Abstract

The study described herein aimed to examine changes in HDAC4 and its downstream targets in immobilization-induced rat skeletal muscle atrophy. Eleven male Wistar rats were used, and one hindlimb was immobilized in the plantar flexion position using a plaster cast. The contralateral, non-immobilized leg served as an internal control. After 10 days, the gastrocnemius muscles were removed from both hindlimbs. Ten days of immobilization resulted in a significant reduction (−27.3 %) in gastrocnemius muscle weight. A significant decrease in AMPK phosphorylation was also observed in nuclear fractions from immobilized legs relative to the controls. HDAC4 expression was significantly increased in immobilized legs in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Moreover, Myogenin and MyoD mRNA levels were upregulated in immobilized legs, resulting in increased Atrogin-1 mRNA expression. Our data suggest that nuclear HDAC4 accumulation is partly related to immobilization-induced muscle atrophy.

Keywords: Disuse muscle atrophy, Histone deacetylase 4, Myogenic regulatory factors, Nuclear abundance

Introduction

Prolonged periods of muscle disuse due to immobilization, chronic bed rest, physical inactivity, or spaceflight can result in a significant decrease in the cross-sectional area of individual myofibers [1]. Skeletal muscle wasting induced by limb immobilization causes muscle atrophy via multiple signaling pathways [2, 3], but the molecular mechanisms are not completely understood.

Recently, protein acetylation was recognized as an important form of post-transcriptional modification, regulated by both histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (HDACs). HDACs are classified as class I (HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8), class IIa (HDACs 4, 5, 7, and 9), class IIb (HDACs 6 and 10), class III HDACs [sirtuins (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog) 1–7], and class IV (HDAC 11) [4]. In skeletal muscle, HDACs are well known for regulating muscle proliferation, differentiation, and growth through regulation of histone acetylation, which leads to transcriptional activation and repression [5]. In particular, class IIa HDACs were shown to play important roles in the maintenance of muscle mass and protein degradation during muscle wasting [6–9].

The protein deacetylase HDAC4 has attracted much attention as a central component of muscle transcriptional reprogramming upon denervation. Moresi et al. and other investigators have demonstrated that class II HDACs (HDAC4 and 5), as well as the transcriptional muscle regulator Myogenin and downstream E3 ligases, control muscle atrophy following denervation [8–10]. These data suggest that HDAC4 plays an important role in other muscle wasting models; however, whether HDAC4 is associated with disuse muscle atrophy remains unclear. Additionally, HDAC4 shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus, where it acts as a transcriptional repressor [11]. In fact, nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 promotes neurodegeneration in ataxia telangiectasia [12]. Therefore, cellular localization of HDAC4 is crucial for the events leading to muscular atrophy. Thus, this study examined changes in nuclear HDAC4 expression and its downstream targets in immobilization-induced rat skeletal muscle atrophy.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

This study was approved by the Juntendo University Animal Care Committee (H20-02) and followed the guiding principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals set forth by the Physiological Society of Japan. Seventeen male Wistar rats (9 weeks old) were used in this study. All rats were housed in a climate-controlled room (24 ± 1 °C, 55 ± 5 % relative humidity, 12:12-h light–dark photoperiod) and given access to standard rat chow and water ad libitum.

Unilateral immobilization

The rats were randomly assigned to two groups: age-matched, non-immobilized rats (controls, n = 6) and hindlimb-immobilized rats (n = 11). The rats in the immobilization group were first anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). One hindlimb was immobilized (Imm) in the plantar flexion position with a Toxicon addition type heavy (Sankin Industry Co., Ltd.). The contralateral, non-immobilized leg served as an internal control (Con). The animals were monitored on a daily basis for chewed plaster, abrasions and problems with ambulation. Animals were allowed to move, eat and drink ad libitum. The immobilization procedure prevented movement of the immobilized leg alone. After 10 days, animals were sacrificed and gastrocnemius muscles were removed from both hindlimbs. Muscles were stored at −80 °C until further processed.

Muscle preparation

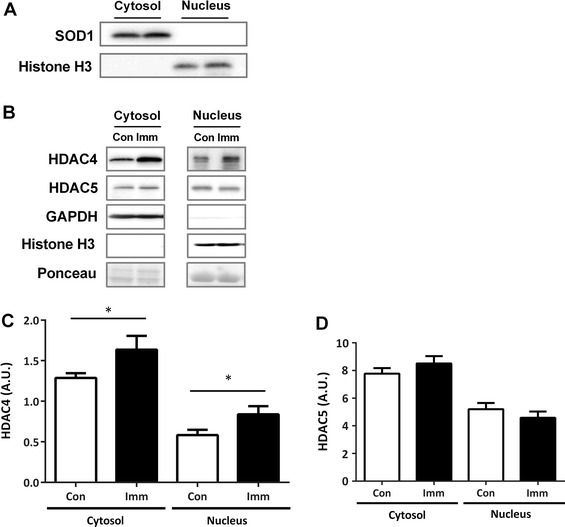

Frozen gastrocnemius muscles were powdered, and a portion of the muscles (~100 mg) was homogenized in 10 volumes of ice-cold homogenization buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 4 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 % Triton X-100) containing Complete EDTA-free (Roche, Penzberg, Germany) and PhosSTOP (Roche) protease inhibitor cocktails. Homogenates were centrifuged at 900 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to collect nuclear pellets according to the method of Senf et al. [13]. Supernatants were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to collect cytosolic fractions. Nuclear pellets were subsequently washed three times via resuspension in homogenization buffer and centrifugation at 900 × g, followed by rotation at 4 °C for 2 h in 10 volumes of ice-cold NaCl buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 2.5 M NaCl, 4 mM EGTA, 10 mM EDTA, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 % Triton X-100) containing Complete EDTA-free and PhosSTOP. Samples were then centrifuged at 21,100 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and supernatants saved as nuclear protein fractions. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA). Successful cytosolic and nuclear separation was confirmed by Western blotting for Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD1) and histone-H3 (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

HDAC4 and HDAC5 levels after 10 days of hindlimb immobilization. Cellular fractionation of proteins (a). Using specific probes, we examined the expression of nuclear Histone H3 or cytosolic SOD1. Representative blots of (b) HDAC4 (c) and HDAC5 (d) in cytosolic (cytosol) and nuclear (nucleus) fractions. Equal protein loading was confirmed by Ponceau S staining, and by GAPDH and Histone H3 immunodetection. Con, n = 11 (white bar); Imm, n = 11 (black bar). All data are expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 versus Con

Immunoblotting

Proteins were loaded onto 7.5–15 % sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and run at 150–200 V for 45–75 min. Separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), blocked with 5 % nonfat dry milk, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the following primary antibodies: phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (1:2000; Cell Signaling, #2531, Beverly, MA, USA), AMPKα (1:2000; Cell Signaling, #2532), HDAC4 (1:2000; Cell Signaling, #7628), HDAC5 (1:2000; Cell Signaling, #2082), Histone H3 (1:2000; Millipore, #06-755), and Cu/Zn SOD (1:2000; Assay Designs, SOD-100, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:3000; Cell Signaling, #7074) for 1 h at room temperature. Proteins were detected using ECL Prime reagent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA), and signals recorded with an ATTO Light Capture system (Tokyo, Japan). Analyses were performed using CS ANALYZER 3.0 software (ATTO). GAPDH immune detection (cytosol), histone H3 immune detection (nucleus), and Ponceau red staining were used as loading controls to confirm standardized protein loading and transfer.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA isolation was performed according to the method of Okamoto et al. [14]. RNA was purified using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74104), and concentration and purity (A260/280 and A260/230) were determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, CA, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with an input of 2-μg total RNA using SuperScript VILO MasterMix (Invitrogen). The mRNA expression of Myogenin (Rn01490689_g1, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), MyoD (Rn01457527_g1), Atrogin-1/MAFbx (Rn00591730_m1), and MuRF1 (Rn00590197_m1) was quantified by TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μl, which included 10 μl of TaqMan Universal Master Mix II (Applied Biosystems), 1 μl of TaqMan primer and probe mix, and 9 μl of cDNA. The PCR conditions used were as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, then 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min, with a final cycle at 37 °C for 30 s in a LightCycler 480 System II (Roche). mRNA concentrations were normalized to 18S mRNA levels, and the 2−ΔΔCt method was utilized for data analysis: Ct = Ct (gene of interest) − Ct (reference gene), where threshold cycle (CT) indicates the fractional cycle number at which the amount of amplified target reached a fixed threshold. Relative change in expression levels of one specific gene (ΔΔCt) was calculated by subtracting the ΔCt of the un-immobilized control leg.

Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) composition

To determine fiber-type alterations, MyHC composition was determined using modified methods of Sugiura and Murakami [15] described previously [16]. Each gel was scanned using a calibrated densitometer (GS800, Bio-Rad) and analyzed by Quantity one (Bio-Rad) to assess the relative percentages of MyHC isoforms.

Statistical analyses

Values are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using the Prism v. 6.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

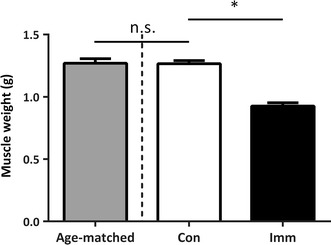

Muscle wet weight

After 10 days, gastrocnemius muscles were removed from both the immobilized and contralateral leg (internal control), as well as age-matched control rats, which were not subjected to immobilization (Fig. 1). Ten days of hindlimb immobilization resulted in a significant reduction in gastrocnemius muscle weight (−27.3 %) from the immobilized leg compared with the control leg (Con, 1.26 ± 0.04 g; Imm, 0.89 ± 0.04 g; p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in gastrocnemius muscle weight between age-matched control rats and Con (p > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Muscle weight in the gastrocnemius muscle after 10 days hindlimb immobilization. Con, n = 11 (white bar); Imm, n = 11 (black bar); age-matched, non-immobilized rats, n = 6 (gray bar). The data are expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 versus Con

HDAC4 and HDAC5 expression

HDAC4 expression was significantly increased in immobilized legs in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions (Fig. 2b, c), whereas no significant difference in HDAC5 expression was detected in either the cytoplasmic or nuclear fractions (Fig. 2b, d).

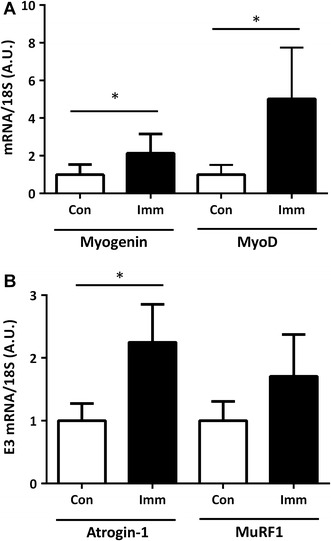

Downstream targets of HDAC4

To assess potential alternations in the downstream targets of HDAC4, the mRNA and protein expression of two members of a family of myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), Myogenin and MyoD, and of the E3 ligases Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 was determined. Myogenin and MyoD mRNA levels were elevated 5.0- and 2.3-fold in immobilized legs (Fig. 3a). Although no change in MuRF1 mRNA expression was detected, Atrogin-1 mRNA expression was elevated 2.2-fold in immobilized legs (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Myogenin and MyoD (a) and E3 ubiquitin ligase (Atrogin-1 and MuRF1) (b) mRNA expression. The mRNA expression of Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 was normalized to that of 18S mRNA to demonstrate that changes in target gene/housekeeping gene ratios were independent of changes in a specific housekeeping gene. Con, n = 11 (white bar); Imm, n = 11 (black bar). Data are expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 versus Con

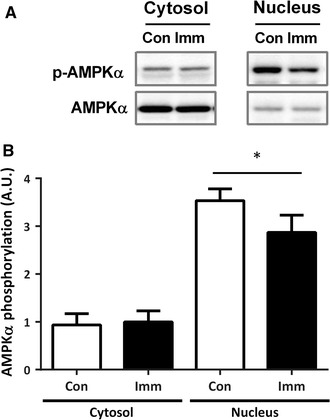

Phospho-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)α expression

In the cytoplasmic fractions, there was no change in AMPKα phosphorylation between the control and immobilized legs (Fig. 4a, b). Alternatively, a significant decrease in the phosphorylation ratio of AMPKα was observed in the nuclear fractions from the immobilized legs relative to those from the controls.

Fig. 4.

AMPK phosphorylation after 10 days of hindlimb immobilization. Representative blots (a) of phospho- and total-AMPKα, and the phosphorylation ratio of AMPKα (b) in cytosolic (cytosol) and nuclear (nucleus) fractions. Con, n = 11 (white bar); Imm, n = 11 (black bar). All data are expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 versus Con

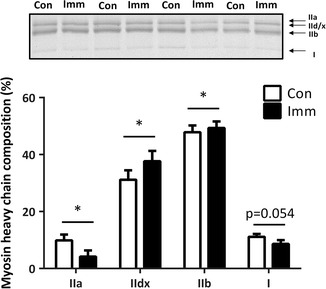

Myosin heavy chain composition

Figure 5 summarizes alterations in MyHC in both the control and immobilized legs. Hindlimb immobilization significantly increased type IId/x and type IIb MyHC isoforms and significantly decreased type IIa MyHC isoforms. In addition, the type I MyHC isoform showed a trend towards a decrease in immobilized legs compared with the controls (p = 0.054).

Fig. 5.

Myosin heavy chain isoforms in the gastrocnemius muscle after 10 days of hindlimb immobilization. Con, n = 11 (white bar); Imm, n = 11 (black bar). Data are expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 versus Con

Discussion

Overview of principal findings

This study provides new and important information; our results strongly suggest that the nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 and downstream genes may play an important role in immobilization-induced rat skeletal muscle atrophy. Nuclear abundance of HDAC4 promotes Myogenin and MyoD mRNA expression and activates subsequent Atrogin-1 expression, a central component of muscle atrophy.

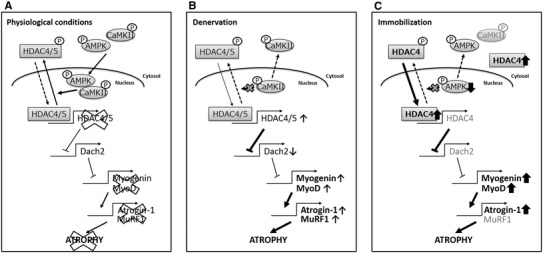

Immobilization-induced muscle atrophy increases nuclear HDAC4 and its target genes

Previous studies have demonstrated that class II HDACs, such as HDAC4 and 5, regulate neurogenic muscle atrophy [9] (Fig. 6b). However, it is unknown as to whether HDAC4 regulates immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Under normal physiological conditions, HDAC4 and 5 shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus, where they act as transcriptional repressors (Fig. 6a). Although alterations in HDAC5 levels were not observed in the current study, the nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 was increased in immobilized legs. As in denervation, nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 led to the upregulation of Myogenin and MyoD mRNA expression in immobilized muscles (Fig. 6c) [8–10]. Myogenin and MyoD are myogenic differentiation factors that activate atrogin-1- and MuRF1-induced protein degradation [17]. Indeed, we found that Atrogin-1 mRNA was increased 2.2-fold in hindlimb muscles after 10 days of immobilization. Our data are in agreement with those of previous studies using denervation and spinal muscular atrophy models [7–10]. For example, HDAC4 represses the expression of Dach2, a negative regulator of Myogenin, thereby activating the expression of E3 ligases that participate in the proteolytic pathway, resulting in neurogenic muscle atrophy [9]. Moreover, HDAC inhibitors block the expression of Myogenin in response to denervation, and HDAC4 knockout mice exhibit protection against neurogenic muscle atrophy induced by denervation [9]. These data indicate that HDAC4-mediated Myogenin and/or MyoD upregulation is a common phenomenon among immobilization, denervation, cancer, and other diseases [7, 9, 10, 12, 18]. HDAC5 expression was unchanged in the present study, in contrast to denervation-induced muscular atrophy. However, Tang et al. [19] reported that muscle denervation did not change HDAC5 expression in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle; therefore, HDAC5 may not play a key role in skeletal muscle atrophy. Moreover, we did not observe a significant increase in MuRF1 mRNA in atrophied gastrocnemius muscle tissue; it was not detected at the time of the peak in the present study (3 days after immobilization) [20].

Fig. 6.

HDAC4-mediated regulation of disuse muscle atrophy-related gene expression. a Normal physiological conditions. b Denervation-induced catabolic conditions. c Immobilization-induced catabolic conditions. Disuse induced the nuclear accumulation of HDAC4, upregulation of Myogenin and MyoD, and subsequent E3 ligase expression. Bold arrows represent increased or decreased expression

Our data indicate that the nuclear abundance of HDAC4 plays an important role in immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy, given that the overexpression of HDAC4 exacerbates denervation-induced muscle atrophy [21]. Unfortunately, the contribution of HDAC4 to the upregulation of atrophic E3 ligases remains unclear. E3 ligases are regulated by other transcription factors, including forkhead box subfamily O transcription factors [3]; therefore, additional studies are required to elucidate the contribution of nuclear HDAC4 accumulation to E3 ligase upregulation in immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy.

Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 were not examined in the present study, we showed nuclear deactivation of AMPKα, which can induce the nuclear export of HDAC4 [22]. In relation to exercise adaptation, AMPKα is an important kinase for HDAC4 and 5; it increases in nuclear abundance [23] and is activated in human skeletal muscle following a bout of exercise, resulting in the upregulation of metabolic genes, such as glucose transporter genes [24]. In contrast, disuse conditions, such as limb immobilization, decrease both the energy status of muscles [25] and nuclear AMPKα phosphorylation in atrophied muscle. These data indicate that hindlimb immobilization induces AMPKα deactivation in the nucleus and subsequent nuclear accumulation of HDAC4, resulting in upregulation of atrophy-related gene expression. In contrast, in denervation-induced muscle atrophy, calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) II is a prime candidate for mediating HDAC nuclear export [8, 19]. This suggests the existence of different underlying mechanisms between disuse- and denervation-induced muscle atrophy; however, the precise mechanisms controlling the nuclear abundance of HDAC4 remain unclear.

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating a nuclear abundance of HDAC4 in immobilized rat skeletal muscle. Our data indicate that HDAC4 plays an important role in immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Contrary to our observations, HDAC4 was downregulated in atrophied human vastus lateralis muscle after 10 days of bed rest [26]. In this regard, Tang et al. [19] showed that HDAC4 is enriched in TA muscle small oxidative IIa fibers and contributes to denervation-induced IIa type shift by suppressing the expression of fast MyHC IIb. In contrast, Potthoff et al. [27] demonstrated in mice that class II HDACs (HDAC4, -5, and -7) were preferentially expressed in fast-fiber dominant plantaris (PLA), extensor digitorum longus (EDL), and superficial white vastus lateralis (WV) muscles, with relatively little expression in the slow-fiber enriched soleus muscle. Transgenic mouse models were also used to determine whether fast- to slow-fiber transformation correlated with a downregulation of class II HDACs. As a result, the transformation of WV muscles towards a slow myofiber was associated with diminished expression of class II HDAC proteins (HDAC4, -5 and -7) [27]. These data indicate the possibility that class II HDACs repress the expression of slow-fiber genes in fast myofibers. In our study, immobilization-induced muscle atrophy caused a slow-to-fast MyHC-type shift as described previously [28], and HDAC4 expression was increased in atrophied gastrocnemius muscles. This contradiction may be caused by differences in fiber type composition, cellular localization of HDAC4, muscle atrophy ratio, and the species being examined. Further study is required to assess fiber-specific changes in HDAC4 expression following disuse muscle atrophy.

Conclusions

In summary, nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 and the upregulation of Myogenin and MyoD expression are induced by immobilization in rat skeletal muscle. Nuclear HDAC4 accumulation is partly related to immobilization-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Additional studies are necessary to reveal whether the therapeutic inhibition of HDAC4 can ameliorate the progression of muscle atrophy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant No. 26506021 (T. Yoshihara). Grants from the MEXT-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities also supported this research.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Boonyarom O, Inui K. Atrophy and hypertrophy of skeletal muscles: structural and functional aspects. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2006;188(2):77–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elliott B, Renshaw D, Getting S, Mackenzie R. The central role of myostatin in skeletal muscle and whole body homeostasis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2012;205(3):324–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2012.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaldo P, Sandri M. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of muscle atrophy. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6(1):25–39. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda H, Sano N, Muto S, Horikoshi M. Simple histone acetylation plays a complex role in the regulation of gene expression. Brief Funct Genom Proteom. 2006;5(3):190–208. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGee SL, Hargreaves M. Histone modifications and exercise adaptations. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2011;110(1):258–263. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00979.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alamdari N, Aversa Z, Castillero E, Hasselgren PO. Acetylation and deacetylation—novel factors in muscle wasting. Metabolism. 2013;62(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi MC, Cohen TJ, Barrientos T, Wang B, Li M, Simmons BJ, Yang JS, Cox GA, Zhao Y, Yao TP. A direct HDAC4-MAP kinase crosstalk activates muscle atrophy program. Mol Cell. 2012;47(1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen TJ, Waddell DS, Barrientos T, Lu Z, Feng G, Cox GA, Bodine SC, Yao TP. The histone deacetylase HDAC4 connects neural activity to muscle transcriptional reprogramming. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(46):33752–33759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moresi V, Williams AH, Meadows E, Flynn JM, Potthoff MJ, McAnally J, Shelton JM, Backs J, Klein WH, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Myogenin and class II HDACs control neurogenic muscle atrophy by inducing E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cell. 2010;143(1):35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bricceno KV, Sampognaro PJ, Van Meerbeke JP, Sumner CJ, Fischbeck KH, Burnett BG. Histone deacetylase inhibition suppresses myogenin-dependent atrogene activation in spinal muscular atrophy mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(20):4448–4459. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGee SL, van Denderen BJ, Howlett KF, Mollica J, Schertzer JD, Kemp BE, Hargreaves M. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates GLUT4 transcription by phosphorylating histone deacetylase 5. Diabetes. 2008;57(4):860–867. doi: 10.2337/db07-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Chen J, Ricupero CL, Hart RP, Schwartz MS, Kusnecov A, Herrup K. Nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 in ATM deficiency promotes neurodegeneration in ataxia telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):783–790. doi: 10.1038/nm.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senf SM, Dodd SL, Judge AR. FOXO signaling is required for disuse muscle atrophy and is directly regulated by Hsp70. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298(1):C38–C45. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00315.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okamoto T, Torii S, Machida S. Differential gene expression of muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase MAFbx/Atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in response to immobilization-induced atrophy of slow-twitch and fast-twitch muscles. J Physiol Sci. 2011;61(6):537–546. doi: 10.1007/s12576-011-0175-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiura T, Murakami N. Separation of myosin heavy-chain isoforms in rat skeletal-muscles by gradient sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel-electrophoresis. Biomed Res Tokyo. 1990;11(2):87–91. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.11.87. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogura Y, Naito H, Kakigi R, Ichinoseki-Sekine N, Kurosaka M, Yoshihara T, Akema T. Effects of ageing and endurance exercise training on alpha-actinin isoforms in rat plantaris muscle. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;202(4):683–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2011.02284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chopard A, Hillock S, Jasmin BJ. Molecular events and signalling pathways involved in skeletal muscle disuse-induced atrophy and the impact of countermeasures. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9B):3032–3050. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halkidou K, Cook S, Leung HY, Neal DE, Robson CN. Nuclear accumulation of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) coincides with the loss of androgen sensitivity in hormone refractory cancer of the prostate. Eur Urol. 2004;45(3):382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang H, Macpherson P, Marvin M, Meadows E, Klein WH, Yang XJ, Goldman D. A histone deacetylase 4/myogenin positive feedback loop coordinates denervation-dependent gene induction and suppression. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20(4):1120–1131. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baptista IL, Leal ML, Artioli GG, Aoki MS, Fiamoncini J, Turri AO, Curi R, Miyabara EH, Moriscot AS. Leucine attenuates skeletal muscle wasting via inhibition of ubiquitin ligases. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41(6):800–808. doi: 10.1002/mus.21578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bongers KS, Fox DK, Ebert SM, Kunkel SD, Dyle MC, Bullard SA, Dierdorff JM, Adams CM. Skeletal muscle denervation causes skeletal muscle atrophy through a pathway that involves both Gadd45a and HDAC4. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(7):E907–E915. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00380.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGee SL, Sparling D, Olson AL, Hargreaves M. Exercise increases MEF2- and GEF DNA-binding activity in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2006;20(2):348–349. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4671fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGee SL, Howlett KF, Starkie RL, Cameron-Smith D, Kemp BE, Hargreaves M. Exercise increases nuclear AMPK alpha2 in human skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2003;52(4):926–928. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.4.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGee SL, Fairlie E, Garnham AP, Hargreaves M. Exercise-induced histone modifications in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 24):5951–5958. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wall BT, van Loon LJ. Nutritional strategies to attenuate muscle disuse atrophy. Nutr Rev. 2013;71(4):195–208. doi: 10.1111/nure.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezen T, Kovanda A, Eiken O, Mekjavic IB, Rogelj B. Expression changes in human skeletal muscle miRNAs following 10 days of bed rest in young healthy males. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;210(3):655–666. doi: 10.1111/apha.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potthoff MJ, Wu H, Arnold MA, Shelton JM, Backs J, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Histone deacetylase degradation and MEF2 activation promote the formation of slow-twitch myofibers. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(9):2459–2467. doi: 10.1172/JCI31960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aoki MS, Lima WP, Miyabara EH, Gouveia CH, Moriscot AS. Deleterious effects of immobilization upon rat skeletal muscle: role of creatine supplementation. Clin Nutr. 2004;23(5):1176–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]