Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) by prior biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) use.

Methods

Data from a placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study of patients with active AS were analyzed. Patients received tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (BID) or placebo to week 16; all received open‐label tofacitinib 5 mg BID to week 48 and were stratified by prior treatment (bDMARD‐naive or tumor necrosis factor inhibitor [TNFi]–inadequate responder [IR], including bDMARD‐experienced [non‐IR]). Disease activity/safety were assessed throughout.

Results

Of 269 patients, 207 (77%) were bDMARD‐naive; 62 (23%) were in the TNFi‐IR subgroup. TNFi‐IR patients had higher baseline BMI (28.0 vs. 26.1 kg/m2), longer symptom duration (14.4 vs. 13.2 years), and lower concomitant conventional synthetic DMARD use (14.5% vs. 30.9%) than bDMARD‐naive patients. At week 16, for most outcomes, tofacitinib efficacy exceeded placebo for both subgroups and was sustained to week 48. At week 16, tofacitinib versus placebo differences were similar between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Assessment in Spondyloarthritis international Society 40 treatment difference [95% confidence interval]: 30.8% [19.1%‐42.6%] vs. 19.4% [1.7%‐37.0%]). Adverse event (AE) proportions were similar between tofacitinib‐treated bDMARD‐naive/TNFi‐IR patients (77.5%/77.4%) at week 48 with no deaths. A numerically higher proportion of tofacitinib‐treated TNFi‐IR versus bDMARD‐naive patients discontinued study drug (12.9% vs. 3.9%) or dose reduced/temporarily discontinued due to AEs (19.4% vs. 11.8%).

Conclusion

Tofacitinib efficacy exceeded placebo at week 16 for bDMARD‐naive/TNFi‐IR patients and was sustained to week 48. The absolute magnitude of responses was generally greater in bDMARD‐naive patients versus TNFi‐IR patients. More TNFi‐IR versus bDMARD‐naive patients discontinued or dose reduced/temporarily discontinued tofacitinib due to AEs. Small sample size and sample size differences between subgroups limited the interpretation.

INTRODUCTION

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), also known as radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (r‐axSpA) (1, 2), is a complex, inflammatory rheumatic disease that typically affects the sacroiliac joints, and often the spine (3). The prevalence of axSpA, which comprises both radiographic AS and nonradiographic axSpA (2), is thought to range from 0.9% to 1.4% in adults in the US, depending on the specific classification criteria used (4).

Current treatment guidelines recommend several interventions for the management of AS, including anti‐inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, and regular exercise (5, 6). Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) or interleukin (IL)‐17 antagonists, are typically used for the treatment of axSpA (5, 6). For patients with AS who are inadequate responders (IRs) or intolerant to bDMARDs, switching to a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor or to an alternative bDMARD is recommended (5, 6).

Tofacitinib is an oral JAK inhibitor approved for the treatment of AS. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in AS have been demonstrated in one phase 2 and one phase 3 randomized controlled trial (7, 8).

Prior exposure to bDMARD therapy in patients with AS may influence subsequent treatment response and drug tolerance, but this is currently not well understood for all pharmacologic therapies. In the context of AS, it is relevant to consider prior exposure to TNFi and IL‐17 antagonists, as both therapies are recommended for use post NSAID failure (5, 6). A TNFi‐IR group is of relevance because patients who receive tofacitinib in clinical practice are required to have failed TNFi therapy in certain locations, including the US (9). For example, separate post hoc analyses of phase 3 trials in patients with AS receiving IL‐17 antagonists (ixekizumab in bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients, and secukinumab in TNFi‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients) have suggested that bDMARD‐naive patients have numerically greater responses to treatment than TNFi‐experienced and TNFi‐IR patients (10, 11, 12, 13). A numerically lower proportion of bDMARD‐naive patients receiving ixekizumab experienced an adverse event (AE; weeks 16‐52) versus TNFi‐experienced patients (10). However, a cross‐trial comparison of the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib in patients with AS has suggested that bDMARD‐naive and bDMARD‐IR patients have similar responses to treatment (14, 15).

This post hoc analysis sought to assess the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib by prior bDMARD use (bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR) in adult patients with active AS enrolled in the tofacitinib phase 3 clinical trial (NCT03502616) (8).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and data

Data were from a phase 3, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of patients aged 18 years or older with active AS, conducted at 75 centers (NCT03502616). Full study design details have been reported previously (8). Briefly, in the double‐blind phase (weeks 0‐16), patients were randomized 1:1 to receive tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily (BID) or placebo. In the open‐label phase (weeks 16‐48), all patients (including those receiving placebo in the double‐blind phase) received open‐label tofacitinib 5 mg BID. Patients who were randomized and received at least one dose of study drug (full analysis set) were included in all analyses and at all time points. Patients could continue the following stable background therapies: NSAIDs, methotrexate (≤25 mg/week), sulfasalazine (≤3 g/day), and oral glucocorticoids (≤10 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Council for Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and was approved by the institutional review board and/or independent ethics committee for each study center. Patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

In this post hoc analysis, patients were stratified by prior bDMARD use into the following two subgroups: 1) bDMARD‐naive patients and 2) TNFi‐IR patients (IR to ≤2 TNFi). The TNFi‐IR subgroup also included TNFi‐experienced (non‐IR) patients.

All outcomes were assessed to week 16 (placebo‐controlled phase) and to week 48 (open‐label phase).

Clinical efficacy outcomes included the following: response rates for Assessment in Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) greater than or equal to 20% response (ASAS20), ASAS greater than or equal to 40% response (ASAS40), ASAS 5/6 response (ASAS 5/6), ASAS partial remission; Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score C‐reactive protein (ASDAS CRP) categories of clinically important improvement, major improvement, and inactive disease; Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) greater than or equal to 50% response (BASDAI50); and mean change from baseline in ASDAS, high‐sensitivity (hs)CRP (mg/dl), BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI) linear method, and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI).

Patient‐reported outcomes included change from baseline in AS Quality of Life (ASQoL); patient global assessment; morning stiffness (average of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI); Short Form‐36 Health Survey version 2 (SF‐36v2) Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS); Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy‐Fatigue (FACIT‐F) total, experience domain, and impact domain scores; total back pain; nocturnal spinal pain; EuroQol‐Five Dimensions‐Three Level Health Questionnaire (EQ‐5D‐3L) outcomes (mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression); and EQ‐Visual Analog Scale (EQ‐VAS; mm) for patient's self‐rated health.

Safety events, including AEs, serious AEs (SAEs), deaths, and discontinuations due to AEs, were analyzed through week 48.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographics, disease characteristics, prior/concomitant medications, and safety data were summarized descriptively using observed data by prior bDMARD use.

Efficacy analyses included only data collected while patients were on study treatment (ie, on‐drug data). The reported data are based on two databases: efficacy analyses up to week 16 (placebo‐controlled; data cutoff December 19, 2019) and week 48 (final data). The assessment of ASAS20 and ASAS40 response rates up to week 16 by prior bDMARD use was prespecified, and all other endpoints by prior bDMARD use were post hoc.

Binary efficacy endpoints (ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS categories, and BASDAI50) were assessed using the normal approximation to the difference of binomial proportions at each time point (weeks 2‐16 [data cutoff December 19, 2019] and weeks 24‐48 [final data]) comparing tofacitinib versus placebo, performed separately by prior bDMARD use. Ninety‐five percent confidence intervals (95% CIs) of the treatment difference were also generated. A missing response was considered as nonresponse.

For change from baseline in continuous efficacy endpoints with repeated measures at multiple visits (ASDAS, hsCRP [mg/dL], BASDAI, BASMI–linear method, BASFI, patient global assessment, morning stiffness [average of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI], FACIT‐F total, experience domain, and impact domain scores, total back pain, and nocturnal spinal pain), a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) was used (weeks 2‐16 [data cutoff December 19, 2019] and weeks 24‐48 [final data]), which included fixed effects of treatment group, visit, treatment group by visit interaction, baseline value, and baseline value by visit interaction, performed separately by prior bDMARD use. The model used a common unstructured variance–covariance matrix, without imputation for missing values.

For change from baseline in continuous efficacy endpoints with only a single post‐baseline visit measure (ASQoL, SF‐36v2 PCS and MCS, and EQ‐5L‐3D outcomes at week 16 [data cut‐off December 19, 2019]), an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was used, which included fixed effects of treatment group and baseline value, performed separately by prior bDMARD use. At week 48 (final data), these outcomes were analyzed using MMRM models. Missing values were not imputed. The least squares (LS) mean difference comparing tofacitinib versus placebo by visit was reported along with its 95% CIs from the MMRM and ANCOVA analyses.

In this analysis, only ASAS20 and ASAS40 by prior bDMARD use were prespecified endpoints. With the aim to assess if treatment effects were consistent between subgroups, no hypothesis testing was performed, and treatment comparisons were estimated without adjustment for multiplicity due to the post hoc nature of all other endpoints by prior bDMARD use. Efficacy of tofacitinib exceeding placebo was considered greater (though not statistically significant) if the 95% CIs of the treatment differences did not include zero. Efficacy of tofacitinib exceeding placebo was considered numerically greater if the 95% CIs of the treatment differences included zero. For treatment difference comparisons between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients, differences observed with nonoverlapping 95% CIs (tofacitinib vs. placebo) or standard errors (absolute response rates) were considered greater for the specific subgroup. Comparisons with overlapping 95% CIs and standard errors were considered as similar.

RESULTS

Patients

This analysis included 269 randomized and treated patients; 207 (77%) patients were bDMARD‐naive, and 62 (23%) patients were included in the TNFi‐IR subgroup. Of the 62 patients in the TNFi‐IR subgroup, 59 were TNFi‐IR (95.2%) and 3 were TNFi‐experienced (non‐IR) (4.8%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics, disease characteristics, and concomitant medications at baseline by prior bDMARD use

| bDMARD‐naive patients | TNFi‐IR a patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (n = 102) | Placebo (n = 105) | Total (N = 207) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (n = 31) | Placebo (n = 31) | Total (N = 62) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD) y | 41.9 (11.9) | 39.8 (10.8) | 40.8 (11.4) | 43.1 (11.8) | 40.7 (12.2) | 41.9 (11.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 90 (88.2) | 85 (81.0) | 175 (84.5) | 26 (83.9) | 23 (74.2) | 49 (79.0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 16 (15.7) | 20 (19.0) | 36 (17.4) | 9 (29.0) | 10 (32.3) | 19 (30.6) |

| White | 85 (83.3) | 85 (81.0) | 170 (82.1) | 22 (71.0) | 21 (67.7) | 43 (69.4) |

| BMI, mean (SD) kg/m2 | 26.3 (4.9) | 25.8 (5.1) | 26.1 (5.0) | 28.0 (7.6) | 28.0 (7.4) | 28.0 (7.5) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Never smoked | 59 (57.8) | 54 (51.4) | 113 (54.6) | 16 (51.6) | 18 (58.1) | 34 (54.8) |

| Former smoker | 17 (16.7) | 15 (14.3) | 32 (15.5) | 7 (22.6) | 4 (12.9) | 11 (17.7) |

| Current smoker | 26 (25.5) | 36 (34.3) | 62 (30.0) | 8 (25.8) | 9 (29.0) | 17 (27.4) |

| Geographic region, n (%) b | ||||||

| Asia | 14 (13.7) | 20 (19.0) | 34 (16.4) | 9 (29.0) | 10 (32.3) | 19 (30.6) |

| European Union | 47 (46.1) | 47 (44.8) | 94 (45.4) | 4 (12.9) | 8 (25.8) | 12 (19.4) |

| North America | 5 (4.9) | 5 (4.8) | 10 (4.8) | 11 (35.5) | 6 (19.4) | 17 (27.4) |

| Rest of the world | 36 (35.3) | 33 (31.4) | 69 (33.3) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | 14 (22.6) |

| History of psoriasis, yes, n (%) | 4 (3.9) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (2.4) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (4.8) |

| Disease characteristics | ||||||

| Disease symptom duration, mean (SD) y | 14.0 (9.8) | 12.5 (9.3) | 13.2 (9.5) | 14.6 (10.0) | 14.3 (10.1) | 14.4 (10.0) |

| Disease duration since diagnosis, mean (SD) y | 8.0 (8.8) | 6.3 (6.9) | 7.2 (7.9) | 11.9 (9.5) | 8.2 (7.1) | 10.1 (8.5) |

| HLA‐B27, positive, n (%) c | 92 (90.2) | 93 (88.6) | 185 (89.4) | 25 (80.6) | 25 (80.6) | 50 (80.6) |

| ASDAS, mean (SD) d | 3.8 (0.9) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.7) | 4.1 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.7) |

| BASFI, mean (SD) | 5.8 (2.3) | 5.7 (2.1) | 5.8 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.5) | 6.6 (2.0) | 6.2 (2.3) |

| BASDAI, mean (SD) | 6.5 (1.5) | 6.4 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.5) | 6.2 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.3) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| BASMI–linear method, mean (SD) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.3 (1.7) | 4.4 (1.7) | 4.6 (1.9) | 4.7 (1.9) | 4.7 (1.9) |

| hsCRP, mean (SD), mg/L | 16.4 (18.2) | 18.1 (21.1) | 17.3 (19.7) | 16.3 (14.1) | 17.8 (14.2) | 17.0 (14.1) |

| MASES >0, yes, n (%) | 57 (55.9) | 62 (59.0) | 119 (57.5) | 14 (45.2) | 19 (61.3) | 33 (53.2) |

| MASES, mean (SD) e | 3.7 (2.2) | 3.2 (1.9) | 3.4 (2.1) | 3.9 (3.5) | 5.0 (3.3) | 4.5 (3.4) |

| Patients with SJC (44) >0, yes, n (%) | 25 (24.5) | 28 (26.7) | 53 (25.6) | 8 (25.8) | 10 (32.3) | 18 (29.0) |

| SJC (44), mean (SD) f | 2.7 (2.5) | 3.6 (4.9) | 3.2 (3.9) | 5.5 (3.6) | 5.6 (6.1) | 5.6 (5.0) |

| Patient global assessment, mean (SD) | 7.0 (1.8) | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.6) | 7.4 (1.7) | 7.1 (1.7) |

| Total back pain, mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.8 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.5) | 7.3 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.6) |

| Nocturnal spinal pain, mean (SD) | 6.9 (1.9) | 6.7 (1.9) | 6.8 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.1) | 7.0 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.9) |

| Morning stiffness, mean (SD) g | 6.6 (1.9) | 6.5 (1.8) | 6.6 (1.9) | 6.5 (1.8) | 7.8 (1.9) | 7.2 (1.9) |

| Concomitant medications (day 1), yes, n (%) | ||||||

| csDMARDs | 26 (25.5) | 38 (36.2) | 64 (30.9) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (19.4) | 9 (14.5) |

| NSAIDs | 82 (80.4) | 81 (77.1) | 163 (78.7) | 24 (77.4) | 27 (87.1) | 51 (82.3) |

| Oral glucocorticoids | 8 (7.8) | 6 (5.7) | 14 (6.8) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (3.2) | 6 (9.7) |

| Analgesics | 5 (4.9) | 5 (4.8) | 10 (4.8) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (6.5) |

| Prior bDMARD use, a n (%) | ||||||

| Prior TNFi | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 62 (100) | |||

| TNFi‐IR | 29 (93.5) | 30 (96.8) | 59 (95.2) | |||

| TNFi‐experienced (non‐IR) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (4.8) | |||

| Prior IL‐17 antagonist | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

Abbreviations: ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disability Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; HLA‐B27, human leukocyte antigen B27; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; IL‐17, interleukin‐17; MASES, Maastricht Ankylosing Spondylitis Enthesitis Score; N = number of patients in analysis set; n = number of patients meeting the criterion; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; SJC, swollen joint count; TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

TNFi‐IR subgroup included 59 TNFi‐IR and 3 TNFi‐experienced patients without an inadequate response.

North America included Canada and the US; European Union included Bulgaria, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, and Poland; Asia included China and South Korea; rest of the world included Australia, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine.

If baseline HLA‐B27 results were not available, results after baseline were also included in the summary.

hsCRP values less than 2 mg/L set to 2 mg/L in the formula to derive ASDAS.

Summary included only patients with baseline MASES greater than 0.

Summary included only patients with baseline SJC (44) greater than 0.

Calculated as the average of questions 5 and 6 of the BASDAI, also known as Inflammation (each question is scored on a scale of 0‐10 of increasing severity).

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics are presented in Table 1. Mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 40.8 (11.4) and 41.9 (11.9) years in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients, respectively; most patients were male (bDMARD‐naive: 84.5%, TNFi‐IR patients: 79.0%) and White (bDMARD‐naive: 82.1%, TNFi‐IR patients: 69.4%). Patients in the TNFi‐IR subgroup had numerically longer disease duration since start of symptoms (mean [SD]; 14.4 [10.0] vs. 13.2 [9.5] years) and higher mean (SD) BMI (28.0 [7.5] vs. 26.1 [5.0] kg/m2) versus bDMARD‐naive patients. A numerically higher proportion of TNFi‐IR patients were from Asia (30.6%) and North America (27.4%) versus the European Union (19.4%) and rest of the world (22.6%). In the bDMARD‐naive subgroup, a numerically greater proportion were from the European Union (45.4%) and rest of the world (33.3%) versus Asia (16.4%) and North America (4.8%). Baseline disease activity measures and patient‐reported outcomes were generally similar between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Table 1).

A greater proportion of bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients were receiving concomitant conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs (30.9% vs. 14.5%). In both the bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR subgroups, fewer patients treated with tofacitinib versus placebo were also receiving concomitant csDMARDs (Table 1).

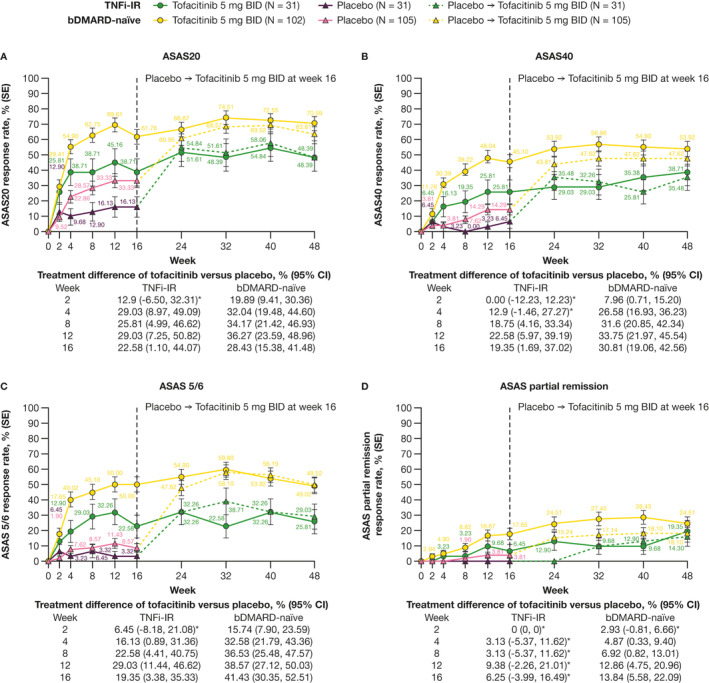

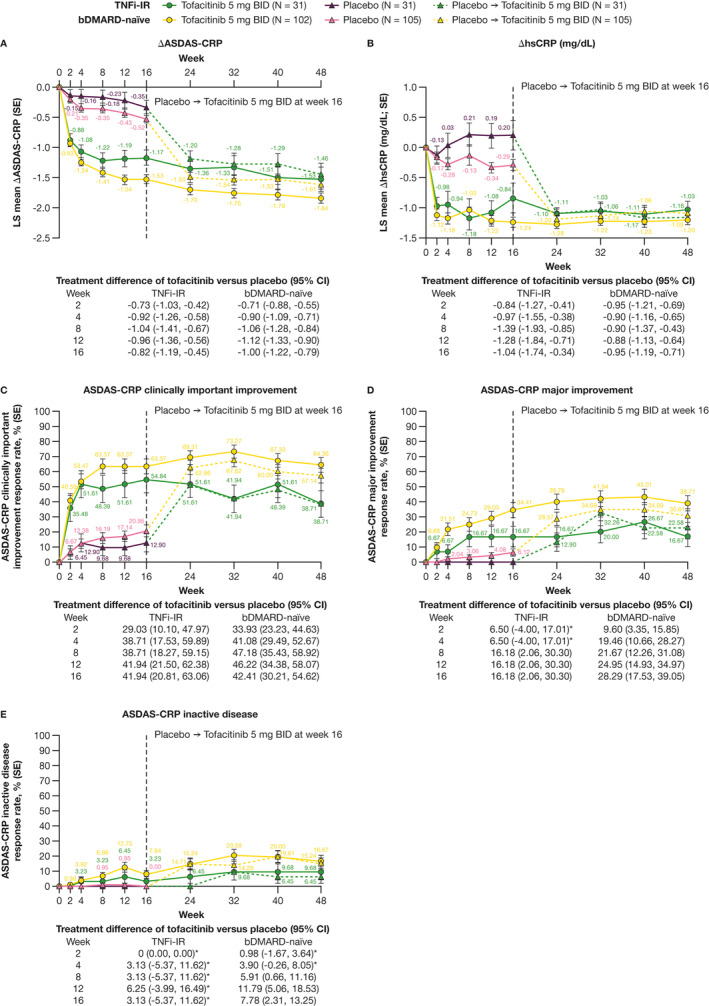

Clinical efficacy

At week 16, ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, and ASDAS response rates (clinically important improvement, major improvement), and LS mean change from baseline in ASDAS and hsCRP (mg/dL), were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Figure 1A‐C and Figure 2A‐D). ASAS partial remission and ASDAS inactive disease response rates were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in bDMARD‐naive patients only (Figure 1D and Figure 2E).

Figure 1.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg BID in bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients to week 48: (A) ASAS20, (B) ASAS40, (C) ASAS 5/6, and (D) ASAS partial remission response rates (nonresponder imputation). *95% CI includes 0. The number of patients evaluated in each treatment group and patient subgroup across time points may vary. ASAS, Assessment in Spondyloarthritis International Society; ASAS 5/6, ASAS 5/6 response; ASAS20, ASAS greater than or equal to 20% response; ASAS40, ASAS greater than or equal to 40% response; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; N, number of evaluable patients; SE, standard error; TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg BID in bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients to week 48: LS mean change from baseline in (A) ASDAS and (B) hsCRP (mg/dL) (MMRM) and response rates for ASDAS categories of (C) clinically important improvement, (D) major improvement, and (E) inactive disease (nonresponder imputation). *95% CI includes 0. The number of patients evaluated in each treatment group and patient subgroup across time points may vary. Δ, change from baseline; ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; N, number of evaluable patients; SE, standard error; TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

At week 16, differences in ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASAS partial remission, and ASDAS (clinically important improvement, major improvement, and inactive disease) response rates as well as LS mean change from baseline in ASDAS and hsCRP (mg/dL) for tofacitinib versus placebo were similar in magnitude between the bDMARD‐naive and the TNFi‐IR subgroups (Figure 1A‐D and Figure 2A‐E).

Efficacy improvements and response rates were generally maintained with open‐label tofacitinib from week 16 up to week 48 for each outcome and patient group (Figure 1A‐D and Figure 2A‐E). From weeks 4 to 48, absolute response rates with tofacitinib for ASAS20, ASAS40, and ASAS 5/6 were greater in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients (Figure 1A‐C). Similar observations were made for ASAS partial remission (weeks 16‐40; Figure 1D), LS mean change from baseline in ASDAS (weeks 12‐48; Figure 2A), and ASDAS clinically important improvement (weeks 24‐48; Figure 2C), major improvement (weeks 12‐48; Figure 2D), and inactive disease response rates (weeks 24‐40; Figure 2E). Improvements from baseline in hsCRP (mg/dL) were generally similar between subgroups (Figure 2B).

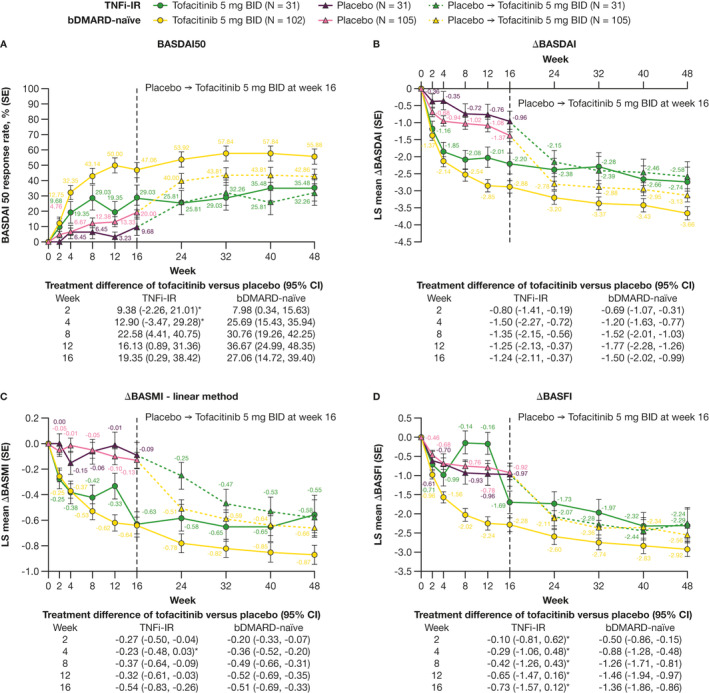

At week 16, BASDAI50 response rates, and LS mean change from baseline in BASDAI and BASMI, were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Figure 3A‐C). LS mean change from baseline in BASFI was greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in bDMARD‐naive patients only (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg BID in bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients to week 48: (A) BASDAI50 response rate (nonresponder imputation) and LS mean change from baseline in (B) BASDAI, (C) BASMI (linear method), and (D) BASFI (MMRM). *95% CI includes 0. The number of patients evaluated in each treatment group and patient subgroup across time points may vary. Δ, change from baseline; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed model for repeated measures; N, number of evaluable patients; SE, standard error; TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

At week 16, differences with tofacitinib versus placebo were similar in magnitude between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients for BASDAI50 response rates and LS mean change from baseline in BASDAI, BASMI, and BASFI (Figure 3A‐D).

Response rates and efficacy improvements were generally sustained with tofacitinib from week 16 up to week 48 across outcomes and subgroups (Figure 3A‐D). From weeks 16 to 48, absolute BASDAI50 response rates and LS mean change from baseline in BASDAI were greater in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients (Figure 3A and 3B). Similar observations were made with LS mean change from baseline in BASMI (weeks 40‐48) and BASFI (weeks 16‐32; Figure 3C and 3D).

At week 16, LS mean changes from baseline in ASQoL, patient global assessment, morning stiffness, and SF‐36v2 PCS were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in bDMARD‐naive patients (Supplementary Figure 1A‐D). For TNFi‐IR patients, LS mean changes from baseline were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo for patient global assessment and morning stiffness only (Supplementary Figure 1B and 1C). LS mean changes from baseline in SF‐36v2 MCS were similar between tofacitinib and placebo for both subgroups (Supplementary Figure 1E).

At week 16, differences with tofacitinib versus placebo for LS mean change from baseline in ASQoL, patient global assessment, morning stiffness, SF‐36v2 PCS, and SF‐36v2 MCS were similar in magnitude for bDMARD‐naive patients versus TNFi‐IR patients (Supplementary Figure 1A‐E).

Improvements were generally maintained from week 16 up to week 48 across outcomes and subgroups (Supplementary Figure 1A‐E). From week 16 to 48, greater absolute responses with tofacitinib were observed in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients for LS mean change from baseline in ASQoL and morning stiffness (Supplementary Figure 1A and 1C). Similar observations were made with patient global assessment (weeks 16‐40) and SF‐36v2 PCS (week 16 only; Supplementary Figure 1B and 1D). LS mean changes from baseline in SF‐36v2 MCS were similar between subgroups (Supplementary Figure 1E).

At week 16, LS mean changes from baseline in total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Supplementary Figure 2D and 2E). LS mean changes from baseline in FACIT‐F total, experience domain, and impact domain scores were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in bDMARD‐naive patients only (Supplementary Figure 2A‐C). For LS mean changes from baseline in EQ‐5D‐3L outcomes, including mobility and pain/discomfort, and EQ‐VAS, improvements were greater for tofacitinib versus placebo in bDMARD‐naive patients only (Supplementary Figure 3A, 3D, and 3F). LS mean changes from baseline in EQ‐5D‐3L self‐care, usual activities, and anxiety/depression were similar between tofacitinib and placebo in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients (Supplementary Figure 3B‐C and 3E).

At week 16, differences with tofacitinib versus placebo for LS mean change from baseline in FACIT‐F total score, experience domain, and impact domain, and total back pain and nocturnal spinal pain, were similar in magnitude in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients (Supplementary Figure 2A‐E). Similar observations were made at week 16 for LS mean change from baseline in EQ‐5D‐3L outcomes (mobility, self‐care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and EQ‐VAS (Supplementary Figure 3A‐F).

Improvements were generally sustained from week 16 up to week 48 (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). LS mean change from baseline in FACIT‐F impact domain (weeks 24‐48), total back pain (weeks 16‐32), nocturnal spinal pain (weeks 16‐48), and EQ‐5D‐3L mobility (week 16), self‐care (week 48), and anxiety/depression (week 48), were greater in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐IR patients (Supplementary Figures 2C‐E, 3A, 3B, and 3E). Improvements in FACIT‐F total score, FACIT‐F experience domain, EQ‐5D‐3L usual activities and pain/discomfort, and EQ‐VAS were generally similar between subgroups (Supplementary Figures 2A, 2B, 3C, 3D, and 3F).

Safety

Overall, up to week 16, the proportion of patients who experienced AEs, SAEs, severe AEs, and discontinuation of study drug and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs was generally numerically higher with tofacitinib versus placebo, regardless of prior bDMARD use; this was seen up to week 48 versus placebo switched to tofacitinib (Table 2). There were no deaths. Most frequent AEs across subgroups are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Treatment‐emergent AEs by prior bDMARD use

| bDMARD‐naive patients | TNFi‐IR patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to week 16 | Up to week 48 | Up to week 16 | Up to week 48 | |||||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 102) | Placebo (N = 105) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 102) | Placebo ➔ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 105) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | Placebo (N = 31) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | Placebo ➔ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | |

| AEs, n (%) | 53 (52.0) | 53 (50.5) | 79 (77.5) | 70 (66.7) | 20 (64.5) | 17 (54.8) | 24 (77.4) | 23 (74.2) |

| SAEs, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Severe AEs, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 3 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (9.7) | 0 |

| Deaths, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinuation from study due to AEs a , n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 |

| Discontinuation of study drug due to AEs b , n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (3.9) | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) |

| Dose reduction or temporary discontinuation due to AEs, n (%) | 6 (5.9) | 2 (1.9) | 12 (11.8) | 8 (7.6) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (19.4) | 5 (16.1) |

Note: Data are n (%). MedDRA v23.0 coding dictionary applied. Patients randomized to receive placebo were switched to open‐label tofacitinib 5 mg BID at week 16.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; N, number of patients in safety analysis set; n, number of patients experiencing specific event; SAE, serious AE (based on clinical database); TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

Patients with an AE record that indicated that the AE caused the patient to be discontinued from the study.

Patients with an AE record that indicated that the study treatment was drug was withdrawn.

Table 3.

Most frequent treatment‐emergent AEs and laboratory investigations (>5% in any subgroup) by prior bDMARD use

| bDMARD‐naive patients | TNFi‐IR patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up to week 16 | Up to week 48 | Up to week 16 | Up to week 48 | |||||

| Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 102) | Placebo (N = 105) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 102) | Placebo ➔ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 105) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | Placebo (N = 31) | Tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | Placebo ➔ tofacitinib 5 mg BID (N = 31) | |

| Nasopharyngitis, n (%) | 8 (7.8) | 9 (8.6) | 10 (9.8) | 16 (15.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Pharyngitis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) |

| Oropharyngeal pain, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 2 (6.5) | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection, n (%) | 9 (8.8) | 5 (4.8) | 15 (14.7) | 10 (9.5) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | 6 (19.4) | 8 (25.8) |

| Urinary tract infection, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 2 (6.5) |

| Abdominal pain, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) |

| Upper abdominal pain, n (%) | 0 | 4 (3.8) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) |

| Epigastric discomfort, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0 |

| Diarrhea, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 2 (1.9) | 6 (5.9) | 5 (4.8) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) |

| Arthralgia, n (%) | 0 | 5 (4.8) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.7) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) |

| Arthritis, n (%) | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) |

| Costochondritis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0 |

| Headache, n (%) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.9) | 4 (3.9) | 6 (5.7) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) |

| Dizziness, n (%) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) |

| Neck pain, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (9.7) | 0 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.9) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) |

| Thermal burn, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0 | 2 (6.5) |

| Blood pressure, increased, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 0 |

| Weight, increased, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 4 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) |

| Abnormal hepatic function, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 2 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) |

| Alanine aminotransferase, increased, n (%) | 3 (2.9) | 1 (1.0) | 7 (6.9) | 2 (1.9) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 0 |

| Protein urine, present, n (%) | 4 (3.9) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (5.9) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (9.7) |

| Transaminase, increased, n (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (9.7) | 0 |

Note: Data are n (%). MedDRA v23.0 coding dictionary applied. Patients randomized to receive placebo were switched to open‐label tofacitinib 5 mg BID at week 16.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; bDMARD, biologic disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; BID, twice daily; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; N, number of patients in safety analysis set; n, number of patients experiencing specific event; TNFi‐IR, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor‐inadequate responder.

Up to week 16, the proportion of patients who experienced AEs, and discontinuation of study drug and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs, was numerically higher for the TNFi‐IR subgroup compared with the bDMARD‐naive subgroup receiving tofacitinib or placebo (Table 2).

Up to week 48, the proportion of patients who experienced discontinuation of study/study drug and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs was numerically higher for the TNFi‐IR subgroup compared with the bDMARD‐naive subgroup receiving tofacitinib; AEs were consistent between subgroups (Table 2). Rates of AEs, SAEs, and discontinuation of study drug and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs were generally numerically higher for the TNFi‐IR subgroup compared with the bDMARD‐naive subgroup receiving placebo who switched to tofacitinib (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Although the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for the treatment of AS have been demonstrated in a phase 3 clinical trial (8), the impact of treatment history on response to tofacitinib has not been fully described. This post hoc analysis used data from the phase 3 clinical trial to evaluate the impact of prior bDMARD treatment (bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients) on tofacitinib efficacy and safety. Given that treatment guidelines recommend tofacitinib in patients with active AS who are TNFi‐IR or are intolerant to TNFi (depending on location) (5, 6, 9, 16), assessing tofacitinib in these stratified populations is of clinical importance.

Overall, tofacitinib generally demonstrated greater efficacy versus placebo at week 16 in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients; exceptions were noted in the TNFi‐IR subgroup in which a numerical difference was observed (95% CIs of the treatment differences of tofacitinib vs. placebo included zero), including ASAS partial remission and ASDAS inactive disease responses, and LS mean change from baseline in BASFI, ASQoL, SF‐36v2 PCS, FACIT‐F (total, experience domain, and impact domain scores), EQ‐5D‐3L (mobility and pain/discomfort), and EQ‐VAS. It is important to note the small sample size, particularly in the TNFi‐IR group; therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. Efficacy was maintained from week 16 up to week 48 in both subgroups. At week 16, across multiple disease activity outcomes and patient‐reported outcomes, differences in improvements observed with tofacitinib versus placebo were similar in magnitude in the bDMARD‐naive versus the TNFi‐IR subgroup. From weeks 4 to 48, across outcomes and at certain time points (outcomes including ASAS20, ASAS40, ASAS 5/6, ASDAS CRP major improvement, LS mean change from baseline in ASDAS, ASAS partial remission, ASDAS CRP clinically important improvement, and inactive disease response rates), differences in absolute responses were observed between subgroups. The absolute magnitude of responses was generally greater in bDMARD‐naive patients versus TNFi‐IR patients. Overall, a numerically higher proportion of patients receiving tofacitinib versus placebo experienced safety events. In patients who received tofacitinib through week 48, the proportion who experienced AEs was similar between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients. However, discontinuation due to AEs was numerically higher for the TNFi‐IR subgroup compared with the bDMARD‐naive subgroup.

The findings of this analysis were in line with the recently published analysis of data from two phase 3 studies (COAST‐V and COAST‐W) comparing ixekizumab treatment in bDMARD‐naive patients and TNFi‐experienced patients with AS, in whom it was shown that ixekizumab was efficacious in both patient groups after 16 weeks and up to 52 weeks of treatment (10). Here, differences in improvements versus placebo were generally similar between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients. Interestingly, in the analysis of COAST‐V and COAST‐W, responses with ixekizumab tended to be numerically greater in bDMARD‐naive versus TNFi‐experienced patients (10). Similarly, in patients with AS receiving secukinumab in the MEASURE‐2 phase 3 trial, TNFi‐naive patients were shown to have significantly greater ASAS20 responses versus placebo at 16 weeks compared with TNFi‐IR patients (11). Reduced clinical responses have also been observed in bDMARD‐IR versus bDMARD‐naive patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving tofacitinib or bDMARD therapy (17, 18). However, a cross‐trial comparison has shown that clinical responses to upadacitinib were consistent between bDMARD‐naive and bDMARD‐IR patients with AS (14, 15). Taken together, these results suggest that tofacitinib and IL‐17 therapy are efficacious in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐experienced patients with AS. However, those previously treated with a bDMARD could represent a more difficult‐to‐treat population than bDMARD‐naive patients, an observation that requires further investigation.

To week 48, regardless of prior treatment, a numerically higher proportion of AEs, discontinuation of study drug, and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs occurred in the tofacitinib treatment group than in the placebo group, similar to the overall population in the tofacitinib phase 3 trial (8). In addition, there were no deaths, and no cases of adjudicated major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), malignancies (including non‐melanoma skin cancer [NMSC]), thromboembolic events, opportunistic infections, interstitial lung disease, or gastrointestinal perforations reported in the overall population (8).

Long‐term data are lacking for tofacitinib in AS. ORAL Surveillance, a large, randomized, postauthorization safety study of tofacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 50 years of age or older with one or more cardiovascular risk factors, evaluated the risk of adjudicated MACE and malignancies (excluding NMSC) with tofacitinib versus TNFi (19). Noninferiority was not shown for either adjudicated MACE or malignancies (excluding NMSC) for tofacitinib (5 and 10 mg BID combined) versus TNFi, and the risk of MACE and malignancies was increased with tofacitinib versus TNFi in these patients. The study also identified an increased frequency of pulmonary embolism in patients receiving tofacitinib 10 mg BID versus 5 mg BID and TNFi, and an increase in overall mortality with tofacitinib 10 mg BID versus TNFi (19).

To week 16, the proportion of bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients who experienced SAEs was numerically higher with tofacitinib versus placebo, consistent with the results of an integrated safety analysis of pooled data of phase 2 and phase 3 trials in patients with AS who received tofacitinib (20). Here, in those who received tofacitinib through to week 48, a similar proportion of bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients experienced an AE. In the analysis of COAST‐V and COAST‐W, a numerically higher proportion of TNFi‐experienced patients receiving ixekizumab experienced an AE (weeks 16‐52) compared with bDMARD‐naive patients (10). Furthermore, in this study, a numerically higher proportion of TNFi‐IR patients versus bDMARD‐naive patients experienced discontinuation of study drug and dose reduction/temporary discontinuation due to AEs. As the TNFi‐IR subgroup included patients who were intolerant to TNFi due to AEs, patients in this subgroup may be more likely to experience AEs. Similar observations were made for discontinuation due to AEs for TNFi‐experienced versus bDMARD‐naive patients receiving ixekizumab (10). Although the follow‐up length in this study was relatively short to assess long‐term safety with tofacitinib in patients with AS, these data could indicate that prior bDMARD treatment history may have an impact on safety outcomes.

This study can be discussed in the context of some limitations. This analysis was post hoc in nature and relatively short in duration for the assessment of long‐term efficacy and safety in these patient groups. The overall sample size was low, particularly in the TNFi‐IR subgroup, and results should be interpreted with caution. The study was not powered to detect treatment differences within any of the subgroups nor to assess similarity in treatment effects between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR subgroups. Definitions of “greater” and “numerically greater,” with respect to treatment differences, did not indicate statistical significance, and a larger sample size may or may not affect these results. There were some imbalances in baseline characteristics between subgroups, such as BMI and disease duration. In addition, the overall safety analysis was limited in scope. Lastly, the primary study did not include patients with nonradiographic axSpA; therefore, the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in this patient population is not well characterized.

In conclusion, tofacitinib generally demonstrated greater efficacy versus placebo for both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients with AS at week 16, with some exceptions in the TNFi‐IR subgroup, with responses sustained up to week 48. Differences in improvements observed with tofacitinib versus placebo were generally of a similar magnitude between bDMARD‐naive and the TNFi‐IR subgroup. At baseline, TNFi‐IR patients had higher BMI and longer disease duration versus bDMARD‐naive patients. In patients who received tofacitinib through week 48, the proportion of patients who experienced AEs was similar between bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients. However, discontinuation of study drug due to AEs was numerically higher for the TNFi‐IR subgroup compared with the bDMARD‐naive subgroup. This analysis found that the benefit–risk balance for tofacitinib treatment was favorable in both bDMARD‐naive and TNFi‐IR patients with AS; however, it may be more favorable in bDMARD‐naive patients in part driven by greater efficacy. This analysis was limited by the small sample size overall and differences in sample size between subgroups; therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. Real‐world and longer‐term data are required to fully understand the effectiveness and tolerability of tofacitinib in patients with AS.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Deodhar, Wu, Wang, Dina, Kanik, Fallon, Gensler.

Acquisition of data

Deodhar, Wu, Wang, Dina, Kanik, Gensler.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Deodhar, Marzo‐Ortega, Wu, Wang, Dina, Kanik, Fallon, Gensler.

ROLE OF STUDY SPONSOR

This study was sponsored by Pfizer. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. The authors did not receive payment for development of this article. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lewis C. Rodgers, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 1298–304). Authors from Pfizer were involved in the study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript, and approved the content of the submitted manuscript. Pfizer was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as well as intellectual property considerations.

Supporting information

Disclosure Form:

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Marzo‐Ortega is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health. This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lewis C. Rodgers, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 1298–304).

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03502616.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), or the UK Department of Health.

Supported by Pfizer. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Lewis C. Rodgers, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications, and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1298–304). Dr. Marzo‐Ortega's work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Leeds Biomedical Research Centre.

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions, and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual deidentified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Author disclosures are available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr2.11601.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boel A, Molto A, van der Heijde D, et al. Do patients with axial spondyloarthritis with radiographic sacroiliitis fulfil both the modified New York criteria and the ASAS axial spondyloarthritis criteria? Results from eight cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:1545–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mease P, Deodhar A. Differentiating nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis from its mimics: a narrative review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2022;23:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sieper J, Braun J, Rudwaleit M, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: an overview. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61 Suppl 3:iii8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross‐sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:905–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, et al. 2019 Update of the American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and non‐radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71:1285–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ramiro S, Nikiphorou E, Sepriano A, et al. ASAS‐EULAR recommendations for the management of axial spondyloarthritis: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing pondylitis: a phase II, 16‐week, randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1340–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deodhar A, Sliwinska‐Stanczyk P, Xu H, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: a phase III, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:1004–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Inc Pfizer. U.S. FDA approves Pfizer's XELJANZ® (tofacitinib) for the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis. 2021. URL: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/us-fda-approves-pfizers-xeljanzr-tofacitinib-treatment-0.

- 10. Dougados M, Wei JC, Landewé R, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab through 52 weeks in two phase 3, randomised, controlled clinical trials in patients with active radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (COAST‐V and COAST‐W). Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:176–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo‐Ortega H, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in anti‐TNF‐naive and anti‐TNF‐experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:571–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van der Heijde D, Cheng‐Chung Wei J, Dougados M, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin‐17A antagonist in the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis or radiographic axial spondyloarthritis in patients previously untreated with biological disease‐modifying anti‐rheumatic drugs (COAST‐V): 16 week results of a phase 3 randomised, double‐blind, active‐controlled and placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:2441–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deodhar A, Poddubnyy D, Pacheco‐Tena C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in the treatment of radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: sixteen‐week results from a phase III randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial in patients with prior inadequate response to or intolerance of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:599–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Sieper J, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib for active ankylosing spondylitis refractory to biological therapy: a double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:1515–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van der Heijde D, Song IH, Pangan AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT‐AXIS 1): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019;394:2108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Food and Drug Administration . XELJANZ® (tofacitinib): highlights of prescribing information. 2022. URL: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=959.

- 17. Charles‐Schoeman C, Burmester G, Nash P, et al. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib following inadequate response to conventional synthetic or biological disease‐modifying antirheumatic drugs. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rendas‐Baum R, Wallenstein GV, Koncz T, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of sequential biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis patients with an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor‐a inhibitors. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13:R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2022;386:316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deodhar A, Akar S, Curtis J, et al. Integrated safety analysis of tofacitinib in ankylosing spondylitis clinical trials [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:POS0296. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Disclosure Form:

Appendix S1: Supporting Information