when the oxygen concentration was lowered to 2%. In an FnrL mutant, ccoN::lacZ expression was significantly lower than in the wild-type strain, suggesting that FnrL is a positive regulator of genes encoding the cbb3 oxidase.

The ability of the facultative phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T to grow under oxygenic conditions is manifested by a branched respiratory chain consisting of at least three terminal oxidases (5). Under high-oxygen tensions the cytochrome aa3 oxidase, a member of the heme-copper family of oxidases, is the predominant cytochrome c oxidase (7). When the O2 concentration is low, the cbb3 oxidase is dominant (6). In addition to these two cytochrome c oxidases, R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T contains at least one quinol oxidase, as evidenced by the ability of cytochrome bc1 complex mutants to grow aerobically (19). At present, nothing is known about the quinol oxidase(s) of this organism, although we have recently discovered genes encoding two distinct quinol oxidases (11). Whether these genes encode functional oxidases which contribute to aerobic respiration is not yet known and is currently under investigation.

In contrast to the much-studied photosynthesis gene regulation in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T, relatively little is known about the regulation of genes encoding the terminal oxidases. A recent study described the regulation of the ctaD and coxII genes, which encode polypeptides of the aa3 oxidase (4). As predicted, the expression of these genes was repressed when cultures were grown microaerobically or anaerobically. This repression was only partly dependent on the FnrL protein, despite the presence of FnrL consensus motifs in the upstream regulatory sequences (URS) of these genes. From these results the authors concluded that an additional regulatory protein(s) may be involved in the regulation of aa3 oxidase expression.

It was shown in our laboratory that mutations in the ccoNOQP gene cluster, which encodes the cbb3 oxidase, lead to the induction of the photosynthetic apparatus under fully aerobic conditions (14, 23). Further, under strictly anaerobic conditions, a CcoP mutant strain was found to accumulate greatly increased levels of the carotenoid spheroidenone. These results suggested a role, in addition to oxidase activity, for the cbb3 oxidase in the generation of a redox signal for the regulation of photosynthesis gene expression. The results also suggested that the cco genes may be expressed under both aerobic and anaerobic growth conditions. Therefore, we were interested in examining the regulation of the cco gene cluster and how this might be related to the above phenotypic observations.

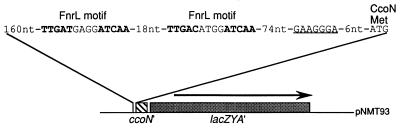

To investigate the expression of the cco gene cluster, we constructed a ccoN::lacZ transcriptional fusion from which we could measure β-galactosidase activity as a reporter of promoter activity. The URS of ccoN was amplified by the PCR with primers CCOP1 (5′-CGCGGATCCAAGCGCCAGCACGTCG-3′) and CCOP2 (5′-CGGAATTCGCGGCACACAGCGCG-3′), under conditions described previously (13). This generated a 380-bp product which was blunt ended with Pfu polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and cloned into the SmaI site of pUI1087 to generate pNMT82 (Table 1). The orientation and sequence of the cloned product were determined by DNA sequencing of both strands. The 410-bp BamHI-HindIII fragment containing the ccoN URS from pNMT82 was cloned into BamHI-HindIII-digested pML5 to generate plasmid pNMT93 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). pNMT93 was introduced into R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T (wild type) and JZ1678 (fnrL::Km) by conjugation to allow monitoring of ccoN::lacZ expression. Growth media and conditions, molecular biological methods, and suppliers of reagents were described previously (12). Aerobic cultures were sparged with 30% O2–69% N2–1% CO2 or 2% O2–97% N2–1% CO2 as described previously (14).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype and/or characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| R. sphaeroides | ||

| 2.4.1T | Wild-type | 17 |

| JZ1678 | ΔfnrL::ΩKmr | 22 |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5αphe | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA relA1 phe::Tn10dCm | 3 |

| HB101 | F− Δ(gpt-proA)62 leuB6 supE44 ara-14 glaK2 lacYI Δ(mcrC-mrr) rpsL20 (Str) xyl-5 mtl-1 recA13 | 1 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUI1087 | Cloning vector | 21 |

| pBS II | Cloning vector, Ampr, with T3 and T7 promoters | Stratagene |

| pML5 | Promoterless lacZ transcriptional fusion vector, Tcr | 10 |

| pNMT82 | pBS II containing 380-bp ccoN′ PCR product | This study |

| pNMT93 | pML5 containing ccoN::lacZ | This study |

FIG. 1.

Physical map of plasmid pNMT93 containing the ccoN::lacZ transcriptional fusion. The two sequences with significant identity to the Fnr consensus sequenced are indicated in boldface. The putative Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of the CcoN initiation codon is underlined. See the text for further details.

ccoN expression is regulated by oxygen concentration.

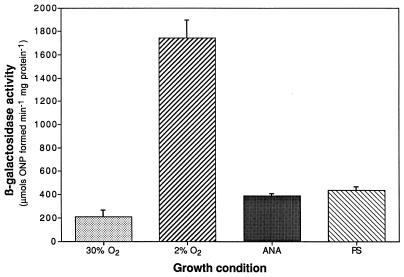

By assaying β-galactosidase activities, as described previously, of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T containing pNMT93, the expression of ccoN::lacZ was measured from cultures grown under different conditions (16). It was previously shown that the copy number of plasmids with an RSF1010 replicon, such as pML5, is four to six in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T and does not vary with growth condition, and thus, our interpretation of these results is not likely to be affected by plasmid copy number (16). Under high (30%)-oxygen conditions, the expression of ccoN::lacZ was low (Fig. 2). An approximately ninefold increase in activity was observed after growth in the presence of 2% oxygen. After anaerobic growth in the dark with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as the terminal electron acceptor or after photosynthetic growth, an approximately twofold increase in ccoN::lacZ activity was observed when compared to levels observed after growth with a high oxygen concentration. The high level of ccoN expression under microaerophilic (2% oxygen) growth conditions is in accordance with the proposed role for the cbb3 oxidase as a high-affinity oxidase since expression of the oxidase genes should be maximal under these growth conditions. The reduction of ccoN::lacZ activity observed in cultures grown strictly anaerobically versus the activity observed for microaerophilic growth is intriguing and suggests that both negative and positive control mechanisms are present. In Escherichia coli, genes for the cytochrome bd high-affinity oxidase are induced via the ArcBA sensor-regulator system under microaerobic conditions and repressed under strictly anaerobic conditions via Fnr (2).

FIG. 2.

β-Galactosidase activities from cell extracts of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T containing the ccoN::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid pNMT93. Growth conditions are as follows: aerobically with 30% (░⃞) or 2% (▨) oxygen, anaerobically (ANA) (▩) in the dark with 60 mM DMSO, and photosynthetically (PS) (▧). Results are the mean values from triplicate assays of at least two independent cultures. Vertical bars represent the standard deviation from the mean.

The FnrL protein is a positive regulator of ccoN expression.

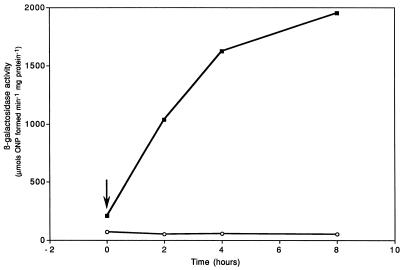

Examination of the ccoN URS revealed the presence of two sequences which show almost perfect identity to the proposed Fnr consensus motif sequence (TTGAT-N4-ATCAA) (Fig. 1) (15). This suggested that the Fnr homolog of R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T, FnrL, may be involved in the regulation of ccoN expression. It has also been shown that the Fnr homolog in Paracoccus denitrificans, FnrP, is required for ccoNOQP expression in this bacterium (18). In order to determine whether FnrL regulates cco expression, the ccoN::lacZ fusion plasmid pNMT93 was introduced into the FnrL mutant strain JZ1678 (22). Since this FnrL mutant is unable to grow either anaerobically in the dark with DMSO or photosynthetically, we elected to perform an oxygen shift experiment where cultures grown with 30% oxygen were shifted to 2% oxygen to approximate a shift to anaerobiosis. At the time intervals indicated, samples were removed and their β-galactosidase activities were assayed as described previously (22).

In the wild-type strain, 2.4.1T, the levels of ccoN::lacZ expression increased steadily after the cultures were shifted to 2% oxygen (Fig. 3). Up to 8 h postshift, the levels of ccoN::lacZ expression had not reached a steady-state level. In contrast, activity of ccoN::lacZ in the FnrL mutant remained at less than the wild-type uninduced level at all the time points assayed. This indicates an absolute requirement for FnrL, either directly or indirectly, for the induction of ccoN expression in response to the lowering of oxygen tension in the medium. The presence of Fnr consensus motifs in the ccoN URS raises the possibility that Fnr acts directly at the ccoN promoter to activate ccoN expression. Further, the unusual arrangement of the motifs, i.e., the fact that they are separated by only 18 bp, suggests that two FnrL dimers are able to bind close to each other on the same face of the DNA helix. A similar arrangement of Fnr motifs was found in the ansB promoter of E. coli, but it was demonstrated that only the downstream motif was required for Fnr-dependent regulation (9). It will be of interest to examine the requirement of each of the two motifs for FnrL-mediated regulation of ccoN expression in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of induction of ccoN::lacZ expression from the ccoN::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid pNMT93 in the wild-type strain, 2.4.1T (▪), and FnrL mutant strain JZ1678 (○) following a shift from 30 to 2% oxygen (indicated by the vertical arrow). Cultures were sampled at the times indicated, and extracts from 15-ml samples were assayed for β-galactosidase activity. The values represent the means of triplicate assays from two independent growth experiments. The standard error in each case did not exceed 20% of the mean value.

Interestingly, after high-oxygen growth the activity of ccoN::lacZ in the FnrL mutant was approximately 50% of that in the wild-type strain, suggesting that the FnrL protein retains some activity under oxygen-rich conditions in this bacterium. Previously, it was observed that the FnrL mutant was affected in hemA expression under strictly aerobic conditions (22). It has been suggested that the presence of a histidine residue at position 29 and an alanine residue at position 154 in the FnrL sequence in the R. sphaeroides protein may allow this protein to dimerize and hence be active under aerobic conditions (22). The basal level of ccoN::lacZ activity which remains in the FnrL mutant background may be indicative of a second FnrL-independent cco promoter. It would therefore be interesting to examine the transcript starts of the ccoNOQP gene cluster under different growth conditions to see whether this is indeed the case.

Conclusions.

These results are the first to demonstrate that the ccoN gene in R. sphaeroides is regulated in response to oxygen concentration. Maximal expression of ccoN::lacZ was observed after growth with 2% oxygen, although the physiological oxygen concentration required for maximum expression is unknown. We show here that the induction of ccoN expression upon a shift to microaerobic conditions from oxygen-rich conditions is dependent on the FnrL protein. Since the FnrL protein must be active under strictly anaerobic conditions (as an FnrL mutant is unable to grow anaerobically) the observation that ccoN::lacZ expression was reduced after anaerobic growth, when compared to growth under 2% oxygen, was surprising. Whether the FnrL protein plays a repressor role, in addition to its activating function, is unclear. It is interesting that in the closely related Rhodobacter capsulatus an FnrL mutant was not affected in the accumulation of the CcoO and CcoP c-type cytochromes or in the ability to grow photosynthetically (20). Further, given that FnrL is only partly responsible for the repression of genes encoding the aa3 oxidase in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1T in response to lowered oxygen tension, it is speculative to suggest that there are multiple regulatory pathways for the control of genes encoding cytochrome oxidases in Rhodobacter spp.

This study supports the previous work of O’Gara and Kaplan, who found that CcoP mutants had a phenotype under both high-oxygen and strictly anaerobic growth conditions (14). The authors suggest that an additional role of the cbb3 oxidase is to serve as a component of a redox-active signal transduction pathway to affect photosynthesis gene expression in response to changes in oxygen availability. This is currently under further investigation in our laboratory. Although maximal ccoN expression was observed only under 2% oxygen, the relatively lower levels of expression seen under high-oxygen and anaerobic conditions must be sufficient for this putative signalling role. This suggests that as the oxygen tension decreases, the increase in ccoN expression is required for a functional high-affinity oxidase but that a low basal level of oxidase is sufficient for its putative signalling role. Clearly, further studies are required to determine the nature of this redox signal. In relation to this, it is interesting to note the requirement of low levels of the cytochrome bo and cytochrome bd oxidases in E. coli for the activity of the ArcBA sensor-regulator pathway in the control of the genes encoding both oxidases (8). Perhaps a low level of oxidase production is sufficient for the generation of a redox signal but insufficient for terminal oxidase function. Further experiments should shed light on the true nature of the proposed redox signalling function for these oxidases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jill Zeilstra-Ryalls for helpful discussion and technical assistance with the oxygen shift experiment.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM15590 (to S.K.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cotter P A, Melville S B, Albrecht J A, Gunsalus R P. Aerobic regulation of cytochrome d oxidase (cydAB) operon expression in Escherichia coli: roles of Fnr and ArcA in repression and activation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:605–615. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5031860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eraso J M, Kaplan S. prrA, a putative response regulator involved in oxygen regulation of photosynthesis gene expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:32–43. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.32-43.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flory J E, Donohue T J. Transcriptional control of several aerobically induced cytochrome structural genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Microbiology. 1997;143:3101–3110. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Horsman J A, Barquera B, Rumbley J, Ma J, Gennis R B. The superfamily of heme-copper respiratory oxidases. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5587–5600. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5587-5600.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Horsman J A, Berry E, Shapleigh J P, Alben J O, Gennis R B. A novel cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroidesthat lacks CuA. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3113–3119. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosler J P, Fetter J, Tecklenberg M M J, Espe M, Lerma C, Ferguson-Miller S. Cytochrome aa3 of Rhodobacter sphaeroides as a model for mitochondrial cytochrome coxidase: purification, kinetics, proton pumping and spectral analysis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:24264–24272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iuchi S, Chepuri V, Fu H-A, Gennis R B, Lin E C C. Requirement for terminal cytochromes in generation of the aerobic signal for the arc regulatory system in Escherichia coli: study utilizing deletions and lac fusions of cyo and cyd. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6020–6025. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.6020-6025.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings M P, Beacham I R. Co-dependent positive regulation of the ansB promoter of Escherichia coliby CRP and the FNR protein: a molecular analysis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labes M, Pühler A, Simon R. A new family of RSF1010-derived expression and lac-fusion broad-host-range vectors for gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1990;89:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouncey, N. J., M. Choudhary, and S. Kaplan. Unpublished observations.

- 12.Mouncey N J, Choudhary M, Kaplan S. Characterization of genes encoding dimethylsulfoxide reductase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T: an essential metabolic gene function encoded on chromosome II. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7617–7624. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.24.7617-7624.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mouncey, N. J., and S. Kaplan. Cascade regulation of dimethyl sulfoxide reductase (dor) gene expression in the facultative phototroph, Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1T. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.O’Gara J P, Kaplan S. Evidence for the role of redox carriers in photosynthesis gene expression and carotenoid biosynthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1951–1961. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.6.1951-1961.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spiro S, Guest J R. FNR and its role in oxygen-regulated gene expression in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;75:399–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tai T-N, Havelka W A, Kaplan S. A broad host-range vector system for cloning and translational lacZfusion analysis. Plasmid. 1988;19:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(88)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Neil C B. The culture, general physiology, morphology, and classification of the non-sulfur purple and brown bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1944;8:1–118. doi: 10.1128/br.8.1.1-118.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Spanning R J M, De Boer A P N, Reijnders W N M, Westerhoff H V, Stouthamer A H, Van Der Oost J. FnrP and NNR of Paracoccus denitrificansare both members of the FNR family of transcriptional activators but have distinct roles in respiratory adaptation in response to oxygen limitation. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:893–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2801638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yun C-H, Beci R, Crofts A R, Kaplan S, Gennis R B. Cloning and DNA sequencing of the fbc operon encoding the cytochrome bc1 complex from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Eur J Biochem. 1990;194:399–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeilstra-Ryalls J H, Gabbert K, Mouncey N J, Kaplan S, Kranz R G. Analysis of the fnrL gene and its function in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7264–7273. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7264-7273.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeilstra-Ryalls J H, Kaplan S. Regulation of 5-aminolevulinic acid synthesis in Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.1: the genetic basis of mutant H-5 auxotrophy. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2760–2768. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2760-2768.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeilstra-Ryalls J H, Kaplan S. Aerobic and anaerobic regulation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides 2.4.1: the role of the fnrLgene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6422–6431. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6422-6431.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeilstra-Ryalls J H, Kaplan S. Control of hemA expression in Rhodobacter sphaeroides2.4.1: regulation through alterations in the cellular redox state. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:985–993. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.4.985-993.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]