Abstract

The mass incarceration of Black people in the United States is gaining attention as a public health crisis with extreme mental health implications. Although it is well-documented that historical efforts to oppress and control Black people in the United States helped shape definitions of mental illness and crime, many psychologists are unaware of the ways our field has contributed to the conception and perpetuation of anti-Blackness and, consequently, the mass incarceration of Black people. In this paper, we draw from existing theory and empirical evidence to demonstrate historical and contemporary examples of psychology’s oppression of Black people through research and clinical practices and consider how this history directly contradicts the American Psychological Association (APA)’s ethics code. First, we outline how anti-Blackness informed the history of psychological diagnoses and research. Next, we discuss how contemporary systems of forensic practice and police involvement in mental health crisis response maintain historical harm. Specific recommendations highlight strategies for interrupting the criminalization of Blackness and offer example steps psychologists can take to redefine psychology’s relationship with justice. We conclude by calling on psychologists to recognize our unique power and responsibility to interrupt the criminalization and pathologizing of Blackness as researchers and mental health providers.

Introduction

“Psychiatry is an auxiliary of the police” – Frantz Fanon

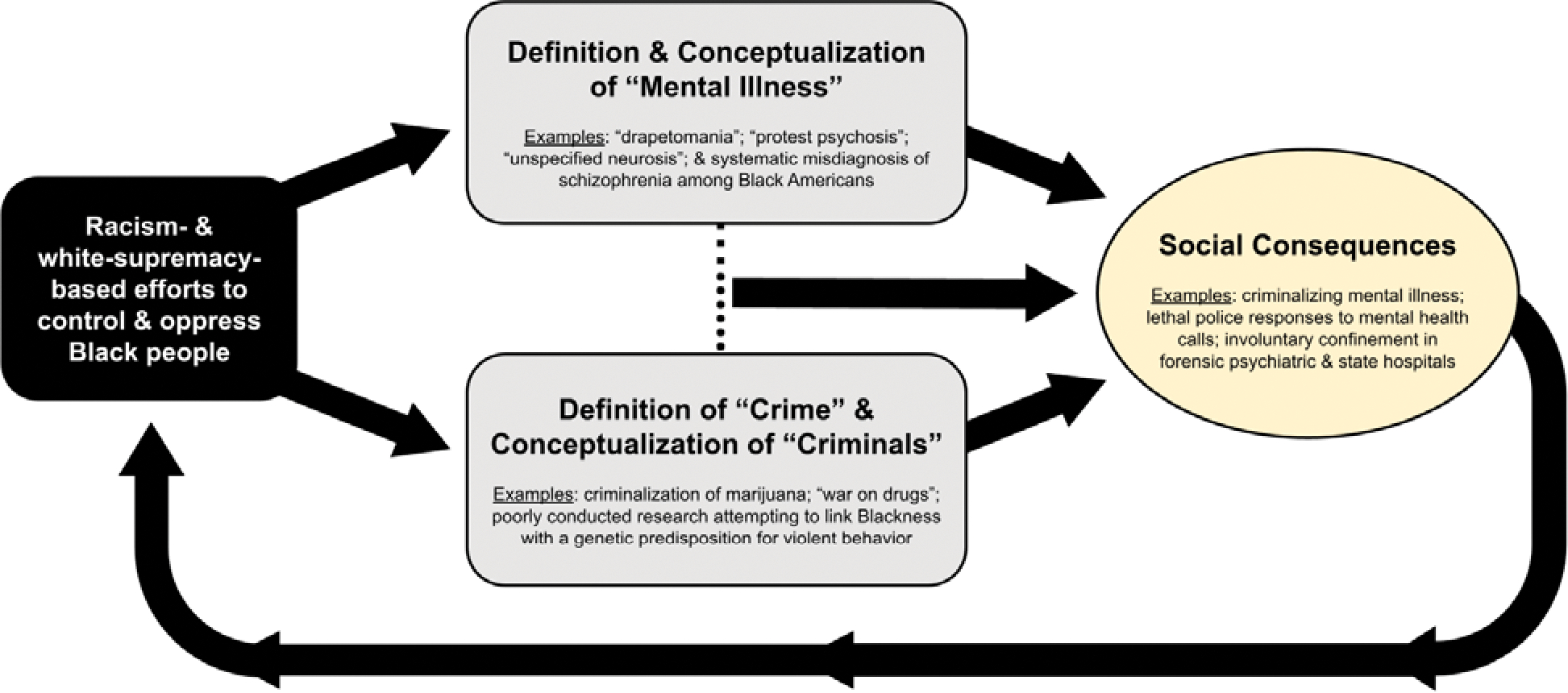

Mass incarceration is increasingly gaining attention as a public health crisis (Bowleg, 2020). Despite representing only 5% of the world’s population, the United States is responsible for 22% of the incarcerated population globally (Walmsely, 2016). Further, racial disparities in sentencing are stark and have resulted in the disproportionate incarceration of Black people (Alexander, 2011). The overall rate of incarceration and the racial inequity in incarceration stem in part from the United States’ longstanding punitive stance towards Black populations (Alexander, 2011). Indeed, efforts to oppress and control Black people in the United States played an important role in shaping definitions of and institutional responses to mental illness and crime (Figure 1). Our field’s complicity with this oppression can be observed in the conceptual roots of psychiatry and psychology, from Carl Jung’s beliefs that African peoples struggled to produce coherent ideas and were thus capable of rendering White people more primitive through extended contact (Collins, 2009; Vaughan, 2019), to G. Stanley Hall’s (1905) conception that criminality was firmly rooted within the mind of African people. Unfortunately, many psychologists are unaware of the ways in which our field has contributed to the conception and perpetuation of anti-Blackness and, consequently, the contemporary mass incarceration of Black people.

Fig. 1. The conception and reproduction of anti-Blackness.

Racism-based efforts to oppress and control Black people have shaped and continue to shape the definitions of and institutional responses to “mental illness” and “crime.” These definitions and responses give rise to many social consequences that feed back into racist stereotypes and perpetuate anti-Black oppression. Given the long-standing intersection between mental health and mass incarceration, psychologists have a responsibility to use their unique roles as mental-health researchers and providers to redefine and reform this system.

In 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. addressed the American Psychological Association (APA) and called for mental health professionals to care for the Black communities impacted by cultural, structural, and interpersonal racism (King, 1968). However, the mental health field continued to neglect Black communities in subsequent decades, adopting and reinforcing stereotypical and deficit-based perspectives concerning Black people (Cross, 2003; White, 1970). As noted by Hilliard (1978), any clinical psychologist who seeks to serve Black communities needs to reconcile the desire to serve with the field’s complicity in and perpetuation of racism. To this end, there is an urgent need for researchers and mental health providers to have an honest reckoning with psychology’s role in the perpetuation of anti-Blackness and the oppression of Black people.

The primary aims of this paper are: (1) to provide a critical analysis of psychology’s historical and contemporary contributions to anti-Blackness in research and clinical practice, and (2) to critique the intersection between the criminal legal system and contemporary research and clinical practice in psychology. To achieve these aims, we incorporate theory and empirical research from several fields, including Black mad studies, Black/African-centered psychology, liberation psychology, disability studies, and contemporary forensic psychology. We begin by outlining how anti-Blackness has informed the history of psychological diagnoses, institution building, and research. We provide historical and contemporary examples of psychological and epistemic oppression of Black people in research and clinical practice, underscoring how this history contradicts the APA’s code of ethics. We then offer an analysis of how contemporary forensic practices maintain this historical harm as well as the role of police involvement in mental health crisis responses. We highlight specific case studies to exemplify the complex and challenging positions that clinical and forensic psychologists face while working in criminal legal settings. We conclude by underscoring our responsibility as researchers and mental health providers to interrupt the criminalization and pathologizing of Blackness.

A History of Anti-Blackness in Psychiatry and Psychology

To unpack the history of anti-Blackness in the fields of mental health, Fanon’s (2020) understanding of psychiatry (under which psychology was subsumed) as an extension of policing is key. Fanon intimated that in the Western world, including Europe and the Americas, the field of psychiatry historically concerned itself with surveilling and controlling the minds and bodies of people deemed “other.” Mbembe (2019) posited that, in the broadest sense, interventions against non-Western peoples were driven by two core assumptions: (1) non-Western populations should be like “us,” and (2) non-Western peoples are not capable of being like “us.” Black people in particular bore the brunt of this surveillance and control within the United States where the political economy relied heavily on the enslavement and dehumanization of African peoples (King, 2019). The perceived inferiority of Black people guided the development of psychology and its use on these communities, leading to the use of psychology in the acculturation of people to Western capitalism and White supremacy (Danziger, 1990; Myers, 1987). For example, Boykin and Toms (1985) articulated how early education in the United States sought to socialize Black children into norms and values consistent with Western cultural hegemony. As previously noted, these conceptions were given veneers of validity through psychological theory. Consequently, the cultures and heritage of Black youth were seen as contributing to their deficits (Akbar, 1978). Further, any inability to acculturate was imagined to be evidence of innate inferiority (Akbar, 1978). From this context, we can begin to understand how and why psychology historically pathologized and incarcerated generations of racially minoritized people.

Anti-Blackness and the Conception of Psychological Diagnoses

As it pertains to pathology, psychology upheld racist beliefs that supported the United States’s cultural, political, and economic structure. Indeed, the concepts of sanity and Blackness in the United States are so historically intertwined that Pickens (2019) argued “... within the United States’s cultural zeitgeist, there is no Blackness without madness, nor madness without Blackness” (p. 27). For instance, in 1840, the United States Census Report inaccurately reported that free Black people were ten times more likely to be “insane” compared to those who were enslaved. These data were intentionally fabricated to argue that the psyche of Black people was incapable of handling freedom and to justify their continued enslavement (Suite et al., 2007). To further this issue, in 1851, Dr. Samuel Cartwright published a paper in which he claimed to have identified a new mental health disorder specific to Black people known as “drapetomania.” Cartwright described drapetomania as a form of mania that manifested as an uncontrollable desire to run away from the White master (Suite et al., 2007). Such racism continued to guide the development and application of psychological diagnoses for nearly two centuries. It is within this context that American psychologists, inspired by the works of Galton, Piaget, among others, contributed to an attempted genocide through eugenics. As noted by Yakushko (2019),

A review of the official publications of American eugenic societies reveals that 31 presidents of the American Psychological Association between 1892 (Stanley G. Hall’s presidency) and 1947 (Carl Roger’s presidency) were publicly listed as leaders of various eugenic organizations. (p. 7)

These leaders in the field of psychology contributed to shifting United States state laws to broadly adopt eugenicist policies (e.g., forced sterilization policies; Kaelber, 2012). Such policies in turn buoyed broad conceptions of Black people, among other minoritized groups, as naturally inferior and harmful to the advancement of Western civilization. Indeed, Black people were disproportionately diagnosed with ill-fitting diagnoses based on tests intentionally designed to venerate White biological and cultural superiority, diagnoses that directly led to the institutional hospitalization and sterilization of Black people (Yakushko, 2019). These diagnoses continued to be wielded politically towards the end of the 20th century. Specifically, diagnoses have been consistently used to pathologize Black protest movements and Black political leaders (Metzl, 2010). For example, Bronberg & Simons (1968) conceptualized “protest psychosis” to describe Black people they were observing in their in-patient hospital who were active members of radical Black protest movements.

Racism also shifted how diagnoses were conceived, which continues to impact Black people today. For example, schizophrenia’s criteria were gradually revised to more efficiently capture how Black people were presenting in hospitals in the mid-to-late 60s (Metzel, 2010). The diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia began to reference the types of “aggression” and “paranoia” that were believed to be characteristic of Black patients. Such shifts in the cultural application and conception of psychotic disorders still disproportionately impact Black people. For example, even when Black and White people present with similar symptoms, Black people are significantly more likely than White people to be diagnosed with psychotic disorders whereas White people are more likely to be diagnosed with mood disorders (Schwartz & Blankenship, 2014; Schwartz et al., 2019). These racial biases in diagnosis are especially alarming because psychotic symptoms, even when below clinical threshold, are associated with substantially heightened rates of incarceration and involuntary hospitalization (Narita et al., 2022; Swanson et al., 2009). Furthermore, experimental evidence has demonstrated that specifically for Black people, the presence (vs. absence) of symptoms associated with psychotic disorders (e.g., talking to self loudly, ‘erratic behaviors’) is associated with increased public support for the use of police force (Kahn et al., 2017). In contrast, for White people, the perceived presence of these same symptoms serves as a protective factor and is associated with decreased public support for the use of police violence (Kahn et al., 2017). The impact of these racial biases is not limited to adults with perceived psychotic disorders. For example, Black youth historically have been denied the category of adolescence, have had their mental health needs ignored, and have been disproportionately diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder and other conduct disorders, which increases their risk for incarceration starting from childhood and adolescence (Atkins-Loria et al., 2015; Galán et al., 2022; Goff et al., 2014; Henning, 2013). Thus the influence of racism on the conception and application of psychological disorders has reinforced the disproportionate institutionalization and incarceration of Black people.

Institutionalization and Incarceration of Blackness

Involuntary and indefinite confinement has historically been used as a method of cultural control within the United States (Teuten, 2014). While these methods are not solely rooted in the practice of psychology or psychiatry, as noted, these fields have often given such practices a veneer of scientific validity. Indeed, the history of psychiatric institutionalization and community control by mental health professionals led Wright (1974) to conclude that the discipline had historically been leveraged for war against Black populations. Based on anti-Black construction of mental health disorders, myriad hospitals were built to enforce social control. For instance, the Central Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane, the first state psychiatric hospital for Black people, forcibly institutionalized thousands of Black people in Virginia beginning in 1870 (Peterson, 2021). Hospital archives reveal that Black people were taken from their communities and enslaved on the belief that freedom produced mania and forced labor was an adequate treatment (Peterson, 2021). Throughout the 20th century, these practices were common. Based on the eugenic laws supported and championed by psychologists, Black people, and Black women specifically, endured disproportionate and forced sterilizations and confinement (Kaelber, 2012). For instance, The Human Betterment Foundation oversaw the forced sterilization of thousands of Black patients in psychiatric institutions based on perceptions of mental defect (Kaelber, 2012). Late in the 20th century, these practices were still common. The Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Michigan justified the life-long confinement of Black men until it was closed in 1977 (Metzl, 2010). Specifically, the institution enacted control through disproportionate application of culturally stigmatized diagnoses, such as the aforementioned “protest psychosis” which pathologized the very act of Black political resistance. Beyond disrupting the freedom and humanity of generations of Black people, the impact of these institutions still contributes to medical mistrust among these communities. Further, human rights abuses within psychiatric institutions have received global attention (Whaley, 2003; World Health Organization, 2021). Also contributing to mistrust has been the historic role of psychologists in coordination with state social services disproportionately disrupting and breaking apart Black families. However, a full overview of the impacts of the foster care system is beyond the scope of this review (see Roberts, 2022).

The field of Black/African-Centered Psychology was conceptualized and developed to address the rampant harm and exploitation of Black people in the United States and throughout the world (X[Clark] et al., 1975; White, 1970; Wright, 1975). While acknowledging the diversity of cultural, ethnic, and historic experiences among African-descendent peoples, Nobles (1972) noted several cultural similarities that tied distinct groups together through migration and cultural exchange. These cultural similarities, what Myers (1987) termed the deep structure of culture, became the theoretical foundation for Black/African-Centered Psychology. As such, according to Grills (2006), Black/African-Centered Psychology “represents an Africentric framework…a genre of thought and praxis rooted in the cultural image and interest of people of African ancestry.” (p. 172). Further, scholars like Amos Wilson, Kobi Kambon, and Daudi Azibo formally integrated Black/African-centered psychology and Liberation Psychology by theorizing on the connections between political systems and collective well-being for Black people (Jamison, 2013). As noted by Jamison (2013), the actual integration of psychology, spirit, radical politics, and liberation to counter cultural hegemony did not occur within academia. Rather, it can be seen in lives of various Black and African revolutionaries (e.g. Dutty Boukman, Cecile Fatiman, Nat Turner, Apongo, Nzingha Mbande, etc.), as well as the everyday men and women who survived and protected their loved ones (Haartman, 2019; Maat, 2010). It should be noted that while there has been substantial empirical work based on theories of African-Centered/Black psychology, approaches based in Afrofuturism and Afropessimism also have substantial theoretical grounding. These approaches provide alternatives for understanding the scope of the problem and imagining possible solutions (e.g., Bowleg et al., 2021; Pickens, 2019).

It is important to emphasize that historicizing the harms against Black people that we have described above does not distance contemporary people from these effects. Indeed White nationalists in the modern day continue to leverage the legacy of these works (Hemmer, 2017). Many communities continue to maintain a mistrust of the field based on legitimate experiences of harm (see Utsey, 2021). At present, the carceral history of psychology remains relevant to research, practice, and policy solutions generated from the discipline of psychology. In fact, the APA is still recovering from a recent scandal in which the organization supported the indefinite confinement and torture of international prisoners in the United States (Gomez et al., 2016).

Within that context, the American Psychological Association (APA) recently released a review of psychology’s historical contributions to racism in the United States (APA, 2021). Yet, while the report expresses APA’s commitment to combating racism and attempts to highlight the progression of psychology towards a more just field, such a movement cannot be authentic without acknowledging the organization’s, and our profession’s, current intersections with the criminal legal system (APA, 2021). Further, as noted by Wilson (1993), the myth of recounting history as ‘progress’ risks ignoring how people have both “integrated” and “disintegrated” throughout time (p. 8). That is to say, it risks discounting increases in societal harm that run counter to frames of progress. As such, the Association of Black Psychologists, Inc ([ABPsi], 2021) issued a denial of the apology based on a recognition of the continued harm perpetuated by the field at large on Black people.

Ultimately, the persistent conflation of dangerousness, madness, and Blackness has continued to result in the deaths of Black people who need care and understanding, from the beating of Billy Ray Johnson to the killing of Elijah McClain (Glasrud, 2014; Hutson et al., 2022). Such moral failures reveal the need for psychology to deliberately address and re-imagine its relationship to justice if the field is to guide the nation towards practices and policies that center mental health and well-being. This begins by examining how psychological research has contributed to a century of anti-Black criminalization.

Black Oppression and Exclusion via Psychological Research

Throughout its history, research on psychological science has (1) used active and passive discriminatory practices to advance harmful narratives about Black people and (2) systematically neglected to center the experiences of race and related psychological phenomena among Black people. These practices have resulted in the degradation of Black communities and gatekeeping of potential benefits to these communities from advances in knowledge and interventions gleaned from psychological science. Epistemic oppression is persistent and systematic exclusion that hinders advances in knowledge in a given area. We reflect on two primary examples below to highlight the damaging effects of discriminatory research practices and pervasive epistemic oppression in psychological science on the well-being and livelihood of Black communities (Held, 2020). We discuss how these harmful research practices have been leveraged to justify the policing and mass incarceration of Black people. Further, we emphasize how the field of psychological science continues to remain complacent regarding these issues.

What About Integrity (Principle C)? Psychology’s History of Pathologizing and Othering Black People via Research Malpractice

Principle C: Integrity, of the APA’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2016), states that “psychologists seek to promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness in the science, teaching, and practice of psychology.” To embody this principle of integrity, we must first reflect on the sordid past and present of psychology’s and psychiatry’s joint roles in the oppression of Black people. Throughout the history of psychological and psychiatric research, many scientists actively attempted to link Blackness with a biological predisposition toward violence and criminality. Methodological and statistical malpractice were the most common tools used to achieve this goal. Examples of such malpractice include investigations seeking to explicitly link criminal “traits” with Blackness and publications reporting spurious interpretations of individual-level factors as the central cause of differences between groups to further dehumanize already “othered” groups (Held, 2020). A more extensive review of similar examples of methodological and statistical malpractice follows.

We would like to believe that these types of targeted studies are a historical artifact for our field (i.e., studies attempting to explicitly and “biologically” link Blackness with character deficits, problem behaviors, and criminal traits). However, it is important to recognize that such studies are still conducted and continue to permeate our modern literature and collective subconscious, including appearing in psychology textbooks (Dupree & Boykin, 2021). Take, for example, a study published in 2020 in the journal Intelligence, which reported findings linking lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores with increases in behavioral problems among a sample of mostly minoritized racial and ethnic youth from families earning incomes below the federal poverty line (Kavish et al., 2020; for a more extensive critical analysis on this topic, see Giangrande & Turkheimer, 2022). Another study published in 2020 in the journal Sexual Assault utilized a dichotomous race/ethnicity variable (White vs. “non-White”) and reported that non-White adolescents were more likely to be early-onset sexual offenders compared with White adolescents (Rosa et al., 2020). Clearly these practices are an ongoing issue that must be addressed head on. Furthermore, in lieu of actively conducting research promoting anti-Black sentiments, many psychological scientists remain complacent, continuing to perpetuate unjust practices that harm Black communities through spurious interpretations of data and (un)witting dissemination of existing harmful literature (e.g., reporting race differences in outcomes without contextualizing these health outcomes in relation to structural racism). Whether intentional or not, these practices perpetuate deterministic conceptualizations of Black people as inevitable predators or hopeless lost causes and function to justify the over-policing and incarceration of Black communities (Cross, 2003; Potts, 1997).

Harmful Research on Biologically-Based Determinants of Criminality

One of the most egregious examples of active research malpractice is demonstrated by attempts to link the biology of young Black people, especially males, with aggression, violence, impulsivity, callousness, and other trait-like characteristics, relegating them to criminal status. Scholars such as Harriet Washington have chronicled this history of degradation, offering detailed accounts of how psychological and psychiatric research have blatantly and vociferously perpetrated these harms (2006). For example, she described a study conducted by psychologists at Columbia University between 1992 and 1997 that was focused on elucidating genetic and family risk factors for antisocial behavior (Wasserman et al., 1996; Pine et al., 1997). Researchers in this study intentionally restricted their sampling to Black and Hispanic younger brothers of justice-involved youth living in under-resourced neighborhoods. In fact, Washington’s (2006) investigative work revealed that though the sample reported was 44% Black and 56% Hispanic, the Hispanic boys were in fact Black Dominicans, suggesting that Black youth were targeted specifically (Wasserman et al., 1996; Pine et al., 1997). In addition to assuming a genetic basis of delinquent behavior, the investigators further presumed that “bad parenting” among low-income, Black parents contributed to producing delinquent children (Washington, 2006). Notably, “bad parenting” in this case was used as a catch-all term that encapsulated a range of factors that are more systemic than characterological (i.e., “parental psychopathology” and “adverse rearing environments”). Moreover, these investigators used coercive methods to recruit young Black boys into their study. For example, although it is illegal to share legal records of minors, the Department of Probation cooperated with the researchers and identified justice-involved older brothers, enabling the researchers to contact their families and recruit their younger brothers. Some parents, citing fear of retaliation that might negatively affect their justice-involved sons, felt pressure to consent to participation. These researchers demonstrated clear biases and a lack of respect for Black families as they wielded knowledge of the fears Black parents held that their children would be victimized by the justice system. Thus, this knowledge was used to coerce participation in research studies that were degrading to the families and actively harmful to their children.

In addition to these predatory recruitment strategies and biased hypotheses, the methodology employed by the investigators demonstrated a clear disregard for the safety of young Black people in the pursuit of evidence confirming biased preconceptions linking Blackness with delinquency. Specifically, the investigators administered a serotonergic drug called fenfluramine, which floods synapses with serotonin and inhibits reuptake. This increased synaptic serotonin leads to rises in prolactin levels, which are used as a proxy measure for serotonergic activity. Fenfluramine was selected as prior studies had shown that retrospective reports of chronic aggression in childhood predicted a blunted prolactin response to fenfluramine, leading the researchers to hypothesize that the association between aggression and blunted serotonergic activity may arise early in life (Pine et al., 1997). Importantly, however, fenfluramine had never before been used with young children, and had known side effects including anxiety, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and irritability (Washington, 2006). Further, other studies had shown associations between fenfluramine usage and heart-valve damage and pulmonary hypertensions, and these reports and Food and Drug Administration warnings about the use of fenfluramine were already circulating during the time these studies took place (see for example Connol1y et al., 1997). Nevertheless, the researchers felt justified in leveraging this dangerous methodology in their study with Black children. Importantly, restricting the sample to Black youth made it impossible for readership to conclude anything other than spurious claims about Black youth and violent traits (Washington, 2006; Wasserman et al., 1996; Pine et al., 1997).

In addition to her critique on the suite of fenfluramine studies, Washington (2006) also describes prior studies that have advanced false narratives regarding the biological determinism [i.e., the belief that most human characteristics are determined objectively by hereditary factors and are thus uninfluenced by social and environmental factors (for additional examples, see: Belkhir & Duyme, 1998; Guthrie, 2004)] of violence in Black people. One such study examined associations between low-intelligence and heightened aggression, violence, and propensity for criminality with the presence of the XYY genetic anomaly (Borgaonkar, 1978; Borgaonkar, & Shah, 1974). This study was conducted among a mostly Black (~85%) sample of adolescent boys, most of whom were wards of the state (Borgaonkar, 1978; Borgaonkar, & Shah, 1974). This anomaly was assumed to reflect a type of “supermale-ness” due to the extra Y chromosome. Importantly, none of the many studies conducted provided any evidence to support that the XYY genetic anomaly was more prevalent in Black men. This willingness to waste time and resources in pursuit of uncovering these associations further illustrates how these deeply held stereotypes propel malicious and misguided studies.

The aforementioned studies demonstrate a clear bias towards investigating genetic and biologically-based determinants of violence among minoritized youth specifically. From the mission advanced by funding agencies (i.e., researching biological bases for psychopathy and delinquency), to the study design, recruitment tactics, hypotheses, procedures, and writing, there is a clear path for bias and vested interests to impact the research process at every turn. Further, when these atrocities have been brought before courts, justice for these families and communities has proven elusive (Washington, 2006). This lack of justice signals to Black families and communities that they are neither valued nor protected if they participate in psychological and psychiatric research. This willful disregard for basic respect and wellbeing, lack of accountability, and disproportionate benefit to White populations have in concert created a deep sense of distrust among Black communities regarding the safety and likelihood of any potential benefits that may arise from participation in psychological and psychiatric research (George et al., 2013; Scharff et al., 2010). And are such fears not warranted? Such practices are by definition at odds with the ethical standard stating that our duty as psychologists is to seek to promote accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness in the science, teaching, and practice of psychology. Stated plainly, we must do better.

Case Examples of Recurrent Passive Acceptance of Continued Degradation of Black Communities

Attempts to locate violence in the biology of Black people have thwarted efforts to address the system drivers of social inequities (i.e., disparities in education, employment, or access to effective and holistic healthcare among these communities). Indeed, such sentiments of biological determinism relating to psychological outcomes continue to be reified in modern-day popular scholarship in the fields of behavioral psychology and genetics (e.g., Plomin, 2018). Beyond the personal toll on Black individuals, yet another devastating result of this pattern is that resources and favorable policies are diverted away from Black communities, perpetuating and reinforcing cycles of poverty, racism, and ultimately systemic oppression (Gee & Ford, 2011). In addition to the history of psychologists and psychiatrists actively pursuing racist research agendas, psychological science has and continues to passively permit practices that similarly harm Black individuals and communities. For example, the field has largely failed to challenge persistent and common racist stereotypes that dehumanize and stigmatize Black people. Some examples of the most enduring among these stereotypes include attempts to illustrate Black people as (a) less intelligent and (b) more likely to use and deal drugs than non-Black people.

Problematic Research on Intelligence, Delinquency, and Blackness.

As a case example, take the highly-cited study (nearly 900 citations) by Lynam and colleagues (1993), in which they examined the relation between IQ and delinquency. In their discussion, they make several harmful claims as they attempt to justify why the inverse correlation they found between IQ and delinquency was stronger among Black boys than White boys, including:

Blacks are disproportionately represented in depressed, unstable, and socially isolated inner-city communities (Wilson, 1987) … we suggest that school failure plays a more important role for Black boys because school provides a source of social control that is lacking in the neighborhood. The boy who finds school so frustrating that he rejects it and what it represents is removing himself from its control and influence. Neighborhood delinquents and pressures are free to rush in and fill the void. (p. 195)

In this example, the authors reinforce the use of racial disparities in IQ tests as a meaningful determinant of negative psychosocial outcomes and, in particular, the racist conceptualization linking lower IQ among Black youth with delinquency. Additionally, they blame Black families and communities for failing to provide adequate degrees of “social control” over their Black youth. They also condemn Black boys themselves, who are depicted as personally responsible for school failure and for becoming so frustrated that they stop identifying with school values of conformity. Together, this rhetoric blames delinquency on Black families and neighborhoods as well as individual Black boys without discussing social context (Cross, 2003).

Despite segregation being ruled unconstitutional in 1954 and strides made toward equitable access to educational opportunities among Black communities, biases persist that negatively impact the experiences of Black youth in school settings (Noguera, 2003). Among many issues, pervasive beliefs that Black youth are not interested in nor capable of learning engender lower expectations of Black youth that in turn negatively influence educational outcomes (Gershenson et al., 2016; Leath et al., 2019; Neblett et al., 2006). Further, Black youth experience disproportionately harsh school punishments compared to their White peers, who exhibit similar or worse behaviors (Government Accountability Office, [GAO], 2018; Gopalan & Nelson, 2019; Okonofua & Eberhardt, 2015; Riddle & Sinclair, 2019). Black youth also face inequitable distribution of school resources, such as selection for talented and gifted programs, to foster their educational advancement (Grissom & Redding, 2016). Finally, a lack of racial representation among educators and cultural representation within curricula have been linked to less academic motivation and persistence for Black children (Gordon et al., 2009; Grissom et al, 2009; Hilliard, 1991; Lindsay & Hart, 2017). Considering this context opens a range of alternative explanations for why some Black boys may “find school so frustrating,” and ultimately “reject it,” if it is even fair to use that language in the first place. Still, given that this article has been cited nearly 900 times (although we hope many of these citations are from articles refuting the authors’ harmful claims), it is safe to say that many psychological scientists have used these ideas to inform their own research with Black youth. This highlights the insidiousness of how racist stereotypes spread and ultimately undermine the integrity of our science and the wellbeing of Black communities. In addition, these stereotypes manifest beyond our respective academic silos and our field at large to permeate popular culture. In this way, these sweeping generalizations and rushed judgments engender the very stereotypes and thinking that make it so easy for cops to pull their triggers a little more willingly (Plant & Peruche, 2005; Pleskac et al., 2018; Swencionis & Goff, 2017) and for judges to hand down harsher sentences more readily for Black offenders (United States Sentencing Commission, 2017).

These ideas permeate beyond public opinion and perception into public policies that have continued to undermine the wellbeing of Black communities for generations, unchallenged and uncorrected by psychologists for far too long. For example, early liberal-identifying social scientists, such as Daniel Moynihan, espoused ideals using terminology such as “tangle of pathology” to refer to the economic inequality and psychological impacts of racism experienced by Black Americans (Hinton, 2017). Drawing on social science research and psychological theory, Moynihan argued that delinquency, crime, unemployment, and poverty resulted from unstable Black families, further engendering a sense of pathology specific to Black people (Hinton, 2017). Though Moynihan appropriately attempted to impart upon then President Johnson the importance of recognizing the role of the federal government in helping Black communities by examining lingering institutional racism, President Johnson ignored these pleas. Unchecked, President Johnson selectively embraced Moynihan’s statements about the instability of Black families to justify the development of programs that merged the War on Crime with the War on Poverty. Specifically, he introduced new surveillance programs that eventually gave rise to the current carceral state in America (Hinton, 2017).

Harmful Research on Drug Use Among Black People.

As another example of psychological science failing to debunk – or even actively perpetuating – racist stereotypes with harmful downstream consequences, many studies have sought to link Blackness with elevated rates of drug dealing and drug use. However, empirical evidence indicates that Black people are no more – and in many cases less – likely to deal or use drugs compared with non-Hispanic White people, a trend that has been consistent since the late 1970s (Bachman et al., 1991; McCabe et al., 2007; Welty et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2011). For example, among previously detained youth assessed over a period of 12 years following release, substance use disorders were most prevalent among non-Hispanic White people and least prevalent among Black people at each of the five follow-up time points (Welty et al., 2016). This was true for all substances, including alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, hallucinogens, PCP, opiates, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, and other unspecified drugs (Welty et al., 2016). However, the “War on Drugs” has effectively stigmatized Black people who use substances as “dangerous others” who are either unable to be or unworthy of being helped. Simultaneously, it has garnered public sympathy around the disproportionately elevated rates of heroin and prescription opioid use among predominantly White populations (Netherland & Hansen, 2016; Schuler et al., 2021). These narratives demonizing and targeting Black people who use substances have continuously reinforced racist policies increasing policing in Black communities and, until recently, have heightened sentencing recommendations for even first-time, minor drug charges (Cooper, 2015; Lynch, 2012).

Indeed, Black people continue to be disproportionately arrested for cannabis possession compared to White people, including in states that have decriminalized or legalized cannabis (Edwards & Madubuonwu, 2020). This is yet another example of oppression of Black people reinforced by the perpetuation of characterological fallacies that attempt to synonymize drug use with immorality, antisocial traits, delinquency, and, ultimately, Blackness. Importantly, these policies and practices have resulted in the imprisonment of generations of Black people at rates far higher than their White counterparts for similar behaviors (Camplain et al., 2020; Cooper, 2015; Lynch, 2012), and the associated stigma and stereotypes persist today. We want to be clear that we are not calling for increasing criminal sentencing for White people who use drugs. Rather, we advocate for decriminalization of drug use in service of destigmatizing substance use behavior, decoupling associations between drug use and criminality, and importantly, abolishing the racist criminal legal system practices that have targeted and harmed Black people for generations (for further reading on this topic, see Earp et al., 2021).

Psychological and psychiatric researchers who understand the highly complex underpinnings of substance use have, despite some efforts (e.g., Hart 2017; Heilig et al., 2021), failed to effectively oppose these mischaracterizations and the racist policies they engender. Moreover, our historically misguided and unethically reported research and the interpretations provided by researchers are often (mis)used to directly guide racist media messages and policies. Even when psychologists ourselves are not conducting such harmful studies and analyses, we often fail to acknowledge how these prevailing messages have downstream effects on the public and public policy. This is likely in part because most of us have yet to realize our role in perpetuating these narratives and the responsibility we bear to provide accurate information about drug use and addiction to counter these egregious mischaracterizations. Doing the research and publishing our findings is simply not enough; it is imperative that psychological science move toward an advocacy model to intentionally center antiracism in our work to effectively curtail these avoidable negative impacts on Black communities.

What About Justice (Principle D)? How Psychological Science Has Failed to Accurately Examine and Represent Black Experiences

Principle D: Justice, of the APA’s Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (2016), states that “psychologists recognize that fairness and justice entitle all persons access to and benefit from the contributions of psychology and to equal quality in the processes, procedures, and services being conducted by psychologists.” However, psychological science has and continues to fail to represent Black people in research, both as participants and investigators, resulting in an “omission of concepts embedded in the lived experience of othered peoples” (Held, 2020; p. 350). Systemic exclusion of experiences of race and related psychological phenomena among Black people leads to a dearth of possible benefits of psychological science for these populations, and further perpetuates a willful ignorance about the experiences of these groups.

Exclusion of Black People from Intervention & Assessment Research

Not only have many stigmatizing studies systematically recruited only low-income Black families to bolster deterministic agendas as described above, but others have systematically excluded these populations when there may be some benefit to their participation. For example, throughout the history of intervention research in psychology and psychiatry, most randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of treatments for psychopathology, including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and ADHD, have included very few if any Black people in their samples. Data pooled from a 15-year period between 1986 and 2001 demonstrate that only 6.7% of the approximately 10,000 participants in these various RCTs were members of minoritized racial and ethnic groups (Miranda et al., 2003; Office of the Surgeon General et al., 2001). In fact, ethnicity was reported in less than half of those RCTs, and not one clinical trial reported the efficacy of the developed treatments among minoritized racial and ethnic groups (Miranda et al., 2003; Office of the Surgeon General et al., 2001). These norms in racial selection in intervention research perpetuate health disparities because treatments are selectively validated among homogenous groups of White and wealthy individuals, and thus may not be generalizable to Black people and lower SES populations.

These exclusionary practices have also severely biased the development of standardized tests that are widely used in educational and assessment settings, which was brought to light by Robert Williams in his work demonstrating the misuse of IQ testing for Black children (Williams, 1971). In fact, due to the aforementioned misalignment and misuse of IQ testing on Black children, the Bay Area branch of ABPsi successfully demonstrated this harm in Larry P. v. Riles (1971). A group representing Black students who had been placed in special education classes due to performances on IQ tests sued the San Francisco Unified School District for racial bias and discrimination. The judge decided in favor of the students and placed a moratorium on IQ testing of Black students based on evidence of clear cultural bias.

Exclusion of Research on Experiences of Black People from Publication

In addition to lack of representation of Black participants in intervention and assessment research, the exclusion of research by Black scientists from high-impact academic journals actively silences these perspectives and perpetuates the White-washing of studies on experiences of race. Research on mass incarceration, police brutality, the criminal legal system, and related topics is often segregated to “specialty” journals, when these topics should be of import to broader audiences. Indeed, issues that disproportionately affect Black people are rarely featured in high-impact journals that reach wide, often majority White audiences.

Roberts and colleagues (2020) effectively illustrate the magnitude of this issue by demonstrating the extent of exclusion of psychological studies examining racial and ethnic experiences from top journals in psychology, and especially those with the broadest readership. Among approximately 26,000 publications sampled from the 1970s to 2010s in cognitive, developmental, and social psychology, Roberts and colleagues (2020) identified several striking trends. First, only about 5% of publications highlighted race at all (i.e., mentioned racial categories, racial identity, racial segregation, racial stereotyping, racial inequality), indicating that within the subfields of psychological science, questions centering racial and ethnic experiences and their relation to psychological constructs are systematically excluded. They additionally found that a startlingly small minority (5%) of editors in chief were people of color, and 93% of manuscripts on race were edited by White editors. More shocking is their finding that greater proportions of White editorial board members predicted fewer publications that highlighted race being accepted (Roberts et al., 2020). Finally, among publications highlighting race, approximately half of participants in those studies were White, indicating that published papers on race and racialized experiences rarely focus solely on the experiences of minoritized racial and ethnic groups. It is also worth noting that White participants were significantly more common in papers authored by White researchers, whereas participants of color were more represented in publications authored by researchers of color. When we consider that there are many fewer researchers of color than White researchers, this statistic becomes even more unsettling. Together, all of the aforementioned harmful exclusions – of the study, inclusion, and support of Black people via psychological research – both actively and passively serve to continuously other Black people. Specifically, neglecting to publish scientifically-rigorous, inclusive research thoughtfully-conducted by scientists with diverse perspectives is just as damaging to Black communities as publishing spurious and misleading studies that encourage dangerous interpretations. The unfortunate reality is that much of our field’s research is not meeting the standard of permitting all persons access to and benefit from the contributions of psychology and to equal quality in the processes, procedures, and services being conducted by psychologists. Undoubtedly, we must change psychological research practices and the structures that uphold them to ensure our field does not continue to perpetuate these harms (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations for Addressing Psychology’s History of Research Misconduct and Harm Toward Black Communities

| Initiative | Action |

|---|---|

| At The Level of Individuals and Academic Departments | |

| Educate budding psychologists about the historical maltreatment of Black and other minoritized racial and ethnic communities in the context of psychology research malpractice | • Update syllabi, readings, and course materials to foster a more thorough reflection on psychology’s maltreatment of Black and other communities of color beyond the classic examples (i.e., Milgram and Tuskegee experiments) • Use effective teaching strategies (Burnes and Singh, 2010): (1) Use of course readings to increase knowledge, (2) Including self-examination and self-reflection exercises in courses, and (3) Bridging this knowledge and awareness-based learning with experiential learning activities • Facilitate critical examination of ongoing research and the ways in which specific framing, studies, or programs of research may be interpreted or used for harm by oppressive systems (see for example, Buchanan et al., 2021) |

| Diversify course readings and materials to introduce a more holistic and equitable narrative | • Elicit faculty commitment to dedicate consistent attention and effort towards engaging in equitable teaching practices that center diversity, equity, and inclusion • Develop and provide resources for faculty to diversify existing syllabi with more articles authored by Black scientists and scientists of color, articles specifically within the field of Black Psychology, and articles that specifically examine experiences of race and related psychological phenomena (see for example: https://heystacks.org/doc/425/bipoc-authored-psychology-papers) • Engage faculty in yearly updates to their syllabi and create a departmental syllabi review committee to assess the appropriateness and diversity of included readings, materials, etc. • To foster engagement in syllabus diversification, evaluate faculty on their use of diversified syllabi and incorporate these ratings into course evaluations that students can access prior to course selection to inform whether a course is right for them |

| At The Level of Journals & Funding Agencies | |

| Create structures to promote equitable research practices among journals and funding agencies | • Make clear the journal’s or funding agency’s standards for publication and grant funding (i.e., “minimum standards of equity”), such as prioritizing studies that center: experiences of race, meaningfully diverse samples, or samples with a majority of people from minoritized racial backgrounds, and those proposed by Black scientists and other scientists of color • Explicitly instruct reviewers to consider the racial/ethnic makeup of the sample, particularly if the content of an article or grant involves the study of race and related psychological phenomena • Encourage reviewers to consider the backgrounds of the writers of the article or grant in relation to the content • Establish “equity committees” among journals and funding agencies to ensure that publication of studies examining diverse populations and authored by diverse scientists are being accepted at more equitable rates • Incorporate more diverse members on journal and funding agency boards and selection committees to ensure a more equitable selection process and distribution of resources, which will promote more equitable (and interesting) science • Create pools of funding to be allocated specifically for studies that will center experiences of race and related psychological phenomena and/or the creation and validation of community-based interventions to address the lingering impacts of systemic oppression |

| Acknowledge past harms and prevent continued misinformation | • Acknowledge past harms and actively prevent their recurrence by recalling past articles when the harm or potential for harm is particularly pronounced • Retroactively append articles with a disclaimer signaling recognition of the potential harm and guidance to ensure that data and claims be interpreted in the proper context |

Given the broad recognition of mass incarceration’s disparate and deleterious effects on Black communities, many researchers and advocates have pushed for reform that centers mental health care (e.g., Kaba, 2021; O’Brien et al., 2021, Klukoff et al., 2021). These reforms may ideally be situated into areas of clinical practice in which psychologists work with legally-involved individuals, given that their key roles as researchers and clinicians can impact the wellness of individuals and communities with whom they work. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the ways in which mental healthcare and the criminal legal system intersect in complicated ways for psychologists. We turn now to describing the issues ingrained in these overlapping systems.

Harmful Interplay Between Mental Health Care and the Criminal Legal System

Psychologists’ clinical skill and content area expertise afford power in influencing the lives of others at multiple levels – from conducting clinical research to providing therapeutic services to advocating for policy change. The ethical principles set forth by the American Psychological Association implore psychologists to use this power to “safeguard the welfare and rights of those with whom they interact professionally and other affected persons” (APA, 2016). Yet, the predominant system of mental health crisis response in the United States is grounded in a criminal legal system that disproportionately harms individuals with mental illness, Black people, and those who have both identities (e.g., Edwards et al 2019). Mental health crisis response is undeniably within the professional purview of psychologists, suggesting that our field is complicit with a system that is damaging to the welfare of many persons. The complexities of the intersection of mental health care and the criminal legal system are further pronounced for psychologists working in correctional or legal settings, in which many clients are Black (OJJDP, 2019). Advocating for individual clients and for the disrupting and dismantling of the larger systems in which these clients are placed (e.g., incarceration, welfare) is at times in competition with psychologists’ responsibilities as employees of correctional or legal settings. We review the specific issues that arise from the dual roles of psychologists in these settings and the deleterious overlap of mental health crisis response and the criminal legal system more broadly. We then highlight ways in which psychologists can actively strive to mitigate associated harms.

Systemic Biasing in Forensic Evaluations

Psychologists have myriad responsibilities in correctional and justice system settings, including: evaluating justice-involved individuals through psychological, forensic, and immigration assessments; treating mental, behavioral, and criminogenic concerns; managing and coordinating care within an interdisciplinary team (e.g., crisis intervention); and consulting on staff training and organizational culture. Such complex roles can lead to competing ethical demands, which can become anti-therapeutic in these coercive environments. Specifically, clients are at substantial disadvantage of power beyond the typical therapist-client dynamic by nature of their incarceration and legal involvement (Birgen & Perlin, 2009).

A central role of many forensic psychologists is to conduct psycho-legal evaluations at the request of attorneys or the criminal, civil, or family court. These evaluations are used to make significant decisions about a person’s legal future. Despite the weight that these assessments can hold, forensic psychologists are expected to provide an unbiased and objective opinion based on data collected in an evaluation (APA, 2013; Heilbrun, Grisso, & Goldstein, 2009). Risk assessment tools were developed as a structured guide with which to make a professional judgment on potential future risk of dangerousness or legal involvement. Forensic psychologists use risk assessment measures for many psycho-legal questions, such as in the transfer of juvenile defendants to the criminal legal system and sentencing. These tools are increasingly used in the correctional systems in sentencing decisions (Garrett & Monahan, 2020). Some policy makers and researchers believe that using such measures will reduce the number of detained or incarcerated individuals, as they will provide information on rehabilitative needs and guidance for those not at highest risk for reoffending (Kopkin et al., 2017). However, risk assessment measures often rely on static factors (e.g., criminal history, early antisocial behavior; Kraemer et al. 2001; Durose et al., 2014) that are inherently racially biased (Barry-Jester et al., 2015). For example, Black people are more likely to be arrested compared to White individuals who commit similar crimes (Rovner, 2016; Centers for Disease Control, 2019). Further exacerbating these rates of arrest is high levels of policing in Black communities (Crutchfield et al., 2012; Fagan et al., 2016). Therefore, risk assessment measures that use previous arrests likely selectively increase the overall risk scores of Black people, leading to longer and harsher sentences. Additionally, some risk assessment measures assign risk based on variables that have historically served as proxies for race, such as the presence of a single-parent home (e.g., VRAG; Kröner et al., 2007). Taken together, the construct validity of such risk assessment measures can and should be called into question, as anti-Black racism contributes disproportionate variance across racial groups. Given that the assignment of risk and consequent legal sequelae rely on factors that are likely biased against Black communities, forensic psychologists should be especially critical of the potential mischaracterization and overcriminalization of Black clients.

The Blurry Therapeutic Line

Psychologists can be put into a complicated position when working with Black people who are currently involved, or have a history of involvement, in the criminal legal system. Psychologists in these contexts may be expected to act in ways that clash with the ethical principles and standards set forth by the field. Consider the following example from a clinician who worked in an outpatient program for youth adjudicated of a sexual offense:

“As part of their treatment, all clients were expected to admit to their offense and develop a narrative detailing their actions, but some clients denied. Although some clients who denied their offenses certainly appeared to want to avoid assuming responsibility, there were absolutely cases in which I wondered if the teen was telling the truth and had been wrongly convicted. However, my role as a clinician was simply to help my clients accept responsibility for their actions, identify any thoughts or feelings that contributed to unhealthy choices, and help prevent future engagement in these behaviors. To fulfill my role, I had to assume that the system had made a correct decision and ignore everything I know about the flaws of our criminal justice system, including the pervasiveness of racial disparities in conviction and sentencing rates.”

And this example from a clinician who worked in an outpatient clinic contracted by a specialty court focused on the successful reentry of recently released individuals to provide cognitive behavioral therapy:

“Working in a clinic in which clients were referred to treatment as a part of their participation in a specialty court was, at times, complicated. Though clients were technically volunteering to participate in treatment, the Court would see any missed appointments as noncompliance with the expectations of therapy and, with repeated missed appointments, set forth a series of sanctions on the individual. This put us as clinicians in a tough spot: how do we encourage “voluntary” participation in treatment when the Court is threatening to impose sanctions based on their interpretation of the events? Further, how do we assert our independence from the Court in the treatment room to promote an environment of trust and rapport when our required reporting of missed appointments can lead to sanctions? As much as we tried as therapists to advocate for our clients by explaining the normative difficulty of engaging in treatment, we had a fine line to walk given our involvement with the Court’s contract.”

As described above, therapists involved in court-mandated treatment programs are often asked to attempt to achieve a challenging balance. They must aim to remain true to their roles as clinicians while trying to avoid further perpetuating legal-system involvement by having to report on or impose consequences for clients not complying with the expectations set forth for engagement in treatment. Therapists in criminal legal system settings may run into the common need to disentangle compliance with treatment from the court’s perspective (e.g., attending therapy) from meaningful therapeutic engagement or progress. Similarly, therapists may have to explicate various reasons behind disengagement in services, from the desire to exert control and freedom over their therapeutic treatment to everyday issues of accessibility (e.g., inflexible work hours, lack of transportation) that may be exacerbated by court-involvement.

More complicated, indeed, are therapeutic roles inside jails, prisons, and detention centers, in which a therapist is hired as a corrections officer (CO). According to the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), psychologists working in a correctional facility “function first and foremost as correctional workers” in emergency situations (US Department of Justice, Bureau of Prisons, 2016, Section 3(d)). The BOP acknowledges that in non-emergent situations, psychologists are cautioned to avoid violations of the APA Ethical Code. Such a distinction indicates that the expectations of correctional psychologists in emergency situations may directly compete with those of the ethical guidelines under which psychologists practice. Furthermore, the standards do not specifically address key issues such as (a) psychologists’ correctional versus mental health duties and (b) what is meant by an “emergency” situation. With the title of both psychologist and correctional officer as well as the expectation that the role of correctional officer comes first in emergency situations, inmates may have difficulties perceiving their clinician as someone who they can trust. This may be especially true given the often problematic and challenging relationships between inmates and COs. Psychologists who work within correctional settings have the ethical challenge of balancing the rights of the clients (the inmates) and the rights of the community in which they are employed (the correctional institution; Birgden & Perlin, 2009). Furthermore, there is a significant imbalance of power within the therapeutic relationship between psychologists and incarcerated individuals. In an extreme example, psychologists may be retained to assess an individual’s competence for execution. Despite the ethical principle of beneficence and nonmaleficence set forth by the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA 2016), the outcome of said evaluation may provide the correctional institution or court with evidence with which to carry out an execution of clients. In a less extreme example, psychologists providing treatment in correctional settings may elicit information from incarcerated individuals that, if reported to the institution based on the expectations and reporting statutes of the psychologist’s practice within the facility, could warrant further sanctions placed on individuals. Taken together, psychologists providing mental healthcare within correctional facilities are forced into a complicated dyad of provider and enforcer, a role that may significantly disrupt their therapeutic alliance with and buy-in from their incarcerated clients. The complexities of this dual-role can compromise the value of the service as well as the integrity of its usefulness for mental health treatment.

While there is certainly a need for mental health services for individuals involved in the criminal legal system, psychologists must take caution to consider how best to provide these services while maintaining their therapeutic role in an ethical way. Importantly, psychologists are positioned to go beyond advocating against harmful consequences of working within specific therapeutic and evaluative contexts in the criminal legal system. They should additionally advocate for positive change across the system by using our expertise in mental health and human behavior. Thus, we now turn to the responsibility of psychologists to advocate for the divestment from police involvement in mental health crisis response.

Divesting From Police Involvement in Mental Health Crisis Response

While it is crucial to assess mental health providers’ contributions to the criminal legal system, we must also critically examine the involvement of police in mental health response. Specifically, we must recognize that racially-biased conceptualizations of both criminality and mental illness influence real-world consequences that reinforce the oppression of Black people (see Figure 1). At present, police are deeply ingrained in the picture of mental health in the United States. In addition to serving as frontline responders to mental health crisis calls and their presence in psychiatric hospitals (e.g., Deidrich et al., 2020; Rosenthal, 2021), they are embedded in a system of mass incarceration that is not only a major issue in and of itself but that affects disproportionate numbers of individuals with mental illness and Black people (Blakenship et al 2018; Slate et al., 2013; Subramanian et al. 2018; Vogel et al., 2014; Zaw et al. 2016). Below we elaborate on the negative consequences of police involvement in mental health crisis response, underscore the need to invest in alternative systems of care, and describe specific ways in which psychologists can foster necessary change.

Detrimental Consequences of Police Involvement in Mental Health Response

Police involvement in mental health response puts individuals at risk of physical violence via excessive use of force and, at worst, heinously results in the death of those individuals. Shockingly, no less than a quarter of fatal police shootings are of individuals with mental illness, with some estimates suggesting up to 58% (Bouchard, 2012; DeGue et al., 2016). Framed differently, people with untreated mental illness are 16 times more likely to be killed during a police encounter than individuals without a mental health disorder (Fuller et al., 2015). Moreover, people perceived as having a substance use disorder and a co-occurring disorder are significantly more likely to be characterized as resistant and to have force used against them in police encounters than individuals perceived as having a single mental health disorder or no mental health disorder (Morabito et al., 2017). Taken together, these findings indicate that police are not equipped to care safely and effectively for community members with complex psychiatric presentations. Notably, public support (based on a mixed-race community sample) for police use of force against individuals with mental illness differs by race. In particular, support for use of force is increased when Black suspected criminals have mental illness (as compared to having no mental illness), whereas support is decreased when White suspected criminals have mental illness (Kahn et al., 2017). This public support for use of force against Black people with mental illness, in tandem with increased risk of lethal force (Kramer, 2018) and death by police violence (Edwards et al., 2019) among Black people, highlights that police involvement in mental health crisis response has particularly damaging consequences for Black people.

Both having negative encounters with police and fearing being a potential victim of police brutality are associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and trauma (Alang et al., 2021; Bowleg et al., 2020; Geller et al., 2014). Vicarious exposure to police violence is associated with physiological stress and increased poor mental health days among Black youth and adults, respectively (Browning et al, 2021; Bor et al., 2018). Additionally, having a family member involved in an encounter with police is related to increased depressive and anxiety symptoms over time (Turney et al., 2021). Thus, the criminal legal system has negative physical and mental health impacts, particularly for Black people, through both direct encounters and vicarious exposures to police involvement. Being Black is also associated with greater levels of dissatisfaction and distrust of the police compared to levels of dissatisfaction and distrust found among White people (Hurst et al., 2000). Individuals who identify as having a mental illness similarly have elevated levels of distrust compared to the general population (Thompson & Kahn, 2016). While this elevated distrust is unsurprising given the increased rates of arrest and police violence against Black people and those with mental illness, it highlights the problematic nature of police involvement in mental health crisis response. That is, individuals who justifiably do not trust police have limited options for requesting and receiving trusted support when they experience or encounter a mental health crisis. Beyond the horrific rates of violence and concerning contributions to mental health symptoms, police response to mental health crises often leads to inaccurate assessment and disposition (Lurigio & Watson, 2010). The absence of expertise in mental health conditions and lack of standards for training and evaluating practices of cultural humility among those responding to mental health crisis calls (Hails & Borum, 2003; Fiske et al. 2020; Moon et al., 2018), combined with insufficient structures to support inpatient care needs, has contributed to the criminal legal system becoming a catchall for individuals missed by actual systems of mental health support (Lamb & Weinberger, 2005; Teplin 2000). Clearly a different system is needed.

Establishing Alternative Systems of Community-Based Mental Health Response

Community-based responders to mental health crises should have significant training to support humane and effective responses. Mental health crisis response requires skills in de-escalation, crisis stabilization, accurate assessment of the presenting psychological concern and appropriate level of care, and connection to the care services indicated. To date, there has been great variability in the mental health training afforded to law enforcement personnel involved in mental health response (Hails & Borum, 2003). In a recent national survey of police mental health training, police departments on average rated their effectiveness in responding to mental health crises as a 3.5 on a scale of 1 (not at all effective) to 5 (extremely effective; Fiske et al. 2021). Given the high stakes of mental health crisis encounters – which can involve suicidal ideation, trauma reactions, paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations, among other concerns – our standard of care ought to be higher than one of police-reported moderate effectiveness. Progress in establishing alternative systems of community-based mental health response is likely to benefit greatly from the involvement of psychologists. Psychologists are well-equipped to serve as frontline responders, to train mental health response teams, and to facilitate data-driven improvements in care. Of course, mental health specialists other than psychologists are also suited to effectively contribute to alternative systems of community-based mental health response.

Fortunately, there are models of effective community-based mental health response that rely on mental health specialists rather than on police (Klukoff et al., 2021). For example, in Eugene, Oregon, calls to the police that are identified as non-violent and involving a behavioral health issue are diverted to the Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) program. Through this program, interdisciplinary pairs of crisis specialists and medics serve as frontline responders. Of the tens of thousands of calls CAHOOTS responded to in 2019, approximately 99% were fulfilled without the request of police assistance (Beck et al., 2020a). The Denver Support Team Assisted Response (STAR) program established in 2020 similarly relies on pairs of mental health clinicians and paramedics to respond to nonviolent mental health calls. Police assistance was not required for any of the hundreds of calls responded to in the first six months of STAR (STAR, 2021). In fact, through a preregistered quasi-experimental analysis, the STAR program was shown to prevent over 1,000 criminal offenses during the six months for which data were gathered. These data suggested that the program not only reduced the number of crimes reported by the first-responders but also the actual number of crimes committed during that time period (Dee & Pine, 2022). Olympia, Washington offers an additional example of an alternative system of mental health response with its Crisis Response Unit (CRU). CRU leverages teams of behavioral health specialists who, in addition to responding to mental health crisis calls, regularly engage with community members to enhance trust and build relationships (Beck et al., 2020b; Crisis Response & Peer Navigators, n.d).

Although some non-police mental health response programs have existed for decades (e.g., CAHOOTS was established in 1989), most have been developed within recent years (e.g., Lukert, 2022). Based on extant reports from these programs, it appears that non-police responders can indeed effectively address mental health calls in the community and likely mitigate the arrests (and potential violence and/or death) that often otherwise result from such encounters. Research is needed to optimize the success of such programs, and additional resources should be funneled into the development of non-police community-based mental health crisis response systems across the nation. Certainly, psychologists have a role to play in the process of developing, implementing, and maintaining these alternative systems of care (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Recommendations for Addressing the Harmful Interplay between Mental Health Care and Criminal Justice

| Initiative | Action |

|---|---|

| Enhancing care for justice-involved individuals |

Forensic Evaluation Contexts • Describe relevant risks and needs beyond the use of a risk assessment measure, especially considering areas in which risk assessment measures may overestimate risk based on race (see Riggs-Romaine & Kavanaugh, 2019) • Consider the risks and needs of an individual client in light of the systemic factors that may contribute to recidivism and further penetration into the justice system (e.g., community policing) • Consider how to be culturally sensitive in assessments and acknowledge biases against BIPOC individuals within risk assessments: Include information about a client’s race and ethnic backgrounds in the historical and background sections of a report, in a matter similar to discussing a history of trauma or information about an individual’s housing/community, rather than simply including it in the first line of identifiers (e.g., name, race, age, gender of the client; APLS Practice Committee, 2021) • Do not attempt to remain “color blind” out of a desire to be “objective”, as doing so can be especially harmful to the individuals with whom we work by demonstrating an increase in racial bias (Richeson & Nussbaum, 2004; Holoien & Shelton, 2012) and a reduction in trust legitimacy of evaluators by Black individuals (Apfelbaum, Sommers, & Norton, 2008) |

|

Therapeutic Contexts • Establish relationships with community partners to foster warm hand-offs to quality mental health care for individuals re-entering the community after incarceration or for those actively justice-involved but not incarcerated (e.g., on parole or probation) • Acknowledge and attempt to disentangle the role(s) that forensic psychologists fill openly with justice-involved clients in early sessions of therapy • Act with therapeutic jurisprudence - i.e., supporting the “overarching dignity of clients and the community while attending to the core values of freedom and well-being” of justice involved individuals (Birgen & Perlin, 2009, p. 262) - in order to deliver services in correctional institutions with the promotion of human values as enacted in law (for a lengthy discussion on therapeutic jurisprudence, see Birgen & Perlin, 2009) • Recognize the ways in which the correctional system and the businesses that profit within the system may affect the roles psychologists are asked to play • Become familiar with and adhere to the Specialty Guidelines of Forensic Psychology (APA, 2013) and Standards for Psychology Services in Jails, Prisons, Correctional Facilities, and Agencies (IACFP, 2010), which discuss expectations, principles, and specific actions by which forensic and correctional psychologists should work within the adversarial and, at times, coercive systems, with a focus on minimizing emotional and physical harm and maximizing competence in mental health service delivery • Increase access to practica opportunities in forensic settings for trainees, ensuring that the above recommendations are incorporated into training and supervision • Develop measurable clinical competencies based on the above recommendations to appropriately evaluate trainees in forensic settings | |

| Divest from police involvement in mental health response |

• Leverage professional networks to compose a joint letter or petition for policy-makers calling for divestment from police, investment in community-based crisis response staffed by trained mental health professionals, and increased funding for mental health programming more broadly • Develop and conduct surveys of police presence - and employee and client psychological experiences of police presence - in psychologists’ workplaces and local mental health establishments |

| Establish alternative systems of community-based mental health response |