A century ago, the eugenics movement led to widespread forced sterilization of vulnerable populations. Subsequent moral outrage produced laws that strongly discouraged or prohibited sterilization of the developmentally disabled. Ironically, this legacy may represent a burden for developmentally disabled women today.

We present a fictionalized case of a developmentally disabled woman whose guardian requests surgical sterilization. We review the historical factors that have shaped relevant legal boundaries and discuss medical and ethical issues confronting clinicians in such a situation. We argue that current restrictions on sterilization may be overprotective, thus denying the “best interests” of patients and their families.

CASE HISTORY

Carla is a 24-year-old woman with Down syndrome. She has an IQ of 40. Carla lives with her grandfather and legal guardian, Henry, and has never been institutionalized. Her parents died when she was an infant, and she has no other immediate family. She attends a special needs school.

Carla's medical history includes successful repair of a congenital atrioventricular canal malformation, mild pulmonary hypertension detected echocardiographically, and asthma for which she needs regular use of bronchodilators. Breast development and secondary hair growth are normal.

Carla menstruates monthly and needs assistance to manage her menstrual hygiene. According to psychosocial evaluations, she remains naive about sexuality. Henry keeps Carla out of sex education classes. Carla consistently refuses pelvic examinations because teachers told her “not to lie down with strangers.”

Henry now asks Carla's internist about bilateral tubal ligation for his granddaughter. He broaches sterilization for the first time because of his own age and poor health and because of his concern that after he dies, Carla would not get her current level of supervision. Henry is particularly concerned about sexual assault. He insists on sterilization rather than reversible contraception because he believes Carla would require less monitoring afterward. He worries that the potential medical complications of pregnancy, “could kill” Carla and that life would be “much harder” for her with a baby because future caretakers might not want to be responsible for both mother and child. Henry chose a niece to assume guardianship of Carla after his death but is uncomfortable relying on such a distant relative. Carla does not answer when asked whether she knows she can have babies or if she wants to have a child.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

American eugenicists argued that forced sterilization was in society's best interest. Inspired by the social Darwinism propounded by Francis Galton, many concluded that social ills could result from characteristics transmitted genetically among “unfit” populations. They believed that “defective” people reproduced at higher rates, that criminals and the developmentally disabled tended to have children with similar disorders, and that reproduction among these populations weakened the gene pool.1

In 1907, reflecting the eugenicists' influence, states began enacting laws allowing involuntary sterilization of the developmentally disabled.1 Courts initially declared early sterilization statutes unconstitutional, but support for such legislation grew after World War I. A 1927 Supreme Court ruling upheld these laws. In Buck v Bell, a case of an institutionalized woman who had given birth to an illegitimate child, the court ruled that forced sterilization was constitutional under certain circumstances. Justice Holmes' opinion read:

It is better...if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or...let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those...manifestly unfit from continuing their kind...Three generations of imbeciles is enough.1

Buck v Bell unleashed a wave of forced sterilizations. Whereas physicians had performed 10,877 sterilizations of institutionalized persons through 1928, they performed 27,210 between 1929 and 1941. Public authorities institutionalized some women solely for sterilization and then released them. Between 1907 and 1963, more than 60,000 Americans, mostly women, were sterilized without their consent.1

Forced sterilization fell out of favor after 1940 as Nazi atrocities led to a rejection of eugenic tenets and later due to growing support for civil rights and feminism. In the 1960s, some states repealed sterilization laws. Finally, a scandal involving the sterilization of a developmentally disabled girl without her consent in a federally funded clinic resulted in 1978 guidelines that forbade the use of federal funds for sterilizing anyone younger than 21 years, incompetent, or institutionalized.2 Although Buck v Bell was never overturned, most modern legal scholars consider it bad law.1,3

Given the current legal landscape, it remains extremely difficult to obtain sterilization for an incompetent woman. In Illinois, parents of incompetent children can request sterilization unless challenged by a third party. In other states, courts will not approve sterilization for incompetent persons without enabling legislation. Some states mandate court review and approval for each case.4 In New York City, the charter forbids sterilization of people younger than 21 years or incompetent.5 In 2 instances, New York State allowed sterilization of minors: 1 suffering from painful menses, and the other deemed “unlikely ever to understand...contraception, [who] could be psychologically traumatized if she became pregnant,... gave birth or had pregnancy terminated, and [could] participate in...sexual activities or have...[them]...imposed on her.” But parents of adult incompetent women cannot consent by proxy for sterilization.4

Carla's physician, in consultation with the hospital's legal counsel, advises Henry that local courts would likely refuse petitions to request sterilization.

ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

Legal prohibitions do not relieve clinicians of responsibility for considering relevant medical and ethical issues and from advocating for patients.

Bioethicists generally approve of surrogates making decisions for incompetent patients.6 Courts have recognized that incompetent, developmentally disabled persons must have others make medical decisions for them.3 In Carla's case, the severity of her Down syndrome leads to a court determination that she is incompetent. Henry is appointed her legal guardian. In making decisions for people who have never had capacity, surrogates rely on the best-interest standard.3,4,6 This standard assesses risks and benefits of proposed treatment alternatives, including pain and suffering, and improvement or loss of functioning. Ethical dilemmas may emerge if providers or the state objects to decisions made by surrogates.

DISCUSSION

We draw on Carla's case to suggest that laws designed to protect incompetent people from coercive sterilization may actually infringe on their rights. Courts that allow proxy consent for sterilizations have proposed the following common guidelines. These are consistent with the ethical framework above and with recommendations by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists that have attempted to outline rational sterilization policies.4,7,8

Guidelines for proxy consent sterilization

The patient is permanently incompetent and a court-appointed guardian represents her in full judicial hearings

Carla's mental disability is permanent. She cannot consent voluntarily because she cannot understand the risks and benefits of various alternatives. Henry would have to give proxy consent. Some legal scholars suggest that a court-appointed advocate charged with the responsibility of arguing against sterilization during judicial review would be an important procedural safeguard.3,9

The patient undergoes medical, psychological, and social evaluations

Henry remains willing for Carla to undergo additional evaluations as necessary.

The patient can reproduce but cannot care for offspring

Carla could not care for a child alone. As for her ability to reproduce, Salerno et al reported that of 97 developmentally disabled women who reached menarche, 58 (60%) ovulated.10 Although only some 30 pregnancies in women with Down syndrome have been reported, low pregnancy rates may reflect social and behavioral factors. Furthermore, the majority of these pregnancies resulted in live births. Carla could conceive and give birth.11 She is unlikely to engage in intercourse voluntarily, but her risk of being sexually assaulted is substantial. Forty percent of 104 developmentally disabled women referred to a gynecology clinic were suspected or confirmed victims of such abuse.12 How many pregnancies result from such assaults is not known. Guidelines on sterilization of developmentally disabled women recommend sexual-abuse avoidance counseling,7,8 but this recommendation does not reassure Henry that after he dies, Carla would not be exposed to more people, less supervision, and greater risk.

Sterilization is in the patient's best interest, and she is allowed to express her understanding and opinion of the procedure

Henry does not seek sterilization to treat menometrorrhagia or myomas; some states allow sterilization under such circumstances.4 Instead, for Carla, we must weigh risks and benefits of tubal ligation versus pregnancy. Pregnancy has potential benefits. Carla appreciates the nurturing bond with her grandfather. She might desire to possess a baby, without understanding reproduction. We cannot predict her potential fulfillment in birthing or seeing a child grow, which weighs against the irreversible decision to sterilize her.

Another argument against sterilization is that it deprives patients of sexual autonomy, important in the movement to “mainstream” the developmentally disabled.13 Rights of self-determination, including that of procreative choice, are constitutionally protected, but exercising those rights requires “knowledge and ability to exercise [them] freely.”3 Given that a surrogate would have to facilitate an incompetent patient's right to procreate, how meaningful is the notion of sexual autonomy in such a circumstance? To a large extent, Carla's sexual autonomy was already curtailed when she was denied sex education and told to “never lie down with strangers.” Although families disagree about the wisdom of shielding children from information about sex, we are reluctant to interfere in such family decisions. That caretakers could thus curtail Carla's sexual activity calls into question why sterilization becomes the crucial decision point. We rightly approach invasive interventions with caution but should recognize that less dramatic actions, although engendering little scrutiny, may effectively render patients “infertile” by proxy consent.

Moreover, procreative choice includes both the right to refuse sterilization and the right to choose it. Lachance writes that although “irreversibility sets [sterilization] apart from [temporary] birth control measures... [it]... does not affect the status of the right to choose sterilization as a fundamental right.”9 Blanket prohibitions against sterilization of the mentally incompetent may violate this right. New Jersey's Supreme Court came to the same conclusion in 1979 when it allowed proxy consent for sterilization of an incompetent, developmentally disabled woman.14 The irreversibility of sterilization, however, does obligate us to more rigorously ensure that it is in a patient's best interests.

What are the medical risks? Carla's pulmonary hypertension and asthma raise the possibility of perinatal cardiopulmonary complications. Labor and delivery also tend to be harder for developmentally disabled women because of pelvic abnormalities and difficulty cooperating with instructions.11 Late detection of pregnancy might result in delayed prenatal care. We can only speculate about the psychological risks of pregnancy, birth, or abortion, and the morbidity and mortality risks of pregnancy in any woman are higher than those associated with laparoscopic tubal ligation.15

Beauchamp and Childress wrote that the best-interest standard is “inescapably a quality-of-life criterion.”6 When it comes to sterilization, however, laws supplant subjective consideration of quality-of-life concerns in individual cases. Should we not apply the same ethical standard to proxy decisions for reproductive health as for any other medical issue?3,9

Sterilization is the most practical, least restrictive contraception available

Henry dismisses Carla's use of other contraceptive methods after he dies. Compliance issues rule out barrier methods and lack of adequate supervision would prohibit the use of hormonal contraceptives. Although an intrauterine device is long lasting and has minimal risks,16 Henry worries that complications might occur. He worries about Carla being traumatized by repeated pelvic examinations that require sedation and about Carla's need for supervision should complications occur or when replacement became necessary.

Motivations for requesting sterilization are examined

We must ask what secondary gains might be involved and whether they are in conflict with patients' best interests. Such discussions are invaluable for exploring relevant family concerns.

A survey of 88 parents found that 75 (85%) were willing to consider sterilization for their developmentally disabled children; 8 (10%) requested it.12 Parents cited fear about the efficacy of other methods and about pregnancy, particularly from sexual abuse—reasons similar to those Henry expresses. Few thought their children could want or care for a child. Perhaps most instructive, 85 (97%) said they would want medical staff to help them make the decision but not to decide for them.

Henry first requests sterilization after Carla is well into her reproductive years. Henry seems less concerned with his own convenience than with Carla's welfare after his death. His decision appears to reflect his sincere assessment of Carla's best interests.

CONCLUSION

Laws forbidding sterilization of the mentally incompetent may be nearly as dehumanizing as the forced sterilization laws they replaced. Weighing the complex medical and ethical issues involved, judging whether guardians' fears are reasonable, and determining patients' best interests require careful, individual case reviews with strict procedural safeguards. Families are often the best substitute voice for incompetent adults. Not allowing a caring family to express preferences regarding such life-altering experiences as pregnancy and childbirth may paradoxically silence the patient's voice.

Summary points

Forced sterilization of vulnerable populations in the early 20th century led to legal prohibition of the sterilization of developmentally disabled patients

Sterilization thus represents an exception to customary practice, which allows surrogate decision making for patients without capacity

The law should apply the same ethical standard to proxy decisions for reproductive health, permitting surrogates to make informed decisions for legally incompetent patients

Figure 1.

Mara poses in front of a device for measuring the difference in size between Aryan and non-Aryan skulls, Berlin, 1933.

Roman Vishniac. Gelatin silver print. ©Mara Vishniac Kohn, courtesy of the International Center of Photography

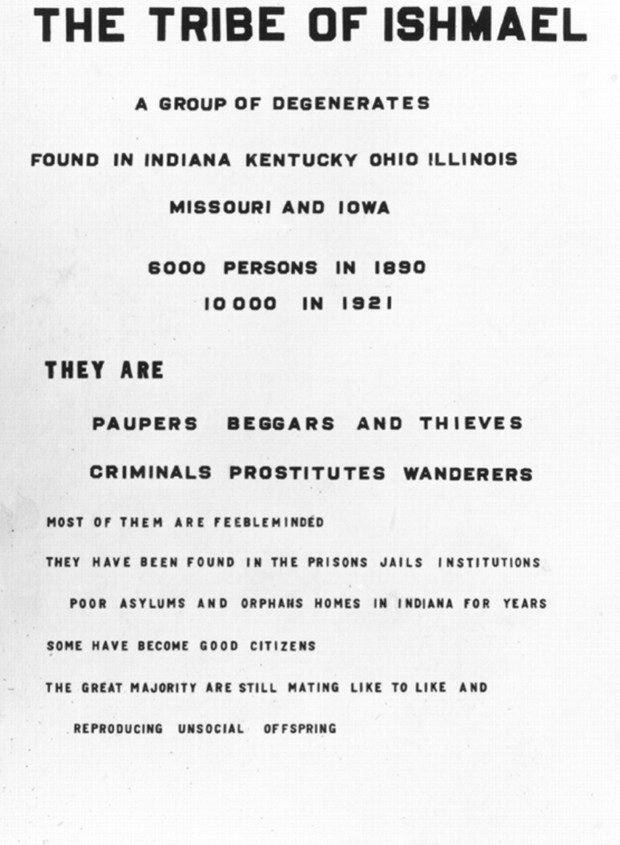

Figure 2.

American eugenicists believed that “degenerates” should not reproduce

From the collection of the American Philosophical Society

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen Vicchio for his reviews of previous drafts.

Competing interests: None declared

Authors: This work was completed when Hoangmai Pham was a Jay I Meltzer ethics fellow at Columbia University and was supported by the Vidda Foundation. Barron Lerner is an Angelica Berrie Gold Foundation fellow. Both authors received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The opinions expressed here are their own.

References

- 1.Reilly PR. The Surgical Solution: A History of Involuntary Sterilization in the United States. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991: 59-160.

- 2.42 CFR § 441. 201-206 (1990).

- 3.Krais WA. The incompetent developmentally disabled person's right of self-determination: right-to-die, sterilization, and institutionalization. Am J Law Med 1989;15: 333-361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trenckner TR. Annotation. In: Power of Parent to Have Mentally Defective Child Sterilized. American Law Reports. 3rd ed. 1976;74: 1224-1233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.New York City Charter. Administrative Code of the City of New York § 4: 17-401-17-408.

- 6.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF, eds. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994: 170-181.

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Sterilization of women who are mentally handicapped. Pediatrics 1990;85: 868-871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Ethics. Sterilization of Women Who Are Mentally Handicapped. ACOG Committee Opinion 63. Washington, DC: ACOG; 1988.

- 9.Lachance D. In re Grady: the mentally retarded individual's right to choose sterilization. Am J Law Med 1981;6: 559-590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salerno LJ, Park JK, Giannini MJ. Reproductive capacity of the mentally retarded. J Reprod Med 1975;14: 123-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bovicelli L, Orsini LF, Rizzo N, Montacuti V, Bacchetta M. Reproduction in Down syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 1982;59: S13-S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patterson-Keels L, Quint E, Brown D, Larson D, Elkins TE. Family views on sterilization for their mentally retarded children. J Reprod Med 1994;39: 701-706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott ES. Sterilization of mentally retarded persons: reproductive rights and family privacy. Duke Law J 1986;806: 815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.170 NJ Super Ct 98, 405 A.2d 851 (1979).

- 15.Newton JR. Sterilization. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 1984;11: 603-640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dardano KL, Burkman RT. The intrauterine contraceptive device: an often-forgotten and maligned method of contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;181: 1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]