Abstract

The Antarctic whitefin plunderfish Pogonophryne albipinna belongs to the family Artedidraconidae, a key component of Antarctic benthic ecosystems within the order Perciformes and the suborder Notothenioidei. While genome research on P. albipinna using short-read sequencing is available, high-quality genome assembly and annotation employing long-read sequencing have yet to be performed. This study presents a chromosome-scale genome assembly and annotation for P. albipinna, utilizing a combination of Illumina short-read, PacBio long-read, and Hi-C sequencing technologies. The resulting genome assembly spans approximately 1.07 Gb, with a longest scaffold measuring 59.39 Mb and an N50 length of 41.76 Mb. Of the 1,111 Hi-C scaffolds, 23 exceeded 10 Mb and were thus classified as chromosome-level. BUSCO completeness was assessed at 95.6%. The assembled genome comprises 50.68% repeat sequences, and a total of 31,128 protein-coding genes were predicted. This study will enhance our understanding of the genomic characteristics of cryonotothenioids and facilitate comparative analyses of their adaptation and evolution in extreme environments.

Subject terms: Genome evolution, Eukaryote

Background & Summary

The Artedidraconidae family, part of the suborder Notothenioidei within the order Perciformes, plays a significant role in Antarctic benthic ecosystems. It accounts for a substantial portion of fish species diversity in the high Antarctic Zone, Weddell Sea, and Ross Sea1–5. Comprising four genera—Artedidraco, Dolloidraco, Histiodraco, and Pogonophryne—Artedidraconids feature a mental barbel with species-specific morphology6–12. Traditional taxonomy identifies 27 species within the genus Pogonophryne, the most diverse among Antarctic notothenioids13. However, recent research suggests that this species diversity may be overestimated14,15. Specifically, Parker et al.14 proposed condensing the majority of Pogonophryne species into five (or six, if new species are included) based on comprehensive analyses of phylogenomic data and morphological traits. Eastman and Eakin15 further organized the 27 Pogonophryne species into five groups within three categories: the P. albipinna group (unspotted), and the P. barsukovi, P. marmorata, P. mentella groups (dorsally spotted), as well as the P. scotti group (dorsally unspotted).

Among these, P. albipinna, also known as the whitefin plunderfish, is a representative species of the P. albipinna group. It is distinguished not only by a lack of dark spots on its head and trunk but also by its predominantly white fins and its habitat in water depths exceeding 1,500 meters10,15–17. Although genome studies on P. albipinna have been published, such as a complete mitochondrial genome report18 and a preliminary genome survey19, research employing state-of-the-art technologies for high-quality genome assembly and gene annotation has not been conducted. Furthermore, while the chromosome number for other Pogonophryne species, such as P. barsukovi, P. marmorata, P. mentella, and P. scotti, has been established through cytogenetic studies as 2n = 4620,21, the chromosome number for P. albipinna remains unidentified.

Recent research has focused on the genomic characteristics of Antarctic fish species, revealing whole genome sequence and assembly data. These studies also provide genomic insights into adaptations to low-temperature environments, including genes associated with freeze resistance, oxygen-binding, and oxidative stress22–29. The genus Pogonophryne is hypothesized to exhibit specific features for cold-water adaptation, such as functional alterations in hemoglobin or the presence of antifreeze glycoprotein (AFGP). For example, P. favosa possesses a specialized structure, convexitas superaxillaris, located beneath the base of the pectoral fin, which secretes antifreeze proteins30. In a separate study, the amino acid sequences and ligand-binding properties of hemoglobin were examined in two species of Artedidraconidae (Artedidraco orianae and P. scotti). These species demonstrated unexpectedly high oxygen affinity, contrasting with the hemoglobin deficiency observed in channichthyid icefish31.

In this study, we performed a chromosome-level genome assembly and annotation of P. albipinna, utilizing PacBio long-read sequencing and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) technology. This work aims to elucidate the genomic characteristics of Antarctic fish and may serve as a basis for further investigations into their adaptation and evolutionary responses to extreme environments.

Methods

Sampling and DNA extraction

Samples of P. albipinna were collected from the Ross Sea, Antarctica (77°05′S, 170°30′E in CCAMLR Subarea 88.1) and subsequently transported to the Korea Polar Research Institute (KOPRI) in a frozen state. Muscle tissues were excised from these frozen specimens for the extraction of high molecular weight (HMW) DNA using a conventional phenol/chloroform-based method. Molecular identification of the species was carried out using a primer set (FishF2 and FishR2) specifically designed to amplify the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene region32.

Long-read sequencing and assembly

The extracted HMW DNA was utilized to construct 20 kb size-selected PacBio Sequel libraries, following the manufacturer’s protocol and employing the BluePippin size-selection system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, USA). Specifically, the SMRTbell library was prepared using the SMRTbell Template Prep Kit 1.0, and the SMRTbell-polymerase complex was generated using the Sequel Binding Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). This complex was then loaded into SMRT cells 1 M v3 and sequenced with the Sequel Sequencing Kit 3.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) for a 600-min movie time per cell. The genome of P. albipinna was sequenced using six PacBio SMRT cells, generating 7,776,779 raw reads with a total bases of approximately 81.11 Gb (Table 1). De novo genome assembly was performed using FALCON-Unzip assembler v0.433, with parameter settings of length_cutoff = 12,000 and length_cutoff_pr = 10,000. Subsequently, the draft genome assembly was polished using Pilon v1.2334 to enhance its accuracy; this utilized a BAM file generated by BWA-MEM35 based on short-read sequencing data obtained in a prior genome survey19. Lastly, Purge Haplotigs36 was employed to identify and deduplicate haplotigs in the assembled genome.

Table 1.

Sequencing data generated for Pogonophryne albipinna genome assembly and annotation.

| Library type | Platform | Number of cells | Number of reads | Total read length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-reads | PacBio Sequel | 6 | 7,776,779 | 81,108,670,479 |

| Hi-C | Illumina Novaseq | 733,064,394 | 110,692,723,494 | |

| Iso-seq | PacBio Sequel | 2 | 37,596,041 | 62,649,769,489 |

Hi-C sequencing and chromosome scaffolding

Muscle tissue was frozen and ground in liquid nitrogen for the construction of the Dovetail™ Hi-C library, following the instructions in the Dovetail™ Hi-C kit manual (Dovetail Genomics, Scotts Valley, CA, USA). Sequencing of the Hi-C library was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq. 6000 platform with a 2 × 150 bp paired-end run configuration. A total of 733,064,394 Hi-C reads, with an aggregate length of approximately 110.69 Gb (Table 1), were aligned to the draft genome assembly using Juicer v1.5.737. Subsequently, a candidate assembly was produced using the 3D de novo assembly (3D-DNA) pipeline38. This candidate assembly underwent manual review, modification, and visualization via Juicebox v1.539 to finalize both the genome assembly and the Hi-C contact map.

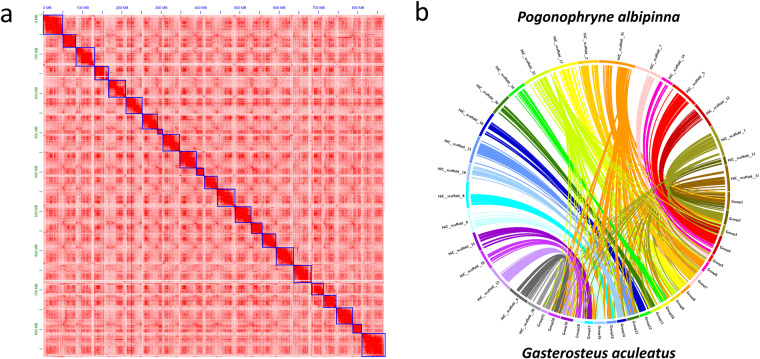

Our finalized genome assembly measured approximately 1.07 Gb with a maximum scaffold length of 59.39 Mb. We identified 1,111 Hi-C scaffolds, 23 of which exceeded 10 Mb in length, ranging between 13.61 Mb and 59.39 Mb (Table 2 and Table 3). These 23 pseudo-chromosomes in the P. albipinna genome aligned well with the 21 chromosomes of the G. aculeatus genome (Fig. 1). Notably, chromosomes from Group 1 and Group 4 of G. aculeatus corresponded to two chromosomes in P. albipinna each (HiC_scaffold_11 + 27 and HiC_scaffold_5 + 14). Karyotype studies have indicated that four out of the five species groups in the Pogonophryne genus possess 23 chromosome pairs20,21. This study was the first to identify these 23 scaffolds as chromosomes in P. albipinna, affirming that all groups within the Pogonophryne genus have a chromosomal count of 2n = 46.

Table 2.

Statistics for Pogonophryne albipinna genome assembly.

| Assembly | Hi-C |

|---|---|

| Number of scaffolds | 1,111 |

| Total size of scaffolds (bp) | 1,074,502,020 |

| Longest scaffold (bp) | 59,391,674 |

| N50 scaffold length (bp) | 41,761,029 |

| Number of scaffolds >10 Mb | 23 |

Table 3.

Lengths of Pogonophryne albipinna genome scaffolds (over 10 Mb).

| No. | Scaffold name | Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chromosome_1 | 59,391,674 |

| 2 | Chromosome_2 | 50,992,350 |

| 3 | Chromosome_3 | 47,603,259 |

| 4 | Chromosome_4 | 45,138,401 |

| 5 | Chromosome_5 | 45,007,767 |

| 6 | Chromosome_6 | 44,948,606 |

| 7 | Chromosome_7 | 43,946,785 |

| 8 | Chromosome_8 | 42,676,725 |

| 9 | Chromosome_9 | 42,586,816 |

| 10 | Chromosome_10 | 42,495,260 |

| 11 | Chromosome_11 | 42,083,915 |

| 12 | Chromosome_12 | 41,761,029 |

| 13 | Chromosome_13 | 38,342,872 |

| 14 | Chromosome_14 | 35,488,582 |

| 15 | Chromosome_15 | 34,847,635 |

| 16 | Chromosome_16 | 32,696,055 |

| 17 | Chromosome_17 | 32,119,369 |

| 18 | Chromosome_18 | 31,599,154 |

| 19 | Chromosome_19 | 31,055,242 |

| 20 | Chromosome_20 | 27,672,119 |

| 21 | Chromosome_21 | 23,292,495 |

| 22 | Chromosome_22 | 19,419,747 |

| 23 | Chromosome_23 | 13,606,197 |

Fig. 1.

Chromosome-level genome assembly of Pogonophryne albipinna. (a) Hi-C interaction heat map for P. albipinna. The blue boxes represent the chromosomes. (b) Collinear relationship between P. albipinna and Gasterosteus aculeatus. Connections within the circle represent alignments between the two assemblies.

Transcriptome sequencing

RNA was extracted from muscle tissue using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. Owing to the quality constraints of the RNA, different specimens were used for DNA and RNA isolation. For Iso-seq library construction, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using a SMARTer PCR cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The SMRTbell library was then prepared as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was conducted on a Sequel system (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) using two SMRT cells 1 M v3 LR and Sequel sequencing chemistry 3.0. Iso-seq produced 37,596,041 subreads with a total of 62.65 Gb of nucleotides (Table 1). Analysis of Iso-seq data was performed using the Iso-seq 3 pipeline in SMRT Link v6.0.0 with default settings.

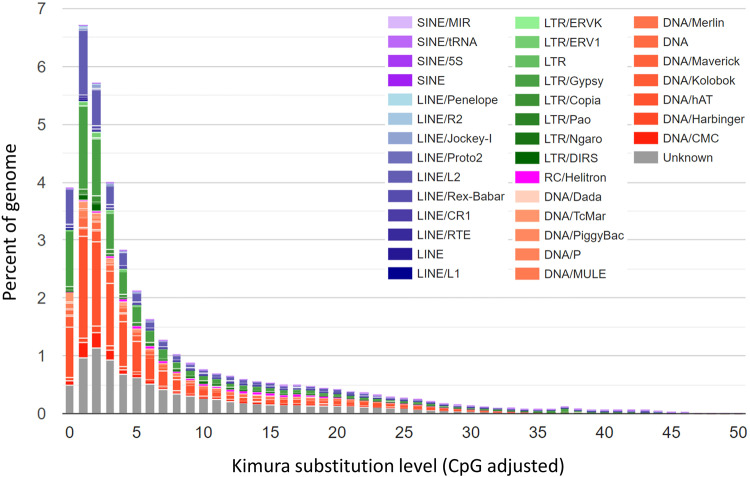

Repeat analysis and masking

A de novo repeat library was generated using RepeatModeler v1.0.340, incorporating the utilities RECON v1.0841, RepeatScout v1.0.542 and Tandem Repeats Finder v4.0943, all of which operated with default parameters. All repeats identified by RepeatModeler, except for transposons, were cross-referenced with the UniProt/SwissProt database44. To specifically identify long terminal repeat retrotransposons (LTR-RTs), LTR_retriever was executed45, utilizing raw LTR data sourced from LTRharvest46 and LTR_FINDER47. The assembled repeat library was then utilized to mask repetitive elements via RepeatMasker v4.0.9, accessed on November 24, 2020, from https://www.repeatmasker.org/. Analysis revealed that the P. albipinna genome comprises 50.68% repetitive sequences, of which 48.03% were transposable elements (TEs), including short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs, 0.29%), long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, 5.50%), long terminal repeats (LTRs, 17.91%), and DNA transposons (15.38%) (Table 4). Kimura divergence values for each alignment were calculated, and the interspersed repeat landscape was plotted using the scripts “calcDivergenceFromAlign.pl” and “createRepeatLandscape.pl”. The Kimura distances for all TE copies indicated that the P. albipinna genome harbored a greater number of recent TE copies with Kimura divergence K-values ≤ 5, primarily influenced by Gypsy LTR and hAT DNA elements (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Statistics for annotated Pogonophryne albipinna transposable elements.

| Class | Number of elements | Length occupied (bp) | Percentage of sequence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SINEs: | 20,523 | 3,063,718 | 0.29% |

| MIRs | 13,231 | 2,031,457 | 0.19% |

| LINEs: | 174,171 | 59,316,996 | 5.50% |

| LINE1 | 4,887 | 1,339,549 | 0.12% |

| LINE2 | 110,647 | 43,014,081 | 4.00% |

| LTR elements: | 471,673 | 192,373,177 | 17.91% |

| Gypsy | 138,972 | 60,560,082 | 5.64% |

| DIRSs | 10,542 | 6,693,107 | 0.62% |

| RC: Helitrons | 10,174 | 5,687,850 | 0.53% |

| DNA elements: | 531,943 | 165,424,411 | 15.38% |

| hAT-Ac | 141,912 | 43,112,186 | 4.01% |

| Unclassified: | 431,689 | 90,165,374 | 8.39% |

| Total interspersed repeats: | 1,640,173 | 516,031,526 | 48.03% |

| Low complexity: | 24,782 | 1,477,563 | 0.14% |

| Satellites: | 11,185 | 2,123,109 | 0.20% |

| Simple repeats: | 277,977 | 24,329,247 | 2.26% |

| Ribosomal RNAs: | 286 | 30,590 | 0.00% |

| Small nuclear RNAs: | 511 | 169,931 | 0.02% |

| Transfer RNAs: | 1,822 | 389,123 | 0.04% |

| Total bases masked: | 1,956,736 | 544,551,089 | 50.68% |

Fig. 2.

Kimura distance-based copy divergence analysis of transposable elements in teleost genomes. The graphs depict genome coverage (Y-axis) for each type of TE in the Pogonophryne albipinna genome.

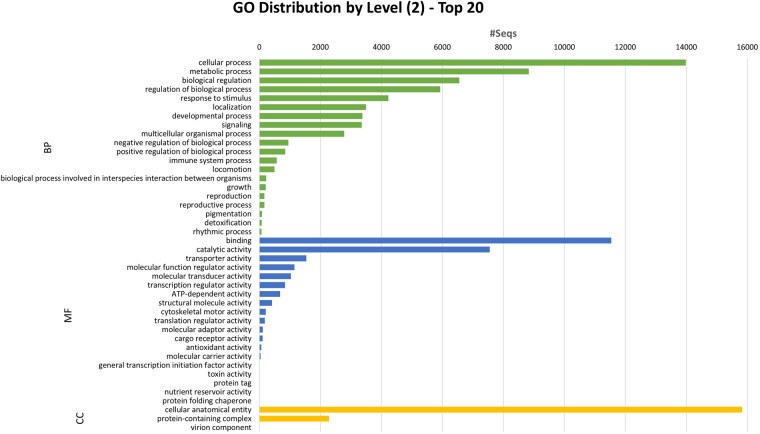

Gene prediction and functional annotation

Gene structure annotation was conducted using EVidenceModeler (EVM) v1.1.148, integrating multiple types of evidence for gene prediction. Initially, the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments (PASA) pipeline v2.5.149 was applied to Iso-seq data to generate transcript evidence. Ab initio gene prediction on the repeat-masked genome assembly was then performed using GeneMark-ES v4.6850. Protein hints were generated using Actinopterygii protein sequences from the SwissProt database44 using ProtHint v2.6.051. These hints were employed to produce protein-based evidence via GeneMark-EP+ v4.6851 and for ab initio gene prediction with Augustus v3.4.052. EVM combined all gene models, assigning weight values to each type of evidence (ABINITIO_PREDICTION, 1; PROTEIN, 50; TRANSCRIPT, 50) to produce a consensus gene structure. The consensus gene prediction was further refined using the PASA pipeline49 to include untranslated regions (UTRs) and alternatively spliced isoforms, based on Iso-seq data. In the P. albipinna genome assembly, EVM pipeline predicted a total of 31,128 protein-coding genes (Table 5). The cumulative lengths of exons and coding sequences were 48.20 Mb and 43.33 Mb, respectively, averaging 8.46 exons per gene (Table 5). Functional annotation of the predicted genes was performed by aligning them to the NCBI non-redundant protein (nr) database53 using BLASTP v2.9.054, with an e-value cutoff set at 1e-5. Protein functions were predicted using InterProScan v5.44.7955 on the translated protein sequences from the transcripts. Gene Ontology (GO) terms were assigned to the sequences using the Blast2GO56 module in OmicsBox v1.3.1157. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation was accomplished using the KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS)58 and KEGG Mapper59. Trinotate v3.2.060 provided a comprehensive functional annotation of the transcriptome sequences. Specifically, coding regions were identified using TransDecoder v5.5.0, followed by sequence homology searches using BLAST54 against the UniProt/SwissProt database44. Protein domain identification was performed using HMMER61 via the Pfam database62, while protein signal peptides were predicted with SignalP v5.063 and transmembrane domains with TMHMM v2.064. Consequently, 30,992 genes (99.56%) were annotated in at least one database (Table 5). Among these, 26,292 genes (84.5%) received annotations in the GO database (Table 5), and the distribution of GO terms is presented in Fig. 3.

Table 5.

Statistics for Pogonophryne albipinna genome annotation.

| Count | Length Sum (bp) | |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation database | Annotated number | Percentage (%) |

| Exon | 263,211 | 48,199,293 |

| CDS | 261,649 | 43,329,592 |

| No. Genes | 31,128 | |

| nr | 30,784 | 98.9 |

| GO | 26,292 | 84.5 |

| KEGG | 15,939 | 51.2 |

| SwissProt blastx | 25,041 | 80.4 |

| SwissProt blastp | 24,616 | 79.1 |

| Pfam | 22,314 | 71.7 |

| SignalP | 28,617 | 91.9 |

| TmHMM | 8,504 | 27.3 |

| InterProScan | 29,121 | 93.6 |

Fig. 3.

Gene ontology (GO) annotations of the predicted genes in the Pogonophryne albipinna genome. The horizontal axis indicates the number of genes in each class, while the vertical axis indicates the classes in the 2-level GO-annotation.

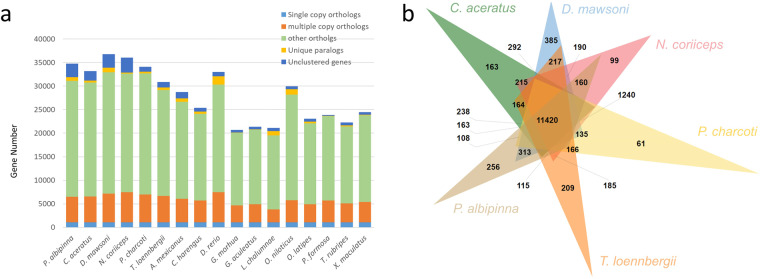

Gene family identification and phylogenetic analysis

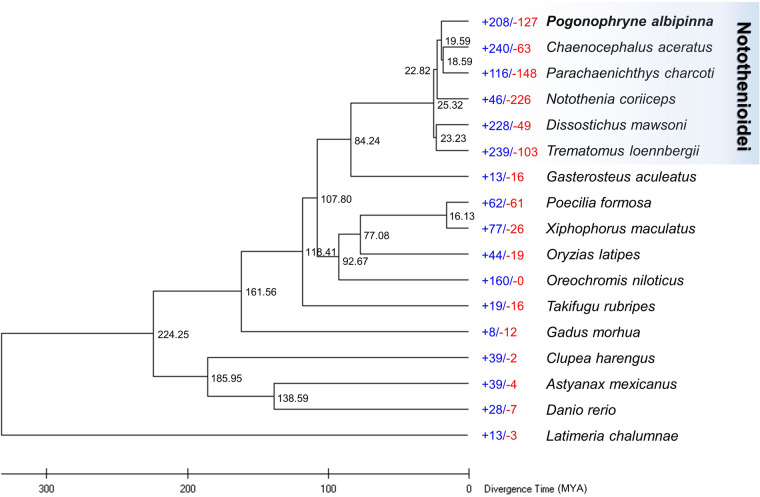

Protein sequences from sixteen teleost species were obtained, with only the longest transcript variant of each gene being selected for further analysis (Table S1). Orthogroups for 17 teleost species were determined based on protein sequence similarity using OrthoFinder v2.4.065 with default parameters. The analysis revealed that 6,727 orthogroups were shared across all 17 species, while 186 orthogroups, encompassing 766 genes, were specific to P. albipinna (Fig. 4a, Table S2). A maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was constructed using the concatenated protein sequences of 1,092 single-copy orthologous genes common to the 17 teleost species, employing MEGA X software66. Divergence times were estimated using TimeTree67, with median estimates for Gadus morhua and Danio rerio set at 224 million years ago. In the resulting tree, P. albipinna clustered with five other Antarctic fish species, diverging from a common ancestor with G. aculeatus approximately 84.24 million years ago (Fig. 5). The divergence time between P. albipinna and N. coriiceps was estimated to be around 22.82 million years ago, followed by a separation from the C. aceratus/P. charcoti clade about 19.59 million years ago (Fig. 5). Gene family expansions and contractions were analyzed using CAFE v4.2.168, with the parameters -p 0.05 and -filter. The analysis revealed that the P. albipinna genome had 208 significantly expanded and 127 significantly contracted gene families (Fig. 5). Expanded gene families in P. albipinna were enriched in telomere-related biological process GO terms (Table S3). GO enrichment analysis results for genes in expanded, contracted, and P. albipinna-specific gene families are presented in Tables S3–5. Comparative analysis of orthologous gene clusters among six Antarctic fish species (P. albipinna, C. aceratus, D. mawsoni, N. coriiceps, P. charcoti, and T. loennbergii) was conducted and visualized using OrthoVenn369. In these analyses, 11,420 orthologous gene families were commonly identified among the six Antarctic species, while 256 gene families were unique to the P. albipinna genome (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Gene family comparison. (a) Orthologous gene families between Pogonophryne albipinna and other fish species. (b) Venn diagram showing orthologous gene families among P. albipinna and five other Antarctic fish species.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of Pogonophryne albipinna within the teleost lineage and analysis of gene family gains and losses, including the number of gained gene families (+) and lost gene families (−). Each branch site number indicates divergence times between lineages.

Data Records

The final genome assembly of Pogonophryne albipinna has been deposited in GenBank with the accession number JAPTMU00000000070. The PacBio (SRR26989350), Hi-C (SRR26989351), and Iso-seq (SRR26989352) reads have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under study accession number of SRP30445471.

Technical Validation

Quality control of nucleic acids and libraries

The quality and quantity of the extracted DNA were assessed using a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a Fragment Analyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The main peak of the input genomic DNA was 28 kb and the final size of the SMRTbell library for long-read sequencing was ~24 kb. The size distribution of Hi-C fragments was centered around 200 bp and the final size-selected Hi-C library was distributed a size range of 200 bp to 1 kb. The RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, CA, USA), respectively. The RNA integrity number (RIN) value of the total RNA was 8.8 and the average library size for Iso-seq was ~2,800 bp.

Evaluation of genome assembly and annotation

To evaluate the assembly’s completeness, we used Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) v4.1.272 in genome assessment mode, employing the Actinopterygii_odb10 dataset. The assembly showed 95.6% (3,479) complete and 1.2% (42) fragmented genes among 3,640 Actinopterygii single-copy orthologs (Table 6). Additionally, BUSCO v4.1.272 in transcriptome assessment mode represented 85.4% (3,109) of completed and 3.1% (112) of fragmented BUSCOs in actinopterygii_odb10 dataset. The assembly’s contiguity was assessed using the N50 value, defined as the length of the shortest contig or scaffold constituting 50% of the total genome length. The N50 value for the P. albipinna genome assembly was 41.76 Mb (Table 2). Quality value (QV) and k-mer completeness were estimated using Merqury v1.373, resulting in a QV of 39.15 and completeness of 93.48% (Table 7). These metrics indicate high base-level accuracy and completeness for the assembly.

Table 6.

Completeness of the Pogonophryne albipinna genome assembly and annotation evaluated with Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO).

| Actinopterygii_odb10 | Genome | Transcriptome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage (%) | Number | Percentage (%) | |

| Complete BUSCOs (C) | 3,479 | 95.6 | 3,109 | 85.4 |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 3,407 | 93.6 | 2,924 | 80.3 |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 72 | 2.0 | 185 | 5.1 |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 42 | 1.2 | 112 | 3.1 |

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 119 | 3.2 | 419 | 11.5 |

| Total BUSCO groups searched | 3,640 | 3,640 | ||

Table 7.

Assembly validation of Pogonophryne albipinna genome using Merqury.

| Quality value (QV) | k-mer error rate | k-mer completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 39.15 | 1.22E-04 | 93.48 |

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research received support from the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST) grant funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries (KIMST 20220547), the National Institute of Fisheries Science (NIFS; R2023003), and a grant from Korea University.

Author contributions

H.P. and J.-H.K. designed the study. E.J., S.C., S.J.L., J.K., E.K.C., M.C., J.K., S.C. and J.L. carried out genome sequencing and assembly. E.J. and S.C. drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in manuscript writing and editing, as well as in compiling the supplementary information and preparing the figures.

Code availability

All bioinformatic software and pipeline used in this study were implemented according to the protocols provided by the software developers. The versions and parameters for each software can be found in the Methods section. Unless otherwise stated, default parameters were employed.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Euna Jo, Soyun Choi.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-023-02811-x.

References

- 1.La Mesa M, Cattaneo-Vietti R, Vacchi M. Species composition and distribution of the Antarctic plunderfishes (Pisces, Artedidraconidae) from the Ross Sea off Victoria Land. Deep Sea Res. II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2006;53:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2006.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olaso I, Rauschert M, De Broyer C. Trophic ecology of the family Artedidraconidae (Pisces: Osteichthyes) and its impact on the eastern Weddell Sea benthic system. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2000;194:143–158. doi: 10.3354/meps194143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eastman JT, Hubold G. The fish fauna of the Ross Sea, Antarctica. Antarct. Sci. 1999;11:293–304. doi: 10.1017/S0954102099000383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kock, K.-H. Antarctic fish and fisheries. (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

- 5.Hubold, G. Ecology of Weddell Sea fishes. Ber. Polarforsch. 103 (1992).

- 6.Hureau, J. C. Vol. 2 (eds Fischer, W. & Hureau, J. C.) Ch. Artedidraconidae, 245–251 (FAO, 1985).

- 7.Eastman JT, Eakin RR. Fishes of the genus Artedidraco (Pisces, Artedidraconidae) from the Ross Sea, Antarctica, with the description of a new species and a colour morph. Antarct. Sci. 1999;11:13–22. doi: 10.1017/S0954102099000036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eakin RR, Eastman JT, Jones CD. Mental barbel variation in Pogonophryne scotti Regan (Pisces: Perciformes: Artedidraconidae) Antarct. Sci. 2001;13:363–370. doi: 10.1017/S0954102001000517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombarte A, Olaso I, Bozzano A. Ecomorphological trends in the Artedidraconidae (Pisces: Perciformes: Notothenioidei) of the Weddell Sea. Antarct. Sci. 2003;15:211–218. doi: 10.1017/S0954102003001196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eakin, R. in Fishes of the Southern Ocean (eds Gon, O. & Heemstra, P. C.) 332–356 (JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology, 1990).

- 11.Eastman JT. Evolution and diversification of Antarctic notothenioid fishes. Am. Zool. 1991;31:93–110. doi: 10.1093/icb/31.1.93. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balushkin A, Eakin R. A new toad plunderfish Pogonophryne fusca sp. nova (Fam. Artedidraconidae: Notothenioidei) with notes on species composition and species groups in the genus Pogonophryne Regan. J. Ichthyol. 1998;38:574–579. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eastman JT, Eakin RR. Checklist of the species of notothenioid fishes. Antarct. Sci. 2021;33:273–280. doi: 10.1017/S0954102020000632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker E, Dornburg A, Struthers CD, Jones CD, Near TJ. Phylogenomic species delimitation dramatically reduces species diversity in an Antarctic adaptive radiation. Syst. Biol. 2022;71:58–77. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syab057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eastman JT, Eakin RR. Decomplicating and identifying species in the radiation of the Antarctic fish genus Pogonophryne (Artedidraconidae) Polar Biol. 2022;45:825–832. doi: 10.1007/s00300-022-03034-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eastman JT. Bathymetric distributions of notothenioid fishes. Polar Biol. 2017;40:2077–2095. doi: 10.1007/s00300-017-2128-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller, R. G. History and atlas of the fishes of the Antarctic Ocean. (Foresta Institute for Ocean and Mountain Studies, 1993).

- 18.Tabassum N, et al. Characterization of complete mitochondrial genome of Pogonophryne albipinna (Perciformes: Artedidraconidae) Mitochondrial DNA B: Resour. 2020;5:156–157. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1698361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jo, E. et al. Genome survey and microsatellite motif identification of Pogonophryne albipinna. Biosci. Rep. 41 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Morescalchi A, Morescalchi M, Odierna G, Sitingo V, Capriglione T. Karyotype and genome size of zoarcids and notothenioids (Taleostei, Perciformes) from the Ross Sea: cytotaxonomic implications. Polar Biol. 1996;16:559–564. doi: 10.1007/BF02329052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozouf-Costaz C, Hureau J, Beaunier M. Chromosome studies on fish of the suborder Notothenioidei collected in the Weddell Sea during EPOS 3 cruise. Cybium. 1991;15:271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn D-H, et al. Draft genome of the Antarctic dragonfish, Parachaenichthys charcoti. Gigascience. 2017;6:gix060. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SJ, et al. Chromosomal assembly of the Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni) genome using third-generation DNA sequencing and Hi-C technology. Zool. Res. 2021;42:124. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, et al. The genomic basis for colonizing the freezing Southern Ocean revealed by Antarctic toothfish and Patagonian robalo genomes. GigaScience. 2019;8:giz016. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giz016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim B-M, et al. Antarctic blackfin icefish genome reveals adaptations to extreme environments. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:469–478. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0812-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin SC, et al. The genome sequence of the Antarctic bullhead notothen reveals evolutionary adaptations to a cold environment. Genome Biol. 2014;15:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0468-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jo E, et al. Chromosomal-Level Assembly of Antarctic Scaly Rockcod, Trematomus loennbergii Genome Using Long-Read Sequencing and Chromosome Conformation Capture (Hi-C) Technologies. Diversity. 2021;13:668. doi: 10.3390/d13120668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bista I, et al. Genomics of cold adaptations in the Antarctic notothenioid fish radiation. Nat. Commun. 2023;14:3412. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38567-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera-Colón AG, et al. Genomics of secondarily temperate adaptation in the only non-Antarctic icefish. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023;40:msad029. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msad029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balushkin A, Korolkova E. New species of plunderfish Pogonophryne favosa sp. n.(Artedidraconidae, Notothenioidei, Perciformes) from the Cosmonauts Sea (Antarctica) with description in artedidraconids of unusual anatomical structures-convexitas superaxillaris. J. Ichthyol. 2013;53:562–574. doi: 10.1134/S0032945213050020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamburrini M, et al. The hemoglobins of the Antarctic fishes Artedidraco orianae and Pogonophryne scotti: amino acid sequence, lack of cooperativity, and ligand binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32452–32459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ward RD, Zemlak TS, Innes BH, Last PR, Hebert PD. DNA barcoding Australia’s fish species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2005;360:1847–1857. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chin C-S, et al. Phased diploid genome assembly with single-molecule real-time sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:1050–1054. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker BJ, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:1303.3997v2 [q-bio.GN] (2013).

- 36.Roach MJ, Schmidt SA, Borneman AR. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinform. 2018;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2485-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durand NC, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 2016;3:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dudchenko O, et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 2017;356:92–95. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Durand NC, et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubley, R. & Smit, A. F. RepeatModeler Open-1.0. (2008).

- 41.Bao Z, Eddy SR. Automated de novo identification of repeat sequence families in sequenced genomes. Genome Res. 2002;12:1269–1276. doi: 10.1101/gr.88502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.UniProt Consortium UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D480–D489. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ou S, Jiang N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176:1410–1422. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellinghaus D, Kurtz S, Willhoeft U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Z, Wang H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W265–W268. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haas BJ, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:1–22. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haas BJ, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5654–5666. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lomsadze A, Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6494–6506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brůna T, Lomsadze A, Borodovsky M. GeneMark-EP+: eukaryotic gene prediction with self-training in the space of genes and proteins. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2020;2:lqaa026. doi: 10.1093/nargab/lqaa026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;39:D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones P, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Götz S, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.BioBam Bioinformatics. OmicsBox-Bioinformatics made easy. (2019).

- 58.Moriya Y, Itoh M, Okuda S, Yoshizawa AC, Kanehisa M. KAAS: an automatic genome annotation and pathway reconstruction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W182–W185. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kanehisa M, Sato Y. KEGG Mapper for inferring cellular functions from protein sequences. Protein Sci. 2020;29:28–35. doi: 10.1002/pro.3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bryant DM, et al. A tissue-mapped axolotl de novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Rep. 2017;18:762–776. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Punta M, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Almagro Armenteros JJ, et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krogh A, Larsson B, Von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1832-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hedges SB, Dudley J, Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2971–2972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Han MV, Thomas GW, Lugo-Martinez J, Hahn MW. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:1987–1997. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun, J. et al. OrthoVenn3: an integrated platform for exploring and visualizing orthologous data across genomes. Nucleic Acids Res., gkad313 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.2023. NCBI GenBank. JAPTMU000000000

- 71.2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP304454

- 72.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rhie A, Walenz BP, Koren S, Phillippy AM. Merqury: reference-free quality, completeness, and phasing assessment for genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 2020;21:1–27. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02134-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2023. NCBI GenBank. JAPTMU000000000

- 2023. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRP304454

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All bioinformatic software and pipeline used in this study were implemented according to the protocols provided by the software developers. The versions and parameters for each software can be found in the Methods section. Unless otherwise stated, default parameters were employed.