Abstract

Purpose:

The current study investigated the extent to which interparental support reduced pregnancy stress and subsequent postpartum bonding impairments with infant. We hypothesized that receiving higher quality partner support would be associated with decreased maternal pregnancy-related concerns, and less maternal and paternal pregnancy stress which, in turn, would predict fewer parent-infant bonding impairments.

Methods:

157 cohabiting couples completed semi-structured interviews and questionnaires once during pregnancy and twice postpartum.

Results:

Path analyses with tests of mediation were employed to test our hypotheses. Higher quality support received by mothers was associated with lower maternal pregnancy stress which, in turn, predicted fewer mother-infant bonding impairments. An indirect pathway of equal magnitude was observed for fathers. Dyadic pathways also emerged such that higher quality support received by fathers was associated with lower maternal pregnancy stress which reduced mother-infant bonding impairments. Similarly, higher quality support received by mothers reduced paternal pregnancy stress and subsequent father-infant bonding impairments. Hypothesized effects reaching statistical significance (p < .05) were small to moderate in magnitude.

Conclusion:

These findings have important theoretical and clinical implications in demonstrating the critical role of both receiving and providing high quality interparental support to reduce pregnancy stress and subsequent postpartum bonding impairments for mothers and fathers. Results also highlight the utility of investigating maternal mental health in the couple context.

Keywords: partner support quality, prenatal stress, postpartum bonding

Introduction

The first six months postpartum is a critical time for the developing bond between mother and infant (Kinsey & Hupcey, 2013; Muzik et al., 2013); however, elevated stress during pregnancy can lead to significant bonding impairments (e.g., decreased emotional closeness; Zanardo et al., 2021). The partner of the pregnant person can also experience elevated prenatal stress (e.g., apprehension about postpartum caregiving; Hildingsson & Thomas, 2014; Nilsson et al., 2018; Philpott et al., 2017; Scorza et al., 2021) which can undermine healthy bonding between father and infant (Bieleninik et al., 2021). This is problematic because a stronger bond between mother and infant is associated with better attachment quality, lower colic rating (i.e., intense crying), and better infant temperament (Le Bas et al., 2020). Further, father-infant bonding impairments uniquely predict infant socioemotional dysfunction controlling for mother-infant bonding (Ramsdell & Brock, 2021), and greater disengagement during father-infant interactions predicts infant externalizing behaviors (Ramchandani et al., 2013). The current study aimed to examine whether receiving high quality interparental support (e.g., emotional validation and listening, tangible support such as help around the house) reduces prenatal stress—for both mothers and their partners—to reduce subsequent postpartum bonding impairments.

Social support is an interpersonal process that promotes adaptive functioning in the context of stress (Cohen, 2004; Eisenberger, 2013; Feeney & Collins, 2015). For individuals in committed intimate relationships, one of the most critical sources of support is one’s partner, and interparental support appears to be especially important during pregnancy, perhaps due to the shared experience of navigating pregnancy and childbirth as a couple. For example, Stapleton et al. (2012) found that women who reported stronger emotional support from their partner during pregnancy experienced less postpartum emotional distress.

Typically, it is assumed that receiving more frequent support from one’s partner is associated with better outcomes; however, the quality of support received, and whether it is an optimal match to what is required to cope with stress, might be a more important consideration (Bar-Kalifa & Rafaeli, 2013; Brock & Lawrence, 2010; Lorenzo et al., 2018; McLeod et al., 2020). There are various types of support that can be provided in response to someone’s experience of stress (Southwick et al., 2016) such as emotional (e.g., talking and listening), tangible (e.g., direct and indirect helping behaviors), informational (e.g., giving advice), esteem (e.g., providing reassurance), or network support (e.g., spending time together) (Lawrence et al., 2011, 2009). Yet, individuals have unique support preferences that depend on the context (e.g., apprehension about childbirth), so attention must be paid to whether the support recipient is receiving support that is a good match to their coping needs (Brock & Lawrence, 2010). Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that satisfaction with support received during pregnancy is important for reducing maternal prenatal stress (Racine et al., 2019).

Because high quality interparental support has the potential to reduce the experience of acute stress during pregnancy, it might also prevent adverse postpartum outcomes that result from elevated maternal stress. For example, in a recent study, parents who exhibited better postpartum bonding with their infant reported higher levels of partner support and less parenting stress (de Cock et al., 2016). Although this study was important for identifying interparental support as a potentially critical factor in postpartum bonding, support was measured using a 7-item self-report questionnaire assessing the quantity of support received, overlooking the quality of support (i.e., degree to which support matches the unique needs of the recipient).

The Present Study

Research has predominantly focused on the well-being of mothers during pregnancy, largely ignoring the experiences of their partners, such as elevations in prenatal stress (Skjothaug et al., 2018). Further, there is a critical need for research identifying factors that reduce stress experienced by both mothers and their partners during pregnancy to subsequently promote healthy bonding between parent and infant. In this longitudinal study of mixed-sex couples, we hypothesized that mothers who received higher quality partner support would report less perceived stress during pregnancy and fewer concerns about childbirth which, in turn, would predict fewer mother-infant bonding impairments during the first 6 months postpartum. We also hypothesized that when fathers had access to higher quality partner support, this would predict less stress during pregnancy and fewer father-infant bonding impairments.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participant demographics are described in Table 1. Flyers and brochures were broadly distributed to businesses and clinics frequented by pregnant women (e.g., obstetric clinics). Eligibility criteria included that participants were (a) 19 years of age or older, (b) English speaking, (c) pregnant at the time of the initial appointment, (d) both biological parents of the child (to test aims beyond the scope of this study), (e) singleton pregnancy, and (f) in a committed intimate relationship and cohabiting. Of the 159 couples who enrolled, two were excluded from subsequent analyses due to diagnosis of trisomy 21 and miscarriage.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Mothers | Fathers | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean (SD) or % | ||

|

| ||

| Age (years) | 28.67 (4.27) | 30.56 (4.52) |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 83.6% | 85.5% |

| White, Hispanic or Latinx | 5.7% | 1.9% |

| More than one race | 6.9% | 5.7% |

| Black or African American | 0.6% | 3.8% |

| Asian | 2.5% | 2.5% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Trimester of Pregnancy | ||

| First | 3.1% | |

| Second | 38.4% | |

| Third | 58.5% | |

|

| ||

| Couple | ||

|

| ||

| First-time parenthood | 57.9% | |

| Length of relationship (months) | 81.90 (49.59) | |

| Length of cohabitation (months) | 61.00 (41.80) | |

| Married | 84.9% | |

Note. N = 159. Low-income status was calculated using federal guidelines and adjusted for household size.

Low-income status 49.1 %

There were three waves of data collection which took place from February 2016 to October 2018. Both partners attended a three-hour laboratory appointment during pregnancy and completed a semi-structured interview and questionnaires in separate rooms. All participants provided written informed consent at the start of the appointment. Participants were compensated with $50 ($100 per couple). At 1 month (M = 1.12 months, SD = 0.29) and 6 months (M = 6.32 months, SD = 0.36) postpartum, each parent completed questionnaires from home and received $25 at each wave ($50 per couple). Participation rates at follow-up assessments were 92.4% at 1 month (90% of which included reports from both parents in a dyad) and 89.2% at 6 months (87% of which included reports from both parents of a dyad). Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university where the research was conducted (IRB #: 20151215700EP).

Measures

Partner Support (Pregnancy).

The Relationship Quality Interview (RQI; Lawrence et al., 2011, 2009) was used to assess the quality of support received by each partner over the past 6 months, including the match between desired and received levels of support. Open-ended questions, followed by closed ended questions, are asked to obtain novel contextual information about relationship functioning, and concrete behavioral indicators facilitate objective ratings. Interviewers independently rated support on a scale from 1–9 with the following anchors: 1 (partner provides no support or provides support but it is not what the participant wants; partner dismisses or ignores requests for support or alone time or responds with criticism), 5 (there is some mismatch between type of support received and type desired), 9 (partner is excellent at providing support and always responds well to requests for support). Partners were interviewed separately by different interviewers. The RQI has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (Lawrence et al., 2011, 2009). In the present study, interviewers completed coding training and participated in consensus and recalibration meetings. A different research assistant coded each partner from the same couple, and to ensure maximum objectivity, coders were instructed not to discuss interviews from the same couple. 20% of the interviews were randomly assigned and double-coded to assess interrater reliability (M intraclass correlation = .91, one-way random model, single rater ICC).

General Levels of Subjective Stress (Pregnancy).

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen et al., 1983) is a 14-item measure of subjective experiences of stress consisting of 7 positive and 7 negative statements assessing an individual’s thoughts and feelings pertaining to stress (e.g., “in the last month how often have you felt nervous and stressed?”). Parents were asked to rate the frequency of such thoughts during the last month on a 5-point Likert scale, from 0 – “never” to 4 – “very often”. The 7 positive items were reverse scored, and all 14 items were summed to generate an overall subjective stress score. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .83). The PSS has demonstrated good validity and reliability in diverse perinatal samples (Giurgescu et al., 2015; Solivan et al., 2015; Staneva et al., 2015).

Maternal Concerns about Pregnancy and Childbirth (Pregnancy).

The Pregnancy-Related Anxiety scale is a 10-item scale that measures maternal anxiety including anticipation of prenatal and childbirth complications (Rini et al., 1999). Example statements include “I am concerned about developing medical problems during my pregnancy” and “I am concerned about losing the baby.” Mothers were asked to rate items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0=never/not at all to 3=a lot/very much thinking about the last month. Scores range from 10 to 40, with higher scores indicating more pregnancy-related anxiety. This scale demonstrated good internal consistency in the present study (Cronbach’s α = .86). This measure has demonstrated good validity and reliability for assessing concerns about pregnancy and childbirth (Bayrampour et al., 2016; Lebel et al., 2020; Moyer et al., 2020).

Parent-Infant Impaired Bonding (1 and 6 Months Postpartum).

The Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire (PBQ; Brockington et al., 2001) is a 25-item, factor-analytically derived, parent-report measure of a parent’s feelings or attitudes toward their baby. Parents rate their agreement with statements (e.g., “I feel close to my baby”) on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from always (score = 5) to never (score = 0). Items from the impaired bonding subscale were summed at each time point (reverse coding items that represent positive feelings and attitudes). Repeated measures at 1 month and 6 months were highly correlated for both mothers (r = 0.68, p < .001) and fathers (r = 0.75, p < .001), and were averaged to obtain a robust and reliable score of parent-infant impaired bonding across the first 6 months of the postpartum period. Scores could range from 0–125 with higher scores indicating greater impaired bonding. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = .82 at 1 month and α = .78 at 6 months).

Data Analytic Strategy

The hypothesized parallel mediation model was tested in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used to address missing data (Enders, 2010). Covariance coverage ranged from .83 to 1.00. The couple was the unit of analysis. We implemented features of actor-partner interdependence modeling (APIM) for distinguishable dyads ((Kenny et al., 2020)), and the couple was used as the unit of analysis. We modeled both actor (e.g., Father X → Father Y) and partner (e.g., Father X → Mother Y) paths. Residuals of mediators (i.e., measures of stress) were covaried. Residuals of outcomes (i.e., bonding impairments) were covaried. We tested for indistinguishability of paths across partners (e.g., mother support → mother stress; father support → father stress). If the fit of the model was not improved by allowing paths to differ across partners, we retained the equality constraint and concluded that the parameters did not significantly differ from one another. We applied the following criteria to establish adequate global model fit: CFI above .95; RMSEA and SRMR under .05. A bias-corrected bootstrap approach (Shrout & Bolger, 2002) was used with 10,000 resamples drawn for estimating indirect effects which an empirical approximation of sampling distributions of effects to produce confidence intervals (CI) of estimates. Data management and analysis procedures for this project were registered (https://osf.io/hprk8), and we made no deviations from that plan.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are reported in Table 2. Tests of mean differences across partners are reported in Table 3 and suggest that mothers reported higher levels of perceived stress during pregnancy as compared to fathers. In contrast, differences in quality of support received (measured during pregnancy) and postpartum bonding impairments (i.e., mean of 1-month and 6-month parent reports) between mothers and fathers did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1. Interparental Support (F) | 1.00 | ||||||

| 2. Interparental Support (M) | .10 | 1.00 | |||||

| 3. Perceived Stress (F) | −.26*** | −.17* | 1.00 | ||||

| 4. Perceived Stress (M) | −.15 | −.26** | .17* | 1.00 | |||

| 5. Pregnancy Concerns (M) | .03 | −.17* | −.04 | .38*** | 1.00 | ||

| 6. Impaired Bonding (F) | −.17 | −.00 | .17 | −.02 | .11 | 1.00 | |

| 7. Impaired Bonding (M) | .01 | −.01 | .20* | .35*** | .19* | .34*** | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 6.83 | 6.58 | 12.91 | 14.32 | 18.08 | 11.45 | 9.93 |

| SD | 1.09 | 1.32 | 6.23 | 5.73 | 5.52 | 9.62 | 7.31 |

| N | 157 | 157 | 156 | 157 | 156 | 104 | 124 |

Note. F = fathers, M = mothers. Interparental Support (F) = the quality of support fathers received from mothers during pregnancy. Interparental Support (M) = the quality of support mothers received from fathers. Perceived stress and pregnancy concerns were reported during pregnancy. Impaired bonding scores were obtained by averaging reports at 1-month and 6-months postpartum.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .00

Table 3.

Paired Sample T-tests

| Mothers (n=157) | Fathers (n=157) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Outcome Variables | M(SD) | M(SD) | t | P |

|

| ||||

| Prenatal Perceived Stress | 14.35(5.74) | 12.91(6.23) | −2.32 | .02 |

| Interparental Support Quality | 6.58(1.32) | 6.83(1.09) | 1.92 | .06 |

| Postpartum Impaired Bonding | 9.92(7.42) | 11.76(9.73) | 1.82 | .07 |

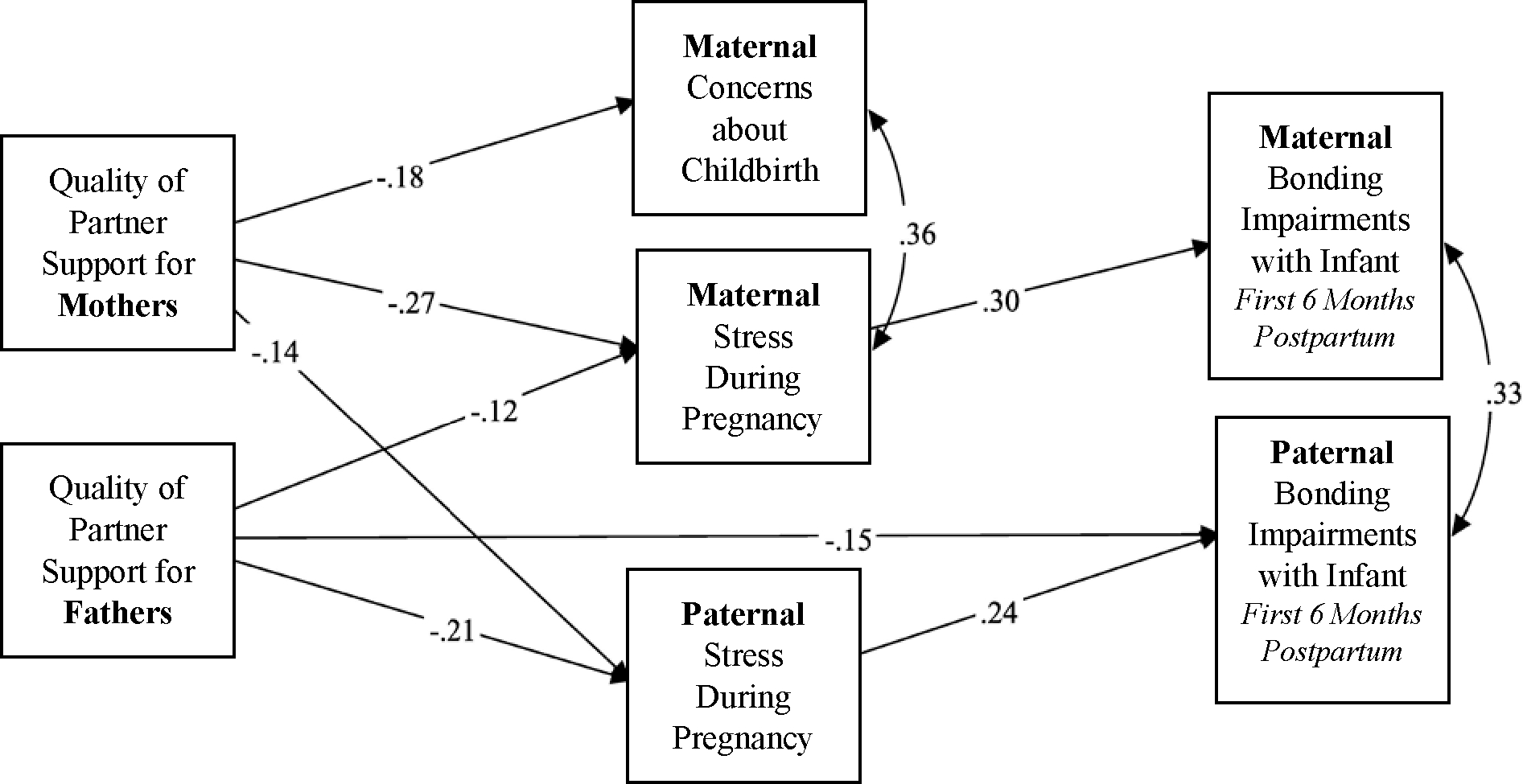

Tests of equality constraints suggested that there were no gender differences in paths with one exception—the association between quality of support received by fathers and paternal bonding impairments with infants (controlling for the mediators) was significantly larger than the corresponding path for mothers, χ2(1) = 7.79, p = .005. The model was respecified with the necessary equality constraints. The final model had excellent global fit (CFI = .984; RMSEA = .044, 95% CI [0.000, 0.126]; SRMR = .023; χ2(5) = 6.52, p = .259). Results of the hypothesized model are reported in Figure 1, Table 4 (direct paths), and Table 5 (covariances). There was evidence of significant mediation as demonstrated by bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs. Maternal stress mediated the link between maternal support and maternal bonding impairments, b = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.376, −0.115], and an indirect pathway of equal magnitude was observed for fathers, b = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.376, −0.115]. Partner paths were also significant with support quality in one partner associated with stress levels in the other partner. Maternal stress mediated the link between paternal support and maternal bonding impairments, b = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.249, −0.038], and an indirect pathway of equal magnitude was observed such that paternal stress mediated the link between maternal support and paternal bonding impairments, b = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.249, −0.038].

Figure 1. Summary of Model Results.

Only significant paths are depicted (p < .05). Standardized estimates are reported. Although not depicted, low-income status, week of pregnancy when prenatal data were collected, and duration of interparental relationship (in months) were controlled for in the model. The unstandardized solution for the full model is reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Estimates of Direct Paths

| Unstandardized Estimate | SE | p | Standardized Estimate | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Upper | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Outcome: Maternal Bonding Impairments | R2 = 12.4% | |||||

| M Pregnancy Concerns | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.461 | 0.07 | −0.064 | 0.188 |

| P Stress During Pregnancy | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.144 | 0.10 | −0.013 | 0.135 |

| M Stress During Pregnancy | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.30 | 0.112 | 0.261 |

| M Received Partner Support | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.218 | 0.10 | −0.181 | 0.668 |

| P Received Partner Support | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.102 | 0.11 | −0.081 | 0.812 |

| Week of Pregnancy | −0.02 | 0.04 | 0.528 | −0.05 | −0.093 | 0.053 |

| Low Income Status | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.309 | 0.09 | −0.630 | 1.869 |

| Duration of Interparental Relationship | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.128 | 0.14 | −0.003 | 0.023 |

| Outcome: Paternal Bonding Impairments | R2 = 13.0% | |||||

| M Pregnancy Concerns | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.162 | 0.12 | −0.036 | 0.248 |

| P Stress During Pregnancy | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.24 | 0.112 | 0.261 |

| M Stress During Pregnancy | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.144 | 0.07 | −0.013 | 0.135 |

| M Received Partner Support | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.102 | 0.11 | −0.081 | 0.812 |

| P Received Partner Support | −0.64 | 0.33 | 0.048 | −0.15 | −1.300 | −0.012 |

| Week of Pregnancy | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.804 | −0.02 | −0.125 | 0.087 |

| Low Income Status | 0.11 | 0.85 | 0.902 | 0.01 | −1.521 | 1.836 |

| Duration of Interparental Relationship | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.050 | 0.20 | 0.001 | 0.038 |

| Outcome: Maternal Pregnancy Concerns | R2 = 4.0% | |||||

| M Received Partner Support | −0.77 | 0.37 | 0.036 | −0.19 | −1.503 | −0.045 |

| P Received Partner Support | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.489 | 0.05 | −0.465 | 0.863 |

| Week of Pregnancy | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.753 | 0.02 | −0.085 | 0.118 |

| Low Income Status | −0.75 | 1.00 | 0.451 | −0.07 | −2.735 | 1.188 |

| Duration of Interparental Relationship | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.359 | −0.08 | −0.028 | 0.011 |

| Outcome: Maternal Stress | R2 = 13.3% | |||||

| M Received Partner Support | −1.20 | 0.23 | 0.000 | −0.27 | −1.639 | −0.752 |

| P Received Partner Support | −0.65 | 0.24 | 0.006 | −0.12 | −1.150 | −0.206 |

| Week of Pregnancy | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.080 | 0.14 | −0.015 | 0.226 |

| Low Income Status | 0.29 | 0.93 | 0.757 | 0.03 | −1.598 | 2.082 |

| Duration of Interparental Relationship | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.113 | −0.13 | −0.034 | 0.003 |

| Outcome: Paternal Stress | R2 = 13.6% | |||||

| M Received Partner Support | −0.65 | 0.24 | 0.006 | −0.14 | −1.150 | −0.206 |

| P Received Partner Support | −1.20 | 0.23 | 0.000 | −0.21 | −1.639 | −0.752 |

| Week of Pregnancy | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.070 | 0.12 | −0.010 | 0.200 |

| Low Income Status | 1.85 | 1.02 | 0.071 | 0.15 | −0.163 | 3.828 |

| Duration of Interparental Relationship | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.147 | −0.13 | −0.038 | 0.006 |

Note. M = Maternal. P = Paternal. Significant effects are bolded. 95% CI = bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval.

Table 5.

Covariance Estimates

| Unstandardized Estimate | SE | p | Standardized Estimate | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Residual Covariances | ||||||

| M Bonding – P Bonding | 4.71 | 1.33 | 0.000 | 0.33 | 2.466 | 7.758 |

| M Concerns – M Stress | 10.53 | 2.62 | 0.000 | 0.36 | 6.083 | 16.647 |

| M Concerns – P Stress | −2.05 | 2.36 | 0.385 | −0.07 | −6.641 | 2.566 |

| M Stress – P Stress | 1.86 | 2.44 | 0.446 | 0.06 | −2.683 | 6.921 |

| Covariances Among Predictors | ||||||

| M Support – P Support | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.161 | 0.10 | −0.052 | 0.353 |

| Week of Pregnancy – M Support | 0.18 | 0.81 | 0.821 | 0.02 | −1.316 | 1.860 |

| Week of Pregnancy – P Support | 0.53 | 0.64 | 0.411 | 0.06 | −0.711 | 1.817 |

| Low Income – M Support | −0.05 | 0.05 | 0.330 | −0.08 | −0.149 | 0.052 |

| Low Income – P Support | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.797 | 0.02 | −0.071 | 0.096 |

| Low Income – Week of Pregnancy | −0.28 | 0.30 | 0.348 | −0.08 | −0.889 | 0.308 |

| Relationship Duration – M Support | 1.45 | 5.37 | 0.787 | 0.02 | −8.727 | 12.194 |

| Relationship Duration – P Support | 2.57 | 3.90 | 0.509 | 0.05 | −4.946 | 10.220 |

| Relationship Duration – Week | 29.90 | 31.51 | 0.343 | 0.08 | −34.244 | 91.003 |

| Relationship Duration – Low Income | −10.26 | 1.80 | 0.000 | −0.42 | −13.747 | −6.790 |

Note. M = Maternal. P = Paternal. Significant covariances are bolded. 95% CI = bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval.

Discussion and Conclusions

Results of the present study suggest that higher quality interparental support might serve as a critical resource for preventing parental bonding impairments with infant during the first six months postpartum by reducing levels of prenatal stress. This mediation pathway was supported for not only mothers, but also fathers in this sample of mixed-sex couples, demonstrating the importance of promoting access to high quality support for both partners during pregnancy, and highlighting the potential for paternal prenatal stress—not just maternal stress—to undermine healthy bonding with infant. Results build on prior research illustrating the role of partner support in reducing maternal stress during pregnancy (e.g., Racine et al., 2019; Stapleton et al., 2012) and promoting mother-infant bonding (e.g., de Cock et al., 2016) but highlight that importance of having access to high quality support, meeting the unique coping needs of parents during this stressful transition. This is consistent with past research demonstrating that greater satisfaction with support reduces prenatal stress (e.g., Racine et al., 2019). Further, our work builds on research suggesting that higher levels of partner support can prevent postpartum bonding impairments (de Cock et al., 2016) by demonstrating that higher quality support received by one partner reduces stress experienced by both partners, reducing bonding impairments in both mother-infant and father-infant dyads. This highlights the far-reaching implications of receiving high quality interparental support for the family system.

It was notable that when mothers received higher quality partner support, this was associated with fewer concerns about childbirth; however, this specific form of stress was not uniquely associated with bonding when controlling for subjective stress levels. This suggests that it might be the overall experience of being “stressed” and not feeling capable of handling that stress that drives bonding impairments, as opposed to concerns specific to pregnancy. Nonetheless, pregnancy-related concerns might emerge as uniquely predictive of other postpartum outcomes (e.g., maternal depression) that play a critical role in parent-infant bonding. Further, it was interesting that partner support had a unique direct effect on reducing postpartum bonding impairments for fathers suggesting that support potentially influences father-infant bonding through other mechanisms beyond stress (e.g., by promoting other qualities of the interparental relationship that have been linked to father-infant bonding such as quality of sex during pregnancy; Ramsdell & Brock, 2021).

Strengths, Limitations, and Implications

The present study has several methodological strengths. First, prenatal research identifying interpersonal sources of resiliency have largely relied on self-report questionnaires (e.g., Bäckström et al., 2018; Fink et al., 2020). Further, as previously noted, most research considers the amount of support received without consideration of whether that support is actually helpful to the recipient. In the present study, we implemented a semi-structured interview administered to both partners during pregnancy to obtain scores of partner support quality, while also considering the unique needs and preferences of the support recipient. Second, we obtained multiple reports of parent-infant bonding impairments (at 1 and 6 months postpartum) for a reliable measure of bonding during the first 6 months postpartum, considered the most critical period for establishing a strong bond between parent and infant (Brody, 1981; Kinsey & Hupcey, 2013; Muzik et al., 2013). Third, in addition to assessing general levels of perceived stress (e.g., feeling nervous or stressed, not feeling capable of coping) in both mothers and fathers, we also assessed the degree to which mothers were experiencing concerns about giving birth (e.g., I am afraid that I will be harmed during delivery), a form of stress that is specific to the perinatal period and unique to mothers. Finally, we tested our hypotheses in an integrated, dyadic model that not only accounted for actor paths (e.g., maternal stress → maternal bonding impairments) but also partner paths (e.g., paternal stress → maternal bonding impairments). The potential for the experiences of one partner during pregnancy to spill over into the experiences of the other partner has been largely overlooked. This dyadic approach also allowed us to examine whether there were meaningful gender differences in hypothesized effects (e.g., maternal stress was not more harmful for postpartum bonding than paternal stress).

Nonetheless, we also acknowledge several limitations. First, postpartum bonding impairments were assessed using a self-report scale which could be strengthened by implementing observational data capturing parent-infant interactions. Relatedly, we assessed subjective stress which could be complimented with more objective assessments (e.g., physiological biomarkers of stress; Vaessen et al., 2021). Second, in the absence of a validated measure, it is unclear whether the partner of the birthing person experienced concerns about pregnancy and childbirth that were detrimental to postpartum bonding. Future research should aim to develop an instrument that assesses the pregnancy and childbirth experience from the partner’s perspective, including concerns that might be unique from those reported by the birthing person (e.g., lack of control as a bystander in childbirth). Third, support and stress were assessed at the same time during pregnancy despite higher quality support being conceptualized as a predictor of (less) stress. Although our measure of support was intended to capture enduring patterns of support interactions unfolding over the past 6 months, whereas stress measures inquired about current levels of stress, it is important to acknowledge that stress and support likely have a bidirectional link, and that stress has the potential to impair responsiveness to partner distress. Fourth, we did not include maternal depression in our model, which is potentially a mediator between pregnancy stress and postpartum bonding impairments. The marital and family discord model of depression suggests that interparental relationship quality (including support) also plays an important role in depression (Beach, 2014). Therefore, high quality support might reduce depression (Kumar et al., 2022), which is robustly linked to bonding impairments (Dubber et al., 2015). Finally, participants in the sample were relatively privileged, White, mixed-sex couples. Future research examining these pathways should strive to include parents who identify as a sexual, gender, racial, and/or ethnic minority. Greater attention must be paid to the unique experiences of parents who are navigating pregnancy while simultaneously coping with stress from experiences with marginalization and discrimination.

Despite these limitations, there are several implications of the present study. First, results suggest that perinatal researchers should routinely consider how the partner of the pregnant person in dual parenting households is coping with pregnancy, and the effect this has on their ability to bond with infant and engage in healthy parenting behaviors. It was notable that prenatal stress experienced by fathers in the present study had an effect on bonding with infant that was of similar magnitude to that of mothers, and that both mothers and fathers benefited from receiving high quality support.

Second, regarding clinical implications, this study highlights the importance of routinely screening for elevated subjective stress in both the pregnant person and their partner and providing resources to mitigate that stress. Further, our results suggest that teaching parents how to provide higher quality support to one another during pregnancy can ultimately promote the development of healthy parent-infant relationships—and subsequent child development—by reducing prenatal stress. Results also suggest that it might not be sufficient to broadly encourage “more support” when working with couples navigating pregnancy. Instead, attention must be paid to boosting communication and responsiveness between partners so that they can ask for what they need to effectively cope with stress and tailor their support provision to meet the unique needs of their partners.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families who participated in this research and the entire team of research assistants who contributed to various stages of the study. In particular, we thank Jennifer Blake, Erin Ramsdell, Kailee Groshans, and Frances Calkins for project coordination. We also thank Erin Ramsdell, Eric Phillips and Lauren Laifer for data management and processing.

Funding:

This research was funded by several internal funding mechanisms awarded to PI Rebecca Brock from the UNL Department of Psychology, the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund, and the UNL Office of Research and Economic Development. The project was also supported by the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences, 1U54GM115458. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Declarations

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval: This study received ethical approval from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Consent: All participants provided informed consent in writing prior to participation.

References

- Bäckström C, Kåreholt I, Thorstensson S, Golsäter M, & Mårtensson LB (2018). Quality of couple relationship among first-time mothers and partners during pregnancy and the first six months of parenthood. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 17, 56–64. 10.1016/j.srhc.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Kalifa E, & Rafaeli E (2013). Disappointment’s sting is greater than help’s balm: Quasi-signal detection of daily support matching. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(6), 956. 10.1037/a0034905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayrampour H, Ali E, McNeil DA, Benzies K, MacQueen G, & Tough S (2016). Pregnancy-related anxiety: A concept analysis. International journal of nursing studies, 55, 115–130. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach S (2014). The couple and family discord model of depression. Interpers Relationships Health Soc Clin Psychol Mech, 1, 133–155. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199936632.003.0007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bieleninik Ł, Lutkiewicz K, Jurek P, & Bidzan M (2021). Paternal postpartum bonding and its predictors in the early postpartum period: Cross-sectional study in a polish cohort. Frontiers in Psychology, 1112. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock RL, & Lawrence E (2010). Support adequacy in marriage: Observing the platinum rule. Support processes in intimate relationships, 519, 3–25. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195380170.003.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody S (1981). The concepts of attachment and bonding. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 29(4), 815–829. 10.1177/000306518102900403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676. 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock ES, Henrichs J, Vreeswijk CM, Maas AJ, Rijk CH, & van Bakel HJ (2016). Continuous feelings of love? The parental bond from pregnancy to toddlerhood. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 125. 10.1037/fam0000138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubber S, Reck C, Muller M, & Gawlik S (2015). Postpartum bonding: the role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal-fetal bonding during pregnancy. Arch Womens Ment Health, 18(2), 187–195. 10.1007/s00737-014-0445-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI (2013). An empirical review of the neural underpinnings of receiving and giving social support: implications for health. Psychosomatic medicine, 75(6), 545. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829de2e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Feeney BC, & Collins NL (2015). A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(2), 113–147. 10.1177/1088868314544222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink E, Browne WV, Kirk I, & Hughes C (2020). Couple relationship quality and the infant home language environment: Gender-specific findings. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(2), 155. 10.1037/fam0000590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, Misra DP, Sealy-Jefferson S, Caldwell CH, Templin TN, Slaughter-Acey JC, & Osypuk TL (2015). The impact of neighborhood quality, perceived stress, and social support on depressive symptoms during pregnancy in African American women. Social Science & Medicine, 130, 172–180. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildingsson I, & Thomas J (2014). Parental stress in mothers and fathers one year after birth. Journal of reproductive and infant psychology, 32(1), 41–56. 10.1080/02646838.2013.840882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2020). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey CB, & Hupcey JE (2013). State of the science of maternal–infant bonding: A principle-based concept analysis. Midwifery, 29(12), 1314–1320. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar SA, Franz MR, DiLillo D, & Brock RL (2022). Promoting resilience to depression among couples during pregnancy: The protective functions of intimate relationship satisfaction and self-compassion. Family Process, e12788. 10.1111/famp.12788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, & Giesbrecht G (2020). Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 5–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo JM, Barry RA, & Khalifian CE (2018). More or less: Newlyweds’ preferred and received social support, affect, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(7), 860. 10.1037/fam0000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S, Berry K, Hodgson C, & Wearden A (2020). Attachment and social support in romantic dyads: A systematic review. Journal of clinical psychology, 76(1), 59–101. 10.1002/jclp.22868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer CA, Compton SD, Kaselitz E, & Muzik M (2020). Pregnancy-related anxiety during COVID-19: a nationwide survey of 2740 pregnant women. Archives of women’s mental health, 23(6), 757–765. 10.1007/s00737-020-01073-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, & Muthén B (2010). Mplus user’s guide 6th edition. Los Angeles, California: Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Muzik M, Bocknek EL, Broderick A, Richardson P, Rosenblum KL, Thelen K, & Seng JS (2013). Mother–infant bonding impairment across the first 6 months postpartum: the primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Archives of women’s mental health, 16(1), 29–38. 10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson C, Hessman E, Sjöblom H, Dencker A, Jangsten E, Mollberg M, . . . Begley C. (2018). Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 18(1), 1–15. 10.1186/s12884-018-1659-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott LF, Leahy-Warren P, FitzGerald S, & Savage E (2017). Stress in fathers in the perinatal period: a systematic review. Midwifery, 55, 113–127. 10.1016/j.midw.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N, Plamondon A, Hentges R, Tough S, & Madigan S (2019). Dynamic and bidirectional associations between maternal stress, anxiety, and social support: the critical role of partner and family support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 252, 19–24. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani PG, Domoney J, Sethna V, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, & Murray L (2013). Do early father–infant interactions predict the onset of externalising behaviours in young children? Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 54(1), 56–64. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02583.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsdell EL, & Brock RL (2021). Interparental Relationship Quality During Pregnancy: Implications for Early Parent–Infant Bonding and Infant Socioemotional Development. Family Process, 60(3), 966–983. 10.1111/famp.12599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, & Sandman CA (1999). Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Health Psychology, 18(4), 333. 10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorza P, Merz EC, Spann M, Steinberg E, Feng T, Lee S, . . . Monk C. (2021). Pregnancy-specific stress and sensitive caregiving during the transition to motherhood in adolescents. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 21(1), 1–8. 10.1186/s12884-021-03903-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Bolger N (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological methods, 7(4), 422–445. 10.1037//1082-989x.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjothaug T, Smith L, Wentzel-Larsen T, & Moe V (2018). DOES FATHERS’PRENATAL MENTAL HEALTH BEAR A RELATIONSHIP TO PARENTING STRESS AT 6 MONTHS? Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(5), 537–551. 10.1002/imhj.21739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solivan AE, Xiong X, Harville EW, & Buekens P (2015). Measurement of perceived stress among pregnant women: a comparison of two different instruments. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(9), 1910–1915. 10.1007/s10995-015-1710-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick SM, Sippel L, Krystal J, Charney D, Mayes L, & Pietrzak R (2016). Why are some individuals more resilient than others: the role of social support. World psychiatry, 15(1), 77. 10.1002/wps.20282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staneva A, Bogossian F, Pritchard M, & Wittkowski A (2015). The effects of maternal depression, anxiety, and perceived stress during pregnancy on preterm birth: A systematic review. Women and Birth, 28(3), 179–193. 10.1016/j.wombi.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton LRT, Schetter CD, Westling E, Rini C, Glynn LM, Hobel CJ, & Sandman CA (2012). Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(3), 453. 10.1037/a0028332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaessen T, Rintala A, Otsabryk N, Viechtbauer W, Wampers M, Claes S, & Myin-Germeys I (2021). The association between self-reported stress and cardiovascular measures in daily life: A systematic review. PloS one, 16(11), e0259557. 10.1371/journal.pone.0259557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanardo V, Tedde F, Callegher CZ, Sandri A, Giliberti L, Manghina V, & Strafaceee G (2021). Postpartum bonding: the impact of stressful life events during pregnancy. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 1–8. 10.1080/14767058.2021.1937986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]