News magazine US News and World Report began an article aboutthrombolytic treatment of acute stroke with the following anecdote:

One Wednesday morning in January, 36-year-old Laurie Lucas was rushingabout, dressing her daughters for school and talking on the phone, when astrange confusion swept over her. She felt woozy. Her right arm flailed aboutand her right leg went weak. Paramedics arriving at Lucas's Sanford, Florida,home thought she was having epileptic seizures, but brain scans revealed ablockage of an artery that supplies the brain with blood. Lucas, a physicallyfit former professional cheerleader, had suffered a massive stroke... If Lucashad been stricken a year ago, before a new treatment was developed, she almostcertainly would havedied.1(p62)

This story is interesting but misleading. It is not plausible thatphysicians could accurately conclude that Laurie Lucas “almost certainlywould have died” without treatment. Nor is it true that“massive” strokes are likely to benefit from thrombolytictreatment.2 Inaddition to several anecdotes, the US News and World Report articleincludes “expert” testimony in which prominent physiciansexaggerate the efficacy and effectiveness of the new treatment.

Such exaggerations also appear in medical journals and other professionalvenues. Specialists have announced “the decade of thebrain,”3 a“new era of proactive rather than reactive stroketherapy,”4 and“transformation from a realm of fatalism to a field of therapeuticopportunities.”5Landis and associates write, “With the tools in hand, recognition ofischemic stroke as a medical emergency and application of prudent thrombolytictechniques will have a major impact on stroke morbidity andmorality.”6(p226)Some commentators even warn of lawsuits if thrombolytic agents are not givento eligible strokepatients.7 Theseclaims are without scientificbasis.8,9,10Yet, robust exaggerations and effusive sentiments of this sort appear notmerely in the literature concerning acute stroke but on other topics as well.They are a serious problem because they exhibit interpretation bias, which maylead to errors in clinical judgment and to unrealistic patientexpectations.11

SOURCES OF INTERPRETATION BIAS

Interpretation bias occurs when systematic distortions arise in theinterpretation of data from scientific studies. Ideally, interpretation biaswould be eliminated directly at the clinical level. Each physician would be anexpert at interpreting scientific data and would have unlimited time to reviewthe medical literature. Indeed, some progress has been made toward this idealwith the emergence of evidence-based medicine. Still, given the astoundingvolume of medical data and the complexities of statistical analysis, mostclinicians need help to integrate the available information into justifiableclinicalstrategies.12

Interpretation bias usually occurs at intermediary stages, as data sifttheir way through various medical and nonmedical interpreters on their way toclinicians and patients. At least two forces outside the medical professionpertain. First is the need for the news and entertainment industry to discoverinteresting and important events. Second is the imperative of drug and devicemanufacturers to sell their products.

In media coverage of health research, the tendency is to focus on dramaticurgent interventions and to highlight the most startling or momentous claimsabout possible medical benefits. Inaccurate or stilted reporting frequentlyfollows, often with powerful effects on patient and clinicianperceptions.13,14Media demands or pressure from political support groups may produce a feelingof urgency among medical researchers to announce something memorable andimportant.12

Drug and device manufacturers target individual clinicians and patientswith advertisements, gifts, andgrants.15 Althoughmany clinicians maintain that their practice patterns are unaffected bypropaganda from pharmaceutical corporations, the companies themselves clearlybelievedifferently.16Sponsorship plays an important role in cultivating: expectation bias,“bandwagon bias,” and protreatmentbias.12 Expectationbias can occur when companies aggressively hype their products before theproducts are actually tested. Subsequently, medical researchers andinterpreters may exhibit bias in finding what they expect to find. Bandwagonbias, which is closely related, occurs when companies enlist a critical massof support for their products. As McCormack and Greenhalgh note, an unstatedpresupposition seems to be that “if enough people say it, it becomestrue.”12Finally, drug and device manufacturers benefit from an implicit protreatmentbias. When few proven or well-publicized alternatives are available,clinicians and patients will use their products even when little or no dataexist that demonstrate clinical benefits.

The deleterious influence of corporate sponsorship has led to a review ofresearchers' financial conflicts ofinterest.17,18Medical journals and other reputable sources of clinical interpretation nowfrequently require authors' disclosure of possible financial conflicts ofinterest.19 Whethersuch measures are sufficient to counterbalance bias remains a topic fordebate. To eradicate corrupting influences, it may be tempting to severaltogether the relationship between medical inquiry and for-profit industry.However, such measures would threaten the vitality of clinical research byundermining resources.

FALLACY OF SELECTIVE EMPHASIS

Perhaps the focus on financial conflicts of interest has diverted attentionfrom another source of bias in clinical interpretation: the fallacy ofselective emphasis. This fallacy (originally described by philosopher JohnDewey) occurs when intense focus on a narrow topic of interest manifestsitself in an unintentional but systematic exaggeration of the importance ofthe particular point ofinterest.20(pp31-41)In epidemiologic parlance, we might equate this fallacy with“preoccupation” bias. When people spend much time and energyscrutinizing something, they often assume that the object of scrutiny must beimportant. Two important sources of the fallacy of selective emphasis seem toapply when medical researchers interpret their own work or related work intheir field.

First, most researchers are “superspecialists”—that is,medical specialists with particular research interests that occupy a largeproportion of their time and energy. Because of their narrow focus,superspecialists may be prone to develop partially skewed medical worldviews.But accurate interpretation requires someone who can estimate the effects ofnew ideas within a wide range of clinical scenarios and who is adroit atconsidering a gamut of competing possibilities. A competent generalist,specially qualified in interpretive methods and thoroughly familiar with thepertinent literature, seems best for this role.

Second, researchers have a natural interest in promoting their chosenspecialties and areas of research. This interest is not merely a matter ofmoney and greed but may involve the enhancement of prestige, professionalself-image, and the sense of a personal calling. Researchers would not choosetheir specialties if they did not think that they were interesting, promising,and important. These sources of optimism are a credit for the medicalresearcher but a liability for anyone with the task of interpreting themedical literature—especially for those involved in deciphering theeffects of their own work.

TOWARD EFFECTIVE CLINICAL INTERPRETATION

McCormack and Greenhalgh have suggested that journal editors“encourage authors to present their results initially with a minimum ofdiscussion so as to invite a range of comments and perspectives fromreaders.”12This is excellent advice but may fall short of an adequate remedy for thefallacy of selective emphasis (because most clinicians read the literatureselectively). If journal editors and regulators could turn to a cadre ofrelatively neutral, uninvested clinicians with special methodologic expertise,then perhaps the threat of preoccupation bias would be mitigated evenfurther.

To effect such a scenario, two strategies suggest themselves. First,medical centers and universities could distinguish between two types ofclinical role or faculty appointment: clinician-researcher andclinician-interpreter. Second, medical journals, medical societies, and/orgovernment regulators could assemble boards of expert clinician-interpretersto review scientific studies and make recommendations for practice or publicpolicy. Britain's National Institute for Clinical Excellence—whichprovides national guidance on individual technologies, the management ofspecific conditions, and clinical audit—might exemplify this sort ofproject, if it were to recruit effective clinician-interpreters to developguidelines and review the literature.

Clinician-researchers would continue with their current responsibilitiesand would be free (or even encouraged) to collaborate with private, for-profitindustry. Probably most clinician-researchers would continue to besuperspecialists. Clinician-interpreters, on the other hand, would becommitted to attitudes of economic impartiality, balanced skepticism, andmethodologic rigor. The best clinician-interpreters would be experiencedgeneralists skilled in evaluating study design and addressing questions ofexternal validity. (The external validity of a study is the degree to whichresults of the study apply in actual practice settings.) Faculty in internalmedicine, family practice, general pediatrics, and emergency medicine could beideally suited. To guarantee familiarity with a wide range of practicesettings, the recruitment of clinician-interpreters from rural regions orother settings outside the academy might also be desirable.

When government agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)seek expert advice, they could turn to such panels of clinician-interpreters.This policy would be a significant departure from current practice. When thePeripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee (of the FDA)considered the use of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) for acute stroke, itheard mostly from clinical investigators involved in the NINDS trial (the onlymajor trial in which tPA showed significant benefit over nontreatment). Mostof these investigators were also employed by Genentech (which markets tPA).The composition of the advisory committee was itself skewed, consistingentirely of neurologic specialists without a single emergency physician orother generalist (transcript of Advisory Committee meeting, June 6, 1996, opencommittee discussion on Product License Application 96-0350 for Activase[alteplase], Genentech, for management of acute stroke. Obtained from FDA,Bethesda, MD).

Interestingly, the FDA's advisory committee invited public participation,but only Karen Putney of the National Stroke Association spoke up. Hercomments nicely illustrate the threat of publicity bias and protreatmentbias:

[National Stroke Association] understands that finding a treatment foracute ischemic stroke for which there is yet no approved therapy will do morethan anything else to improve public awareness and understanding, compel themedical community to treat stroke emergently, and improve patient outcome.This study heralds a new approach to stroke and carries the hope oftransforming the hopelessness surrounding stoke into active, aggressive, andeffective intervention to salvage brain tissue, reduce disability, and savelives.

We see here the usual false dogmas about thrombolysis for stroke: first,that improving public awareness about stroke is so important that it should bea factor in determining whether the use of a dangerous drug such as tPA isapproved; second, that tPA saves lives; and finally, that the medicalcommunity is remiss if it does not incorporate the new technology quickly intoits standard of care. These are the sort of errors that clinician-interpreterswould be trained to avoid.

The FDA is not the only organization that would benefit from a panel ofclinician-interpreters. When the American Heart Association examined the useof thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke in October 1999, they recruited anemergency physician—Jerome R Hoffman—but then dropped his namefrom their list of panel members when he refused to sign the resultingrecommendations (with which hedisagreed).21Initially, Hoffman was asked to submit a rebuttal essay, but his submissionwas never published. Later, he asked if the American Heart Association wouldpublish a shorter one- to two-paragraph dissent alongside the recommendations.When this offer was refused, he requested that the following statement beappended to the document: “Jerome R Hoffman also participated in thepanel but disagrees with the recommendations contained in this paper.”This request was also denied.

CONCLUSION

The fallacy of selective emphasis is an important source of interpretationbias that might be ameliorated by distinguishing between professionalclinician-interpreters and clinician-researchers and by recruitinginterpreters who are generalists with expertise in methodology. This strategywould integrate nicely with efforts to reduce other sources of interpretationbias, because nonresearchers are less apt to have financial conflicts ofinterest and may be less prone to expectation bias.

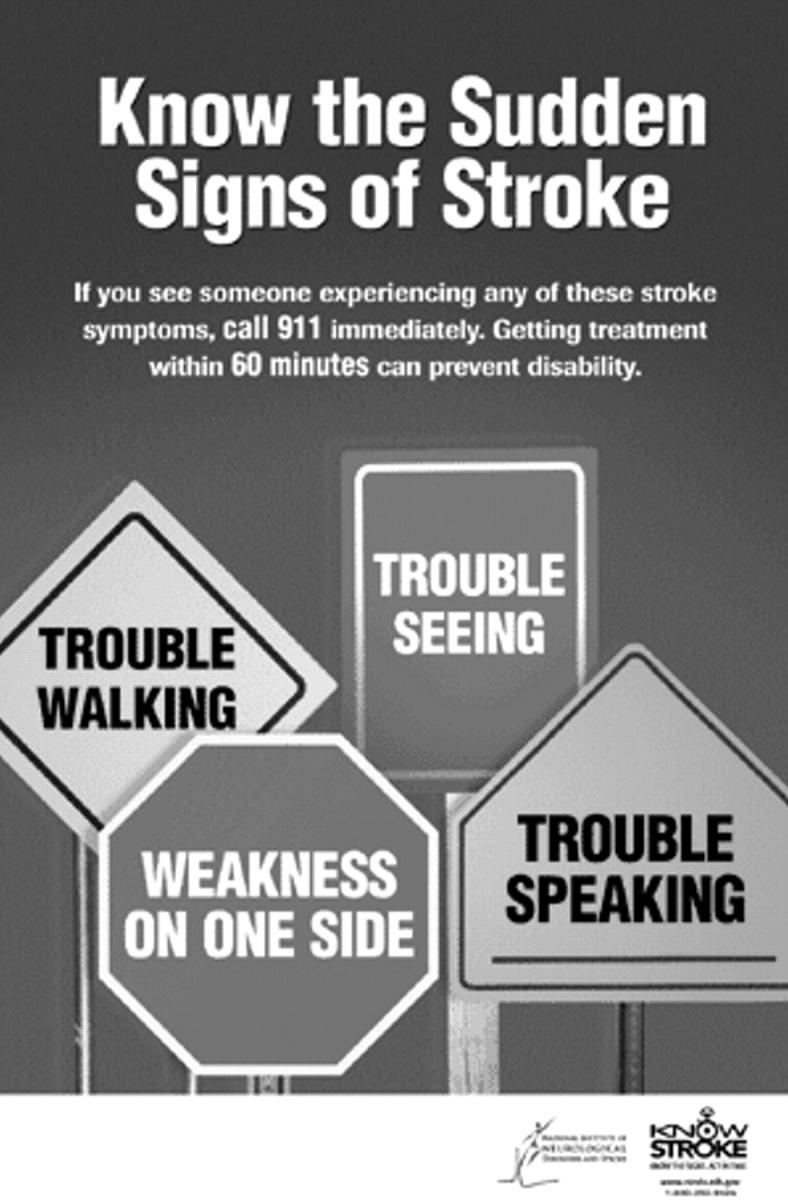

Figure 1.

Does this education campaign show protreatment bias?

Acknowledgments

Jerome Hoffman, Gavin Yamey, and an anonymous reviewer provided helpfulsuggestions pertaining to this essay.

Competing interests: None declared

- Interpretation bias occurs when there are systematic distortions in theinterpretation of data from scientific studies

- Interpretation bias may lead to errors in clinical judgment and tounrealistic patient expectations

- One source of interpretation bias is the “fallacy of selectiveemphasis,” which occurs when commentators focus intensely on a narrowpoint of interest and overemphasize its importance

- The establishment of a division of labor between clinician-researchers andclinician-interpreters might help to ameliorate the fallacy of selectiveemphasis

- Steps to address the fallacy of selective emphasis should be coordinatedwith other efforts to reduce interpretation bias

References

- 1.Schrof JM. Stroke busters: new treatments in the fight against“brain attacks.” US News World Rep 1999. March 15;126:62-64, 68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Kummer R, Allen KL, Holle R, et al. Acute stroke: usefulness ofearly CT findings before thrombolytic therapy.Radiology 1997;205:327-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camarata PJ, Heros RC, Latchaw RE. “Brainattack”—the rationale for treating stroke as a medical emergency.Neurosurgery 1994;34:144-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alberts MJ. Hyperacute stroke therapy with tissue plasminogenactivator. Am J Cardiol 1997;80:29D-34D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hachinski V. Thrombolysis in stroke: between the promise and theperil [editorial]. JAMA 1996;276:995-996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landis DMD, Tarr RW, Selman WR. Thrombolysis for acute ischemicstroke. Neurosurg Clin N Am 1997;8:219-226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wehrmacher WH, Iqbal O, Messmore H. Brain attack: who will writethe orders for thrombolytics? [letter]. Arch InternMed 2000;160:119-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heller RF, Langhorne P, James E. Improving stroke outcome: thebenefits of increasing availability of technology. Bull WorldHealth Organ 2000;78:1337-1343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Kammersgaard LP, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS.Predicted impact of intravenous thrombolysis on the prognosis of generalpopulation of stroke patients: simulation model. BMJ 1999;319:288-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman JR. Point-Counterpoint: Should physicians give tPA topatients with acute ischemic stroke? Against: And just what is the emperor ofstroke wearing? West J Med 2000;173:149-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SJ, Fairclough D, Antin JH, Weeks JC. Discrepancies betweenpatient and physician estimates for the success of stem cell transplantation.JAMA 2001;285:1034-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormack J, Greenhalgh T. Seeing what you want to see inrandomised controlled trials: versions and perversions of UKPDS data. UnitedKingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. BMJ 2000;320:1720-1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moynihan R, Bero L, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Coverage by the newsmedia of the benefits and risks of medications. N Engl JMed 2000;342:1645-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips DP, Kanter EJ, Bednarczyk B, Tastad PL. Importance of thelay press in the transmission of medical knowledge to the scientificcommunity. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1180-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilkes MS, Bell RA, Kravitz RL. Direct-to-consumer prescriptiondrug advertising: trends, impact, and implications. Health Aff(Millwood) 2000;19:110-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a giftever just a gift? JAMA 2000;283:373-380.10647801 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tenery RM. Interactions between physicians and the health caretechnology industry. JAMA 2000;283:391-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodenheimer T. Uneasy alliance—clinical investigators and thepharmaceutical industry. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1539-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krimsky S, Rothenberg LS. Conflict of interest policies in scienceand medical journals: editorial practices and author disclosures.Sci Eng Ethics 2001;7:205-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewey J. The Later Works, 1925-1953—Vol 1, 1925:Experience and Nature. Boydston JA, ed. Carbondale, IL: SouthernIllinois University Press; 1988.

- 21.Hoffman JR. Annals supplement on the American HeartAssociation proceedings [letter]. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]