Rates of obesity, hypertension, and high cholesterol levels are high, but most have no health insurance

California's agricultural workers have little access to health care and high rates of obesity, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. There is an obvious irony in the fact that this group of workers is responsible for growing and gathering much of our food supply, but their own diets and health status are poor.

Much of what we know about farm workers' health comes from the California Agricultural Workers Health Survey, conducted by the California Institute for Rural Studies.1 Eighty percent of workers surveyed had no health insurance whatsoever. Perhaps we should not be surprised, given the predominantly seasonal, part-time nature of their employment and the extremely competitive and cost-conscious pressures within the food industry. In addition, 34% of workers said that they were undocumented immigrants, which makes them ineligible for Medi-Cal (California's Medicaid) or other forms of publicly supported health insurance.

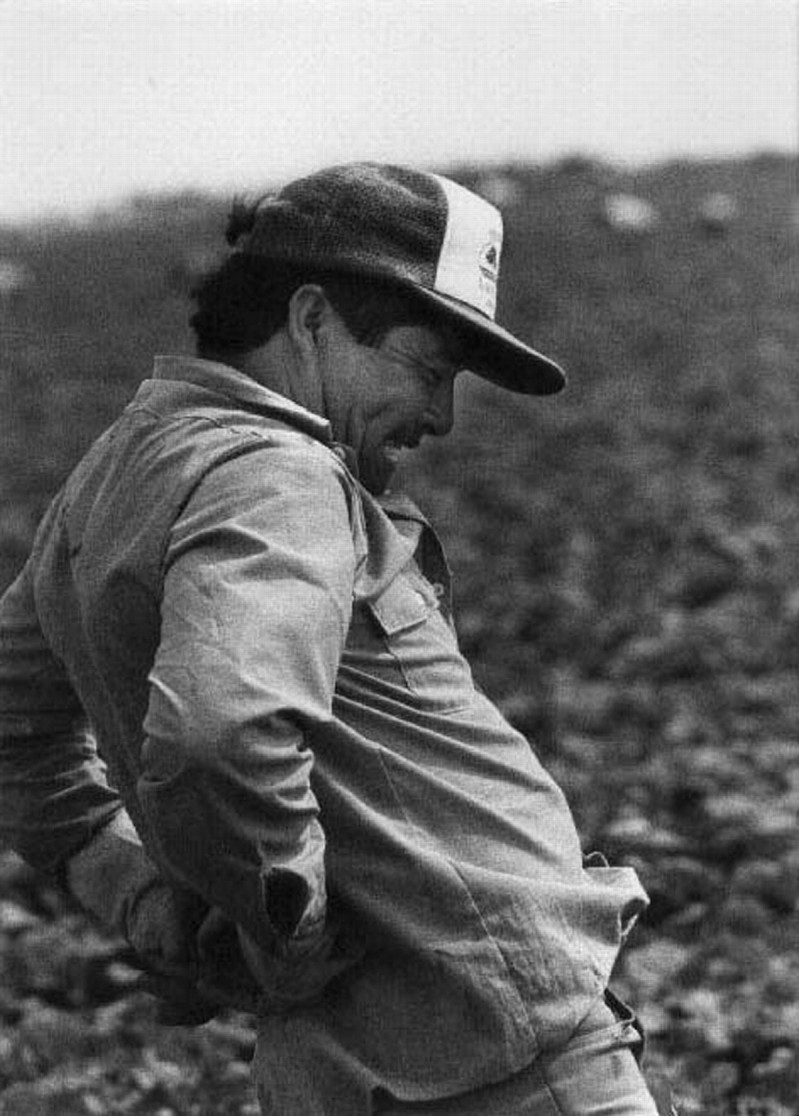

The survey found that farm workers often do not see health care providers even when they are in need of medical attention. More than a third of the state's male agricultural workers have never seen a physician or been to a health clinic. In the latest analysis from the Institute, more than 41% of workers reported some form of musculoskeletal pain lasting a week or more during the previous year.2 When asked what kind of treatment was sought, 71% of men and 69% of women reported receiving no treatment, not even over-the-counter medication.

There is an alarmingly high prevalence of obesity among farm workers—81% of male workers and 76% of female workers are either overweight or obese (the latter defined as a body mass index greater than 30).1 These high rates of obesity reflect the high rates found across the entire low-income minority population of the United States.3 About half of all farm workers have 1 or more of the following conditions: obesity, high blood pressure, and hypercholesterolemia, each of which puts them at risk for coronary artery disease and other chronic diseases, particularly diabetes mellitus.1,4 Perhaps the work demands, leading to lack of time to obtain and cook nutritious food, together with poor dietary habits and seasonal unemployment, contribute to these health problems.

Since the recent publication of the Institute's report, further data analysis indicates that these chronic disease risk factors are related to the amount of time spent in the United States.2 For example, the Institute found that rates of hypercholesterolemia and obesity were much higher among documented male farm workers than undocumented male farm workers. One logical explanation might have been a difference in age—in other words, the documented workers might have been older and, therefore, more likely to be obese and have high cholesterol levels. However, only about 2 years' difference in mean ages was found between documented and undocumented workers. When the Institute looked at the length of time since the workers first entered the United States, it found that the documented subjects had spent just over 19 years in the United States, in contrast to the 7.4 years reported on average by undocumented men, a difference that was statistically significant.

Although it is premature to draw any hard conclusions, the evidence to date suggests that a relationship exists between farm workers' seasonal working patterns, lifestyle, diet, overall risk of chronic disease, and the amount of time that they have been in California. In general, their health appears to decline the longer they are here.

What can be done to address the poor health of farm workers? Their poor health is not inevitable; obesity, hypertension, and high cholesterol levels are all related to preventable “lifestyle” factors. But addressing this problem requires financial investment. Some of this is already coming from California's health care foundations, which are funding projects aimed at reducing health disparities among its population. For example, The California Endowment, the state's largest health care foundation, has formed a task force on farm worker health made up of experts from the public, private, and research communities. The task force was asked to help the foundation prioritize its investments in farm worker health for the next 5 years and to develop a set of prospective initiatives for the California state legislature, which were released in summer 2001. In general, California foundations are playing a vital role in forcing a reluctant government and its citizenry to address its deep-rooted barriers to sustainable development.

It is critical that both our analysis of the problem and our search for solutions are based on a broad view of the entire food system—a food system analysis, rather than a narrow focus on agriculture. A key premise of a food system perspective is that farm worker health is the responsibility of not just employers but of all food consumers. The poor health of farm workers represents a hidden cost of production, and consumers have a role to play in covering these costs. In fact, it would be impossible for most growers to cover the costs of health benefits. Therefore, any comprehensive solution, such as a publicly funded health insurance program for seasonal farm workers, will require a broadening of responsibility to the larger public.

It is also ironic that researchers have uncovered poor health and lack of health insurance in farm workers during a spate of tax cutting in Washington, DC. From the perspective of most health care providers, public health researchers, and health care advocates, the true fiscal surplus of the US government cannot be measured until we have addressed the problems facing the uninsured in our society. Given that the current administration wants to give “the people” back “their money” through tax cuts, the challenge to researchers will be to conclusively demonstrate the long-term cost-effectiveness of universal coverage.

Figure 1.

Back pain is common, but few workers seek help

California Institute for Rural Studies

Competing interest: The California Agricultural Workers Health Survey was conducted by the California Institute for Rural Studies, which received funding from The California Endowment

References

- 1.Villarejo D, Lighthall D, Bade B, et al. Suffering in Silence: A Report on the Health of California's Agricultural Workers. Woodland Hills, CA: The California Endowment; 2000. Available at: www.calendow.org. Accessed July 5, 2001.

- 2.California Program on Access to Care. Access to Care for California's Hired Farm Workers: A Baseline Report. Berkeley: California Policy Research Center, University of California; In press.

- 3.Diabetic and Hypertensive Nephropathy Research Center. Obesity. Available at: www.diabetes-hypertension.com/obesity.htm. Accessed July 5, 2001.

- 4.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, et al. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature 2001;409: 307-312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]