Abstract

Background:

Allergy to penicillin is commonly reported in many countries and is an overwhelming global public health concern. Penicillin allergy labels can lead to the use of less effective antibiotics and can be associated with antimicrobial resistance. Appropriate assessment of suspected penicillin allergy (often including skin testing, followed by drug provocation testing [DPT] performed by allergists) can prevent the unnecessary restriction of penicillin or delabelling. Many countries in the Asia Pacific (AP) have very limited access to allergy services, and there are significant disparities in the methods of evaluating penicillin allergy. Therefore, a clinical pathway for the management of penicillin allergy is essential.

Objectives:

To develop a risk-stratified clinical pathway for delabeling penicillin allergy, taking into account the distinct epidemiology, patient/sensitization profiles, and disparities of allergy services or facilities within the AP.

Methods:

A risk-stratified penicillin allergy delabeling clinical pathway was formulated by the Drug Allergy Committee of the Asia Pacific Association of Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology. and members of the Penicillin Allergy Disparities survey in AP each representing one country/region of the AP. The clinical pathway was tested based on a database of anonymized patients who were sequentially referred for and completed penicillin allergy evaluation in Hong Kong.

Results:

The clinical pathway was piloted employing a “hub-and-spoke” approach to foster multidisciplinary collaboration between allergists and nonallergists. A simulation run of the algorithm on a retrospective Hong Kong cohort of 439 patients was performed. Overall, 367 (84%) of patients were suitable for direct DPT and reduced the need for skin testing or specialist’s care for 357 (97%) skin test-negative individuals. Out of the skin test-negative patients, 345 (94%) patients had a negative DPT.

Conclusions:

This risk-stratification strategy for direct oral DPT can reduce the need for unnecessary skin testing in patients with low-risk penicillin allergy histories. The hub and spoke model of care may be considered for further piloting and validation in other AP populations that lack adequately trained allergists.

Keywords: Allergy, delabeling, penicillin, stewardship

1. Introduction

Penicillin is the most widely prescribed of all antibiotics but also the most implicated culprit for self-reported drug allergies, which lead to a drug allergy label when people present to healthcare services [1–3]. However, most allergy labels to penicillin are found to be incorrect, with only around 5% to 15% confirmed to be genuine after appropriate penicillin allergy evaluation globally [4–6]. Incorrectly labeled penicillin “allergy” leads to the obligatory use of broader-spectrum and second-line antibiotics and is associated with a myriad of adverse clinical outcomes, including the development of multidrug-resistant organisms and increased healthcare utilization [7–11]. Delabeling incorrect penicillin allergies has become a cornerstone in antimicrobial stewardship and has proven to improve patient outcomes and reduce health care costs. However, investigation of unconfirmed penicillin allergy has traditionally required evaluation (often including skin testing, followed by drug provocation testing [DPT, also known as “drug challenge”]) performed by allergists [12, 13]. Systematic reviews of studies in adults and children have shown the overall safety of direct oral provocation using penicillin or amoxicillin in delabeling incorrect penicillin allergies [14, 15].

The overwhelming burden of incorrect penicillin allergy labels remains a global public health concern. In the Asia-Pacific (AP) region, around 5% to 10% of the population carries a drug allergy label, with penicillins being the most implicated culprit [16]. However, there are unique differences in epidemiology, patient/cultural characteristics, sensitization patterns, and healthcare infrastructures which render “international” guidelines less applicable [17, 18]. For example, the incidence of “big gun” (broad-spectrum) penicillin allergy and the rate of monosensitization to major/minor penicillin determinants seem to be significantly higher than in Western cohorts [2, 19]. Some regions still advocate for “preemptive” routine penicillin allergy skin testing among patients without a history of penicillin allergy (or even exposure), leading to high false-positive rates and inappropriate labeling [20]. Especially in emerging economies, as in many AP countries, there is limited access to allergy services or specialists, which further hinders the capacity for penicillin allergy delabeling [16, 21].

To overcome these issues, delabeling strategies leveraging risk stratification, multidisciplinary collaboration, and direct DPT have been successfully implemented in a few countries across the AP. For example, a pediatric center in Singapore reported that prior skin tests may not be necessary for children with a history of nonsevere reactions and could safely proceed with direct penicillin DPT [22]. In adult patients, a multicenter Australian study determined criteria to effectively triage low- and high-risk patients for out-patient direct oral penicillin DPT to facilitate effective delabeling [2, 23] The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy also recommends that low-risk cases in both adults and children can be delabelled following direct penicillin DPT without the need for specialist assessment (https://www.allergy.org.au/images/stories/hp/info/ASCIA_HP_Consensus_Penicillin_Allergy_2020.pdf). Similarly, Hong Kong established its territory-wide penicillin delabeling initiative which demonstrated that its nurse-led, protocol-driven evaluation was safe and effective in penicillin allergy delabeling [24]. Subsequently, local guidelines were published to empower nonallergists to independently perform delabeling at “spoke” clinics, supported by allergists in the “hub” (employing a “hub and spoke” model) [25]. Of note, the “spoke” clinics in Hong Kong comprised specialists and nonspecialists from the rheumatology and infectious diseases divisions in public hospitals with an interest in clinical immunology/allergy.

Despite the success of individual centers, there remains significant variation in the strategies implemented across different countries, and the AP does not yet have its own regional recommendations on penicillin allergy testing or delabeling. There are also no uniform definitions of “low-risk” patients or diagnostic protocols in most countries, although the majority of referred patients are deemed to be suitable for direct DPT [13, 24, 26]. The strategy of direct penicillin DPT among low-risk patients is especially useful, given the deficiency in allergist services or facilities in many AP countries. Regulatory and legal restrictions may also prohibit nurses and pharmacists in different countries from carrying out nurse-led, physician-sanctioned protocols. Therefore, as a follow-up to an earlier Asia Pacific Association of Allergy Asthma and Clinical Immunology survey on disparities and inequalities of penicillin allergy in the AP region, the Drug Allergy Committee aimed to develop a risk-stratified penicillin allergy delabeling algorithm using direct DPT for delabeling incorrect penicillin allergy labels. Leveraging on their clinical experience in their practicing countries, the clinical pathways algorithm took into account the distinct epidemiology, patient/sensitization profiles, as well as disparities of allergy services or facilities within the AP. An agreement among members of the group approach was used instead of the usual Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation approach due to the paucity of reported literature on direct penicillin provocation in the AP region, and the urgent need for a pragmatic strategy that should take into account the individual healthcare infrastructures of each participating country/region.

2. Methods

In the first round, an initial draft and framework of the clinical pathways were put together by P.H.L., B.Y.H.T., and M.L. In the second round, the initial draft was circulated among the group for review and revision, with discussion among all members open between May and July 2023. Multiple rounds of amendments and modifications were implemented, with revisions made until agreement was reached with every member of the group agreeing to the final version.

Risk stratification of the index reaction which resulted in the penicillin allergy label was classified into 3 categories: low risk, other features, and high risk (Table 1). “Low-risk index reactions” comprised symptoms and signs where the likelihood of drug allergy was unlikely as the risk was no different from the general population. “High-risk index reactions” comprised objective symptoms and signs consistent with an immunologically mediated, allergic reaction. “Other features” comprised symptoms and signs that may or may not be suggestive of drug allergy.

Table 1.

Low- and high-risk features during the evaluation of penicillin allergy

| Low-risk features | High-risk features |

|---|---|

|

|

Risk similar to the general population, may consider directly delabeling in certain settings.

The “hub” was defined as the hospital with an established specialist clinical immunology/allergy service recognized by the local government, ministry of health, or national clinical immunology/allergy society. The “spoke” was defined as the hospital without an established specialist clinical immunology/allergy service but where nonallergist services could provide a similar level of care with training, preceptorship, and accreditation by the “hub.” The hubs and spokes could be supported by nurses or pharmacists trained by allergists from the hubs in carrying out oral direct provocation tests. Where local legislation allowed, nurse- or pharmacist-led, risk-stratified direct provocation testing could be carried out with or without direct allergist supervision.

The proposed clinical pathway was then retrospectively tested through a simulation run based on a historical database of anonymized patients who were sequentially referred for and completed penicillin allergy evaluation in Hong Kong between May 2022 and March 2023. All patients had complete allergy histories for risk stratification and penicillin skin testing, and, if negative, DPT results. All patients gave informed consent. This historical cohort was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster.

3. Results

3.1. Asia Pacific clinical pathway on direct oral provocation for delabeling penicillin allergy

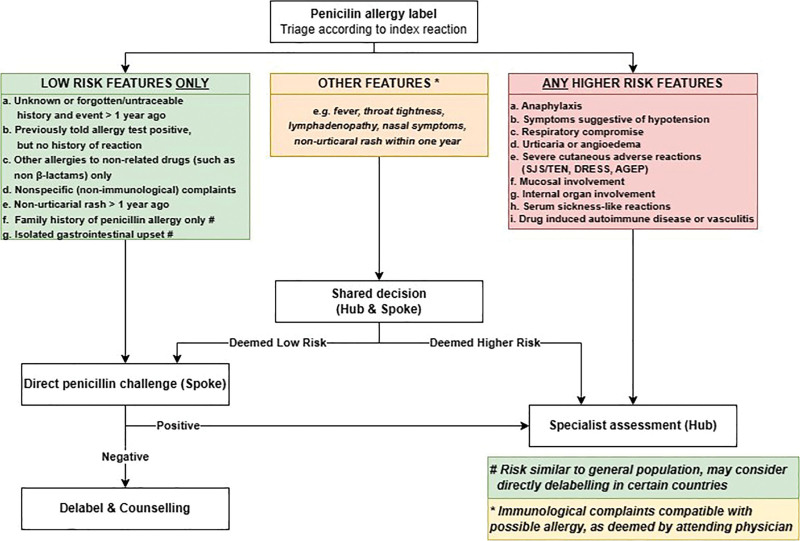

The AP clinical pathway on direct DPT for delabeling penicillin allergy is graphically summarized in Figure 1. The aim was to provide a framework to assist in establishing “hub-and-spoke” networks where delivery of penicillin allergy delabeling services can be performed independently by nonallergists at “spoke” centers who are supported by allergists/physicians experienced in drug allergy testing at “hub” centers. Recommendations pertain to both children and adults, although the dose of medication used for DPT should be age-adjusted.

Figure 1.

Summary of the AP Clinical pathway on direct DPT for delabelling penicillin allergy. AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; AP, Asia Pacific; DPT, drug provocation testing; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SJS, Stevens-Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

-

Establishing hub and spoke networks.

Networks of “hub and spoke” centers should be established to facilitate communication and the sharing of expertise, with each spoke center networked with at least one hub center. In the pilot Hong Kong model, the hub and spokes were all within public hospitals.

Designated “spoke” centers should have clinicians with an interest in penicillin allergy delabeling and facilities for DPT (including access to resuscitation equipment/drugs and with relevant personnel trained in the management of anaphylaxis) [25]. The clinicians may comprise specialists or nonspecialists with an interest in and the necessary training in clinical immunology/allergy.

Designated “hub” centers should have specialists experienced in drug allergy testing (preferably an allergist/immunologist with a special interest in drug allergy) who can offer advice, training, and support for spoke centers.

-

Exclusion criteria for spoke centers

- Patients with the following conditions should not be evaluated for direct DPT at spoke centers but instead have their evaluations deferred or be referred to a hub center:

- Pregnancy;

- Immunocompromised patient (or on systemic immunosuppression in the past 4 weeks);

- Unable to withhold medications potentially interfering with DPT (e.g., antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants);

- Uncontrolled asthma, urticaria, or other diseases limiting the use of rescue medications.

-

Risk stratification by spoke centers

A comprehensive drug allergy history, including a review of previous medical and prescription records, should be taken to allow the clinician to risk stratify with reference to the features described in Table 1.

Patients with only “low-risk” features are suitable to proceed with direct DPT at spoke centers.

Patients with any “high-risk” features are not suitable for direct DPT at spoke centers and should be referred to specialists at hub centers for further evaluation.

Patients with other features suggestive of a possible allergy (i.e., not specified in Table 1) may be suitable for direct DPT at spoke centers, which should be discussed with a networked hub center before proceeding. Unsuitable patients should be referred to hub centers for further evaluation.

Clinicians, nurses, and pharmacists assessing the patients at spoke centers will need to be properly trained, and undergo periodic audits on practice, systems, and processes. Maintenance of competency through continuing medical education is also essential.

-

4.

Direct penicillin provocation at spoke centers

DPT should be performed in an appropriate setting with resuscitation facilities readily accessible and under the supervision of trained personnel.

Medications potentially interfering with DPT (e.g., antihistamines) should be stopped for 7 days before DPT.

The index penicillin should be used for DPT (if known).

If the index penicillin is unknown, DPT should be performed with amoxicillin.

A graded approach to the maximum single dose (e.g., 3-step: 10%, 30%, 60%, or 2-step 10%, 90%) given at 30-minute intervals is recommended.

Patient should be observed at least 1 hour after the final dose of DPT, with clear instructions on what to do if symptoms develop after leaving.

An immediate-type hypersensitivity to the DPT agent is confidently excluded if there is no reaction after >1 hour after completion of DPT.

-

5.

Postprovocation follow-up at spoke centers

Patients should be contacted at least 72 hours later to ensure there were no nonimmediate type manifestations.

A DPT is considered negative if there is no definite reaction after at least 72 hours after the completion of the DPT.

Patients with reported reactions after DPT should be called back for review at spoke centers and treated, if and as necessary.

Patients with equivocal reactions can be offered a repeat DPT or referred to a hub center for further evaluation.

Inaccurate penicillin allergy labels should be delabeled following a negative DPT with proper patient counseling and written documentation (such as a drug allergy notification letter).

3.2. Simulation run of the clinical pathways on retrospective cohort from Hong Kong with suspected penicillin allergy

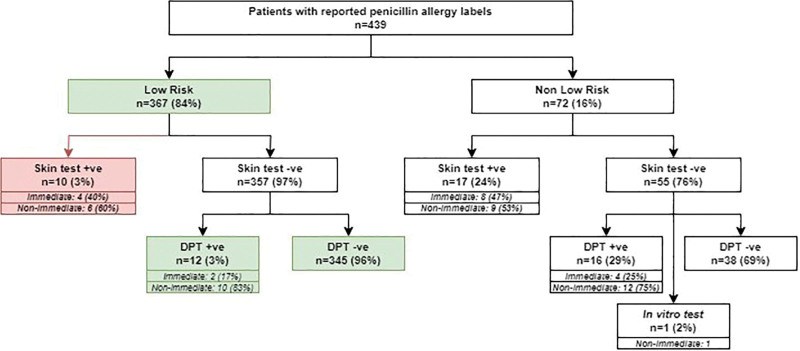

The algorithm was then tested with a cohort of 439 adult Chinese patients (male:female ratio: 1:3, median age: 59 [18–90]) from Hong Kong who had previously completed penicillin allergy evaluation with skin testing and, if negative, DPT. The outcomes of the simulation run are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Simulation run of clinical pathway on 493 patients previously evaluated for penicillin allergy. Green denotes patients who could be diagnosed by direct DPT by nonallergists. Red denotes patients with uncertain outcomes due to a lack of DPT results from retrospective cohort data. AP, Asia Pacific; DPT, drug provocation testing.

Applying the risk-stratification clinical pathway, 367 (84%) of the patient cohort were triaged as low-risk and suitable for direct DPT in spoke centers. Compared with the “traditional” evaluation, the clinical pathway reduced the need for skin testing or specialists’ care for 357 (97%) individuals who were skin test negative. Of the 367 patients, 345 (94%) had a negative DPT. Of the remaining 22 (6%), DPT was not carried out in 10 patients (as they were skin test positive during their original allergy evaluation), and 12 patients (3%) had positive DPT. The majority of positive DPT (10/12, 83%) were of nonimmediate onset and all were mild exanthema, which self-resolved without need for treatment. The 2 (17%) remaining positive DPT were of immediate onset, where both patients reported mild urticaria without systemic symptoms, which fully resolved with oral antihistamines only.

4. Discussion

For risk stratification, we present here the very first clinical pathway on penicillin allergy delabeling for the AP region. Although recommendations for direct DPT have also been published, this algorithm focuses on the AP region and empowers nonallergists working in hospital settings to independently delabel patients without the need for hospitalization [27]. Building upon the experience of one successful hub and spoke model in the AP, we recommend a multidisciplinary collaboration between allergists and nonallergists in triaging low-risk patients for direct DPT [28, 29]. The simulation run of the algorithm on a cohort of genuine patients referred for penicillin allergy evaluation clearly demonstrates the potential of this strategy in mitigating the need for specialists or unnecessary skin testing, as well as the safety of direct DPT after risk stratification. More than 94% of patients could be delabeled after direct DPT, with 3% experiencing only very minor DPT reactions and the remaining 3% unknown (as DPT was not performed due to a positive skin test). Freeing up the unnecessary need for skin testing among low-risk patients is particularly beneficial in the AP region, given the problems with continuous access to penicillin skin testing reagents (which may not even be registered in some countries) and the need for preparation by pharmacists. It would also alleviate the need to maintain quality control of inventory/storage of skin testing products, and the technique and interpretation among healthcare professionals.

There are several limitations to this algorithm. First, there will be individual variations in practice across different countries, cultures, and healthcare infrastructures within the AP. For example, patients with only a family history of penicillin allergy (but no history of reaction to penicillin themselves) or a history of isolated gastrointestinal symptoms are considered to be at similar risk as the general population and may be directly delabeled in certain countries without the need for DPT. Also, low-risk penicillin allergy history could undergo DPT to have their allergy label safely removed. However, some centers may prefer to proceed with a direct DPT to reassure patients of tolerance, as well as formal documentation out of medicolegal necessity. Such variations in practice cannot be addressed in this document, and we suggest that spoke centers seek the expertise and experience of their supporting hubs for country-specific guidance. Second, there are still areas of uncertainty regarding optimal penicillin allergy evaluation, and any recommendations can only serve as general guidance. For example, based on experience from our own region, we classified forgotten/untraceable history or occurrence of nonurticarial rash of more than 1 year ago as “low-risk” features, which contrasts with clinical decision rules validated in other populations that advocate a 5-year cutoff [30]. In the Australian context, patients with an unknown history are also classified as having a higher risk. However, the duration since index reaction is only one of the many dimensions of overall risk assessment, and other factors (e.g., presence or absence of cofactors, or reactions upon repeated exposure) also need to be considered but are beyond the scope of this algorithm. Also, we did not advocate for a “prolonged DPT” for nonimmediate type reactions due to the paucity of evidence and possible unintended risk of promoting antimicrobial resistance. However, such practices remain controversial, and centers may opt for individualized DPT approaches based on the guidance and expertise of their hubs. Third, this algorithm is mainly targeted for nonallergists in spoke centers within public hospitals. The evaluation of nonlow-risk patients should be individualized and based on the expertise of specialists at hub centers, which is beyond the scope of this document. Finally, the simulation run only included a single cohort of Chinese adult patients from a single center who were evaluated by allergists via the “traditional” approach of skin testing with or without DPT. The outcome of DPT or genuine allergy status could not be determined among those patients with positive skin tests, and there is the possibility of false-positive skin tests, including in patients with no previous exposure (sensitization only) to penicillins [19, 31, 32]. Further validation and prospective studies will be required to confirm the algorithm’s external validity for other patient groups. However, based on the collective experience of the panel, we believe the algorithm will likely be effective in other appropriately risk-stratified populations, including both pediatric and adult patients.

We emphasize that this clinical pathway does not represent a set of evidence-based recommendations nor is it a regional consensus, highlighting the need for further research and collaboration among AP countries and the development of an AP consensus. Possible barriers to implementation may also vary between different centers, particularly with the initial establishment and training within the hub and spoke networks. We anticipate that the increased use of telemedicine and standardized electronic-learning materials can be adapted between hub and spoke networks across the AP region in the future. Nonetheless, we hope that this clinical pathway can serve as a unified framework toward establishing more penicillin allergy delabeling facilities and fostering partnerships between allergists and nonallergists within and across regions. With the advent of more region-specific data and expertise, more evidence-based recommendations will allow further refinement of the proposed consensus-based algorithm in the future.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Author contributions

PHL conceptualized and curated the data; PHL, BYHT and ML designed the study and contributed in data analysis; PHL, BYHT, CJ, RCML, HRK, PAM, JM, SM, DLP, TR, MMT, MY and ML participated in data interpretation and manuscript writing; all authors reviewed the paper.

Footnotes

Published online 18 October 2023

Philip Hei Li, Bernard Yu-Hor Thong, and Michaela Lucas contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Macy E. Penicillin and beta-lactam allergy: epidemiology and diagnosis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14:476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li PH, Yeung HHF, Lau CS, Au EYL. Prevalence, incidence, and sensitization profile of beta-lactam antibiotic allergy in Hong Kong. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e204199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Versporten A, Coenen S, Adriaenssens N, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, Vankerckhoven V, Aerts M, Hens N, Molenberghs G, Goossens H. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient penicillin use in Europe (1997-2009). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(Suppl 6):vivi13-vivi23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacco KA, Bates A, Brigham TJ, Imam JS, Burton MC. Clinical outcomes following inpatient penicillin allergy testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2017;72:1288-1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siew LQC, Li PH, Watts TJ, Thomas I, Ue KL, Caballero MR, Rutkowski K, Till SJ, Pillai P, Haque R. Identifying low-risk beta-lactam allergy patients in a UK tertiary centre. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2173-2181.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li PH, Siew LQC, Thomas I, Watts TJ, Ue KL, Rutkowski K, Lau C-S. Beta-lactam allergy in Chinese patients and factors predicting genuine allergy. World Allergy Organ J. 2019;12:100048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li PH, Chung HY, Lau CS. Epidemiology and outcomes of geriatric and non-geriatric patients with drug allergy labels in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2021;27:192-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan SCW, Yeung WWY, Wong JCY, Chui ESH, Lee MSH, Chung HY, Cheung TT, Lau CS, Li PH. Prevalence and impact of reported drug allergies among rheumatology patients. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10:918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong JCY, Cheong N, Lau CS, Li PH. Prevalence and impact of misdiagnosed drug allergy labels among patients with hereditary angioedema. Front Allergy. 2022;3:953117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shenoy ES, Macy E, Rowe T, Blumenthal KG. Evaluation and management of penicillin allergy: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:188-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone CA, Jr, Trubiano J, Coleman DT, Rukasin CRF, Phillips EJ. The challenge of de-labeling penicillin allergy. Allergy. 2020;75:273-288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li TS, Hui HKS, Kan AKC, Yeung MHY, Wong JCY, Chiang V, Li PH. Prospective Assessment of Penicillin Allergy (PAPA): Evaluating the performance of penicillin allergy testing and post-delabelling outcomes among Hong Kong Chinese. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2023. Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chua KYL, Vogrin S, Bury S, Douglas A, Holmes NE, Tan N, Brusco NK, Hall R, Lambros B, Lean J, Stevenson W, Devchand M, Garrett K, Thursky K, Grayson ML, Slavin MA, Phillips EJ, Trubiano JA. The penicillin allergy delabeling program: a multicenter whole-of-hospital health services intervention and comparative effectiveness study. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper L, Harbour J, Sneddon J, Seaton RA. Safety and efficacy of de-labelling penicillin allergy in adults using direct oral challenge: a systematic review. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3:dlaa123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srisuwatchari W, Phinyo P, Chiriac AM, Saokaew S, Kulalert P. The safety of the direct drug provocation test in beta-lactam hypersensitivity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11:506-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li PH, Pawankar R, Thong BYH, Mak HWF, Chan G, Chung W-H, Juan M, Kang H-R, Kim B-K, Lobo RCM, Lucas M, Pham Duy Le, Ranasinghe T, Rengganis I, Rerkpattanapipat T, Sonomjamts M, Tsai Y-G, Wang J-Y, Yamaguchi M, Yun J. Disparities and inequalities of penicillin allergy in the Asia-Pacific region. Allergy. 2023;78:2529-2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mak HWF, Yeung MHY, Wong JCY, Chiang V, Li PH. Differences in beta-lactam and penicillin allergy: beyond the West and focusing on Asia-Pacific. Front Allergy. 2022;3:1059321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thong BY, Lucas M, Kang HR, Chang Y-S, Li PH, Tang MM, Yun J, Fok JS, Kim B-K, Nagao M, Rengganis I, Tsai Y-G, Chung W-H, Yamaguchi M, Rerkpattanapipat T, Kamchaisatian W, Leung TF, Yoon HJ, Zhang L, Abdul Latiff AH, Fujisawa T, Thien F, Castells MC, Demoly P, Wang J-Y, Pawankar R. Drug hypersensitivity reactions in Asia: regional issues and challenges. Asia Pac Allergy. 2020;10:e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong JC, Au EY, Yeung HH, Lau CS, Li PH. Piperacillin-Tazobactam allergies: an exception to usual penicillin allergy. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2021;13:284-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang X, Xiao H, Zhang H, Xu F, Jia Q, Meng J. High false-positive results from routine penicillin skin testing influencing the choice of appropriate antibiotics in China. J Hosp Infect. 2023;134:169-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee TH, Leung TF, Wong G, Ho M, Duque JR, Li PH, Lau C-S, Lam W-F, Wu A, Chan E, Lai C, Lau Y-L. The unmet provision of allergy services in Hong Kong impairs capability for allergy prevention-implications for the Asia Pacific region. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2019;37:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goh SH, Chong KW, Chiang WC, Goh A, Loh W. Outcome of drug provocation testing in children with suspected beta-lactam hypersensitivity. Asia Pacific Allergy. 2021;11:e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson B, Trevenen M, Klinken E, Smith W, Yuson C, Katelaris C, Perram F, Burton P, Yun J, Cai F, Barnes S, Spriggs K, Ojaimi S, Mullins R, Salman S, Martinez P, Murray K, Lucas M. Multicenter Australian study to determine criteria for low- and high-risk penicillin testing in outpatients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:681-689.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kan AKC, Hui HKS, Li TS, Chiang V, Wong JCY, Chan TS, Kwan IYK, Shum WZ, Yeung MSC, Au EYL, Ho CTK, Lau CS, Li PH. Comparative effectiveness, safety, and real-world outcomes of a nurse-led, protocol-driven penicillin allergy evaluation from the Hong Kong Drug Allergy Delabelling Initiative (HK-DADI). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li PH, Wong JCY, Chan JMC, Chik TSH, Chu MY, Ho GCH, Leung WS, Li TCM, Ng YY, Shum R, Sin WWY, Tso EYK, Wu AKL, Au EYL. Hong Kong Drug Allergy Delabelling Initiative (HK-DADI) consensus statements for penicillin allergy testing by nonallergists. Front Allergy. 2022;3:974138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalski ML, Ansotegui I, Aberer W, Al-Ahmad M, Akdis M, Ballmer-Weber BK, Beyer K, Blanca M, Brown S, Bunnag C, Hulett AC, Castells M, Chng HH, De Blay F, Ebisawa M, Fineman S, Golden DBK, Haahtela T, Kaliner M, Katelaris C, Lee BW, Makowska J, Muller U, Mullol J, Oppenheimer J, Park H-S, Parkerson J, Passalacqua G, Pawankar R, Renz H, Rueff F, Sanchez-Borges M, Sastre J, Scadding G, Sicherer S, Tantilipikorn P, Tracy J, van Kempen V, Bohle B, Canonica GW, Caraballo L, Gomez M, Ito K, Jensen-Jarolim E, Larche M, Melioli G, Poulsen LK, Valenta R, Zuberbier T. Risk and safety requirements for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in allergology: World Allergy Organization Statement. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savic L, Ardern-Jones M, Avery A, Cook T, Denman S, Farooque S, Garcez T, Gold R, Jay N, Krishna MT, Leech S, McKibben S, Nasser S, Premchand N, Sandoe J, Sneddon J, Warner A. BSACI guideline for the set-up of penicillin allergy de-labelling services by non-allergists working in a hospital setting. Clin Exp Allergy. 2022;52:1135-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang V, Saha C, Yim J, Au EYL, Kan AKC, Hui KSH, Li TS, Lo WLW, Hong YD, Ye J, Ng C, Ko WWK, Ho CTK, Lau CS, Quan J, Li PH. The Role of the Allergist in Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccine Allergy Safety: a pilot study on a “Hub-and-Spoke” model for population-wide allergy service. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:308-312.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawankar R, Thong BY. A novel allergist-integrative model for vaccine allergy safety. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129:263-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trubiano JA, Vogrin S, Chua KYL, Bourke J, Yun J, Douglas A, Stone CA, Yu R, Groenendijk L, Holmes NE, Phillips EJ. Development and validation of a penicillin allergy clinical decision rule. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:745-752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tannert LK, Falkencrone S, Mortz CG, Bindslev-Jensen C, Skov PS. Is a positive intracutaneous test induced by penicillin mediated by histamine? A cutaneous microdialysis study in penicillin-allergic patients Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grims RH, Kranke B, Aberer W. Pitfalls in drug allergy skin testing: false-positive reactions due to (hidden) additives. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:290-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]