Medical problems that previously carried considerable mortality risk can now be managed more effectively. As a result, chronic medical illnesses have become more prevalent in recent years. With the increase in life expectancy comes a set of psychological challenges that face the chronically ill.

Chronic disease is associated with high levels of uncertainty. Patients need to change their behavior as part of a new lifestyle of self-care. They also have to endure debilitating and demanding treatments. These are some of the factors that make adjustment to chronic medical illness psychologically demanding.

It is generally accepted that around a quarter of patients with chronic medical problems have clinically significant psychological symptoms. In some cases, these psychological symptoms themselves are associated with physical morbidity. For example, when medical factors are controlled for, the risk of myocardial infarction increases 4- to 5-fold as a result of the presence of depressive symptoms.1 Even in the absence of overt psychological or psychiatric disorder, patients have to regulate often-complex and ever-changing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

In this article, I outline how primary care physicians can incorporate some principles from cognitive therapy into their management of patients with chronic disease. Cognitive therapy is effective in managing chronic mental health problems2 and many of the long-term symptoms of chronic physical illnesses, including chronic pain.3,4

WHAT IS COGNITIVE THERAPY?

Two patients may have the same physical health problems, yet have markedly different psychological responses. For example, a man with multiple sclerosis who believes that his ability to make a useful contribution to life is finished is likely to experience depressed mood and avoidance of previously enjoyed activities. But a different man with the same condition who acknowledges that his life will have to change, but who believes that he will be able to discover new ways to make a contribution, is likely to make a better psychological adjustment to his illness.

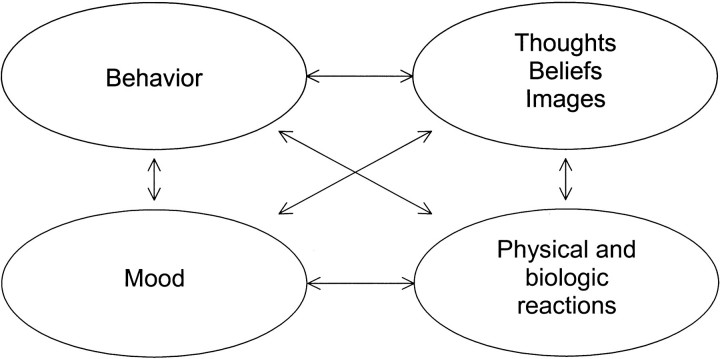

These differences in patient psychological responses can be understood by examining patients' thoughts about their illness. This is a fundamental principle behind cognitive therapy—a focused, structured, collaborative, and usually short-term psychological therapy that aims to facilitate problem solving and to modify dysfunctional thinking and behavior (figure).

Several factors make a cognitive therapy framework particularly suited to address the problems associated with chronic disease:

Chronic medical problems are often associated with the types of psychological problems for which cognitive therapy has proven efficacy, such as mood disorder and fatigue

The importance of adopting an active self-management approach and the need for patients to establish collaborative relationships with health care staff both lend themselves to the philosophy and central tenets of cognitive therapy

The emphasis on building a repertoire of skills for the management of psychological problems within cognitive therapy can be applied to promoting the acquisition of skills in chronic disease selfmanagement

The generic cognitive model outlines how the thoughts, behaviors, moods, and physical reactions that patients have each tend to contribute to the other components in the model. In other words, thinking “There is no point—nothing I do makes any difference” will not only contribute to sadness but also is likely to increase the avoidance of activities. This in turn will lower energy levels, which further depresses mood (and so on). There is a growing number of psychological disorders for which cognitive behavioral models and therapy protocols have been developed, many of which have been shown in research trials to be effective.

Cognitive therapy sessions are usually structured by a collaboratively agreed-on agenda. Active participation is encouraged by giving patients homework assignments to do between therapy sessions. Treatment involves the application of a range of cognitive and behavioral strategies designed to alter the factors that trigger, maintain, or exacerbate symptoms. The strategies are effective in helping patients to gain control over both psychological and physical symptoms.

A number of simple cognitive therapy techniques can be used by primary care physicians to care for their patients with chronic diseases—agenda setting, self-monitoring, experimentation, and changing distressing thoughts.

Table 1.

Example of self-monitoring in a patient with chronic pain

| M = medication | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R = relaxation | ||||

| Time | Activity | Depression, 0-10 | Pain, 0-10 | C = challenge thoughts |

| 9 AM | Getting dressed | 8 | 7 | M, C |

| 10 AM | Eating breakfast | 7 | 5 | |

| 11 AM | Walking dog | 4 | 5 | C |

| 12 noon | Phoning Michael | 3 | 4 | |

| 1 PM | Tidying basement | 8 | 8 | M, C |

Agenda setting

Patients with chronic medical problems have many physical, social, and psychological problems. Physicians do not always have time to address all of these within a single consultation. This fact, combined with the fact that some presenting problems have no apparent solution, can be overwhelming for physicians, who may not know where to start. Setting an agenda is one method for maximizing the chance that a consultation will make some progress toward solving a patient's problems. For example:

We have about 15 minutes today, and I want to make sure that we use the time we have to the best effect. The best way I have found to do this is to set an agenda that highlights the main things we want to talk about. Is there something that you particularly wanted to cover today?

Agenda setting reflects the collaborative stance of cognitive therapy in that both physician and patient can assign agenda items. This minimizes the risk that patients will disclose their main concern just as they are leaving the consulting room. When a series of appointments is being arranged, there may be a standing item that always appears on the agenda, such as symptom severity or the presence of side effects.

Self-monitoring

Cognitive therapy usually involves a series of tasks (“homework”) that are completed outside sessions and at various phases of therapy. During assessment, this often involves selfmonitoring in the form of diary keeping (see sample above). Examples of this might be recording mood fluctuations, discrete episodes of problem behavior, or the thoughts and images associated with a negative mood state. In a patient with a chronic illness, this approach need not be restricted to psychological symptoms; it could equally be focused on collecting data to inform medical management, such as keeping a diary of physical symptom severity. For example:

There are 168 hours in the week, and I am in contact with you for only part of 1 of them. It will be useful for you to keep a record of some aspects of your rheumatoid arthritis. Today we talked about how you find that your energy is particularly low at the moment. I think it might help me to help you if you could start maintaining a diary of how much energy you have at particular times during the day.

There are no limits to the range of monitoring assignments that might result from a session. For example, you might ask your patients to write about their thoughts and feelings about their illness, its effects, and its treatment; to compile a list of unanswered questions; to write down thoughts related to worries for the future; to rate the extent to which pain interferes with certain activities; or to count the number of times that a relative provides reassurance.

Patients who have medical problems with an uncertain cause may develop unhelpful and inaccurate beliefs that in turn influence their psychological adjustment (for example, the beliefs provoke anxiety states) and behavioral responses (they seek unconventional cures). Inviting them to write a brief account of their understanding of a particular condition may reveal inaccurate beliefs that require correction or thoughts that mediate psychosocial difficulties (or both). Inviting them to write an account might simply involve asking, “What do you think are the causes of your condition?” and “What factors make it better or worse, and how do you explain this?” An example of a belief that could easily be corrected is, “If I take too much medication, I will become immune to its effects.” Homework that includes writing in this way may prompt a discussion about improving the self-management of a patient's disease, or it might identify the need for information and support.

Experimentation

Patients often report psychological benefits from assignments that have a purely monitoring role. Indeed, some homework tasks can be assigned primarily as a therapeutic intervention.

If you suspect that a patient's symptoms are being triggered by a certain event, you could ask that patient to keep a symptom diary to note any triggers. For example, you might suspect that the patient's mood and adherence to medication vary according to the presence of family disagreements. You say to the patient that the monitoring is “an experiment.” This can be of particular benefit when you have differing views from your patient as to the precise trigger behind certain symptoms. In a spirit of collaboration, you first acknowledge that your views differ from the patient's before suggesting that the experiment can test out these differing views. For example:

I have been wondering if there is a link between the times that you take your medication and when you are feeling anxious. I know you don't think that there is a strong link (patient agrees). I may be wrong. It could be that there is no link at all. Or perhaps there is a link only some of the time. Will you consider keeping a diary to look at this in more detail? Can you note down the times that you take your medication and at the same time keep a rating of your anxiety? This way, we can check out which of our views is more accurate.

Changing distressing thoughts

Cognitive therapy usually involves the modification of thoughts and behaviors that seem to be contributing to a patient's symptoms. Clearly, the application of a simple strategy cannot change a major psychological disorder. However, the application of simple techniques based on cognitive therapy may alleviate some distress. An example of one such simple technique is when you verbally challenge a patient's distress-producing thoughts. For example:

Table 2.

| Questions that can help patients discover less-distressing alternative thoughts |

|---|

|

Resources

Published sources

Beck JS. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995.

Enright SJ. Cognitive behavior therapy — clinical applications. BMJ 1997;314:1811-1816.

Leahy R. Cognitive Therapy: Basic Principles and Applications. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1996.

Moorey S. When bad things happen to rational people: cognitive therapy in adverse circumstances. In: Salkovskis P, ed. Frontiers of Cognitive Therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996:450-469.

White CA. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Chronic Medical Problems: A Guide to Assessment and Treatment in Practice. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2001.

Online resources

Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research, Philadelphia. This is the site for the Institute founded by the “father of cognitive therapy,” Dr Aaron T Beck and his daughter, Dr Judith Beck. The Bookstore and Newsletter sections are essential ways to keep up to date with latest developments. Available at www.beckinstitute.org

American Institute for Cognitive Therapy, New York. This site has links to helpful fact sheets and a section on commonly asked questions. Available at www.cognitivetherapynyc.com

Center for Cognitive Therapy, Huntington Beach, CA. Dr Padesky, one of the authors of a best-selling cognitive therapy treatment manual (see list of references) is based at this center. This site has a useful section on ordering top-quality audiovisual materials for cognitive therapy training. Available at www.padesky.com

British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies. This site includes a searchable database of UK-accredited cognitive behavioral therapists, conference information, and leaflets on a range of topics (including “Chronic Pain” and “General Health Problems”). Available at www.babcp.org.uk

New York Institute for Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies. This site includes a section that provides a full explanation of the background and principles behind cognitive therapy. Available at www.cognitivetherapy.com

Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. A useful source of information for upcoming events and publications relating to psychological aspects of physical health. Available at www.health-psych.org

When you are feeling distressed, it can help to stop and think about what thoughts are passing through your mind. This way, you get to see what thoughts are feeding your distress. You can write these down and then start to challenge them as a way of gaining some control. Challenges are easier to come up with if you think of your own responses to questions like, “If someone I loved thought this, what would I advise them?” or “When I am less distressed, how would I tend to think about this?” Sometimes it helps to simply write down a less-distressing alternative.

Most cognitive therapy self-help manuals provide further information on this strategy of verbally challenging thoughts (and on a range of other treatment strategies) (see next box). In some clinical situations, it may be appropriate to complement medical management with the use of a structured patient manual that patients can use to work through problems between consultations.5,6

REFERRING A PATIENT FOR COGNITIVE THERAPY

Patients with psychological problems related to their chronic medical illness may benefit from referral for cognitive therapy. Patients most likely to benefit from cognitive therapy are those who are able to identify and differentiate emotions and behaviors, accept that they have some responsibility toward addressing their problems, and accept the application of a cognitive theory approach to their problems and situation.

When physicians decide that a patient is presenting with problems for which cognitive therapy is indicated, it is important that they refer the patient to a suitably qualified and skilled clinician. The Academy of Cognitive Therapy is responsible for the certification of clinicians skilled in cognitive therapy. Certification is awarded to those individuals who, based on an objective evaluation, have demonstrated an advanced level of expertise in cognitive therapy. The academy includes physicians, psychologists, social workers, and other mental health professionals from around the world. Details on certified cognitive therapists can be found at the academy's web site (www.academyofct.org).

CONCLUSIONS

Management of the psychological aspects of living with a chronic medical illness can challenge physicians and patients. Cognitive therapy has proven efficacy in the management of common emotional and psychological disorders, and cognitive therapy techniques can be used to manage chronic disease in a problem-focused and psychologically sensitive manner.

Summary points

Adjustment to chronic medical illness can be psychologically demanding

Different patients adjust in different ways through their own thoughts and interpretations about themselves, the world, and their illness

Primary care physicians can use cognitive therapy techniques to manage patients with chronic disease in a more structured, problem-focused, and psychologically sensitive way

Some patients with chronic disease will develop psychological disorders that require referral to a specialist for cognitive therapy

Figure 1.

Generic cognitive behavioral model illustrating the links between mood, behavior, thoughts, and physical reactions (based on Greenberger D, Padeksy C.5 Reproduced with permission.)

Figure 2.

Stoic philosopher Epictetus (ca 55-ca 135 CE), considered the father of cognitive behavior, wrote: “men are disturbed not by things but by the views they take of them.”

Competing interests: None declared

Author: Craig White is cancer research campaign fellow in Psychosocial Oncology at the Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland. He is author of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Chronic Medical Problems and a founding fellow of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy.

References

- 1.Hippisley-Cox J, Fielding K, Pringle M. Depression as a risk factor for ischaemic heart disease in men: population based case-control study. BMJ 1998;316: 1714-1719 [erratum published in BMJ 1998;317:185]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeRubeis RJ, Crits-Christoph P. Empirically supported individual and group psychological treatments for adult mental disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 1998;66: 37-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greer S, Moorey S, Baruch JDR, et al. Adjuvant psychological therapy for patients with cancer: a prospective randomised trial. BMJ 1992;304: 675-680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain 1999;80: 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenberger D, Padeksy C. Mind Over Mood: Changing How You Feel by Changing the Way You Think. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1996.

- 6.Williams CJ. Overcoming Depression. London: Arnold; 2001.