Like many of their patients, physicians struggle to cope with chronic illness. While they have issues in common with other chronic disease patients, regardless of profession, physicians who are ill face an additional set of challenges. In this article, we address the following questions:

How common is chronic illness among physicians?

What are the additional challenges that physicians face in coping with chronic illnesses?

How can physicians cope better with chronic disease?

METHODS

Few studies have specifically addressed chronic disease in physicians. Our advice is based on our experience working with chronically ill physicians in a private psychiatric practice (M G) in which the entire patient group comprises physicians and through a careers advice resource and an online support service for physicians with chronic disease (R M).1

PREVALENCE OF CHRONIC DISEASE IN PHYSICIANS

Little information is available on the prevalence of chronic physical and mental illness in physicians either in North America or in the United Kingdom. Some US authors have suggested prevalence rates of 2.5% to 4%, but these rates apply only to physical disabilities and are only estimates without corroborating data.2,3 No prevalence study of chronic illness in physicians has been published, and most current information is anecdotal. The largest study of physical disability in physicians in the United States showed a wide range of different disabilities in this patient group, many of whom continued to practice medicine despite their limitations.4 No similar study has been conducted in the United Kingdom.

A chart review of 248 physician-patients in a psychiatric practice (M G) showed that 203 (82%) have a chronic mental illness (unpublished data). Of these, 61 (30%) have concomitant chronic physical illness. Only 12 (5%) have ever taken time off work for reasons related to this illness. This finding supports assumptions that the true prevalence of chronic illness in this population may be underreported, and it suggests that physicians often just “accept, adapt, and carry on,” or as is often the case, carry on and adapt before accepting their illness.

CHALLENGES FACING PHYSICIANS WITH ILLNESS

Common personality traits of physicians have been described in a handbook published by the American Psychiatric Association.5 Generally, physicians are perfectionists. They tend to have a strong sense of responsibility and a need for both control and approval. They often are plagued by self-doubts and tend to defer or delay gratification. All of these traits can affect the course of their chronic illness—the diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing management.

Physicians often delay getting help when they first notice symptoms of an illness. The reasons for such delay include not wanting to appear weak or as if they are overreacting. They may be concerned about being wrong in their self-diagnosis or may not want to “bother” colleagues. Some physicians may not think that self-care is a priority, perhaps assuming they will “get around to it later.”

The treatment of physician-patients may differ from that for other patients. Physician-patients often deny or minimize their symptoms, which may result in inadequate treatment. Physicians may find it difficult to care for a colleague or to explain things adequately to them. Physician-patients may want to take control of their own medication schedules—by self-medicating, changing medications or dosage, or discontinuing medications on their own.

Accepting that they have a chronic illness is often difficult for physicians, most of whom hold idealistic views of their role in treating illness and fighting disease. The discovery that they have a chronic illness may lead to grief as they mourn the loss of their own perfect health. They may be anxious about the outcome of the illness and have fears of being disabled to the extent that they are unable to function as a physician—a huge part of their identity. Some physician-patients react with anger, frustration, and protest at being unable to prevent or fix their illness. Others may feel the injustice of contracting a disease that they think they do not deserve. Guilt can arise when they acknowledge the added burden their illness places on their families at home and their colleagues at work, especially when no contingency coverage is provided in their practice or the inflexibility of their work schedule makes it hard to take time on short notice.

TIPS ON AVOIDING STRESS AND COPING WITH ILLNESS

With the awareness of their new limitations and inabilities and the resulting loss of self-esteem, physicians with chronic illness are at risk of depression. They feel powerless, and because this feeling is the key cause of stress, their focus should be directed to what they can actually control in the 3 key domains of their lives—personally, at work, and at home.

We have developed checklists to help physician-patients take more control in each of these areas. These activities become easier with practice and time.

Taking more control in your personal life

Find physicians that you trust, share your worries, and give them the responsibility for your care

Adhere as much as possible to the treatment regimen that is suggested

Try to accept the fact that you have a chronic illness

Enlist the help of a counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist if you are having trouble accepting or coping with your illness

Get regular sleep—it is restorative, will help you cope, and increases energy levels

Exercise regularly

Admit when you are angry so that you can then manage your negative feelings

Be kind and gentle with yourself, much as you would treat a patient or colleague

Set aside time to worry and to look for solutions to problems. Then, let go of the worrying until the next scheduled “worry time”

Look for and enjoy humor daily

Learn a relaxation technique and practice it regularly. Meditation, for example, has been shown to benefit chronic pain6 and may benefit other symptoms of chronic illness7

Reach out to family and friends and allow them to help and support you

Address your spiritual and religious needs to provide purpose, meaning, and values in life

Prepare yourself for challenging situations

Join or start a support group

Help someone else

Treat yourself to a new book, a facial, or a fascinating course

Remind yourself of the things you can do and do them

Be patient

Taking more control at work

Inform and educate your colleagues about your illness. Remind them that you are not choosing this illness and any inconvenience caused them when you are unavailable is not on purpose

Be prepared for questions from patients. Reassure them that you will be available to meet their needs and discuss backup arrangements that have been made in case you are ill

Be assertive of your special needs, such as your need for a specialized wheelchair, software, robotics, or hearing/visual aids

Modify your working hours and workload

Ensure that a system of coverage of duties is established should you need to go to a medical appointment or into the hospital for care

Consider specialties conducive to your abilities, such as psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, or medical research. This choice depends on your particular disability and interests

Take regular breaks and holidays

Taking more control at home

Reach out to family

Communicate your needs and how you are doing directly and clearly

Do not withdraw. Work on staying intimate—emotionally, physically, and sexually

CONCLUSION

Chronic illness is difficult to live with and to manage, especially for physicians who are expected to be caregivers and not “caretakers.” It is not easy to learn to accept care. Although the symptoms of a chronic disease do not disappear, no patient needs to suffer without seeking help. A comprehensive approach provides tools to allow physicians to continue to lead active and productive lives.

Table 1.

| Vignettes |

|---|

| A 50-year-old female physician awaits renal transplantation. She developed chronic renal failure requiring dialysis at age of 20 but decided to study medicine despite her chronic illness. She works part time in diabetes care, although she finds this difficult because she often identifies closely with her patients. Her fears of the planned transplantation are overwhelming because she knows all the details of what will happen. She becomes obsessed with the appearance of the scar, the likely prognosis, and the possible complications. She spends hours on the Internet daily seeking more information because she feels out of control. Through her searching, she finds a support group for patients waiting for kidney transplantation, which she finds helpful. After successful surgery, she learns to adapt to living with a transplant and to reassessing her ability and strength on a daily basis. |

| A 40-year-old male surgeon receives a diagnosis of macular degenerative disease. He decides to re-tain for a career in rehabilitation medicine because this specialty is compatible with his visual impairment. Despite increasing difficulties with his vision, he feels unable to ask for modifications at work. “My problems are not that bad,” he says. But eventually, he approaches his senior colleagues to apprise them of his situation. He then is able to modify his work environment, such as installing a special computer-magnifying device and having an assistant to read questions for patient assessments. |

Summary points

Documented information on chronic illness among physicians is limited; prevalence rates of physical disabilities of 2.5% to 4% have been suggested

Physicians often accept, carry on, and adapt to the chronic illness

Personality traits common to physicians can affect the course of the illness

Physicians with chronic illness are at risk for depression

Physicians coping with chronic illness should focus on what they can control in all the different domains of their lives

Resources

Organizations

Canadian Association of Physicians with Disabilities

Dr Ashok Muzumdar; 1 Meridian Pl, Ste 404 S, Ottawa, ON K2G 6N1; (613) 228-3096

This initiative is being set up to provide resources for physicians with physical disabilities.

American Society of Handicapped Physicians

3424 S Culpepper Ct, Springfield, MO 65804; (417) 881-1570

This general resource is for doctors or trainees with physical disabilities.

Online support

Chronic Diseases Matching Scheme

web.bma.org.uk/public/chill.nsf

This group allows doctors with chronic disease, worldwide, to support each other.

Additional reading

Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ. The Handbook of Physician Health. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000.

Swanson DW. Mayo Clinic on Chronic Pain. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. New York: Kensington Publishing Corp; 1999.

Corbet B, Madorsky JG. Physicians with disabilities. In: Rehabilitation Medicine—Adding Life to Years. West J Med 1991;154:514-521.

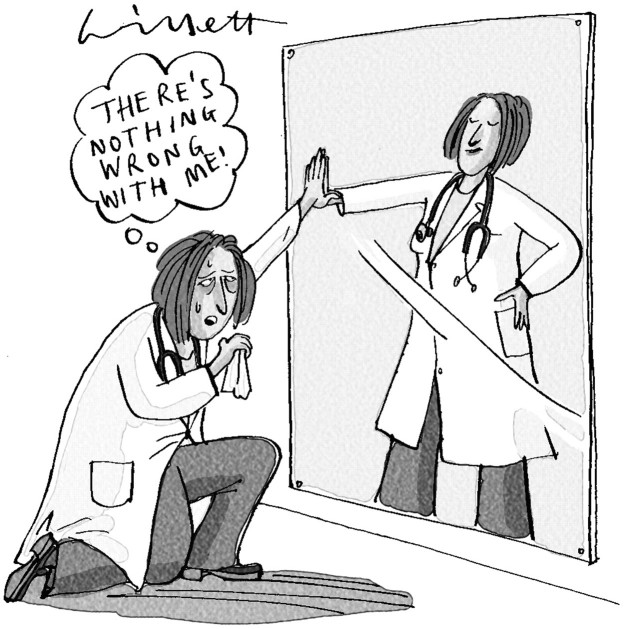

Figure 1.

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.MacDonald R. Career advice for doctors with a chronic illness. BMJ 2001;322: 1136-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis SB. The physically handicapped physician. In: Callan JP, ed. The Physician: A Professional Under Stress. East Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1983: 318-326.

- 3.Martini CJM. Physical disabilities and the study and practice of medicine. JAMA 1987;257: 2956-2957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wainapel SW. Physical disability among physicians: an analysis of 259 cases. Int Disabil Stud 1987;9: 138-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gautam M. Depression and anxiety. In: Goldman LS, Myers M, Dickstein LJ, eds. The Handbook of Physician Health. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2000: 80-94.

- 6.Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med 1985;8: 163-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. The Program of the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center; 1991.