Abstract

Vasectomy damage is a common complication of open nonmesh hernia repair. This study was a retrospective analysis of the characteristics and possible causes of vas deferens injuries in patients exhibiting unilateral or bilateral vasal obstruction caused by open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy. The site of the obstructed vas deferens was intraoperatively confirmed. Data, surgical methods, and patient outcomes were examined. The Anderson–Darling test was applied to test for Gaussian distribution of data. Fisher’s exact test or Mann–Whitney U test and unpaired t-test were used for statistical analyses. The mean age at operation was 7.23 (standard deviation [s.d.]: 2.09) years and the mean obstructive interval was 17.72 (s.d.: 2.73) years. Crossed (n = 1) and inguinal (n = 42) vasovasostomies were performed. The overall patency rate was 85.3% (29/34). Among the 43 enrolled patients (mean age: 24.95 [s.d.: 2.20] years), 73 sides of their inguinal regions were explored. The disconnected end of the vas deferens was found in the internal ring on 54 sides (74.0%), was found in the inguinal canal on 16 sides (21.9%), and was found in the pelvic cavity on 3 sides (4.1%). Location of the vas deferens injury did not significantly differ according to age at the time of hernia surgery (≥12 years or <12 years) or obstructive interval (≥15 years or <15 years). These results underscore that high ligation of the hernial sac warrants extra caution by surgeons during open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy.

Keywords: iatrogenic vas deferens injury, obstructive azoospermia, vasovasostomy

INTRODUCTION

Iatrogenic vas deferens injury most commonly occurs during hernia repair and can cause male infertility.1,2 Globally, more than 20 million hernia surgeries are performed annually, and fertility-related complications are at times inevitable.1 Over the past 30 years, hernia repair methods have markedly changed. For example, open nonmesh surgery has been replaced with the use of polypropylene mesh and laparo-endoscopic repairs. During open nonmesh surgery, cutting, compression, and vascular injury are key contributors to vas deferens atresia. Meanwhile, patch surgery can cause male infertility through compression and adhesion damage. Thus, vas deferens injuries have occurred despite the use of different surgical methods.

Complications associated with the use of mesh reinforcements have been comprehensively investigated in both animals and humans.3 However, it remains difficult to determine at which step during an open nonmesh operation a vas deferens injury is incurred. Due to the low incidence of this injury and an absence of signs and symptoms in children, it is difficult for surgeons to pinpoint critical steps or missteps. Consequently, different opinions regarding possible causes of injury have been expressed. Moreover, ongoing research is important since identification of the cause of a vas deferens injury during open nonmesh hernia repair could effectively protect the reproductive function of a child in a timely and effective manner. Ideally, a review of a large number of clinical cases to explore this issue could provide valuable insight yet remains challenging.

There are numerous patients who underwent open nonmesh hernia repair 20 years ago and are now seeking fertility assistance. These patients exhibit azoospermia or oligospermia as a consequence of an iatrogenic vas deferens injury that was sustained. Treatment of these patients provides an opportunity to explore and identify the aspects of surgery that may have led to this type of injury. In addition, an investigation of whether the occurrence of these reproductive disorders differs between children and adults who have undergone open nonmesh surgery would be valuable.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and clinical characteristics

Patients diagnosed with obstructive azoospermia or oligospermatism that is suspected to have resulted from vasal obstruction during open nonmesh hernia repair were retrospectively analyzed in the Department of Urology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University (Xi’an, China), between January 2013 and December 2020. All of the patients had undergone unilateral or bilateral open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy. Moreover, ipsilateral iatrogenic vas deferens injury was confirmed intraoperatively.

A complete history of the following aspects was obtained for all enrolled patients: time of inguinal herniorrhaphy, genital examination, semen analysis, and ultrasonic examination of the testes. In addition, levels of prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, testosterone, and progesterone were recorded for each patient. The Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital, Xi’an Jiaotong University, approved all procedures (Approval No. 2019-0026). All patients provided informed consent to conduct relevant scientific research on their own data.

Surgical methods

Prior to surgery, patients and their partners are presented with an option to undergo testicular sperm extraction with intracytoplasmic sperm injection or vasal repair. The vasal repair includes vasoepididymostomy (VE) and vasovasostomy (VV) to enable natural conception. However, if no sperm is identified during an intraoperative semen analysis, surgeons may pursue alternative approaches, such as VE, sperm cryopreservation, or testicular sperm extraction.

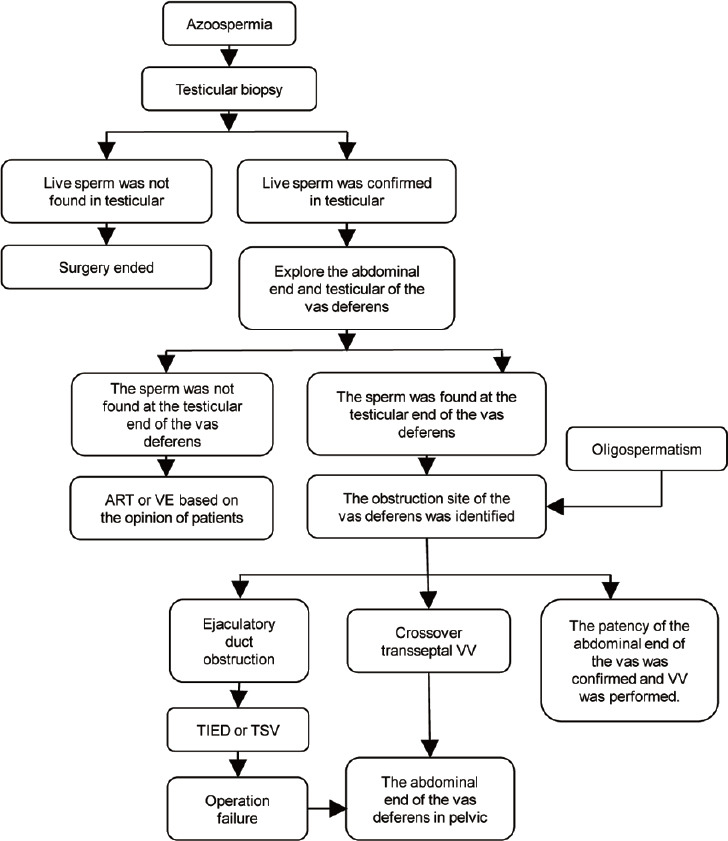

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia (Figure 1). A 16-French Foley catheter was inserted, followed by creation of an incision measuring 3 cm in the scrotal raphe. Testicular sperm were extracted during open biopsy, and the following steps were followed if sperm were observed under high-power magnification.

Figure 1.

Flowchart for the operations performed. ART: assisted reproductive technology; TSV: transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy; VV: vasovasostomy; TIED: transurethral incision of the ejaculatory duct; VE: vasoepididymostomy.

When the vas deferens was identified, 1 cm vas deferens was freed. Methylene blue (Jumpcan Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., Taixing, China) was subsequently injected into the abdominal end of the vas deferens through a 24-gauge angiocatheter to check patency. If obstruction was suspected, a 2-0 prolene was inserted into the vas deferens using an indwelling needle to localize the site of obstruction.

The testicular and abdominal ends of the vas deferens were dissociated when the obstruction site was identified in the inguinal region. Patency of the abdominal end of the vas deferens was tested again using the aforementioned method. Small volumes of saline were injected and aspirated from the testicular end of the vas deferens several times. Once the presence of sperm was confirmed in the saline samples under a microscope (CX43, Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan), a modified 2-layer VV was performed.4,5

If the vas deferens was confirmed with no patency or was indicated by an intraoperative finding of no sperm in the fluid at the testicular end of the vas deferens, subsequent surgical options were determined according to the operation flowchart, as shown in Figure 1. Selection of the final surgical procedure to be performed was determined by the patient and the partner. If spermatic recanalization was selected, VV and a two-needle intussusception VE were performed.5 If the abdominal end of the vas deferens was found in the pelvic cavity, a crossover transseptal VV (CTVV) was performed if patency was confirmed on the opposite side of the vas deferens.6 If the pelvic end of the vas deferens was obstructed while the contralateral testis was absent and the pelvic end of the vas deferens was patent, a CTVV was performed. If patients elected for assisted reproductive technology (ART), a VV was performed and surgery was completed.

If the patient presented with varicocele, hemospermia, or ejaculatory duct obstruction, then microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy,7 transutricular seminal vesiculoscopy,8 or transurethral incision of the ejaculatory duct was performed.

The urethral catheter was removed after 24 h. Two days after surgery, the patient was allowed to begin light activity. Engaging in sports or heavy workload was not allowed for 2 weeks, and sexual activity was to be avoided for 4 weeks postoperatively. For the patients who underwent a VE, they were asked to wear scrotal support for 6 weeks.

Semen samples were collected and assessed 6 months after surgery. Sperm motility grade was determined according to the guidelines of the 4th edition of the World Health Organization.9 For azoospermia, patency was considered to have been achieved if sperm concentration >10 000 ml−1.

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 18.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). The Anderson–Darling test was applied to test for Gaussian distribution of data. The unpaired t-test or Mann–Whitney U test was applied to nonnormally distributed data. Fisher’s exact test was applied for analyses of different operation age groups and obstructive interval (OI) groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All of the patients had a medical history of unilateral or bilateral open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy. Azoospermia or oligospermatism was confirmed based on two consecutive semen samples collected 6 weeks apart, with the ejaculate having normal volume and pH. Urinalysis was performed to rule out retrograde ejaculation. Some patients with a history of unilateral open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy, who concurrently had varicocele, hemospermia, ejaculatory duct obstruction (EDO), or cryptorchidism, also underwent surgical exploration.

Testicular volume was measured by ultrasound in 38 of 43 patients, including 64 cases of testes on the iatrogenic vas deferens injury side (mean volume: 15.07 [s.d.: 1.28] ml, range: 12.69–17.83 ml) and 11 cases of testes on the uninjured side (mean volume: 15.98 [s.d.: 0.98] ml, range: 14.34–18.08 ml). There was no statistical difference between the two groups (P = 0.07), but the volume of testis of iatrogenic vas deferens injury side was smaller than that on the uninjured side.

All patients were examined for sex hormone before operation, including estrogen (mean: 34.40 pg ml−1, range: 25.90–53.04 pg ml−1), total testosterone (mean: 563.40 ng dl−1, range: 261.00–831.00 ng dl−1), follicle-stimulating hormone (mean: 4.67 mIU ml−1, range: 2.72–8.40 mIU ml−1), luteinizing hormone (mean: 5.87 mIU ml−1, range: 3.15–10.30 mIU ml−1), progesterone (mean: 0.31 ng ml−1, range: 0.09–1.17 ng ml−1), prolactin (mean: 17.29 ng ml−1, range: 6.49–27.10 ng ml−1), and free testosterone (mean: 26.02 pg ml−1, range: 7.64–37.35 pg ml−1). The sex hormones of all patients are within the normal ranges (Supplementary Table 1).

Supplementary Table 1.

The volume of testis and sex hormone of patients

| Patient number | Age (year) | Left testis | Right testis | Estradiol (pg ml−1) | FSH (mIU ml−1) | Prolactin (ng ml−1) | Progesterone (ng ml−1) | Testosterone (ng dl−1) | LH (mIU ml−1) | FT (pg ml−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Volume (ml) | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Height (mm) | Volume (ml) | |||||||||

| 1 | 18 | 37 | 27 | 21 | 14.90 | 41 | 23 | 22 | 14.73 | 37.4 | 3.82 | 9.67 | 0.226 | 687 | 8.42 | 37.35 |

| 2 | 22 | 38 | 25 | 20 | 13.49 | 39 | 25 | 21 | 14.54 | 28.5 | 5.46 | 13.9 | 0.136 | 469 | 10.3 | 19.98 |

| 3 | 21 | 42 | 26 | 23 | 17.83 | 38 | 27 | 23 | 16.75 | 26.9 | 3.34 | 15.72 | 0.162 | 615 | 9.16 | 30.14 |

| 4 | 27 | One side testis absent | 39 | 26 | 20 | 14.40 | 27.4 | 3.63 | 19.68 | 0.452 | 543 | 6.72 | 36.47 | |||

| 5a | 23 | 40 | 26 | 22 | 16.24 | 38 | 25 | 23 | 15.51 | 30.5 | 3.43 | 16.67 | 0.126 | 437 | 10.16 | 27.46 |

| 6 | 23 | 38 | 25 | 23 | 15.51 | 37 | 24 | 22 | 13.87 | 25.9 | 4.44 | 9.65 | 0.146 | 567 | 5.38 | 24.52 |

| 7 | 23 | 39 | 25 | 21 | 14.54 | 41 | 26 | 21 | 15.89 | 26.8 | 5.61 | 14 | 0.217 | 637 | 5.45 | 23.42 |

| 8 | 27 | 37 | 24 | 23 | 14.50 | 39 | 27 | 23 | 17.20 | 27.9 | 2.88 | 16.4 | 0.088 | 261 | 6.5 | 19.9 |

| 9 | 22 | 40 | 26 | 22 | 16.24 | 40 | 24 | 22 | 15.00 | 33 | 3.42 | 6.49 | 0.214 | 327 | 6.21 | 19.93 |

| 10 | 25 | 38 | 24 | 23 | 14.89 | 43 | 25 | 21 | 16.03 | 31.3 | 4.1 | 13.4 | 0.13 | 412 | 5.8 | 21.1 |

| 11 | 23 | 37 | 27 | 22 | 15.60 | 37 | 23 | 21 | 12.69 | 30.2 | 4.56 | 17.92 | 0.158 | 536 | 4.51 | 23.65 |

| 12 | 25 | 37 | 28 | 24 | 17.65 | 40 | 26 | 24 | 17.72 | 26.8 | 5.21 | 19.79 | 0.381 | 547 | 5.36 | 24.31 |

| 13 | 25 | 39 | 25 | 21 | 14.54 | 41 | 24 | 22 | 15.37 | 31.2 | 4.48 | 27.1 | 0.326 | 568 | 6.35 | 22.72 |

| 14 | 23 | 38 | 26 | 22 | 15.43 | 38 | 26 | 21 | 14.73 | 38.6 | 6.35 | 22.4 | 0.485 | 721 | 3.71 | 28.77 |

| 15a | 26 | 42 | 26 | 19 | 14.73 | 41 | 27 | 23 | 18.08 | 35.5 | 3.47 | 20.3 | 0.225 | 768 | 6.52 | 31.43 |

| 16 | 22 | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | 29.8 | 5.23 | 16.72 | 0.372 | 342 | 5.78 | 26.5 |

| 17 | 25 | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | 34.5 | 3.53 | 15.34 | 0.237 | 831 | 3.71 | 24.18 |

| 18 | 28 | 40 | 25 | 21 | 14.91 | 39 | 26 | 21 | 15.12 | 41.3 | 4.42 | 16.4 | 0.347 | 532 | 5.35 | 31.28 |

| 19 | 27 | 38 | 23 | 21 | 13.03 | 38 | 27 | 21 | 15.30 | 31.51 | 4.24 | 15.35 | 0.156 | 770.3 | 5.82 | 29.54 |

| 20 | 25 | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | 42.38 | 3.82 | 19.72 | 0.62 | 614.2 | 4.28 | 26.74 |

| 21 | 24 | 40 | 26 | 20 | 14.77 | 39 | 25 | 22 | 15.23 | 28.5 | 4.43 | 24 | 0.328 | 714 | 3.56 | 27.71 |

| 22 | 26 | 38 | 27 | 23 | 16.75 | 40 | 26 | 23 | 16.98 | 41.6 | 4.47 | 22 | 0.415 | 684 | 7.42 | 32.07 |

| 23 | 22 | 36 | 25 | 22 | 14.06 | 39 | 25 | 22 | 15.23 | 34.2 | 3.62 | 16.82 | 0.346 | 381 | 3.15 | 7.64 |

| 24a | 24 | 36 | 25 | 21 | 13.42 | 38 | 26 | 24 | 16.84 | 32.1 | 4.15 | 14.2 | 0.383 | 521 | 4.33 | 21.5 |

| 25a | 25 | 41.5 | 25 | 21 | 15.47 | 38 | 24 | 21 | 13.60 | 37.6 | 4.56 | 15.4 | 0.26 | 477 | 4.64 | 22.4 |

| 26a | 24 | 39 | 26 | 21 | 15.12 | 36 | 24 | 23 | 14.11 | 35.4 | 7.12 | 16.5 | 0.354 | 358 | 6.49 | 21.73 |

| 27 | 23 | 38 | 23 | 22 | 13.65 | 38 | 25 | 21 | 14.16 | 28.9 | 4.43 | 13 | 0.451 | 557 | 5.64 | 24.16 |

| 28a | 33 | 41 | 26 | 21 | 15.89 | 37 | 27 | 21 | 14.90 | 53.04 | 3.27 | 20.3 | 0.614 | 752 | 8.19 | 33.72 |

| 29 | 18 | 39 | 26 | 22 | 15.84 | 39 | 25 | 22 | 15.23 | 43.4 | 3.45 | 19.28 | 0.186 | 814 | 4.86 | 31.28 |

| 30 | 26 | 41 | 24 | 20 | 13.97 | 39 | 26 | 19 | 13.68 | 36.2 | 6.31 | 14.3 | 0.158 | 524 | 5.27 | 23.49 |

| 31a | 22 | 40 | 25 | 22 | 15.62 | 38 | 25 | 20 | 13.49 | 37.9 | 5.59 | 16.4 | 0.436 | 692 | 5.76 | 29.67 |

| 32 | 32 | 37 | 24 | 22 | 13.87 | 40 | 27 | 23 | 17.64 | 29.6 | 7.44 | 15.3 | 0.167 | 483 | 6.13 | 24.3 |

| 33 | 25 | 36 | 26 | 21 | 13.96 | 36 | 25 | 21 | 13.42 | 31.6 | 3.51 | 26.8 | 0.241 | 587 | 5.33 | 27.65 |

| 34 | 26 | 37.5 | 25.1 | 22.1 | 14.77 | 36.1 | 25.4 | 24.5 | 15.95 | 36.3 | 6.21 | 16.5 | 0.232 | 543 | 4.58 | 30.14 |

| 35 | 27 | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | 41.2 | 4.8 | 15.7 | 0.28 | 765 | 5.51 | 27.64 |

| 36 | 28 | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | Miss | 38.1 | 8.4 | 18.3 | 1.17 | 447 | 7.28 | 31.2 |

| 37 | 28 | 41 | 25 | 23 | 16.74 | 42 | 25 | 21 | 15.66 | 46 | 2.72 | 15.1 | 0.312 | 563 | 3.42 | 27.58 |

| 38 | 25 | 39 | 27 | 20 | 14.95 | 38 | 26 | 20 | 14.03 | 36.7 | 5.43 | 21.3 | 0.224 | 673 | 7.69 | 31.32 |

| 39a | 26 | 37 | 26 | 21 | 14.34 | 36 | 27 | 21 | 14.49 | 35.6 | 4.86 | 17.5 | 0.25 | 554 | 5.88 | 24.55 |

| 4a | 29 | 38 | 26 | 22 | 15.43 | 39 | 28 | 23 | 17.83 | 38.5 | 4.56 | 14.57 | 0.263 | 532 | 4.76 | 21.32 |

| 41a | 26 | 39 | 24 | 23 | 15.28 | 38 | 27 | 20 | 14.57 | 34.7 | 4.63 | 15.61 | 0.224 | 582 | 5.21 | 23.16 |

| 42 | 28 | 42 | 25 | 23 | 17.15 | 39 | 24 | 21 | 13.96 | 32.78 | 5.26 | 23.31 | 0.615 | 456.5 | 5.67 | 25.73 |

| 43a | 26 | 37 | 24 | 22 | 13.87 | 40 | 25 | 22 | 15.62 | 31.8 | 6.14 | 24.5 | 0.321 | 382 | 6.18 | 19.42 |

aThe testicle on the one side without vas deferens injury. FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; LH: luteinizing hormone; FT: free testosterone

A total of 47 patients underwent surgery for azoospermia or oligospermia between 2013 and 2020, but four patients were lost to follow-up. Thus, among the 43 enrolled patients (mean age: 24.95 years, range: 18–33 years), 73 sides of the inguinal region were explored. The mean age at the time of inguinal herniorrhaphy was 7.23 (s.d.: 2.09) years, and the mean OI was 17.72 (s.d.: 2.73) years.

Nine patients were diagnosed with oligospermia and 34 with azoospermia. The patients underwent modified VV (or at least unilateral VV), and none of the patients, in whom sperm was not found in the fluid at the proximal end of the vas deferens, chose to undergo a VE. The overall patency rate was 85.3% (29/34), and the wives of three patients reported natural pregnancy at 6 months postoperatively. Conversely, sperm was not detected in five patients 6 months after the operation. In two patients (four sides), although sperm were intraoperatively detected in the fluid of the testicular end of the vas deferens and anastomosis of the vas deferens was observed, there were also no sperm detected 6 months postoperatively.

Thirteen patients who had recently undergone unilateral open nonmesh inguinal herniorrhaphy were diagnosed with azoospermia or oligospermatism. One patient underwent a unilateral VV for the other absent testis, whereas a second patient underwent a unilateral VV and orchidectomy for an intra-abdominal cryptorchidism. In another patient (two sides), VV was performed on one side, and a crossover transseptal VV was performed on the other side for the abdominal end of the vas deferens that was in the pelvic cavity. Three patients ultimately chose ART. Among these, two patients (four sides) declined a VE since sperm were not intraoperatively detected in the fluid of the testicular end of the vas deferens, and one patient had an abdominal vasal stump located in the pelvic cavity. The details regarding the remaining patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients with a history of inguinal herniorrhaphy

| Patient number | Age (year) | The age at the time of hernia repair (year) | Obstruction site | Both or single side | Suffer disease of the other side | Diagnosis | The sperm concentration before operation (×106 ml-1) | Operation approach | The sperm concentration at 6 months postoperation (×106 ml-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 3 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 19.7 |

| 2 | 22 | 4 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 11.5 |

| 3 | 21 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 16.6 |

| 4 | 27 | 4 | Inner | Single | Testis absent | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.7 |

| 5 | 23 | 3 | Middle | Single | NA | Oligospermatism | 3 | VV | 21.2 |

| 6 | 23 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 13.3 |

| 7 | 23 | 4 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.6 |

| 8 | 27 | 6 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 0 |

| 9 | 22 | 4 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 15.6 |

| 10 | 25 | 5 | Middle | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VVa | 0 |

| 11 | 23 | 4 | Middle/inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 21.3 |

| 12 | 25 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 17.2 |

| 13 | 25 | 4 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 18.3 |

| 14 | 23 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 19.3 |

| 15 | 26 | 6 | Inner | Single | EDO | Azoospermia | 0 | VV + TIED | 22.6 |

| 16 | 22 | 5 | Middle/inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.3 |

| 17 | 25 | 6 | Pelvic | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | Failure to find distal vasal stump | 0 |

| 18 | 28 | 5 | Inner/middle | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 12.1 |

| 19 | 27 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 16.5 |

| 20 | 25 | 6 | Middle | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 0 |

| 21 | 24 | 7 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 12.1 |

| 22 | 26 | 6 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 17.9 |

| 23 | 22 | 6 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 16.6 |

| 24 | 24 | 6 | Inner | Single | Cryptorchidism | Azoospermia | 0 | VV + orchidectomy | 24.8 |

| 25 | 25 | 8 | Inner | Single | Varicocele | Oligospermatism | 7.2 | VV + MSV | 20.1 |

| 26 | 24 | 8 | Inner | Single | Varicocele | Oligospermatism | 4.8 | VV + MSV | 16.6 |

| 27 | 23 | 9 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 21.1 |

| 28 | 33 | 5 | Middle | Single | Varicocele | Oligospermatism | 6.9 | VV + MSV | 15.9 |

| 29 | 18 | 3 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 13.7 |

| 30 | 26 | 8 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.3 |

| 31 | 22 | 4 | Middle | Single | Hematospermia | Oligospermatism | 7.7 | VV + TSV | 17.2 |

| 32 | 32 | 8 | Inner/middle | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.6 |

| 33 | 25 | 5 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 19.1 |

| 34 | 26 | 12 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VVa | 0 |

| 35 | 27 | 15 | Pelvic/middle | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV + CTVV | 16.3 |

| 36 | 28 | 13 | Middle | Single | Hematospermia | Oligospermatism | 10.3 | VV + TSV | 18.1 |

| 37 | 28 | 15 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 14.9 |

| 38 | 25 | 13 | Middle/inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 17.3 |

| 39 | 26 | 12 | Inner | Single | Varicocele | Oligospermatism | 5.8 | VV + MSV | 18.9 |

| 40 | 29 | 14 | Middle | Single | EDO | Azoospermia | 0 | VV + TIED | 19.3 |

| 41 | 26 | 15 | Inner | Single | NA | Oligospermatism | 7.3 | VV | 17.8 |

| 42 | 28 | 13 | Inner | Both | NA | Azoospermia | 0 | VV | 12.3 |

| 43 | 26 | 12 | Middle | Single | Varicocele | Oligospermatism | 3.8 | VV + MSV | 22.0 |

aNo sperm was found in the fluid of the proximal vas. VE: vasoepididymostomy; TIED: transurethral incision of the ejaculatory duct; TSV: transurethral seminal vesiculoscopy; VV: vasovasostomy; EDO: ejaculatory duct obstruction; CTVV: crossover transseptal VV; NA: not applicable; MSV: microsurgical subinguinal varicocelectomy

Among the 73 sides of the 43 patients, 54 sides (74.0%) of the disconnected ends of the vas deferens were found in the internal ring, 16 sides (21.9%) were found in the inguinal canal, and three sides (4.1%) were found in the pelvic cavity. Location of the vas deferens injury did not significantly differ according to patient age at the time of surgery (≥12 years or <12 years) or according to OI (≥15 years or <15 years), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics for different groups

| Characteristic | Age at the time of hernia surgery | Obstructive interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| <12 years | ≥12 years | <15 years | ≥15 years | |

| Age (year), mean±s.d. | 24.36±2.25 | 26.90±1.10 | 25.87±0.94 | 24.74±2.39 |

| Age at the time of hernia surgery (year), mean±s.d. | 5.36±1.23 | 13.40±1.08 | 12.88±1.63 | 5.94±1.82 |

| Obstructive interval (year), mean±s.d. | 19.00±2.12 | 13.50±1.20 | 13.00±1.00 | 18.80±2.19 |

| Total sperm concentration at 6 months postoperation (×106 ml-1), mean±s.d. | 18.30±2.40 | 18.80±2.22 | 18.90±2.66 | 18.40±2.29 |

| Obstruction site (n)a | ||||

| Inner | 45 | 9 | 9 | 45 |

| Middle | 11 | 5 | 3 | 13 |

| Pelvic cavity | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Patency or obstruction (n)b | ||||

| Patency | 29 | 9 | 7 | 31 |

| Obstruction | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

Fisher’s exact test. aBetween the two age groups at the time of hernia repair; P=0.14; between the two obstructive interval groups, P=0.27. bBetween the two age groups at the time of hernia repair, P>0.99; between the two obstructive interval groups, P>0.99. s.d.: standard deviation

No Clavien–Dindo II–V complications were observed in all patients. Hematuria occurred in two patients with EDO and two patients with hematospermia after operation and disappeared after 3 days; six patients had hidden pain in one or two sides of the epididymis, which relieved spontaneously in a week.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of seminal tract obstruction caused by inguinal herniorrhaphy ranges from 0.3% to 7.2%.10 This rate increases to 26.7% with unilateral vas deferens obstruction.11 Taken together, these results suggest that injuries to the vas deferens typically go unnoticed and are underreported in infants and children. In general, injuries are identified when fertility problems present much later in life.1 In addition, subfertility does not always manifest if a unilateral obstruction is present. In the present study, 9 of 43 patients manifested subfertility because they had undergone unilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy during childhood and also experienced other concurrent diseases such as varicocele (n = 5), hematospermia (n = 2), or cryptorchidism (n = 2). In these patients, oligospermia eventually developed.

All 43 patients in our cohort were confirmed to have iatrogenic von deferens injuries. There are many reasons for vas deferens obstruction caused by herniorrhaphy. The likelihood of vasal obstruction after inguinal herniorrhaphy may be influenced by the surgical approach used (laparoscopic vs open), by pediatric versus adult herniorrhaphy, and by the use of nonmesh versus other materials to bolster repair.3 The prosthetic material used in hernia surgery may also induce a chronic inflammatory reaction, or the mesh may be placed in proximity to the vas deferens and cause obstruction.3,12 During open nonmesh hernia repair surgery, a vas deferens injury can be caused by cutting, compression, or both. However, it is also possible that a ureteral injury can occur due to the vas deferens being too thin or carelessness in a doctor’s technique. It remains a topic of debate which step in the operation is likely to cause a vas deferens injury.8,13,14

Herein, we included 43 patients (73 sides) with identified vas deferens obstruction who underwent open surgery for hernia repair without the use of a polypropylene mesh. In 74.0% (54/73 sides) of these sides, the vas deferens injury occurred in the internal inguinal ring and the abdominal end of the vas deferens was found in the pelvic cavity on only three sides. These observations suggest that adhesion, cutting, and other such maneuvers occurred near the internal inguinal ring.

Previously, Matsuda et al.11 reported that most cases involving an obstructed vas (57.1%) had the obstruction detected at the internal inguinal ring or even more distally in the pelvic cavity. We speculate that high ligation of the hernia sac close to the inner ring of the inguinal canal may be the predominant cause of damage to the vas deferens during open nonmesh hernia repair. High ligation of the hernia sac is the most important step in hernia repair and is performed closer to the end of the surgery, which results in a high success rate, low morbidity, limited postoperative pain, and good cosmesis.15 Moreover, this step always involves unclear exposure of some tissues and anatomical structures. Thus, it is possible that excessive traction of the spermatic cord may result in a ligature cut and compression of the vas deferens.

There still remains much controversy regarding possible causes of damage to the vas deferens during open nonmesh hernia repair. Some studies suggest that the vas deferens of children is damaged during surgery because they are not fully matured and the tube walls are thin. Consequently, they would be easily damaged during surgery. Other authors have proposed that damage to the vas deferens occurs in the middle inguinal canal, and the abdominal end of the vas deferens regresses to the inner ring of the inguinal canal or pelvis as the child develops.5,8 To further investigate possible causes of vas deferens damage, 43 patients in the present study were divided according to age at the time of hernia surgery (≥12 years or <12 years) and according to OI (≥15 years or <15 years). No significant between-group differences were observed in regard to either of these two parameters according to the different obstruction sites involved (e.g., internal inguinal ring, middle of the inguinal canal, and pelvic cavity). Taken together, these results suggest that vas deferens injuries in most cases are not due to thin tube walls or damage in the middle inguinal region. Rather, a vas deferens injury is more likely to be caused by a ligature cut and compression at the internal inguinal ring during open nonpatch hernia repair.

Considering that some patients in our group were rather young and that pregnancy is affected by many factors,16 we re-analyzed the semen of our patients 6 months after surgery to investigate the patency of the vas deferens. The high overall patency rate observed (85.3%, 29/34) can be explained by the quality of the sperm being sampled from the testicular end of the vas deferens. The sperm samples were at least grade 2 according to the Silber scale before a micro VV was performed. This is consistent with previous reports that semen grade is an important indicator of the patency of the vas deferens.17,18 Correspondingly, semen grade has a 4.1-fold17 and 14-fold19 higher odds ratio of postoperative patency when the intravasal fluid contains a large proportion of spermatozoa than when only sperm fragments and no sperm are present. In addition, a modified 2-layer VV also has precise mucosal approximation with watertight anastomosis and no difference in patency compared to 2-layer anastomoses.5 Furthermore, the modified 2-layer VV is more time- and cost-effective than the 2-layer technique.20

OI has always been a point of concern when discussing the patency rate of VV. Moreover, numerous studies have reported conflicting results in this regard. One perspective is that patency rates decrease or gradually decline as the interval after vasectomy increases. For example, Magheli et al.21 reported that 52% of patients with an OI >15 years required at least a unilateral VE. Conversely, Boorjian et al.22 reported that patency rates (88%–91%) did not significantly change after more than 15 years postvasectomy. Furthermore, neither patient’s age at the time of hernia repair, nor OI, has exhibited a statistically significant effect on the rate of patency.22 Based on the present results, we propose that the most important factor affecting patency is that the quality of sperm obtained from the testicular end of the vas deferens is at least grade 2, which is consistent with previous reports.16,18

CONCLUSIONS

To date, the number of open nonmesh hernia repairs performed is gradually decreasing, concomitant with advances in new technologies. However, vasectomy damage remains a common complication of open nonmesh hernia repair and often occurs at the site of high ligation of the hernial sac. Due to the small sample size of the present study, our conclusions remain to be further verified with larger and more diverse sample sizes. However, they do suggest that this surgical step needs to be performed with utmost care.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JZ contributed to protocol and project development and manuscript writing and editing. XQZ and HCL contributed to data collection and writing of the manuscript. TC contributed to project development and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

All authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Asian Journal of Andrology website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bouchot O, Branchereau J, Perrouin-Verbe MA. Influence of inguinal hernia repair on male fertility. J Visc Surg. 2018;155:S37–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulster ML, Cohn MR, Najari BB, Goldstein M. Microsurgically assisted inguinal hernia repair and simultaneous male fertility procedures:rationale, technique and outcomes. J Urol. 2017;198:1168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clancy C, Jordan P, Ridgway PF. Polypropylene mesh and systemic side effects in inguinal hernia repair:current evidence. Ir J Med Sci. 2019;188:1349–56. doi: 10.1007/s11845-019-02008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andino JJ, Gonzalez DC, Dupree JM, Marks S, Ramasamy R. Challenges in completing a successful vasectomy reversal. Andrologia. 2021;53:e14066. doi: 10.1111/and.14066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namekawa T, Imamoto T, Kato M, Komiya A, Ichikawa T. Vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy:review of the procedures, outcomes, and predictors of patency and pregnancy over the last decade. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17:343–55. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korkes F, Neves OC. Crossover transseptal vasovasostomy:alternative for very selected cases of iatrogenic injury to vas deferens. Int Braz J Urol. 2019;45:392–5. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2018.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiraishi K, Oka S, Matsuyama H. Surgical comparison of subinguinal and high inguinal microsurgical varicocelectomy for adolescent varicocele. Int J Urol. 2016;23:338–42. doi: 10.1111/iju.13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen XF, Wang HX, Liu YD, Sun K, Zhou LX, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic strategies of obstructive azoospermia in patients treated by bilateral inguinal hernia repair in childhood. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:745–8. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.131710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination of Human Semen and Sperm-Cervical Mucus Interaction. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin D, Lipshultz LI, Goldstein M, Barmé GA, Fuchs EF, et al. Herniorrhaphy with polypropylene mesh causing inguinal vasal obstruction:a preventable cause of obstructive azoospermia. Ann Surg. 2005;241:553–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000157318.13975.2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuda T, Horii Y, Yoshida O. Unilateral obstruction of the vas deferens caused by childhood inguinal herniorrhaphy in male infertility patients. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:609–13. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schouten N, van Dalen T, Smakman N, Elias SG, van de Water C, et al. Male infertility after endoscopic Totally Extraperitoneal (Tep) hernia repair (Main):rationale and design of a prospective observational cohort study. BMC Surg. 2012;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer WC, Meacham RB. Vasal reconstruction above the internal inguinal ring:what are the options? J Androl. 2006;27:481–2. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaeer OK, Shaeer KZ. Pelviscrotal vasovasostomy:refining and troubleshooting. J Urol. 2005;174:1935–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176738.55343.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer LS, Palmer JS. Management of abnormalities of the external genitalia in boys. In: Wein AJ, editor. Campbell-Walsh Urology:4-Volume Set. 11th ed. Philadelphiap: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 3384–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker K, Sabanegh E., Jr Obstructive azoospermia:reconstructive techniques and results. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2013;68:61–73. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2013(Sup01)07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scovell JM, Mata DA, Ramasamy R, Herrel LA, Hsiao W, et al. Association between the presence of sperm in the vasal fluid during vasectomy reversal and postoperative patency:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology. 2015;85:809–13. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiwari DP, Razik A, Das CJ, Kumar R. Prospective analysis of factors predicting feasibility &success of longitudinal intussusception vasoepididymostomy in men with idiopathic obstructive azoospermia. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149:51–6. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1192_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramasamy R, Mata DA, Jain L, Perkins AR, Marks SH, et al. Microscopic visualization of intravasal spermatozoa is positively associated with patency after bilateral microsurgical vasovasostomy. Andrology. 2015;3:532–5. doi: 10.1111/andr.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nyame YA, Babbar P, Almassi N, Polackwich AS, Sabanegh E. Comparative cost-effectiveness analysis of modified 1-layer versus formal 2-layer vasovasostomy technique. J Urol. 2016;195:434–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magheli A, Rais-Bahrami S, Kempkensteffen C, Weiske WH, Miller K, et al. Impact of obstructive interval and sperm granuloma on patency and pregnancy after vasectomy reversal. Int J Androl. 2010;33:730–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boorjian S, Lipkin M, Goldstein M. The impact of obstructive interval and sperm granuloma on outcome of vasectomy reversal. J Urol. 2004;171:304–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000098652.35575.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]