Abstract

One of the most puzzling results from the complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus jannaschii was that the organism may have only one DNA polymerase gene. This is because no other DNA polymerase-like open reading frames (ORFs) were found besides one ORF having the typical α-like DNA polymerase (family B). Recently, we identified the genes of DNA polymerase II (the second DNA polymerase) from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus, which has also at least one α-like DNA polymerase (T. Uemori, Y. Sato, I. Kato, H. Doi, and Y. Ishino, Genes Cells 2:499–512, 1997). The genes in M. jannaschii encoding the proteins that are homologous to the DNA polymerase II of P. furiosus have been located and cloned. The gene products of M. jannaschii expressed in Escherichia coli had both DNA polymerizing and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities. We propose here a novel DNA polymerase family which is entirely different from other hitherto-described DNA polymerases.

DNA polymerases play leading roles in cellular DNA replication and repair. They can be classified into four major groups based on amino acid sequences (8). Family A includes the most abundant DNA polymerases in eubacterial cells, such as Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Pol I). All of the replicative DNA polymerases from eucaryotic and eubacterial cells belong to families B and C, respectively. Family X consists of eucaryotic DNA polymerase β and terminal transferases.

The domain Archaea is now recognized as constituting a third major branch of life, together with Bacteria (eubacteria) and Eucarya (eucaryotes) (17). Archaeal proteins involved in gene expression, such as those for DNA replication, transcription, and translation, have been found to be similar to those from Eucarya, although the cellular appearance and organization of Archaea are more like those of Bacteria. All of the sequences of the archaeal DNA polymerases thus far are classified as α-like (family B) DNA polymerases. Among them, two hyperthermophilic archaea, Pyrodictium occultum and Sulfolobus solfataricus, possess two (14) and three (5) α-like DNA polymerase genes, respectively, although it has not been proved whether two of the three genes in S. solfataricus are expressed to produce active DNA polymerases. This finding tempted us to speculate that the DNA replication machinery in Archaea may be a prototype of the eucaryotic machinery, because three α-like DNA polymerases (α, δ, and ɛ) function in eucaryotic DNA replication (reviewed in reference 1).

The first complete sequence of an archaeal genome, from Methanococcus jannaschii, which is a methane-producing archaeon, was published in 1996 (2). Surprisingly, it was found that this genome includes only one open reading frame with a sequence homologous to α-like DNA polymerases and lacks other DNA polymerase sequences. One of the most controversial issues from the first complete genome sequence from Archaea is whether this organism indeed possesses only one DNA polymerase (3, 4, 6, 11). More definitely, it would be very surprising if the life of this archaeon were dominated by only a single DNA polymerase with a unique mechanism, since it is well established that both eucaryotic and eubacterial cells contain several DNA polymerases involved in replication and repair.

Search for homologs of Pyrococcus furiosus DP1 and DP2.

Recently, we found novel DNA polymerase genes in the hyperthermophilic archaeon P. furiosus, which encode a product that is completely distinct from any other known DNA polymerase (16). This DNA polymerase is composed of two different polypeptides, DP1 (69 kDa) and DP2 (143 kDa). We have searched the complete genome sequence of M. jannaschii and have found two open reading frames, MJ0702 and MJ1630, with sequences that are highly homologous to the two subunits of P. furiosus, i.e., DP1 (40%) and DP2 (60%), respectively (Fig. 1). We cloned the two genes from the total DNA of M. jannaschii by PCR and constructed an expression system with the pET21a plasmid (Novagen). The resultant plasmids were designated pMJDP1 and pMJDP2, respectively.

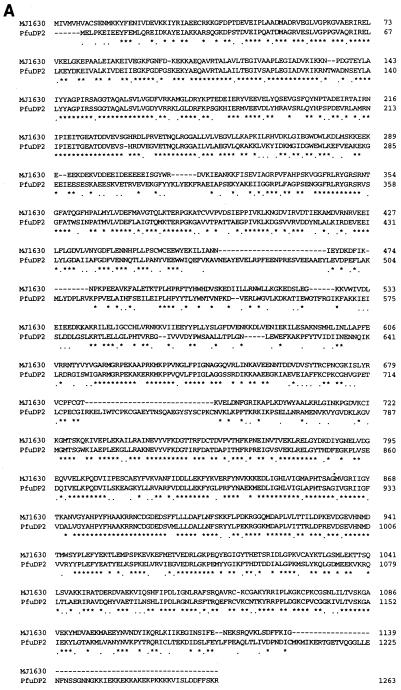

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the two components of DNA Pol II from P. furiosus and M. jannaschii. (A and B) DP2 and DP1, respectively. CLUSTAL W (13) was used for sequence alignment of the two polymerases. Identical and similar amino acid residues at the same positions are indicated by asterisks and dots, respectively, in both alignments.

Identification of DNA polymerase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activity.

Sonicated cell extracts from E. coli BL21(DE3), carrying either plasmid pMJDP1 or pMJDP2, were heat treated at 80°C for 15 min to inactivate the DNA polymerase activities from the host E. coli cells. Then, the DNA polymerase activity at 65°C was measured with these extracts (heated extract [HE]). The reaction mixtures contained, in 40 μl, 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mg of calf thymus activated DNA per ml, 40 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) containing 60 nM [methyl-3H]TTP, and protein samples and were incubated at 65°C for 10 min. The results demonstrated that the radioactivity was incorporated into acid-insoluble fraction only by the mixture of two extracts from BL21(DE3)/pMJDP1 (HE1) and BL21(DE3)/pMJDP2 (HE2). Neither extract exhibited the incorporation activity individually (Fig. 2A). To prove its DNA polymerizing activity more definitively, a chain elongation assay was done with a single-stranded DNA (prepared from plasmid p240C, which has an insert of 40 bp, dCGATAAGGGCAACGAATCCATGTGGAGAAGAGCCTCTATA, at the HincII site of pUC118) annealed with a 32P-labeled d40-mer with the above sequence as a template primer in a reaction mixture containing 20 mM Tris HCl (pH 8.8), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 83 μM dNTPs. As shown in Fig. 2B, the 32P-labeled primer was extended by the combined extract (HE1-HE2), even though the degradation of the primer was faster. The 3′→5′ exonuclease activity was also investigated. The 32P-labeled d40-mer was used as a substrate directly (for single-stranded substrate) or after being annealed with p240CS single-stranded DNA (for double-stranded substrate) and was incubated with the proteins in the reaction mixture described above without dNTPs. The 3′→5′ exonuclease activity was also detected only when the two extracts were mixed (Fig. 3). Therefore, we conclude that the mixture of the two gene products (69 and 129 kDa) is essential for the emergence of the DNA polymerase and 3′→5′ exonuclease activities, just as in the case of P. furiosus. These two genes were designated polB and polC, respectively, and the gene products were designated M. jannaschii Pol II (M. jannaschii has a gene encoding a protein with the sequence of typical α-like DNA polymerases as described above) according to the corresponding genes and their products in P. furiosus (16).

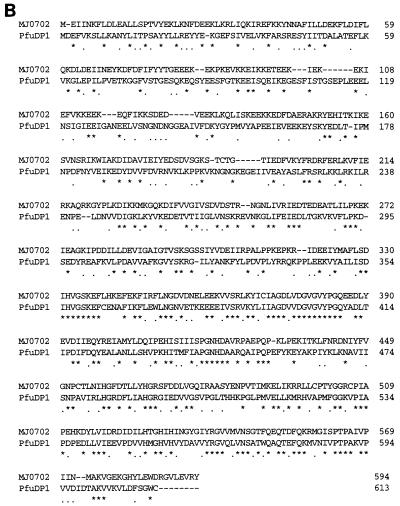

FIG. 2.

Detection of the DNA polymerizing activity from the MJ0702 and MJ1630 proteins. The reaction conditions are described in the text. (A) The acid-insoluble radioactivity bound to DE 81 paper detected by a scintillation counter. Protein samples are indicated under the bar graph as follows: EHE, HE from BL21(DE3)/pET21a; DP1, HE from BL21(DE3)/pMJDP1; DP2, HE from BL21(DE3)/pMJDP2. Lanes 1 and 5, H2O; lane 2, 14 μg; lanes 3 and 4, 7.0 μg each; lane 6, 1.75 μg each; lane 7, 3.5 μg each; lane 8, 5.25 μg each; lane 9, 7.0 μg each; lanes 10 to 14, DP1 (7.0 μg) and various amounts of DP2 (lane 10, 0 μg; lane 11, 1.75 μg; lane 12, 3.5 μg; lane 13, 5.25 μg; and lane 14, 7.0 μg). (B) Chain elongation ability detected by a primer extension reaction with a single-stranded DNA annealed with a 32P-labeled d40-mer (described in the text) as a template primer. Equal amounts were sampled at 2, 5, 10, and 15 min from the reaction mixture and loaded onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. The electrophoretic profile was visualized by autoradiography.

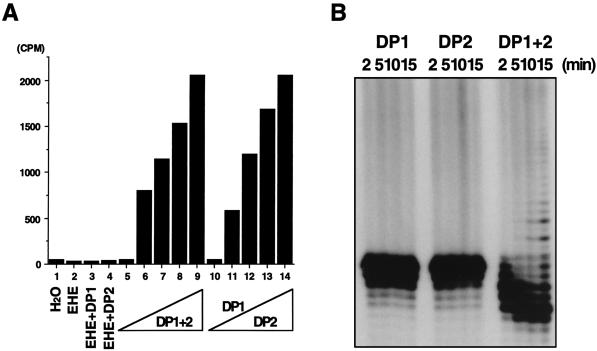

FIG. 3.

Detection of the 3′→5′ exonuclease activity from the MJ0702 and MJ1630 proteins. For the 3′→5′ exonuclease assay, equal aliquots of the reaction mixture described in the text were removed after 2, 5, 10, and 15 min and were added to a stop solution. Products were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of 8 M urea as described for Fig. 2B. ds, double stranded; ss, single stranded.

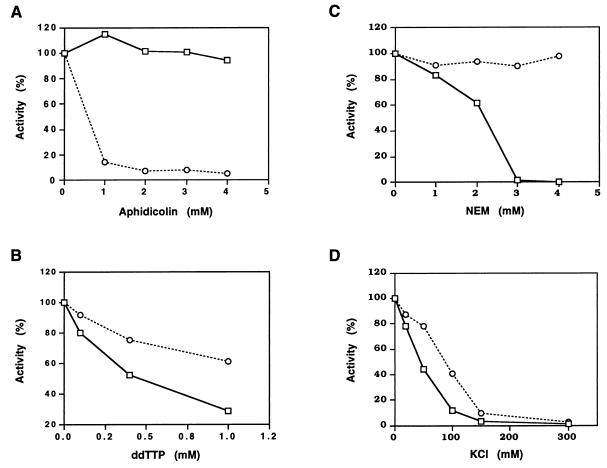

Inhibition analysis of the DNA polymerase activity.

The inhibition mode of the DNA polymerizing activity of M. jannaschii Pol II was investigated by using representative inhibitors of DNA polymerases. Aphidicolin did not inhibit the activity of M. jannaschii Pol II with the concentration that inhibited P. furiosus Pol I, an α-like DNA polymerase (15). Instead, M. jannaschii Pol II was more sensitive to ddTTP, N-ethylmaleimide, and salt than was P. furiosus Pol I (Fig. 4). These characteristics are the same as those of P. furiosus Pol II (7), and this pattern is different from that of other known DNA polymerases (10).

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of the DNA polymerizing activity of M. jannaschii Pol II (DP1-DP2) by aphidicolin, ddTTP, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and salt. The standard assay mixture containing [methyl-3H]TTP for DNA polymerizing activity as described in the text was processed in the presence of the indicated amounts of inhibitors. Acid-insoluble radioactivities were counted with a scintillation counter. The open squares and circles indicate M. jannaschii Pol II and P. furiosus Pol I, respectively.

A new DNA polymerase family in Archaea.

We have also detected genes within Pyrococcus woesei that encode proteins homologous to DP1 and DP2 (unpublished data). Therefore, we now propose a new DNA polymerase family, which is characterized by archaeal heterodimeric DNA polymerases. The functional properties, such as a concomitant strong 3′→5′ exonuclease activity and an excellent primer extension ability (16), suggest that the DNA polymerases belonging to this family may play a crucial role in DNA replication. In comparison with the excellent primer elongation ability in vitro of P. furiosus Pol II in our previous report with the purified proteins (16), the ability of M. jannaschii Pol II (HEs from recombinant E. coli strains) in this study was very poor. The possibility that some inhibitor is included in the HE or that M. jannaschii Pol II may need some auxiliary proteins for its maximal processivity has to be addressed. This new DNA polymerase found in the two archaea shows no sequence homology to those of any other families. Therefore, it is possible that the catalytic center of this DNA polymerase comprises two separate gene products, which differs from the previous findings that all DNA polymerases contain their own definite catalytic centers in single polypeptides. We can also envisage a situation where the auxiliary component activates a novel type of catalytic subunit by a conformational change, removal of a repressor, or some other mode. As we continue to investigate this DNA polymerase, the mechanism will be unravelled.

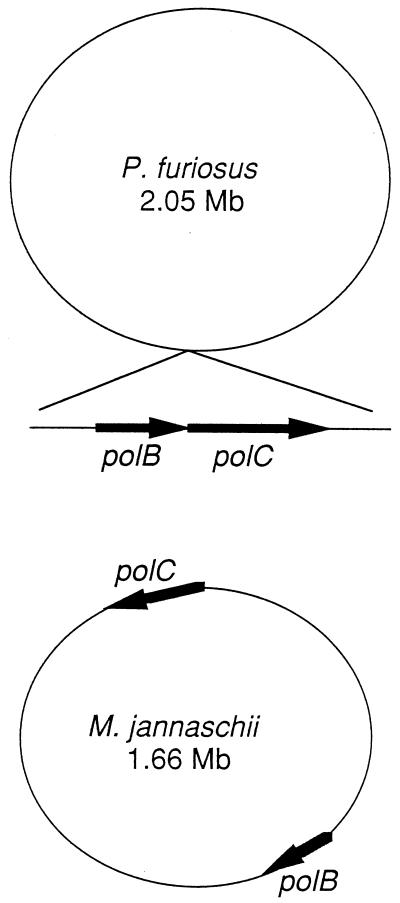

The gene organization of the components of the new polymerase is also very interesting. The two responsible genes are arranged in tandem and constitute an operon in both P. furiosus and P. woesei. In contrast, the two genes are completely separated in the genome of M. jannaschii (Fig. 5). It is advantageous to coordinate the expression of the two genes for adjustment of the amount of the two components of Pol II in the cells, and therefore, it is intriguing to imagine how the gene expression of Pol II is regulated in M. jannaschii.

FIG. 5.

Localization of the two genes corresponding to the new DNA polymerase in the genomes of P. furiosus and M. jannaschii. The locations of the genes in M. jannaschii follow the published map. The location of the P. furiosus operon is indeterminate, due to the absence of a complete genomic sequence.

At the moment, most studies of DNA replication are concentrated on the initiation stage in both Bacteria and Eucarya. Although these studies have provided many important insights into the roles of the proteins in the DNA replication process, there are still many problems to be elucidated with respect to the complicated molecular mechanisms of DNA replication, such as how the various DNA polymerases share their roles in DNA synthesis. A BLAST search for homologs in the current databases did not reveal any protein or open reading frame with significant similarity to either MJ0702 or MJ1630; however, some proteins related to DNA replication with local similarities were listed as described in the study of P. furiosus (16). Two more complete genome sequences from the archaeal domain were published very recently, and we have found the homologs of DP1 and DP2 in the genomes of these organisms, Archaeoglobus fulgidus (9) and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum (12). We now have the opportunity to analyze the sequences of the four archaeal proteins in detail and may be able to predict some motifs including critical residues for polymerizing and nucleolytic activities from the comparison with other known polymerases. Our finding of this novel DNA polymerase family in Archaea should contribute to a better understanding of the functional and evolutionary aspects of the replication machineries in the three branches of life.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kosuke Morikawa for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brush G S, Kelly T J. Mechanisms for replicating DNA. In: DePamphilis M L, editor. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Presley E A, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Hurst M A, Roberts K M, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edgell D R, Doolittle W F. Archaebacterial genomics: the complete genome sequence of Methanococcus jannaschii. Bioessays. 1996;19:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edgell D R, Doolittle W F. Archaea and the origin(s) of DNA replication proteins. Cell. 1997;89:995–998. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80285-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edgell D R, Klenk H-P, Doolittle W F. Gene duplications in evolution of archaeal family B DNA polymerases. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2632–2640. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2632-2640.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray M W. The third form of life. Nature. 1996;383:299. doi: 10.1038/383299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imamura M, Uemori T, Kato I, Ishino Y. A non-α-like DNA polymerase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Biol Pharm Bull. 1995;18:1647–1652. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito J, Braithwaite D K. Compilation, alignment, and phylogenetic relationships of DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4045–4057. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.4.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klenk H P, Clayton R A, Tomb J, White O, Nelson K E, Ketchum K A, Dodson R J, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Peterson J D, Richardson D L, Kerlavage A R, Graham D E, Kyrpides N C, Fleischmann R D, Quackenbush J, Lee N H, Sutton G G, Gill S, Kirkness E F, Dougherty B A, McKenney K, Adams M D, Loftus B, Peterson S, Reich C I, McNeil L K, Badger J H, Glodek A, Zhou L, Overbeek R, Gocayne J D, Weidman J F, McDonald L, Utterback T, Cotton M D, Spriggs T, Artiach P, Kaine B P, Sykes S M, Sadow P W, D’Andrea K P, Bowman C, Fujii C, Garland S A, Mason T M, Olsen G J, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the hyperthermophilic, sulphate-reducing archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Nature. 1997;390:364–370. doi: 10.1038/37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman and Co.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morell V. Life’s last domain. Science. 1996;273:1043–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H-M, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Safer H, Patwell D, Prabhakar S, McDougall S, Shimer G, Goyal A, Pietrokovski S, Church G M, Daniels C J, Mao J-I, Rice P, Nolling J, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;11:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uemori T, Ishino Y, Doi H, Kato I. The hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrodictium occultum has two α-like DNA polymerases. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2164–2177. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2164-2177.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uemori T, Ishino Y, Toh H, Asada K, Kato I. Organization and nucleotide sequence of the DNA polymerase gene from the archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:259–265. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.2.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uemori T, Sato Y, Kato I, Doi H, Ishino Y. A novel DNA polymerase in the hyperthermophilic archaeon, Pyrococcus furiosus; gene cloning, expression, and characterization. Genes Cells. 1997;2:499–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1997.1380336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woese C R, Kandler O, Wheelis M L. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains archaea, bacteria, and eukarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]