A wide variety of the complementary therapies claim to improve health by producing relaxation. Some use the relaxed state to promote psychological change. Others incorporate movement, stretches, and breathing exercises. Relaxation and “stress management” are found to a certain extent within standard medical practice. They are included here because they are generally not well taught in conventional medical curricula and because of the overlap with other, more clearly complementary, therapies.

Table 1.

| Definitions of terms relating to hypnosis |

|---|

| Hypnotic trance—A deeply relaxed and focused state with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical faculties |

| Direct hypnotic suggestion—Suggestion made to a person in a hypnotic trance that alters behavior or perception while the trance persists (for example, the suggestion that pain is not a problem for a woman under hypnosis during labor) |

| Post-hypnotic suggestion—Suggestion made to a person in a hypnotic trance that alters behavior or perception after the trance ends (for example, the suggestion that in the future, a patient will be able to relax at will and will no longer be troubled by panic attacks) |

TECHNIQUES

Hypnosis

Hypnosis is the induction of a deeply relaxed state, with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical faculties. Once in this state, sometimes called a hypnotic trance, patients are given therapeutic suggestions to encourage changes in behavior or relief of symptoms. For example, in a treatment to stop smoking, a hypnosis practitioner might suggest that the patient will no longer find smoking pleasurable or necessary. Hypnosis for a patient with arthritis might include a suggestion that the pain can be turned down like the volume of a radio.

Some practitioners use hypnosis as an aid to psychotherapy. The rationale is that in the hypnotized state, the conscious mind presents fewer barriers to effective psychotherapeutic exploration, leading to an increased likelihood of psychological insight.

Relaxation and meditation techniques

One well-known example of a relaxation technique is known variously as progressive muscle relaxation, systematic muscle relaxation, and Jacobson relaxation. The patient sits comfortably in a quiet room. He or she then tenses a group of muscles, such as those in the right arm, holds the contraction for 15 seconds, then releases it while breathing out. After a short rest, this sequence is repeated with another set of muscles. In a systematic fashion, major muscle groups are contracted, then allowed to relax. Gradually, different sets of muscle are combined. Patients are encouraged to notice the differences between tension and relaxation.

The Mitchell method involves adopting body positions that are opposite to those associated with anxiety (fingers spread rather than hands clenched, for example). In autogenic training, patients concentrate on experiencing physical sensations, such as warmth and heaviness, in different parts of their bodies in a learned sequence. Other methods encourage the use of diaphragmatic breathing that involves deep and slow abdominal breathing coupled with a conscious attempt to let go of tension during exhalation.

Visualization and imagery techniques involve the induction of a relaxed state followed by the development of a visual image, such as a pleasant scene that enhances the sense of relaxation. These images may be generated by the patient or suggested by the practitioner. In the context of this relaxing setting, patients can also choose to imagine themselves coping more effectively with the stressors in their lives.

Meditation practice focuses on stilling or emptying the mind. Typically, meditators concentrate on their breath or a sound (mantra) they repeat to themselves. They may, alternatively, attempt to reach a state of “detached observation,” in which they are aware of their environment but do not become involved in thinking about it. In meditation, the body remains alert and in an upright position. In addition to formal sitting meditation, patients can be taught mindfulness meditation, which involves bringing a sense of awareness and focus to their involvement in everyday activities.

Yoga practice involves postures, breathing exercises, and meditation aimed at improving mental and physical functioning. Some practitioners understand yoga in terms of traditional Indian medicine, with the postures improving the flow of prana energy around the body. Others see yoga in more conventional terms of muscle stretching and mental relaxation.

Tai chi is a gentle system of exercises originating from China. The best known example is the “solo form,” a series of slow and graceful movements that follow a set pattern. It is said to improve strength, balance, and mental calmness. Qigong (pronounced “chi kung”) is another traditional Chinese system of therapeutic exercises. Practitioners teach meditation, physical movements, and breathing exercises to improve the flow of Qi, the Chinese term for body energy.

WHAT HAPPENS DURING TREATMENT?

Hypnosis

In hypnosis, patients typically see practitioners by themselves for a course of hourly or half-hourly treatments. Some general practitioners and other medical specialists use hypnosis as part of their regular clinical work and follow a longer initial consultation with standard 10- to 15-minute appointments. Patients can be given a post-hypnotic suggestion that enables them to induce self-hypnosis after the treatment course is completed. Some practitioners undertake group hypnosis, treating up to a dozen patients at a time—for example, teaching self-hypnosis to prenatal groups as preparation for labor.

Relaxation and meditation techniques

Most relaxation techniques require daily practice to be effective. A variety of formats for teaching relaxation and meditation exist, including classes as well as individual sessions. Relaxation can be taught in 1 session by conducting and audio taping a relaxation session. Using the audio tape, patients can then practice the techniques daily at home. Methods such as progressive muscle relaxation are easy to learn; yoga, tai chi, and meditation can take years to master completely.

Most relaxation techniques are enjoyable, and many healthy individuals practice them without having particular health problems. Relaxation classes can also play a social function.

Unlike in many other complementary therapies, practitioners of relaxation techniques do not make diagnoses. They may use the conventional diagnoses as described by the patient to tailor the prescribed program appropriately. In many cases, however, the method of treatment does not depend on a precise diagnosis.

THERAPEUTIC SCOPE

The primary applications of hypnosis and relaxation techniques are for anxiety, disorders with a strong psychological component (such as asthma and irritable bowel syndrome), and conditions that can be modulated by levels of arousal (such as pain). They are also commonly used in programs for stress management.

Research evidence

Evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates that hypnosis, relaxation, and meditation techniques can reduce anxiety, particularly that related to stressful situations, such as receiving chemotherapy (see box). They are also effective for insomnia, particularly when the techniques are integrated into a package of cognitive therapy (including, for example, sleep hygiene). A systematic review showed that hypnosis enhances the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for conditions such as phobia, obesity, and anxiety.

Findings from randomized controlled trials support the use of various relaxation techniques for treating both acute and chronic pain, although 2 recent systematic reviews suggest that methodologic flaws may compromise the reliability of these findings. Randomized trials have shown hypnosis is valuable for patients with asthma and irritable bowel syndrome, yoga is helpful for patients with asthma, and tai chi helps to reduce falls and fear of falling in elderly people. Evidence from systematic reviews shows hypnosis and relaxation techniques are probably not of general benefit in stopping smoking or substance misuse or in treating hypertension.,

Table 2.

| Key studies of efficacy |

|---|

| Systematic reviews |

|

| Randomized controlled trials |

|

| Other |

|

Table 3.

| Registering and training organizations |

|---|

| American Society of Clinical Hypnosis |

| 33 West Grand Avenue Suite 402 |

| Chicago, IL 60610 |

| Tel: (312) 645-9810; fax: (312) 645-9818 |

| Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis |

| Washington State University |

| PO Box 642114 |

| Pullman, WA 99164-2114 |

| www.sunsite.utk.edu/IJCEH/scehframe.htm |

| Other useful addresses |

| American Psychological Association |

| 750 First Street NE |

| Washington, DC 20002-4242 |

| Tel: (202) 336-5500 |

| National Association of Social Workers |

| 750 First Street NE, Suite 700 |

| Washington, DC 20002-4241 |

| Tel: (202) 408-8600, (800) 638-8799 |

Cancer patients use relaxation and hypnosis. Evidence from randomized trials shows hypnosis and relaxation are effective for cancer-related anxiety, pain, nausea, and vomiting, particularly in children. Some practitioners also claim that relaxation techniques, particularly the use of imagery, can prolong life, although currently available evidence is insufficient to support this claim.

SAFETY

Adverse events resulting from relaxation techniques are uncommon. Rare reports describe basilar or vertebral artery occlusion after yoga postures that put particular strain on the neck. People with poorly controlled cardiovascular disease should avoid progressive muscle relaxation because abdominal tensing can cause the Valsalva response. Patients with a history of psychosis or epilepsy have reportedly had further acute episodes after deep and prolonged meditation.

Hypnosis or deep relaxation can sometimes exacerbate psychological problems—for example, by retraumatizing those with post-traumatic disorders or by inducing “false memories” in psychologically susceptible individuals. Evidence, although inconclusive, has raised concerns that the dissociation necessary to participate in relaxation or hypnosis can lead to the manifestation of the symptoms of psychosis. Only appropriately trained and experienced practitioners should undertake hypnosis. Its use should be avoided in patients with borderline personality disorder, dissociative disorders, or with patients who have histories of profound abuse. Competent hypnotherapists are skilled in recognizing and referring patients with these conditions.

PRACTICE

Relaxation techniques are often integrated into other health care practices; they may be included in programs of cognitive behavioral therapy in pain clinics or occupational therapy in psychiatric units. Complementary therapists, including osteopaths and massage therapists, may include some relaxation techniques in their work. Some nurses use relaxation techniques in the acute care setting, such as to prepare patients for surgery, and in a few general practices, classes in relaxation, yoga, or tai chi are regularly available.

Regulation

The practice of many relaxation techniques is poorly regulated, and standards of practice and training are variable. This situation is unsatisfactory, but given that many relaxation techniques are relatively benign, the problem with this variation in standards is more in ensuring effective treatment and good professional conduct than in avoiding adverse effects. By selecting a license mental health professional (psychologist or social worker), patients are more likely to receive treatment from individuals who are well trained in the appropriate use of behavioral techniques.

Poor regulation of hypnosis and deeper relaxation techniques is more serious. Although several professional organizations exist, these groups do not regulate or certify practitioners in hypnotherapy or relaxation. Hypnotherapists with a conventional health care background (such as psychologists, physicians, dentists, and nurses) are regulated by their professional regulatory bodies. Psychotherapists who use hypnotherapy as an adjunctive treatment modality require appropriate training. Individuals who have received a master's degree in counseling or social work or a doctorate in clinical or counseling psychology will be likely to have received appropriate training and supervision.

Training

Although most practitioners receive their training in hypnotherapy or relaxation as a part of their academic training, the American Society of Clinical Hypnosis and the Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis maintain training programs as well as a registry of practitioners (see previous box). Training in teaching relaxation techniques is provided through various routes from self-teaching and apprenticeships to a number of short courses. Many yoga centers also teach relaxation and offer courses to train yoga teachers.

Table 4.

| Further reading |

|---|

| Wright M. Clinical Practice of Hypnotherapy. New York: Guilford Press; 1987 |

| Temes R, ed. Medical Hypnosis: An Introduction and Clinical Guide. Medical Guides to Complementary and Alternative Medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. |

| Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. New York: Delta; 1990. |

Figure 1.

Many relaxation techniques aim to increase awareness of areas of chronic unconscious muscle tension. They often involve a conscious attempt to release and relax during exhalation.

BMJ/Ulrike Preuss

Figure 2.

In China, many people practice tai chi on a daily basis for health promotion.

Hutchison Library/Felix Greene

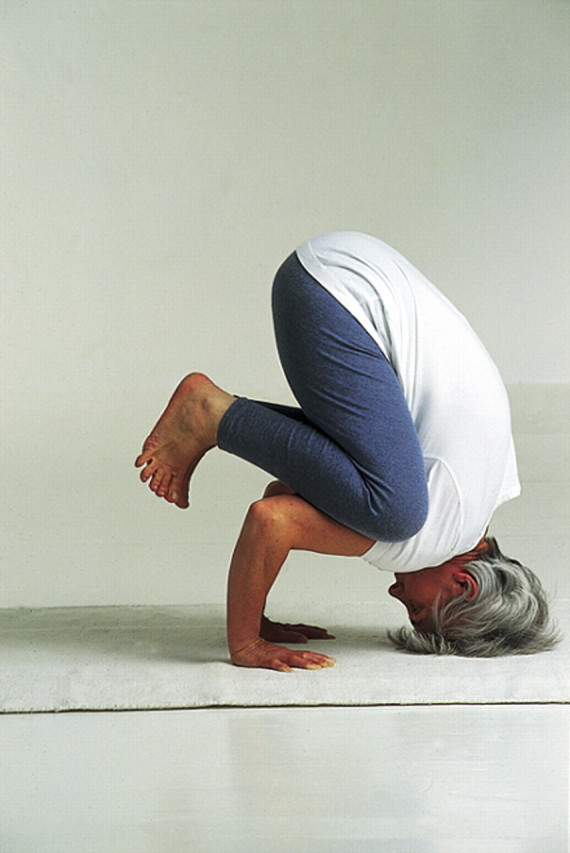

Figure 3.

Basilar or vertebral artery occlusion can occur, albeit rarely, after assuming yoga positions that put stress on the neck.

Collections/Sandra Lousada

Competing interests: None declared

This article was published in BMJ 1999;319:1346-1349. This article is the third in a series originally serialized in BMJ and now available as a book, ABC of Complementary Medicine (ISBN 0 7279 12372), London: BMJ Books; 2000, edited by Drs Zollman and Vickers.

Authors: The ABC of complementary medicine is edited and written by Catherine Zollman and Andrew Vickers. At the time of writing, both authors worked for the Research Council for Complementary Medicine, London.

- Hypnosis is the induction of a deeply relaxed state, with increased suggestibility and suspension of critical facilities, for behavior change or symptom relief

- A wide variety of techniques, such as sequential muscle relaxation, visualization, meditation, yoga, and tai chi, produce mental relaxation, physical relaxation, or both

- Most relaxation techniques need to be practiced daily to be effective. Some techniques, such as sequential muscle relaxation, are easy to learn; others, such as yoga, tai chi, and meditation, take years to master

- Hypnosis and relaxation techniques are used in patients anxiety, disorders with a strong psychological component, and conditions that can be modulated by levels of arousal

- Adverse events from relaxation techniques seem to be uncommon